Abstract

Background

Recurrence of glomerulonephritis is an important risk factor for renal graft dysfunction. Cryoglobulinemia is known as a relatively rare cause of renal failure, and doctors are usually hesitant to perform transplantation on a recipient with cryoglobulinemia because of the risk for graft loss. We present a case of renal transplantation on a patient with organ manifestations of type II cryoglobulinemia.

Case presentation

At the age of 44 years, the patient developed acute kidney injury and purpura on the lower extremities with type II cryoglobulinemia after interferon therapy for hepatitis C virus. Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis was suspected; however, despite immunosuppressive therapy combined with plasmapheresis, she eventually needed hemodialysis treatment. She was referred to us at the age of 49 years for renal transplantation. Cryocrit was 14% and the organ manifestations persisted, including the lower extremity purpura and neurologic symptoms. After monitoring and confirming sufficient suppression of cryoglobulin concentration by immunosuppressive treatment with prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab combined with plasmapheresis, the operation was performed. After transplantation, the cryoglobulin concentration was continuously monitored, and plasmapheresis and rituximab infusion were performed as appropriate. Her graft function has remained stable for 2 years and 6 months.

Conclusion

Our case suggested that a patient with cryoglobulinemia and persistent organ manifestations can receive a renal graft if the cryoglobulin concentration is sufficiently controlled by pretransplant treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

One important risk factor for renal graft dysfunction is de novo and recurrent glomerulonephritis, although rejection and infection are more common [1, 2]. Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate in a cold environment, can produce systemic organ damage [3, 4], and are known as a relatively rare cause of renal failure. Previous case reports have shown the recurrence of cryoglobulinemia in a renal allograft in patients who received a kidney transplant [3, 5, 6]. Those past experiences may cause doctors to hesitate to perform transplantation. We present a case of renal transplantation on a patient with organ manifestations of type II cryoglobulinemia. Good graft function was maintained for 2 years and 6 months after strict management of the cryoglobulin concentration by immunosuppressive therapy combined with plasmapheresis from the pretranplant period.

Case presentation

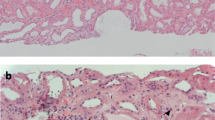

The patient was a 49-year-old woman who was diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) serotype 2 infection at the age of 29 years during pregnancy with her first child. She received interferon therapy, which afforded sustained virologic response. At the age of 41 years, she was diagnosed with macroglobulinemia based on a high serum IgM (2732 mg/dL) with M-protein of IgM-kappa by immunoelectrophoresis and the normal number of plasma cells in the bone marrow. She was asymptomatic and was followed-up without medication. At the age of 44 years, she developed acute kidney injury and purpura on the bilateral lower extremities with type II cryoglobulinemia, which was composed of monoclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG. Skin biopsy of the purpuric lesion revealed inflammatory infiltrates and small vessels with hyaline thrombi (Fig. 1).

Renal biopsy was avoided because of severe hypertension and thrombocytopenia, but cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis was strongly suspected. She received plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy with rituximab (RIT), cyclophosphamide (CPA), and glucocorticoid, but eventually needed hemodialysis treatment within the same year. The purpura of the extremities and neuropathy did not improve and she kept receiving double filtration plasmapheresis (DFPP) biweekly for cryoglobulin depletion. She requested living renal transplantation and was referred to us.

On our initial examination, livedo reticularis, hypothermoesthesia, and hypoalgesia on the bilateral lower extremities were observed (Fig. 2). Laboratory studies indicated white blood cell count 5300/μL, hemoglobin 10.6 g/L, platelet count 21.0 × 104/μL, serum creatinine (Cr) 5.42 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein 0.47 mg/dL. IgG, IgA, and IgM were 1128.9 mg/dL, 211.8 mg/dL, and 371.1 mg/dL, respectively. Complement C3 was 79.0 mg/dL (normal range: 60–120 mg/dL), CH50 was 18.9 U/mL (normal range: 30–40 mg/dL), and rheumatoid factor (RF) was 2213.5 IU/mL. Although the recipient was negative for HCV-RNA on TaqMan quantitative assay, cryocrit was 14% and type II cryoglobulinemia was still demonstrated. As measured in our laboratory, the IgG and IgM concentrations within the cryoprecipitate (cryo-IgG and cryo-IgM) were 360.3 mg/dL and 261.3 mg/dL, respectively. An appropriate technique was necessary to get the correct value of cryoglobulin concentration, which can easily fluctuate and cause a reading error [7]. Blood samples were collected in pre-warmed syringes and tubes, clotted for 20 min, and centrifuged at 37 °C for 5 min; 1 mL of supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C for 3 days. Then, the precipitate was dissolved in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline, and globulin concentration was measured. We routinely took an average of 2 or more measurements.

Because cryoprotein concentration was reported to correlate with the severity of symptoms and useful in monitoring response to treatment [4], living renal transplantation was planned when the concentration was suppressed enough by pretransplant treatment. The pretransplant clinical course is shown in Fig. 3. Prednisolone (PSL), CPA, and RIT were started 50 days before the transplantation, and DFPP and splenectomy were combined. Immediately before the operation, cryo-IgG and cryo-IgM were sufficiently suppressed and cryocrit was 0%.

The donor was her 70-year-old mother, whose left kidney was transplanted to the recipient’s right iliac fossa. During the operation, hypothermia was prevented by placing the recipient in a warm operating room and by giving warm fluid replacement and heating blankets.

Basiliximab, PSL, CPA, and cyclosporin were used for posttransplant immunosuppression, and CPA was changed to mycophenolate mofetil 1 month after the operation (Fig. 4). The cryoglobulin concentration and the CD20-positive cell counts were monitored, and DFPP and RIT infusion were performed as appropriate. She remained stable with good graft function and improved purpura and neuropathy for 2 years and 6 months, without signs of recurrence.

Discussion

Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that reversibly precipitate in a cold environment; 3 basic types are recognized according to the clonality [8]. Type II is predominantly associated with HCV, which interacts with the major extracellular loop of tetraspanin CD81 on lymphocytes and triggers chronic B cell stimulation [3, 9, 10]. Relapse of vasculitis despite sustained virological response had been reported in 1/3 of cases [11], suggesting that B cell proliferation can become independent of HCV over time. In our case, such B cell clones were suspected to exist.

Cryoglobulinemia is not rare in kidney transplant patients, particularly in patients with chronic HCV infection. Its prevalence was reported to be high, ranging from 37.8 to 81.2% [12,13,14], but in most cases, its concentration is relatively low. Moreover, the reported cryocrit was less than 1% in 92.9% of patients [12].

In our case, the risk of recurrence could not be ignored because of the high amount of cryoglobulins, with skin and neurologic involvement. There were few reports on renal transplantation in patients with cryoglobulinemic disease or with newly developed cryoglobulinemic disease after transplantation [5, 15,16,17,18,19,20]. In most cases, recurrence occurred at the early stage (i.e., within one year) after transplantation and graft loss could not be prevented once it developed (Table 1). Recently, some reports have shown the efficacy of RIT combined with plasmapheresis, but the cases in previous reports were asymptomatic and untreated before the recurrence. Our case was unique in that we attempted renal transplantation in a recipient with active manifestations of cryoglobulinemia but who was treated prophylactically. The overall outlook of cryoglobulinemia was reported to be poor in patients with high cryocrit, low C3 values, high creatinine at diagnosis, alveolar haemorrhage, or intestinal ischemia [3]. However, there is no study that determined the risk factors for recurrence after transplantation. Other reports showed that some signs, such as hypocomplementemia or elevated RF, can lead to recurrence [3, 19]. Those past experiences showed that the risk of transplantation was relatively high in cases with important organ complications, such as lung and intestinal involvement, low complement values, or poor control of cryocrit.

Our case report had some limitations. First, errors in the measurement of cryoglobulin can easily occur [7]. Although we paid enough attention and routinely took an average of 2 or more measurements, errors were still possible. Furthermore, other than our therapy adjustment, various factors may have contributed to the cryoglobulin concentrations and include general infection, use of other drugs, or influenza vaccination [3]. In our clinical course, the cryocrit values did not clearly respond to the treatment and were not perfectly correlated with the cry-IgM concentrations. Second, although high cryocrit values were reported to be an important risk factor for cryoglobulinemia recurrence [3], managing the cryocrit alone may not be enough. Third, graft biopsy was not performed because the patient was on anticoagulant to prevent cryoglobulinemia-related thrombus and the intestinal tract was located anterior to the transplanted kidney. Going forward, histological changes on biopsy samples need to be confirmed.

As of this writing, her graft function has remained stable for 2 years and 6 months. Our case suggested that a patient with cryoglobulinemia, even with the persistence of organ manifestations, can receive a renal graft when its concentration is sufficiently controlled by pretransplant treatment.

Abbreviations

- CPA:

-

Cyclophosphamide

- DFPP:

-

Double filtration plasmapheresis

- DSA:

-

Donor-specific antibody

- MMF:

-

Mycophenolate mofetil

- PSL:

-

Prednisolone

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- RIT:

-

Rituximab

References

Golgert WA, Appel GB, Hariharan S. Recurrent glomerulonephritis after renal transplantation: an unsolved problem. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:800–7.

Morozumi K, Takeda A, Otsuka Y, Horike K, Gotoh N, Watarai Y. Recurrent glomerular disease after kidney transplantation: an update of selected areas and the impact of protocol biopsy. Nephrology (Carlton). 2014;19(Suppl 3):6–10.

Ramos-Casals M, Stone JH, Cid MC, Bosch X. The cryoglobulinaemias. Lancet. 2012;379:348–60.

Damoiseaux J. The diagnosis and classification of the cryoglobulinemic syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;13:359–62.

Hiesse C, Bastuji-Garin S, Santelli G, Moulin B, Cantarovich M, Lantz O, Charpentier B, Fries D. Recurrent essential mixed cryoglobulinemia in renal allografts. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol. 1989;9:150–4.

Basse G, Ribes D, Kamar N, Esposito L, Rostaing L. Life-threatening infections following rituximab therapy in renal transplant patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Clin Nephrol. 2006;66(5):395–6.

Bakker AJ, Slomp J, de Vries T, Boymans DA, Veldhuis B, Halma K, Joosten P. Adequate sampling in cryoglobulinaemia: recommended warmly. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:85–9.

Brouet JC, Clauvel JP, Danon F, Klein M, Seligmann M. Biologic and clinical significance of cryoglobulins. A report of 86 cases. Am J Med. 1974;57:775–88.

Rosa D, Saletti G, De Gregorio E, Zorat F, Comar C, D'Oro U, Nuti S, Houghton M, Barnaba V, Pozzato G, Abrignani S. Activation of naïve B lymphocytes via CD81, a pathogenetic mechanism for hepatitis C virus-associated B lymphocyte disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18544–9.

Knight GB, Gao L, Gragnani L, Elfahal MM, De Rosa FG, Gordon FD, Agnello V. Detection of WA B cells in hepatitis C virus infection: a potential prognostic marker for cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and B cell malignancies. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2152–9.

Landau DA, Saadoun D, Halfon P, Martinot-Peignoux M, Marcellin P, Fois E, Cacoub P. Relapse of hepatitis C virus-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia vasculitis in patients with sustained viral response. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:604–11.

Wu MJ, Lan JL, Shu KH, Cheng CH, Chen CH, Lian JD. Prevalence of subclinical cryoglobulinemia in maintenance hemodialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:52–7.

Sens YA, Malafronte P, Souza JF, Bruno S, Gonzalez RB, Miorin LA, Jabur P, Forte WC. Cryoglobulinemia in kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:4273–5.

Faguer S, Kamar N, Boulestin A, Esposito L, Durand D, Blancher A, Rostaing L. Prevalence of cryoglobulinemia and autoimmunity markers in renal-transplant patients. Clin Nephrol. 2008;69:239–43.

Tarantino A, Moroni G, Banfi G, Manzoni C, Segagni S, Ponticelli C. Renal replacement therapy in cryoglobulinaemic nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9:1426–30.

Brunkhorst R, Kliem V, Koch KM. Recurrence of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis after renal transplantation in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. Nephron. 1996;72:465–7.

Basse G, Ribes D, Kamar N, Mehrenberger M, Esposito L, Guitard J, Lavayssière L, Oksman F, Durand D, Rostaing L. Rituximab therapy for de novo mixed cryoglobulinemia in renal transplant patients. Transplantation. 2005;80:1560–4.

Basse G, Ribes D, Kamar N, Mehrenberger M, Sallusto F, Esposito L, Guitard J, Lavayssière L, Oksman F, Durand D, Rostaing L. Rituximab therapy for mixed cryoglobulinemia in seven renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2308–10.

Takeda A, Ootsuka Y, Suzuki T, Yamauchi Y, Tsujita M, Kawaguchi T, Horike K, Oikawa T, Goto N, Nagasaka T, Watarai Y, Uchida K, Morozumi K. A case report of recurrence of mixed cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis in a renal transplant recipient. Clin Transpl. 2010;24(Suppl 22):44–7.

Sforza D, Iaria G, Tariciotti L, Manuelli M, Anselmo A, Ciano P, Manzia TM, Toti L, Tisone G. Deep vein thrombosis as debut of cytomegalovirus infection associated with type II cryoglobulinemia, with antierythrocyte specificity in a kidney transplant recipient: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2782–4.

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting our findings are contained within the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK wrote the manuscript. TK, HN, and KI were the treating physicians of the patient. HN and KI corrected and analyzed the data and helped in creating the figs. SB and YI interpreted the data and helped in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kasagi, T., Nobata, H., Ikeda, K. et al. Successful renal transplantation to a recipient with type II cryoglobulinemia: a case report. BMC Nephrol 19, 170 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-018-0966-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-018-0966-6