Abstract

Background

Early presentation for HIV care is vital as an initial tread in the UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets. However, late presentation for HIV care (LP) challenges achieving the targets. This study assessed the prevalence, trends, outcomes and risk factorsfor LP.

Methods

A 12 year retrospective cohort study was conducted using electronic medical records extracted from an antiretroviral therapy (ART) clinic at Jimma University Teaching Hospital. LP for children refers to moderate or severe immune-suppression, or WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics. LP for adults refers to CD4 lymphocyte count of < 200 cells/ μl and < 350 cells/μl irrespective of clinical staging, or WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 irrespective of CD4 count at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics. Binary logistic regression was used to identify factors that were associated with LP, and missing data were handled using multiple imputations.

Results

Three hundred ninety-nine children and 4900 adults were enrolled in ART care between 2003 and 15. The prevalence of LP was 57% in children and 66.7% in adults with an overall prevalence of 65.5%, and the 10-year analysis of LP showed upward trends. 57% of dead children, 32% of discontinued children, and 97% of children with immunological failure were late presenters for HIV care. Similarly, 65% of dead adults, 65% of discontinued adults, and 79% of adults with immunological failure presented late for the care. Age between 25- < 50 years (AOR = 0.4,95% CI:0.3–0.6) and 50+ years (AOR = 0.4,95% CI:0.2–0.6), being female (AOR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.03–1.5), having Tb/HIV co-infection (AOR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.09–2.1), having no previous history of HIV testing (AOR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1–1.4), and HIV care enrollment period in 2012 and after (AOR = 0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.9) were the factors associated with LP for Adults. For children, none of the factors were associated with LP.

Conclusions

The prevalence of LP was high in both adults and children. The majority of both children and adults who presented late for HIV care had died and developed immunological failure. Effective programs should be designed and implemented to tackle the gap in timely HIV care engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Joint United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) has developed a 90–90–90 treatment target framework in order to end AIDS globally which aims at 90% of people living with HIV knowing their HIV status, 90% of HIV diagnosed patients receiving sustained treatment, and 90% of those on HIV treatment achieving viral suppression [1]. While diagnosing HIV infection is vital as the initial tread in the 90–9090 targets, diagnosis per se is no longer sufficient [2]. Early diagnosis and access to treatment helps people with HIV to timely get and appropriately use HIV treatment [3] that further reduces the virus load and risk of morbidity and mortality. Nevertheless, late presentation for HIV care (LP) has been recognized as an impediment to meet the above mentioned UNAIDS targets.

LP is the result of being late in HIV diagnosis and/or late in linking with or in accessing HIV care [4]. The definition of LP is disparate and is contextualized using the threshold for ART eligibility [5]. To date, numerous definitions have been used including: i) when the baseline CD4 count is < 200 or < 350 cells/μl and/or with an AIDS defining disease [3, 6, 7], ii) when AIDS defining conditions are diagnosed either before or during the period to an HIV diagnosis [8], iii) when AIDS defining conditions are diagnosed in the subsequent 6 months period to an HIV diagnosis [9], or iv) when AIDS defining conditions are diagnosed 12 months period to an HIV diagnosis [10].

LP is associated with increased risk of HIV transmission [11], ART drug resistance [11], and health care expenses [12]. Additionally, LP has been acknowledged as a challenge for the achievement of the ambitious UNAIDS 90–90-90 targets [13, 14]. For the first 90, high magnitude of late HIV diagnosis reflects that there are a number of people who did not know their HIV status. For the second 90, LP results in poor health outcomes and this interrupts the sustainable uptake of the treatment [13]. Furthermore, LP significantly contributes for pre-ART deaths and, this in turn, reduces the number of HIV diagnosed patients on ART [15]. For example, a study from South Africa reported that ART initiation at the time of first presentation to ART clinic boosted treatment uptake by 36% [16]. For the third 90, LP lowers the number of CD4 cells and increases the number of viral counts, and this causes clinical, immunological or virological failure [14, 17]. Previous studies have shown that late diagnosis appeared to be the main reason for virological failure, and ART initiation at first visit increased viral suppression by 26% [16].

LP has been reported to be a significant problem across the globe. In Europe, overall prevalence of 15–66% has been reported [18, 19]. The magnitude of LP in Asia was very significant (72–83.3%) [20], and in Africa, the overall prevalence has been reported to be between 35 and 65% [21, 22]. Nonetheless, heterogeneity in its measurement limited direct comparisons [23]. In Ethiopia in 2015, there were 39,140 new infections, 768, 040 people living with HIV and 28, 650 HIV/ADS deaths [24]. Universal access to ART in the country was launched in 2005 [25], and to date, the coverage of ART—the percentage of people on ART among those in need of treatment [26]— is 52% [24]. However, the status of timely presentation for HIV care is yet to be assessed. One cross-sectional study from northern part of the country has reported a LP prevalence of 68.8% [27].

Demographic, behavioural and clinical factors contributed for LP [6, 20, 28, 29]. For instance, being female, older age, rural dwellers, alcohol users, ‘Khat’ chewers, cigarette smokers, being diagnosed with sever co-morbidities, perceiving HIV related stigma, having contact with commercial sex workers and being exposed to risky sexual behavior were the factors associated with LP [6, 20, 28, 29]. In Ethiopia, other studies have assessed factors affecting LP [6, 27, 29], and all except one were from the northern part of the country.

However, it is well known that the southwestern part of the nation has different cultural and socioeconomic characteristics. It also has the highest HIV prevalence (6.5%) in the country [30] and may have different LP factors which need to be understood to address HIV in these settings. In addition, for patients who started ART, no study has been conducted to assess the outcome and trends of LP. The prevalence of LP among children has also not been determined. Given the above gaps, and the clinical and public health importance of early HIV diagnosis on timely ART commencement, it is imperative to comprehend the LP situation and recommend effective programs that facilitate early presentation for HIV care in Ethiopia. Furthermore, addressing LP may have a substantial contribution for SDG-3 to have good health and wellbeing, and particularly for SDG-3.3 to end HIV epidemics by 2030. This paper examines the prevalence, trend, outcomes and risk factors of LP among children and adults enrolled for ART in Jimma University Teaching Hospital (JUTH), Southwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

A retrospective cohort study was undertaken using data extracted from the ART clinic at JUTH using patient records from June 2003 to March 2015. Details of the study setting has been described elsewhere [31]. The study population was all HIV patients enrolled for ART care in JUTH.

Data source and procedures

The data were extracted from JUTH electronic medical records (EMR) system called comprehensive care center patient application database (C-PAD) that was in place since 2007. HIV care providers record patient clinical and non-clinical information on paper form, which is then entered into the EMR by data clerks. Two data clerks perform the data entry process to ensure completeness. The International Center for AIDS Care and Support (ICAP) at Colombia University was also delivering technical assistance on the electronic patient level data management, and has been conducting random check up of data completeness. This ensures the accuracy and reliability of the EMR data. Weekly patient summary generated from the EMR system helps to flag patients with conditions that seek follow-up. If baseline CD4 and WHO clinical staging were not recorded, records would be excluded.

Study variables and definitions

The dependent variable was the time when a patient presented for HIV care and was dichotomized as late or early. We defined LP for adults when the baseline CD4 cells count is < 200 cells/μl or < 350 cells/μl (pre-and post-revision of national ART guideline) irrespective of WHO clinical staging, or WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 irrespective of CD4 count at the time of first presentation to an ART clinic [3, 6]. Early presentation for HIV care (EP) is the opposite of LP. LP and EP for children are defined in Table 1. The independent variables included age, sex, marital status, educational status, religion, Tb/HIV co-infection, baseline functional status, history of HIV testing, and HIV care enrollment period. History of previous HIV testing refers to testing (one or more times) for HIV before diagnosis. HIV care enrollment period was dichotomized as enrolled for HIV care in 2003–11, and 2012 and after.

Possible outcomes of LP were ART discontinuation, immunological failure and mortality. ART discontinuation is attributed to lost to follow up (LTFU), defaulting and stopping medication while remaining in care. LTFU was if patients had been on ART treatment and had missed at least three clinical appointments but had not yet been classified as “dead” or “transferred out” (TO). Defaulting was if patients had been on ART treatment and had missed less than three clinical appointments but had not yet been classified as “dead” or “TO”. Stopping medication was definedwhen patients had stopped treatment due to any reason while they have remained in care. TO is the official transferring of the patient to another ART clinic within or outside a catchment area. Immunological failure was defined based on the definitions provided by WHO [32]. Mortality (all cause mortality) is the death of people on ART in the reporting period. Table 1 reports the measurements of LP.

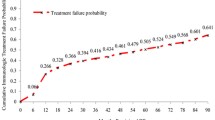

Statistical analyses

Ten year trends (data for years 2003 and 2015 were excluded since their number of months were incomplete) for LP was described by line graphs, and best-fit equation for the trend line was developed. We described the percentage of LP by ART discontinuation, immunological failure and mortality to show the outcomes of LP. The differences between LP and its outcomes were checked using Chi square tests. We used binary logistic regression to identify factors that were associated with LP. Multi-collinearity was checked using variance inflation factor and none was found. In addition, we checked for potential two-way interactions and none was found.

Missing data was treated using multiple imputations (n = 5) assuming missing at random (MAR) pattern [33] and the model was reported with pooled imputed values [34]. We developed an imputation model for adults, however; for children, we did not decide to do the multiple imputations analysis since the missing values for the great majority of the variables were not significant (below 5%). Bivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the presence of crude association and nominate the candidate variables (P < 0.25 was considered) to multiple logistic regression. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered as a cutoff value for statistical significance in the final multiple logistic regression model. We applied Hosmer and Lemeshow test to check goodness of fit of the final model and was found fit (P–value = 0.17). We reported odds ratio and 95% confidence interval to summarize the data. We used Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 for all data analyses.

Results

Of the 8172 patients enrolled for HIV care between 21 June 2003 and 15 March 2015, 5299 (64.8%) patients on ART, the study population for the study, were included. Of the total patients enrolled for ART, 4900 (92.5%) were adults and 399 (7.5%) were children.

Table 2 demonstrates the characteristics of HIV patients on ART. Among the children, 58.1% were aged 5–15 years, 52.4% were males, and 73.9% were Christians. The majority of the children (79.4%) had moderate or severe immune-suppression, and half of the children had baseline WHO clinical stage 3 or 4. A total of 114 (28.6%) children had Tb/HIV co-infection. The median time on ART and estimated survival time, respectively, was 40 and 104.2 (99.8–108.5) months. Among adults, three fifth (59.8%) were females, about half (48.7%) were married and 39% had primary school education. Two fifth (41.6%) of adults had no history of HIV testing. A significant number of adults (73.6%) had baseline CD4 count below 200 cells/mm3, and 54.3% had WHO clinical stage 3 or 4. Over a quarter of adults (27.9%) had Tb/HIV co-infection. Twenty nine (0.9%) adults changed ART regimen during the course of the period. The median time on ART was 49 months, and the median estimated survival time was 121.9 (95%CI: 120.3–123.5) months.

Prevalence, trend and outcomes of LP

The overall prevalence of LP was 65.5%, and females accounted for the majority (64.3%).In total, 215 children (57%) and 1788 adults (66.7%) were late presenters. In the period between 2004 and 2014 the percentage of LP decreased from 83% to 62%. Fig. 1 shows the trend in LP among HIV infected people on ART.

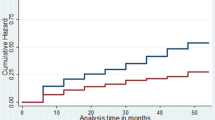

Table 3 reports the outcomes of LP among HIV infected children and adults enrolled in HIV care. Of the children, 57.1% of those who died, 32.3% of those who discontinued care, and 96.9% of those who had immunologic failure were late presenters for HIV care. Of adults, 64.7% of those who died, 65.3% of those who discontinued care, and 78.7% of those who had immunologic failure presented late for the HIV care. The chi-square analysis showed that the difference between LP and, immunologic failure and discontinuation for children was statistically significant. For adults, LP was not statistically different with mortality and ART discontinuation.

Risk factors for LP

Table 4 presents the multiple logistic regression analysis of factors for LP obtained from the complete case analyses. Predictors of LP among adults included being older adult, female, having Tb/HIV co-infection, having no previous history of HIV testing and HIV care enrollment period in 2012 and after. Older adults aged between 25- < 50 years (AOR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.3–0.6) and 50+ years (AOR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.6) were 60% each less likely to present late for HIV care compared to those aged between 15 and 25 years. Females were 20% high likely (AOR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.03–1.5) to present late for HIV care than their comparator. HIV patients with Tb/HIV co-infection were about 2 times at risk of LP (AOR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.09–2.1) than HIV patients alone. In addition, while having no previous history of HIV testing (AOR = 1.2, 95%CI: 1.1–1.4) was a risk factor for LP, HIV care enrollment period in 2012 and after (AOR = 0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–0.9) was a protective factor for LP. No statistically significant predictor was found for LP among children.

Multiple imputations (MI)

To handle the missing data, we applied MI using five imputed data sets. We have presented the results from MI and complete case analyses in Table 4. In estimating factors associated with LP among adults, results were similar in both MI and complete case analyses except for variables Tb/HIV co-infection and previous history of HIV testing were marginally statistically significant in the MI analysis.

Discussion

LP has been described as a sizable obstacle to attaining the UNAIDS 90–90-90 and 95–95-95 targets [7, 14]. This study has shed light on the general problems of late HIV care—magnitude, trend, outcomes and its risk factors. In the current study, the overall prevalence of LP was considerably high (65.5%). Furthermore, the trends of LP had shown persistently elevated prevalence (between 54% and 83%) although a lessening pattern was observed. This finding is consistent with another finding conducted in the country [27]. The prevalence of LP in the current study (65.5%) was lower (72–83.3%) than the prevalence from studies conducted in Asia [20], but higher than the findings from other studies in Africa that reported between 35 and 65% [21, 22]. This implies that LP in Ethiopia is still highly prevalent even after the introduction of universal ART.

The high and persistent LP prevalence may be due to: i) lack of information [35], ii) persistently high level of HIV related stigma [3, 27], iii) low HIV risk perception [27, 35] especially among high risk groups [36], iv) use of traditional treatment [27], v) poor integration between modern medicine and traditional healers, and vi) phasing out of international funding agencies [37]. Additionally, it could also be attributed to poor access to HIV services [37, 38]. For example, only 79% of the total health facilities in Ethiopia deliver HIV counseling and testing services [39]. Primary Health Care principles and scholars describe characteristics of accessible health systems to be approachable, acceptable, available, affordable and appropriate for the target population [40, 41], and thus raising a question whether HIV services are accessible to all HIV patients in Ethiopia. As such, LP issues should be given top priority if Ethiopia is to meet the UNAIDS targets.

Several strategies including the use of technology have been recommended to reduce LP prevalence in developing countries. For example, in collaboration with UNICEF, Amukele and colleagues successfully piloted unmanned aerial systems (drones) for transporting laboratory specimens to reduce late infant diagnosis in Malawi [42]. Other programs such as using mobile text messages [14], home [43] and community-based HIV testing [44, 45] have also been recommended to meet the HIV diagnosis target. Furthermore, encouraging repeat HIV testing [46, 47], HIV testing services delivery by lay workers [48], and self-testing [49] can tackle the substantial gap in HIV diagnosis in low-income countries like Ethiopia. The mandatory HIV testing strategy that has been implemented in China since 2005 for testing at-risk groups such as drug users, inmates, and commercial sex workers along with their clients was found to be an effective strategy to heighten early HIV diagnosis [7] that Ethiopia could consider. Interventions such as lay counselor home visits [50], home visits by peer supporters [51] and informational brochure provision [52] were also important programs in linking patients to ART clinics timely after HIV testing. In addition, the application of rapid or point of care CD4 count technology has shown to enhance the number of eligible patients for ART whereby the frequency of appointments is reduced, and early ART initiation is increased [53].

Compared to the early presenters, great majority of late presenters had died in the current study, and this is similar with findings from other studies conducted elsewhere [54, 55]. It is plausible therefore to argue that late presentation leads to a greater risk of: rapid progression to advanced AIDS stage, compromised immune response, poor treatment response, and finally death [3]. Similarly, consistent with findings of other studies [56, 57], the majority of adults who presented late for care had discontinued and developed immunologic failure. This could be highly possible since late presenters progress easily to advanced AIDS stage, a stage characterized by marked CD4 reduction, multiple comorbidities and poor overall functional status [58, 59]. Subsequently, this leads to poor immune recovery even after treatment initiation, and increases the likelihood of ART toxicity that deters patients to take the treatment regularly [60]. The prevalence of LP among adults was higher than children. This might largely be due to the ‘opt out’ screening programs for pregnant women and delivery of HIV care (testing and treatment) to children born to affected mothers timely [61].

Adult late presenters were more likely to be younger, females, Tb/HIV co-infected, with no history of HIV testing and enrolled to HIV care in 2011 and before. Unlike other studies in Africa [62, 63], older adults were less likely to delay for HIV care than their younger counterparts. We found the finding surprising. HIV disease progresses with time, and it would be expected, that individuals diagnosed with HIV at a higher age would also have advanced disease progression (lower CD4 cell count) because they, on average, had a longer time span between time of infection and time of diagnosis. However, the presence of high HIV related stigma among young adults [64] hampers HIV testing and may be linked to delays in seeking HIV care. In addition, it is also possible that older adults assume a caring responsibility for their family and might realise the need to access HIV care service consistently increase their longevity and to achieve the self-imposed caring responsibility. Unlike in some others [56, 63], females were more likely than males to delay for HIV care. This might be because females have low understanding and comprehensive HIV care knowledge [3]. The high probability of females for LP might also be explained by the fact that 62% of females in care did not have a previous history of HIV testing. Females are also known to use traditional healers more than males, which may lead to commencing the HIV care late [3, 35].HIV related stigma is higher among females than males [65]. It is also known that the health seeking behaviours of females in urban and rural southwest Ethiopia are lower compared to males [66].

The association between Tb/HIV co-infection with increased LP replicate findings from other studies [4]. It has been stated that Tb is inextricably linked with HIV, causes a synergistic combination of illness with HIV, facilitates the progression of HIV disease to advanced stage, and thereby deters patients from linking to care timely [31]. Furthermore, focus has to be given for Tb/HIV co-infection, as Tb remains the highest mortality risk among HIV infected patients [13]. The absence of previous history of HIV testing in association with LP could be linked with poor awareness of the care [3], less access to HIV testing and/or ART clinic [39], high HIV related stigma [67], fear of diagnosis [68] and feeling of wellbeing [69].HIV patients who were enrolled for HIV care in 2012 and after were less likely to present late for HIV care as compared to those enrolled in 2011 and before. This may be attributed to: i) improving awareness to HIV care; ii) improving access and availability to HIV care; and iii) reducing perceived HIV related stigma.

The study has the following limitations. Firstly, data were collected from JUTH, a referral hospital that also receives referrals of patients with advanced stage. Hence, these study participants are not necessarily representative of HIV patients who attend their follow up in health centers or lower health care setups. Secondly, we did not assess the annual proportions of LP across HIV testing strategies (voluntarily counseling and testing, provider initiated HIV testing and counseling (PITC), Outreach or ‘opt out). Previous studies have shown that PITC was not found more effective program for early HIV diagnosis than targeted HIV counseling [7]. Thirdly, the use of conservative definitions for LP is not able to differentiate whether the late presentation is before diagnosis, between diagnosis and first entry to care, and between first entry to care and ART initiation. A gold standard definition for LP among general HIV positive population and special groups such as HIV positive mothers and Tb/HIV co-infected patients for low-income countries is yet to be established. Fourthly, we found no statistically significant predictor for LP among children, and this could be due to small sample size. Finally, the presence of incomplete data may bias the precision of estimates.

However, even with the aforementioned limitations, the study sheds light and underpins the high prevalence of LP. Furthermore, the research assessed outcomes and risk factors for LP across ages, recommended effective programs and benchmarking strategies to tackle LP, and further achieve the ambitious UNAIDS targets.

Conclusions

In summary, three of five HIV infected people presented late for HIV care, and the annual proportions of LP persistently remained high across the 10 year period. The majority of HIV infected children and adults who presented late for care had discontinued, transferred out and developed immunologic failure. Late presenters (adults) were more likely to be younger, females, Tb/HIV co-infected, no history of HIV testing before diagnosis, and enrolled to HIV care before 2012. A large sample size should be considered to assess factors influencing for LP among children. Prioritizing the aforementioned risk factors, tremendous efforts are necessary to curb LP and further achieve the UNAIDS goal. Some of the strategies and programs that help to decline LP are use of innovative technologies, home and community based HIV testing, encouraging repeat and self-HIV testing, mandatory HIV testing and effective linking strategies to care after HIV diagnosis. HIV related stigma should also contextually be tackled since it continues to be a lingering issue among HIV infected people.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- CD4:

-

Cluster of differentiation 4

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- JUTH:

-

Jimma University Teaching Hospital

- LP:

-

Late presentation for HIV care

- PITC:

-

Provider initiated HIV testing and counseling

- Tb:

-

Tuberculosis

- UNAIDS:

-

The Joint United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

UNAIDS: UNAIDS 90–90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic In. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014.

Darling KE, Hachfeld A, Cavassini M, Kirk O, Furrer H, Wandeler G. Late presentation to HIV care despite good access to health services: current epidemiological trends and how to do better. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14348.

Aniley AB, Tadesse Awoke A, Ejigu Gebeye Z, Assefa Andargie K. Factors Associated With Late HIV Diagnosis among Peoples Living with HIV, Northwest Ethiopia: Hospital based Unmatched Case-control Study. J HIV Retrovirus. 2016:2(1).

Gesesew H, Tsehaineh B, Massa D, Tesfay A, Kahsay H, Mwanri L. The prevalence and associated factors for delayed presentation for HIV care among tuberculosis/HIV co-infected patients in Southwest Ethiopia: a retrospective observational cohort. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(1):96.

Fox MP, Rosen S, Geldsetzer P, Barnighausen T, Negussie E, Beanland R. Interventions to improve the rate or timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: meta-analyses of effectiveness. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20888.

Gesesew HA, Fessehaye AT, Birtukan TA. Factors affecting late presentation for HIV/AIDS Care in Southwest Ethiopia: a case control study. Public Health Res. 2013;3(4):98–107.

Cheng W, Tang W, Han Z, Tangthanasup TM, Zhong F, Qin F, Xu H. Late presentation of HIV infection: prevalence, trends, and the role of HIV testing strategies in Guangzhou, China, 2008–2013. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:1631878.

Castilla J, Sobrino P, De La Fuente L, Noguer I, Guerra L, Parras F. Late diagnosis of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: consequences for AIDS incidence. AIDS (London, England). 2002;16(14):1945–51.

Longo B, Pezzotti P, Boros S, Urciuoli R, Rezza G. Increasing proportion of late testers among AIDS cases in Italy, 1996-2002. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):834–41.

Delpierre C, Dray-Spira R, Cuzin L, Marchou B, Massip P, Lang T, Lert F. Correlates of late HIV diagnosis: implications for testing policy. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(5):312–7.

Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Kaslow RA, Bey AK, Vermund SH. Factors associated with delayed initiation of HIV medical care among infected persons attending a southern HIV/AIDS clinic. South Med J. 2006;99(5):472–81.

Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Gebo KA, Network HIVR. The economic burden of late entry into medical Care for Patients with HIV infection. Med Care. 2010;48(12):1071–9.

UNAIDS: The gap report. In. Geneva: Geneva; 2014.

UNAIDS: 90–90-90: On the right track towards the global target. In.; 2016.

Lahuerta M, Ue F, Hoffman S, Elul B, Kulkarni SG, Wu Y, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Remien RH, Sadr WE, Nash D. The problem of late ART initiation in sub-Saharan Africa: a transient aspect of scale-up or a long-term phenomenon? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):359–83.

Rosen S, Maskew M, Fox MP, Nyoni C, Mongwenyana C, Malete G, Sanne I, Bokaba D, Sauls C, Rohr J, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy for HIV at a Patient’s first clinic visit: the RapIT randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002015.

Haskew J, Turner K, Rø G, Ho A, Kimanga D, Sharif S. Stage of HIV presentation at initial clinic visit following a community-based HIV testing campaign in rural Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–7.

COHERE: Late presentation for HIV care across Europe: update from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) study, 2010 to 2013. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2015, 20(47).

Hachfeld A, Ledergerber B, Darling K, Weber R, Calmy A, Battegay M, Sugimoto K, Di Benedetto C, Fux CA, Tarr PE, et al. Reasons for late presentation to HIV care in Switzerland. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(1):20317.

Jeong SJ, Italiano C, Chaiwarith R, Ng OT, Vanar S, Jiamsakul A, Saphonn V, Nguyen KV, Kiertiburanakul S, Lee MP, et al. Late presentation into care of HIV disease and its associated factors in Asia: results of TAHOD. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2016;32(3):255–61.

Geng EH, Hunt PW, Diero LO, Kimaiyo S, Somi GR, Okong P, Bangsberg DR, Bwana MB, Cohen CR, Otieno JA, et al. Trends in the clinical characteristics of HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania between 2002 and 2009. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14

Abebe N, Alemu K, Asfaw T, Abajobir AA. Survival status of hiv positive adults on antiretroviral treatment in Debre Markos referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014;17

Johnson M, Sabin C, Girardi E. Definition and epidemiology of late presentation in Europe. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(Suppl 1):3–8.

Wang H, Wolock TM, Carter A, Nguyen G, Kyu HH, Gakidou E, Hay SI, Mills EJ, Trickey A, Msemburi W, et al. Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980-2015: the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(8):e361–87.

Yared M, Sanders R, Tibebu S, Emmart P. Equity and access to ART in Ethiopia. USA: USAID; 2010.

Mahy M, Tassie JM, Ghys PD, Stover J, Beusenberg M, Akwara P, Souteyrand Y. Estimation of antiretroviral therapy coverage: methodology and trends. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(1):97–102.

Assen A, Molla F, Wondimu A, Abrha S, Melkam W, Tadesse E, Yilma Z, Eticha T, Abrha H, Workneh BD. Late presentation for diagnosis of HIV infection among HIV positive patients in South Tigray zone, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:558.

Nyika H, Mugurungi O, Shambira G, Gombe NT, Bangure D, Mungati M, Tshimanga M. Factors associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Harare City, Zimbabwe, 2015. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):369.

Gelaw YA, Senbete GH, Adane AA, Alene KA. Determinants of late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in southern Tigray zone, Northern Ethiopia: an institution based case-control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12:40.

CSA, ICF. Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2011, vol. 2012. Addis Ababa and Calverton: Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International. p. 17–27.

Gesesew H, Tsehaineh B, Massa D, Tesfay A, Kahsay H, Mwanri L. The role of social determinants on tuberculosis/HIV co-infection mortality in southwest Ethiopia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Research Notes. 2016;9(1):89.

WHO. WHO definitions of clinical, immunological and virological failure for the decision to switch ART regimens. 2013. www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/art/WHO_CG_table_7.15.pdf.

Paul A. Multiple imputation for missing data. A cautionary tale. Sociol Methods Res. 2000;28:301-9.

Donald R. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Harvard University; 1987.

Abaynew Y, Deribew A, Deribe K. Factors associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in south Wollo ZoneEthiopia: a case-control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:8.

Arreola S, Santos GM, Beck J, Sundararaj M, Wilson PA, Hebert P, Makofane K, Do TD, Ayala G. Sexual stigma, criminalization, investment, and access to HIV services among men who have sex with men worldwide. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):227–34.

Rangarajan S, Tram HN, Todd CS, Thinh T, Hung V, Hieu PT, Hanh TM, Chau KM, Lam ND, Hung PT, et al. Risk factors for delayed entrance into care after diagnosis among patients with late-stage HIV disease in southern Vietnam. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e108939.

Tran DA, Shakeshaft A, Ngo AD, Rule J, Wilson DP, Zhang L, Doran C. Structural Barriers to Timely Initiation of Antiretroviral Treatment in Vietnam: Findings from Six Outpatient Clinics. PLoS One. 2012:7(12).

CDC: HIV/AIDS progress in 2014 (update): Ethiopia. In. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: WHO; 2015.

Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:18.

WHO: Declaration of Alma-Ata. In: nternational conference on primary health care Alma-Ata: Declaration of Alma-Ata 1978.

Amukele TK, Sokoll LJ, Pepper D, Howard DP, Street J. Can Unmanned Aerial Systems (Drones) Be Used for the Routine Transport of Chemistry, Hematology, and Coagulation Laboratory Specimens? PloS one. 2015;10(7):e0134020.

Kwame S, Chaila JM, Sian F, Ab S, Sam G, Richard H, Sarah JF, Helen A: Uptake of HIV testing in the HPTN 071 (PopART) trial in Zambia. In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Boston, USA; 2016.

Chamie G, Clark TD, Kabami J, Kadede K, Ssemmondo E, Steinfeld R, Lavoy G, Kwarisiima D, Sang N, Jain V, et al. A hybrid mobile approach for population-wide HIV testing in rural east Africa: an observational study. Lancet Hiv. 2016;3(3):E111–9.

Martinez Perez G, Steele SJ, Govender I, Arellano G, Mkwamba A, Hadebe M, van Cutsem G. Supervised oral HIV self-testing is accurate in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(6):759–67.

Mayer K, Gazzard B, Zuniga JM, Amico KR, Anderson J, Azad Y, Cairns G, Dedes N, Duncombe C, Fidler SJ, et al. Controlling the HIV epidemic with antiretrovirals: IAPAC consensus statement on treatment as prevention and preexposure prophylaxis. J Int Assoc Prov AIDS Care. 2013;12(3):208–16.

Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria M, Smyth C, Kahn JG, Bennett R, Lo YR, Souteyrand Y, Williams B. Highly active antiretroviral treatment as prevention of HIV transmission: review of scientific evidence and update. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(4):298–304.

WHO: Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: what’s new? In. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

Napierala Mavedzenge S, Baggaley R, Corbett EL. A review of self-testing for HIV: research and policy priorities in a new era of HIV prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;57(1):126–38.

Barnabas RV, van Rooyen H, Tumwesigye E, Brantley J, Baeten JM, van Heerden A, Turyamureeba B, Joseph P, Krows M, Thomas KK, et al. Uptake of antiretroviral therapy and male circumcision after community-based HIV testing and strategies for linkage to care versus standard clinic referral: a multisite, open-label, randomised controlled trial in South Africa and Uganda. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(5):e212–20.

Chang LW, Nakigozi G, Billioux VG, Gray RH, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Bollinger RC, Reynolds SJ. Effectiveness of peer support on care engagement and preventive care intervention utilization among pre-antiretroviral therapy, HIV-infected adults in Rakai, Uganda: a randomized trial. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1742–51.

Faal M, Naidoo N, Glencross DK, Venter WD, Osih R. Providing immediate CD4 count results at HIV testing improves ART initiation. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2011;58(3):e54–9.

Govindasamy D, Meghij J, Kebede Negussi E, Clare Baggaley R, Ford N, Kranzer K. Interventions to improve or facilitate linkage to or retention in pre-ART (HIV) care and initiation of ART in low- and middle-income settings--a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19032.

Raffetti E, Postorino MC, Castelli F, Casari S, Castelnuovo F, Maggiolo F, Di Filippo E, D'Avino A, Gori A, Ladisa N, et al. The risk of late or advanced presentation of HIV infected patients is still high, associated factors evolve but impact on overall mortality is vanishing over calendar years: results from the Italian MASTER cohort. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):878.

Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, Monforte AdA, Brockmeyer N, Casabona J, Castagna A, Costagliola D, Dabis F, De wit S et al: Risk Factors And Outcomes For Late Presentation For Hiv-Positive Persons In Europe: Results From The Collaboration Of Observational Hiv Epidemiological Research Europe Study (Cohere). PLoS Med 2013, 10(9):e1001510.

Brown JP, Ngwira B, Tafatatha T, Crampin AC, French N, Koole O. Determinants of time to antiretroviral treatment initiation and subsequent mortality on treatment in a cohort in rural northern Malawi. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13(1):24.

Yombi JC, Jonckheere S, Vincent A, Wilmes D, Vandercam B, Belkhir L. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus HIV diagnosis results of a Belgian single centre. Acta Clin Belg. 2014;69(1):33–9.

Egger M, May M, Chêne G, Phillips AN, Ledergerber B, Dabis F, Costagliola D, D’Arminio Monforte A, de Wolf F, Reiss P, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360

Gesesew H, Gebremedhin A, Demissie TD, Kerie M, Sudhakar M. The association between perceived HIV-related stigma and presentation for HIV/AIDS care in developing countries: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev. Implement. Rep. 2014;12(4):60–8.

Kelley CF, Kitchen CM, Hunt PW, Rodriguez B, Hecht FM, Kitahata M, Crane HM, Willig J, Mugavero M, Saag M, et al. Incomplete peripheral CD4+ cell count restoration in HIV-infected patients receiving long-term antiretroviral treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48(6):787–94.

Mojumdar K, Vajpayee M, Chauhan NK, Mendiratta S. Late presenters to HIV care and treatment, identification of associated risk factors in HIV-1 infected Indian population. BMC Public Health. 2010;10

Kigozi IM, Dobkin LM, Martin JN, Geng EH, Muyindike W, Emenyonu NI, Bangsberg DR, Hahn JA. Late-disease stage at presentation to an HIV clinic in the era of free antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009;52(2):280–9.

Honge BL, Jespersen S, Aunsborg J, Mendes DV, Medina C, da Silva Te D, Laursen AL, Erikstrup C, Weejse C: High prevalence and excess mortality of late presenters among HIV-1, HIV-2 and HIV-1/2 dually infected patients in Guinea-Bissau- a cohort study from West Africa. The Pan African medical journal 2016, 25.

Emlet CA, Brennan DJ, Brennenstuhl S, Rueda S, Hart TA, Rourke SB. The impact of HIV-related stigma on older and younger adults living with HIV disease: does age matter? AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):520–8.

Tiruneh YM, Galarraga O, Genberg B, Wilson IB. Retention in care among HIV-infected adults in Ethiopia, 2005-2011: a mixed-methods study. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156619.

Begashaw B, Tessema F, Gesesew HA. Health care seeking behavior in Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0161014.

Mugoya GC, Ernst K. Gender differences in HIV-related stigma in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):206–13.

Schwarcz S, Richards TA, Frank H, Wenzel C, Hsu LC, Chin CS, Murphy J, Dilley J. Identifying barriers to HIV testing: personal and contextual factors associated with late HIV testing. AIDS Care. 2011;23(7):892–900.

Takah NF, Awungafac G, Aminde LN, Ali I, Ndasi J, Njukeng P. Delayed entry into HIV care after diagnosis in two specialized care and treatment centres in Cameroon: the influence of CD4 count and WHO staging. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:529.

Blake C, Margaret JO, Robert JS, Mary LL, Martha FR. 1994 Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. MMWR. 1994;43(RR-12):1–10.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Jimma University Teaching Hospital for providing access to the data.

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HAG, PW, KW and LM conceived of and designing the study. HAG performed the data collection, data analysis and initial draft manuscript. HAG, PW, KW and LM reviewed the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

HAGis lecturer of Epidemiology in College of Health Science at Jimma University and PhD student in the Discipline of Public Health in Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University. PW is professor and head of public health, and chair of faculty research committee in Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at Flinders University. KW is professor of Epidemiology in College of Health Sciences at Jimma University, director of horn of Africa Resilience Innovation Laboratory, focal person of one health Ethiopia. LM is an associate professor and course coordinator of Master of Health and International Development in the Discipline of Public Health in Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University. All authors are currently staff members in their respective departments.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Social and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee (SBREC) at Flinders University (Project number: 7086) and Institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of Health Sciences at Jimma University (Ref No: RPGC/386/2016). De-identified data were extracted from the database, and its access permission was obtained from JUTH board.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gesesew, H.A., Ward, P., Woldemichael, K. et al. Late presentation for HIV care in Southwest Ethiopia in 2003–2015: prevalence, trend, outcomes and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis 18, 59 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-2971-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-2971-6