Abstract

Background

Many home-dwelling elderly use medical compression stockings to prevent venous insufficiency, deep venous thrombosis, painful legs and leg ulcers. Assisting users with applying and removing compression stockings demands resources from the home based health services, but the effects are uncertain. This systematic review aims to summarize the effects of preventive use of medical compression stockings for patients with chronic venous insufficiency and swollen legs.

Methods

We conducted a search in six databases (Epistemonikos, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL and CINAHL) in March 2018. Randomized controlled trials evaluating the preventive effects of European standard compression stockings class 3 or 2 for elderly with chronic venous insufficiency and swollen legs were included. Primary outcomes were thrombosis, leg ulcers and mobility. Secondary outcomes were other health related outcomes, e.g. pain, compliance.

We assessed risk of bias in the included studies and used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool for evaluating the overall quality of evidence.

Results

Five randomized controlled trials met the inclusion criteria. Comparing compression stockings class 2 to class 1, meta-analysis showed a reduction in leg ulcer recurrence at 12 months (RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.88). The quality of evidence was assessed as moderate by GRADE. One study (100 participants) did not detect a difference between compression stockings class 3 versus class 2 on ulcer recurrence after six months (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.20 to 2.03). In another study, patients wearing class 3 compression stockings had lower recurrence risk compared with patients without stockings (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.76) at six months and (RR 0.43; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.69) at 12 months. We found no difference between class 2 and class 1 stockings on subjective symptoms of chronic venous insufficiency or outcomes of vein thrombosis or mobility.

Conclusion

Compression stockings class 2 probably reduce the risk of leg ulcer recurrence compared to compression stockings class 1. It is uncertain whether the use of stockings with higher compression grades is associated with a further risk reduction. More randomized controlled trials on vein thrombosis and mobility are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic venous insufficiency refers to a condition with impaired blood flow in the deep leg veins, and is usually caused by inadequate venous valves. The condition is characterized by symptoms like oedema, skin changes, fatigue, leg pain and a sensation of heaviness in the leg, and can be diagnosed by using ultrasound techniques to detect venous reflux and pooling of blood in deep leg veins [1]. Venous insufficiency may develop into chronic leg ulcer and deep vein thrombosis. Venous thrombosis may damage the valves, and symptoms and signs of chronic venous insufficiency following a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) are called post-thrombotic syndrome [2]. The Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology (CEAP) classification is an accepted standard for classifying chronic venous disorders. The chronic venous disorders are classified from C0 to C6 based on the severity of venous symptoms [1]. The prevalence of venous insufficiency varies considerably between genders, ethnic backgrounds and age groups [3]. A German cross-sectional study from 2008 included more than 3000 people aged 18 to 79 years, and estimated the overall prevalence of venous insufficiency to 31% [4]. The risk of venous insufficiency increases with age [5].

Physical activity, smoking cessation, weight reduction, leg elevation, anticoagulant drugs and medical compression stockings may reduce symptoms and prevent progress of chronic venous insufficiency [6]. External compression, such as medical compression stockings, may reduce oedema and swelling, and improve microcirculation [7]. Medical compression stockings reach the knee or the hip and usually exert a pressure of 20 to 40 mmHg. Different standards exist, but according to the European standard, compression stockings are categorised into four classes [8]. Class 1 stockings exert pressures below 20 mmHg and are used to prevent oedema. Class 2 stockings exert pressures between 20 and 30 mmHg and are used in the prevention of venous insufficiency and varicose veins. Class 3 stockings result in high compressions between 30 and 40 mmHg and are used for chronic venous insufficiency, whereas class 4 stockings exert very high compression above 40 mmHg and are primarily used in the treatment of lymphoedema.

Two studies [9, 10] support the use of compression stockings in the treatment of chronic venous disease in patients under 70 years old, whereas the effectiveness is not known in older populations. Systematic reviews about post-thrombotic syndrome [11,12,13,14] and pain [11] in patients with deep venous thrombosis show uncertain effects. Systematic reviews published in 2013 and 2014 [15, 16] question the effects of preventive use of compression stockings for patients with venous insufficiency, but a preliminary search showed that these systematic reviews were no longer up to date. Elderly patients with chronic venous insufficiency and multimorbidity are of particular interest because they frequently need assistance from home care personnel to administer compression stockings. In this work, we undertake an updated systematic review to investigate the preventive effects of medical compression stockings for elderly patients with chronic venous insufficiency and swollen legs.

Methods

This systematic review follows the recommendations of the Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions [17]. The protocol of this systematic review was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with registration number CRD42018092944.

Search methodology

An information specialist (HS) planned and performed a systematic search in the following databases: Epistemonikos, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL and CINAHL in March 2018. We used a combination of subject headings and text words for venous insufficiency and compression stockings. In addition, searches were made in WHO International Clinical Trials Registry and ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing studies in August 2018. The search strategies were adapted to each database as presented in Additional file 1.

Study selection, data extraction and analysis

We included systematic reviews (SRs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) according to the following criteria: (a) study population of elderly (≥70 years) with venous insufficiency and swollen legs without recent (≤ 2 years) deep vein thrombosis; (b) evaluating the preventive effects of European standard compression stockings class 2 or 3; (c) compared to a different class of compression stockings, other interventions to promote venous backflow or no intervention; (d) assessed on thrombosis, leg ulcer and mobility (primary outcomes) or other health related outcomes such as pain, discomfort, quality of life or post-thrombotic syndrome (secondary outcomes). Compliance was not defined as an outcome in the original protocol, but following feedback, we included compliance as a secondary outcome post hoc.

Two reviewers independently assessed the titles and abstracts of records identified by the search. Records appearing to meet the inclusion criteria and those with insufficient details were obtained in full text. Two reviewers independently assessed the full text publications according to a pre-defined inclusion form. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

The first author (KTD) described the included trials with regard to population, intervention, comparison, outcome and main results in tables. Another reviewer (HTM) checked the extracted information. Two reviewers (KTD, HTM) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Risk of Bias assessment tool [17].

We conducted meta-analysis in Review Manager (RevMan5.3) software [18], when studies were sufficiently similar in terms of design, population, interventions and outcomes. We calculated relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes, both with 95% confidence interval (CI). We used a random effects model to account for pooling effects due to the clinical heterogeneity of the included studies. Double-data entries were performed. We planned to do subgroup analysis based on population and degree of compression, but due to the small number of studies, this was not feasible.

We assessed the quality of the evidence by using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [19]. The assessment involves within-study risk of bias, directness of evidence, inconsistency of effect estimates (heterogeneity), precision of effect estimate and risk of publication bias. The GRADE assessment indicates the extent to which we can have confidence in the effect estimate. Confidence of the effect estimates were described as high, moderate, low and very low (Table 1).

Results

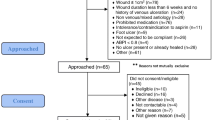

The result of the study selection is shown in Fig. 1. The search yielded 1027 unique references, and 47 references were retrieved and reviewed in full text. Five randomized controlled trials were included. We found no relevant ongoing studies. The studies were published between 1997 and 2013 and included a total of 684 participants with chronic venous insufficiency. Two studies were from Australia [20, 21], one from England [22], one from Ireland [23] and one from Sweden [24].

Description of studies

An overview of included studies is presented in Table 2. Four studies [20,21,22,23] with 653 participants examined the effects of compression stockings treatment on ulcer recurrence for patients with recently healed venous leg ulcers. Four studies [20, 21, 23, 24] used European standard for defining compression classes, and they compared different grades of compression. One study [22] used British standard and we redefined this to European standard. Two of the included studies [22, 23] reported education related to skin care and the use of compression stockings as part of the intervention, and two studies [21, 23] included self-reported assessment of compliance as part of the provided intervention.

One study included patients with signs of chronic venous insufficiency [20], whereas another study included patients with lipodermatosclerosis [21]. In two studies [20, 22] about 70% of the participants were women. Comorbidity and details about the application of the compression stockings were poorly reported in the included studies. However, in one study [21] the participants had to apply the compression stockings themselves. The fifth study [24] included 31 participants with chronic venous insufficiency grade II, comparing compression stockings class 2 and compression stockings class 1.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias assessments are summarized in Fig. 2. Four studies had low risk of selection bias. Three studies had high risk of performance and detection bias, whereas three studies had low risk of attrition bias, four studies had low risk of reporting bias and two studies had other biases (Fig. 2).

Effects on leg ulcer recurrence

Four trials [20,21,22,23] examined the effects of compression stockings treatment on ulcer recurrence for patients with healed venous leg ulcers. We were able to conduct a meta-analysis (Fig. 3) of two trials comparing two different strengths of compression stockings on the risk of ulcer recurrence [22, 23]. Ulcer recurrence was defined as epithelial breakdown anywhere below the knee lasting more than four weeks and requiring bandage treatment in one study [23], and as a skin break failed to heal in six weeks in the other study [22]. The meta-analysis included data from 399 participants and showed that compression stockings class 2 significantly reduced leg ulcer recurrence compared to compression stockings class 1 (RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.88) at 12 months. Hence, if 175 per 1000 patients receiving class 1 compression stockings experience ulcer recurrence, the corresponding number among patients who receive class 2 stockings will be 91 per 1000. We have moderate confidence in the effect estimate (Table 3).

Kapp et al. [20] compared the effects of compression stockings class 3 versus class 2. Healing date and anatomical location were used to determine time to ulcer recurrence and number of wounds, but the authors were not able to detect a difference in ulcer recurrence between the groups after six months (RR 0.64; 95% CI 0.20 to 2.03; 100 participants). Vandongen et al. [21] compared compression stockings class 3 to no compression stockings, and found that patients who wore stockings were at lower risk of ulcer recurrence after six months (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.76; 153 participants) and 12 months (RR 0.43; 95% CI 0.27 to 0.69). We have very low confidence in these effect estimates (Table 3).

Effects on vein thrombosis and mobility

None of the included studies reported risk of vein thrombosis or mobility.

Effects on secondary outcomes

Jungbeck et al. [24] compared compression stockings class 2 and class 1 in 31 patients with chronic venous insufficiency grade II. The effects were assessed measuring foot volume and subjective symptoms (e.g. pain, ankle swelling, tired legs, restless legs and night cramps) after eight weeks. Subjective symptoms were assessed by visual analogue scale (VAS). The authors were not able to detect a difference between class 2 and class 1 stockings on subjective symptoms after eight weeks, nor did they find a difference in foot volume or reflux values between the two groups. As the latter results were based on a single study with few participants and high risk of bias, we have very low confidence in these effect estimates.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we aimed to summarize the preventive effects of medical compression stockings for patients with chronic venous insufficiency and swollen legs. We included five randomized controlled trial. The main finding is that compression stockings class 2 probably reduce the risk of leg ulcer recurrence compared to compression stockings class 1. One included study [20] suggests that stockings of higher compression (class 3) were better than medium compression (class 2), but the study only included 100 participants and overall evidence was assessed as having low quality. Therefore, it remains uncertain whether the use of stockings with higher compression grades is associated with a further risk reduction. Moreover, it is uncertain whether the use of compression stockings reduces subjective symptoms and foot volume for patients with chronic venous insufficiency. We found no studies investigating the preventive use of compression stockings for patients with venous insufficiency or swollen legs on vein thrombosis or mobility.

The results we present on risk of ulcer recurrence are in accordance with the review of Nelson et al. [15]. The evidence is sparse, but class 2 compression stockings seem to be more effective than lower class stockings in the prevention of ulcer recurrence. Consistent with our findings, another review [16] states that the evidence is too sparse to allow firm conclusions about the effects of compression stockings for the initial treatment of varicose veins in patients without ulceration.

Two additional primary studies [9, 10] have shown that compression stockings are effective in reducing pain and symptoms in patients younger than 70 years suffering from chronic venous insufficiency. Moreover, a randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of progressive compression stockings (compression with maximal pressure at calf) [25] reported that progressive compression stockings (10 mmHg at ankle, 23 mmHg at upper calf) were more effective than ordinary compressive stockings (30 mmHg at ankle, 21 mmHg at upper calf) in reducing pain and heavy legs. However, the patients in the latter studies were too young to be included in our review, and the applicability to a geriatric population can be questioned.

The available evidence suggests that compression stockings may play a role in the prevention of ulcer recurrence, but the evidence has limitations. In addition to lack of blinding, attrition bias associated with incomplete outcome assessment and poor patient compliance reduces the quality of evidence. Patient compliance with the recommended regimen varies between studies and between treatment groups and it seems like the compliance rates decrease for stockings with higher compression grades. Three of the included studies did not report reasons for noncompliance [20,21,22], whereas one study reported that noncompliance was explained by tightness, inability to apply or remove the compression stockings and skin sensitivity [23]. The same study reported that poor compliance was associated with lower effect [23], but these findings were contradicted by studies reporting that the overall results did not change significantly when non-compliant patients were excluded from the analysis [20, 22].

It is reasonable to expect that poor compliance not only impact the effect of compression stockings, but also poses a challenge in ordinary practice. Healthcare professionals should focus on methods that improve patient compliance. Compression stockings may be a resource-demanding intervention, as elderly people with chronic venous insufficiency often need assistance from home care personnel to administer the stockings. Health professionals in close dialogue with each individual patient should evaluate the need for compression stockings before and during the treatment, because of the personnel cost, and the sparse and inconsistent body of the evidence.

A major strength of this systematic review is the extensiveness of the systematic search. Even though the search was comprehensive, only five randomized trials were included and no relevant ongoing studies were found. It is a limitation that the quality of the evidence was graded from moderate to very low, implying there is a need for further research on these topics before we can make a firm conclusion about the effects of preventive use of compression stockings.

Based on this systematic review, the prevalence of venous disease and the resources associated with the treatment [3], the research activity should continue to target this very important issue, preferably with more well-designed RCTs. In particular, there is a need for further studies about the preventive use of compression stockings for elderly patients with venous insufficiency and swollen legs. It is important to measure outcomes such as vein thrombosis and mobility in addition to leg ulcers.

Conclusions

Based on the results of this systematic review, medical compression stockings probably reduce leg ulcer recurrence up to one year in elderly people, but the effect after one year is unclear. However, the evidence of initial treatment with compression stockings in patients with venous insufficiency or swollen legs is lacking.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- SR:

-

Systematic review

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Moneta G. Classification of lower extremity chronic venous disorders Waltham: UpToDate; 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/8177. Accessed 19 Apr 2018.

Alguire PC, Mathes BM. Post-thrombotic (postphlebitic) syndrome Waltham: UpToDate; 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/8200. Accessed 27 Feb 2018.

Slagsvold CE, Stranden E, Rosales A. Venous insufficiency in the lower limbs. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2009;129:2256–9.

Maurins U, Hoffmann BH, Losch C, Jockel KH, Rabe E, Pannier F. Distribution and prevalence of reflux in the superficial and deep venous system in the general population--results from the Bonn vein study, Germany. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:680–7.

Ruckley CV, Evans CJ, Allan PL, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG. Chronic venous insufficiency: clinical and duplex correlations. The Edinburgh vein study of venous disorders in the general population. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:520–5.

Mills JL, Armstrong DG. Chronic venous insufficiency. London: BMJ; 2017. http://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/507. Accessed 27 Feb 2018.

Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, Frulla M, Marchiori A, Bernardi E, et al. Below-knee elastic compression stockings to prevent the post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:249–56.

Armstrong DG, Meyr AJ. Compression therapy for the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. Waltham, MD: UpToDate; 2017. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/15199. Accessed 27 Feb 2018.

Carvalho CA, Lopes Pinto R, Guerreiro Godoy Mde F, Pereira de Godoy JM. Reduction of Pain and Edema of the Legs by Walking Wearing Elastic Stockings. Int J Vasc Med. 2015;2015:648074.

Al Shammeri O, AlHamdan N, Al-Hothaly B, Midhet F, Hussain M, Al-Mohaimeed A. Chronic venous insufficiency: prevalence and effect of compression stockings. Int J Health Sci. 2014;8:231–6.

Berntsen CF, Kristiansen A, Akl EA, Sandset PM, Jacobsen EM, Guyatt G, et al. Compression Stockings for Preventing the Postthrombotic Syndrome in Patients with Deep Vein Thrombosis. Am J Med. 2016;129:447 e1–e20.

Burgstaller JM, Steurer J, Held U, Amann-Vesti B. Efficacy of compression stockings in preventing post-thrombotic syndrome in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Vasa. 2016;45:141–7.

Cohen JM, Akl EA, Kahn SR. Pharmacologic and compression therapies for postthrombotic syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2012;141:308–20.

Jin YW, Ye H, Li FY, Xiong XZ, Cheng NS. Compression stockings for prevention of Postthrombotic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;50:328–34.

Nelson EA, Bell-Syer SE. Compression for preventing recurrence of venous ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;(Issue 9):CD002303. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002303.pub3.

Shingler S, Robertson L, Boghossian S, Stewart M. Compression stockings for the initial treatment of varicose veins in patients without venous ulceration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(Issue 12):CD008819. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008819.pub3.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 27 Feb 2018.

Review Manager (RevMan) [software]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT) [software]. McMaster University and Evidence Prime Inc.; 2015. https://gradepro.org/. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Kapp S, Miller C, Donohue L. The clinical effectiveness of two compression stocking treatments on venous leg ulcer recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Lower Extrem Wounds. 2013;12:189–98.

Vandongen Y, Stacey M. Graduated compression elastic stockings reduce lipodermatosclerosis and ulcer recurrence. Phlebology. 2000;15:33–7.

Nelson E, Harper D, Prescott R, Gibson B, Brown D, Ruckley C. Prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration: randomized controlled trial of class 2 and class 3 elastic compression. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:803–8.

Clarke-Moloney M, Keane N, O'Connor V, Ryan M, Meagher H, Grace P, et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing European standard class 1 to class 2 compression stockings for ulcer recurrence and patient compliance. Int Wound J. 2014;11:404–8.

Jungbeck C, Thulin I, Darenheim C, Norgren L. Graduated compression treatment in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: a study comparing low and medium grade compression stockings. Phlebology. 1997;12:142–5.

Couzan S, Leizorovicz A, Laporte S, Mismetti P, Pouget J, Chapelle C, et al. A randomized double-blind trial of upward progressive versus degressive compressive stockings in patients with moderate to severe chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1344–50.e1.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Frantz Leonard Nilsen, Kari Kongshavn and Randi Aasen for relevant information on selection criteria and discussion. We acknowledge the assistance of Ellinor Bakke Aasen in commenting on the protocol.

Funding

Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Norway supported this review.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KTD and HTM took an active role in the literature data collection, evaluation and synthesis. They worked closely with HS in developing the search strategy. HS also helped to screen abstracts and full-text articles and commenting on the manuscript. KGB contributed to interpret and analyse results and editing the manuscript. BF used his expertise specially in commenting on the introduction and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategies. (PDF 263 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahm, K.T., Myrhaug, H.T., Strømme, H. et al. Effects of preventive use of compression stockings for elderly with chronic venous insufficiency and swollen legs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 19, 76 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1087-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1087-1