Abstract

Background

Mycetoma is a chronic granulomatous subcutaneous infection caused by anaerobic pseudofilamentous bacteria or fungi. It is commonly prevalent in tropical and subtropical countries. Men are more susceptible to the disease due to greater participation in agricultural works. Mycetoma commonly involves lower extremities, wherein untreated cases lead to aggressive therapeutic choices, such as amputation of the affected body organs and consequently lifelong disability.

Case presentation

In this report, we present the rare case of a 58-year-old man, originally from Algeria with a left foot chronic tumefaction of 5 years. In the initial clinical examination, mycetoma was diagnosed based on tumefaction and the presence of multiple sinuses with the emission of white grains. The latter was observed via direct examination. The histopathological analysis demonstrated an actinomycetoma caused by bacteria, as the etiological agent. Imaging showed a bone involvement with osteolysis at the levels of 2nd to 4th metatarsal diaphysis. The mycological and bacterial cultures were both negative. For an accurate diagnosis, the obtained grains were subjected to molecular analysis, targeting the 16S-rDNA gene. Molecular identification yielded Actinomadura madurae as the causal agent, and 800/160 mg of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was prescribed twice a day for 1 year, as a treatment.

Conclusion

Considering low information about this disease, especially in non-endemic areas, it is of high importance to enhance the knowledge and awareness of clinicians and healthcare providers, in particular in the countries with immigration issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mycetoma is a chronic subcutaneous tissue infection caused by anaerobic pseudofilamentous bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). It is commonly observed in tropical and subtropical regions in a zone, known as the “Mycetoma belt” with dry and arid climates. India, Sudan, Somalia, Senegal, Yemen, Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, and Argentina bear the most cases of disease burden [1]. The cases outside this zone are uncommon and usually imported by immigrants. Despite multiple cases reported worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of the disease remain underestimated [2]. Mycetoma is more prevalent in people between 20 and 40 years old, with a low socioeconomic level, and is more common in men rather than women (3:1) [3]. Mycetoma occurs mostly in the lower extremities of the body, particularly in the feet but other parts of the body can also be involved [4]. Although mycetoma is mostly a painless infection leading to delayed medical consultation, it can be painful in case of secondary bacterial infection [5, 6]. It is usually characterized by single or multi-fistulized pseudotumor and the emission of grains. The grains can vary in size, color, and consistency, depending on the etiological species [3].

Considering almost similar clinical manifestations appearing in actinomycetoma and eumycetoma and the differences in their treatments, accurate identification of causal microorganisms is crucial [7]. Furthermore, due to significant clinical presentations and complexity in therapeutic implications, the disease diagnosis in the early stages is of high importance. Delay in diagnosis may lead to the aggressive therapeutic selections, like amputation of affected body members, and consequently lifelong disability [8]. The diagnosis is mainly based on clinical characteristics and microbiological identification of the causative agent [3].

Case presentation

A 58-year-old man with a chronic tumefaction of the left foot was referred due to suspicion of mycetoma. The patient was a restaurant-worker, originally from Algeria who was inhabited in France since 2001, with regular travel to his homeland but not to the known classical endemic areas. According to the patient, he was living in a rural region in Kabylie (north-east of Algeria) and suffered from left foot tumefaction for 5 years. He was initially hospitalized in 2017, in a health center in Paris. The initial medical check-up was performed including imaging, microbiological and histopathological examinations. The clinical diagnosis was made by a classical triad of tumefaction (32 cm perimeter of left foot comparing to 26 cm for right foot), presence of multiple sinuses, and emission of white grains. Staphylococcus aureus, and an anaerobic Gram-positive bacillus-like bacterium similar to Actinomyces sp., were identified, using classical microbiological culture with no species-specific identification. Significant infiltration of periosseous soft tissues and an osteolytic aspect of 2nd and 4th metatarsal with multiple geodes were observed by radiology and MRI. Echography did not reveal superficial thrombophlebitis in association with this tumefaction. Therapy was initialized, using amoxicillin (6 g/day for 4 months) as the first-line therapeutic choice during initial hospitalization, in 2017. Due to no favorable evolution, his treatment was left incomplete.

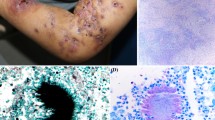

Eighteen months later, the patient was referred with the same problem to Avicenne Hospital (Bobigny, France), for accurate identification of causative agent(s) and re-initiating an adapted treatment. Clinical diagnosis revealed 3 cm enlargement in tumefaction circumference, presence of 11 sinuses in plantar, 10 sinuses on the topside of the foot, and emission of white grains (Fig. 1). Direct microscopic examination of crushed grains showed neither mycelial nor actinomycete filaments. A deep tissue biopsy was performed for histopathological examination and the sinuses secretions including the grains were used for microbiological cultures and molecular analysis. The histopathological assessment showed pseudofilamentous Gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 2a), necrotic debris, granulomatous and polymorphic inflammatory infiltrates, confirming an actinomycetoma (Fig. 2b). Cultures on Loewenstein-Jensen, Sabouraud-chloramphenicol-gentamycin, and blood agar were negative after 3 months of incubation at 30 °C. The imaging assessments were performed again, confirming the extensive lesions of the initial assessment (Fig. 3).

a Left foot tomodensitometry demonstrating metatarsals osteolysis and thickened soft parts; b Foot X-rays with thickened soft parts of the left foot and the 4th metatarsal osteolysis; c Soft tissue infiltration by bacteria and bone involvement of the left foot demonstrated using T2 sequence fat-sat pulses in MRI

Bacterial DNA in the grains isolated from the patient was extracted using bio-robot EZ1 and then subjected to a conventional PCR, targeting the 16S-rDNA gene with fD1 (fwd: AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and rp2 (rvs: ACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT) primers [9]. Obtained bilateral sequences were edited, aligned using BLAST, and identified as Actinomadura madurae, based on ≥99% identity with GenBank sequence (NR026343) and then deposited in GenBank with accession number NZ148818. In order to evaluate intraspecific variability, phylogenetic relationships, and polymorphisms within Actinomadura species, an inferred phylogenetic tree of A. madurae (identified in this study) together with GenBank sequences, was constructed based on the Neighbor-Joining method with bootstrap values, determined by 1000 replicates. This tree showed high congruence with the 16S-rDNA tree, since all taxa were concordantly clustered into the same species’ group (Fig. 4).

For treatment, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (800/160 mg) was prescribed twice a day for 3 months with an expected duration of 1 year. Complete Blood Count (CBC) was routinely verified to ensure no overdose toxicity. Three months later, 2 cm reduction in left foot circumference was observed. Consequently, the treatment was continued until complete healing.

Discussion and conclusions

Little is known about the mycetoma in Algeria. Actinomadura madurae was first described in 1894 by Vincent, as Streptothrix maduruae, based on several strains isolated from an Algerian case of Madura foot [10]. Afterward, other primitive cases of mycetoma caused by A. madurae were documented over 80 years ago [11, 12]. A case of mycetoma caused by Streptomyces somaliensis was later reported from the southern region of Atlas Mountain [13]. According to a retrospective investigation carried out from 1995 to 2005, 13 mycetoma cases were documented, from which five cases were actinomycetomas (caused by A. madurae, S. somaliensis, and Nocardia asteroïdes), three eumycetomas (caused by Madurella mycetomatis) and three without etiologic agent identification [14]. Diversity in causative agents of mycetoma in Algeria is geographic-dependent [14]. In the north, the humidity seems to be suitable for species such as N. asteroïdes and M. mycetomatis, while the southern arid/desert regions are favorable for the development of species such as S. somaliensis [14]. Although Actinomadura species is known as an agent of desert areas [15], we isolated it from a patient, originally from a humid region (880 mm rainfall), which supports the findings reported by Zait et al. [14]. Contrary to the little information found about the human actinomycetoma, the search for actinomycetes in the environment (water and soils) was performed in several parts of Algeria, in particular in the south and north-eastern regions, allowing to isolate several genera such as Actinomadura, Saccharothrix, and Streptomyces [16,17,18,19]. Imported cases of actinomycetoma have been already reported in European countries such as Italy [20], France [21] and Switzerland [22]. Nevertheless, some reports of autochthonous cases from Italy [23] and France [24] have been also documented, suggesting the local occurrence of actinomycetoma in Europe.

Diagnosis of the mycetoma and identification of etiological agents is a challenging issue, especially in non-endemic areas. Microbiological culture and histopathological analysis are the diagnostic tools used for the identification of causal agent(s) [7] but they possess some drawbacks, including failure in culture, difficulties in the direct examination or invasive biopsy [25]. Molecular analysis of bacterial species isolated from our patient revealed A. madurae as the etiologic agent with ≥99% identity with GenBank sequences. Therefore, molecular analysis can be considered as a reliable tool, asserting accurate identification of causal agents [26]. Regarding the increasing number of refugees coming from endemic areas to Europe, the knowledge improvement of the clinicians on mycetoma is essential, particularly in those regions with increasing immigration issues. Moreover, there is a lack of knowledge concerning the impact of climate change on the worldwide prevalence of mycetoma.

This case highlights the importance of early diagnosis and accurate identification of the causative organisms of mycetoma, which allows effective antibiotic therapy. Due to no improvement of our patient with amoxicillin as a first-line treatment, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was prescribed, which led to an improvement in 3 months [27]. The latter is considered as the gold standard for actinomyces treatment, particularly in cases of bone invasion.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Fahal AH. Mycetoma: a thorn in the flesh. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:3–11.

van de Sande WWJ. Global burden of human Mycetoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2550.

Reis CMS, Reis-Filho EGM. Mycetomas: an epidemiological, etiological, clinical, laboratory and therapeutic review. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:8–18.

Alam K, Maheshwari V, Bhargava S, Jain A, Fatima U, Haq E. Histological diagnosis of Madura foot (Mycetoma): a must for definitive treatment. J Global Infect Dis. 2009;1:64–7.

Ahmed AOA, Abugroun EAM. Unexpected high prevalence of secondary bacterial infection in patients with Mycetoma. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:850–1.

Fahal A, Mahgoub ES, Hassan AME, Abdel-Rahman ME. Mycetoma in the Sudan: An Update from the Mycetoma Research Centre, University of Khartoum, Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003679.

Ahmed AA, van de Sande W, Fahal AH. Mycetoma laboratory diagnosis: review article. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005638.

Belkum A, Fahal A, Sande WWJ. Mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis: a completely neglected medico-social dilemma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;764:179–89.

Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703.

Vincent H. Etude sur le parasite du pied le Madura. Ann Inst Pasteur. 1894;129:8.

Catanei A. Étude parasitologique de trois nouveaux cas de mycétome du pied observés en Algérie en 1933. Arch Inst Pasteur Alger. 1934;12.

Gatmel A, Grocdemange L, Legroux CH. Sur un cas de mycétome observé en Algérie. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1927;20:11–3.

Destombes P, Rannou M, Nell R. Mycetoma due to Streptomyces somaliensis seen in Algeria in the south area of the atlas mountains. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1965;58:1017–20.

Zait H, Madani K, Abed-Benamara M, et al. Mycetoma in Algeria. About two new cases. Review of cases reported between 1995 and 2005. J Mycol Méd. 2008;18:116–22.

Bonnet E, Flecher X, Paratte S, et al. Actinomadura meyerae osteitis following wound contamination with hay in a woman in France: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:32.

Boudemagh A, Kitouni M, Boughachiche F, et al. Isolation and molecular identification of actinomycete microflora, of some saharian soils of south East Algeria (Biskra, EL-Oued and Ourgla) study of antifungal activity of isolated strains. J Mycol Med. 2005;15:39–44.

Kitouni M, Boudemagh A, Oulmi L, et al. Isolement d’actinomycètes producteurs de substances bioactives à partir d’échantillons d’eau, de sol et d’écorces d’arbres du nord-est de l’Algérie. J Mycol Med. 2005;15:45–51.

Badji B, Zitouni A, Mathieu F, Lebrihi A, Sabaou N. Antimicrobial compounds produced by Actinomadurasp. AC104, isolated from an Algerian Saharan soil. Can J Microbiol. 2006;52:373–82.

Boubetra D, Zitouni A, Bouras N, Mathieu F, Lebrihi A, Schumann P, Spröer C, Klenk HP, Sabaou N. Saccharothrix saharensis sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from Algerian Saharan soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:3744–9.

Fasciana T, Colomba C, Cervo A, et al. Madura foot: an imported case of a non-common diagnosis. Infez Med. 2018;2:167–70.

Mattioni S, Develoux M, Brun S, et al. Management of mycetomas in France. Med Mal Infect. 2013;43:286–94.

Mekoguem C, Triboulet C, Gouveia A. Madurella mycetomatis infection of the buttock in an Eritrean refugee in Switzerland: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13:32.

Mencarini J, Antonelli A, Scoccianti G, et al. Madura foot in Europe: diagnosis of an autochthonous case by molecular approach and review of the literature. New Microbiol. 2016;39:156–9.

Gilquin JM, Riviere B, Jurado V, et al. First case of Actinomycetoma in France due to a novel Nocardia species, Nocardia boironii sp nov. mSphere. 2016;1:e00309–16.

Siddig EE, Mhmoud NA, Bakhiet SM, Abdallah OB, Mekki SO, El Dawi NI, et al. The accuracy of Histopathological and Cytopathological techniques in the identification of the Mycetoma causative agents. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007056.

Salipante SJ, SenGupta DJ, Hoogestraat DR, Cummings LA, Bryant BH, Natividad C, Thielges S, Monsaas PW, Chau M, Barbee LA, Rosenthal C, Cookson BT, Hoffmana NG. Molecular diagnosis of Actinomadura madurae infection by 16S rRNA deep sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:4262–5.

Vera-Cabrera L, Ochoa-Felix EY, Gonzalez G, Tijerina R, Choi SH, Welsh O. In vitro activities of new quinolones and oxazolidinones against Actinomadura madurae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1037–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Valerie Zeller and Dr. Habib Ben Romdhane for their valuable helps concerning preparation of imaging photos.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AI, FC, and MA2; methodology: MA1, MA2, TP, YF, AM, TF, SB; validation: MA2, AI, and FC; writing—original draft preparation: MA2, AI, and FC; writing—review and editing: MA2, FC, and AI. All Authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was granted trough protocol number of 95/99/AVC/ESA by the Avicenne Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

A written consent was provided and signed by the patient including the authorization for publishing the clinical information.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Izri, A., Aljundi, M., Billard-Pomares, T. et al. Molecular identification of Actinomadura madurae isolated from a patient originally from Algeria; observations from a case report. BMC Infect Dis 20, 829 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05552-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05552-z