Abstract

Background

Cancer during pregnancy is relatively rare but may lead to maternal mortality. We aimed to assess the incidence of cancer related maternal mortality and the neonatal outcome in these patients. Also, doctor- and patient-related delay in cancer diagnosis and therapy among patients with cancer related maternal mortality is assessed.

Methods

Maternal mortality was defined as death during pregnancy or within 1 year after delivery. Data of the Dutch Maternal Mortality Committee was used to calculate the cancer related maternal mortality rate and to assess neonatal outcome in the Netherlands. Delay was scored by ten medical specialist based on case descriptions.

Results

Cancer related maternal mortality rate was 1.23 per 100,000 live births. Delay in either diagnosis or treatment occurred in 65%. Delay in diagnosis was more frequent then delay in treatment, and was mainly caused by health care providers. Only 77% of pregnancies were ongoing, and 65% ended preterm of which 85% was induced.

Conclusions

Avoiding delay in diagnosis and therapy in case of pregnancy related cancer could potentially improve maternal and neonatal outcome. It is therefore essential to increase awareness among health care providers about the occurrence and recurrence of cancer in pregnancy and the possibilities of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in these women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In western countries, maternal mortality, defined as death occurring during pregnancy or within the first year after delivery, is a relatively small but still serious problem. Most women die of pregnancy related problems, but approximately 25% of the maternal deaths are non- pregnancy related. Pregnancies complicated by cancer are a potential threat for both maternal and fetal wellbeing. Incidence of cancer during pregnancy has been estimated to be one in 1000 pregnancies, but due to increasing maternal age and the increasing incidence of risk factors for cancer, e.g. obesity, this incidence is rising [1, 2]. Schutte et al. reported no cancer related maternal deaths between 1983 and 1992 and three between 1993 and 2005 [3].

If standard therapy is started without delay, prognosis of pregnant patients is comparable to non-pregnant patients when corrected for maternal age and stage. Cancer related symptoms can mimic those of physiological pregnancy changes [4]. They may be interpreted by both patient and health care providers as pregnancy related, delaying an accurate diagnosis [5, 6]. This delay can lead to a more advanced stage of disease, causing a higher mortality rate [7].

In the management of pregnant patients with cancer, the unborn child is an important second patient that needs to be taken care of. Treatment regimens must be carefully evaluated in order to ensure fetal safety. Recent studies have shown that several cancer treatments seem to be feasible during pregnancy without increasing the change of congenital malformations [8, 9]. Chemo- and radiotherapy during pregnancy does not seem to affect the neuropsychological development up to 3 years. Unfortunately, substandard and/or delayed treatment and iatrogenic preterm birth is still a major problem in this specific patient group [10]. In fact, preterm delivery is a high risk factor for developmental problems later in life [8].

In advanced stages of disease, treatment is often more extensive and maternal condition deteriorated. Minimizing delay in diagnosis will not prevent all maternal deaths, but the outcome for both mother and neonate is likely to be improved. However, literature on current cancer related maternal mortality is scarce. Therefore, in the present study the incidence of cancer related maternal mortality in the Netherlands will be calculated and the occurrence of doctor- and patient-related delay in diagnosis and therapy will be evaluated. Finally, the neonatal outcome of the children of the mothers that died of cancer during pregnancy will be analysed.

Methods

This study is a nationwide observational cohort study using the non-public database of the Dutch Maternal Mortality Committee (MMC) after written permission of the board of the committee. The methods of the MMC and definitions of maternal mortality used have been described previously [3]. Briefly, the MMC discusses reported cases, collects missing data and evaluates the avoidability of maternal mortality. Maternal mortality is defined as death occurring during pregnancy or within the first year after delivery. Their database is crosschecked with the Central Bureau of Statistics of the Netherlands (CBS). Missing cases are anonymously added to the database.

Selection criteria and data collection

Patients registered between 2001 and 2012 by the MMC who died during pregnancy or within 1 year postpartum were screened. We selected the patients that died because of (recurrent) cancer. Patients with cancer related symptoms during pregnancy but diagnosed after delivery were included. If patients died from cancer but only showed symptoms after delivery, they were not eligible. Missing data in the reports of the MMC were completed by review of the medical files. Ten medical specialists from different disciplines, including medical oncologists, gynaecological oncologists and obstetricians, were provided detailed case descriptions, with information on diagnosis and therapy. They scored anonymously whether delay had occurred and whether this was doctor- and/or patient-related delay. Delay was defined as an extension of the period between symptoms/presentation and diagnosis, and diagnosis and treatment, compared to optimal care based on expert opinions. For the patients with recurrent disease during pregnancy, delay was assessed from the moment of the new onset of symptoms caused by recurrent disease. Delay due to other primary health care providers like midwifes were considered to be doctor-related delay.

Statistical analysis

Because of the observational nature of this study, statistical analysis was restricted to descriptive statistics and the evaluation of inter-observer agreement with a kappa score. Because our data was scored by a fixed number of observers using a numeric scorings system the Fleiss kappa score was used.

Results

Incidence and maternal mortality rate

Between 2001 and 2012, 32 cancer related maternal deaths were reported to the MMC. Four of these cases were excluded: two patients were treated with chemotherapeutic agents for other indications than malignant disease, one patient had a benign brain tumour and one patient became symptomatic after delivery. Two additional anonymous cases were reported by the CBS, which were included but could only be used to calculate the incidence of cancer related maternal mortality. The 26 remaining cases were available for analysis of delay. With an average number of 188,604 live births per year (range 202,603 in 2001 to 175,959 in 2012) in the Netherlands, the Dutch cancer related MMR between 2001 and 2012 was 1.23 per 100,000 live births [11].

Patient characteristics

Brain tumours, gastro-intestinal tumours and melanomas were the most common types of cancer causing maternal mortality. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median maternal age at diagnosis was 34 years (range 27–45 years). Of the 26 patients, 73% was diagnosed during pregnancy; one patient (4%) was diagnosed in the first trimester, ten patients (39%) in the second trimester and eight patients (31%) in the third trimester. Seven patients (27%) were diagnosed after delivery, but experienced cancer related symptoms during pregnancy. Median survival after diagnosis was 101 days with a range of 3–352 days. Stage IV disease was present at diagnosis in 90% of the patients; the other 10% had stage III disease. Four patients had recurrent disease during pregnancy and were diagnosed with advanced stage disease at recurrence while pregnant; one melanoma and three astrocytomas.

Standard curative therapy was applied in nine cases. Four patients received adjusted treatment because of pregnancy or complications. In six cases, the patient decided to postpone treatment until a higher gestational age (GA). Four of these patients were still induced preterm. Palliative care was the only option for six patients. For one patient, data on therapeutic decision-making was not available.

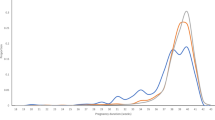

Obstetrical outcome

Obstetrical outcome was available for all 26 patients with detailed case information (Fig. 1). Five pregnancies were complicated by intra-uterine fetal death: 1) at a GA of 17 weeks, when mother died of an astrocytoma, 2) at a GA of 18 weeks, when mother died of a glioblastoma multiforme, 3) at a GA of 22 weeks after suboptimal intubation during surgery, 4) at a GA of 27 weeks, when mother was admitted with a status epilepticus due to progressive glioblastoma multiforme, and 5) at a GA of 29 weeks, when the mother died suddenly at home due to metastatic melanoma. One patient experienced an immature delivery at a GA of 18 weeks after a bilateral laparotomic oophorectomy.

Of the 20 ongoing pregnancies ending in a live birth, one was a twin pregnancy resulting in 21 live new-borns. However, one of the children died 4 days after caesarean section at a GA of 26 weeks due to complications of extreme preterm delivery. Caesarean section was performed because of presumed HELLP syndrome. After delivery, the complaints progressed and stage IV cancer of unknown origin with liver metastases was diagnosed.

Median GA at delivery of all 20 ongoing pregnancies was 35 weeks (range 26–40 weeks). Thirteen (65%) of these ended preterm, of which 11 deliveries (85%) were vaginally induced (n = 3) or terminated by caesarean section (n = 8). Reasons for iatrogenic preterm delivery were maternal deterioration (n = 4), therapy planning (n = 4) or obstetrical complications (n = 3).

Doctor-related and patient-related delay

Ten medical specialists dealing with pregnant cancer patients from six different medical centres independently scored all 26 case descriptions on delay in diagnosis and treatment. The score was considered conclusive if six or more specialists shared the same opinion.

See Table 2 for an overview of the types of delay. In 65% of patients (n = 17) delay was found to be present, 50% (n = 13) or all patients were found to have delay in diagnosis and 27% (n = 7) in starting therapy. Three patients were considered to have both types of delay. Regarding the other nine cases, six showed no signs of delay, two had not enough information available for adequate evaluation and one score was inconclusive. Even in patients with recurrent disease, delay in diagnosis occurred in 50%. In one of these patients with recurrent astrocytoma, delay was caused by doctors in a non-academic centre where symptoms like increasing blood pressure, headache and general seizure were interpreted as eclampsia, for which delivery was induced. In the other patients with delay in diagnosis with recurrent melanoma, progressive back pain and pain on her ribcage at a GA of 35 weeks, was treated with pain medication until 2 weeks after delivery. Diagnostic investigations showed wide spread melanoma metastasis including bones and lungs.

Inter-observer agreement on the presence of delay in diagnosis was found to be substantial, with a Fleiss Kappa score of 0.71. The agreement for the delay in therapy was less, with a score of 0.33, which is a fair agreement.

In the cases where delay in diagnosis was caused, the origin was evaluated to assess whether the delay was caused by the involved health care provider or by the patient. In eight of 13 patients with delay in diagnosis, doctor-related delay was considered to have influenced the time between presentation of symptoms and diagnosis. In two additional cases, both the health care provider and the patient caused delay. For the ten patients with doctor-related delay, delay was caused by the midwife (n = 5), general practitioner (n = 2) and by doctors from a non-academic centres (n = 2) and in two patients, multiple non-academic health care workers caused delay. In nine cases, symptoms were described as pregnancy related complaints, and in one patient, a wrong diagnosis was made based on additional diagnostic tests. In one patient, delay was caused by a long period between referral to a hospital and actual diagnostic evaluation. Patient-related delay in diagnosis was present in only two cases, and in one case enough information was not available to evaluate the cause of delay.

Doctor-related delay in therapy was found in four of the seven cases. In the other three cases, patients refused the advised treatment during pregnancy and wished to delay until after delivery.

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the second study to evaluate specific cancer related MMR and the first to report on delay in either diagnosis or treatment and obstetrical outcome in this specific population. The cancer related MMR in the Netherlands between 2001 and 2012 was 1.23 per 100,000 live births, with the highest incidence of cause related death due to brain tumours, gastro-intestinal tumours and melanomas. Delay in diagnosis was more frequent than delayed treatment, and was mainly caused by health care providers. Of the 77% ongoing pregnancies, 65% delivered preterm, often after induction of labour for oncological reasons. One neonatal death occurred.

The only other article published on cancer related maternal mortality, in 1990 by Sachs et al. [12], reported on their population-based study in the USA between 1954 and 1985 and found a cancer related MMR of 1.44. They defined maternal mortality as death during pregnancy or within 90 days after delivery. Because this is different from the current WHO definition used in our study, comparing these results to this present study is not feasible [12].

The outcome for pregnant patients with cancer is not different from non-pregnant patients when corrected for stage and age at diagnosis [7]. Previous literature has reported that patients with cancer during pregnancy present with a more advanced stage of disease due to delay in diagnosis [5, 6]. Since stage of disease at diagnosis is strongly correlated to prognosis, this delay may contribute to a worse maternal outcome and should be avoided where possible. For some tumours, the effect of delay on the prognosis is less, since lower stage of disease still has a poor prognosis. However, even in these cases, prognosis is better when diagnosed in an earlier stage.

Delay in therapy until after delivery may postpone adequate therapy for the mother, thereby contributing to a worse maternal prognosis. If preterm induction of labour is aimed for to start therapy postpartum, the prognosis of the unborn child is influenced as well. A recent study [8] showed that there was no difference between neuropsychological development between children exposed to chemotherapy in utero and healthy controls. In fact, preterm birth had a bigger impact on neuropsychological outcome in both groups with an increase of 2.6 IQ points per week gestation at birth [8]. In our study population, delay in diagnosis may have contributed to a more advanced stage of disease requiring systemic therapy in order to improve survival. In 27% of the cases, therapy was delayed until spontaneous delivery or until a certain GA was reached and pregnancy could be terminated. Raising awareness on cancer in pregnancy and the possibilities in diagnostic and therapeutic treatment modalities among health care providers may help in reducing the morbidity and mortality of these patients and their children.

One of the main limitations of our study include that reporting fatalities to the Dutch MMC is on a voluntary basis. Even though the committee is well known among gynaecologists, it is possible that a year after pregnancy, the relation between death and pregnancy by other medical professionals may be overlooked. Cross checking with the CBS database revealed only two more cases, but the actual number of cancer related (late) mortalities might be higher than reported. Furthermore, there are some difficulties in studying delay, as the extent of delay for one tumour will not have the same consequences as delay for another, more aggressive, tumour and if curative therapeutic options are not available, delay will not change the fatal outcome. However, the various medical specialists reached an overall agreement on the occurrence of delay, which makes our findings more reproducible. Our study population is small, because of the low incidence of cancer related maternal mortality.

We cannot exclude that treatment in a multidisciplinary team may influenced outcome. Practitioners with experience in oncologic treatment in pregnancy will probably hesitate less to start treatment, but they are often dependent on referral from first-line healthcare workers and they cannot change the stage of cancer. This emphasizes that awareness in all practitioners is essential.

Conclusions

In conclusion, cancer related maternal mortality is rare but contributes to high neonatal morbidity and mortality rates, mainly due to iatrogenic preterm delivery. Delay in diagnosis and treatment occurs frequently in this group and is mainly caused by health care providers. This can only be resolved by increased awareness among health-care professionals.

Abbreviations

- CBS:

-

Central Bureau of Statistics

- GA:

-

Gestational age

- MMC:

-

Maternal Mortality Committee

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality rate

References

Lee YY, Roberts CL, Dobbins T, Stavrou E, Black K, Morris J, et al. Incidence and outcomes of pregnancy-associated cancer in Australia, 1994–2008: a population-based linkage study. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119:1572–82.

Parazzini F, Franchi M, Tavani A, Negri E, Peccatori FA. Frequency of pregnancy related cancer: a population based linkage study in Lombardy, Italy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27:613–9.

Schutte JM, Steegers EAP, Schuitemaker NWE, Santema JG, de Boer K, Pel M, et al. Rise in maternal mortality in the Netherlands. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;117:399–406.

de Haan J, Vandecaveye V, Han SN, Van de Vijver KK, Amant F. Difficulties with diagnosis of malignancies in pregnancy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016;33:19–32.

Andersson TM, Johansson ALV, Fredriksson I, Lambe M. Cancer during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a population-based study. Cancer. 2015;121:2072–7.

Voulgaris E, Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Cancer and pregnancy: a comprehensive review. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:e175–85.

Stensheim H, Møller B, Van Dijk T, Fosså SD. Cause-specific survival for women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy or lactation: a registry-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:45–51.

Amant F, Vandenbroucke T, Verheecke M, Fumagalli M, Halaska MJ, Boere I, et al. Pediatric outcome after maternal cancer diagnosed during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1824–34.

Amant F, Han SN, Gziri MM, Vandenbroucke T, Verheecke M, Van Calsteren K. Management of cancer in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:741–53.

Han SN, Kesic VI, Van Calsteren K, Petkovic S, Amant F. Cancer in pregnancy: a survey of current clinical practice. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;167:18–23.

Central Bureau of Statistics of the Netherlands. Geboorte naar diverse kenmerkingen. [cited 2015 Nov 1]. Available from: http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLNL&PA=37422ned&D1=0,4-5,7,9,11,13,17,26,35,40-41&D2=0,10,20,30,40,(l-4)-l&HD=090218-0953&HDR=G1&STB=T.

Sachs BP, Penzias AS, Brown DA, Driscoll SG, Jewett JF. Cancer-related maternal mortality in Massachusetts, 1954–1985. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;36:395–400.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the medical specialists and outpatient department managers who helped collecting all data necessary for completing the database and scoring the case reports. No funding was received.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this project.

Availability of data and materials

The Dutch Maternal Mortality Committee is a non-public database and access to this database for this manuscript was granted by the secretary of the committee after deliberating with the board members. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the Dutch Maternal Mortality Committee, care of Doctor Joke Schutte: j.m.schutte@isala.nl, on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH contributed to the article with the design of the protocol, planning of the project, data collection, analysis of hospital files, interpretation of data, statistical analysis and writing the article. CL contributed to the article with the design of the protocol, support in planning the project, supervising data collection, analysis and interpretation of collected data, and critical revision of the article. JS contributed to the article with the data collection of maternal deaths during many years as member of the MMC, scoring of all cases and revision of the article. LZ contributed to the article with the scoring of all cases and revision of the article. CG contributed to the article with the design of the protocol, supervision of planning the project and of analysis of data and final revision of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Medical ‘Ethical Research Committee’ of the VU University Medical Centre granted an exemption from requiring ethical approval for this research project.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Haan, J., Lok, C.A.R., Schutte, J.S. et al. Cancer related maternal mortality and delay in diagnosis and treatment: a case series on 26 cases. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1639-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1639-3