Abstract

Background

Language barriers were reported to affect timely access to health care and outcome. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of language disparity on quality benchmarks of acute ischemic stroke therapy.

Methods

Consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke at the University of California Irvine Medical Center from 2013 to 2016 were studied. Patients were categorized into 3 groups according to their preferred language: English, Spanish, and other languages. Quality benchmarks and outcomes of the 3 language groups were analyzed.

Results

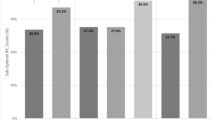

Of the 928 admissions, 69.7% patients recorded English as preferred language, as compared to 17.3% Spanish and 13.0% other languages. There was no significant difference in the rate of receiving intravenous thrombolysis (24.3, 22.1 and 21.0%), last-known-well to door time, door-to-imaging time, door-to-needle time, and hospital length of stay among the 3 language groups. In univariate analysis, the other languages group had lower chance of favorable outcomes than the English-speaking group (26.3% vs 40.4, p < 0.05) while the Spanish-speaking group had lower mortality rate than English-speaking group (3.1% vs 7.7%, p = 0.05). After adjusting for age and initial NIHSS scores, multivariate regression models showed no significant difference in favorable outcomes and mortality between different language groups.

Conclusion

We demonstrate no significant difference in quality benchmarks and outcome of acute ischemic stroke among 3 different language groups. Our results suggest that limited English proficiency is not a significant barrier for time-sensitive stroke care at Comprehensive Stroke Center.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) remains the only proven medical therapy for acute ischemic stroke (AIS) [1]. An analysis of pooled data from clinical trials found that earlier the patient receives tPA, better the chances of recovery [2]. IVT rates in Get-With-The-Guideline (GWTG)-Stroke-participating hospitals have improved significantly over time [3]. However, a recent study reported that up to 18% potentially eligible patients were not being treated with IVT [4]. After adjusting for stroke severity, minorities remained more likely to not receive treatment [4, 5]. Thus, identification of the practice hurdles and development of improved system of care should be a high priority for stroke research.

One of the possibilities for lower IVT rates in minorities could be language barriers. In the United States, 18.7% of the residents speak a language other than English at home and 8.4% residents have limited English proficiency [6]. In California, approximately 30% patients have limited English proficiency [7]. Language barriers were reported to affect timely access to health care and patient-physician communications [8,9,10,11,12].

Rostanski et al. investigated the language discordance between patients and physicians and found no effect of language discordance on door-to-imaging (DTI) time and door-to-needle (DTN) time [13]. Luan et al. analyzed single center data of 3894 AIS patients and found no significant difference in IVT rate between English and non-English-preferring patients [14]. However, previous studies reported conflicting results on the outcomes of patients with language disparity. Shah et al. analyzed data from the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network and showed reduced mortality and better performance on some quality of care measures in patients with language barriers [15]. In contrast, Kilkenny et al. examined data from the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry and showed that patient requiring interpreters had comparable discharge outcomes but poorer Health Related Quality of Life than patients not needing interpreters [16].

In this study, we sought to appraise whether language disparity affects IVT rate, time-sensitive quality benchmarks, and outcomes of AIS at a Joint Commission-certified Comprehensive Stroke Center in South California, where approximately 30% patients have limited English proficiency [7].

Methods

Patient population and study protocol: Consecutive patients admitted for AIS at the University of California Irvine Comprehensive Stroke Center from January 1st, 2013 to December 31st, 2016 were included in the study. The patient list was generated from the prospectively maintained American Heart Association (AHA) “Get-With-The-Guideline (GWTG)® Stroke” program at our hospital. The registry uses a web-based patient management tool to collect clinical data on consecutively admitted patients, to provide decision support, and to enable real-time online reporting features [17]. Patients with TIA, stroke mimics, subacute stroke, and inpatient stroke were excluded. The following data were collected from the registry and electronic medical record by experienced neurologists (AJ, NA, and SL): patient demographics, NIHSS scores, initial blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), last-known-well (LKW)-to-door time (LKW-DT), DTI time, DTN time for IV tPA, hospital length of stay (LOS), and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at hospital discharge. Laboratory results, including comprehensive metabolic panel, serum levels of lipids and glycol-hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) were also collected. A mRS score ≤ 2 was defined as favorable outcome. Patients were categorized into 3 groups according to their preferred language: English, Spanish, and other-languages (including Vietnamese, Korean, Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese, Punjabi, Romanian, Arabic, and Tagalog).

We have standard protocols for the management of patients with limited English proficiency. When the provider encounters language barrier, interpreter service will be requested for assistance. Spanish and Vietnamese interpreters were available Monday through Friday, 7:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. in the emergency room (ER). Whenever on-site interpreter was not available, tele-interpreter service was used for patient/provider communication. Telephonic or in-person interpreter was available 24/7 via phones or Video Remote Interpreter carts. Other healthcare providers and family members were used only when official interpreter service was declined or unavailable.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages (%), and continuous variables as mean plus standard deviation (SD). Tukey’s Studentized Range Test was used to estimate the differences in means with 95% confidence interval (CI) between different language groups. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to test the crude odds ratios (OR) (95% CI) of the benchmarks comparing with English-speaking patients. Multivariate logistic regression models were performed to determine the adjusted OR (95% CI) of favorable outcome (mRS 0–2) and mortality at hospital discharge, in association with the preferred language. In the multivariate logistic regression models, we adjusted for potential confounding factors (i.e., age and initial NIHSS scores). The SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform the data analysis.

Results

Nine-hundred twenty-eight AIS admissions were identified during the study period. In this single center cohort, 69.7% patients recorded English, 17.3% Spanish, and 13.0% other languages as preferred language. The ethnic compositions of the English group were 79.6% White, 12.7% Hispanic, 12.7% Asian, and 3.2% Black. The baseline characteristics of the 3 groups were summarized in Table 1. Compared with English-speaking group, Spanish-speaking patients were significantly younger (65 ± 14 vs. 69 ± 16, p < 0.05) while other language-speaking patients were significantly older (75 ± 12 vs. 69 ± 16, p < 0.05) and had more women (55.5% vs. 45.1%, p < 0.05). Both Spanish-speaking and other language-speaking groups had significantly lower BMI than the English-speaking group. In contrast, the other languages-speaking group had significantly higher levels of HbA1c than English-speaking and Spanish-speaking groups. There was no significant difference in initial blood pressures and LDL cholesterol levels at admission among the 3 groups.

The stroke severity and quality benchmarks of stroke care were shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in initial NIHSS scores, DTI time, IVT rate, and LOS among the 3 language groups. Compared to English-speaking group, the other language-speaking group had lower chances of favorable outcomes (26.3% vs 40.0%; OR, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.4–0.8]; p = 0.01) while the Spanish-speaking group had lower mortality rate (3.1% vs 7.7%, OR, 0.4 [95 CI, 0.1–1.0]; p = 0.04).

To eliminate any potential confounding factors, multivariate logistic regression model was performed to assess the relationship between preferred languages and clinical outcomes (Table 3). After adjusting for age and initial NIHSS scores, there was no significant difference in favorable outcome at hospital discharge between the 3 language groups. With each point increase in NIHSS score or each year increase in age, the patients were 14% or 3% less likely to have favorable outcome at hospital discharge, respectively. Likewise, after adjusting for age and initial NIHSS scores, the Spanish-speaking group did not have lower mortality rate than the English-speaking group (OR, 0.44 [95% CI, 0.17–1.18]; p = 0.10). Higher initial NIHSS score was correlated with higher mortality rate (OR, 1.15[95% CI, 1.11–1.19]; p < 0.0001). To follow the Principle of Parsimony in variable selections, we stopped adding other variables in the multivariable logistic regression analysis afterwards.

Among the 218 patients who were treated with IVT, there was no significant difference in LKW-DT, DTI time, DTN time, hospital LOS, favorite outcome and mortality between English and Spanish or other language groups (Table 4). Language disparity has no significant effect on time-sensitive quality benchmarks of IVT.

Discussion

Ethnic minorities in the United States may have limited English proficiency and substandard care due to language barriers. However, previous studies have showed conflicting results on the impact of language barriers. Emergency medical service usage was actually reported higher in the Spanish-speaking patients than the English-speaking patients treated with IVT [18]. A retrospective single-center study showed that language discordance was not associated with acute stroke misdiagnosis among patients treated with IVT [19]. Another study reported reduced mortality in patients with language barriers [13]. The possible explanations for reduced mortality, however, were likely due to inclusion of patients with TIA and family desire for aggressive intervention over quality of life [13, 20].

The AHA quality improvement initiatives and the Comprehensive Stroke Center certification have improved stroke care in recent years (https://www.jointcommission.org/certification/advanced_certification_comprehensive_stroke_centers.aspx) [3, 21,22,23], Patients with limited English proficiency may receive similar quality of care as English-speaking patients at Comprehensive Stroke Centers partly due to the rigorous re-certification requirement for ongoing performance improvement in stroke care. The Comprehensive Stroke Center re-certification is conducted by the Joint Commission every 2 years. At the re-certification site visit, the surveyors assess the ongoing quality improvement in 18 core quality measures (including DTN time) and opportunities for further improvement (e.g., language disparity and availability of interpreter service). The re-certification citations on any deficiency or opportunities for improvement often lead to additional support for better stroke care, such as 24/7 availability of interpreter service and hiring of additional fellows or nurse practitioner.

In the current study, we demonstrate that there is no significant difference in quality benchmarks, IVT rate, and outcomes of AIS among 3 language groups at an academic Comprehensive Stroke Center.

The diversity of healthcare providers and interpreter/tele-interpreter service may have overcome language barriers. Our IVT rate and DTN time are comparable or better than what were reported recently from other Comprehensive Stroke Centers [14, 19, 21, 22, 24]. We have also shown that increased age and higher initial NIHSS scores were associated with unfavorable outcomes at hospital discharge.

The strengths of the current study include: 1). The study was performed at a Comprehensive Stroke Center in a region with significant language disparity. 2). Our data reflects current standard care at academic Comprehensive Stroke Centers in the United States. 3). Univariate and multivariate regression models were performed to investigate the language disparity as potential barrier for time-sensitive quality benchmarks and outcomes.

Our study has a few limitations. First, due to lack of long-term follow-up data, we were only able to investigate the effects of language disparity on outcomes at hospital discharge. Second, the retrospective study was unable to determine the specific contribution of interpreters and tele-interpreter service to the improvement of stroke care in patients with language barriers. Third, at our medical center, all ER personnel and providers speak English as official language. Some of them may speak Spanish or other languages fluently. However, in this retrospective study, we do not have data on languages spoken by hospital staff and how fluently family members are who provided the history and helped coordinate care. Finally, patients with a preferred language other than English do not necessarily communicate ineffectively in English. In this retrospective study, we do not have information on how patients’ proficiency in English was assessed and cannot determine how many patients indeed needed language interpretation.

Conclusion

In this single center study, we demonstrate no significant difference in IVT rate, quality benchmarks, and outcome of AIS among 3 language groups. Our findings suggest that limited English proficiency is not a significant barrier for acute stroke care at Comprehensive Stroke Center.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available, but data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIS:

-

acute ischemic stroke

- BMI:

-

body mass index;

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- DTI:

-

door-to-imaging

- DTN:

-

door-to-needle

- HbA1c:

-

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- LDL-c:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LKW-TD:

-

Last-known-well-to-door

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- mRS:

-

modified Rankin scale

- NIHSS:

-

National Institutes of Health stroke scale

- OR:

-

odds ratios

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- tPA:

-

tissue plasminogen activator

References

Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46–e110.

Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, Brott TG, Toni D, Grotta JC, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: An updated pooled analysis of ecass, atlantis, ninds, and epithet trials. Lancet (London, England). 2010;375:1695–703.

Schwamm LH, Ali SF, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, Saver JL, Messe S, et al. Temporal trends in patient characteristics and treatment with intravenous thrombolysis among acute ischemic stroke patients at get with the guidelines–stroke hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:543–9.

Messé SR, Khatri P, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, Saver JL, Bhatt DL, et al. Why are acute ischemic stroke patients not receiving IV tPA? Results from a national registry. Neurology. 2016;87:1565–74. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003198.

Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:229–31.

Zong J, Batalova J. The Limited English Proficient Population in the United States. [published online July 8, 2015]. Migration Policy Institute 2015.

Proctor, K., Wilson-Frederick, S & Haffer, S. C. (2018). The limited English proficient population: Describing Medicare, Medicaid and dual beneficiaries. Health Equity 2(1), 82–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2017.0036.

Aparicio HJ, Carr BG, Kasner SE, Kallan MJ, Albright KC, Kleindorfer DO, et al. Racial disparities in intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator use persist at primary stroke centers. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001877.

Cruz-Flores S, Rabinstein A, Biller J, Elkind MS, Griffith P, Gorelick PB, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in stroke care: the american experience: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42:2091–116.

van Rosse F, de Bruijne M, Suurmond J, Essink-Bot ML, Wagner C. Language barriers and patient safety risks in hospital care a mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;54:45–53.

Taylor E, Jones F. Lost in translation: exploring therapists' experiences of providing stroke rehabilitation across a language barrier. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:2127–35.

Timmins CL. The impact of language barriers on the health care of latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2002;47:80–96.

Shah BR, Khan NA, O'Donnell MJ, Kapral MK. Impact of language barriers on stroke care and outcomes. Stroke. 2015;46:813–8.

Kilkenny MF, Lannin NA, Anderson CS, Dewey HM, Kim J, Barclay-Moss K, AuSCR Consortium. Quality of life is poorer for patients with stroke who require an interpreter: an observational Australian registry study. Stroke. 2018;49:761–4.

Rostanski SK, Stillman J, Williams O, Marshall RS, Yaghi S, Willey JZ. The influence of language discordance between patient and physician on time-to-thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Neurohospitalist. 2016;6:107–10.

Luan Erfe B, Siddiqui KA, Schwamm LH, Mejia NI. Relationship Between Language Preference and Intravenous Thrombolysis Among Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(12):e003782. Published 2016 Nov 23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003782.

Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Pan W, Frankel MR, Smith EE, et al. Get with the guidelines-stroke is associated with sustained improvement in care for patients hospitalized with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation. 2009;119:107–15.

Rostanski SK, Kummer BR, Miller EC, Marshall RS, Williams O, Willey JZ. Impact of Patient Language on Emergency Medical Service Use and Prenotification for Acute Ischemic Stroke. Neurohospitalist. 2019;9:5–8.

Rostanski SK, Williams O, Stillman JI, Marshall RS, Willey JZ. Language barriers between physicians and patients are not associated with thrombolysis of stroke mimics. Neurology Clin Practice. 2016;6:389–96.

Kelly AG, Hoskins KD, Holloway RG. Early stroke mortality, patient preferences, and the withdrawal of care bias. Neurology. 2012;79:941–4.

Xian Y, Xu H, Lytle B, Blevins J, Peterson ED, Hernandez AF, et al. Use of strategies to improve door-to-needle times with tissue-type plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke in clinical practice: findings from target: stroke. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality Outcomes. 2017;10:e003227. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003227.

Man S, Zhao X, Uchino K, Hussain MS, Smith EE, Bhatt DL, Xian Y, Schwamm LH, Shah S, Khan Y, Fonarow GC. Comparison of acute ischemic stroke care and outcomes between comprehensive stroke centers and primary stroke centers in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(6):e004512.

Weimar C, Konig IR, Kraywinkel K, Ziegler A, Diener HC. Age and national institutes of health stroke scale score within 6 hours after onset are accurate predictors of outcome after cerebral ischemia: development and external validation of prognostic models. Stroke. 2004;35:158–62.

Luan Erfe BM, Siddiqui KA, Schwamm LH, Kirwan C, Nunes A, Mejia NI. Professional medical interpreters influence the quality of acute ischemic stroke care for patients who speak languages other than english. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9):e006175. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006175.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from the University of California Irvine Xiaoqi Cheng & Dongmei Liao International Stroke Research Scholarship.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NA, AJ and SL: Concept, design, data analysis, and draft of the manuscript. LF: Concept of the study and editing of the draft. DS: Concept and data acquisition. WY: Concept, design, data analysis, editing and final revision of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a retrospective observational study. It was approved by the University of California Irvine Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Ethics Committee (IRB # 2017–3438). Informed consents were waived by our IRB due to minimal risk of harm to the patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Yu has received compensation for activities with Stryker and Amgen as a scientific consultant. However, the activities are not related to this research project. Other authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, N., Janarious, A., Liu, S. et al. Language disparity is not a significant barrier for time-sensitive care of acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol 20, 363 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01940-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01940-9