Abstract

Background

Hand-grip strength (HGS) serves as a proxy measure for muscle function and physical health. Studies have shown that low HGS is associated with common age-related disorders including frailty and sarcopenia. The aim of the present study was to establish the normative values of HGS among older adults in Singapore and to compare it with data from Western and other Asian countries. The study also aimed to explore the sociodemographic and anthropometric correlates of HGS.

Methods

Data were collected from 2043 men and women aged 60 years and above who took part in the Well-being of the Singapore Elderly study in 2013. HGS was obtained using a Jamar Plus + digital hand dynamometer. Normative data were stratified by; 5-year age groups, sex and ethnicity. Relationships between the HGS with various sociodemographic and anthropometric correlates were examined using multiple linear regression analysis.

Results

The mean HGS demonstrate a decreasing trend with increased age across all ethnic groups and sexes. HGS among Singapore older adults were relatively low compared to Western and other Asian countries. Males in the youngest age group (60-64) and of Chinese ethnicity attained greater HGS values than their counterparts. When the regression analysis was stratified for sex, significant associations were found between height, upper arm circumference with HGS in the males sample, and between height, weight, waist circumference and HGS in the females sample.

Conclusions

Older adults in Singapore have a relatively weak HGS compared to other countries. Greater height and weight, and smaller waist circumference are independently associated with greater HGS in females but not males. These results facilitate the interpretation of HGS conducting using Jamar digital-type dynamometers among the older adults in Singapore.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hand-grip strength (HGS) plays an important role in the daily lives of people and serves as a reliable proxy indicator of an individual’s hand motor abilities. Many daily functions such as carrying require the use of the flexor musculature of the forearms and hands, and these are the muscles that are involved in gripping strength. Recent studies have reported the importance of HGS as it is used to help identify common age-related disorders such as frailty and sarcopenia [1, 2]. HGS can be measured using different assessors such as the Nintendo Wii Balance Board and Grip-ball [3, 4] or using different brands of dynamometer i.e. Rolyan, Smedley, and Jamar dynamometers [5, 6]. Hand-grip dynamometer was found to be a valid tool in clinical and research practice, and is an easy, quick, and inexpensive way of assessing HGS in older adults [3].

Several publications have appeared in recent years documenting HGS normative values in older adults in United States (US) [7], United Kingdom (UK) [8], Japan [9], Hong Kong [10], Taiwan [11, 12], Malaysia [13] and Singapore [6]. Dodds et al. [14] studied differences in HGS by world region and reported that the HGS normative data between the British and developed regions (e.g. US and UK) were more similar and found lower normative data in developing regions (e.g. China and Taiwan). Most of these studies stratified data into age and sex subgroups and found higher HGS in males as compared to females at all ages and a gradual decline with increasing age. Likewise, HGS continues to decline after stratifying the data by sex, dominant and non-dominant hand, and right and left hand, as age increases [15].

The focus of recent research has been on the correlates of HGS which were documented in various studies. Auyeung et al. [2] studied the sex differences in the annualized HGS decline rate and found that females had a faster rate of grip strength decline compared to males, whereas other studies found faster decline rate in males than females [7, 10]. Other sociodemographic correlates such as ethnicity and occupation [6, 13]; and anthropometric correlates such as height [16, 17], upper arm circumference [18], and waist circumference [19] were also found to be associated with HGS. Other than correlates, recent studies also shown significant positive associations of HGS with physical and mental health, such as dementia among older adults in Singapore [20], cardiovascular mortality, and stroke [21].

Singapore is a Southeast Asian country with a population of 5.54 million of which 3.90 million comprise the resident population. The multi-ethnic population has a majority of those belonging to the Chinese ethnicity (74.3%), followed by Malays (13.3%), Indians (9.1%), and others (3.2%) [22]. The average life expectancy has increased over the years. For males it is currently 80.6 years (2004: 77.1 years) while for females it is 85.1 years (2004: 82.0 years). As of 2015, there were a total of 700,208 older adults aged 60 years or above, accounting for 17.9% of the total Singapore population [22].

Malhotra et al. [6] recently published normative values for HGS using data obtained from the national Social Isolation, Health, and Lifestyles Survey (SIHLS), conducted in 2009. However, this study only assessed the sociodemographic correlates of HGS such as age, sex, ethnicity, education level and occupation, but did not account for anthropometric correlates of HGS such as, upper arm and waist circumference. Both correlate with HGS [18, 19]. Furthermore no comparisons were made between data from Singapore with that of Western and other Asian countries to understand the HGS performance of older adults in Singapore.

The current study aimed to: (1) establish the normative HGS values in the Singaporean older adults stratified by age, sex, and ethnicity; (2) compare Singapore older adults’ HGS data to Western and other Asian countries; (3) examine sociodemographic correlates of HGS, and; (4) explore the relationship of HGS with other anthropometric measurements (i.e. height, weight, upper arm circumference, and waist circumference) controlling for sociodemographic correlates.

Methods

Study participants

Study approval was obtained from the relevant ethics committees in Singapore -National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board and the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board. Older adults aged 60 years and above were randomly selected from a national database which consisted of administrative data (i.e. name, ethnicity, gender, and residential address) of all citizens and permanent residents in Singapore. These selected participants were notified of the study by mail and then approached at home by interviewing staff. Older adults who resided in day care centres, nursing homes, and institutions were also included. Individuals who were not living in Singapore and who could not be contacted due to invalid addresses were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. In the case where participants were unable to provide consent, consent was taken from their legally acceptable representative or next-of-kin. For each older adult, an informant of each participant- “someone who knew the participant best”, was also invited to take part in the survey. The informant could be either caregivers, co-residents or someone who had close contact with the older person but was not involved in a caregiver role. Informants provided information on participants only when the participant could not provide the relevant information, such as questions on “participant background information” and “physical health condition” [23]. Disproportionate stratified sampling design was used where residents in the older age group and those from Malay and Indian ethnic group were over-sampled to ensure that sufficient sample size would be achieved to improve the reliability of estimates for the subgroups analysis. A detailed description of the methodology can be found in an earlier paper [23].

Materials and assessments

All measurements and data on sociodemographic information were collected by trained interviewers. Hand dominance was determined by asking which hand they use for writing or which hand they would predominantly use when performing a task. HGS was measured in kilograms (kg) by taking the average of the two dominant handgrip attempts using a Jamar Plus + Digital Hand Dynamometer (Pennsylvania, United States). The device measures the isometric muscle contractions as the participant grip against the resistance of the stationary grip handle. For each of the HGS assessments, subjects were instructed by trained interviewers to sit as per the American Society of Hand Therapist’s (ASHT) recommendation for HGS; with their shoulder adducted and neutrally rotated, elbow flexed at 90o with the forearm in neutral position for HGS measurement [24].

Sociodemographic information on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status were collected from participants and verified with informants. Anthropometric measurements were carried out with a brief fully structured physical and neurological assessment, the NEUROEX [25], which included height, weight, HGS, upper arm circumference, and waist circumference. Upper arm circumference was measured in centimetres using a measuring tape around the thickest part of the upper arm of the dominant hand [26]. Participants were instructed to have their shoulders relaxed and both arms hanging loosely at the sides as flexing or tightening the arm muscle would results in an inaccurate measurement. Waist circumference measured in centimetres was measured at the narrowest part of the body between the chest and hips for females, and measured at the level of the umbilicus for males [27].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) system version (9.3). To ensure that the survey findings were representative of the Singapore population, all estimates were analysed using survey weights to adjust for complex survey data. We have computed survey weights that incorporate sampling weight, non-response weight and post-stratification weight which was used to weigh the sample back to the population to adjust for oversampling, non-response and post-stratify by age and ethnicity distributions between the survey sample and the Singapore elderly population. This approach has been recommended when analysing complex survey data [28]. Those diagnosed with dementia using 10/66 diagnostic criteria [29] were excluded from the analysis since dementia is associated with poor HGS [20, 30].

Mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. HGS were calculated and presented separately by age, sex and ethnicity. We used 6 age groups categories to present the data: 60–64 years, 65–69 years, 70–74 years, 75–79 years, 80–84 years and 85+ years. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to explore the sociodemographic and anthropometric correlates of HGS. Standard errors (SE) of means, regression coefficients and other statistics were estimated using the Taylor series’ linearization method to adjust for the weighting. Multivariate significance was evaluated using Wald X2 tests based on design corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated at the 0.05 level using 2-sided tests.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The descriptive data are listed in Table 1. A total of 2565 older residents participated in the study, giving a response rate of 66%. Of the 2565 participants who completed the study, 2043 participants aged 60 years and over were included in our study sample. Those with missing HGS data (n = 171, mostly because of health reasons) and dementia (n = 399) were excluded. Further, the results for those who were left-handed were excluded due to small sample size (n = 84). The mean age was 68.8 years, ranging from 60 to 105 years. 82.9% were of Chinese descent, 9.3% were Malays descent, 6.2% were of Indian descent, and 1.7% belonged to other ethnic groups. Majority of the sample were women (54.3%), married/ cohabiting (66.8%), had completed primary education (25.1%), and were employed (37.5%).

Hand-grip strength by age, sex, and ethnicity

Table 2 shows the means and standard deviation of HGS by age group, sex and ethnicity. The mean HGS for the males and females participants in the youngest age group (60-64years) was 31.1 kg and 18.2 kg respectively while it dropped to 18.5 kg for males and 12.4 kg for females participants in the oldest age group (85+ years). The mean HGS showed a decreasing trend with increasing age among all three ethnic groups in both sexes.

Sociodemographic correlates of hand-grip strength

Table 3 shows the sociodemographic correlates of HGS. HGS was significantly greater in the youngest age group (60-64) than the other older age groups, 70-74 (β = −3.29, p < 0.001), 75-79 (β = −5.28, p < 0.001), 80-84 (β = −5.94, p < 0.001), and 85+ (β = −9.15, p < 0.001) and in males (β =10.76, p < 0.001) than females. Those of Malay (β = −2.01, p < 0.001) and Indian (β = −1.64, p < 0.001) ethnicity had significantly lower HGS values than Chinese after adjusting for other sociodemographic correlates.

Multivariate analysis to test the association of anthropometric measurements with hand-grip strength

Table 4 shows the association between HGS with height, weight, upper arm circumference, and waist circumference after adjusting for sociodemographic and other anthropometric correlates. Multiple linear regression were conducted and for the overall sample, HGS was found to be significantly associated with height (β = 0.12, p = 0.001), weight (β = 0.09, p = 0.019), and inversely associated with waist circumference (β = −0.08, p = 0.018).

Stratified regression analysis showed that for males, only height (β = 0.17, p = 0.010) and upper arm circumference (β = 0.33, p = 0.004) were significantly positively associated with HGS. For females, the findings were similar to the overall sample where HGS was significantly associated with height (β = 0.10, p = 0.016), weight (β = 0.13, p = 0.009), and waist circumference (β = −0.09, p = 0.020).

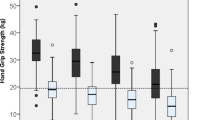

Comparison between Singapore and other countries

The summary details of the eight included studies for HGS comparison are listed in Table 5. HGS data was compared with Western (i.e. US, UK) and other Asian countries (i.e. Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore). For both sexes, HGS among Singapore older adults were relatively low compared to Western and other Asian countries except for Taiwan (Figs. 1 and 2). US and UK had the highest mean HGS followed by Japan, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. Only right-handed HGS data were extracted from other studies for comparison.

Discussion

In this article we examined the HGS values among the Singaporean older adults, as well as the sociodemographic correlates and its association with anthropometric correlates. Our results showed significant association between HGS and sociodemographic correlates; age, sex, and ethnicity. Significant associations were also found between HGS and anthropometric measurement; height, weight, upper arm circumference and waist circumference. Particular attention was paid to the sex differences in the association of HGS with anthropometric measurements. In females, increasing height, weight and decreasing waist circumference were associated with HGS, while in males, only increasing height and upper arm circumference were associated with HGS.

Our findings are in good agreement with other studies which found an association between HGS with other sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, and ethnicity [13, 31, 32]. Possible underlying mechanisms have been proposed for the association between HGS with age, sex, and ethnicity. As individuals' age, their bodies would experience age-related degenerative changes in the musculoskeletal, vascular, and nervous systems. These degenerative changes would cause deterioration of hand function in older adults and affect the hand structure such as joints, muscle, tendon, bone, nerve and receptors, blood supply, skin, and fingernails [33]. Furthermore, studies have reported major reduction of muscle mass and ability to activate the biceps brachii muscle as one ages [34]. For sex differences, Miller et al. [35] compared body mass, muscles fibres number, fibres size and fibres area between young males and females. Compared to females, males were stronger relative to lean body mass and had significantly larger type 1 fibre areas and mean fibre areas in biceps brachii. Males were reported to have a larger number of muscle fibres which contribute to the greater strength than females [35].

Few studies have looked into the ethnic differences in grip strength among populations in Southeast Asia [13, 36]. In a study conducted in rural Pahang, Malaysia, ethnic differences in grip strength was reported where the aborigines had significantly lower grip strength compared to the Malaysian Malays, Chinese, and Indians [36]. Genetic variation [37], health status and different lifestyle could account for the observed differences between Chinese, Malays, and Indians [38].

Consistent with other studies, significant associations were found between HGS with height, weight, and waist circumference in older adults [19, 39, 40]. For height, Samaras et al. [41] indicated that taller people have greater absolute strength. Absolute strength is related to muscle cross-sectional area and is correlated with the body surface area or the square of body height. Other than the cross-sectional area, factors such as nutrition in early life are reported to have positive influence on individuals’ grip strength [42]. Larger waist circumference, which is a clinical indicator of central obesity, is associated with lower grip strength [19]. Abdominal fat secretes cytokines and hormones (adipokines) and a relationship between higher cytokines levels and lower muscle mass and lower muscle strength has been reported [43]. Negative relationship between adipokines and strength and aerobic fitness in older adults has also been reported [44].

Our paper presents an interesting view of gender differences in the association of HGS with other anthropometric measurements. Compared to the overall and females’ data, for males there was a significant association between HGS and upper arm circumference but not with weight and waist circumference. Possible reasons could be due to the employment-type differences between men and women. According to the Labour Force Survey in Singapore 2015 [45], the resident employment participation rate for older men aged 65 and over was higher than older women aged 65 and over (36.0% vs. 17.6%). Among employed residents aged 60 and over, more men engaged in occupations i.e. “Production & Transport Operators, Cleaners & Labourers” (78.0% vs. 43.3%) than women, while more women engaged in “Clerical, Sales & Service Workers” (37.6% vs. 31.5%) than men. In the present study, there were more males than females in skilled labourer, 21% vs. 5%. Given that labour-intensive jobs require workers to have good physical condition and strength, it is plausible that men who engaged in these jobs have greater upper arm strength and therefore a significant association of upper arm circumference with HGS. Further research on the role of gender on the relationship between different anthropometric correlates (i.e. upper arm circumference and waist circumference) with HGS is necessary to extend our knowledge of HGS further.

Comparison with other countries

Overall, Singapore older adults’ mean HGS was lower compared to other countries. The HGS for both genders were generally lower compared to older adults in UK [8], US [7], Japan [9], Hong Kong [10] and Malaysia [13] but was comparable to a previous study conducted in Singapore [6] and Taiwan [13]. Several possible reasons could explain the difference in normative HGS data between countries and these include differences in body composition such as mean height, weight, body sizes, palm size and ways of measuring grip strength e.g. sitting or standing positions and the brand of dynamometer [11].

The norms of HGS may differ between populations within Europe and East Asia. The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) study conducted in 11 European countries found lower HGS in the southern countries (Spain, Italy, and Greece) compared to northern and continental countries (Sweden, Denmark, Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and France) [46]. In a study by Lin et al. [47] which assessed the anthropometric characteristics of adults from East Asian countries (i.e. China, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea), significant morphological difference were reported among these peoples in the same region [47]. Clearly these differences in anthropometric measurements within regions are likely to be explained by a range of factors such as nutrition and genetic factors which may also account for the differences seen in HGS among countries [48].

Varying methods of measuring grip strength could also explain the difference in grip strength across and within countries. The previous study mentioned- SHARE study - which included data from 11 European countries, used the hand-grip dynamometer, Smedley, while another systematic review using data from 12 British general population studies different dynamometers (Smedley and Jamar) in the seated and standing position (refer to Table 5) were used for the data collection. A systematic review by Roberts et al. [49] found a wide variability in the choice of grip strength measuring equipments and protocols across clinical and epidemiological studies. Furthermore, evidence pointed that variation in approach can affect the values recorded and summary measures of grip strength varied widely including maximum or mean value, from one, two or three attempts, with either hand or the dominant hand alone [49].

Within Singapore, the present study reported similar normative HGS data as Malhotra et al. [6], yet the minimal differences in data reported could be attributed to possible reasons such as individual differences, cohort effect (national survey conducted in 2009 vs. present study: 2013), and instrument used to measure HGS (Smedley spring-type dynamometer vs. present study: Jamar digital-type dynamometer), and position (standing position vs. present study: sitting position). All these findings highlight the importance of having a standardized method of assessing HGS to facilitate comparison between studies and enable consistent measurement of grip strength [49, 50].

Limitations and strengths

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the light of the following limitations. Firstly, the generalizability of the study is limited. The present paper only includes participants with HGS measurements, not diagnosed with 10/66 dementia, and right-handed individuals. Future studies could explore the anthropometric correlates of HGS for both right and left hands. Secondly, there is also the possibility that the participants, who are older, may not have understood the instructions during HGS measurement and that could affect the validity of the measurements taken [20, 51]. To reduce the likelihood of such occurrence, all interviewers received standardized instructions and training from senior researchers to ensure proper use of the equipment and demonstrations of using the Jamar dynamometer were conducted for all subjects. All participants were also briefed in the language chosen by participants according to their familiarity and comfort.

Despite these limitations stated above, results from this study hold important implications on the healthcare of the older adults in Singapore. In terms of external comparisons, Singapore older adults’ have generally lower HGS compared to other countries. The comparison allows clinicians to gauge the performance of Singapore older adults’ HGS performance and offer a better standard for treatment and interventions, and researchers could use the normative data as baseline to study the trend for comparison with future studies. For internal comparisons, the normative grip strength data allow individuals to interpret what is typical in their country. It served as a reference point for comparison to someone of the same age, gender, and ethnicity to determine if their personal HGS is higher or lower than what is typical in their country. However, care must be taken for comparison. Since height, weight, upper arm circumference, and waist circumference were found to be associated with HGS, thus the result would be more useful as a gauge than a strict benchmark [11].

Our study was the first in Singapore that examines the anthropometric correlates of HGS in Singapore older adults and makes comparison with the available HGS data of Western and other Asian countries. Our results suggest that ethnicity and gender differences exist for the anthropometric correlates of HGS (males: height and upper arm circumference; females: height, weight, and waist circumference) in Singapore, which might also explain some of the differences between Singapore older adults against other countries.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that sociodemographic correlates (i.e. age, sex, and ethnicity) and anthropometric correlates (i.e. height, weight, upper arm circumference and waist circumference) were associated with HGS in Singapore older adults. Moreover, the study found that Singaporean older adults had weaker grip strength than that of older adults from Western and other Asian countries.

Abbreviations

- ASHT:

-

American Society of Hand Therapist

- HGS:

-

Hand-grip strength

- SHARE:

-

Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe

- SIHLS:

-

Social Isolation, Health, and Lifestyles Survey

- WiSE:

-

Well-being of Singapore elderly

References

Sayer AA, Syddall H, Martin H, Patel H, Baylis D, Cooper C. The developmental origins of sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:427–32.

Auyeung TW, Lee SW, Leung J, Kwok T, Woo J. Age-associated decline of muscle mass, grip strength and gait speed: A 4-year longitudinal study of 3018 community-dwelling older chinese. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(Suppl 1):76–84.

Vermeulen J, Neyens JC, Spreeuwenberg MD, van Rossum E, Hewson DJ, de Witte LP. Measuring grip strength in older adults: Comparing the grip-ball with the jamar dynamometer. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2015;38:148–53.

Blomkvist AW, Andersen S, de Bruin ED, Jorgensen MG. Isometric hand grip strength measured by the nintendo wii balance board - a reliable new method. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:56.

Mathiowetz V. Comparison of rolyan and jamar dynamometers for measuring grip strength. Occup Ther Int. 2002;9:201–9.

Malhotra R, Ang S, Allen JC, Tan NC, Ostbye T, Saito Y, et al. Normative values of hand grip strength for elderly singaporeans aged 60 to 89 years: A cross-sectional study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:864. e1-7

Jansen CWS, Niebuhr BR, Coussirat DJ, Hawthorne D, Moreno L, Phillip M. Hand force of men and women over 65 years of age as measured by maximum pinch and grip force. J Aging Phys Act. 2008;16:24.

Dodds RM, Syddall HE, Cooper R, Benzeval M, Deary IJ, Dennison EM, et al. Grip strength across the life course: Normative data from twelve british studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113637.

Seino S, Shinkai S, Fujiwara Y, Obuchi S, Yoshida H, Hirano H, et al. Reference values and age and sex differences in physical performance measures for community-dwelling older japanese: A pooled analysis of six cohort studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99487.

Chung PK, Zhao Y, Liu JD, Quach B. Functional fitness norms for community-dwelling older adults in hong kong. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;65:54–62.

Wu SW, Wu SF, Liang HW, Wu ZT, Huang S. Measuring factors affecting grip strength in a taiwan chinese population and a comparison with consolidated norms. Appl Ergon. 2009;40:811–5.

Wang CY. Hand dominance and grip strength of older asian adults. Percept Mot Skills. 2010;110:897–900.

Lam NW, Goh HT, Kamaruzzaman SB, Chin AV, Poi PJ, Tan MP. Normative data for hand grip strength and key pinch strength, stratified by age and gender for a multiethnic asian population. Singap Med J. 2016;57:578–84.

Dodds RM, Syddall HE, Cooper R, Kuh D, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Global variation in grip strength: A systematic review and meta-analysis of normative data. Age Ageing. 2016;45:209–16.

Bohannon RW, Peolsson A, Massy-Westropp N, Desrosiers J, Bear-Lehman J. Reference values for adult grip strength measured with a jamar dynamometer: A descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2006;92:11–5.

Hossain MG, Zyroul R, Pereira BP, Kamarul T. Multiple regression analysis of factors influencing dominant hand grip strength in an adult malaysian population. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2012;37:65–70.

Hardy R, Cooper R, Aihie Sayer A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Cooper C, Deary IJ, et al. Body mass index, muscle strength and physical performance in older adults from eight cohort studies: The halcyon programme. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56483.

Yun YD, Jeong YA, Min JH, Yoo KT, Choi JH. Analysis on the change of hand grip strength as per the circumference of upper arm and forearm and the muscle activity of upper arm and forearm as per the duration of gripping. J Int Acad Physical Ther Res. 2013;4:532.

Keevil VL, Luben R, Dalzell N, Hayat S, Sayer AA, Wareham NJ, et al. Cross-sectional associations between different measures of obesity and muscle strength in men and women in a british cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:3–11.

Ong HL, Chang SH, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Jeyagurunathan A, Shafie S, et al. Association of grip strength, upper arm circumference, and waist circumference with dementia in older adults of the wise study: A cross-sectional analysis. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20:996–1001.

Leong DP, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Avezum A Jr, Orlandini A, et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: Findings from the prospective urban rural epidemiology (pure) study. Lancet. 2015;386:266–73.

Department of Statistics Singapore. Population trends. 2015. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/statistics/visualising_data/population-trends2015.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2015.

Subramaniam M, Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Chua BY, Chua HC, et al. Prevalence of dementia in people aged 60 years and above: Results from the wise study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:1127–38.

Fees E, Moran C. American society of hand therapists clinical assessment recommendations. 1981.

10/66 Dementia Research Group. Population–based epidemiological studies (prevalence phase): Methods. 2015. http://www.alz.co.uk/1066/pop_based_ep_studies_prevalence_phase_methods.php. Accessed 31 May 2015.

Lee YS, Kim SD, Kang HJ, Kim SW, Shin IS, Yoon JS, et al. Associations of upper arm and thigh circumferences with dementia and depression in korean elders. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14:150–7.

Taylor CL, Albanese E, Stewart R. The association of dementia with upper arm and waist circumference in seven low- and middle-income countries: The 10/66 cross-sectional surveys. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:897–904.

Heeringa S, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2010.

Prince M, Acosta D, Chiu H, Scazufca M, Varghese M, Dementia RG. Dementia diagnosis in developing countries: A cross-cultural validation study. Lancet. 2003;361:909–17.

Bullain SS, Corrada MM, Shah BA, Mozaffar FH, Panzenboeck M, Kawas CH. Poor physical performance and dementia in the oldest old: The 90+ study. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:107–13.

Yorke AM, Curtis AB, Shoemaker M, Vangsnes E. Grip strength values stratified by age, gender, and chronic disease status in adults aged 50 years and older. In J Geriatr Phys Ther. 38:115–21. United States: Issues on Aging; 2015:115-21

Koh J, Ho S. Culture and customs of singapore and malaysia. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO; 2009.

Carmeli E, Patish H, Coleman R. The aging hand. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:146–52.

Yue GH, Ranganathan VK, Siemionow V, Liu JZ, Sahgal V. Older adults exhibit a reduced ability to fully activate their biceps brachii muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M249–M53.

Miller AE, MacDougall JD, Tarnopolsky MA, Sale DG. Gender differences in strength and muscle fiber characteristics. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1993;66:254–62.

Moy F, Chang E, Kee K. Predictors of handgrip strength among the free living elderly in rural pahang, malaysia. Iran J Public Health. 2011;40:44–53.

McEvoy BP, Visscher PM. Genetics of human height. Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7:294–306.

Watson J, Ring D. Influence of psychological factors on grip strength. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2008;33:1791–5.

Shim JH, Roh SY, Kim JS, Lee DC, Ki SH, Yang JW, et al. Normative measurements of grip and pinch strengths of 21st century korean population. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:52–6.

Ramlagan S, Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N. Hand grip strength and associated factors in non-institutionalised men and women 50 years and older in south africa. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:8.

Samaras TT, Bartke A, Rollo CD. Human body size and the laws of scaling: Physiological, performance, growth, longevity and ecological ramifications. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2007.

Bielemann RM, Gigante DP, Horta BL. Birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction and nutritional status in childhood in relation to grip strength in adults: From the 1982 pelotas (brazil) birth cohort. Nutrition. 2016;32:228–35.

Visser M, Pahor M, Taaffe DR, Goodpaster BH, Simonsick EM, Newman AB, et al. Relationship of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with muscle mass and muscle strength in elderly men and women: The health abc study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M326–32.

Aguirre LE, Jan IZ, Fowler K, Waters DL, Villareal DT, Armamento-Villareal R. Testosterone and adipokines are determinants of physical performance, strength, and aerobic fitness in frail, obese, older adults. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:507395.

Ministry of Manpower. Labour force in singapore 2015. 2015. http://stats.mom.gov.sg/Pages/Labour-Force-In-Singapore-2015.aspx. Accessed 13 Aug 2015.

Andersen-Ranberg K, Petersen I, Frederiksen H, Mackenbach JP, Christensen K. Cross-national differences in grip strength among 50+ year-old europeans: Results from the share study. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6:227–36.

Lin YC, Wang MJ, Wang EM. The comparisons of anthropometric characteristics among four peoples in east asia. Appl Ergon. 2004;35:173–8.

Jeune B, Skytthe A, Cournil A, Greco V, Gampe J, Berardelli M, et al. Handgrip strength among nonagenarians and centenarians in three european regions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:707–12.

Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, Patel HP, Syddall H, Cooper C, et al. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: Towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing. 2011;40:423–9.

Liao WC, Wang CH, Yu SY, Chen LY, Wang CY. Grip strength measurement in older adults in taiwan: A comparison of three testing positions. Australas J Ageing. 2014;33:278–82.

Shin HY, Kim SW, Kim JM, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Association of grip strength with dementia in a korean older population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:500–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The WiSE study was funded by the Ministry of Health, Singapore, and the Singapore Millennium Foundation of the Temasek Trust. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data is not available for online access, however readers who wish to gain access to the data can write to the senior author Dr. Mythily Subramaniam at mythily@imh.com.sg with their requests. Access can be granted subject to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the research collaborative agreement guidelines. This is a requirement mandated for this research study by our IRB and funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HLO & EA are joint first authors. EA provided the analysis and interpretation of data. BYC, YZ, ES, JAV, SAC, MS provided the concept and design of study and provided intellectual input into article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Domain Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group, Singapore and SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board, Singapore. All participants provided written informed consent and in the case of respondents who were unable to provide informed consent, written informed consent was taken from their legally acceptable representative/next of kin.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ong, H.L., Abdin, E., Chua, B.Y. et al. Hand-grip strength among older adults in Singapore: a comparison with international norms and associative factors. BMC Geriatr 17, 176 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0565-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0565-6