Abstract

Background

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) glomerulonephritis does not usually coexist with another glomerulonephritis such as IgA nephropathy. We present a rare case having a combination of these two diseases, and furthermore, histological evaluation could be performed before and after the development of anti-GBM glomerulonephritis over a period of only10 months.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old woman was admitted with complaints of microscopic hematuria and mild proteinuria for the past 3 years. Serum creatinine level was normal at that time. The first renal biopsy was performed. Light microscopy revealed mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with fibro-cellular crescents in one out of 18 glomeruli, excluding one global sclerotic glomerulus. Immunofluorescence (IF) showed IgA and C3 deposition in the mesangium. Therefore, the diagnosis was IgA nephropathy. Eight months later, the patient’s serum creatinine suddenly rose to 4.53 mg/dL and urinalysis showed 100 red blood cells per high power field with nephrotic range proteinuria (12.3 g/gCr). The serological tests revealed the presence of anti-GBM antibody at the titer of 116 IU/mL. Treatments were begun after admission, consisting of hemodialysis, plasma exchange, and intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy. At 4 weeks after admission, the second renal biopsy was performed. Light microscopy revealed crescents in 18 of 25 glomeruli, excluding six global sclerotic glomeruli. IF showed linear IgG deposition along the GBM in addition to granular IgA and C3 deposition. Based on these findings, the diagnosis of anti-GBM glomerulonephritis and IgA nephropathy was confirmed. Renal function was not restored despite treatment, but alveolar hemorrhage was prevented.

Conclusions

We report a patient with a diagnosis of anti-GBM disease during the course of IgA nephropathy. This case strongly suggests that the presence of autoantibodies should be checked to rule out overlapping autoimmune conditions even in patient who have previously been diagnosed with chronic glomerulonephritis, such as IgA nephropathy, who present an unusually rapid clinical course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) glomerulonephritis is an autoimmune glomerular disease that is characterized by linear deposition of IgG along the GBM. The main target of anti-GBM antibody had been shown to lie in the NC1 domain of α3 chains of type IV collagen on the GBM. Histologically, it is associated with extensive crescent formation and clinically with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN). There are well-known associations between anti-GBM glomerulonephritis and the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and between anti-GBM glomerulonephritis and membranous nephropathy [1,2,3]. In a limited number of cases, anti-GBM glomerulonephritis has been associated with IgA nephropathy and other immune complex glomerulonephritis [4,5,6].

Herein, we report a patient with a diagnosis of anti-GBM disease during the course of IgA nephropathy.

Case presentation

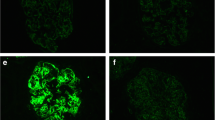

A 66-year-old woman with a significant past medical history of well-controlled hypertension was admitted with complaints of microscopic hematuria and mild proteinuria for the past 3 years. Serum creatinine level was within normal range at that time and therefore the anti-GBM antibody was not tested. The first renal biopsy revealed mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with fibro-cellular crescents in one out of 18 glomeruli, excluding one global sclerotic glomerulus (Fig. 1a), and deposition of IgA and C3 in mesangial areas by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2a). Weak but significant IgG deposition was also observed in glomeruli in the distribution somewhat different from IgA or C3 (Fig. 2a). The electron-dense deposits were observed in mesangial areas by electron microscopy. Therefore, the diagnosis was IgA nephropathy. Antihypertensive therapy was initiated, mainly with an RAS inhibitor. Eight months later, the patient’s serum creatinine suddenly rose to 4.53 mg/dL (it was 1.04 mg/dL from the routine blood test 1 month before). Urinalysis showed 100 red blood cells per high power field and urinary protein excretion of 12.3 g/gCr (Fig. 3). The serological tests that were performed to differentiate the cause of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis revealed the presence of anti-GBM antibody at the titer of 116 IU/mL and the absence of anti-nuclear antibody and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Laboratory findings on admission are summarized in the Table 1.

Representative photographs of Periodic acid-Schiff stained sections (Scale bars = 50.0 μm). a First renal biopsy showing mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with fibro-cellular crescent in one glomerulus. b Second renal biopsy showing diffuse crescent formation and a few residual glomerular tufts. Scale bars = 50.0 μm

Representative photographs of immunofluorescence staining (Scale bars = 20.0 μm). a First renal biopsy showing positive staining of IgA, IgG, and C3. The staining pattern was similar in IgA and C3 (granular deposition probably in the mesangial area), but was rather different in IgG. b Second renal biopsy showing linear immunofluorescence for IgG along the glomerular capillary walls. IgA staining was found in mesangial areas, whereas C3 deposition was observed in mesangial areas as well as partially in the glomerular capillary walls

After admission, treatments with hemodialysis, plasma exchange, and intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy followed by oral prednisolone at the dose of 50 mg/day were initiated. The second renal biopsy was performed at 4 weeks after admission in order to assess the probability of renal recovery and to make the final diagnosis. It revealed cellular to fibrocellular crescents in 18 of 25 glomeruli, excluding six global sclerotic glomeruli by light microscopy. By immunofluorescence study, linear IgG deposition along the glomerular capillary walls and mesangial staining for IgA were observed. On the other hand, C3 deposition was observed in the mesangium as well as in the glomerular capillary walls (Fig. 2b). Electron-dense deposits were observed in mesangial areas, similarly as in the first biopsy, by electron microscopy (Fig. 4). Based on the aforementioned findings, the diagnosis of anti-GBM glomerulonephritis and IgA nephropathy was confirmed. Plasmapheresis was performed eight times, anti-GBM antibody gradually decreased, and alveolar hemorrhage was prevented. However, her renal function could not be restored and she underwent maintenance hemodialysis (Fig. 5).

Additional immunosuppressant was not given because the patient did not show any sign of pulmonary involvement and because the renal recovery was quite unlikely from clinical (continuous oliguria and hemodialysis dependence) as well as histological (crescent formation in most of non-sclerotic glomeruli) point of view.

Clinical and histological presentations from IgA nephropathy (at the time of first renal biopsy) and from anti-GBM disease (at the time of second renal biopsy) were summarized in the Table 2.

Discussion and conclusions

IgA nephropathy is an immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis defined immunohistologically by the presence of glomerular mesangial IgA deposits accompanied by a variety of histopathologic lesions, including mesangial proliferation [7]. Anti-GBM disease is caused by antibodies reactive to the glomerular and alveolar basement membrane.

The causal relationship of anti-GBM glomerulonephritis and IgA nephropathy is unclear. There was one hypothesis that the IgA-related immune complex might promote immunologic and inflammatory events, resulting in conformational changes and exposure of the GBM antigens leading to development of anti-GBM antibody [4]. However, it is difficult to prove whether anti-GBM disease in this patient developed as an incidental complication or was secondary to IgA nephropathy because there is still no established marker to distinguish primary from secondary anti-GBM disease. In this regard, we performed immunofluorescence staining for IgG subclasses on the second renal biopsy, and found that IgG4 was the main subclass of IgG bound to GBM in this patient (Fig. 6). The main subclass of pathogenic IgG in anti-GBM disease was reported to be usually IgG1 [8]. Whether predominance of IgG4 relates with anti-GBM disease developed secondary to IgA nephropathy deserves future study.

The pathophysiological condition of anti-GBM disease before clinical presentation is unknown. In this regard, Olson et al. conducted a case-control study involving 30 patients diagnosed with anti-GBM disease using serum samples from the Department of Defense Serum Repository. In the report, 13% (4 of 30) of study subjects had an elevated anti-GBM antibody level 2–10 months prior to diagnosis [9]. In the present case, multiple immunofluorescence labelling on the first biopsy showed partial linear IgG deposition along the glomerular capillary walls (Fig. 7). Although it may be only speculation because serum anti-GBM antibody was not tested at the time of the first biopsy, the patient might have had complications from asymptomatic (subclinical) anti-GBM disease at that point.

In the case of IgA nephropathy complicated by anti-GBM disease, Yamaguchi et al. speculated that the pathological features of IgA nephropathy may not be observed because the number of glomeruli free from destruction is very limited [10]. Therefore, the coexistence of anti-GBM glomerulonephritis and IgA nephropathy may be more frequent than is being reported.

In summary, we reported a patient with a diagnosis of anti-GBM disease during the course of IgA nephropathy. Histological evaluation could be performed before and after the development of anti-GBM disease over a period of 10 months. Even if the patient had already received a diagnosis of a chronic glomerulonephritis such as IgA nephropathy, we should check autoantibodies to rule out overlapping autoimmune conditions in case the patient showed an unusually rapid clinical course.

Abbreviations

- ANCA:

-

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- GBM:

-

Glomerular basement membrane

- IF:

-

Immunofluorescence

- RPGN:

-

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

References

Hellmark T, Niels JL, Collins AB, McCluskey RT, Brunmark C. Comparison of anti-GBM antibodies in sera with or without ANCA. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:376–85.

Petterson E, Törnroth T, Miettinen A. Simultaneous anti-glomerular basement membrane and membrounous glomerulonephritis: case report and literature review. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1984;31:171–80.

Kielstein JT, Helmchen U, Netzer KO, Weber M, Haller H, Floege J. Conversion of Goodpasture’s syndrome into membranous glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2082–5.

Trpkov K, Abdulkareem F, Jim K, Solez K. Recurrence of antiGBM antibody disease twelve years after transplantation associated with de novo IgA nephropathy. Clin Nephrol. 1998;49:124–8.

Xu D, Wu J, Wu J, Xu C, Zhang Y, Mei C, Gao X. Novel therapy for anti-glomerular basement membrane disease with IgA nephropathy: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11:1889–92.

Cui Z, Zhao MH, Wang SX, Liu G, Zou WX, Wang HY. Concurrent antiglomerular basement membrane disease and immune complex glomerulonephritis. Ren Fail. 2006;28:7–14.

Emancipator SN. IgA nephropathy:morphologic expression and pathogenesis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:461–2.

Hemminger J, Nadasdy G, Satoskar A, Brodsky SV, Nadasdy T. IgG subclass staining in routine renal biopsy material. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(5):617–26.

Olson SW, Arbogast CB, Baker TP, Owshalimpur D, Oliver DK, Abbott KC, Yuan CM. Asymptomatic autoantibodies associate with future anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1946–52.

Yamaguchi H, Takizawa H, Ogawa Y. A case report of the anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis with mesangial IgA deposition. CEN Case Rep. 2013;2:6–10.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our colleague Sachiko Iwama for excellent technical assistance in histological analysis. Part of this case report was previously presented at the 18th International Vasculitis & ANCA Workshop and was published in abstract form (Rheumatology 56, suppl 3, iii 81, 2017).

Funding

No funding supports.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK and GH diagnosed, treated, and clinically monitored the patient. TK performed the literature search and wrote the paper. SK, TOshima, KS, TT, NY, and MY participated in treatment and diagnosis of the patient during the hospitalization period. TOda performed the multiple immunofluorescence staining on the renal biopsy and helped to write the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of clinical information including symptom, laboratory data, histological findings and any accompanying images as a case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kojima, T., Hirose, G., Komatsu, S. et al. Development of anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis during the course of IgA nephropathy: a case report. BMC Nephrol 20, 25 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1207-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1207-3