Abstract

Background

Eosinophilic peritonitis is a relatively rare entity. Kimura’s disease is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology, characterized by subcutaneous nodules mainly in the head and neck region, regional lymphadenopathy and occasional involvement of kidney. There is currently no report of eosinophilic peritonitis in Kimura’s disease.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old Chinese man presented with abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting and edema in lower limbs for 1 month. Laboratory data showed elevated eosinophils in peripheral blood and ascites, nephrotic syndrome with progressively renal dysfunction, and elevated IgE. Ultrasonography of lymph nodes showed multiple lymphadenopathy in bilateral inguinal regions. Surgical excision was performed for one of the enlarged lymph nodes and histopathology revealed diagnosis of Kimura’s disease. Renal biopsy indicated focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis with infiltration of eosinophils in renal interstitium. The patient was prescribed with oral prednisolone therapy (30 mg/day), and underwent continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). The peripheral and peritoneal eosinophil count decreased rapidly and normalized within 2 days. Forty-five days after prednisolone therapy, partial remission of nephrotic syndrome and decrease of serum creatinine were achieved while peritoneal dialysis dosage had decreased. Inguinal lymph nodes gradually shrunk in size. The overall conditions remain stable afterwards.

Conclusions

This rare case highlighted the clinical conundrum of a patient presenting with eosinophilic peritonitis, lymphadenopathy, nephrotic syndrome and renal failure associated with Kimura’s disease. The remarkable eosinophilia, pathology of lymph node and kidney, as well as significant response to steroids should guide towards the diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eosinophilic peritonitis is a relatively rare entity. The etiology of eosinophilic peritonitis is multifactorial, mostly being reported in patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, parasitic and fungal infections, hypereosinophilic syndrome and less common diseases including malignancy, hematological disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disease and peritoneal dialysis [1,2,3]. Kimura’s disease is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology, characterized by subcutaneous nodules mainly in the head and neck region, regional lymphadenopathy and occasional involvement of the major salivary glands and kidney. It is often accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia and markedly elevated serum IgE levels [4]. There is currently no report of eosinophilic peritonitis in Kimura’s disease. Here is a case of eosinophilic peritonitis manifested by Kimura’s disease accompanied with nephrotic syndrome.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old man was admitted to the hospital and reported abdominal distention, with positive shifting dullness and edema in lower limbs. He also complained of acid regurgitation, nausea, and vomiting for 1 month, without fever, abdominal pain, rash, or oliguria. He had been prescribed with penicillin for a week without remission. The patient had history of edema and was diagnosed as nephrotic syndrome 22 years ago but didn’t undergo renal biopsy. He was treated with 60 mg/day prednisone for almost 1 year and tapered to cease until negative proteinuria, while intermittently taking moderate dose of prednisone afterwards whenever urine dipsticks showed positive proteinuria by September 2018. However, he didn’t monitor blood routine examination and serum creatinine. He denied history of asthma, atopy and family history of kidney diseases. The patient was a non-smoker and denied alcohol ingestion. On physical examination, his blood pressure was normal, and cardiopulmonary examination was sound. There was one palpable lymph nodal mass in each side of inguinal region, both were non-tender and firm in consistency, with normal overlying skin.

On admission, laboratory data showed nephrotic syndrome with peripheral eosinophilia at 2.1 × 109/L (24.3%) and elevated IgE (171 IU/L). Stool analysis for parasitic eggs and parasites didn’t show abnormalities. Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated a maximum 10 cm depth of ascites. Computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple mesentery exudation, thickened peritoneum, and ascites, without hepatosplenomegaly, intra- and extra-hepatic bile ducts dilation and intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy. Diagnostic abdominal paracentesis revealed translucent yellow fluid. The white cell count in the ascitic fluid was 200/mm3, with 14% eosinophils. Chemical analysis indicated transudate with serum-acites albumin gradient (SAAG) of 15.4 g/L. Ascitic fluid smears and cultures for bacterial, tuberculous and fungus were negative. Serum immunoglobulin (IgG) level was low, while IgA, IgM, C3 and C4 level was normal. Serum and urine immunofixation electrophoresis showed monoclonal IgG λ, with normal free κ/λ ratio in serum. Bone marrow cytology, histopathology and flow cytometry showed no abnormality.

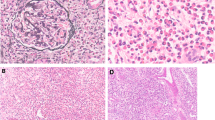

Serum albumin was 18 g/L, 24-h proteinuria was 13.9 g/day (urine volume 1450 ml). Serum creatinine (Scr) progressively elevated from 472 μmol/L to 612 μmol/L within 8 days before admission to hospital, and the peak Scr was 844 μmol/l on 14th day after admission. Serum IgG4 was in the normal range. Anti-PLA2R, anti-dsDNA, ANCA and anti-GBM antibody were all negative. Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated relatively small size of kidney. Due to the progressively increasing Scr, peritoneal dialysis was performed to relieve uremia symptoms and drainage ascites. Ultrasound-guided renal biopsy was performed. Twenty-eight glomeruli were included in the specimens for light microscopy. Of them, 17 glomeruli were ischemic global sclerosis, 9 glomeruli had segmental glomerulosclerosis with adhesion. Patchy interstitial inflammation of lympoytes, mononuclear cells along with eosinophilils. Immmunofluorescence showed focal IgM ++, C3 +++ in mesangium and segmental sclerosis of glomeruli. The electron microscopy demonstrated diffuse effacement of podocytic foot processes without electron dense deposits. Final pathological diagnosis was focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. There were no signs for IgG4 related disease or monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS) (Fig. 1).

Renal pathology features. Renal specimen showed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, acute tubularinterstitial nephritis with red blood cell and protein casts in tubules and eosinophilic infiltration in renal interstitium. Electron microscope showed no electron dense deposit. (a: PAS + MASSON × 400; b: PAS × 200; c: HE × 400; d: HE × 400; e: EM × 5000; f: EM × 3000)

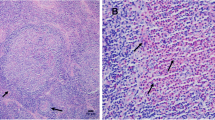

Ultrasonography of lymph nodes showed multiple lymphadenopathy in bilateral inguinal regions, with the largest measuring about 2.6 × 0.9 cm in the left inguinal region, and 2.7 × 0.8 cm in the right inguinal region (Fig. 2). Screening for HIV, Syphilis, cytomegalovirus (CMV), epstein-barr virus (EBV) and evaluation of interferon-gamma release assay for tuberculosis didn’t show abnormalities. Screen for toxoplasmosis was not performed, since he didn’t have epidemiological history of toxoplasmosis. Surgical excision was performed for one of the enlarged lymph nodes (1.5 cm in diameter) in the right inguinal region. Microscopic examination of H&E-stained sections showed preserved lymph node architecture, follicular and interfollicular hyperplasia, as well as increased eosinophils with formation of eosinophilic microabscesses within the germinal centers (Fig. 3). The histopathology of lymph node didn’t show caseous granuloma or other infectious features, such as toxoplasmic lymphadenitis. Hence, a diagnosis of Kimura’s disease was established with relevant clinical details and specific histopathological features.

Based on the clinical data, the eosinophilic peritonitis, nephrotic syndrome and lymphadenopathy was considered to be associated with systematic involvement of Kimura’s disease. The patient was prescribed with oral prednisolone therapy (30 mg/day), and underwent continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). Anti- infective therapy wasn’t administered. The peripheral and peritoneal eosinophil count decreased rapidly and normalized within 2 days. Forty-five days after prednisolone therapy, 24-h proteinuria reduced to 2.3 g/d (Urine volume 1500 ml), and serum albumin level increased to 31 g/L. Serum creatinine decreased gradually to around 350 μmol/L while peritoneal dialysis dosage had decreased from 4500 ml/d to 3000 ml/d. It’s noteworthy that residual urea clearance (Kt/V) gradually increased to 2.77. Inguinal lymph nodes gradually shrunk in size, with the largest measuring about 1.9 × 0.6 cm in the left inguinal region, and 2.4 × 0.5 cm in the right inguinal region. Prednisolone was tapered to 25 mg/d and peritoneal dialysis dosage decreased from 3000 ml/d to 1500 ml/d after 60 days. The overall conditions maintained stable afterwards (Table 1).

Discussion and conclusions

We present a case of elevated eosinophils in peripheral blood and ascites, nephrotic syndrome with progressively renal dysfunction and lymphadenopathy. Several diseases presenting with eosinophilia, nephrotic lesions and lymphadenopathy must be differentiated from Kimura’s disease, including acute interstitial nephritis, lymphoma, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal protein and skin syndrome (POEMS), IgG4 related disease. In this case, lymph node pathology and renal biopsy plays an important role in distinguishing it from other diseases. Another important differential diagnosis of Kimura’s disease is angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophils (ALHE), which is also called as epithelioid hemangioma (EH) nowadays. EH/AHLE and Kimura’s disease can share similar clinical and morphological features, and they were once considered different stages of the same disease. Peripheral eosinophilia, elevated IgE, lymphadenopathy and nephrotic syndrome is more common seen in Kimura’s disease than EH/ALHE. Difference of histopathological features helps to distinguish this entity. Histologically, florid lymphoid follicles with germinal center formation, eosinophilic infiltrates, eosinophilic microabscesses, and eosinophilic folliculolysis are salient features of Kimura’s disease, the histiocytoid/ epithelioid-endothelial cells are characteristic of ALHE/EH [5, 6].

Eosinophilic peritonitis is a relatively rare entity defined as the presence of > 100 eosinophils/mm3, or > 10% eosinophils of the total non-erythrocyte count [7]. A recent systematic review reported in patients with eosinophilic peritonitis, 74% had eosinophilic gastroenteritis, 10% parasitic and fungal infections, 7% hypereosinophilic syndrome and 9% patients with less common diseases (eosinophilic pancreatitis, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, myelofibrosis, T-cell lymphoma, Churg Strauss syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, familial paroxysmal polyserositis and Ménétrier’s disease) [1,2,3]. However, there is currently no report of Kimura’s disease with eosinophilic peritonitis among general population. Therapy with corticosteroids results in resolution in almost all patients with eosinophilic ascites [1]. In this case, eosinophil counts in ascites correlated with peripheral blood eosinophil counts, both decreased to normal after receiving corticosteroids therapy, similar to previous studies [7].

Nephrotic syndrome has been reported as a complication of Kimura’s disease, including membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease, diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and membrane proliferative glomerulonephritis [8], with a few FSGS cases [9,10,11]. Steroid monotherapy has been used for Kimura’s disease and FSGS with varying degrees of success [9,10,11,12]. In this case, the patient was steroid-sensitive on remission of eosinophils, eosinophilic peritonitis, lymph nodes and partial remission of renal damage, which was clinically considered to be associated with systematic involvement of Kimura’s disease, however without stronger evidence, and needs long-term follow-up. Association between Kimura’s disease and renal involvement remains unclear. Previous studies suggest that the predominance of Th2 and Tc1 cells and certain cytokines including IL-5 as an eosinophil-active cytokine and IL-10 may contributes to the pathogenesis of Kimura’s disease, but further research is warranted [13,14,15].

This patient had elevated IgG λ in serum and urine in the absence of plasma cell or lymphoid malignancy or end organ damage, therefore monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) was determined [16]. Though there is currently no report of Kimura’s disease with MGUS, lymphatic proliferative disease is cautious to be ruled out.

Nowadays, there is no consensus regarding the optimal treatment for Kimura’s disease. Systemic corticosteroids was chosen for this patient because of the associated nephrotic syndrome.

In conclusion, the rare case highlighted the clinical conundrum of a patient presenting with eosinophilic peritonitis, lymphadenopathy, nephrotic syndrome and renal failure associated with Kimura’s disease. Prompt treatment led to early remission, however kidney function was not completely recovered. Advantage of the study is timely diagnosis and proper differential diagnosis, the remarkable eosinophilia, pathology of lymph node and kidney, as well as significant response to steroids should guide towards the diagnosis.

Availability of data and materials

All data related to this case report are within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CAPD:

-

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- SAAG:

-

Serum-acites albumin gradient

- Ig:

-

Immunoglobulin

- Scr:

-

Serum creatinine

- MGRS:

-

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance

- MGUS:

-

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

- ALHE:

-

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophils

- EH:

-

Epithelioid hemangioma

- FSGS:

-

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis;

References

Pinte L, Baicuş C. Causes of eosinophilic ascites – A systematic review. Rom J Intern Med. 2019;57(2):110–24.

Khalil H, Joseph M. Eosinophilic ascites: a diagnostic challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016216791. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-216791.

Lee S, Schoen I. Eosinophilia of peritoneal fluid and peripheral blood associated with chronic peritoneal dialysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1967;47:638–40.

Kuo TT, Shih LY, Chan HL. Kimura’s disease: involvement of regional lymph nodes and distinction from angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:843–54.

Chun SI, Ji HG. Kimura’s disease and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: clinical and histopathologic differences. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:954–8.

Googe PB, Harris NL, Mihm MC Jr. Kimura’s disease and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia: two distinct histopathological entities. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14(5):263–71.

AbdullGaffa B. Eosinophilic effusions: a clinicocytologic study of 12 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46(12):1015-21.

Rajpoot DK, Pahl M, Clark J. Nephrotic syndrome associated with Kimura disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:486–8.

Dede F, Ayli D, Atilgan KG, Yüksel C, Duranay M, Sener D, Türker F. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis associating Kimura disease. Ren Fail. 2005;27(3):353–5.

Lu HJ, Tsai JD, Sheu JC, Tzen CY, Tsai TC, Lin CC, Huang FY. Kimura disease in a patient with renal allograft failure secondary to chronic rejection. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(10):1069–72.

Senel MF, Buren CT, Etheridge WB, Barcenas C, Jammal C, Kahan BD. Effects of cyclosporine, azathioprine and prednisone on Kimura’s disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in renal transplant patients. Clin Nephrol. 1996;45:18–21.

Loymans RJ, Berend K, Abreu de Martinez VG, Florquin S, de Vries AP. Nephrotic syndrome in Kimura's disease: apropos a case of the glomerular tip lesion in an African-Caribbean male. NDT Plus. 2011;4(1):60–2.

Ohta N, Fukase S, Suzuki Y, Ito T, Yoshitake H, Aoyagi M. Increase of Th2 and Tc1 cells in patients with Kimura’s disease. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38:77–82.

Motegi S, Hattori M, Shimizu A, Abe M, Ishikawa O. Elevated serum levels of TARC/CCL17, Eotaxin-3/CCL26 and VEGF in a patient with Kimura’s disease and prurigo-like eruption. Acta Derm Venerol. 2014;94:112–3.

Hosoki K, Hirayama M, Kephart GM, Kita H, Nagao M, Uchizono H, Toyoda H, Senba Y, Imai Y, Komada Y, Ihara T, Fujisawa T. Elevated numbers of cells producing interleukin-5 and interleukin-10 in a boy with Kimura disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;158:70–4.

Sethi S, Rajkumar SV, D’Agati VD. The complexity and heterogeneity of monoclonal immunoglobulin-associated renal diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(7):1810–23.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient for providing permission to share his information.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BXY and ZKY collected and synthesized the data and wrote the manuscript. DS, ZW, DMX, SXW, LN, FDZ and JD reviewed and edited the manuscript. SXW and LN reviewed and revised pathology. ZKY and JD contributed to the design of this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the consent form is available for review and can be provided on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, B., Yang, Z., Song, D. et al. Eosinophilic peritonitis and nephrotic syndrome in Kimura’s disease: a case report and literature review. BMC Nephrol 21, 138 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01791-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-020-01791-z