Abstract

Background

About 80% of all reported sickle cell disease (SCD) cases in children anually are recorded in Africa. Although malaria is considered a major cause of death in SCD children, there is limited data on the safety and effectiveness of the available antimalarial drugs used for prophylaxis. Also, previous systematic reviews have not provided quantitative measures of preventive effectiveness. The purpose of this research was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature to determine the safety and effectiveness of antimalarial chemoprophylaxis used in SCD patients.

Methods

We searched in PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, POPLine and Cochrane library, for the period spanning January 1990 to April 2018. We considered randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials comparing any antimalarial chemoprophylaxis to, 1) other antimalarial chemoprophylaxis, 2) placebo or 3) no intervention, in SCD patients. Studies comparing at least two treatment arms, for a minimum duration of three months, with no restriction on the number of patients per arm were reviewed. The data were extracted and expressed as odds ratios. Direct pairwise comparisons were performed using fixed effect models and the heterogeneity assessed using the I-square.

Results

Six qualified studies that highlighted the importance of antimalarial chemoprophylaxis in SCD children were identified. In total, seven different interventions (Chloroquine, Mefloquine, Mefloquine artesunate, Proguanil, Pyrimethamine, Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine amodiaquine) were evaluated in 912 children with SCD. Overall, the meta-analysis showed that antimalarial chemoprophylaxis provided protection against parasitemia and clinical malaria episodes in children with SCD. Nevertheless, the risk of hospitalization (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.267–1.959; I2 = 0.0%), blood transfusion (OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.542–1.280; I2 = 29.733%), vaso-occlusive crisis (OR = 19, 95% CI = 1.713–2.792; I2 = 93.637%), and mortality (OR = 0.511, 95% CI = 0.189–1.384; I2 = 0.0%) did not differ between the intervention and placebo groups.

Conclusion

The data shows that antimalarial prophylaxis reduces the incidence of clinical malaria in children with SCD. However, there was no difference between the occurrence of adverse events in children who received placebo and those who received prophylaxis. This creates an urgent need to assess the efficacy of new antimalarial drug regimens as potential prophylactic agents in SCD patients.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO (CRD42016052514).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of autosomal recessive inherited disorders caused by a single nucleotide substitution (T > A) in the β-globin gene. The mutation (Glu6Val) promotes polymerization of deoxygenated sickle haemoglobin S (HbS) and decreased deformability of red blood cells resulting in obstruction of the vasculature and a range of pathophysiological effects including vaso-occlusion, organ ischaemia, infarction, and early mortality [1]. SCD accounts for 5–19% mortality in children in sub-Saharan Africa, where the highest frequency of homozygous SCD occurs [2]. SCD-related mortality occurs mostly in undiagnosed infants in sub-Saharan Africa, and is predominantly attributed to infections, including malaria [3]. Although a linkage exists between the presence of sickle haemoglobin (HbS) and protection from malaria in the heterozygous state [4], malaria is a frequent cause of hospitalization and poor outcome among children with SCD in endemic areas [5, 6], and malaria is associated with a higher mortality in hospitalized SCD patients compared to hospitalized non-SCD patients [7,8,9]. Prophylaxis against malaria is therefore important in SCD patients, as antimalarial chemoprophylaxis has also been shown to be beneficial in SCD patients, reducing parasitaemia and anaemia, and the requirement for blood transfusion [10,11,12].

The WHO recommends that SCD patients in endemic areas should receive antimalarial prophylaxis [13, 14]; however, the evidence to support the potential beneficial effects of this strategy in SCD patients is limited: i) almost all previous individual studies were underpowered to detect some clinically important outcomes, and ii) whereas an early systematic review included two small studies [15], a latter review that included six randomized trials provided descriptive information [16]. There is no consensus on the optimal chemoprophylactic regimen for SCD patients especially in the context where artemisinin-based regimens are the treatment standard. There is also lack of data on the comparative effect of different antimalarial chemoprophylactic regimens that have never been compared directly in randomized clinical trials, and data on the overall effect of chemoprophylactic regimens in trials with more than two arms are non-existent. In the absence of direct head-to-head comparisons on interventions, network meta-analysis provides a statistical framework that incorporates evidence from both direct and indirect comparisons from a network of studies of different therapies to evaluate their relative effects. This systematic review was conducted to provide an update on existing evidence based on new studies published and compare drugs that have been used in this context.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We considered randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials comparing any antimalarial chemoprophylactics to, 1) other antimalarial chemoprophylactics, 2) placebo or 3) no intervention, in SCD patients. The selection included studies that compared at least two treatment arms, for a minimum duration of three months, with no restriction on the number of patients per arm. The search was conducted between May 2016 and April 2018 in, PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, POPLine and Cochrane library, for the period spanning January 1990 to April 2018. The MeSH terms for the search included a combination of the following terms, sickle cell disease, malaria, malaria chemoprophylaxis, chemoprophylactics, malaria chemotherapy(y)ies, mortality, hospitalization, morbidity, effectiveness of, antimalarial therapy, antimalarial drugs, malaria therapy, malaria treatment, malaria prophylaxis, safety of, safety and effectiveness, randomized trials, randomized control trials, quasi-randomized trials. Studies that met the inclusion criteria and published in English were included. Non-peer reviewed articles and other publication types were used to guide in the search for further literature (technical reports, theses, working papers). We also contacted authors for supplementary information relating to the haematological parameters. Citations and articles were downloaded and organized using EndNote (versionX5).

Data screening and study selection

Two independent reviewers conducted the search, screened titles and abstracts and removed duplicate publications. However, no informative result was obtained from the grey literature search. Studies that did not indicate the use of any of the interventions were excluded. Subsequently, full-text articles were retrieved, screened and retained if they met the inclusion criteria. The two independent reviewers extracted data with data abstraction forms which included details about the study design, sample size, recruitment method, data characteristics, location, study period, interventions, and outcome. All disagreements on study inclusion criteria were referred to a third member of the study team for resolution.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The quality of the studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, identifying the presence or otherwise of key concepts or themes relating to antimalarial intervention trials including, random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete data reporting, selective reporting, and other bias [17].

Outcome measures

The pre-specified primary outcome measures were, 1) safety and 2) effectiveness of the antimalarial chemoprophylactics for SCD patients. Safety was defined as, the ability of the intervention to minimize the occurrence of undesirable outcomes (adverse events, changes in haematological parameters) and, effectiveness, as the ability of the intervention a) to decrease detectable parasitaemia and/or b) to limit the number of clinical malaria episodes. Other outcome measures included mortality as associated with a clinical malaria episode, or vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC), and the number of VOC episodes.

Statistical analysis

The Comprehensive meta-analysis software version 3 was used to conduct direct pair-wise meta-analyses using placebo as a control. Outcomes were expressed as odds ratios and fixed effect methods were used to estimate the mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I-squared (I2), and a network of randomized controlled trials was also conducted based on the frequentist approach using the netmeta package in R studio version 2 [18]. We performed direct and indirect pairwise comparisons which provided the odds ratio from a fixed effect model with 95% confidence intervals from the estimates. Treatments were ranked using the P-scores for the effectiveness of the intervention.

Results

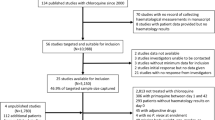

The initial search resulted in a total of 1202 records, of which 759 were retained after excluding duplicate publications. A total of five studies met the criteria for inclusion, and subsequently, an additional study (n = 1) was included from the bibliography of screened studies. The flow diagram for selection and inclusion of studies is shown (Fig. 1). A total of six randomized controlled trials, including two trials that included three arms [14, 19], and four trials that included two arms [20,21,22,23] were included in the meta-analysis. A total of 912 SCD patients were included in the six studies, and the following seven chemoprophylactic regimens [(a) Proguanil (PG); (b) Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine (SP); (c) Mefloquine (MQ); (d) Chloroquine (CQ); (e) Pyrimethamine (PM); (f) Mefloquine-Artesunate (MQAS); and (g) Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine-Amodiaquine (SPAQ)] were evaluated in the meta-analysis. A total of 831 enrolled participants completed follow up periods ranging from five months [21] to twenty-one months [23]. The largest number of participants in a trial were enrolled in trials that included PG (n = 182) and CQ (n = 182) arms, followed by trials that included an SP arm (n = 150), MQAS arm (n = 90), SPAQ arm (n = 90), MQ arm (n = 56), and PM (n = 36) (Table 1). The methodological quality of all included trials was assessed as good, allocation concealment was appropriate, and all but one study provided an adequate report on adverse events occurring in the respective treatment arms. However, only one of the studies [21] described an adequate blinding procedure (Table 2).

Comparator drugs

In all, PG was the most common active comparator drug and was also the most commonly evaluated stand-alone drug [14, 19, 22]: it was compared with four different interventions in three different studies (Table 1) [14, 19, 22]. SPAQ and MQAS were each compared with two different interventions in one single study [19], and CQ was evaluated as a stand-alone drug in one study [21], and in combination with benzathine penicillin in an early intervention study [23]. SP, MQ and PM, were each compared to a single intervention at a time in single studies (Table 1; Fig. 2). The network of eligible comparisons for outcome measures is shown (Fig. 2). Efficacy and tolerability were evaluated as outcome measures in six interventions out of the 21-possible pair-wise comparisons between the seven interventions. All the interventions (except studies evaluating MQAS, SPAQ or PG), included at least one placebo-controlled trial, and the majority of the interventions also directly compared at least one active comparator (Table 1).

Parasitaemia and/or clinical malaria episodes

All the included studies provided data on the number of clinical malaria episodes and/or the number of patients presenting with detectable parasitaemia during the follow-up period (Table 1). The cumulative odds ratio of the effectiveness of the interventions was 0.76 (95% CI = 0.591–0.97; I2 = 79.6%) (Fig. 3). Overall, SCD patients receiving prophylaxis were less likely to harbour detectable parasitaemia or to present with a clinical malaria episode compared to the placebo group (relative risk reduction of 24%) (Fig. 3). Taken individually, SP and CQ seemed to provide better protection compared to the rest of the interventions (Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Summary plot showing the effectiveness of the chemoprophylaxis with placebo as a reference. Antimalarial drugs were compared to placebo with the risk of developing malaria. Each single drug was represented as a square. The square area denotes the contribution of the drug to the meta-analysis. Horizontal line denotes the odds ratio and the confidence interval. The diamond represents the combined odds ratio with confidence interval. Odds ratios lower than 1 favour interventions and 95% CI values (Lower limit and Upper limit) comprised between 0 and 1 is associated with a significant difference

Adverse event occurrence

The majority of studies (a total of five out of six) provided information about adverse event occurrence (Table 1), Reported adverse events were mostly minor (e.g., vomiting, body pain, weakness, pruritus, headache, and nausea), with the most commonly reported major adverse events being, hospitalization, blood transfusion, vaso-occlusive crisis and mortality. The cumulative odds ratio of adverse event occurrence in the intervention arm was 0.72 (95% CI = 0.267–1.959; I2 = 0.0%) for hospitalisation (Fig. 4a); 0.83 (95% CI = 0.542–1.280; I2 = 29.733%) for blood transfusion (Fig. 4b); 2.19 (95% CI = 1.713–2.792; I2 = 93.637%) for vaso-occlusive crisis (Fig. 4c) and 0.511 (95% CI = 0.189–1.384; I2 = 0.0%) for mortality (Fig. 4d). Compared to placebo, all interventions were associated with a marginally reduced risk of hospitalization, except CQ and MQAS (95% CI for the population included 1.0 for all treatments) (Fig. 4a), and no significant difference in the risk of blood transfusion was present between those who received an intervention or placebo, except for PM recipients (Fig. 4b). Unexpectedly, the risk of vaso-occlusive crisis occurrence was more likely in PG, MQAS and SPAQ recipients compared to placebo, but less likely in those who received CQ and SP (Fig. 4c). All the studies reported mortality outcomes (Table 1). However, aside from the placebo group, mortality was reported in only two groups, (PG and MQAS), the latter reporting a higher mortality risk rate (Fig. 4d).

Forest plots showing the commonly reported adverse-events related to the antimalaria chemoprophylaxis in SCD patients. Results are shown for (a) hospitalization, (b) blood transfusion, (c) vaso-occlusive crisis and (d) mortality with placebo as a reference. The square area denotes the contribution of the drug to the meta-analysis. Horizontal line denotes the odds ratio together with the confidence intervals. The diamond represents the combined odds ratio with its confidence interval. Odd Ratios lower than 1 favour interventions and 95% CI values (Lower limit and Upper limit) comprised between 0 and 1 is associated with a significant difference

Sickle cell crises and changes in hematological parameters

None of the eligible studies reported significant differences in the number of sickle cell crises or changes in hematological parameters (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Discussion

This systematic review has provided an opportunity to provide quantitative data on the safety and efficacy of antimalarial prophylactic drugs in SCD patients, thus extending the available summary evidence on this indication. The network meta-analysis component has also enabled a comparison of all active comparator drugs used in clinical trials of antimalarial prophylaxis in SCD to date, thus, increasing the chances of generating an internally consistent set of estimates while respecting the randomization in the original trials. Due to the lack of standard basis to normalize the data from different studies while conducting the network meta-analysis, our main focus remained on the pairwise meta-analysis to assess both the efficacy and safety of individual interventions.

The results from this meta-analysis shows that anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis provided protection against parasitemia and clinical malaria episodes in children with SCD. However, the results show that the intervention did not have an effect on the risk of hospitalization, need for blood transfusion, vaso-occlusive crises and mortality in SCD patients.

In this study, we observed that PG was the commonest chemoprophylaxis used in three of the six studies [14, 19, 22], partly because these studies were conducted in Nigeria where PG is the recommended IPT for SCD patients. In addition, it could be due to the relative safety of this antimalarial drug [24], an important characteristic in such a vulnerable target group and for such an indication. However, parasitaemia was reported in all the studies in which PG was used as prophylaxis. This may be due to sub-optimal compliance, as PG is administered daily due to its relatively short half-life [25,26,27].

Although the results of the meta-analysis did not show a decrease in the incidence of blood transfusion and vaso-occlusive crises; an analysis of individual drugs showed a decreased in blood transfusion or anaemia in PM recipients. Also, the incidence of VOC was lower in CQ and SP recipients. The high likelihood of VOC observed in SCD patients on prophylaxis may be due to presence of Plasmodium infection or parasitemia. Despite the fact that the development of VOC requires the interplay of various factors [28], it may be exacerbated by malaria infection. However most of these studies were conducted in the era preceding the evolution of widespread resistance to these antimalarial drugs.

Due to this, the use of anti-malarial monotherapies as prophylaxis in a group as vulnerable as sickle cell disease patients is of utmost concern [29,30,31,32], as the two drugs (CQ and SP) that showed protective efficacy are no longer recommended for treatment because of widespread resistance. Although the use of combination therapy is currently recommended, available evidence indicates that the efficacy of such drugs (e.g., SPAQ and MQAS), were relatively low in SCD patients despite evidence of their increased efficacy in individuals with normal HbAA genotypes [33, 34]. Therefore, it is imperative that new studies with currently available antimalarial prophylactic drugs be conducted in SCD patients.

Also, the meta-analysis data showed a higher MQ-related adverse event incidence, both in studies in which MQ was evaluated as a stand-alone drug [22], as well as in studies in which the drug was used in combination with AS [19]. This finding is consistent with the dose-dependent association of MQ with neuropsychiatric adverse events [35]. Nevertheless, only one of the studies in which MQ was evaluated [19] provided details about the MQ dosing regimen. This finding may suggest that alternative prophylactic regimens other than mefloquine may be more desirable for prophylaxis in SCD patients.

We could not identify any previous studies evaluating the safety or efficacy of currently recommended ACT regimens as components of prophylactic regimens in SCD patients. The only available (two) studies [36, 37] that have reported on the safety of ACTs among children with haemoglobinopathies reported an improved outcome in some selected haematological indices following treatment with ACTs in these groups of children. However, as concluded by a recent systematic review on ACTs and malaria in haemoglobinopathies, the efficacy of these ACTs when used as prophylaxis in haemoglobinopathies is yet to be proven [38]. This implies that, there is still limited evidence on the safety and efficacy of antimalarial prophylaxis in SCD patients and therefore, highly recommended that new antimalarial drugs should be evaluated for their efficacy and safety specifically in SCD patients.

The limitations of this study include the fact that the analysis included 912 patients; while this sample size is modest and likely to affect the outcome of low-incidence variables (e.g., mortality), it is unlikely to affect outcomes such as parasitaemia or VOC. Furthermore, the limited number of studies, coupled with the small sample size of individual studies, as well as study quality and other implementation challenges could account for the observed substantial heterogeneity in the outcome parameters. These may have also accounted for the lack of association between safety parameter outcomes and antimalarial prophylaxis observed in the analysis.

Conclusion

The data shows that the use of antimalarial drugs as prophylaxis in sickle cell disease patients results in reduction in incidence of malaria; whereas the incidence of hospitalisation, blood transfusion, vaso-occlusive crises and mortality were not different between SCD patients on prophylaxis compared to those on placebo. Nonetheless, using stand-alone drugs, SCD patients using PM, had a reduction in hospitalization compared to patients on any of the other prophylaxis or placebo, while CQ or SP prophylaxis were also associated with reduced occurrence of vaso-occlusive crises.

The findings indicate that there is non-existent data on currently recommended antimalarial drugs as prophylaxis in SCD patients thus, there is a need to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new antimalarial drugs including the utility of currently recommended ACT regimens, as potential prophylactic agents in SCD patients.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Artemisinin combination therapy

- CQ:

-

Chloroquine

- HbS:

-

Haemoglobin S

- IPT:

-

Intermittent preventive threatment

- MQ:

-

Mefloquine

- MQAS:

-

Mefloquine-Artesunate

- PM:

-

Pyrimethamine

- PQ:

-

Proguanil

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- SCD:

-

Sickle cell disease

- SP:

-

Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine

- SPAQ:

-

Sulphadoxine-Pyrimethamine-Amodiaquine

- VOC:

-

Vaso-occlusive crisis

References

Bartolucci P, Galacteros F. Clinical management of adult sickle-cell disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19(3):149–55.

WHO. Sickle-cell anaemia. In. Edited by A59/9. R. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

Diallo DA, Baby M, Boire A, Diallo YL. Management of pain of acute sickle cell pain crises by health care providers in Mali. Med Trop (Mars). 2008;68(5):502–6.

Williams TN, Mwangi TW, Wambua S, Alexander ND, Kortok M, Snow RW, Marsh K. Sickle cell trait and the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and other childhood diseases. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(1):178–86.

Aluoch JR. Higher resistance to Plasmodium falciparum infection in patients with homozygous sickle cell disease in western Kenya. Tropical Med Int Health. 1997;2(6):568–71.

Maharajan R, Fleming AF, Egler LJ. Pattern of infections among patients with sickle cell anemia requiring hospital admission. Niger J Paediatr. 1983;10:5.

Ambe JP, Fatunde JO, Sodeinde OO. Associated morbidities in children with sickle-cell anaemia presenting with severe anaemia in a malarious area. Trop Dr. 2001;31(1):26–7.

Makani J, Komba AN, Cox SE, Oruo J, Mwamtemi K, Kitundu J, Magesa P, Rwezaula S, Meda E, Mgaya J, et al. Malaria in patients with sickle cell anemia: burden, risk factors, and outcome at the outpatient clinic and during hospitalization. Blood. 2010;115(2):215–20.

McAuley CF, Webb C, Makani J, Macharia A, Uyoga S, Opi DH, Ndila C, Ngatia A, Scott JA, Marsh K, et al. High mortality from Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children living with sickle cell anemia on the coast of Kenya. Blood. 2010;116(10):1663–8.

Fleming AF. The presentation, management and prevention of crisis in sickle cell disease in Africa. Blood Rev. 1989;3(1):18–28.

Konotey-Ahulu FID. Malaria and sickle-cell disease. Br Med J. 1971;2:763.

Konotey-Ahulu FID, Serjeant G, White JM. Treatment and prevention of sickle cell crisis. Lancet. 1971;2(7736).

WHO. Sickle-Cell Disease: A strategy for the WHO African Region Report of the Regional Director. In: Sixtieth session. Malabo: Equatorial Guinea; 2010. p. 30.

Eke FU, Anochie I. Effects of pyrimethamine versus proguanil in malarial chemoprophylaxis in children with sickle cell disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled, open-label study. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2003;64(8):616–25.

Oniyangi O, Omari AA. Malaria chemoprophylaxis in sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD003489.

Aneni EC, Hamer DH, Gill CJ. Systematic review of current and emerging strategies for reducing morbidity from malaria in sickle cell disease. Tropical Med Int Health. 2013;18(3):313–27.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2011;343:d5928.

Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Krahn U, Jochem König J. Package'netmeta', version 0.8–0, network meta-analysis using frequentist methods. R Library. Repository CRAN. 2015;18:23.

Olaosebikan R, Ernest K, Bojang K, Mokuolu O, Rehman AM, Affara M, Nwakanma D, Kiechel JR, Ogunkunle T, Olagunju T, et al. A randomized trial to compare the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of 3 antimalarial regimens for the prevention of malaria in Nigerian patients with sickle cell disease. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(4):617–25.

Diop S, Soudre F, Seck M, Gueye YB, Dieye TN, Fall AO, Sall A, Thiam D, Diakhate L. Sickle-cell disease and malaria: evaluation of seasonal intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in Senegalese patients-a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Hematol. 2011;90(1):23–7.

Nakibuuka V, Ndeezi G, Nakiboneka D, Ndugwa CM, Tumwine JK. Presumptive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine versus weekly chloroquine for malaria prophylaxis in children with sickle cell anaemia in Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. Malar J. 2009;8:237.

Nwokolo C, Wambebe C, Akinyanju O, Raji AA, Audu BS, Emodi IJ, Balogun MO, Chukwuani CM. Mefloquine versus Proguanil in short-term malaria chemoprophylaxis in sickle cell Anaemia. Clin Drug Invest 2. 2001;21(8):8.

Warley MA, Hamilton PJ, Marsden PD, Brown RE, Merselis JG, Wilks N. Chemoprophylaxis of homozygous Sicklers with Antimalarials and long-acting penicillin. Br Med J. 1965;2(5453):86–8.

Kain KC, Shanks GD, Keystone JS. Malaria chemoprophylaxis in the age of drug resistance. I. Currently recommended drug regimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(2):226–34.

McGready R, Stepniewska K, Edstein MD, Cho T, Gilveray G, Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Nosten F. The pharmacokinetics of atovaquone and proguanil in pregnant women with acute falciparum malaria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59(7):545–52.

Soyinka JO, Onyeji CO. Alteration of pharmacokinetics of proguanil in healthy volunteers following concurrent administration of efavirenz. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;39(4):213–8.

Wattanagoon Y, Taylor RB, Moody RR, Ochekpe NA, Looareesuwan S, White NJ. Single dose pharmacokinetics of proguanil and its metabolites in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24(6):775–80.

Manwani D, Frenette PS. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology and novel targeted therapies. Blood. 2013;122(24):3892–8.

Lin JT, Juliano JJ, Wongsrichanalai C. Drug-resistant malaria: the era of ACT. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(3):165–73.

Plowe CV, Djimde A, Bouare M, Doumbo O, Wellems TE. Pyrimethamine and Proguanil resistance-conferring mutations in Plasmodium falciparum Dihydrofolate reductase: polymerase chain reaction methods for surveillance in Africa. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1995;52(6):565–8.

Plowe CV, Kublin JG, Doumbo OK. P. Falciparum dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase mutations: epidemiology and role in clinical resistance to antifolates. Drug Resist Updat. 1998;1(6):389–96.

Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Akinboye DO, Yusuf BO, Ebong OO, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, et al. Polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum dhfr and dhps genes and age related in vivo sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance in malaria-infected patients from Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2005;95(3):183–93.

Zongo I, Dorsey G, Rouamba N, Dokomajilar C, Séré Y, Rosenthal PJ, Ouédraogo JB. Randomized comparison of amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, artemether-lumefantrine, and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Burkina Faso. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(11):1453–61.

Sirima SB, Ogutu B, Lusingu JPA, Mtoro A, Mrango Z, Ouedraogo A, Yaro JB, Onyango KO, Gesase S, Mnkande E, et al. Comparison of artesunate-mefloquine and artemether-lumefantrine fixed-dose combinations for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children younger than 5 years in sub-Saharan Africa: a randomised, multicentre, phase 4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(10):1123–33.

Barrett PJ, Emmins PD, Clarke PD, Bradley DJ. Comparison of adverse events associated with use of mefloquine and combination of chloroquine and proguanil as antimalarial prophylaxis: postal and telephone survey of travellers. BMJ. 1996;313(7056):525–8.

Adjei GO, Goka BQ, Enweronu-Laryea CC, Rodrigues OP, Renner L, Sulley AM, Alifrangis M, Khalil I, Kurtzhals JA. A randomized trial of artesunate-amodiaquine versus artemether-lumefantrine in Ghanaian paediatric sickle cell and non-sickle cell disease patients with acute uncomplicated malaria. Malar J. 2014;13:369.

Ndounga M, Pembe Issamou M, Casimiro PN, Koukouikila-Koussounda F, Bitemo M, Diassivy Matondo B, Ndounga Diakou LA, Basco LK, Ntoumi F. Artesunate-amodiaquine versus artemether-lumefantrine for the treatment of acute uncomplicated malaria in Congolese children under 10 years old living in a suburban area: a randomized study. Malar J. 2015;14:423.

Sugiarto SR, Moore BR, Makani J, Davis TME. Artemisinin therapy for malaria in Hemoglobinopathies: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(5):799–804.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge WHO/TDR for providing training in systematic reviews and meta-analysis by funding through the “Short-term training grants for research capacity strengthening and knowledge management programme (ID no: B40414), and to the Building Stronger Universities Phase 2 Project at University of Ghana with funding from the DANIDA Fellowship Centre, Denmark. The authors are also grateful to Marcela Alfaro for her immense contribution to the data analysis, and to Laust Mortensen for assistance with the network meta-analysis.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials used for the analysis of this review are included in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GOA conceived the research idea; AF, LGT, and GOA developed and registered the study protocol; Systematic Review training and guidance was provided by EDAO, BAB and GOA; AF and LGT performed the literature search, determined relevant studies satisfying the inclusion criteria; GOA assessed and approved the quality of selected studies; AF and LGT extracted the data for analysis; AF and LGT performed the statistical analysis; GOA, LGT and AF drafted and wrote the final manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

AF and LGT are supported by a Ph.D. fellowship from a World Bank African Centres of Excellence Grant (ACE02-WACCBIP: Awandare); AF is also supported by the International Development Research Center grant from the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Ghana, a recipient of the L’Oreal-UNESCO for Women in Science Grant, the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the University of Ghana BanGA Ph.D. Grant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors have read and agreed to the content of this manuscript and its publication upon acceptance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Ranking the effectiveness of the interventions. A histogram plot showing the ranking probability on the effectiveness of the treatment. This was performed by using the point estimates and standard errors. SP=Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine, CQ = Chloroquine, MQ = Mefloquine, PG = Proguanil, PM = Pyrimethamine, PL = Placebo, MQAS = Mefloquine-Artesunate, SPAQ = Sulfadoxine Pyrimethamine-Amodiaquine. (DOCX 28 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Haematological parameters for safety profile. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Frimpong, A., Thiam, L.G., Arko-Boham, B. et al. Safety and effectiveness of antimalarial therapy in sickle cell disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 18, 650 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3556-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3556-0