Abstract

Background

Many health and social needs can be assessed and met in community settings, where lower-cost, person-centered, preventative and proactive services predominate. This study reports on the development and implementation of a person-centered care model integrating dental, social, and health services for low-income older adults at a community dental clinic co-located within a senior wellness center.

Methods

A digital comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and referral system linking medical, dental, and psychosocial needs by real-time CGA-derived metrics for 996 older adults (age ≥ 60) was implemented in 2016–2018 as part of a continuous quality improvement project. This study aims to describe: 1) the development and content of a new CGA; 2) CGA implementation, workflows, triage, referrals; 3) correlations between CGA domains, and adjusted regression models, assessing associations with self-reported recent hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and clinically-assessed dental urgency.

Results

The multidisciplinary team from the senior wellness and dental centers planned and implemented a CGA that included standard medical history along with validated instruments for functional status, mental health and social determinants, and added oral health. Care navigators employed the CGA with 996 older adults, and made 1139 referrals (dental = 797, care coordination = 163, social work = 90, mental health = 32). CGA dimensions correlated between oral health, medical status, depressive symptoms, isolation, and reduced quality of life (QoL). Pain, medical symptoms, isolation and depressive symptoms were associated with poorer self-reported health, while general health was most strongly correlated with lower depressive symptoms, and higher functional status and QoL. Isolation was the strongest correlate of lower QoL.

Adjusted odds ratios identified social and medical factors associated with recent hospitalization and ED visits. General and oral health were associated with dental urgency. Dental urgency was most strongly associated with general health (AOR = 1.78,95%CI [1.31, 2.43]), dental symptoms (AOR = 2.39,95%CI [1.78, 3.20]), dental pain (AOR = 2.06,95%CI [1.55–2.74]), and difficulty chewing (AOR = 2.80, 95%CI [2.09–3.76]). Dental symptoms were associated with recent ED visits (AOR = 1.61, 95%CI [1.12–2.30]) or hospitalizations (AOR = 1.47, 95%CI [1.04–2.10]).

Conclusion

Community-based inter-professional care is feasible with CGAs that include medical, dental, and social factors. A person-centered care model requires coordination supported by new workflows. Real-time metrics-based triage process provided efficient means for client review and a robust process to surface needs in complex cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The growing population of older Americans presents a significant challenge for the United States’ (U.S.) health system. Many healthcare services remain poorly integrated and are often difficult to access, particularly for lower-income, ambulatory older adults at increased risk for a range of co-occurring medical, dental, and social problems [1,2,3,4]. Further, social services are not routinely screened or referred for in most of the healthcare system, let alone provided or integrated with the delivery of other health services. Clinical care is most costly when provided in certain medical settings, particularly on an inpatient basis in a hospital or in an emergency department (ED). In 2013, older adults over 65 were seen in EDs at rates of 12 per 100 for injury and 36 per 100 for illness reasons [5]. Many health and social needs can be assessed and met in community settings, where lower-cost, person-centered, preventative and proactive services predominate. Here we present a community-based intervention and model of person-centered care that incorporates a new digital Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) to capture, summarize, and communicate medical, dental, functional, and social needs to triage vulnerable older adults to services within a senior wellness center.

CGAs have been used for decades to facilitate whole-person care, establish baseline awareness of patients’ needs, and determine appropriate and coordinated interventions [6]. CGAs are multidimensional and interdisciplinary in nature, and have historically encompassed a broad range of domains, including medical, psychosocial, functional, nutritional, and socioeconomic status [7]. CGAs support coordinated care and have been shown to improve outcomes in many settings by exposing critical needs for simultaneous or staged intervention [7,8,9,10]. However, historically, CGAs have concentrated primarily on medical context and long-term services and supports [7, 11], but they do not always assess social determinants, and none to our knowledge have included oral health. While other oral health assessment tools for older adults do exist (e.g., [12, 13]), many have been designed for use in long-term care residential facilities (for a review, see Chalmers and Pearson [14], and not used frequently in community-settings if they need to be administered by medical or dental providers. The new CGA tool was developed to integrate oral health with community-based medical and wellness services in a unique setting where a dental clinic was co-located with a senior wellness center and clients could be readily referred for clinical oral health services.

There are connections between oral health, chronic medical conditions and overall quality of life, morbidity and mortality have been documented, and comprehensive assessments should include oral health status and needs [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Additionally, psychosocial factors and quality of life are understood as intertwined with physical and oral health status, thus all these domains should be considered in assessments and interventions [21,22,23,24,25]. While a few studies have shown the benefits of an integrated dental and medical model for elder care, most of these models have been implemented in clinical venues rather than as part of person-centered care models in community settings [26,27,28]. The goal in this person-centered model is for the CGA to inform timely, appropriate triage and shared care planning for complex clients in a community-based setting.

Thus, the aims of the present study are threefold; first, we describe the CGA content and its development by a multidisciplinary team, for use in a community-based organization (CBO). Second, we describe the CGA implementation process, including the workflows, triage process, and referral pathways. This process used new digital technology that allowed real-time decision support and metrics-based referrals based on client responses. We show how assessment-derived metrics can help coordinate dental, social, and health services outside the healthcare system, or lead to referral for acute care when needed. Third, we examined cohort assessment data to better understand the prevalence of needs, and correlations between CGA domains. We also estimated adjusted associations between the CGA components and self-reported outcomes (recent hospitalizations and emergency department utilization), as well as clinically-assessed dental urgency.

Methods

Setting and participants

Serving Seniors’ Gary and Mary West Senior Wellness Center (SWC) and the Gary and Mary West Senior Dental Center (SDC) are non-profit CBOs co-located in downtown San Diego, California. Serving over 900 clients daily, the SWC provides physical activity, meals, and social, legal, care-coordination, and mental health services to low-income older adults. The SDC, launched in October 2016, is a four-chair dental clinic designed to focus on collaborative care management for underserved and vulnerable older adults, situated on the second floor of the SWC [29]. This study reports on a convenience sample of 996 new and existing SWC clients who consented for assessment and referral to services between October 1, 2016 and January 1, 2018. Age under 60 was the only exclusion criterion.

Intervention

This Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) project employed Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) [30,31,32,33] and human-centered design approaches [34, 35] to co-develop and pilot a person-centered care model linking health and wellness, dental, and social services by real-time CGA and metrics-based referral in a community-based setting. A multidisciplinary team of social workers, nurses, physicians, dentists, and care navigators met regularly over two years, with input from clients, and co-developed the CGA, with the new oral health assessment, prior to the SDC’s opening.

The clinicians and staff sought to extend, enhance and improve care quality and efficiency at the SWC. The team created and introduced a person-centered model of care to better identify and improve triage processes and care referrals. The addition of dental providers and services altered client care teams at this location and required shifting workflows and adding a pathway to dental care. This team proposed and refined workflows and informatics tools that provided preliminary metrics and rules for referral to support real-time decision-making for referrals and follow-ups. Not all clients that sought dental care were referred directly to dental services. By co-addressing all health and social needs with the CGA, the appropriate first referral could be made.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

The CGA captured clients’ demographics, social factors, healthcare utilization (including recent primary care visits, ED visits and hospitalizations), fall history, nutrition (hunger), health status (including medical conditions, and oral health and mental health status), medications, functional status, and quality of life (Table 1). In addition to standard medical history (conditions, medications, allergies), we included validated instruments for oral health, functional status, mental health and social determinants.

We developed a new Oral Health Assessment (OHA) by drawing from a repository of existing oral health measures from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [11, 36,37,38]. We queried a range of multiple dental symptoms, treatment needs, hygiene behaviors, self-reported oral health status, access barriers, and utilization patterns. There were 14 symptoms on a checklist, that ranged from mild to major concerns. These symptoms included experiencing dry mouth when eating or sleeping, issues with too much or too little saliva, bad breath or taste in mouth, sores in the mouth, bleeding gums, pain and difficulties with tasting, swallowing or chewing. Pain and functional limitations from chewing difficulty were examined separately, as they were considered more severe and urgent problems needing attention. The number of positive responses were summed, and a total score tabulated, with a possible range of 0–14. The symptom variable reflected a count of the total number of symptoms currently experienced by the client, per self-report. We explored different ways to summarize the information from the symptom checklist as there is no standard scoring, and conducted sensitivity analyses and consulted with the dental providers on the care team. Clients in this cohort scored between 0 and 9. We ultimately found that four or more reported symptoms appeared to be the most sensitive threshold, and these individuals were categorized as experiencing many dental symptoms and having greater needs.

Validated instruments for quality of life (Brief Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire, OPQoL-Brief) [39], depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9) [40], and functional status (Vulnerable Elders Survey, VES-13) [41] served as a backbone to query psychosocial status and function. The PHQ-9 and VES-13 are widely validated measures, scored based on standard cutoff values accepted in the literature [39,40,41,42]. PHQ-9 scores greater than 5 were categorized to indicate presence of moderate to high risk for depressive symptoms (possible PHQ-9 full scale range: 0–27). VES-13 scores of 3 or higher were categorized as moderate functional limitation (possible VES-13 full scale range: 0–10). OPQOL-B did not have standard cutoff scoring, and the full scale ranges 13–65. For this study, after sensitivity analyses, we categorized the lowest quartile (those in the sample scoring 26–47) as having low QoL.

Paper versions of the assessment (n = 100) were first tested for time and comprehension. The finalized assessment was translated into Spanish and Mandarin using professional services. Care navigators were SWC staff that were part of the SWC care coordination team, supporting the clinicians. Care navigators conducted the CGAs with clients, reviewed the metrics, and made care referral decisions.

Data analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS Studio 3.6 (SAS Studio Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and R Studio 3.2.5 (R Studio Inc., Boston, Massachusetts). Cohort characteristics and metrics-informed care navigators’ final referral decisions were summarized descriptively. Pearson correlations assessed associations across all metrics (p < .05 for two-tailed test). Odds ratios with confidence intervals were calculated for recent ED visit, hospitalization, and dental urgency models, adjusted for age, sex, race and ethnicity. Recent ED visit and recent hospitalization with an inpatient stay were each defined as within the last 6 months, and dental urgency was based on BSS assessment. Additional covariates in the models were modeled as risk factors, and included demographics (single marital status, homelessness, and living alone), medical/functional status (fair/poor self-rated general health status, falls in last year, presence of pain, medical symptoms and conditions, presence of various health conditions, hearing or memory problems, lack of primary care provider, and VES-13), dental status (more than four dental symptoms, difficulty chewing, toothache), and psychosocial factors (mental health diagnosis, major depressive disorder, suicidal ideation, feeling isolated, quality of life (QoL) based on OPQoL, depressive symptoms based on PHQ-9).

Results

Cohort characteristics

Cohort characteristics are shown in Table 2. Clients’ average age was 72, and 51% were men. Most clients experienced general pain (77%), 51% reported on average 2 or more medical conditions (range = 0–7), 5 prescribed medications (range = 1–20), 2 or more medical symptoms (range = 0–11) and 43% reported 4 or more dental symptoms (range = 0–9). About half (54%) were medically complex (by triage metrics) and reported more than five medications and conditions combined (including diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, and hyperlipidemia). More than two-thirds (68%) had either acute or complex dental disease, and 39% reported toothache. Half (50%) had difficulty chewing, and 14% had difficulty swallowing. Most reported good QoL (OPQoL-B = 50.2, range = 26–65), moderate functional limitation (VES-13 = 1.7, range = 0–10), and low to moderate depressive symptom scores (PHQ-9 = 3.3, range = 0–24). A significant proportion of clients were at high risk for malnutrition and food insecurity (46%). Almost half (49%) reported vision and memory problems (46%). Of those with a significant mental health diagnosis (25%), 41% reported no active treatment. About one-third (36%) reported isolation or loneliness.

Intake and triage

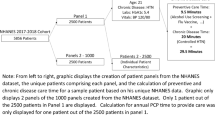

We captured all CGA results in a prototype, shared health record which allowed data intake, metrics conversion and sharing of data with all members of the care teams. The care navigator recorded intake data and reviewed results and metrics for errors. Twenty-two metrics covering health and wellness, dental, and psychosocial needs were displayed as color-coded lights based on high (red), moderate (yellow), and low (green) risk categories (Fig. 1a). On the first pass, the care navigator could view a client list with a summary of four metrics corresponding to services referrals – medical complexity (care coordination), oral health status (dental care), depression risk/suicidality (mental health), and case management (social work) – to quickly locate key patient needs and match with available care (Fig. 1b). The care navigator then made a second pass to consider other pertinent data and metrics in the record and synthesize these for referral decisions.

Overview of new model of person-centered care Fig. 1a) The digital Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) generates biopsychosocial metrics (20 shown from the General Physical Health and Wellness, Mental Health, and Dental categories, teleoapp.com). Metrics results displayed as color-coded lights based on high (red), medium (yellow) and low (green) risk. 1b) The CGA facilitates appropriate referral and assignment to critical health and social services based on triage metrics (1 = Case Management need, 2 = Medical Complexity, 3 = Oral Health Status, 4 = Depression risk) and further investigation by the care navigator. Possible referral pathways are shown. BSS = Basic Screening Survey

Four primary referral metrics were calculated based on composite scores of multiple measures: (a) case management included “homelessness,” “lack of insurance,” “lack of Primary Care Provider (PCP),” and being “low-income” (which was defined as earning ≤199% of the U.S. federal poverty level [FPL]); (b) medical complexity included “number of medical conditions” and “number of medications,” with both defined continuously as counts, with medical conditions categorized as two or more, which was indicative of being a higher risk client with care coordination needs; (c) oral health status was comprised of: “self-rated oral health status,” “missing teeth”, experiencing more than four current dental symptoms (from a list of 14 queried), and functional impairment, including difficulty chewing and food limitation; and (d) depressive symptomology was determined by PHQ-9, with additional weight placed on suicidality (Item 9) for triage purposes.

Clients were referred to services based on the care navigator’s review of extracted metrics and key data such as symptoms, medications, and medical conditions. We designed the metrics to accelerate data review only, and during this pilot phase, referral was ultimately based on the care navigator’s judgement and client’s preference.

Staff used an Acute Clinical Screen (ACS) to assess clients with flagged medical and dental symptoms (e.g., chest pain, jaw pain, shortness of breath, bleeding, fever), and triaged them to 911, urgent medical care, or immediate dental services. Care navigators gave non-acute/well patients a brief take-home questionnaire (Pre-CGA) that included contact and basic medical information (e.g., allergies, medications, problem list, insurance, and medical contacts). Patients completed the Pre-CGA paper forms prior to the first appointment. The care navigator collected and entered clients’ Pre-CGA information, completed the assessment, and referred them to services in the same appointment. Clients with one yellow or red light were typically referred only to that service unless the client requested other services. Clients with 2 or more red lights were referred for simultaneous care, based on their most urgent need. Clients with 1 or more yellow lights were referred based on urgency and navigator’s judgement, and clients with 4 green lights seeking dental care were assigned to dental “usual-care” (described in the next section).

Integrated dental and health workflow

Clients referred to care coordination were assessed by a registered nurse for active medical symptoms, conditions, and establishment of an appropriate medical home. The nurse also provided clients with health education, nursing care, and helped them create personal health action-plans. For clients referred to case management, social workers provided assistance with housing, legal matters, insurance eligibility, and individual and group counseling. Clients referred to mental health received acute assessments (e.g., for suicidality), acute therapy, and medication reconciliation from either the center’s psychiatric nurse or an outside provider.

Non-acute clients referred to dental care participated in a mandatory hour-long oral health education (OHE) course, (developed by Oral Health America; which has now ceased operations, but oral health resources for older adults are still available at https://www.toothwisdom.org/) followed by a Basic Screening Survey (BSS) both administered by a registered dental hygienist (RDH) prior to the client’s first dental appointment. The OHE covered topics on older adults’ oral health and common chronic conditions and provided hygiene demonstrations. We used the BSS, a brief visual exam conducted by RDH, to determine dental urgency and needs as “ground-truth,” compared to self-reported data, and to prioritize scheduling clients for dental care. We followed the standard BSS procedures for screening older adults, using the standard American Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) Toolkit for Older Adults [43]. Based on the BSS, the RDH determines if a client should be seen urgently (immediately/as soon as possible, or within the next 2 weeks), soon (within weeks), or no obvious problem or dental need, and the client can continue their regular care pattern for their next check-up.

Referral outcomes

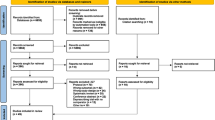

Of 1335 clients engaged, 1012 completed a pre-CGA and 996 completed a CGA without missing responses. Of 1335 clients, 22 reported acute conditions (e.g. active chest pain, fever, severe jaw pain) and completed the ACS. Of these, 9 were referred to PCP/911 and 13 directly to urgent dental care (Table 3). CGA average time to completion was 52 min (range = 34–68). There were no significant differences in response or completion time between English, Spanish, and Mandarin speakers or written versus digital format. Of the clients completing the CGA, 158 declined services or were lost to follow-up and 52 new clients required only nutrition services.

Care navigators made 1210 referrals for 996 clients (dental = 905, care coordination =172, social work = 100, mental health = 33). Of those, 701 needed only a single referral, and 225 received multiple referrals (maximum 4 referrals). The majority of single referrals (683; 98%) were for dental services. Nine clients were referred only to care coordination, 6 to case management and 2 for mental health services. Two hundred twenty clients were referred to dental and at least one more service.

There were no instances of acute medical or psychiatric issues during dental care. Almost all clients referred to dental services completed the OHE and BSS segments, with no-show rates of < 1%. Total no-show rate for dental care was 5.7%. Table 3 summarizes the distribution of services received for each referral (and see Supplemental Figure 1 for a diagram of these referral pathways and outcomes). For dental care, the most common services were preventative (598), periodontics (440) and prosthetics/dentures (217). The most common care coordination services were for medical complexity or management of specific symptoms (59), connection to medical home (46) and enrollment in external services such as specialty dental or medical care (41). Case management services were primarily for health insurance enrollment (32), housing (30) and income assistance (9). Mental health services included linkage to care (11) or counseling or support at Serving Seniors (9). Eight clients were referred to mental health for behavioral or non-compliance issues with the dental center.

Correlations

Correlation analysis of CGA data (Fig. 2) showed significant relationships between the CGA dimensions (all p-values < 0.05). Pain was strongly negatively correlated with general health (− 0.49) and QoL (− 0.32), and positively correlated with depression risk (0.41) and lower functional status (0.43). Self-reported general health was the strongest positive correlate of QoL (0.47) and lower general health was strongly correlated with lower functional status (.53). Number of medical conditions was significantly associated with lower self-reported health (− 0.34) and QoL (− 0.18), correlated with depression (0.26), and strongly correlated with functional limitation (0.35). Medical symptoms were negatively correlated with general heath (− 0.41) and QoL (− 0.26) and associated with depressive symptoms (0.54), low functional status (0.43), and fall risk (0.30). Dental symptoms were negatively correlated with self-rated health (− 0.30) and QoL (− 0.24) and strongly correlated with depressive symptoms (0.43). Dental symptoms were significantly correlated with dental pain (0.54), food limitation (0.21), and difficulty chewing (0.59). Finally, Isolation was associated with medical (0.32) and dental (0.23) symptoms and functional limitation (0.19), strongly correlated with poor general health (− 0.29), pain (0.35) and depressive symptoms (0.43), and was the strongest correlate of low QoL (− 0.50).

Odds ratios

Table 4 summarizes the adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for recent ED visits, hospitalizations, and dental urgency. ED visits were most strongly associated with homelessness (AOR = 3.18, 95% CI [1.59, 6.39]), lack of PCP (AOR = 2.43, 95% CI [1.00, 5.90]), recent falls (AOR = 2.88, 95% CI [2.01, 4.15]) and key specific medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (AOR = 3.05, 95% CI [1.45, 6.44]) and congestive heart failure (CHF) (AOR = 8.86, 95% CI [2.39, 32.80]). Those with moderate to severe depressive symptoms (AOR = 2.36, 95% CI [1.59, 3.50]) or lower QoL (AOR = 1.96, 95% CI [1.32, 2.88]) were approximately 2 times more likely to have had an ED visit within 6 months.

For recent hospitalizations, the most strongly associated with homelessness (AOR = 2.61, 95% CI [1.48, 4.62]), lack of PCP (AOR = 3.04, 95% CI [1.09, 8.51]), poor self-rated general health (AOR = 2.52, 95% CI [1.76, 3.59]), hypertension (AOR = 2.04, 95% CI [1.43, 2.90]), COPD (AOR = 5.05, 95% CI [2.70, 9.42]), CHF (AOR = 6.94, 95% CI [2.61, 18.46]), low functional status (AOR = 2.21, 95% CI [1.53, 3.21]), active depression (AOR = 1.97, 95% CI [1.34, 2.89]), and low QoL (AOR = 2.42, 95% CI [1.67, 3.51]).

Dental urgency was most strongly associated with self-rated general health (AOR = 1.78, 95% CI [1.31, 2.43]), the presence of 4 or more dental symptoms (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI [1.78, 3.20]), the presence of dental pain (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI [1.55–2.74]), and difficulty chewing (AOR = 2.80, 95% CI [2.09–3.76]). Those with more than 4 dental symptoms were also more likely to have had recent ED visits (AOR 1.61, 95% CI [1.12–2.30]) or hospitalizations (AOR 1.47, 95% CI [1.04–2.1]).

Discussion

A broader CGA that includes oral health provides a more complete assessment of health for older adults. This community-based model of person-centered care demonstrated the feasibility of bridging dental, health and social services for older adults through real-time comprehensive assessment and referral. Although the simple triage metrics used in this study could speed data review for those with multiple urgent needs or a combination of moderate and high-risk on certain metrics, further investigation by the care navigator was critical to determine the true urgency and appropriateness of referral. This supports the combination of digital assistance and human assessment, sometimes referred to as “human-technology teamwork” [44] and showcases the need to create multi-disciplinary care teams. The ongoing accrual of referral data provides the opportunity to refine these metrics in future studies.

The prevalence and tight coupling of the CGA dimensions points to the complexity of health among ambulatory older adults. Analysis of the metrics derived from the CGA paints a holistic picture of the cohort and confirmed the significant medical and dental disease burdens and barriers to care faced by clients. This illustrates not just the need for more dental service provision to this population, but the opportunity to integrate with other health and wellness providers (e.g. dentists and social workers). To this point, there have been numerous recent calls for increased integration of services and for comprehensive care to include oral health [45] and to develop team-based approaches. A recent literature review projected a primary care workforce shortage in primary care in community-based settings that is prepared to care for older adults, and that new models that can support collaboration across all caregivers on care teams are needed [46]. Dentists are frequently omitted from these types of care teams and lack sufficient training in geriatrics [47], but there is recognition among dental providers that training support is needed, so that they can care for older adult patients that may transition from being independent to becoming more dependent [48].

This cohort represents an ambulatory population, and a significant number were medically complex and economically vulnerable. Though almost all reported active care from a PCP, more than half had not seen a dentist in the past year, likely due to current differences in health and dental coverage within Medicare and Medicaid, and consistent with the historic U.S. medical-dental divide in health service delivery [49]. Though common social risk factors underlie both medical and dental problems, these dimensions are infrequently assessed together to provide complete information about client needs, and this study demonstrated the value of a CGA that assessed these dimensions together. The current general dental provider workforce lacks geriatric training and are ill-prepared to handle older adults with complex healthcare needs. While there are suggested models for dentists being trained today to include geriatric patient needs [50], there is still a current access problem for community-dwelling, lower-income older adult patients that extends beyond financial barriers. These non-financial barriers to providing person-centered care for older adults remain pervasive throughout the healthcare system, with all types of providers. Challenges also remain with integrating health and social services.

Dental services were a newly offered service at the time of this study and were desired by many clients. Co-locating free and low-cost dental services in a wellness center also eliminated some traditional dental care access barriers, contributing to the very low no-show rate (< 6%) which is far lower than typical for any dental practice [51]. We recognize that this study occurred as part of quality improvement in a unique setting and may not be easily replicable. However, there are still transferrable lessons learned here for building a system that bridges the medical, dental, and social divides. The team-based approach described here grew from collaboration of multi-disciplinary stakeholders identifying the components needed in the CGA and worked together on implementing the workflows. This approach enabled the comprehensive assessment and triage processes to be deployed.

Medical-dental collaborations that include dental providers on primary care teams to enhance access to preventive oral health care have had variable impact [52]. It is challenging to form effective, highly functional multi-disciplinary teams [53], but this mode of person-centered, interprofessional team-based collaborative care is the model of the future. Co-location alone is not sufficient without shared tools that operate in real-time and commitment to integrated workflows to support real collaboration across providers on the team. This approach also positions the team to focus on prevention efforts and wellness, especially after immediate needs are addressed. There is guidance available for creating patient-centered medical homes and caring for medically compromised older adults [54]. However, there are fewer examples and less guidance available for person-centered models of care in community settings.

Our results also add to the limited but growing literature that emphasizes the importance of addressing the oral health status of seniors as part of overall health and well-being. Poor oral health has been associated with functional status limitations among older adults in other studies [55]. Similarly, we found correlations among the CGA health metrics which highlighted key factors associated with QoL, depression, and functional status. Of these, pain, medical symptoms, isolation and depression appeared to be the strongest predictors of poorer self-reported health, while general health was most strongly correlated with lower depression, higher functional status and QoL. Isolation was the strongest correlate of lower QoL. Further, adjusted odds ratios for CGA metrics were strongly associated with key clinical outcomes ranging from emergency department visits and recent hospitalizations to fall risk and dental urgency. Our findings show the potential of CGAs to predict needs, urgency and outcomes in this population, with implications for targeted preventive and more cost-effective efforts.

Conclusions

Community-based inter-professional care is feasible, though it requires collaborative planning and new workflows to implement in-depth client evaluation and metrics-based referrals. A real-time metrics-based triage process that included medical, dental, and social factors in this new CGA provided both an efficient means for client review and a robust process to surface needs in complex cases.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in this study are not publicly available as the datasets contain confidential patient data. The data that support the findings of this study are available from West Health Institute, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a data sharing agreement for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Acute clinical screen

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- ASTDD:

-

American association of state and territorial dental directors

- BSS:

-

Basic screening survey

- CBO:

-

Community based organization

- CBPR:

-

Community-based participatory research

- CGA:

-

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CQI:

-

Continuous quality improvement

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- FPL:

-

Federal poverty level

- OHA:

-

Oral health assessment

- OHE:

-

Oral health education

- OPQoL-Brief:

-

Brief older people’s quality of life questionnaire

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCP:

-

Primary care provider

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient health questionnaire

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RDH:

-

Registered dental hygienist

- SDC:

-

Gary and Mary west senior dental center

- SWC:

-

Serving seniors’ Gary and Mary west senior wellness center

- U.S.:

-

United States

- VES-13:

-

Vulnerable elders survey

References

Araujo de Carvalho I, Epping-Jordan J, Pot AM, Kelley E, Toro N, Thiyagarajan JA, et al. Organizing integrated health-care services to meet older people's needs. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(11):756–63.

Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD). Improving oral health access and services for older adults. 2018. https://www.astdd.org/docs/improving-oral-health-access-and-services-for-older-adults.pdf. Accessed 31 Dec 2018.

Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD). Best practice approach: oral health in the older adult population (age 65 and older). Reno; 2017. p. 29. Available from: http://www.astdd.org. Accessed 31 Dec 2018.

Chavez EM, Wong LM, Subar P, Young DA, Wong A. Dental care for geriatric and special needs populations. Dent Clin N Am. 2018;62(2):245–67.

Albert M, Rui P, McCaig LF. Emergency department visits for injury and illness among adults aged 65 and over: United States, 2012–2013. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017.

Rubenstein LZ, Wieland D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment. Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. 1990:145–92.

Rubenstein LZ, Siu AL, Wieland D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: toward understanding its efficacy. Aging (Milan, Italy). 1989;1(2):87–98.

Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adams J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1032–6.

Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, Tu W, Buttar AB, Stump TE, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298(22):2623–33.

Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P, Burke O, Harwood RH, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:Cd006211.

Atchison KA, Dolan TA. Development of the geriatric oral health assessment index. J Dent Educ. 1990;54(11):680–7.

Chalmers JM, King PL, Spencer AJ, Wright FAC, Carter KD. The oral health assessment tool — validity and reliability. Aust Dent J. 2005;50(3):191–9.

Kayser-Jones J, Bird WF, Paul SM, Long L, Schell ES. An instrument to assess the oral health status of nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 1995;35(6):814–24.

Chalmers JM, Pearson A. A systematic review of oral health assessment by nurses and carers for residents with dementia in residential care facilities. Special Care Dentistry. 2005;25(5):227–33.

Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello AL, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:461–7.

Tavares M, Lindefjeld Calabi KA, San ML. Systemic diseases and oral health. Dent Clin N Am. 2014;58(4):797–814.

McCreary C, Ni RR. Systemic diseases and the elderly. Dental Update. 2010;37(9):604–7.

Otomo-Corgel J, Pucher JJ, Rethman MP, Reynolds MA. State of the science: chronic periodontitis and systemic health. J Evid Based Dental Pract. 2012;12(3 Suppl):20–8.

Mustapha IZ, Debrey S, Oladubu M, Ugarte R. Markers of systemic bacterial exposure in periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jof Periodontol. 2007;78(12):2289–302.

Ettinger RL. The unique oral health needs of an aging population. Dent Clin N Am. 1997;41(4):633–49.

Haikal DSA, Paula AMB, Martins AMEBL, Moreira AN, Ferreira EF. Self-perception of oral health and impact on quality of life among the elderly: a quantitative-qualitative approach. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2011;16(7):3317–29.

Bidinotto AB, Santos CM, Torres LH, de Sousa MD, Hugo FN, Hilgert JB. Change in quality of life and its association with oral health and other factors in community-dwelling elderly adults-a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016.

de Barros Lima Martins AM, Nascimento JE, Souza JG, Sales MM, Jones KM, Ferreira EFE. Associations between oral disorders and the quality of life of older adults in Brazil. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(4):446–57.

Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Litaker MS, Allman RM, Sawyer P, Locher JL, et al. Association between aspects of oral health-related quality of life and body mass index in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1808–16.

Rebelo MA, de Castro PH, Rebelo Vieira JM, Robinson PG, Vettore MV. Low social position, periodontal disease and poor oral health-related quality of life in adults with systemic arterial hypertension. J Periodontol. 2016:1–16.

Marshall S, Cheng B, Northridge ME, Kunzel C, Huang C, Lamster I. Evidence from ElderSmile for diabetes and hypertension. J Calif Dental Assoc. 2015;43(7):379–87.

Marshall SE, Cheng B, Northridge ME, Kunzel C, Huang C, Lamster IB. Integrating oral and general health screening at senior centers for minority elders. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):1022–5.

Metcalf SS, Northridge ME, Widener MJ, Chakraborty B, Marshall SE, Lamster IB. Modeling social dimensions of oral health among older adults in urban environments. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(1 0):63s–73s.

Becerra K, Finlayson TL, Franco A, Asgari P, Pierce I, Forstey M, et al. The Gary and Mary West Senior Dental Center: Whole-person care by community-based service integration. J Calif Dental Assoc. 2019;47(4):225–33.

Tapp H, White L, Steuerwald M, Dulin M. Use of community-based participatory research in primary care to improve healthcare outcomes and disparities in care. J Comparative Effect Res. 2013;2(4):405–19.

Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community based participatory research in health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003.

Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–23.

Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S40–6.

Lin M, Hughes B, Katica M, Dining-Zuber C, Plsek P. Service design and change of systems: human-centered approaches to implementing and spreading service design. Int J Des. 2011;5(2):73–86.

Marchi KS, Fisher-Owens S, Weintraub JA, Yu Z, Braveman PA. Most pregnant women in California do not receive dental care: findings from a population-based study. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(6):831–42.

Amundson G, Solberg LI, Reed M, Martini EM, Carlson R. Paying for quality improvement: compliance with tobacco cessation guidelines. Joint Commission J Qual Patient Saf. 2003;29:59–65.

National Heart L, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). National Institutes of Health (NIH). Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Oral Health Questionnaire. https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/system/files/protocols-manuals/UNLICOMMManual10OralHealthAssessmentv20003302009.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2017.

Slade GD, Spencer A. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Commun Dental Health J. 1994;11(1):3–11.

Bowling A. The psychometric properties of the older people's quality of life questionnaire, compared with the CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2009;2009:298950. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/298950.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(12):1691–9.

Myers JK, Schaffer L. Social stratification and psychiatric practice: a study of an out-patient clinic. Am Sociol Rev. 1954;19:307–10.

American Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) Basic Screening Survey Toolkit for Older Adults. Available at https://www.astdd.org/basic-screening-survey-tool/. Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

Norman D. Design, business models, and human-technology teamwork. Res Technol Manag. 2017;60(1):26–30.

Lee JS, Somerman MJ. The importance of oral health in comprehensive health care. J Am Med Assoc. 2018;320(4):339–40.

Flaherty E, Bartels SJ. Addressing the community-based geriatric healthcare workforce shortage by leveraging the potential of interprofessional teams. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S400–S8.

Thompson L, Jiang T, Savageau JA, Silk H, Riedy CA. An assessment of oral health training among geriatric fellowship programs: a national survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(5):1079–84.

Ghezzi E, Fisher MM. Strategies for oral health care practitioners to manage older adults through care-setting transitions. J Calif Dental Assoc. 2019;47(4):235–46.

Mertz EA. The dental–medical divide. Health Aff. 2016;35(12):2168–75.

Atchison KA, Glicken AD, Haber J. Developing an interprofessional oral health education system that meets the needs of older adults. J Calif Dental Assoc. 2019;47(4):247–56.

Dantas LF, Fleck JL, Cyrino Oliveira FL, Hamacher S. No-shows in appointment scheduling- a systematic literature review. Health Policy. 2018;122(4):412–21.

Atchison KA, Weintraub JA, Rozier RG. Bridging the dental-medical divide: case studies integrating oral health care and primary health care. J Am Dental Assoc. 2018;149(10):850–8.

Harnagea H, Couturier Y, Shrivastava R, Girard F, Lamothe L, Bedos CP, et al. Barriers and facilitators in the integration of oral health into primary care: a scoping review. Br Med J Open. 2017;7(9):e016078.

Patient-centered medical homes and the care of older adults. 2019. Available at: https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/PCMH_Roadmap2016.pdf. Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

Zhang W, Wu YY, Wu B. Does oral health predict functional status in late life? Findings from a national sample. J Aging Health. 2018;30(6):924–44.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all clients, staff, and clinical directors who consented to participate in this program, especially Paul Downey, CEO of Serving Seniors, which runs the Gary and Mary West Senior Wellness Center that houses the Gary and Mary West Senior Dental Center; Vyan Nguyen, Program Officer; and John Little, CFO at the Gary and Mary West Foundation (GMWF). We would also like to thank Shelley Lyford, CEO and President of the GMWF and West Health.

Funding

This work was supported by the Gary and Mary West Foundation, and the Gary and Mary West Health Institute. Gary and Mary West Health Institute (WHI: https://www.westhealth.org/what-we-do/research/) is a medical research institute that utilized existing WHI staff and consultants who analyzed the data. Study team members all contributed to study design, interpretation of results, writing and reviewing the manuscript, and deciding to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EAS, PD, KB conceived the study. EAS, PA, IP, TF, and GN, designed the statistical analysis plan. PA and IP carried out the analysis. EAS, PA, and TF drafted and finalized the paper. JG, MF and CO helped with care navigation and daily operations of the Gary and Mary West Senior Wellness Center. ZA provided insight in the design and implementation phase. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Routinely collected, retrospective, de-identified data were used for this analysis, with a data sharing agreement approved by Gary and Mary West Senior Wellness and Dental Centers and Gary and Mary West Health Institute. Data were analyzed as part of a continuous quality improvement (CQI) initiative approved by the both centers. This study meets the exemption criteria set out by the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB). No further ethics approval was required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Figure 1.

Referral pathways and outcomes. For 1335 clients screened, 1012 completed a pre-CGA and 1000 completed a CGA. For these clients, 901 dental referrals were made for services including restorative, periodontics, dentures, oral surgery and endodontics. One hundred seventy-two referrals were made for medical care-coordination, 90 for case management/social work and 32 for mental health.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aronoff-Spencer, E., Asgari, P., Finlayson, T.L. et al. A comprehensive assessment for community-based, person-centered care for older adults. BMC Geriatr 20, 193 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1502-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1502-7