Abstract

Background

Breast milk is known to contain many bioactive hormones and peptides, which can influence infant growth and development. In this context, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the influence of different clinical pregnancy conditions on hormone concentrations in colostrum and mature breast milk.

Methods

An observational study was performed with mother-newborn pairs divided into five groups according to maternal clinical background: diabetes (12), hypertension (5), smoking (19), intrauterine growth restriction of unknown causes with small-for-gestational-age newborns at delivery (12), and controls (21). Socioeconomic data, anthropometric measurements and breast milk samples were collected between the first 24 and 48 h and 30 days postpartum. Leptin, adiponectin, and insulin levels in breast milk were measured by immunoassays.

Results

A significant decrease in leptin (p = 0.050) and insulin (p = 0.012) levels from colostrum to mature breast milk in mothers of small-for-gestational-age infants was observed. Maternal body mass index was correlated with both leptin and insulin, but not with adiponectin. Insulin levels were negatively correlated to infant weight gain from birth to one month (p = 0.050). In addition, catch-up growth was verified for small-for-gestational-age infants throughout the first month of life.

Conclusions

This study suggests that a remarkable decrease in leptin and insulin levels in mature milk of mothers of small-for-gestational-age newborns may be involved in the rapid weight gain of these newborns. The physiological and external mechanisms by which these significant decreases and rapid weight gains occur in this group remain to be elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast milk contains bioactive components, which play an important biological role for the newborn. Leptin, insulin and adiponectin are some of the hormones that possess important functions in energy balance regulation, food intake, and child body composition [1,2,3]. Leptin is an anorexigenic hormone that acts on neuronal cells of the hypothalamus [4]. It is produced by adipocytes, the human placenta and mammary glands [5,6,7]. Insulin displays anorexigenic effects similar to leptin [8]. It captures glucose for several tissues after food intake [9], and seems to interfere on enteral hormones slowing gastric emptying and promoting a sensation of satiety [10]. Adiponectin is secreted by adipose tissue and stimulates food intake and decreases energy expenditure, the inverse action of leptin and insulin [11, 12]. This hormone acts on glucose and lipid metabolisms, improving insulin sensitization and fatty acid oxidation, while also inhibiting hepatic glucose production [13, 14].

It is known that breast milk composition can be influenced by the maternal clinical background [11, 12], in which the body fat deposits are proportionally associated to leptin, adiponectin and insulin levels. Positive correlations have been demonstrated between maternal body mass index (BMI) and hormone concentrations in breast milk [12, 15,16,17,18,19,20], and between maternal BMI and serum leptin concentrations in breastfed infants [21].

Insulin quantification in the breast milk of diabetic mothers has been described by Whitmore et al. [22], who observed no differences in insulin levels over 24 h or in relation to diabetes type. Breast milk components can be modified by smoking, which induces variations in the concentration of certain cytokines [23,24,25]. However, no such changes have been observed for leptin or other hormones [24, 26]. Liu et al., assessed adiponectin concentrations in the breast milk of mothers presenting preeclampsia and observed increases when compared to controls [27].

In this context, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the influence of different clinical conditions during pregnancy (diabetes, hypertension, smoking and idiopathic intrauterine growth restriction) on hormone concentrations in colostrum and mature breast milk and their associations with the early development of the newborns.

Methods

The present prospective and observational study was part of a larger project, named Impact of Perinatal Different Intrauterine Environments on Child Growth and Development in the First Six Months of Life (IVAPSA Birth Cohort Study). The research protocol has been previously published [28]. The recruitment for the IVAPSA study was carried out in public hospitals - the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre and the Grupo Hospitalar Conceição (Hospital Fêmina and Hospital Conceição). Both are similar in maternal and child care and are located in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Mothers were recruited at 24 to 48 h postpartum and were divided into five groups according to maternal clinical background and pregnancy outcome: (I) gestational diabetes treated only by diet (GDM) (II) gestational hypertension without intrauterine growth restriction (HTN). These maternal clinical backgrounds (diabetes and hypertension) were previously diagnosed by prenatal physicians; (III) smoking (SMS) – mothers who smoked at any time during the pregnancy. Smoking mothers were selected by asking whether they had smoked during their pregnancy (1 cigarette or more); (IV) idiopathic intrauterine growth restriction with small-for-gestational-age (SGA) newborn at delivery – birth weight below 5th percentile [29]; and (V) control (CTL) – healthy mothers without diabetes or hypertension, who did not smoke during their pregnancy and who did not deliver an SGA baby for unknown causes. Exclusion criteria for all groups were HIV-positive mother status, preterm delivery (< 37 gestational weeks), newborn twin, newborn presenting malformations at birth or newborn requiring any hospitalization after delivery.

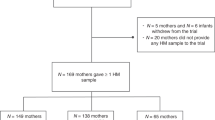

Two observations were performed, the first one between 24 to 48 h after delivery (PP) at the hospital, and the second at one month postpartum (1 M). Two-hundred and fourteen mother-newborn pairs were recruited (GDM – 25; HTN – 23; SMS – 58; SGA – 25; CTL – 83). The samples comprised mothers whose colostrum and mature breast milk were available. Many of the elected mothers did not provide breast milk, either during the postpartum period, at 1-month postpartum, or at any timeframe at all. In some cases, the sample amount was insufficient for all the conducted analyses. Information on birth, prenatal, social, economic, family, and health data were obtained during interviews, using a structured questionnaire developed by the investigators. Anthropometric measurements were also obtained: height and weight were measured using a portable stadiometer (AlturaExata®) and balance (Marte®), respectively. Infant weight gain was expressed from Z-scores for age according to the World Health Organization growth curves [30].

Breast milk (1–5 mL) was collected according to the availability of each mother in the first 24 and 48 h after delivery and 30 days postpartum. No control if mothers had breastfed their infants recently was performed, precluding the determination of whether the collected sample was hindmilk or foremilk. Previously published results have shown no significant difference in leptin [1, 22, 31,32,33] and insulin [22] levels between breast milk samples obtained from the initial and terminal phases of suckling. Maternal fasting status was also not controlled. After milk expression into sterile flasks by manual milking, the samples were immediately fractionated into labeled 1.5-mL tubes and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Prior to the assays, the milk samples (colostrum and mature milk) were thawed and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min to isolate fat in order to avoid its interference on the performed measurements. The isolated fat was discarded. No protease inhibitor was added.

Leptin, adiponectin and insulin were quantified in duplicate using commercially available Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) kits (Millipore®) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software– version 18.0 (SPSS Inc.). The descriptive analyses were performed according to the parametric or nonparametric distribution of data, as identified by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The chi-square test was used to verify sample homogeneity between groups, as was the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous data. The Wilcoxon test was used for paired nonparametric data (to evaluate differences in breast milk hormone concentrations from colostrum to mature milk), and the differences between groups were assessed by the medians of the Kruskal-Wallis test applying the Games–Howell post-hoc test. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) test applying Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to compare the parametric variables of maternal BMI between groups. Spearman coefficients were used to assess potential nonparametric correlations between breast milk hormone levels and maternal BMI. A significance level of 5% (p ≤ 0.05) and 95% confidence intervals were considered.

Results

Sixty-nine mother–child pairs were distributed across the five groups (12 GDM, 5 HTN, 19 SMS, 12 SGA, and 21 CTL). Of the mothers who provided breast milk in the first moment (colostrum), 9 (3 DM, 2 HTN, 1 SGA and 3 CTL) did not provide the second sample (mature milk). There were no significant differences in socioeconomic variables, as displayed in Table 1. Mothers of SGA newborns presented lower BMI values in all measurements.

All infants were still being breastfed during the second milk sampling of which forty-one were exclusively breastfeeding. Nineteen mothers offered other foods (solid, semi-solid or liquids) beyond breast milk and no differences in concurrent neonatal feeds and hormone concentration were observed (data not shown).

A significant difference between adiponectin concentrations of the HTN and CTL groups for colostrum (p = 0.015) was observed. Leptin and insulin concentrations decreased in all groups over time. These decreases were significant in mothers with SGA infants (p = 0.050), leading to the lowest leptin values of all groups at one month (p = 0.031) (Table 2).

Leptin concentrations in colostrum and mature breast milk were correlated with pre-gestational maternal BMI, as well as at delivery and at one month post-natal, whereas insulin presented a similar correlation for mature milk samples. Adiponectin showed no correlation with maternal BMI during any of the evaluated time-frames (Table 3).

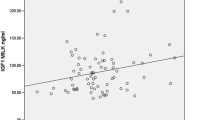

Insulin in mature milk was negatively correlated to infant weight gain at one month (p = 0.050) (Table 4). A catch-up growth was observed in the SGA group at one month, as displayed in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The evaluation of socioeconomic and maternal factors such as race, marital status, age, education level and social class showed a homogeneous sample, with similar characteristics despite the influence of different maternal gestational clinical conditions. Mothers of SGA infants presumably contributed through their lower BMI to restriction mechanisms of their offspring, although other factors may be involved, such as caloric restrictions or no apparent pathological conditions [34,35,36].

Results indicate no differences in insulin and leptin concentrations in colostrum regardless of the influence of the maternal gestational clinical condition, as previously demonstrated for diabetic [22] and smoking mothers [23, 26]. On the other hand, increased adiponectin levels have been observed for hypertensive mothers in comparison to controls, as described by Liu et al. [27]. Higher adiponectin serum and leptin levels in preeclampsia mothers have also been described by other authors [37, 38].

Decreases in hormone levels were observed during the first month of breastfeeding, in accordance to other studies [12, 17, 39,40,41]. Interestingly, breast milk from mothers of SGA infants exhibited a remarkable decrease in leptin and insulin levels at one month compared to other groups. Leptin and insulin breast milk levels correlate with their serum counterparts, which are proportional to maternal fat tissue [16, 19, 42]. Thus, these significant decreases can be related, at least in part, to the lower BMI of SGA mothers. A recent study demonstrated that the frequency and duration of breastfeeding presented a positive correlation with protein concentrations in breastmilk [43]. However, some authors have demonstrated that leptin levels are not modified comparing before and after suckling [1, 22, 31,32,33].

Maternal leptin and insulin serum concentrations during pregnancy increase concomitantly with maternal BMI [16, 44, 45], whereas adiponectin levels decrease [46]. Several studies have demonstrated a correlation between maternal BMI and satiety hormones in breast milk and serum of both mothers and neonates at delivery, as well as a broad variation in hormone levels [16,17,18,19,20,21, 42]. Herein, leptin concentrations in colostrum and mature milk positively correlated to maternal BMI before pregnancy, at delivery and at one month postpartum. Studies have demonstrated the same correlation for both colostrum [14, 17] and mature milk [6, 15, 17, 19, 47] with pre-gestational BMI, as well as maternal BMI at delivery [14] and at one month postpartum [1].

Maternal obesity has been associated with several adverse effects in children, such as metabolic, neurological and cardiovascular disorders later in life [48,49,50,51]. Increased leptin levels delivered to the fetus during pregnancy and breastfeeding may lead to predisposition for leptin resistance, impairing the ability of leptin to regulate appetite [52,53,54,55]. On the other hand, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) may also lead to leptin resistance [55,56,57,58]. Wattez et al. [59] have demonstrated leptin/insulin resistance in offspring from both undernourished dams and dams fed an obesogenic diet. The timing of neonatal leptin increases influenced by fetal nutrition contributes to the development of obesity in later life [58]. This reinforces the importance of maternal weight control before and during pregnancy in order to avoid adverse outcomes to the newborn.

Insulin levels in mature milk were also positively correlated to maternal BMI at each measurement period. However, no correlation was verified for colostrum samples. Few studies linking insulin concentrations in breast milk with maternal BMI are available. Ley and collaborators reported similar findings regarding pre-gestational BMI [12], while other researchers found no correlation between insulin levels and maternal BMI [15, 60]. In the present study, no correlation was observed between adiponectin concentrations and maternal BMI in any of the evaluated timeframes, in accordance to the literature [6, 7, 12, 41, 47, 61].

Insulin levels were negatively correlated with infant weight gain at one month of age, in accordance to its role as an energy balance, food intake and body composition regulator. In addition, high exposure to insulin during the lactation period has been associated with lower infant weight and lower lean mass at one month [15]. Insulin signaling pathways are involved in the development of the infant gastrointestinal system [10] and could act in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, affecting satiety and appetite control [8, 9]. Thus, it may influence postnatal growth.

The present study also demonstrates a catch-up growth of SGA infants through one month, which was not been observed for any other group. Rapid weight gain in both infancy and early childhood is a risk factor for adult adiposity and obesity [62]. In addition, rapid infant weight gain has also been associated with increased risk of being overweight at 4 years of age, independently of the potential confounders [62] and other unfavorable outcomes [56, 63,64,65,66]. Although early catch-up growth appears to be beneficial for the child, the Latin American SGA Consensus Guidelines recommend that children born SGA should not be allowed to gain weight too rapidly or excessively, probably in an effort to circumvent the development of metabolic disturbances [67].

The strengths of this study are the completeness of the collected maternal and neonatal data and the comparison of the impact of different maternal gestational clinical conditions on hormone concentrations in breast milk in a homogeneous sample. Some limitations are noteworthy, such as the lack of time control for the breast milk sampling or maternal fasting status, despite the fact that some studies have found no influence of these factors on hormone measurements [1, 22, 31,32,33]. Furthermore, the rigorous methodology for inclusion in the sample groups restricted the sample size.

Conclusions

The results obtained herein demonstrate different patterns of hormone concentrations in breast milk from mothers of SGA newborns. The significant decreases in leptin and insulin concentrations after birth may be involved in weight regain as usual in SGA newborns. Interestingly, these changes occurred after birth, suggesting that post-natal and even external mediating factors could contribute to this outcome. Further investigations are required to clarify these findings.

Abbreviations

- 1 M:

-

1 month postpartum

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CTL:

-

Control

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay

- GDM:

-

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

- HTN:

-

Gestational Hypertension

- PP:

-

Postpartum

- SGA:

-

Small-for-gestational-age

- SMS:

-

Smoking

References

Schueler J, Alexander B, Hart AM, Austin K, Larson-Meyer DE. Presence and dynamics of leptin, GLP-1, and PYY in human breast milk at early postpartum. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:1451–8.

Gupta M, Zaheer, Jora R, Kaul V, Gupta R. Breast feeding and insulin levels in low birth weight neonates: a randomized study. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:509–13.

Schuster S, Hechler C, Gebauer C, Kiess W, Kratzsch J. Leptin in maternal serum and breast milk: association with infants’ body weight gain in a longitudinal study over 6 months of lactation. Pediatr Res. 2011;70:633–7.

Savino F, Benetti S, Liguori SA, Sorrenti M, Cordero Di Montezemolo L. Advances on human milk hormones and protection against obesity. Cell Mol Biol. 2013;59:89–98.

Jaquet D, Leger J, Levy-Marchal C, Oury JF, Czernichow P. Ontogeny of leptin in human fetuses and newborns: effect of intrauterine growth retardation on serum leptin concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1243–6.

Weyermann M, Beermann C, Brenner H, Rothenbacher D. Adiponectin and leptin in maternal serum, cord blood, and breast milk. Clin Chem. 2006;52:2095–102.

Dundar NO, Dundar B, Cesur G, Yilmaz N, Sutcu R, Ozguner F. Ghrelin and adiponectin levels in colostrum, cord blood and maternal serum. Pediatr Int. 2010;52:622–5.

Pliquett RU, Führer D, Falk S, et al. The effects of insulin on the central nervous system-focus on appetite regulation. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38:442–6.

de Graaf C, Blom WA, Smeets PA, Stafleu A, Hendriks HF. Biomarkers of satiation and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:946–61.

Shehadeh N, Sukhotnik I, Shamir R. Gastrointestinal tract as a target organ for orally administered insulin. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:276–81.

Ley SH, O'Connor DL, Retnakaran R, Hamilton JK, Sermer M, Zinman B, Hanley AJ. Impact of maternal metabolic abnormalities in pregnancy on human milk and subsequent infant metabolic development: methodology and design. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:590.

Ley SH, Hanley AJ, Sermer M, Zinman B, O'Connor DL. Associations of prenatal metabolic abnormalities with insulin and adiponectin concentrations in human milk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:867–74.

Newburg DS, Woo JG, Morrow AL. Characteristics and potential functions of human milk adiponectin. J Pediatr. 2010;156:S41–6.

Bronsky J, Karpisek M, Bronska E, Pechova M, Jancikova B, Kotolova H, Stejskal D, Prusa R, Nevoral J. Adiponectin, adipocyte fatty acid binding protein, and epidermal fatty acid binding protein: proteins newly identified in human breast milk. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1763–70.

Fields DA, Demerath EW. Relationship of insulin, glucose, leptin, IL-6 and TNF-alpha in human breast milk with infant growth and body composition. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7:304–12.

Butte NF, Hopkinson JM, Nicolson MA. Leptin in human reproduction: serum leptin levels in pregnant and lactating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:585–9.

Eilers E, Ziska T, Harder T, Plagemann A, Obladen M, Loui A. Leptin determination in colostrum and early human milk from mothers of preterm and term infants. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:415–9.

Maple-Brown L, Ye C, Hanley AJ, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Maternal pregravid weight is the primary determinant of serum leptin and its metabolic associations in pregnancy, irrespective of gestational glucose tolerance status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4148–55.

Miralles O, Sanchez J, Palou A, Pico C. A physiological role of breast milk leptin in body weight control in developing infants. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1371–7.

Andreas NJ, Hyde MJ, Gale C, Parkinson JR, Jeffries S, Holmes E, Modi N. Effect of maternal body mass index on hormones in breast milk: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115043.

Savino F, Liguori SA, Oggero R, Silvestro L, Miniero R. Maternal BMI and serum leptin concentration of infants in the first year of life. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:414–8.

Whitmore TJ, Trengove NJ, Graham DF, Hartmann PE. Analysis of insulin in human breast milk in mothers with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:296368.

Zanardo V, Nicolussi S, Cavallin S, Trevisanuto D, Barbato A, Faggian D, Favaro F, Plebani M. Effect of maternal smoking on breast milk interleukin-1alpha, beta-endorphin, and leptin concentrations and leptin concentrations. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1410–3.

Etem Piskin I, Nur Karavar H, Arasli M, Ermis B. Effect of maternal smoking on colostrum and breast milk cytokines. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2012;23:187–90.

Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz A, Wos E, Aleksandrowicz E, Luczak G, Zagierski M, Martysiak-Zurowska D, Marek K, Kaminska B. Cytokine profile of mature milk from smoking and nonsmoking mothers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:382–4.

Ozkan B, Ermis B, Tastekin A, Doneray H, Yildirim A, Ors R. Effect of smoking on neonatal and maternal serum and breast milk leptin levels. Endocr Res. 2005;31:177–83.

Liu Y, Zhu L, Pan Y, Sun L, Chen D, Li X. Adiponectin levels in circulation and breast milk and mRNA expression in adipose tissue of preeclampsia women. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2012;31:40–9.

Bernardi JR, Ferreira CF, Nunes M, da Silva CH, Bosa VL, Silveira PP, Goldani MZ. Impact of Perinatal different intrauterine environments on child growth and development in the first six months of life-IVAPSA birth cohort: rationale, design, and methods. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:25.

Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan MA. United States National Reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):163–8.

World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: methods and development: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

Cannon AM, Kakulas F, Hepworth AR, Lai CT, Hartmann PE, Geddes DT. The effects of Leptin on breastfeeding behaviour. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:12340–55.

Karatas Z, Durmus Aydogdu S, Dinleyici EC, Colak O, Dogruel N. Breastmilk ghrelin, leptin, and fat levels changing foremilk to hindmilk: is that important for self-control of feeding? Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:1273–80.

Uçar B, Kirel B, Bor O, Kilic FS, Dogruel N, Aydogdu SD, Tekin N. Breast milk leptin concentrations in initial and terminal milk samples: relationships to maternal and infant plasma leptin concentrations, adiposity, serum glucose, insulin, lipid and lipoprotein levels. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:149–56.

Vahdaninia M, Tavafian SS, Montazeri A. Correlates of low birth weight in term pregnancies: a retrospective study from Iran. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:12.

Heaman M, Kingston D, Chalmers B, Sauve R, Lee L, Young D. Risk factors for preterm birth and small-for-gestational-age births among Canadian women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:54–61.

Xaverius PK, Salas J, Woolfolk CL, Leung F, Yuan J, Chang JJ. Predictors of size for gestational age in St. Louis City and county. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:515827.

Salimi S, Farajian-Mashhadi F, Naghavi A, Mokhtari M, Shahrakipour M, Saravani M, Yaghmaei M. Different profile of serum leptin between early onset and late onset preeclampsia. Dis Markers. 2014;2014:628476.

Haugen F, Ranheim T, Harsem NK, Lips E, Staff AC, Drevon CA. Increased plasma levels of adipokines in preeclampsia: relationship to placenta and adipose tissue gene expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E326–33.

Ilcol YO, Hizli ZB, Ozkan T. Leptin concentration in breast milk and its relationship to duration of lactation and hormonal status. Int Breastfeed J. 2006;1:21.

Martin LJ, Woo JG, Geraghty SR, Altaye M, Davidson BS, Banach W, Dolan LM, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Morrow AL. Adiponectin is present in human milk and is associated with maternal factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1106–11.

Bronsky J, Mitrova K, Karpisek M, Mazoch J, Durilova M, Fisarkova B, Stechova K, Prusa R, Nevoral J, Adiponectin AFABP. Leptin in human breast milk during 12 months of lactation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:474–7.

Casabiell X, Piñeiro V, Tomé MA, Peinó R, Diéguez C, Casanueva FF. Presence of leptin in colostrum and/or breast milk from lactating mothers: a potential role in the regulation of neonatal food intake. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4270–3.

Khan S, Hepworth AR, Prime DK, Lai CT, Trengove NJ, Hartmann PE. Variation in fat, lactose, and protein composition in breast milk over 24 hours: associations with infant feeding patterns. J Hum Lact. 2013;29:81–9.

Schubring C, Englaro P, Siebler T, Blum WF, Demirakca T, Kratzsch J, Kiess W. Longitudinal analysis of maternal serum Leptin levels during pregnancy, at birth and up to six weeks after birth: relation to body mass index, Skinfolds, sex steroids and umbilical cord blood Leptin levels. Horm Res. 1998;50:276–83.

Pérez-Pérez A, Sánchez-Jiménez F, Maymó J, Dueñas JL, Varone C, Sánchez-Margalet V. Role of leptin in female reproduction. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53:15–28.

Catalano PM, Hoegh M, Minium J, Huston-Presley L, Bernard S, Kalhan S, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Adiponectin in human pregnancy: implications for regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1677–85.

Brunner S, Schmid D, Zang K, Much D, Knoeferl B, Kratzsch J, Amann-Gassner U, Bader BL, Hauner H. Breast milk leptin and adiponectin in relation to infant body composition up to 2 years. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10:67–73.

Edlow AG. Maternal obesity and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in offspring. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(1):95–110.

Rivera HM, Christiansen KJ, Sullivan EL. The role of maternal obesity in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:194.

Roberts VH, Frias AE, Grove KL. Impact of maternal obesity on fetal programming of cardiovascular disease. Physiology (Bethesda). 2015;30(3):224–31.

Santangeli L, Sattar N, Huda SS. Impact of maternal obesity on perinatal and childhood outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29(3):438–48.

Glavas MM, Kirigiti MA, Xiao XQ, Enriori PJ, Fisher SK, Evans AE, et al. Early overnutrition results in early-onset arcuate leptin resistance and increased sensitivity to high-fat diet. Endocrinology. 2010;151:1598–610.

Kirk SL, Samuelsson AM, Argenton M, Dhonye H, Kalamatianos T, Poston L, et al. Maternal obesity induced by diet in rats permanently influences central processes regulating food intake in offspring. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5870.

Morris MJ, Chen H. Established maternal obesity in the rat reprograms hypothalamic appetite regulators and leptin signaling at birth. Int J Obes. 2009;33(1):115–22.

Vickers MH, Sloboda DM. Leptin as mediator of the effects of developmental programming. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(5):677–87.

Coupe B, Grit I, Hulin P, Randuineau G, Parnet P. Postnatal growth after intrauterine growth restriction alters central leptin signal and energy homeostasis. PLoS One. 2012;7:30616.

Jaquet D, Leger J, Tabone MD, Czernichow P, Levy-Marchal C. High serum leptin concentrations during catch-up growth of children born with intrauterine growth retardation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(6):1949–53.

Yura S, Itoh H, Sagawa N, Yamamoto H, Masuzaki H, Nakao K, et al. Role of premature leptin surge in obesity resulting from intrauterine undernutrition. Cell Metab. 2005;1(6):371–8.

Wattez JS, Delahaye F, Lukaszewski MA, Risold PY, Eberlé D, Vieau D, et al. Perinatal nutrition programs the hypothalamic melanocortin system in offspring. Horm Metab Res. 2013;45(13):980–90.

Shehadeh N, Khaesh-Goldberg E, Shamir R, Perlman R, Sujov P, Tamir A, Makhoul IR. Insulin in human milk, postpartum changes and effect of gestational age. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F214–6.

Luoto R, Laitinen K, Nermes M, Isolauri E. Impact of maternal probiotic-supplemented dietary counseling during pregnancy on colostrum adiponectin concentration: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:339–44.

Ekelund U, Ong K, Linné Y, Neovius M, Brage S, Dunger DB, Wareham NJ, Rössner S. Upward weight percentile crossing in infancy and early childhood independently predicts fat mass in young adults: the Stockholm weight development study (SWEDES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:324–30.

Dennison BA, Edmunds LS, Stratton HH, Pruzek RM. Rapid infant weight gain predicts childhood overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:491–9.

Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C. Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. I. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1235–9.

Ong KK, Preece MA, Emmett PM, Ahmed ML, Dunger DB, Team AS. Size at birth and early childhood growth in relation to maternal smoking, parity and infant breast-feeding: longitudinal birth cohort study and analysis. Pediatr Res. 2002;52:863–7.

Putzker S, Bechtold-Dalla Pozza S, Kugler K, Schwarz HP, Bonfig W. Insulin resistance in young adults born small-for-gestational-age (SGA). J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27:253–9.

Boguszewski MC, Mericq V, Bergada I, Damiani D, Belgorosky A, Gunczler P, Ortiz T, Llano M, Domene HM, Calzada-Leon R, Blanco A, Barrientos M, Procel P, Lanes R, Jaramillo O. Latin American consensus: children born small-for-gestational-age. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:66.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the other researchers from NESCA group (Amanda Ferreira, Fabiana Copes, Mariana Lopes de Brito, Monique Cabral Hahn, Salete de Matos, Sara Brunetto, Tanara Vogel Pinheiro, Thamíris Medeiros). We also thank the participant families for their time and patience.

Funding

The research was supported by National Support Program for Centers of Excellence PRONEX/ FAPERGS 2009; PRONEM/FAPERGS 2011; CNPq; CAPES and FIPE/HCPA.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MN was responsible for designed and conducted research, analyzed data or performed statistical analysis, wrote paper, and had primary responsibility for final content and sample analysis. CHS was responsible for designed and conducted research and final review of paper. VLB was responsible for designed research. JRB was responsible for designed and conducted research. ICRW was responsible for designed and conducted research, wrote paper, and had primary responsibility for final content and sample analysis. MZG was responsible for designed and conducted research, analyzed data or performed statistical analysis, wrote paper and had primary responsibility for final content. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The procedures performed here are in accordance with the ethical standards of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre Research Ethics Committee with judgment number 11–0097 and by the Grupo Hospitalar Conceição Ethics Committee with judgment number 11–027. All participants gave their written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. Details that might disclose the identity of the subjects under study had been omitted.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nunes, M., da Silva, C.H., Bosa, V.L. et al. Could a remarkable decrease in leptin and insulin levels from colostrum to mature milk contribute to early growth catch-up of SGA infants?. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17, 410 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1593-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1593-0