Abstract

Background

Central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) are a major source of sepsis in modern intensive care medicine. Some years ago bundle interventions have been introduced to reduce CLABSI. The use of checklists may be an additional tool to improve the effect of these bundles even in highly specialized institutions. In this study we investigate if the introduction of a checklist reduces the frequency of CLABSI.

Methods

During the study period from October 2011 to September 2012, we investigated the effect of implementing a checklist for the placement of central venous lines (CVL). Patients were allocated either to the checklist group or to the control group, roughly in a 1:2 ratio. The frequency of CLABSI was compared between the two groups.

Results

During the study period 4416 CVL were inserted; 1518 in the checklist group and 2898 in the control group. The use of the checklist during CVL placement resulted in a lower CLABSI frequency. The incidence in the checklist group was 3.8 per 1000 catheter days as compared to 5.9 per 1000 catheter days in the control group (IRR = 0.57; p = 0.001). The use of the checklist also reduced the frequency of catheter colonisation significantly, 36.3 per 1000 catheter days in the checklist group vs 21.2 per 1000 catheter days in the control group, respectively (IRR = 0.58; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The introduction of a checklist to improve the adherence to hygiene standards while placement of central venous lines reduced the frequency of infections significantly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Central line-associated blood stream infections (CLABSI) are a major source of hospital acquired infections and an important contributor to the medical and financial burden in modern intensive care medicine [1,2,3,4].

Costs for a single blood stream infection are estimated at 16,500 US$ and the mortality of patients with CLABSI is 2–4 fold higher than that of similar patients without [4, 5]. Rigorous hygiene standards for placement and handling of central venous lines (CVL) are needed to prevent infections [6].

In high risk environments like aviation or nuclear power plants, checklists are standard tools to improve safety and prevent system breakdowns [7]. Knowledge transfer is not the primary intention of checklists. Pilots are trained to fly and physicians in an intensive care unit (ICU) are trained to place a CVL, thus the effect of checklists is to focus the attention of the persons involved on the actual task [7]. The use of checklists has been advocated by the World Health Organization to improve the safety of surgery and initial studies demonstrated a benefit [8]. Yet, some studies have questioned the general applicability of this approach [9]. Highly trained personnel and well established backup systems in place (e.g. blood banks, extra personnel on site, interdisciplinary support), have been put forward to explain these findings.

We aimed to assess the effect of introducing a checklist for the placement of a CVL on the frequency of CLABSI in ICU-patients in a setting of highly trained personnel in a large university hospital.

Methods

Setting and study design

This was an observational, prospective, single-center study at the Department of Intensive Care Medicine at the University Medical Center Hamburg–Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany from 1st October 2011 to 30th September 2012. The department consists of 11 wards with a total of 132 ICU beds for adult patients. Each ward consists of 12 beds and is operated by a fixed team of two to three supervising senior physicians, 34 specialized nursing staff and eight assistant physicians. The department is serving for all medical and surgical specialities in need of intensive care medicine. Due to logistic reasons some wards are specialized on certain patients groups (e.g. cardiac surgery, stem cell transplantation, neurosurgery) but all teams adhere to the same standard operating procedures and there is frequent exchange of knowledge and patients between the wards. All these wards are operated on the first floor of the university campus.

To improve compliance with the Institute of Healthcare Improvement recommendations for CVL placement [10], we chose a two-step approach. In brief the measures recommended by the institute were a) hand disinfection b) full barrier nursing c) sterile disinfection of the insertion site d) avoidance of the femoral vein and e) strict indication for CVL. Physicians and nurses handling CVL placements were experienced ICU staff and intensively trained on these hygienic procedures. Training started in July 2011 with a department wide kick-off event introducing the study and theoretical backgrounds. Followed by frequent additional reminders during staff meetings on the wards to improve awareness. During the study period the decision whether or not to use the checklist for CVL placement, was made by the individual team. A ward-based team consisted of the assistant physician in charge (responsible for placing the CVL) and the assigned nursing staff (responsible for filling the checklist).

Primary outcome

The frequency of CLABSI in both patient CVL was placed with or without the use of the checklist.

Checklist

An English version of the checklist used in this study can be found in the (Additional file 1). In addition to the bundle components the checklist contained two formal parts for the evaluation of the study. The first part allowed to identify the setting, in detail: catheter site (jugular vs subclavian vs femoral), type (dialysis vs cvl) and urgency of placement (routine vs emergency), whereas the second part was used to document the duration of the procedure and the members of the team performing the procedure.

Catheter types

During the study Certofix® trio-catheters (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) andMARHUKAR™ triple-lumen dialysis-catheters (Covidien™, Neustadt/Donau, Germany) were implanted.

Patients

Data of all patients treated during the study period in one of the ICU wards with a central venous line or a temporary dialysis catheter were analyzed.

Microbiological methods

In patients with a new episode of sepsis [11, 12] and a CVL as potential focus of sepsis, a pair of blood-cultures was taken from a peripheral site, the catheter was explanted and the tip was sent for microbiological testing. The microbiologists who had to evaluate the microbiological results had no information of the patients’ exposure status (checklist used or not used).

Blood cultures (BD Bactec PLUS Aerob/F and Bactec PLUS Anaerobe /F, Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, USA) were incubated in a Bactec FX 40 machine for a total of five days. Material from flagged bottles was streaked onto appropriate agar media and incubated overnight at 37 °C. In parallel, aliquots taken from positive bottles were analyzed by Gram straining. All cultivated microorganisms were further differentiated to the species level by MALDI-ToF mass spectronomy (MALDI Biotyper, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). If necessary, additional methods for species identification according to routine microbiological procedures were applied.

Explanted catheter tips were placed into 5 ml of trypticase soy broth and incubated at 37 °C without shaking. Cultures were visually inspected for growth on a daily basis. Any cultures suspected for microbial growth was streaked onto agar media (Columbia agar containing sheep blood [5% v/v]; McConkey agar; Sabouraud agar, all Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). Microorganisms were further differentiated as outlined above.

The broad use of antimicrobial substances in an ICU setting reduces the sensitivity of blood cultures by about 36% [12,13,14]. Therefore statistical analyses were performed stratified by CLABSI and colonized CVL.

Definition of CLABSI

Corresponding positive microbiological cultures from the catheter tip and a blood culture taken from a peripheral site at the time of the device explantation in a patient with a new onset of sepsis and a CVL as potential sepsis focus [15].

Definition of colonized CVL

A positive microbiological culture from the catheter tip but no corresponding blood culture taken from a peripheral site at the time of the device explantation in a patient with a new onset of sepsis and a CVL as potential sepsis focus [15].

Definition of sepsis

Sepsis was defined according to the international guidelines of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign [16].

Statistical methods

We first computed descriptive statistics like counts, frequencies, and incidences per 1000 catheter days. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P-values were calculated using STATA 12.1.

Results

During the study period 4416 CVL were implanted, 1518 in the checklist group and 2898 in the control group. Patient characteristics in both groups did not differ significantly with respect to age (64.7 ± 14.4 checklist group; 64.8 ± 14.8 control group), male to female ratio (2:1), patient type (surgical, medical), disease severity, or length of ICU stay.

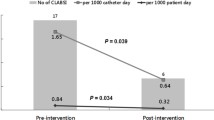

We identified CLABSI in 39 of 1518 patients contributing 11,540 catheter days (3.8 per 1000 catheter days) in the checklist group and in 127 of 2898 patients contributing 21,349 catheter days (5.9 per 1000 catheter days) in the control group (IRR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39–0.82, P = 0.001).

When analyzing colonized CVL, we detected 245 events in 1518 patients (11,540 catheter days; 21.2 per 1000 catheter days) in the checklist group and 776 events in 2898 patients (21,349 catheter days; 36.3 per 1000 catheter days) in the control group (IRR 0.58, 95% CI 0.50–0.68, P < 0.001).

When analyzing the formal aspects of the checklist we identified 267 checklists (17.6%), where at least one of the paragraphs was filled out incompletely, suggesting incomplete compliance. An example for a checklist obviously filled out after the procedure, is available in the (Additional file 2). Nevertheless patients with incomplete checklists had the same reduction in CLABSI as patients with complete checklists. These effects were consistent over all types of ICUs (surgical, medical, neurological); data not shown. In two ICUs patients had a much below average length of stay (< 3 days), with very few newly placed CVLs. Thus here a statistical evaluation of the adherence to the checklist was not possible.

For CLABSI the majority of pathogens isolates were Coagulase negative Staphylococci (CoNS) (79%), Enterococci (5%), S. aureus (3%) and yeasts (7%) in the checklist group and CoNS (76%), Enterococci (7%), S. aureus (6%) and yeast (6%) in the control group. For colonized CVL the distribution was CoNS (63%), Enterococci (18%), S. aureus (3%) and yeasts (5%) in the checklist group and CoNS (61%), Enterococci (17%), S. aureus (4%) and yeasts (5%) in the control group (Fig. 1). When analyzing the CLABSI no significant differences were detected for the site of catheter insertion. Data for the site of insertion were available for n = 1249 catheters; jugular vein (n = 710), subclavian vein (n = 272), femoral vein (n = 267). Catheters placed in the jugular vein had an infection rate of 3.6 per 1000 catheter days compared to 2.7 per 1000 catheter days for all other sites (IRR 1.33, 95% CI 0.60–3.02, P 0.23). Subclavian vein catheters had an infection rate of 1.3 per 1000 catheter days compared to 3.4 per 1000 catheter days for all other sites (IRR 1.04, 95% CI 0.40–2.43, P = 0.45). Femoral vein catheters had an infection rate of 2.0 per 1000 catheter days compared to 7.8 per 1000 catheter days for all other sites (IRR 0.58, 95% CI 0.15–1.67, P = 0.16).

For colonized CVL a protective effect for catheters placed in the subclavian vein was seen (infection rate 5.1 per 1000 catheter days vs 23.5 per 1000 catheter days compared to other sites; IRR 0.52, 95% CI 0.34–0.76, P = 0.0001). When analyzing potential effects of the setting in which the catheter was placed (emergency vs routine) no significant differences were detected for both CLABSI definitions (Fig. 2).

Incidence rate ratios (central vertical line) and 95% confidence intervals (horizontal lines) for various catheter placement sites compared to their comparators. Values for CLABSI are displayed in black, values for colonized CVL in red. Values smaller “1” demonstrate a protective effect, larger “1” a non-protective. Incidence rate ratios for emergency vs routine setting are shown accordingly

Discussion

Introduction of a checklist to improve compliance with hygiene standards for CVL placement in a high volume intensive care setting lead to a significant reduction in CLABSI. Benchmarking with other German hospitals in 2010/11 demonstrated that we ranked in the upper half for CLABSI-incidence in the ICU before introducing the checklist. CLABSI contribute substantially to healthcare cost [2]. The reduction of hospital acquired infections has been found cost effective [17, 18]. According to conservative estimates, the cost of a single CLABSI-episode is about 16,500 US$ [5]. Use of the checklist would thus have resulted in savings of more than 0.9 Mio US$ per year in our study population. Although our study was not designed to demonstrate an effect on mortality it seems a reasonable assumption that the reduction in CLABSI frequency of about 40% would have resulted in a notable improvement of patient safety and outcomes [4, 5]. Thus our study demonstrates that checklists may improve the quality of standard tasks associated with a relatively high proportion of complications. All team members were constantly educated on advantages of checklists as well as the special content and intention of our checklist and the aim of our study in particular. Interestingly, completing the checklist for a standard ICU task had a significant effect on the reduction of CLABSI, even if the checklist was used with incomplete compliance. For example a checklist obviously filled out after the procedure had the same effect on reducing the CLABSI rates as a checklist filled out correctly. One might speculate that the team is focusing on the task if they are aware of the existence of the checklist even if they do not actually use it during the task itself. This may explain why checklists have generally been shown to improve the performance of even highly trained personnel when performing tasks under stress [7]. The Institute of Healthcare Improvement has promoted recommendations for CVL placement to prevent CLABSI [10]. Checklists have been used in various settings (pediatric/surgical ICUs, developed) with generally positive results [19,20,21]. Yet, the use of checklists in highly developed and high volume health care settings has been questioned by recent data from Urbach and colleagues [9]. Failure to demonstrate an advantage of checklists may, however, be due to the endpoint mortality. Differences in mortality may be difficult to demonstrate in a well developed health care system, when rescue measures are in place to deal with potentially hazardous situations like bleeding, shock, or infections. For the prevention of CLABSI the results of our study are in line with findings of other groups [19, 22]. Pronovost and colleagues used a multicenter approach together with the state health system of Michigan. Each participating ICU chose a nurse and a physician as multipliers to distribute the information to the ICU staff, local infection control teams gave monthly feedback about infection rates and measures to improve a safety culture were implemented by periodic team meetings and conferences. The adherence to the infection-control practices was supported by the use of checklist [22]. A similar project reported by DePalo and colleagues from ICUs in Rhode Island highlights the need for the implementation of a local safety culture and the designation of local team leaders and the commitment for ongoing improvement by quality improvement cycles (Engagement, Education, Execute and Evaluate) [19].

In clinical practice the decision whether or not to treat inconclusive microbiological results (colonized CVL) is often difficult, particularly if common skin flora like CoNS, S. aureus or yeasts are isolated [23, 24]. Contamination of the catheter tip during explantation might be one explanation, inoculation during catheter placement with concomitant colonization and infection the other. Most of our patients were critical ill patients and received antibiotic treatment for various reasons (secondary/tertiary peritonitis after abdominal surgery, hematological/oncological patients with sepsis, patients with neurological diseases and hospital acquired pneumonia). Pazin and colleagues showed that the sensitivity of blood cultures drops significantly in a setting like this [13].

In our study the catheter site (jugular/subclavian/femoral) had no effect on the frequency of CALBSI episodes. This is in contrast to older studies and current guidelines [6]. Meta-analyses however [25], suggested that site-specific effects may be due to two studies with extreme results [26, 27]. When excluding these studies from the analysis no effect of the insertion site with regard to infection frequency was observed [25, 28].

On the other hand we could demonstrate a protective effect for the subclavain vein insertion site compared to all other sites in the stratum of colonized CVL, which has also been shown by Parienti [29]. This is most likely explained by the fact that the subclavian route has the longest subcutaneous distance between skin and vessel entry. However regarding this issue our results are difficult to interpret because of unstable estimates due to the relatively low numbers of catheters included in this analysis and a large number of catheters where the site of placement was not documented.

Our study has limitations. First, the lack of randomization in this observational study may have introduced confounding. On the other hand all participants were instructed on the content of the checklist even if the CVL was implanted without using it. This may have resulted in an underestimation of the effect of the intervention. Second, this was a single center experience of a high-volume ICU without specialized “CVL teams”. Thus, while we believe our setting is not unusual, caution is needed when generalizing our findings to other settings.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that a checklist is a valuable tool to prevent CLABSI in ICU patients, may improve patient safety, and subsequently reduce costs for hospital acquired infections. The implementation of checklists for CVL placement should be encouraged even when performed by highly trained ICU personnel.

Abbreviations

- CLABSI:

-

Central line-associated blood stream infection

- CoNS:

-

coagulase negative staphylococci

- CVL:

-

Central venous line

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IRR:

-

Incidence rate ratio

- MALDI-TOF:

-

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization - time of flight

References

Mayr FB, Yende S, Angus DC. Epidemiology of severe sepsis. Virulence. 2014;5:4–11.

Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1198–208.

Malacarne P, Boccalatte D, Acquarolo A, Agostini F, Anghileri A, Giardino M, Giudici D, Langer M, Livigni S, Nascimben E, et al. Epidemiology of nosocomial infection in 125 Italian intensive care units. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76:13–23.

Ziegler MJ, Pellegrini DC, Safdar N. Attributable mortality of central line associated bloodstream infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection. 2015;43:29–36.

(CDC) CfDCaP: Vital signs: central line-associated blood stream infections--United States, 2001, 2008, and 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011, 60:243–248.

O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, Lipsett PA, Masur H, Mermel LA, Pearson ML, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e162–93.

Kerber CW. Changing our culture: adopting the military aviation safety system. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6:332–41.

Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat A-HS, Dellinger EP, Herbosa T, Joseph S, Kibatala PL, Lapitan MCM, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–9.

Urbach DR, Govindarajan A, Saskin R, Wilton AS, Baxter NN. Introduction of surgical safety checklists in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1029–38.

How-to Guide: Prevent Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI) [http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/HowtoGuidePreventCentralLineAssociatedBloodstreamInfection.aspx].

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, et al. Surviving Sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:165–228.

Reinhart K, Brunkhorst FM, Bone HG, Bardutzky J, Dempfle CE, Forst H, Gastmeier P, Gerlach H, Grundling M, John S, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, therapy and follow-up care of sepsis: 1st revision of S-2k guidelines of the German Sepsis society (deutsche Sepsis-Gesellschaft e.V. (DSG)) and the German interdisciplinary Association of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine (deutsche Interdisziplinare Vereinigung fur Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin (DIVI)). Ger Med Sci. 2010;8 Doc14

Pazin GJ, Saul S, Thompson ME. Blood culture positivity: suppression by outpatient antibiotic therapy in patients with bacterial endocarditis. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:263–8.

Cockerill FR, Wilson JW, Vetter EA, Goodman KM, Torgerson CA, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Ilstrup DM, Washington JA, Wilson WR. Optimal testing parameters for blood cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1724–30.

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, Craven DE, Flynn P, O'Grady NP, Raad II, Rijnders BJ, Sherertz RJ, Warren DK. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45.

Bone RC, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:724–6.

Dick AW, Perencevich EN, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, Zwanziger J, Larson EL, Stone PW. A decade of investment in infection prevention: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:4–9.

Mutters R, Mutters NT. Hygiene and infection control measures in intensive care units. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2016;111:261–6.

DePalo VA, McNicoll L, Cornell M, Rocha JM, Adams L, Pronovost PJ. The Rhode Island ICU collaborative: a model for reducing central line-associated bloodstream infection and ventilator-associated pneumonia statewide. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:555–61.

Sacks GD, Diggs BS, Hadjizacharia P, Green D, Salim A, Malinoski DJ. Reducing the rate of catheter-associated bloodstream infections in a surgical intensive care unit using the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Central Line Bundle. Am J Surg. 2014;207:817–23.

Zachariah P, Furuya EY, Edwards J, Dick A, Liu H, Herzig CT, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, Stone PW, Saiman L. Compliance with prevention practices and their association with central line-associated bloodstream infections in neonatal intensive care units. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:847–51.

Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, Cosgrove S, Sexton B, Hyzy R, Welsh R, Roth G, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–32.

Lutz JT, Diener IV, Freiberg K, Zillmann R, Shah-Hosseini K, Seifert H, Berger-Schreck B, Wisplinghoff H. Efficacy of two antiseptic regimens on skin colonization of insertion sites for two different catheter types: a randomized, clinical trial. Infection. 2016;44:707–12.

Luzzati R, Merelli M, Ansaldi F, Rosin C, Azzini A, Cavinato S, Brugnaro P, Vedovelli C, Cattelan A, Marina B, et al. Nosocomial candidemia in patients admitted to medicine wards compared to other wards: a multicentre study. Infection. 2016;44:747–55.

Marik PE, Flemmer M, Harrison W. The risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection with femoral venous catheters as compared to subclavian and internal jugular venous catheters: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2479–85.

Nagashima G, Kikuchi T, Tsuyuzaki H, Kawano R, Tanaka H, Nemoto H, Taguchi K, Ugajin K. To reduce catheter-related bloodstream infections: is the subclavian route better than the jugular route for central venous catheterization? J Infect Chemother. 2006;12:363–5.

Lorente L, Henry C, Martin MM, Jimenez A, Mora ML. Central venous catheter-related infection in a prospective and observational study of 2,595 catheters. Crit Care. 2005;9:R631–5.

LeMaster CH, Schuur JD, Pandya D, Pallin DJ, Silvia J, Yokoe D, Agrawal A, Hou PC. Infection and natural history of emergency department-placed central venous catheters. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:492–7.

Parienti JJ, Mongardon N, Megarbane B, Mira JP, Kalfon P, Gros A, Marque S, Thuong M, Pottier V, Ramakers M, et al. Intravascular complications of central venous catheterization by insertion site. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1220–9.

Acknowledgements

We very much appreciate the help of all participating staff members of the department of intensive care medicine and the department of microbiology for supporting this study.

Authors’ contribution

Study design: DW and CW; data collection: TK, DW and CEB-C; data analysis DW and TK; statistical analysis: SE; drafting the manuscript DW, HR and SK. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by internal grands of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Hamburg Chamber of Physicians (responsible for the Federal State of Hamburg) has waived a formal ethics approval and informed consent for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. The English version of the checklist used for this study. (DOCX 191 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. An example of a checklist, obviously filled out after the procedure. All checks are made with a single dash. The time for the procedure, including preparation, is documented with only 10 min. (PDF 4552 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wichmann, D., Belmar Campos, C.E., Ehrhardt, S. et al. Efficacy of introducing a checklist to reduce central venous line associated bloodstream infections in the ICU caring for adult patients. BMC Infect Dis 18, 267 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3178-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3178-6