Abstract

Background

In accordance with international guidance for tuberculosis (TB) prevention, the Tanzanian Ministry of Health recommends isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) for children aged 12 months and older who are living with HIV. Concerns about tolerability, adherence, and potential mistreatment of undiagnosed TB with monotherapy have limited uptake of IPT globally, especially among children, in whom diagnostic confirmation is challenging. We assessed IPT implementation and adherence at a pediatric HIV clinic in Tanzania.

Methods

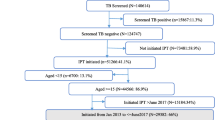

In this prospective cohort study, eligible children living with HIV aged 1–15 years receiving care at the DarDar Pediatric Program in Dar es Salaam who screened negative for TB disease were offered a 6-month regimen of daily isoniazid. Patients could choose to receive IPT via facility- or community-based care. Parents/caregivers and children provided informed consent and verbal assent respectively. Isoniazid was dispensed with the child’s antiretroviral therapy every 1–3 months. IPT adherence and treatment completion was determined by pill counts, appointment attendance, and self-report. Patients underwent TB symptom screening at every visit.

Results

We enrolled 66 children between July and December 2017. No patients/caregivers declined IPT. Most participants were female (n = 43, 65.1%) and the median age was 11 years (interquartile range [IQR] 8, 13). 63 (95.5%) participants chose the facility-based model; due to the small number of participants who chose the community-based model, valid comparisons between the two groups could not be made. Forty-nine participants (74.2%) completed IPT within 10 months. Among the remaining 17, 11 had IPT discontinued by their provider due to adverse drug reactions, 5 lacked documentation of completion, and 1 had unknown outcomes due to missing paperwork. Of those who completed IPT, the average monthly adherence was 98.0%. None of the participants were diagnosed with TB while taking IPT or during a median of 4 months of follow-up.

Conclusions

High adherence and treatment completion rates can be achieved when IPT is integrated into routine, self-selected facility-based pediatric HIV care. Improved record-keeping may yield even higher completion rates. IPT was well tolerated and no cases of TB were detected. IPT for children living with HIV is feasible and should be implemented throughout Tanzania.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) represents an enormous global disease burden, especially for people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1, 2]. Rates of TB disease are particularly high in children living with HIV [3, 4]. Deaths from HIV/TB co-disease can be reduced by preventing or treating latent TB infection [5, 6]. Standard HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) alone is insufficient in preventing pediatric TB in high TB burden countries [7].

Consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended expanded delivery of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) to reach those at greatest risk for progressing to TB disease [3], including children living with HIV. In this population, IPT has been shown to reduce mortality by 50% and incidence by more than 70% in high TB-burden countries [8]. Due to the low likelihood of drug-drug interactions, evidence of effectiveness, and low cost, the WHO recommends that people living with HIV, including children older than 12 months, receive at least 6 months of IPT as part of comprehensive HIV care [9].

Despite international endorsement [10], IPT enrolment and completion has remained low, especially in low-income countries with a high TB burden [11]. In South Africa and Uganda, for example, IPT uptake was found to be as low as 15% even when available [12]. Barriers to uptake include fear of drug resistance, difficulty of screening for TB due to lack of access to TB diagnostic tests, negative or unfriendly interactions between healthcare workers and parents, stigma, and fears of side effects [13,14,15,16,17]. To support IPT rollout, the WHO has created a simplified screening algorithm based on clinical symptoms that increases cost-effectiveness of TB screening [18, 19]. Furthermore, provision of choice of IPT delivery models, such as community-outreach versus facility-based care, combining IPT and ART refills into single visits, and providing flexible appointment schedules have been associated with rates of completion and adherence of over 80% [20,21,22].

Tanzania is one of the 30 high burden countries for TB and TB/HIV co-disease; an estimated 40,000 Tanzanians developed HIV-associated TB in 2018 [23]. While the Ministry of Health in Tanzania has officially recommended IPT for children living with HIV since 2009 [24], implementation is still not the standard of care at many healthcare facilities [25]. This study sought to determine whether patient-selected IPT delivery coordinated with ART delivery would yield high adherence and treatment completion in children living with HIV in Dar es Salaam.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study of patient-selected IPT delivery models at the DarDar Pediatric Program clinic (DPP) in Dar es Salaam. The clinic provides routine outpatient HIV care for children aged 15 and below together with their parents/caretakers who may also be living with HIV. DPP is located in the Dar es Salaam city center and serves a mixed urban and rural population, with a total patient enrollment of approximately 285 children and 162 parents/caretakers.

Enrollment procedures

The DPP clinical staff identified a convenience sample of children living with HIV who were eligible for IPT according to national guidelines during the study enrollment period. Specifically, eligible patients were 1) HIV-infected, 2) between the ages of 1 and 15 years, 3) enrolled in care at DPP, 4) ruled out for TB disease by using the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Program (NTLP) symptom screen tool, 5) without contraindications to IPT as per national guidelines (e.g. severe liver disease or known adverse reaction to isoniazid), and 6) not planning to move outside of Tanzania in the next 6-months. Per NTLP guidance, only children who had signs or symptoms for TB based on the symptom screening tool were required to undergo a chest x-ray and sputum testing. If a child had a negative chest x-ray and sputum testing, they were eligible to participate in the study. Sputum testing involved AFB smear, culture, and Xpert MTB/RIF. The study nurses obtained verbal informed consent in Kiswahili using a standardized form, which included counseling on the risks and benefits of IPT. Informed consent was obtained from parent/caregivers. Children who were able to (typically those over age 5) provided verbal assent to a nurse who used age-adjusted language and questions to gauge the child’s understanding. The parent/caregiver, in conjunction with the child (when they were old enough to participate in the decision-making), then selected their IPT delivery model and were dispensed isoniazid (INH) (dosed at 10-15 mg/kg up to a maximum of 300 mg/day). Most children received a 1- or 2-month supply of INH, based on the timing of their next scheduled appointment for ART.

IPT delivery models

Children (and their parent/caregiver) were offered a choice of either facility- or community-based IPT delivery models. In the facility-based model, TB screening, adherence assessment, and INH refills were coordinated with the child’s routine ART refill appointments at the clinic, typically in monthly or bimonthly intervals. Roundtrip travel to the clinic via public transportation was reimbursed for all children and their parents/caregivers regardless of study involvement. One clinician and two nurses performed the screening, adherence assessment, refills, and follow-up of patients. In the community-based model, nurses performed the same functions in the child’s home and dispensed both their INH and ART refills. Patients could switch models at any time during the study and were reminded of this at each follow-up appointment.

Follow-up visits and monitoring

IPT refill intervals followed the child’s pre-existing ART refill schedule. The study nurses attempted to contact by telephone any study participant who missed an appointment as per routine clinic practice. Adherence was assessed at each visit and IPT completion was documented after the final IPT refill. Average monthly adherence was determined via pill counts. Follow-up visits were attended by the child and parent/caregiver, the child alone, or the parent/caregiver alone. Regardless of who attended the follow-up appointment, INH pill bottles were examined for adherence assessment. INH and ART refills were provided at each follow-up visit. In addition, participants were screened at every appointment for TB disease using the NTLP-recommended symptom screen. If any TB signs or symptoms were present, a chest x-ray and sputum for AFB smear, culture, and Xpert MTB/RIF would be performed. Participants with confirmed TB disease were referred to a separate TB clinic for treatment; if TB was excluded, the child resumed IPT.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was IPT completion, defined as completing a 6-month course of INH within 10 months. When exact treatment completion dates were not documented, the completion date was estimated by adding the days of IPT remaining (as indicated by the number of pills that the patient had remaining) at the time of their last IPT appointment. The secondary outcome was adherence, defined as the percentage of prescribed INH taken. Adherence was measured using a combination of pill counts at follow-up appointments, appointment adherence, and patient self-reporting. Pill counts were obtained at each follow up visit and used to calculate monthly adherence. Appointment adherence was used to supplement pill counts by calculating how many INH pills should be left given the interval between appointments. Rarely, participants provided additional information to explain why the pill count and appointment attendance might not accurately reflect their adherence, such as when they lost or dropped pills, to allow our study team to make corrective calculations to their adherence.

Training and monitoring

One clinic physician and two nurses were trained in IPT administration. The study team conducted staff training through didactic lectures, discussion, and role-play. Training sessions focused on 1) review of the national IPT policy, 2) review of the benefits of IPT, 3) results from the IPT program evaluation, 4) patient motivational interviewing techniques and shared decision-making, 5) overview of the project using the approved standard operating procedures, and 6) transfer of data collection tools.

Data analysis

Study data were collected using standard paper registers. Basic demographics, method of IPT delivery, reasons for choosing that delivery method, pill counts, dates of IPT initiation and refills, adverse reactions, deviations from prescribed treatment, and patient-initiated switches from the initially-selected delivery model were all recorded. Qualitative data notes, such as reason for choosing a delivery model, were documented by the study staff on the register and later categorized as: general preference (reason not specified), confidentiality/stigma concerns, ease, perceived better treatment support, and other. These data were transferred to a password-protected Microsoft Excel 2010 spreadsheet on password-protected study laptops. Data were exported to JMP v13 for final analysis. All data were validated by comparison between paper and electronic entries. Descriptive analyses using means/medians and proportions were conducted for continuous and categorical data respectively. Adherence was calculated at the first follow-up and for all subsequent visits with available data.

The study protocol was approved by the National Institute for Medical Research in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) Institutional Review Board in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; and the Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects in Hanover, NH, USA.

Results

We enrolled 66 eligible children between July and December of 2017, and the last child finished IPT in July 2018. Although not formally documented, the clinic nurses reported that out of the 66 children approached, all accepted IPT. Most participants were female (n = 43, 65.1%) and all were on ART. The median age was 11 years (interquartile range [IQR] 8–13). Most children did not have a history of TB (n = 54, 81.8%) and 33 (50.0%) were at WHO clinical stage III for HIV at initiation. Detailed participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

The facility-based model was selected by 63 (95.5%) participants at IPT initiation. (Table 2). Most cited confidentiality concerns (n = 30, 45.5%) as their main reason for choosing the facility-based model, specifically because they feared that the community-based model would inadvertently disclose their HIV status to their neighbors. Other reasons for choosing the facility-based model included ease (n = 9, 13.6%) as visits to the facility for HIV-related care were already integrated into their routine, and a general preference to maintain their routine (n = 18, 27.2%). Most participants (n = 61, 92.4%) retained their initially chosen model throughout the study. Of the 5 participants who switched models, 3 (60%) switched once after the first IPT visit, and 2 (40%) switched multiple times throughout the study. Of the 5 participants who switched their models (either once or many times), 3 (60.0%) initiated the study by selecting the facility-based model and 2 (40.0%) initiated with the community-outreach model.

Adherence and treatment outcomes

Forty-nine (74.2%) participants were confirmed to have completed IPT. Of those that completed IPT, pill count data showed a 98% average monthly adherence. Only one child had an adherence of less than 70%, and 33 (50%) had adherence rates between 93 and 100%. The recorded monthly adherence of 98% is well above the 80% standard threshold for adherence. The estimated mean time to complete IPT was 27.6 weeks (6.4 months) among the 35 participants for whom a precise completion date could be determined. Incomplete record keeping meant that not all participants had an exact date of IPT completion. All participants who completed their IPT did so within 10 months of initiation, and no participants missed more than 90 days of IPT doses. Data on IPT adherence and treatment completion are shown in Table 3.

Among the 17 (25.8%) children who were not included in the adherence analysis, 5 (29.4%) were lacking IPT completion documentation in their medical records, 11 (64.7%) discontinued treatment, and 1 (5.9%) had an unknown outcome due to missing paperwork. Inconsistent documentation practices and patients forgetting to bring their pill bottles for adherence review (pill counts) resulted in incomplete IPT documentation that prevented adherence determinations in some cases. Among the 11 participants who discontinued IPT, 7 (63.6%) did so at the recommendation of the physician due to one or more adverse reactions including joint pain (n = 2), vomiting (n = 2), numbness (n = 3), oral ulcers (n = 1) and rashes (n = 1). No cases of TB were suspected or confirmed among participants while on IPT or during a median of four additional months of follow up.

Discussion

Our study findings demonstrate that high rates of IPT adherence and treatment completion are achievable in a pediatric HIV clinic population through IPT delivery coordinated with ART refills. While too few patients selected the community-based model of delivery to compare the effectiveness of the two models, the overall model of self-selected IPT delivery led to high adherence across the entire study cohort. Integrated care, achieved by pairing IPT with ART refills, meant that no additional medical visits were necessary and subsequently no additional burden was incurred for the child and their family. Maintaining routine care patterns likely contributed to the high adherence outcomes, as many patients cited this as a reason for choosing their delivery model. Of the six children who were not included in adherence analysis, 5 (83.3%) are believed by the clinic staff who administer their HIV care to have completed IPT but simply lacked official documentation. Among these 5, the mean estimated IPT completion date was 6.5 months after initiation. Thus, it is likely that these five children completed their IPT within the 10-month limit, even if their files did not specify an end date. Using these estimated completion dates, a total of 81.8% (54/66) completed their IPT within the specified timeframe.

Where data were available, adherence was very high (98% monthly average). The fact that this study examined an “ART-established” cohort of participants (with all but one participant having initiated ART > 1 year before IPT initiation) likely contributed to the excellent adherence as participants were habituated to taking daily medication. Our study parallels other similar findings in IPT adherence. Previous studies have found high adherence to IPT amongst pediatric populations living with HIV, suggesting that IPT is a feasible intervention for wider implementation [21, 26]. This study contributes to the adherence literature by examining IPT delivery models within Tanzania. Shared decision making and a patient-centered approach to care has been shown to improve child/patient satisfaction with their healthcare and increase medication adherence [27]. Furthermore, the WHO’s “Framework on integrated, people-centred health services” recommends the implementation of five strategies to improve equitable access to care: (1) empowering and engaging people and communities, (2) strengthening governance and accountability, (3) reorienting the model of care, (4) coordinating services within and across sectors, and (5) creating an enabling environment [28]. Our findings align with this framework by engaging individuals and families as active participants in their care, creating an equal and reciprocal relationship between clinical professionals and individuals, and individualizing self-management and treatment plans [28].

Concerns regarding breakthrough TB disease in the pediatric population were not borne out in this study. There were no cases of breakthrough TB and no presentations that warranted further evaluation with bacteriological investigation. The lack of breakthrough TB supports the use of the NTLP-recommended symptom screen to determine patient eligibility for IPT. INH was well tolerated by the majority of the study population. 16.7% (n = 11) of children stopped IPT, primarily due to minor adverse reaction. Shorter regimens to treat latent TB infection have been shown to be as effective as IPT, with high adherence, and potentially better tolerability, including 3 months of daily INH and rifampin, 3 months once-weekly INH and rifapentine, and 4 months of daily rifampin [29, 30]. Future studies should apply the patient-centered delivery choice in this study to these additional regimens.

Our study had three main limitations. First, data on adherence were limited due to incomplete data capture of pill counts by nurses and inconsistent presentation of pill bottles by participants at every appointment (to enable accurate adherence calculations). Similar difficulties in record keeping for IPT delivery have been documented in other similar studies in the region [31]. Nonetheless, while pill count data were incomplete for individual patients, the aggregate data indicate that IPT adherence was consistently high in this pediatric population. Furthermore, a recently published study by Martelli et al. (2019) [32] on pediatric ART adherence in Tanzania found that there was a large lack of agreement between pill count/observed adherence data and adherence data derived from the patient’s viral load (39.9%), suggesting that pill counts may not be an accurate indicator of adherence. Other methods of adherence should be considered for future studies, such as urine analysis to assess INH metabolites, to provide additional objective adherence data [33]. Second, because medication could be dispensed to the child or the parent/caregiver, sometimes the child was not present at follow-up visits. While the study team did not capture the rate at which parents/caregivers attended the appointment alone, this was uncommon. A flexible follow up and INH refill model may have increased appointment adherence as it allowed for pills to be counted and refills to be dispensed even if either the child or the parent/caregiver could not attend; however, this flexibility meant information on TB symptoms and adverse reactions could be provided secondhand by the parent/caregiver, potentially compromising accuracy. Third, the size of the cohort was relatively small. Such a small sample size may have limitations in the scalability of the study’s findings. Further studies with larger cohorts would increase the generalizability of our findings.

Our study demonstrates that high adherence and treatment completion rates can be achieved when IPT is integrated into pediatric HIV care and when patients and their parent/caregiver are involved in choosing delivery methods that best fit their needs. Improved record-keeping and patient pill bottle presentation at appointments may yield even higher completion rates. There were no detected cases of TB. For children living with HIV, IPT can be implemented effectively and should be recommended throughout Tanzania.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates IPT feasibility and high completion rates among children living with HIV in Tanzania. When flexible delivery models and shared decision making are included in standard care, high adherence and treatment completion rates of IPT can be achieved. Coordinating IPT and ART is an effective way to minimize patient visit burden and streamline care delivery. There were no cases of TB were detected during or after the study. Improved record-keeping may yield even higher completion rates. IPT should be implemented into routine pediatric HIV within Tanzania.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

20 October 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral Therapy

- INH:

-

Isoniazid

- IPT:

-

Isoniazid Preventive Therapy

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Gunda DW, Maganga SC, Nkandala I, Kilonzo SB, Mpondo BC, Shao ER, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of active TB among adult HIV patients receiving ART in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2018;2018:1–7.

Liu E, Makubi A, Drain P, Spiegelman D, Sando D, Li N, et al. Tuberculosis incidence rate and risk factors among HIV-infected adults with access to antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2015;29:1391–9.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for Intensified Tuberculosis Case-Finding and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy for People Living with HIV in Resource-Constrained Settings. 2011.

Newton SM, Brent AJ, Anderson S, Whittaker E, Kampmann B. Paediatric tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:498–510.

Chee CB, Sester M, Zhang W, Lange C. Diagnosis and treatment of latent infection with mycobacterium tuberculosis. Respirology. 2013;18:205–16.

Kabali C, Reyn CV, Brooks D, Waddell R, Mtei L, Bakari M, et al. Completion of isoniazid preventive therapy and survival in HIV-infected, TST-positive adults in Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1515–22.

Crook AM, Turkova A, Musiime V, Bwakura-Dangarembizi M, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Nahirya-Ntege P, et al. Tuberculosis incidence is high in HIV-infected African children but is reduced by co-trimoxazole and time on antiretroviral therapy. BMC Med. 2016;14:50.

Zar HJ, Cotton MF, Strauss S, Karpakis JS, Hussey G, Schaaf HS, et al. Effect of isoniazid prophylaxis on mortality and incidence of tuberculosis in children with HIV: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2007;334:136.

The Three I's for TB/HIV: Isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT). World Health Organization 2014;Available from: https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/tb/3is_ipt/en/ [cited 2019 Aug 5].

Frigati LJ, Kranzer K, Cotton MF, Schaaf HS, Lombard CJ, Zar HJ. The impact of isoniazid preventive therapy and antiretroviral therapy on tuberculosis in children infected with HIV in a high tuberculosis incidence setting. Thorax. 2011;66:496–501.

Thindwa D, Macpherson P, Choko AT, Khundi M, Sambakunsi R, Ngwira LG, et al. Completion of isoniazid preventive therapy among human immunodeficiency virus positive adults in urban Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22:273–9.

Shapiro AE, van Heerden A, Schaafsma TT, Hughes JP, Baeten JM, van Rooyen H, et al. Completion of the tuberculosis care cascade in a community-based HIV linkage-to-care study in South Africa and Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21.

Birungi FM, Graham S, Uwimana J, Van Wyk B. Assessment of the isoniazid preventive therapy uptake and associated characteristics: a cross-sectional study. Tuberc Res Treat. 2018;2018:1–9.

Lester R, Hamilton R, Charalambous S, Dwadwa T, Chandler C, Churchyard GJ, et al. Barriers to implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy in HIV clinics: a qualitative study. Aids. 2010;24:S45–8.

Moolphate S, Lawpoolsri S, Pungrassami P, Sanguanwongse N, Yamada N, Kaewkungwal J. Barriers to and motivations for the implementation of a treatment Programme for latent tuberculosis infection using isoniazid for people living with HIV, in upper northern Thailand. Global J Health Sci. 2013;5:60–70.

Costenaro P, Massavon W, Lundin R, Nabachwa SM, Fregonese F, Morelli E, et al. Implementation of the WHO 2011 recommendations for isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) in children living with HIV/AIDS. JAIDS. 2016;71:e1–8.

Teklay G, Teklu T, Legesse B, Tedla K, Klinkenberg E. Barriers in the implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in northern Ethiopia: a mixed quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:840.

Shayo GA, Chitama D, Moshiro C, Aboud S, Bakari M, Mugusi F. Cost-effectiveness of isoniazid preventive therapy among HIV-infected patients clinically screened for latent tuberculosis infection in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:35.

Carmone A, Rodriguez CA, Frank TD, Kiromat M, Bongi PW, Kuno RG, et al. Increasing isoniazid preventive therapy uptake in an HIV program in rural Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action. 2017;7:193–8.

Adams LV, Mahlalela N, Talbot EA, Pasipamire M, Ginindza S, Calnan M, et al. High completion rates of isoniazid preventive therapy among persons living with HIV in Swaziland. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21:1127–32.

Gray DM, Workman LJ, Lombard CJ, Jennings T, Innes S, Grobbelaar CJ, et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy in HIV-infected children on antiretroviral therapy: a pilot study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:322–7.

Ousley J, Soe KP, Kyaw NTT, Anicete R, Mon PE, Lwin H, et al. IPT during HIV treatment in Myanmar: high rates of coverage, completion and drug adherence. Public Health Action. 2018;8:20–4.

World Health Organization. Stop TB Partnership. High Burden Countries. UNOPS. http://www.stoptb.org/countries/tbdata.asp. Accessed 23 Aug 2020.

United Republic of Tanzania National AIDS Control Programme. National Guidelines for the Management of HIV and AIDS. United Republic of Tanzania National AIDs Control Program; 2009. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/tanzania_art.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2020.

The First National Tuberculosis Prevalence Survey in the United Republic of Tanzania Final Report. United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; 2013. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/77101834.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2020.

le Roux SM, Cotton MF, Golub JE, le Roux DM, Workman L, Zar HJ. Adherence to isoniazid prophylaxis among HIV-infected children: a randomized controlled trial comparing two dosing schedules. BMC Med. 2009;7:67.

Kew KM, Malik P, Aniruddhan K, Normansell R. Shared decision-making for people with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017.

World Health Organization Secretariat. Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Geneva: WHO; 2016. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39-en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 23 Aug 2020.

van Zyl S, Marais BJ, Hesseling AC, Gie RP, Beyers N, Schaaf HS. Adherence to anti-tuberculosis chemoprophylaxis and treatment in children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(1):13–8.

Cruz AT, Starke JR. Completion Rate and Safety of Tuberculosis Infection Treatment With Shorter Regimens. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20172838.

Van Wyk SS, Hamade H, Hesseling AC, Beyers N, Enarson DA, Mandalakes AM. Recording isoniazid preventive therapy delivery to children: operational challenges. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:650–3.

Martelli G, Antonucci R, Mukurasi A, Zepherine H, Nöstlinger C. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment among children and adolescents in Tanzania: comparison between pill count and viral load outcomes in a rural context of Mwanza region. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0214014.

Soobratty MR, Whitfield R, Subramaniam K, Grove G, Carver A, O'Donovan GV, et al. Point-of-care urine test for assessing adherence to isoniazid treatment for tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(5):1519–22.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the clinic staff and the patients and their families who participated in this study and entrusted their care to our clinical staff. We would also like to thank the Dickey Center for International Understanding at Dartmouth College and The Center for Health Equity at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth for supporting student internships to travel to Tanzania and engage in research at DPP.

Funding

A portion of this work was supported by the National Institute of Health’s Fogarty International Center, award 5D43TW009573–07. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OFH analyzed and interpreted the study data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. FK co-designed the study protocol and oversaw study implementation. ZND and AKA collected and cleaned patient enrollment data and performed preliminary analyses. PM and CFvR contributed to the study design and manuscript. LVA co-designed the study, contributed greatly in writing the manuscript, and provided study oversight. All authors read this manuscript and approved it for publication.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the National Institute for Medical Research in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) Institutional Review Board in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; and the Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects in Hanover, NH, USA.

Verbal informed consent was obtained in Kiswahili using a standardized form, which included counseling on the risks and benefits of IPT. Informed consent was obtained from parent/caregivers on behalf of the children. Children who were able to (typically those over age 5) also provided verbal assent. Consent was documented on a standardized form that was included in patients’ paper study record. Obtaining verbal informed consent was approved by the institutional review boards and ethics committees that reviewed this study. This method of informed consent was chosen because IPT was already a national Ministry of Health recommendation; however, it had not yet been implemented in most settings.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The author identified an error in the author name of C. Fordham von Reyn.

The incorrect author name is: C. F. von Reyn.

The correct author name is: C. Fordham von Reyn.

The author group has been updated above and the original article [1] has been corrected.

The author identified an error in the author name of C. Fordham von Reyn.

The incorrect author name is: C. F. von Reyn.

The correct author name is: C. Fordham von Reyn.

The author group has been updated above and the original article [1] has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hunter, O.F., Kyesi, F., Ahluwalia, A.K. et al. Successful implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy at a pediatric HIV clinic in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 20, 738 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05471-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05471-z