Abstract

Background

End stage renal disease (ESRD)/ end stage renal failure (ESRF) is on the rise globally and especially in Singapore. Varicella or chickenpox is not uncommon among adults especially ESRD/ESRF patients. It has been reported to cause complications and even death among immunocompetent adults.

Methods

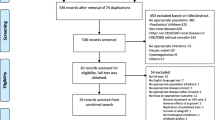

A retrospective data collection on patients with varicella infection and ESRD in Singapore General Hospital (SGH) from the year 2005 to 2016 was performed. Continuous data and categorical data were summarized as median (range) and count (%) respectively. The association of health care utilization (total length of hospital stay, readmission related to varicella, intensive care unit admission) and mortality with complication due to varicella were tested using chi-square and Mann-Whitney test for categorical and continuous outcomes respectively.

Results

Sixty-six patients with ESRD developed varicella during the study period (2005–2016). The case incidence rates for varicella among ESRD ranges from 97 to 267 per 100,000 populations with ESRD yearly. There were 9 deaths (13.6%). Mortality was higher among the ESRD patients with one or more varicella complications compared to patients without complications ((25% vs 7.1%, 95% CI for difference: − 1.1%, 36.9%, p = .063). Likewise, utilisation of intensive or high dependency units were higher among patients with complications compared to those without (20.8% vs 2.4%, 95% CI for difference: 1.6%, 35.3%, p = .012). Length of stay was twice as long in the group with complications compared to patients without (median (IQR) days: 14 (8, 21) vs 7 (5, 14), p = .065), although it did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions

Varicella is associated with high morbidity and significant mortality rate in ESRD patients. Varicella vaccination is recommended for seronegative ESRD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients suffering from chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end stage renal disease (ESRD) / end stage renal failure (ESRF) (both ESRF and ESRD are henceforth referred to as ESRD) are rising worldwide. Incidence rates of ESRD/ESRF is also rising for many developing countries [1]. It was estimated there were 2.6 million people on dialysis in 2010; 93% from high or upper middle-income countries [2]. Worldwide use of renal replacement therapy (RRT) projected to more than double by 2030, with the most rapid increase in Asia [3]. ESRD patients have impaired immune system and are susceptible to serious infections [4]. Patients on haemodialysis (HD) have 14–16 fold increased risk of mortality from pulmonary infections as compared with general population [5].

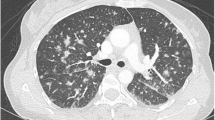

Primary varicella or varicella (henceforth referred to as varicella) which is more commonly known as chickenpox is an acute infectious disease that is caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV), an alpha herpes virus belonging to the Herpesviridae family. Varicella is highly contagious, with secondary household attack rate of over 90% [6]. Varicella zoster virus is transmitted mostly through airborne, and also by direct contact with vesicular fluids. Usually the course of the disease is benign; however it can lead to severe complications and mortality both in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients as well. Clinical illness is mild for all immunocompetent hosts although disease severity increases with age. Adults have 10–20 fold increase in rates of varicella pneumonia and 3 to 17 fold higher rates of hospitalization for varicella or related complications [7]. The list of complications from varicella include pneumonia, pneumonitis, acute obstructive respiratory disease, encephalitis, meningitis, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, Henoch Schonlein purpura, synovitis, Reye’s syndrome, just to name a few. It can also result in secondary bacterial infections that manifest as sepsis, cellulitis, impetigo, abscesses, necrotizing fasciitis, and toxic skin syndrome. Reactivation of dormant varicella-zoster virus within dorsal root ganglia results in herpes zoster (shingles) or less commonly secondary varicella. This can manifests decades after the initial exposure [8].

In Singapore, varicella considered an endemic disease. There were a total of 3987 attendances in polyclinics (health clinics) for chickenpox in 2014 and more than one third of the attendances (1378) were adults over 20 years old [9]. It was reported that the annual incidence rate per 100,000 populations in Singapore was 636.1 in 1989 and 1355.7 in 1996. The annual incidence rates per 100,000 population was between 371 and 665.7 during the period 2002–2007. It is possible that the introduction of varicella vaccine to Singapore in 1996 had contributed to the declining trend [9]. From 1992 to 2011 in Singapore, there were 46 deaths due to varicella (chickenpox), mainly among adults and elderly.

Evidence published to date suggests that varicella vaccination are effective and safe in ESRD and patients on renal replacement therapy [10,11,12,13]. Common adverse effects include redness, pain and swelling at the injection site, fever, headache, myalgia, nausea and itching. There have been several guidelines published internationally recommending varicella vaccination for ESRD or even CKD [14,15,16,17]. The Advisory Committee Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all children and adults without evidence of immunity receive two doses of the vaccine; those who received only one dose of vaccine should receive a second dose [14].

However in Asia region, varicella vaccination in ESRD patients is not widely practiced due to lack of national or regional consensus guidelines. There have been no recommendations made by the local health authorities in Singapore on the role of varicella vaccination among those with ESRD. To our best knowledge, there are no published local data on the risk of VZV infection among ESRD patients. [18]. Therefore this study was done to measure the case incidence rates, mortality and morbidity rates of varicella among ESRD patients in our local context.

Methods

A retrospective data collection on patients with varicella infection and ESRD in Singapore General Hospital (SGH) from the year 2005 to 2016 was performed. Singapore is an island city-state off South-East Asia with dense population of 5.6 million (in 2016) within the 719km2 (277.6 sq. mi.). It has one of the most rapidly ageing population in Asia with increasing patients suffering from chronic diseases. Health care expenditure in Singapore projected to triple from S$4 billion in 2011 to S$12 billion in 2020 with 10,000 additional hospital beds required [19]. SGH is the first and largest hospital in Singapore. SGH treats about half to two-thirds of patients with ESRD and CKD in Singapore [4].

The study period was defined from 1st January 2005 to 31st December 2016. The ethics approval was obtained from SingHealth Centralised Institutional Research Board (CIRB) (Reference: 2016/2780).

The inclusion criteria were patients with ESRD or ESRF or CKD Stage 5 – estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) < 15 mL/min (regardless if the patient was on renal replacement therapy or on conservative management of patient’ kidney failure) that contracted varicella infection during the study period of 2005–2016. Varicella infections included varicella without complication and complications such as pneumonia, varicella pneumonitis, varicella encephalitis, varicella meningitis, and other complications. Exclusion criteria were patients with herpes zoster (secondary varicella infection), varicella without underlying ESRD/ESRF/CKD Stage 5 and patients with ESRD/ESRF/CKD Stage 5 but who did not develop varicella.

Electronic medical records were searched with the both International Classification of Diseases, ICD- 9 and ICD-10 codes [20, 21]. ICD-9 codes for ESRD/ESRF/CKD Stage 5 included these starting with 403.01, 403.11, 403.91, 404.02, 404.03, 04.12, 404.13, 404.92, 404.93, 581.x, 582.x, 583.0–583.7, 585.x, 586.x, 588.0, V42.0, V45.1, and V56.x. For ICD-10, we included codes starting with I12.0, I13.1, N18.5, N18.6, and Z99.2. As for varicella, codes starting with 052.x were used in ICD-9 and codes starting with B01.x were used in ICD-10.

Data was extracted by the department of information technology, SGH. Data was checked manually by three authors independently to ensure accuracy of the extraction. Initial data that does not fulfil the inclusion criteria or that fulfilled the exclusion criteria was excluded.

Data on demographics (age, sex, gender, ethnic group, and occupation), cardiovascular comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease), and details of renal disease (years being diagnosed with ESRD/ESRF, whether patient on renal replacement therapy, and modality of renal replacement therapy) were retrieved. Presence of previous varicella exposure was determined by serology test of positive varicella immunoglobulin G (IgG) during the presentation of varicella infection. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) was tested using Indirect Fluorescent Antibody (IFA) (IFA, Hemagen Diagnostic Incorporation, United States of America, USA) and IgG was tested using Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) (EIA, HUMAN Diagnostics, Germany). Number of end organ complications caused by varicella infection, length of hospital stay (admission), length of intensive care or high dependency units (ICU/HDU) stay, and readmissions were captured as a measure of burden of disease.

All statistical analysis was conducted using the International Business Machine Corporation (IBM) Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0. Continuous data and categorical data were summarized as median (range) and count (%) respectively. The association of health care utilization (total length of hospital stay, readmission related to varicella, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission) and mortality with complication due to varicella were tested using chi-square and Mann-Whitney test for categorical and continuous outcomes respectively. Complication due to varicella was defined as 1 or more of the following complications: varicella encephalitis, varicella meningitis, varicella pneumonitis, hepatitis, varicella keratitis, and other varicella complications.

Results

During the 12 year observation period (2005–2016), a total of 66 patients with ESRD were admitted to SGH for primary varicella infection. Patients had a median age of 53 years and were predominantly male (56.1%), Table 1. Three quarter of the patients were Chinese (77.3%). Most of the patients had existing cardiovascular co-morbidities: hypertension (87.9%), dyslipidaemia (66.7%), diabetes (30.3%), ischaemic heart disease (25.8%), and coronary artery disease (22.7%).

The median duration between diagnosis of ESRD and documented admission for primary varicella infection was 6 years. One patient developed varicella 19 years after being diagnosed with ESRD. Only 19 patients who developed varicella have documentation on prior VZV antibody status (i.e. VZV IgG positive or negative) on medical records during the index admission for varicella infection. Among the 19 patients, 8 (42.1%) were found to be seronegative (negative IgG- class antibodies), Table 1.

More than two-thirds (71%) had dialysis as the mode of renal replacement therapy, Table 1. 23 of the patients had renal transplantation (34.8%). Among the renal transplant recipients, 60.8% still has functioning kidney at the time of study. Among 23 renal transplanted recipients, 2 died (8.7%) during the 12-year review.

The case incidence rates for varicella among ESRD were low; ranging from 97 to 267 per 100,000 population per year. Mortality rate among patients with primary varicella on the background of ESRD was 13.6%. Among the nine patients that died of varicella, two were renal transplant recipients, four were haemodialysis patients, and the remainder three were not on any renal replacement therapy. Two demised patients had varicella encephalitis and pneumonia, two with varicella encephalitis, and two with varicella pneumonia. During the study period, there were 81 reported deaths from varicella without ESRD. 11.1% of the patients who died of varicella had an underlying ESRD.

As for morbidities, 24 (36.4%) patients developed at least one complication from primary varicella (see Fig. 1). These included encephalitis, pneumonia or pneumonitis, and meningitis. 9% of the patients had admission either in the intensive care unit or high dependency unit. 83.3% of the patients had readmission within 30 days from varicella and non-varicella related illnesses. Median length of stay was 10 days. Length of stay was twice as long in the group with complications compared to patients without (Table 2).

Discussion

We found that primary varicella infection resulted in a significant morbidity and mortality among patients with ESRD. Overall mortality rate among this inpatient group of patients was 13.6%. Deaths were higher among patients with one or more system involvement compared to those who had none. As for morbidity, the utilisation of higher degree of care support was evident given that those with one or more organ system involvement had more admissions into the intensive care unit (ICU) and high dependency unit (HDU). Patients with one or more organ system involvement stayed longer in hospital compared to those without complications although this was not significant statistically.

The demographics of our patients with ESRD and varicella was similar to the national demographics [4]. Slightly more than half of the patients were male which is comparable to national data. The predominant race in this group of patients is the Chinese which is comparable to national data; 77.3% vs 65.3–72% [4].

Our mortality rate obtained was consistent with Fehr’s findings (2002) where mortality rates of varicella among renal allograft recipients were 22% after 1990 [22]. Prior to the introduction of acyclovir the overall mortality rates was 34% [22]. One ten year retrospective analysis of renal allograft patients showed that varicella associated with an increased mortality of 13.4% [23]. To our knowledge and review of literature, there were no reports on mortality rates among patients with ESRD on dialysis and ESRD not on renal replacement therapy for direct comparison. Most varicella patients died of multiorgan failure (from hepatitis, encephalitis, pneumonitis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation) [24,25,26,27], and respiratory failure [28].

There was no similar data on case incidence of varicella among ESRD patients obtained from literature. Case incidence of varicella among renal allografts recipients has been reported at 0.84 to 1% [24, 25].

Although the available data for previous immunity (VZV IgG) among the infected patients was small (n = 19), VZV seronegative of 42% is not much different from results from literature. Rodriguez reported eight patients with varicella infection; of whom four (50%) were tested negative for VZV IgG [25]. Similarly, Abad et al. reported a baseline serology of 32 cases with disseminated varicella among renal transplant patients; of which 59.4% were seronegative [29].

At present we have no data on the prevalence of VZV seropositivity among non-varicella infected ESRD patients. Published reports revealed that among candidates or recipients of renal transplant (without varicella); the prevalence of seronegative patients were much lower at 2.1 to 9.8% [12, 13]. The 2010 National Health Survey using residual blood samples from healthy volunteered adults (comorbidities unknown) showed that seroprevalance of varicella antibodies among adults (17–79 years old) in Singapore was around 88% [29]. In view that ESRD patients are at higher risk due to their immunocompromised state, we should aim for a seroprevalance (positive IgG) among ESRD patients that is similar to the 88% among healthy adult community in Singapore [30] or even more in view that their immunocompromised state.

Limitations and future plans

The main limitation of this study was the lack of complete documented data from retrospective study as it is wholly dependent on the thoroughness of the discharge summary which is usually done by the junior doctors. These information included the occupation of the patients, the underlying cause leading to ESRD/ESRF, previous immunity to varicella. The degree of complications and organ system involvement could also be underreported if it was not dedicatedly reported in the diagnosis column by the managing team. We minimised this limitation by a thorough check of both the electronic medical records and discharge codes.

The second limitation is that the data collected was from a single centre study. However, the Singapore General Hospital treats the majority of renal patients in Singapore (up to 65.4%) and our patient demographics was similar to the national demographics for ESRD patients. In future studies, pooling of data from other major centres in Singapore looking after renal patients would give a more comprehensive information of varicella infection among ESRD patients in Singapore.

Cost analysis studies is yet to be done to accurately quantify the full extent of morbidity among this group of patients. Despite having chronic disease of ESRD, most of the patients were still working adults. Admission from varicella definitely indirectly incur major impacts such as absences from work, loss of income, and effect on other family members having need to take time out to take care of patients being hospitalised.

Implications for clinical practice

ESRD patients are immunocompromised, and renal transplantation recipients require immunotherapy agents. Therefore patients with ESRD are highly susceptible for communicable disease. It is not uncommon for the patients to contract primary varicella infection. Once infected, varicella has been proven to be highly lethal disease; more than one in eight will succumbed to fatality from varicella infection. Whilst in other more developed countries, varicella vaccination has been introduced as national immunisation schedule leading increased immunity, this is not so with Singapore. We therefore recommend that screening of previous immunity to be carried out among patients with ESRD, regardless of their status of renal replacement therapy be it for renal transplant or not. Those who have no previous immunity to varicella should be given two doses of live attenuated varicella vaccine.

Family physicians in Singapore treat the largest pool of patients in the country. Advocating vaccinations for example pneumococcal, influenza, and human papillomavirus to the group of patients has always being in the sphere of primary care duties of family physicians. This should be extended to include varicella vaccination to the end stage renal disease patients in view of the significant morbidity and mortality of varicella infection to this group of patients.

Conclusions

In our study, we found that ESRD patients had significant morbidity and mortality associated with primary varicella infection. ESRD patients should be screened for immunity to varicella and those without immunity to varicella considered for varicella vaccination, in accordance to well-established international guidelines.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- EIA:

-

enzyme immunoassay

- ESRD:

-

end stage renal disease

- ESRF:

-

end stage renal failure

- GFR:

-

glomerular filtration rate

- HD:

-

haemodialysis

- HDU:

-

high dependency unit

- IBM:

-

International Business Machine Corporation

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IFA:

-

indirect fluorescent antibody

- IgG:

-

immunoglobulin G

- IgM:

-

immunoglobulin M

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- km2 :

-

kilometre square

- min:

-

minute

- ml:

-

millilitre

- n:

-

number

- p:

-

p-value

- RRT:

-

replacement therapy

- SGH:

-

Singapore General Hospital

- USA:

-

United States of America

- vs:

-

versus

- VZV:

-

varicella zoster virus

References

Wetmore JB, Collins AJ. Global challenges posed by the growth of end-stage renal disease. Ren Replace Ther. 2016;2(1):15.

Garcia-Garcia G, Jha V, Tao Li PK, Garcia-Garcia G, Couser WG, Erk T, et al. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) in disadvantaged populations. Clin Kidney J. 2014;8(1):3–6.

Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, Neal B, Patrice HM, Okpechi I, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1975–82.

National Registry of Disease (NRDO), Singapore Renal Registry Annual Registry Report 1999–2014.

Eleftheriadis T, Antoniadi G, Liakopoulos V, Kartsios C, Stefanidis I. Basic science and dialysis: disturbances of acquired immunity in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2007;20(5):440–51.

Ong A, Goh KT, editors. A guide on infectious diseases of public health importance in Singapore. Communicable Diseases Division, Ministry of Health [and] Communicable Disease Centre, Tan Tock Seng Hospital; 2011.

Brisson M, Edmunds WJ, Gay NJ, Law B, De Serres G. Modelling the impact of immunization on the epidemiology of varicella zoster virus. Epidemiology Infect. 2000;125(3):651–69.

Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, LaGuardia JJ, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella–zoster virus. New Engl J Med. 2000;342(9):635–45.

Ministry of Health, Singapore. Communicable Disease surveillance in Singapore 2014: Ministry of Health 2015.

Leong CK, Leo YS, Ang SP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on adult vaccination in Singapore. Society of Infectious Disease. 2016:P78–9.

Crespo JF, Gorriz JL, Avila A, Sancho A, Gavela E, Cano A, et al. Prevalence of past varicella zoster virus infection in candidates for kidney transplantation: vaccination in seronegative patients. Transplant Proc. 2002;34(1):77.

Geel AL, Landman TS, Kal JA, Van Doomum GJ, Weimar W. Varicella zoster virus serostatus before and after kidney transplantation, and vaccination of adult kidney transplant candidates. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(10):3418–9.

Kho MM, Zuijderwijk JM, van der Eijk AA, de Kuiper R, Boer-Verschragen MJ, Weimar W, et al. Humoral and cellular response after varicella vaccination in VZV IgG seronegative kidney transplant candidates. Vaccine. 2017;35(1):71–6.

The Management of Chronic Kidney Disease Working Group. Va/DoD clinical practice guideline for the Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in primary care. US Department of veterans affairs and department of. Defense. 2014;

Marin M, Guris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-4):1–40.

National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI), "Active Vaccines: Varicella Vaccine,” from Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ONT: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. Available at http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cig-gci/p04-vari-eng.php; last accessed 20 July 2017.

Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, Davies EG, Avery R, Tomblyn M, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;58(3):44–100.

Low LL, Vasanwala FF, Suhail SM. Varicella encephalitis and pneumonia in a patient with end stage renal failure. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13(1):4.

Low LL, Liu N, Wang S, Thumboo J, Ong ME, Lee KH. Predicting 30-day readmissions in an Asian population: building a predictive model by incorporating markers of hospitalization severity. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167413.

World Health Organization, Practice Management Information Corporation. ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision: Clinical Modification. PMIC (Practice Management Information Corporation); 1998. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm (last accessed 31 Jan 2018).

World Health Organization. ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en (last accessed 31 Jan 2018).

Fehr T, Bossart W, Wahl C, Binswanger U. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: four cases and a review of the literature. Transplantation. 2002;73(4):608–11.

Kaul A, Sharma RK, Bhadhuria D, Gupta A, Prasad N. Chickenpox infection after renal transplantation. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5(3):203–6.

Errasti P, Alvarex ML, Gomex G, Lavilla FJ, Garcia N, Ballester B, et al. Chickenpox in four adult transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 1999;31(6):2341–2.

Rodriguez-Moreno A, Sanchez-Fructuoso AI, Calvo N, Ridao N, Conesa J, Marques M, Prats D, Barrientos A. Varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: experience at one center. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(8):2416–8.

Lauzurica R, Bayes B, Frias C, Fontseré N, Hernandez A, Matas L, Jimenez A, Bonet J, Romero R. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(5):1758–9.

Robertson S, Newbigging K, Carman W, Jones G, Isles C. Fulminating varicella despite prophylactic immune globulin and intravenous acyclovir in a renal transplant recipient: should renal patients be vaccinated against VZV before transplantation? Clin Transpl. 2006;20(1):136–8.

Inokuchi R, Nakamura K, Sato H, Shinohara K, Aoki Y, Doi K, et al. Bronchial ulceration as a prognostic indicator for varicella pneumonia: case report and systematic literature review. J Clin Virol. 2013;56(4):360–4.

Abad CL, Razonable RR. α herpes virus infections among renal transplant recipients. Sem Nephrol. 2016;36(5):344–50.

Fatha N, Ang LW, Goh KT. Changing seroprevalence of varicella zoster virus infection in a tropical city state, Singapore. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;22:73–7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sia Guo Long from Department of Information Technology, Singapore General Hospital for extracting the data.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request but restrictions apply to the availability of these data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LSG, FFV and LLL checked the accuracy of the data. OCY drafted the manuscript. SFMC did the statistical analysis. LLL, MK, LSG and FFV participated in the editing of the manuscript. All authors read and confirmed the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics approval was obtained from SingHealth Centralised Institutional Research Board (CIRB Ref: 2016/2780). The need for consent was formally waived by the ethics committee in CIRB.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ong, C., Low, S., Vasanwala, F.F. et al. Incidence and mortality rates of varicella among end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients in Singapore General Hospital, a 12-year review. BMC Infect Dis 18, 118 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3023-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3023-y