Abstract

Background

The widespread administration of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine has led to the predominance of non-typable H. influenzae (NTHi). However, the occurrence of invasive NTHi infection based on gynecologic diseases is still rare.

Case presentation

A 51-year-old Japanese woman with a history of adenomyoma presented with fever. Blood cultures and a vaginal discharge culture were positive with NTHi. With the high uptake in the uterus with 67Ga scintigraphy, she was diagnosed with invasive NTHi infection. In addition to antibiotic administrations, a total hysterectomy was performed. The pathological analysis found microabscess formations in adenomyosis.

Conclusions

Although NTHi bacteremia consequent to a microabscess in adenomyosis is rare, this case emphasizes the need to consider the uterus as a potential source of infection in patients with underlying gynecological diseases, including an invasive NTHi infection with no known primary focus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Haemophilus influenzae, a gram-negative coccobacillus, is a common cause of respiratory tract infections (e.g., pneumonia) and meningitis, particularly in children [1,2,3]. Although H. influenzae type b (Hib) is a notoriously virulent serotype of this species [4], the introduction of routine conjugate Hib vaccination led to a decrease in the number of cases of Hib infection [5]. Over the past decades, however, this decrease was paralleled by an increase in the frequency of non-typable H. influenzae (NTHi) infection, which now accounts for the majority of invasive H. influenzae infection cases [6,7,8,9].

In Japan, a recent nationwide population-based surveillance study revealed that NTHi and H. influenzae type f became the predominant isolates associated with invasive H. influenzae infection after the introduction of the Hib vaccine [10]. Previous studies have identified invasive NTHi infection as a cause of sepsis in adults, including pregnant women [11]. While previous reports have established the urogenital tract as a potential cause of invasive H. influenzae infection, no reports have described a specific association of NTHi infection with adenomyoma. Here, we report a case of invasive NTHi infection associated with a massive adenomyosis in an immunocompetent Japanese woman.

Case presentation

A 51-year-old Japanese woman with a history of adenomyoma was admitted to our hospital with fever. Four months before the admission, she had been referred to a gynecologist because of menorrhagia and metrorrhagia and was clinically diagnosed with a massive polypoid adenomyoma (PAM). Three days prior to hospital admission, she complained of fever as high as 40 °C, chills, and lower abdominal discomfort and revisited a nearby clinic, which referred her to our hospital upon suspicion of uterine infection.

During the examination, the patient was alert and oriented. She had a body temperature of 39.4 °C and a respiratory rate of 26/min. A physical examination revealed mild lower abdominal tenderness upon palpation. Other physical examinations, including a pelvic examination by a gynecologist, were noncontributory. Her medical history was significant for a massive adenomyoma but otherwise unremarkable. Blood testing upon admission revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 1.61 × 104/μL with neutrophil predominance and an elevated C-reactive protein concentration of 21.13 mg/dL. The serum immunoglobulin and complement component concentrations were within normal ranges. A urinalysis revealed no pyuria or bacteriuria, and direct urine polymerase chain reaction analyses for chlamydia and gonorrhea were negative. A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the massive adenomyosis of the uterus but revealed no evidence of uterine abscess formation, pyelonephritis, other sources of fever, or asplenia. Intravenous ceftriaxone treatment was initiated after two sets of blood cultures, a urine culture, and a vaginal discharge culture were obtained.

One day after admission, the blood culture analysis yielded a positive result for Gram-negative coccobacilli (BD BACTEC™ FX blood culture system, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA). The organism was subsequently identified as H. influenzae according to a positive X and V factor test (Haemophilus Differentiating Medium, Kyokuto Pharmaceutical Industrial Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), biochemical assay (ID test HN-20 rapid, Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), and mass spectrometry analysis (MALDI Biotyper, Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA, USA), which led to the diagnosis of invasive H. influenzae infection.

On the second day after admission, the vaginal discharge bacterial culture also yielded a positive result indicating H. influenzae. Both the blood and vaginal specimens were subjected to an antimicrobial resistance pattern analysis (Dryplate broth microdilution panels, Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and slide agglutination test with six specific antisera against each type of bacterial capsular polysaccharide (Bacterial antisera “SEIKEN”, Denka Seiken Co., Ltd., Japan), which identified the causative organism as NTHi with a β-lactamase-nonproducing ampicillin-resistance pattern. The result of antimicrobial susceptibility testing is shown in Table 1. The antimicrobial susceptibility profiles were identical for both isolates from the blood culture and vaginal discharge.

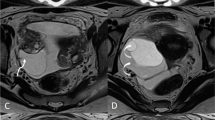

The patient remained febrile for 3 consecutive days, despite continued intravenous ceftriaxone therapy. A pelvic CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging with contrasts were performed to detect abscess formation in the uterus. However, the results were inconclusive (Figs. 1 and 2). Intravenous ceftriaxone therapy was continued based on the drug susceptibility test results. The patient became afebrile 7 days after admission. Meanwhile, we performed gallium-67 (67Ga) scintigraphy to evaluate the uterine infection, as no other possible origin of the febrile infection had been identified. The analysis revealed high 67Ga uptake confined to the internal layer of the uterus (Fig. 3). A total hysterectomy was performed 17 days after admission due to the high likelihood of uterine H. influenza infection. Although no grossly apparent uterine sources of infection were identified, the pathological analysis revealed microabscess formation in the enlarged uterus (Fig. 4), which was compatible with a uterine H. influenzae infection based on the underlying adenomyosis. The pathological diagnosis also revealed an early-stage endometrioid carcinoma. The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she did not receive additional antibiotic administration. She was discharged home a month after admission and was instructed to participate in outpatient gynecological follow-up.

Gallium-67 (67Ga) scintigraphy of the uterus after prednisone treatment. 67Ga scintigraphy revealed high uptake in the intrauterine cavity (arrow), which suggested an active infection in the uterus. High 67Ga uptake was not observed in other organs. a anterior and posterior images of 67Ga scintigraphy; b horizontal view

Discussion and conclusions

Although H. influenzae typically colonizes the respiratory tracts, it has been reported that a few women might carry NTHi in their genital tracts [12]. The comparatively widespread nature of NTHi consequent to the use of Hib vaccine in recent years emphasizes the need to familiarize ourselves with this important pathogen [7, 8]. Our present case not only involved a rare occurrence of an invasive H. influenzae infection associated with adenomyosis, but also presents several lessons for those dealing with infectious disease in their daily practices. First, the presence of a gynecologic disease, such as adenomyosis, may become a nidus of complicated NTHi infection. Second, even in a case involving a complicated uterine infection, appropriate cultures and a pathological diagnosis are essential tools for detecting the sources of infections.

Previously, only a few articles reported association of gynecological diseases with H. influenzae infection. For example, Chen et al. reported a case of H. influenzae vulvovaginitis in a prepubertal girl [13]. Martin and colleagues described a case of NTHi bacteremia due to acute endometritis, in which the uterus appeared to be the nidus of NTHi infection with no known primary focus [14]. Also, it has been reported that Haemophilus quentini, a NTHi biotype IV isolate, may have a predilection for female urogenital tract [15]. While identification of H. quentini isolates are not currently feasible at frontline laboratories, it is worth noting that NTHi could be an important causative pathogen of gynecological infections. Adenomyosis is a common gynecological disease involving ectopic endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. A PAM is defined as an adenomyoma that has protruded into the endometrial cavity [16], and can be divided histopathologically into typical and atypical types. An atypical PAM comprises a mixture of epithelial and mesenchymal components, and different degrees of atypia, including endometrioid carcinoma, may be present within the endometrial glands [17]. The diagnosis of PAM is difficult, and pathological analysis is imperative. Although this case was finally diagnosed as adenomyosis, based on previous reports that have described invasive NTHi cases attributed to endometriosis and pregnancy [6, 14], we may infer that any anatomical abnormality in the female reproductive organs could be a nidus of bacterial infection.

The determination and diagnosis of the uterus as a source of infection, as in this case, remains challenging, despite the importance of this organ with regard to invasive NTHi infection. As per the World Health Organization (WHO), both the collection of a swab bacterial culture and a pelvic examination are essential when evaluating a case with a high clinical suspicion of a reproductive system infection [18]. Moreover, the combination of pathological analyses is encouraged to strengthen the diagnostic accuracy, as underscored by a previous report in which H. influenzae was detected in an endometrial tissue biopsy specimen [14]. In our case, the antimicrobial resistance pattern and phenotypes of H. influenzae detected in the blood cultures coincided with those in the vaginal discharge culture. The addition of 67Ga scintigraphy and pathological analyses of the uterus helped to confirm the diagnosis.

In conclusion, we have presented a case of invasive NTHi infection associated with adenomyosis. Clinicians faced with a patient with no known primary focus of H. influenzae bacteremia and an underlying gynecological disease should consider the uterus as a possible source of infection.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 67Ga:

-

Gallium-67

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- Hib:

-

H. influenzae type b

- NTHi:

-

Non-typable Haemophilus influenzae

- PAM:

-

Polypoid adenomyoma

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Chan PC, Lu CY, Lee PI, Yang TY, Chen RT, Ho YH, et al. Haemophilus influenzae type b meningitis with subdural effusion: a case report. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2002;35(1):61–4.

Slack MPE. A review of the role of Haemophilus influenzae in community-acquired pneumonia. Pneumonia (Nathan). 2015;6:26–43. https://doi.org/10.15172/pneu.2015.6/520.

Wang S, Tafalla M, Hanssens L, Dolhain J. A review of Haemophilus influenzae disease in Europe from 2000-2014: challenges, successes and the contribution of hexavalent combination vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16(11):1095–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14760584.2017.1383157.

Shimizu S, Tahara Y, Atsumi T, Imai Y, Ueda H, Seo R, et al. Waterhouse-friderichsen syndrome caused by invasive haemophilus influenzae type B infection in a previously healthy young man. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38(1):214–5.

Morris SK, Moss WJ, Halsey N. Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine use and effectiveness. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(7):435–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70152-X.

Diseases TNIoI. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae infections in Japan. 2014. https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/en/865-iasr/4223-tpc401.html. Accessed 8th Mar 2020.

Giufre M, Fabiani M, Cardines R, Riccardo F, Caporali MG, D'Ancona F, et al. Increasing trend in invasive non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae disease and molecular characterization of the isolates, Italy, 2012-2016. Vaccine. 2018;36(45):6615–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.060.

Dong Q, Shi W, Cheng X, Chen C, Meng Q, Yao K, et al. Widespread of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae with high genetic diversity after two decades use of Hib vaccine in China. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019:e23145. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23145.

Harama D, Kobayashi K, Toda T, Sugita K, Ikeda H. Infective endocarditis caused by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. Pediatr Int. 2020;62(1):114–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.14046.

Suga S, Ishiwada N, Sasaki Y, Akeda H, Nishi J, Okada K, et al. A nationwide population-based surveillance of invasive Haemophilus influenzae diseases in children after the introduction of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine in Japan. Vaccine. 2018;36(38):5678–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.029.

Collins S, Ramsay M, Slack MP, Campbell H, Flynn S, Litt D, et al. Risk of invasive Haemophilus influenzae infection during pregnancy and association with adverse fetal outcomes. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1125–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.1878.

Schonheyder H, Ebbesen F, Grunnet N, Ejlertsen T. Non-capsulated Haemophilus influenzae in the genital flora of pregnant and post-puerperal women. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23(2):183–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365549109023398.

Chen X, Chen L, Zeng W, Zhao X. Haemophilus influenzae vulvovaginitis associated with rhinitis caused by the same clone in a prepubertal girl. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(6):1080–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.13311.

Martin D, Dbouk RH, Deleon-Carnes M, del Rio C, Guarner J. Haemophilus influenzae acute endometritis with bacteremia: case report and literature review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76(2):235–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.010.

Kus JV, Shuel M, Soares D, Hoang W, Law D, Tsang RSW. Identification and Characterization of "Haemophilus quentini" Strains Causing Invasive Disease in Ontario, Canada (2016 to 2018). J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57(12). https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01254-19.

Sajjad N, Iqbal H, Khandwala K, Afzal S. Polypoid Adenomyoma of the uterus. Cureus. 2019;11(2):e4044. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4044.

Bai TJ, Bao DM, Li Y, Wang Y, Cui H, Zhu HL. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus: a clinicopathological review of 27 cases. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2017;52(4):244–8. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-567X.2017.04.006.

Organization WH. Sexually transmitted and other reproductive tract infections: A guide to essential practice. 2005. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43116/9241592656.pdf;jsessionid=675D14AA015694F5ED715FF302F9957C?sequence=1. Accessed 12th Mar 2020.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written by YN and HH. KK, YY, KO, KI, KH and MO conducted the literature review and revised the manuscript. TH and SO acquired the data. HM and FO analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors had the patient’s written consent for publication of this case report including the personal and clinical details and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishimura, Y., Hagiya, H., Kawano, K. et al. Invasive non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae infection due to endometritis associated with adenomyosis. BMC Infect Dis 20, 521 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05193-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05193-2