Abstract

Background

A single-centre cohort study was performed to identify the independent factors associated with the overall survival (OS) of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads (DEB-TACE).

Methods

A total of 216 HCC patients who underwent DEB-TACE from October 2008 to October 2015 at a tertiary hospital were consecutively recruited. The analysis of prognostic factors associated with overall survival after DEB-TACE, stressing the role of post-TACE events, was performed.

Results

The objective response (OR) rate (Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) criteria) to the first DEB-TACE (DEB-TACE-1) was 70.3%; the median OS from DEB-TACE-1 was 27 months (95% confidence interval (CI), 24–30). In the multivariate analysis, tumor size, AFP < 100 ng/mL and serum alkaline phosphatase were independent factors for survival following DEB-TACE-1. The most important clinical event associated with poor survival was the development of early ascites after DEB-TACE-1 (median OS, 17 months), which was closely related to the history of ascites, albumin and hemoglobin but not to tumour load or to response to therapy.

Conclusions

Early ascites post-DEB-TACE is associated with the survival of patients despite adequate liver function and the use of a supra-selective technical approach. History of ascites, albumin and hemoglobin are major determinants of the development of early ascites post-DEB-TACE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and is the fourth-leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1, 2]. According to the European and American guidelines [3, 4], transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the first-line treatment for asymptomatic patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) B stage disease (which includes multinodular HCC beyond the Milan criteria, without portal invasion or extrahepatic disease) and compensated liver function. TACE is performed not only in BCLC-B patients but also in early-stage patients if resection, ablation or liver transplantation is not feasible. Thus, TACE candidates represent a heterogeneous group of patients with variable tumour burden and liver function [5].

TACE is an image-guided transcatheter tumour therapy that has an ischaemic and cytotoxic effect on tumour tissue. The use of drug-eluting embolic chemoembolization (DEB-TACE) is safe and effective [6, 7]. However, an improvement in the overall survival (OS) of DEB-TACE compared to that of conventional TACE has not been confirmed [8, 9].

Considering the heterogeneity of TACE candidates, patient selection must be carefully carried out. Underlying chronic liver disease is exacerbated by this procedure, especially in patients with diminished liver reserve [10]. Several algorithms have been recently reported to predict HCC prognosis in an attempt to optimize chemoembolization treatments, but few data have been obtained from DEB-TACE procedures [11,12,13]. Moreover, there is also scarce information about the influence of post-DEB-TACE events on OS and hepatic decompensation.

A prior meta-analysis of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials for HCC reported that ascites is strongly linked to a worse outcome in intermediate/advanced BCLC stages [14].

Some authors have suggested that a time-dependent covariate analysis that includes all the rounds of DEB-TACE, clinically relevant events and subsequent therapies is needed to properly evaluate the factors that influence the survival of patients.

The aim of our study was to identify predictive factors for survival in HCC patients treated with DEB-TACE, taking into account the basal characteristics, the procedure, the response to treatment and the impact of events after the first DEB-TACE (DEB-TACE-1), in a time-dependent covariate analysis.

Methods

Patients

From October 2008 to October 2015, patients with HCC diagnosed according to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines who were selected for DEB-TACE were referred to a tertiary academic university hospital and were prospectively registered.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) HCC that was diagnosed in the early stage but was not eligible for resection, ablation or liver transplant; 2) HCC with an intermediate BCLC stage; 3) compensated cirrhosis with normal or mildly altered liver function, without ascites or encephalopathy at the time of DEB-TACE; 4) an asymptomatic status, with an ECOG performance status 0; and 5) approval for DEB-TACE after evaluation by the multidisciplinary tumour board. Portal thrombosis, impaired liver function, current decompensated cirrhosis, performance status > 0, extrahepatic disease and contraindication or impossibility for catheterization or chemoembolization were considered exclusion criteria. Patients included in clinical trials or awaiting liver transplantation for whom DEB-TACE was used as a bridge therapy were excluded.

Clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) was defined as the presence of prior cirrhosis decompensation, oesophageal or gastric varices or low platelet counts (lower than 100 × 109/L) [15] and early ascites as the appearance of ascites after the first round of DEB-TACE.

Clinical, biochemical and radiological examinations were performed at baseline and prior to every DEB-TACE procedure. No general sedation was used, and no antibiotic prophylaxis was indicated, except in patients with prior endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. If the prothrombin rate was lower than 50% or if the platelet count was less than 50 × 109/L, fresh-frozen plasma was administered and/or platelet infusion was performed. Pain during the procedure was individually managed, and patients were discharged 24 h later, unless complications were observed.

DEB-TACE procedure

Drug-eluting beads® were loaded with doxorubicin following the manufacturer’s instructions the day before the procedure. Particles that were 300–500 μm (μm) were used until March 2013, when these particles were replaced by 100–300-μm beads to further penetrate the tumour [16]. If embolization was not completely achieved unloaded microspheres were employed to complete the artery obstruction.

Selective angiography of the common hepatic artery was carried out as well as of the right and left hepatic arteries. A supraselective approach for tumour vessels was achieved by using a Progreat 2.7 (Terumo®) microcatheter with 0.21, 0.16 or 0.14 Terumo® microwires, and DC-Beads® were then injected. After angiographic control, the 4F catheter and the introducer were removed, and manual compression was applied.

Starting in February 2015, Cone-Beam-CT software (CBCT, Syngo DynaCT, Siemens®) with contrast injection was employed to help during vascular catheterization, especially if the nodule was not visible at basal angiography or was in intersegmental nodules, when lesions were proximal to the diaphragm and when extrahepatic vascularization was evaluated. Once the procedure was finished, CBCT without intraarterial contrast was used to evaluate embolization.

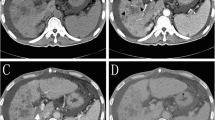

Follow-up

All patients received a clinical, analytical and radiological follow-up 6 weeks after each DEB-TACE procedure. Response to treatment was evaluated by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) according to the Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) criteria [17], and results were presented to the multidisciplinary tumour board. If partial response, stable disease or treatable progression were observed, a subsequent DEB-TACE was planned [18]. Patients with untreatable progression were evaluated for systemic therapy. Objective response (OR) was defined as the sum of complete response and partial response. The disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the OR as well as the stable disease rate.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as the median and interquartile range, and categorical variables are expressed as the count and proportion. Continuous quantitative variables were categorized according to the median value for the analysis. Differences between subgroups were evaluated with a Chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test and U-Mann Whitney, depending on the type of variable. A conventional p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Patient survival probability was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. OS was calculated from DEB-TACE-1 to death or to the end of follow-up for two periods: from baseline (t0), taking into account clinical, demographic and radiological data prior to DEB-TACE-1, and from 6 weeks after DEB-TACE-1 (t1), also considering complications and the radiological response to treatment. Variables with univariate significance (p < 0.10) and clinical relevance were included in the Cox proportional hazards model for the multivariable analysis with the forward selection method.

The factors associated with the development of early ascites were analysed, bearing in mind the baseline characteristics, the response to treatment and other complications. The time was censored at ascites development, death or the second DEB-TACE (DEB-TACE-2).

All calculations were performed with SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

An additional time-dependent covariate analysis was performed by using R (www.r-project.org) to identify factors associated with mortality. A backward method based on the Akaike information criteria was employed.

The protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (Approval No. 120/19). This prospective database has been retrospectively reviewed and because of the retrospective nature of the study consent retrieval was waived.

Results

From October 2008 to October 2015, 242 consecutive patients with HCC who were diagnosed according to EASL guidelines were referred for DEB-TACE, but only 216 of these patients met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics. The predominant aetiology of liver disease was alcohol (45%), followed by hepatitis C virus infection (36%). Most of the patients were BCLC-B (58%) and Child-Pugh class A 5 (64%). Sixty-one percent had oesophageal varices, 32% were on a low-salt diet and / or diuretic and 73% presented CSPH.

The median number of DEB-TACE sessions was 2 (IQR, 1–3), and a total of 443 procedures were performed (Fig. 1).

The median follow-up was 26.5 months, and follow-up was censored at death, loss to follow-up or the last visit (April 1, 2019).

Response to treatment

According to the mRECIST criteria at week 6 after DEB-TACE-1, complete response was achieved in 55 patients (26%), partial response in 97 patients (45%) and stable disease in 24 (11%). In contrast, 35 patients (16%) presented progressive disease after DEB-TACE-1. 35% of those migrated to BCLC-C stage. In 5 patients (2%), mRECIST was not available.

Follow-up and post-DEB-TACE events

During the follow-up, DEB-TACE was discontinued in 71 patients after the first session. Figure 1 shows the different causes for the discontinuation of DEB-TACE after the first or subsequent rounds. Post-procedure events within the first 90 days after DEB-TACE-1 are described in Supplementary Table 1. A total of 73 of 216 patients experienced post-DEB-TACE-1 events (33.7%): 23 patients (31.5%) experienced radiological events, 41 patients (56.2%) experienced clinical events and 9 patients (12.3%) experienced both clinical and radiological events. Ascites was the most frequent adverse event and was present in 27 patients.

At the end of follow-up, 27 patients were alive; 70 patients had moved to sorafenib and 9 to second-line regorafenib.

Overall survival

The median OS from DEB-TACE-1 was 27 months (95% confidence interval (CI), 24.193–29.807) (Fig. 2). The cumulative survival rates were 82, 58, 32 and 16% at 1, 2, 3 and 5 years, respectively.

. Univariate and multivariate analyses prior to DEB-TACE-1 (t0) and at 6 weeks after DEB-TACE-1 (t1) are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Supplementary Table 2 collects the variable values in t1.The independent factors associated with OS at t0 were tumor size < 36.5 mm (cut-off estimated by AUROC) 30 vs 22 months HR 0.72 (95% CI 0.53–0.98, p = 0.039), basal AFP < 100 ng/mL (arbitrary value) 29 vs 18 months HR 0.67 (95% CI 0.47–0.96, p = 0.029) and basal alkaline phosphatase < 108 IU/L (median value) 32 vs 24 months HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.47–0.88, p = 0.005). By contrast, the independent factors associated with OS at t1 were post-TACE albumin < 35 g/L (arbitrary cut-off) 22 vs 30 months HR 1.5 (95% CI 1.1–2.2, p = 0.02), post TACE AFP < 100 ng/mL (arbitrary cut-off) 29 vs 12 months HR 0.65 (95% CI 0.45–0.93, p = 0.02) and absence of development of ascites (28 vs 17 months, HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.27–0.68, p < 0.001). There were four additional models, 2 of them including objective response, detailed in Table 3.

Post-DEB-TACE events

The most important clinical event associated with shorter survival was the presence of ascites after DEB-TACE-1 (Fig. 3). Patients with ascites (n = 27) had a median OS of 17 months (95% CI, 8.566–25.434; p < 0.05); in contrast, patients without ascites had a median OS of 28 months (95% CI, 25.519–30.481). Cumulative survival rates at 1, 2, 3 and 5 years are shown in Fig. 3.

Baseline characteristics associated with the development of ascites are shown in Supplementary Table 3. History of ascites decompensation, haemoglobin and albumin were independently related to the development of early ascites (Table 4). The development of ascites after DEB-TACE was independent of the radiological response (the OR rate was similar in patients who developed ascites, indicating that this was not related to tumour progression, p = 0.13). Lastly, 9 patients recovered from hepatic decompensation and received DEB-TACE-2. The median time between decompensation and TACE retreatment was 52 days (range 181, IQR 46.5–132).

In the time-dependent covariate analysis, the variables that were independently associated with survival were basal alpha-fetoprotein (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.31–2.10; p < 0.001), time-dependent bilirubin (HR, 4.47; 95% CI, 1.80–11.09; p < 0.001) and time-dependent alkaline phosphatase (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.41–2.01; p < 0.001) (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 and Supplementary figure 1).

Discussion

Several publications have described the safety of DEB-TACE [6,7,8,9], but an in-depth analysis of the impact of adverse events on patient progression has not been examined. Our study determined that the development of early ascites was negatively related to the overall survival of compensated patients treated with DEB-TACE. This finding was related to low albumin, low haemoglobin and prior episodes of clinical ascites. The presence of significant portal hypertension and/or worse liver function might suggest that patients are predisposed to complications in chemoembolization procedures and to the consequent impairment in OS. Currently, the presence of CSPH precludes patients from undergoing surgical resection for HCC [19], but less attention has been paid to other loco-regional therapies. However, two studies have recently reported that CSPH is a major negative prognostic factor in patients treated with DEB-TACE [10, 20].

In our clinical practice, patients with previous decompensation that remain compensated for more than 6 months are not excluded for treatment with DEB-TACE. That is the case in 71 patients with alcohol related cirrhosis with a first episode of hepatic decompensation that are asymptomatic and compensated after alcohol withdrawal. It should be noted that the OS of this cohort was lower than that at other sites [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] (Supplementary Table 6), despite similar patient selection, supra-selective procedures and response to therapy. We speculate that although alcohol aetiology is not an independent predictor of survival, alcohol consumption can impair liver function due to acute-on-chronic liver failure [30] or alcoholic hepatitis [31, 32]. The poor prognosis of alcohol-related HCC has been specifically observed in some French cohort studies [33, 34] and in patients treated with Y90-radioembolization in the SORAMIC study [35]. Indeed, these patients had more comorbidities than those affected by hepatitis C, and in some cases, refused to undergo additional sessions of DEB-TACE. In our series, 6 patients presented a second primary tumour after DEB-TACE (1 pyriform sinus, 1 bladder, 1 colorectal and 3 lung cancers), and 13% of patients died from other causes that were not related to tumour progression or cirrhosis decompensation. Finally, some post-DEB-TACE events were handled out of the tertiary hospital, and the suboptimal care of cirrhosis complications could have influenced the survival of our patients.

Alkaline phosphatase has resulted as independent factors for survival following DEB-TACE-1, together with tumor size and AFP. This enzyme is a variation marker for embryonic stem cell and could indicate the proliferation of tumor cells, playing an important role in cell cycle regulation, cell proliferation and tumor formation. High levels of AP have been related to poor prognosis of HCC in different populations [36, 37].

This study had several weaknesses. This was an observational cohort study that was performed over many years, during which changes in the state-of-the-art technology occurred. However, the multidisciplinary core team and the main interventional radiologists did not change over the course of the study. Furthermore, neither the change in the DEB particles size (March 2013) nor the introduction of CBCT (February 2015) have influenced the objective response rate or the global overall survival (data not shown).

The second weakness was that no clinical events were identified in the time-dependent covariate analysis.

In contrast, the main advantage of this study was the prospective collection of a large number of patients who were treated with a homogeneous protocol and the collection of adverse effects after DEB-TACE, including asymptomatic radiological abnormalities.

Conclusions

In conclusion, adverse events reduce OS following DEB-TACE, especially when ascites is present. Although compensated chronic liver disease is a requirement for loco-regional therapy, the appearance of early ascites seems to be related to the history of prior ascites, lower haemoglobin levels and lower albumin. These factors could be relevant for properly selecting the best candidates for DEB-TACE when different therapeutic options are available.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- AP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- CBCT:

-

Cone-beam computed tomography

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CR:

-

Complete response

- CSPH:

-

Clinically significant portal hypertension

- CDR:

-

Disease control rate

- DEB-TACE:

-

Drug-eluting embolic chemoembolization

- EASL:

-

European Association for the Study of the Liver

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- mRECIST:

-

Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- OR:

-

Objective response

- OS:

-

Overall survival

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Fact Sheets by Population-Globocan-IARC [Internet]. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact sheets population.aspx..

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236.

Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723–50.

Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018 Mar 31;391(10127):1301–14.

Varela M, Real MI, Burrel M, et al. Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: efficacy and doxorubicin pharmacokinetics. J Hepatol. 2007;46:474–81.

Poon RT, Tso WK, Pang RW, et al. A phase I/II trial of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel intra-arterial drug-eluting bead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(9):1100–8.

Lammer J, Malagari K, Vogl T, et al. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:41–52.

Golfieri R, Giampalma E, Renzulli M, et al. Randomised controlled trial of doxorubicin-eluting beads vs. conventional chemoembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:255–64.

Kim NH, Lee T, Cho YK, Kim BI, Kim HJ. Impact of clinically evident portal hypertension on clinical outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transarterial chemoembolization. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33(7):1397–406.

Sieghart W, Hucke F, Pinter M, et al. The ART of decision making: retreatment with Transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2261–73.

Kadalayil L, Benini R, Pallan L, et al. A simple prognostic scoring system for patients receiving transarterial embolisation for hepatocellular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2565–70.

Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Naude S, et al. Retreatment with DEB-TACE: the ABCR SCORE, an aid to the decision-making process. J Hepatol. 2015;62(4):855–62.

Cabibbo G, Enea M, Attnasio M, Bruix J, Craxì A, Cammà C. A meta-analysis of survival rates of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;51(4):1274–83.

García-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):310–35.

Prajapati HJ, Xing M, Spivey JR, et al. Survival, efficacy, and safety of small versus large doxorubicin drug-eluting beads DEB-TACE chemoembolization in patients with unresectable HCC. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203(6):W706–14.

Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60.

Forner A, Gilabert M, Bruix J, Raoul JL. Treatment of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(9):525–35.

Berzigotti A, Reig M, Abraldes JG, Bosch J, Bruix J. Portal hypertension and the outcome of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in compensated cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2015;61(2):526–36.

Choi JW, Chung JW, Lee DH, et al. Portal hypertension is associated with poor outcome of transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(5):2184–93.

Malagari K, Pomoni M, Moschouris H, et al. Chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: five-year survival analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35(5):1119–28.

Burrel M, Reig M, Forner A, et al. Survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transarterial chemoembolisation (DEB-TACE) using drug eluting beads. Implications for clinical practice and trial design. J Hepatol. 2012;56(6):1330–5.

Terzi E, Terenzi L, Venerandi L, Croci L. The ART score is not effective to select patients for transarterial chemoembolization retreatment in an Italian series. Dig Dis. 2014;32(6):711–6.

Chen L, Ni CF, Chen SX, et al. A modified model for assessment for retreatment with Transarterial chemoembolization in Chinese hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(9):1288–97.

Facciorusso A, Mariani L, Sposito C, et al. Drug-eluting beads versus conventional chemoembolization for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(3):645–53.

Pipa-Muñiz M, Castells L, Pascual S, et al. The ART-SCORE is not an effective tool for optimizing patient selection for DEB-TACE retreatment. A multicentre Spanish study. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40(8):515–24.

Zhang YQ, Jiang LJ, Wen J, et al. Comparison of α-fetoprotein criteria and modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors for the prediction of overall survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after Transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(12):1654–61.

Biolato M, Gallusi G, Iavarone M, et al. Prognostic ability of BCLC-B subclassification in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing Transarterial chemoembolization. Ann Hepatol. 2018;17(1):110–8.

Sánchez-Delgado J, Vergara M, Machlab S, et al. Analysis of survival and prognostic factors in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in Spanish patients with drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30(12):1453–60.

Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginés P, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–37.

Shah ND, Ventura-Cots M, Abraldes JG, et al. Alcohol related Liver Disease is Rarely Detected at Early Stages Compared With Liver Diseases of Other Etiologies Worldwide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;S1542–3565(19):30073–4.

Marot A, Henrion J, Knebel JF, Moreno C, Deltenre P. Alcoholic liver disease confers a worse prognosis than HCV infection and non-alcoholic fattyliver disease among patients with cirrhosis: an observational study. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186715.

Adhoute X, Pénaranda G, Raoul JL, et al. Barcelona clinic liver cancer nomogram and others staging/scoring systems in a French hepatocellular carcinoma cohort. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(14):2545–55.

Collette S, Bonnetain F, Paoletti X, et al. Prognosis of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of three staging systems in two French clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(6):1117–26.

Ricke J, Klümpen HJ, Amthauer H, et al. Impact of combined selective internal radiation therapy and sorafenib on survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2019;71:1164–74.

Chen ZH, Zhang XP, Cai XR, et al. The predictive value of albumin-to-alkaline phosphatase ratio for overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with trans-catheter arterial chemoembolization therapy. J Cancer. 2018;9(19):3467–78.

Wu X, Chen R, Zheng W, et al. Comprehensive analysis of factors affecting clinical response and short-term survival to drug-eluting bead Transarterial chemoembolization for treatment in patients with liver Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:1533033818759878.

Acknowledgements

Susana Díaz-Coto and Pablo Martínez-Camblor (statistical support).

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design of the study: MV and MP; data collection: MP, SS, AM, CAN, MLGD, VC, JER, FV; statistical analysis: MP, MR, MV; analysing the results and writing of article: MP, SS, AM, JER, SMCG, MR, MV. All authors approved the last version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (Approval No. 120/19). No specific individual consent was obtained regarding the publication of data due to the retrospective nature of the publication.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Pipa-Muñiz M, Sanmartino S, Mesa A, Cadahía V, Rodríguez JE, Vega F, and Costilla-García SM: none. Álvarez Navascués C: speaking fees and advisory roles for Gilead, Abbvie, and Intercept. González-Dieguez ML: speaker fees from Gilead, Abbvie and Novartis and consultancy fees from Gilead. Manuel Rodríguez M: speaking fees and advisory fees from Gilead, Abbvie, Intercept, and MSD. Varela M: speaker fees from Bayer and Gilead; consultancy fees from Roche, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, SIRTEX, Bayer, IPSEN, and BTG-Boston.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Supplementary Figure 1

. probability of death in an average individual.

Additional file 2 Supplementary Table 1

. Post-DEB-TACE events.

Additional file 3 Supplementary Table 2

. Variable values in the pos-TACE time (t1).

Additional file 4 Supplementary Table 3

. Baseline characteristics associated with the development of early ascites.

Additional file 5 Supplementary Table 4.

Time dependent-covariate analysis. Univariate model.

Additional file 6 Supplementary Table 5

. Time-dependent multivariate analysis.

Additional file 7 Supplementary Table 6

. Cohort studies on TACE/DEB-TACE focused on alcohol etiology and survival.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pipa-Muñiz, M., Sanmartino, S., Mesa, A. et al. The development of early ascites is associated with shorter overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with drug-eluting embolic chemoembolization. BMC Gastroenterol 20, 166 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01307-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01307-x