Abstract

Background

Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus is a well-defined risk factor for disease in hospitals, which can range from minor skin infections to severe, systemic diseases. However, the generalizability of this finding has not been thoroughly investigated outside of the hospital environment. We aimed to assess the role of S. aureus colonization as a risk factor for disease in the community.

Methods

We performed a meta-analysis of observational studies and searched PubMed for articles published between December 1979 and May 23, 2016. We included cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies that reported quantitative estimates of both S. aureus colonization and disease statuses of all study subjects. We excluded studies on recently hospitalized subjects, long-term care facilities, surgery patients, dialysis patients, hospital staff, S. aureus outbreaks, and livestock-associated infections. Our meta-analysis was performed using random-effects analysis to obtain pooled odds ratios (ORs) to compare the odds of S. aureus disease with respect to S. aureus colonization status.

Results

We identified 3477 citations, of which 12 articles on 6998 subjects met the eligibility criteria. Overall, subjects colonized with S. aureus were more likely to progress to disease than those who were non-colonized: (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.21–2.88, n = 7 studies). We observed a larger effect with methicillin-resistant S. aureus colonization (7.06, 4.60–10.84, n = 7 studies). However, the methicillin-sensitive S. aureus colonization was not associated with greater odds of disease (1.20, 0.69–2.06, n = 4 studies). Heterogeneity was present across studies in all of the subgroups: S. aureus (I2 = 95.0%, χ2 = 120.3, p < 0.001), MRSA (I2 = 92.8%, χ2 = 82.8, p = p < 0.001), and MSSA (I2 = 86.3%, χ2 = 21.8, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

While the majority of papers individually support the assumption that colonization is a risk factor for S. aureus disease in the general population, there is marked heterogeneity between studies and further investigation is needed to identify the major sources of this variance. There is a shortage of literature addressing this topic in the community setting and a need for further research on colonization as a focus for disease prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is an important bacterial pathogen that can cause opportunistic disease in both community and hospital settings. While S. aureus disease has been associated with exposures in hospital environments, many people without any previous history of hospitalization have also developed disease outside of traditional health care settings since the 1990s [1]. Community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) strains have also gradually circulated in health care settings, demonstrating that some clones are not necessarily more frequently found in the original setting where they were first described (i.e., healthcare associated [HA-MRSA] v. CA-MRSA) [2]. Clinical manifestations of community-associated S. aureus disease can include skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) [3]. It is also an important cause of bacteremia, infective endocarditis, pneumonia, bone and joint infections, and other potentially serious diseases, that vary in prevalence depending on geographic area and the socio-demographic characteristics of the populations [4].

In general, symptomatic S. aureus infections begin when the skin or mucosal barrier is broken and the normally commensal bacteria reaches the bloodstream or elsewhere, especially among those asymptomatically carrying S. aureus [5]. The nasal epithelium is the most common location for S. aureus colonization, while carriage on the perineum, axilla, and other skin sites occur less frequently [6, 7]. A recent worldwide review of S. aureus nasal carriage estimated that the average prevalence of nasal colonization in the general population is 24%, with the highest proportions of persons colonized with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) residing in North and South America, respectively [8]. Bacterial pathogenesis is not fully understood, although virulence determinants of particular strains of S. aureus may play a role [5]. The multifactorial nature of staphylococcal carriage, pathogenesis, and host vulnerability has made it difficult to predict the risk of progression to disease from a colonized state.

The relationship between S. aureus colonization and disease has been widely confirmed in healthcare settings. Several systematic reviews have reported that colonization with S. aureus is associated with an increased risk of disease with the organism in hospital patients who undergo surgery, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or intensive care [9,10,11,12,13]. However, this relationship has not been well-described among those without previous exposure to a healthcare setting. More than 3400 studies of S. aureus colonization and disease have been done, but few evaluate the incidence or prevalence of both community-associated colonization and disease on the same individual. If the association between colonization and disease is more adequately investigated in communities as it has been in hospitals, we may gain a better understanding of whether the potential risk of progression to disease in the general population is different when compared to hospitalized populations. This information is important to properly inform disease prevention strategies in the community settings. We performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the strength of the common assumption that S. aureus colonization is a risk factor for symptomatic S. aureus infection in the community setting.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted this meta-analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14]. We searched PubMed to identify papers that reported the prevalence of asymptomatic, community-associated S. aureus colonization and the incidence or prevalence of community-associated S. aureus disease. Each literature search consisted of a variation on the following three categories of search terms: (1) pathogen description, (2) exposure, and (3) outcome (Additional file 1). We used these categories as a structure for various combinations of key terms, expressed as any possible combination of the following: (1) “Staphylococcus aureus,” or “methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus,” or “MRSA,” or “methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus,” or “MSSA,” and (2) also including “colonization,” or “carriage” and (3) “infection”.

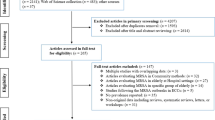

Our literature searches did not place restrictions on publication date, capturing articles published between December 1979 and May 23, 2016, the date of the most recent literature search. We included prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies that reported quantitative estimates of both the S. aureus colonization and disease statuses of all study subjects. Only articles written in English, Spanish, French, or Portuguese were reviewed. To focus the study on S. aureus of community origin, we excluded articles with subjects who underwent surgery or were hospitalized for more than 48 h within one year prior to the start of the study, patients who were concurrently hospitalized, residents of long-term health care facilities, peritoneal or hemodialysis patients, hospital staff, or individuals who have regular contact with livestock (Fig. 1). Additionally, we excluded outbreak studies to minimize the possibility that skin-to-skin transmission or fomite contact led to transmission and/or disease [15].

Data analysis

One researcher (MWK) reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles obtained through the literature review process to select studies that qualified for full-text review according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, in consultation with other authors (BG, RS, CS, LR). In the process of full-text review, the following items were obtained from each study and systematically recorded on a spreadsheet: year of publication, study design, study setting, geographical area, study period, duration of follow-up (if applicable), colonization isolate collection site, method of disease diagnosis, S. aureus type, anatomical site of disease, study population size, and study subject criteria. S. aureus type was described in three categories, based on how it was reported in the original article: (1) all S. aureus, (2) MRSA, and (3) MSSA. Some participants in the MRSA or MSSA categories may also be found in the S. aureus category, but there were no overlaps of cohorts within each of the summary measurements. We assessed the proportion of subjects who were colonized, non-colonized, symptomatically infected, and not symptomatically infected with S. aureus. If joint distributions of colonization and disease could not be ascertained directly from an article, we contacted the authors to inquire about the availability of those data.

Our primary outcome measure was the relative risk of symptomatic S. aureus infection comparing colonized individuals versus non-colonized individuals. We performed separate analyses for general S. aureus, as well as specific types of S. aureus by methicillin susceptibility: MRSA and MSSA. We calculated summary ORs and 95% confidence intervals for each subgroup using an inverse variance weighted random-effects model, employing the chi-square test of homogeneity test statistic and an alpha of 0.05 [16, 17]. We also evaluated consistency of study results with the I2 statistic, which represents the percentage of variation across the studies that is not due to chance [18]. Some studies reported data on multiple S. aureus types and were included in more than one subgroup analysis. In a secondary analysis, we calculated pooled ORs stratified by HIV infection to evaluate whether or not risk of S. aureus disease varied by immune status. We assessed the presence of publication bias in each subgroup by creating funnel plots displaying effect size vs. variance [19]. We further evaluated risk of publication bias with Egger’s test [20]. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether some studies disproportionately affected the overall summary ORs. Data assembly and statistical analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel and STATA V 13.1 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Our literature search identified 3477 unique articles, of which 297 (8.5%) were eligible for full-text evaluation. Of 297 articles included in our full-text review, 285 (96.0% of those eligible) did not satisfy eligibility criteria for inclusion in analysis. Of the articles excluded from full text review, 98 (34.4%) had insufficient data to calculate relative risks of colonization versus disease status and 150 (52.6%) did not meet the inclusion criteria based on study setting or population (Fig. 1). Finally, 12 studies with a total of 6998 study subjects met our inclusion criteria for further analysis [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. These studies consisted of seven prospective cohort studies [21, 23,24,25, 29, 30, 32], two case-control studies [26, 27], and three cross-sectional studies published between 1999 and 2015 (Additional file 2) [22, 28, 31]. Study subjects included 1289 HIV-infected individuals, 552 adult outpatients, 687 pediatric outpatients, 3066 military trainees, 490 prison inmates, and 914 other adults and children in the community. Only two of the 12 studies were done outside of the United States: Taiwan and Italy [28, 31].

Meta-analysis results showed that subjects colonized with S. aureus were more likely to have S. aureus-related disease than those who were non-colonized (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.21–2.88, n = 7 studies; Fig. 2), with a S. aureus colonization prevalence of 34.1% among 2367 subjects. MRSA colonization was associated with greater odds of having disease (7.06, 4.60–10.84, n = 7 studies) compared to MSSA colonization, which was not statistically significant (1.20, 0.69–2.06, n = 4 studies). The prevalence of MRSA colonization was 6.2% among 5417 subjects and the prevalence of MSSA colonization was 26.1% among 912 subjects (Figs. 3 and 4).

The pooled ORs comparing the odds of disease and colonization status were somewhat lower in a subgroup of HIV-infected study participants (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.24–2.74, n = 2 studies) compared to HIV-uninfected participants (2.52, 1.56–4.06, n = 5 studies). However, this difference is not statistically significant and does not provide sufficient evidence for effect measure modification according to previously described methods for comparing two measures of association (Fig. 5) [33]. For studies in the MRSA subgroup, the pooled ORs comparing the odds of disease and colonization status among HIV-infected study participants (8.62, 2.97–25.05, n = 3 studies) and HIV-uninfected populations (6.59, 3.65–11.89, n = 4 studies) were also not significantly different (Fig. 6).

The tests of homogeneity indicated that heterogeneity existed for all subgroups: S. aureus (I2 = 95.0%, χ2 = 120.3, p < 0.001), MRSA (I2 = 92.8%, χ2 = 82.8, p < 0.001), and MSSA (I2 = 86.3%, χ2 = 21.8, p < 0.001). In our assessment of publication bias, Egger’s test did not indicate a significant risk of bias due to the small study effect among studies in each subgroup analysis for S. aureus (bias = 2.26, p = 0.48), MRSA (bias = 3.30, p = 0.26), or MSSA (bias = 2.20, p = 0.49). However, the funnel plots appeared asymmetrical and seemed to display contradictory results (see Additional files 3, 4 and 5). It is possible that publication bias may exist, but our analysis contained too few studies in each subgroup (< 10); thus the Egger’s test and funnel plots cannot confidently assert whether or not publication bias was present. While we did not observe a clear pattern consistent with publication bias, it is important to continue to publish null results in light of the lack of studies available on this subject.

Additionally, we observed several variations in reporting both exposure and outcome. All studies collected nasal swabs from subjects to test for the presence of S. aureus carriage by culture, PCR, or both. Eight studies obtained specimens solely from the nasal cavity, whereas the remaining four studies also tested an additional anatomic site for colonization, including the perineum, axilla, or oropharynx. The method for evaluating disease also differed across studies. Six of the 12 studies relied on laboratory confirmation of disease from clinical isolates, four determined the presence of disease by physician diagnosis without laboratory confirmation, one study collected outcome information from self-reported episodes of disease with medical chart review for a proportion of subjects [24], and one study determined disease by self-report only [22]. Additionally, seven studies assessed molecular concordance between colonizing and infecting isolates by comparing pulse-field type, sequence type, or spa type. These studies estimated that the percentage of S. aureus strains that were concordant ranged from 25 to 100%, but five of the seven studies reported that some isolates were not available for typing (Table 1).

A sensitivity analysis excluding the two articles in which patients self-reported episodes of skin infections [22, 24] during the study period yielded the following results: S. aureus (OR 2.52, 95% CI 0.93–6.83, n = 5 studies), MRSA (8.23, 5.06–13.38, n = 6 studies), and MSSA (1.59, 0.53–4.78, n = 3 studies). The removal of these studies among all subgroup analyses slightly increased the effect sizes, but did not have a disproportionate influence on the overall conclusions for the subgroups.

Discussion

Despite the widespread concern about CA-MRSA [1], this is, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive and systematic evaluation of the risk of S. aureus disease from colonization focused on community-associated infection. While the results of this meta-analysis suggest that the epidemiology of S. aureus may differ across S. aureus types according to their antibiotic susceptibility profiles, it is important to note that we have observed high levels of heterogeneity in this meta-analysis and any interpretation of these results is limited. Still, the majority of the relative measures of association from individual studies were found to be above the null, and supports the overall positive associations observed in this study. We found that individuals colonized with MRSA had higher odds of disease compared to those who were not colonized with MRSA, and seven of seven study effect sizes in this meta-analysis were above the null value despite the presence of heterogeneity. We also observed the same relationship for persons colonized with any kind of S. aureus. The effect sizes included in this subgroup analysis ranged from OR = 0.44 to OR = 37.33 and six of seven studies yielded effect sizes that were both statistically significant and above the null. We did not find conclusive evidence of this when examining MSSA alone, and the two studies that examined both MSSA and MRSA both exhibited lower ORs for MSSA than for MRSA [24, 28]. Still, MRSA strains are not necessarily more virulent than MSSA strains; genetic factors, which may also be associated with resistance status, likely play a more substantial role in bacterial virulence [34].

In previous studies estimating disease incidence only, HIV-positive patients had a higher risk of CA-MRSA disease than the general population [35, 36]. Additionally, a longitudinal study using a series of cultures to test for colonization over time reported that a larger proportion of HIV-infected individuals persistently carried S. aureus compared to HIV-uninfected individuals [37]. Despite these data suggesting that HIV infection may be associated with higher prevalence of colonization and incidence of disease, our findings suggest that the relationship between colonization and disease in the community does not change with different statuses of HIV infection. HIV-infected individuals were not significantly more likely to be symptomatically infected with S. aureus or MRSA than HIV-uninfected individuals if they had also been colonized with S. aureus or MRSA (p > 0.05). This finding is unexpected, as HIV is universally reported to increase the risk of most infectious diseases due to its immunosuppressive effect. It is also important to note that the number of studies representing HIV-infected participants was small for each subgroup: two for S. aureus, three for MRSA, and one for MSSA. More data may be useful to better evaluate the role of immune status in the progression to S. aureus disease.

There are several limitations to this meta-analysis and the studies included in the present analysis, drawing attention to the variation in research practices and definitions across these studies. First, three studies were cross-sectional, thus making it difficult to establish a causal relationship between colonization and disease without confirming that colonization preceded disease. When study designs limit the ability to establish a temporal relationship between colonization and disease, genotyping can detect identical colonizing and infecting staphylococcal isolates, which is commonly used an indicator for endogenous disease [38, 39]. However, none of the three cross-sectional studies included in this meta-analysis compared the strain types of colonizing and infecting isolates. Consequently, we were unable to ascertain whether colonization occurred before or after disease onset. Furthermore, it was not possible to implicate S. aureus as the disease-causing pathogen in six of 12 studies that did not rely on laboratory confirmation of clinical isolates.

Second, methods for evaluating S. aureus colonization varied across studies. Longitudinal studies on nasal colonization have described three types of carriage patterns: persistent, intermittent, and non-carriage, which can only be determined by collecting multiple samples over time [8]. Only four of 12 studies consistently collected more than one swab per individual at different times within the study period. Distinguishing between persistent and intermittent nasal carriage may be important because persistent nasal carriers have been found to have an increased bacterial load with studies suggesting that high bacterial loads increase risk of disease [40]. Moreover, we observed differences in staphylococcal carriage between different anatomical sites across studies. Only four of 12 studies tested more than one area. While the anterior nares is the primary site of colonization, several population studies have found that a significant number of individuals carry S. aureus only in the throat [41,42,43,44]. Thus, throat culture in addition to nares culture may help detect more colonized persons and can be particularly useful when evaluating the risk of S. aureus-related respiratory infections. Children and HIV-infected adults also have an especially high prevalence of carriage in the perineum [45]. Studies that assess colonization only once or at only one anatomical site may lack the sensitivity for accurately categorizing colonization status in study subjects.

Third, the method for diagnosing disease also varied across studies. As discussed, the gold standard for establishing S. aureus as a cause of disease is laboratory culture or PCR of the clinical isolate, supplemented by genotyping. The cause of disease was less clear in the six studies that relied exclusively on physician diagnosis or self-report in the absence of laboratory confirmation. For two studies that used self-report as a method to determine disease, participation in a study in which the investigators periodically request information about recent skin infections could potentially lead to the over-reporting of symptomatic infection episodes due to subjects’ heightened awareness. While culture-confirmed disease is the most reliable way to diagnose staphylococcal disease, one limitation of community-based studies is that it is more challenging and costly to administer laboratory tests compared with hospital-based studies in which these laboratory services are readily available and clinically necessary for patient care.

Of the more than 3000 articles published on colonization and symptomatic infection of S. aureus, only 12 met the inclusion criteria for review and inclusion in our meta-analysis. This highlights the paucity of scientific literature describing the risk of community-onset S. aureus disease in populations without hospital-associated risk factors. We excluded 68 of 135 studies conducted in eligible study populations during the full-text review process due to a lack of complete data to calculate relative measures of association. This may indicate a lack of systematic data collection on colonization status versus disease onset in the same cohort. Future studies seeking to compare the risk of disease between colonized and uncolonized individuals might consider reporting both disease and carriage statuses of all study subjects. Nevertheless, as shown in this meta-analysis, the existing literature suggests that the relationship between colonization and disease still exists apart from traditional hospital-related risk factors.

Given the high prevalence of colonization in the general population (~ 24%) [8], and the role that colonized individuals play in S. aureus transmission [1, 46], colonization status should be considered when establishing public health practices to prevent S. aureus disease especially among high-risk regions and vulnerable subpopulations. Nasal mupirocin treatment is an effective remedy under the assumption that decreasing S. aureus carriage can directly reduce the risk of symptomatic infection. Notably, this method has a lower risk for contributing to the development of antibiotic resistance compared to orally administered antibiotics [47]. However, randomized controlled trials among both United States military trainees and HIV-infected adults have revealed that decolonization by mupirocin made no difference in the incidence of symptomatic infections, and did not did prevent future S. aureus colonization [48]. Even with treatment, infection management, hygiene, and other methods for reducing colonization, preventing disease can sometimes be an ongoing effort.

A study conducted in 2000 comparing the characteristics of 131 community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) cases with 937 hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) cases in Minnesota, found that CA-MRSA cases had a significantly lower median age, were more likely to be non-white, and had lower average household income than HA-MRSA cases [49]. Additionally, clinical indication of skin and soft tissue infection was more common among CA-MRSA cases, while respiratory and urinary tract infections were more common among HA-MRSA cases. Individuals outside of healthcare settings may comprise an important population at risk for developing S. aureus disease, and efforts to prevent the progression from colonization to disease in the community may help to reduce the incidence of serious disease that requires hospitalization. Addressing the issue of community-associated S. aureus infections and the progression from colonization to disease may also require consideration of high-risk settings for infection and transmission [50,51,52], as well as the ethnic and socioeconomic distributions of participants [49, 53, 54].

Conclusion

More rigorous investigation is needed to accurately quantify the risk of progression to disease after colonization due to a shortage of studies on this subject and the observed heterogeneity between studies. While this variance between studies is expected in any pooled analysis, major sources of variance could be mitigated with some aspects of the study design such as standardization of measurements for colonization and laboratory confirmation of disease. Nevertheless, in the absence of classic hospital-associated risk factors for symptomatic infection, colonization was a significant risk factor for disease for both MRSA and S. aureus overall. This finding both supports prior observations that colonization is a risk factor for disease and emphasizes the need for more studies addressing the topic of community-associated S. aureus colonization and disease.

Abbreviations

- CA-MRSA:

-

Community-associated MRSA

- HA-MRSA:

-

Hospital-associated MRSA

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- S. aureus :

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- SSTI:

-

Skin and soft-tissue infection

References

David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(3):616–87. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00081-09.

Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B. Are community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains replacing traditional nosocomial MRSA strains? Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(6):787–94. https://doi.org/10.1086/528716.

Gupta AK, Frcp C, Lyons DCA, Rosen T. New and emerging concepts in managing and preventing community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1226–32.

Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603–61. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00134-14.

Lowy F. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199808203390806.

Williams RE. Healthy carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: its prevalence and importance. Bacteriol Rev. 1963;27(96):56–71.

Yang ES, Tan J, Eells S, Rieg G, Tagudar G, Miller LG. Body site colonization in patients with community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other types of S. aureus skin infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(5):425–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02836.x.

Verhoeven PO, Gagnaire J, Botelho-Nevers E, et al. Detection and clinical relevance of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage: an update. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2014;12(1):75–89. https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.2014.859985.

Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Meta-analysis of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and risk of infection in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(9):2131–41.

Zervou FN, Zacharioudakis IM, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. MRSA colonization and risk of infection in the neonatal and pediatric ICU: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e1015–23. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3413.

Ziakas PD, Anagnostou T, Mylonakis E. The prevalence and significance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization at admission in the general ICU setting: a meta-analysis of published studies. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):433–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a66bb8.

Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10(3):505–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00146-0.

Safdar N, Bradley EA. The risk of infection after nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Med. 2008;121(4):310–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.034.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (reprinted from annals of internal medicine). Phys Ther. 2009;89(9):873–80. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Miller LG, Diep BA. Colonization, fomites, and virulence: rethinking the pathogenesis of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(1537–6591 (Electronic)):752–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/526773.

Dersimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;188:177–88.

Petitti D. Meta-analysis, decision analysis, and cost effective analysis: methods for quantitative synthesis in medicine; 1994.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Light R, Pillemer D. Summing up: the science of reviewing research; 1984.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7129.469.

Ellis MW, Griffith ME, Jorgensen JH, Hospenthal DR, Mende K, Patterson JE. Presence and molecular epidemiology of virulence factors in Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains colonizing and infecting soldiers. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):940–5. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02352-08.

Miller M, Cook HA, Furuya EY, et al. Staphylococcus aureus in the community: colonization versus infection. PLoS One. 2009;4(8) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006708.

Szumowski JD, Wener KM, Gold HS, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization, behavioral risk factors, and skin and soft-tissue infection at an ambulatory clinic serving a large population of HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):118–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/599608.

Fritz SA, Epplin EK, Garbutt J, Storch GA. Skin infection in children colonized with community- associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Inf Secur. 2009;59(6):394–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2009.09.001.SKIN.

Peters PJ, Brooks JT, McAllister SK, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization of the groin and risk for clinical infection among HIV-infected adults. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(4):623–9. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1904.121353.

Miko BA, Befus M, Herzig CT, et al. Epidemiological and biological determinants of Staphylococcus aureus clinical infection in New York state maximum security prisons. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(2):203–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ242.

Maree CL, Eells SJ, Tan J, et al. Risk factors for infection and colonization with community-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Los Angeles County jail: a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(11):1248–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/657067.

Lo W-T, Wang S-R, Tseng M-H, Huang C-F, Chen S-J, Wang C-C. Comparative molecular analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from children with atopic dermatitis and healthy subjects in Taiwan. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(5):1110–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09679.x.

Shet A, Mathema B, Mediavilla JR, et al. Colonization and subsequent skin and soft tissue infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a cohort of otherwise healthy adults infected with HIV type 1. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(1):88–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/599315.

Gordon RJ, Quagliarello B, Cespedes C, et al. A molecular epidemiological analysis of 2 Staphylococcus aureus clonal types colonizing and infecting patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1028–36. https://doi.org/10.1086/428612.

Oliva A, Lichtner M, Mascellino MT, et al. Study of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carriage in a population of HIV-negative migrants and HIV-infected patients attending an outpatient clinic in Rome. Ann Hyg. 2013;25:99–107.

Nguyen MH, Kauffman CA, Goodman RP, et al. Nasal carriage of and infection with Staphylococcus aureus in HIV-infected patients. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(3):221–5. 199902020-00008

Altman DG. Statistics notes: interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):219. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219.

Gordon RJ, Lowy FD. Pathogenesis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(Suppl 5):S350–9. https://doi.org/10.1086/533591.

Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Aroutcheva A, Rice T, Hota B. Community-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and HIV: intersecting epidemics. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(7):979–87. https://doi.org/10.1086/651076.

Crum-Cianflone NF, Burgi AA, Hale BR. Increasing rates of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among HIV-infected persons. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(8):521–6. https://doi.org/10.1258/095646207781439702.

Miller M, Cespedes C, Bhat M, Vavagiakis P, Klein RS, Lowy FD. Incidence and persistence of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in a community sample of HIV-infected and -uninfected drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):343–6. https://doi.org/10.1086/519429.

Toshkova K, Annemuller C, Akineden O, Lammler C. The significance of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus as risk factor for human skin infections. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;202(0378-1097 SB-IM):17–24.

von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(1):11–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200101043440102.

van Belkum A, Melles DC, Nouwen J, et al. Co-evolutionary aspects of human colonisation and infection by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9(1):32–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2008.09.012.

Mertz D, Frei R, Jaussi B, et al. Throat swabs are necessary to reliably detect carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(1537–6591 (Electronic)):475–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-8579(07)70021-3.

Widmer AF, Mertz D, Frei R. Necessity of screening of both the nose and the throat to detect methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients upon admission to an intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(1098-660X (Electronic)):835. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02276-07.

Gustafsson EB, Ringberg H, Johansson PJH. MRSA in children from foreign countries adopted to Swedish families. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(1):105–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00096.x.

Ringberg H, Cathrine Petersson A, Walder M, Hugo Johansson PJ. The throat: an important site for MRSA colonization. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(10):888–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365540600740546.

Peters PJ, Brooks JT, Limbago B, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in HIV-infected outpatients is common and detection is enhanced by groin culture. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139(7):998–1008. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268810002013.

Macal CM, North MJ, Collier N, et al. Modeling the transmission of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a dynamic agent-based simulation. J Transl Med. 2014;12(1):124. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-12-124.

Ammerlaan HSM, Kluytmans JAJW, Wertheim HFL, Nouwen JL, Bonten MJM. Eradication of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(7):922–30. https://doi.org/10.1086/597291.

Weintrob A, Bebu I, Agan B, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled study on decolonization procedures for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among HIV-infected adults. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128071.

Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, et al. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA. 2003;290(22):2976–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.22.2976.

Lu D, Holtom P. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a new player in sports medicine. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2005;4(5):265–70.

Weber JT. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:269–72. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84905258367&partnerID=40&md5=f22f4ece59a25fcff2d0f4ab7b2f363a

Charlebois ED, Perdreau-Remington F, Kreiswirth B, et al. Origins of community strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(1537–6591):47–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/421090.

McMullen KM, Warren DK, Woeltje KF. The changing susceptibilities of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a midwestern hospital: the emergence of “community-associated” MRSA. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(6):454–7.

Elston DM. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.018.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fabio Aguilar-Alves and Binh Diep for their constructive feedback on study scope.

Funding

Ben Greenfield was supported by the SAGE-IGERT Fellowship (US National Science Foundation) for his participation in the design of the research and review of the manuscript. Publication fees were provided by Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

Availability of data and materials

All data used or analyzed in this study are included in published articles (see references [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]) and are available and/or summarized in the additional files for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MWK performed literature search, data extraction, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. BKG participated in the design of the literature search and review, provided input at all stages of manuscript preparation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. RES participated in the execution of the literature search and critically reviewed the manuscript. CMS provided guidance for statistical and meta-analysis methods and critically reviewed the manuscript. LWR provided subject-matter expertise and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Literature Review / Full-Text Review. The “Literature Review” section contains literature search history, key words used, number of journal articles yielded in each search, and the number of journal articles that have passed each step of the selection process according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The “Full-Text Review” section contains all of the information gathered from the selected journal article as it pertained to inclusion into the meta-analysis. (XLS 67 kb)

Additional file 2:

Characteristics of studies selected for inclusion in meta-analysis. This file contains descriptive information on the studies included in the meta-analysis: authors, study design, location, study period, number of subjects, study population, study setting, study subjects, disease types, and S. aureus resistance subgroup. (PDF 420 kb)

Additional file 3:

Funnel Plot – All S. aureus. This funnel plot represents an assessment for the presence of publication bias in studies reporting data on colonization and disease associated with all S. aureus. This figure compares the effect size (log(OR)) to variance (the standard error of log(OR)) for each individual study. However, because there are fewer than 10 studies featured in this example, we cannot reliably distinguish between chance and true publication bias. (PDF 17 kb)

Additional file 4:

Funnel Plot – MRSA. This funnel plot represents an assessment for the presence of publication bias in studies reporting data on colonization and disease associated with MRSA. This figure compares the effect size (log(OR)) to variance (the standard error of log(OR)) for each individual study. However, because there are fewer than 10 studies featured in this example, we cannot reliably distinguish between chance and true publication bias. (PDF 17 kb)

Additional file 5:

Funnel Plot – MSSA. This funnel plot represents an assessment for the presence of publication bias in studies reporting data on colonization and disease associated with MSSA. This figure compares the effect size (log(OR)) to variance (the standard error of log(OR)) for each individual study. However, because there are fewer than 10 studies featured in this example, we cannot reliably distinguish between chance and true publication bias. (PDF 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, M.W., Greenfield, B.K., Snyder, R.E. et al. The association between community-associated Staphylococcus aureus colonization and disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 18, 86 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-2990-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-2990-3