Abstract

Background

In the general practice setting screening, brief intervention and counselling have been shown to be effective in the reduction of problem alcohol use. This study aimed to explore Irish general practitioners’ (GPs) current practice of and attitudes towards the management of problem alcohol use.

Methods

An online survey was emailed, with one email reminder, to 1750 general/family practitioners who were members of the Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP) and for whom an active email address was available. Overall, 476 completed questionnaires were received representing a 27.2% response rate.

Results

Two-thirds of the respondents reported that they have managed patients for problem alcohol use and related issues in the past year. The majority, 96%, of respondents indicated that they initiate conversations around alcohol even when the patient does not do so. Almost two thirds of GPs stated that they use structured brief intervention when talking to patients about their alcohol intake and circa 85% reported that they provide some form of counselling in relation to reducing alcohol consumption. While more than two out of three GPs felt prepared when counselling patients in relation to alcohol consumption, almost half considered they are ineffective in helping patients to reduce alcohol consumption. One third of GPs advised that they did not have access to an addiction counsellor.

Conclusions

GPs in this survey reported widespread experience of screening and intervention, however, many still felt ineffective. In order to maximise the potential impact of GPs, a clearer understanding is required of what interventions are effective in different scenarios. Furthermore, GPs are only part of the solution in terms of addressing alcohol consumption. The services available in the broader health care system and Government alcohol related policy needs to further support GPs and patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alcohol use disorders are as common and as costly as both depression and coronary heart disease [1]. Alcohol consumption is now linked to more than 60 medical conditions [2]. Alcohol problems hinder efforts towards the assessment and treatment of these conditions [2] while also increasing risky behaviours [3].

Irish residents rank among the highest consumers of alcohol and of binge drinkers in Europe showing increasing rates while other countries are showing reductions [1, 4, 5]. Alcohol use is embedded within the cultural fabric of the nation, receiving a level of accommodation extended to no other drug [6, 7].

The harm experienced both by the individual and by those in their personal or social vicinity as a result of problem alcohol use in Ireland was previously highlighted [8].Taking just two examples, alcohol was found to be a contributory factor in 36.5% of all fatal road accidents, while it was also described as a main trigger in 34% of domestic violence cases [9].

The high level of alcohol consumption in Ireland and the concomitant harm it produces is imposing substantial tangible costs upon the Irish Exchequer with the main burden being placed upon the health care and criminal justice systems. Based upon an assessment of data from 2007, the estimated overall annual cost of problem alcohol use is €3.7 billion, accounting for 1.9% of GDP for that year. Such tangible costs are above the European average for the percentage of GDP spent on alcohol misuse (1.3%) and are at the higher end of this cost range within Europe (0.9 to 2.4%) [10].

Due to increased population contact and as part of a health promotion role, primary care settings are in a unique position for alcohol identification screening and intervention [11,12,13,14].

The identification and assessment of those who are at risk of, or already experiencing alcohol-related difficulties is of fundamental importance. It is accepted that clinical interviewing has outperformed the chemical or biological marker forms of assessment [15]. Upon consideration of a number of reviews of brief screening tools, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and CAGE questionnaire (the name ‘CAGE’ is an acronym of the four questions contained in this tool) are the most widely used and validated screening tools in primary care settings [16, 17].

Brief interventions within primary care settings, typically following screening, are valuable in the management of individuals with alcohol-related problems [14, 18]. While, it is acknowledged that there may be confusion over what constitutes ‘brief intervention’, it is generally accepted to be more than providing feedback on risk level and the provision of a leaflet only [19].

The evidence indicates that brief intervention in primary care settings can lower levels of alcohol consumption [20,21,22,23,24] with the advantages of low associated costs [25, 26] and limited added time for practitioners [27,28,29,30]. It has also been demonstrated that behavioural counselling can reduce alcohol consumption [31,32,33]. As many as 20% of patients in Ireland have been shown to have unhealthy drinking patterns [6]. The evidence suggests that brief intervention can help to reduce drinking levels across all patient groups [3].

The ICGP has conducted much work in this area with guidelines, courses, e-learning modules and research having been embarked upon since 2000 [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. This study aimed to explore Irish GPs current practice of and attitudes towards the management of problem alcohol use.

Methods

The ICGP is the professional body for GPs in Ireland representing over 90% of GPs in Ireland. An online survey via SurveyMonkey was emailed, with one email reminder, to 1750 ICGP members for whom email addresses were available and up to date.

The questionnaire (shown in Additional file 1) was designed by the project advisory group and included (with permission) questions from a similar study -the Optimizing Delivery of Health Care Interventions (ODHIN) project [42] in order to permit international comparison. The ODHIN project involved nine European countries and aimed to improve the delivery of health care interventions. It focused on the implementation of identification and brief intervention programmes related to alcohol consumption. Analysis was undertaken using descriptive statistics with SPSS (Version 21).

Results

Overall, 476 completed questionnaires were received giving a 27.2% response rate. Respondent demographics and comparison to the ICGP member population are shown in Table 1. Over three-quarters (77.7%) were engaged in seven or more general practice clinical sessions per week and 62.5% saw more than 100 patients weekly.

Overall 42.7% reported that they screened for alcohol misuse among their patients with 42.4% of these using a specific screening tool, with that employed most often being the CAGE questionnaire (88.9%). Almost three-quarters of the respondents used the screening tool (71.4%) in all lifestyle consultations and 87.8% to 97.9% in situations of specific concern/relevance (Fig. 1). Over half (55.3%) used the tool randomly in consultations even when lifestyle or specific concerns were not present.

Of those who responded, 30.5% stated that in the scenario where the patient does not mention alcohol, they ask about alcohol consumption all or most of the time, 66.4% do so some of the time while the remaining 4.1% rarely or never do so.

Almost all GPs (96.3%) felt they have the right to ask patients about their drinking when necessary and 79.2% felt that their patients consider they have a right to do so. Overall, 86.3% agreed that they can appropriately advise their patients about drinking and its effects and 67.7% agreed that they know enough about the causes of problem drinking to carry out their role in this area (Table 2).

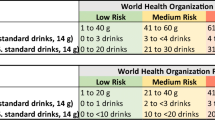

Two-thirds of GPs who responded reported that they have managed patients for hazardous drinking and alcohol dependency and related alcohol problems in the last year. Almost two-thirds (62.8%) reported using structured brief intervention when talking to patients about their alcohol intake and 84.7% reported providing some form of counselling in relation to reducing alcohol consumption. When treating a patient with an alcohol problem, 15.5% of GPs recommended total abstinence, 16.7% a reduction in intake of alcohol and 67.8% reported that they did not have a pre-determined approach but adapted this to suit the patient. Over half (52.7%) of GPs were applying weekly alcohol consumption limit guidelines (17 and 11 standard drinks per week for males and females respectively [37]) on which to base their advice to patients. A further 28.1% used a cut off which was lower than that indicated in the guidelines while 19.2% used a cut-off higher than recommended weekly limits.

Overall, 63.2% of GPs who responded had direct access to addiction counsellors while 32.6% had direct access to a residential addiction service. Four-fifths (79.6%) of the respondents referred a patient in the past year to the psychiatry service (including addiction counsellors).

While more than two out of three GPs felt prepared when counselling patients in relation to alcohol consumption, almost half (49.7%) considered they were ineffective in helping patients to reduce alcohol consumption (Fig. 2). Respondents to this survey were very positive with regard to the potential effectiveness of GPs in reducing patients’ alcohol consumption with 32.2% considering they would be very effective and 58.5% effective if given adequate information and training. The remaining 9.3% thought they would be ineffective.

Discussion

Main findings

Almost all GPs who responded to this survey initiated conversations around alcohol even when the patient did not do so. The majority of GPs reported that they have managed patients for hazardous drinking and alcohol dependency and related alcohol problems in the past year. When treating a patient with an alcohol problem, the majority of respondents indicated their approach to abstinence was patient dependent. The latter likely reflects the GPs’ knowledge of their patients, taking account of the patient’s medical and family history and support networks. While more than two out of three GPs felt prepared when counselling patients in relation to alcohol consumption, almost half considered they were ineffective in helping patients to reduce alcohol consumption. This survey highlighted the disparity of access to support services for GPs and their patients with alcohol problems with some who did not have access to an addiction counsellor.

Limitations of the study

This response rate, which may be considered as low, is in fact typical of surveys of physicians internationally [43, 44]. Low response rates raise concerns about bias and it could be the case that such a survey results in under or over estimates. However, the concern of bias is somewhat negated by the distribution across all demographic descriptors and as the demographic distribution was representative of all ICGP members [45].

Interpretation of findings in the context of existing evidence

In Ireland, more than half (54.3%) of those aged 18–75 years who consume alcohol are classified as harmful drinkers [46]. GPs in Ireland at an individual level have significant experience in dealing with alcohol related problems, given the extent to which their patients experience ongoing difficulties and harm from alcohol consumption.

In the general practice setting, screening [16, 47,48,49,50], brief intervention [14, 20, 21, 24], and counselling [31, 32] for early problems related to alcohol have been shown to be effective in the reduction of harmful and hazardous drinking. The results of our survey showed that the majority of GPs in this survey reported using structured brief intervention when talking to patients about their alcohol intake and most provided some form of counselling in relation to reducing alcohol consumption.

Similar to the findings from the ODHIN study, conducted in nine other European countries, GPs in our survey called for better training and infrastructure [42].

Over half of the respondents felt they were ineffective in terms of helping patients to reduce alcohol consumption. Many factors may contribute to this and not least the fact that we need to better understand how, why, when and what brief interventions work [51,52,53]. Furthermore, our respondents may be accurate in terms of patient acceptance of being asked about their alcohol consumption, as found elsewhere [54], however, the impact of intervention may be limited if patients do not view their drinking as problematic [55] and it may not lead to increased use of alcohol-related care [51].

Implications for research and practice

Other recent research has shown that the documentation of alcohol consumption status and of the interventions undertaken is poor in Irish general practice [56] and this may have implications for effectiveness in terms of follow-up as shown in other scenarios [57, 58]. We did not look at patient records in this study but further research on the level of brief intervention, its recording and the resultant patient outcomes in the Irish setting would be valuable. However, screening and intervention by health professionals is only one aspect in terms of addressing the impact of alcohol consumption on our health, community and associated alcohol related costs [51, 53, 59]. A full review of policies is required and necessitates collaboration between Government departments and agencies and across the full health system [51, 53, 59].

Conclusions

The impact of interventions in the general practice setting may be limited in a country such as Ireland with high levels of alcohol consumption, given that acceptance and potentially a lack of recognition among patients that their consumption level is problematic. GPs in this survey reported widespread experience of screening and intervention, however, many still felt ineffective. In order to maximise the potential impact of GPs, a clearer understanding is required of what interventions are effective in different scenarios. Furthermore, GPs are only part of the solution in terms of addressing alcohol consumption. The services available in the broader health care system and Government alcohol related policy needs to further support GPs and patients.

Abbreviations

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- CAGE:

-

The CAGE questionnaire, the name of which is an acronym of its four questions, is a widely used screening test for problem drinking and potential alcohol problems

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HSE:

-

Health Service Executive

- ICGP:

-

Irish College of General Practitioners

- ODHIN:

-

Optimizing Delivery of Health Care Interventions

- OECD:

-

The organisation for economic co-operation and development

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

Saitz R, Horton NJ, Sullivan LM, Moskowitz MA, Samet JH. Addressing alcohol problems in primary care: a cluster randomized, controlled trial of a systems intervention. The screening and intervention in primary care (SIP) study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):372–82.

Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492–501.

Corte CM, Sommers MS. Alcohol and risky behaviors. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2005;23:327–60.

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health, 2014. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/

OECD. OECD Health Statistics 2017. http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm

O'Dwyer P. The Irish and substance abuse. In: Straussner A, Lala S, editors. Ethnocultural factors in substance abuse treatment. New York: the Guildford press; 2001. p. 199–215.

Morgan K, McGee H, Dicker P, Brugha R, Ward M, Shelley E, Van Lente E, Harrington J, Barry M, Perry I, Watson DSLÁN. Survey of lifestyle, attitudes and nutrition in Ireland. In: Alcohol use in Ireland: a profile of drinking patterns and alcohol-related harm from SLÁN 2007, Department of Health and Children. Dublin: The Stationery Office; 2007. p. 2009.

Hope A. Alcohol’s harm to others in Ireland. Dublin: Health service Executive; 2014.

Hope A. Alcohol-related harm in Ireland. Dublin: Health service executive, alcohol implementation Group; 2008.

Byrne S. Costs to Society of Problem Alcohol use in Ireland. Dublin: Health service Executive; 2010.

Owens L, Gilmore IT, Pirmohamed M. General practice nurses' knowledge of alcohol use and misuse: a questionnaire survey. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35(3):259–62.

Johansson K, Bendtsen P, Akerlind I. Early intervention for problem drinkers: readiness to participate among general practitioners and nurses in Swedish primary health care. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(1):38–42.

Johansson K, Bendtsen P, Akerlind I. Factors influencing GPs' decisions regarding screening for high alcohol consumption: a focus group study in Swedish primary care. Public Health. 2005;119(9):781–8.

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MGAUDIT. The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary Health care. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2001.

Chan-Pensley E. Alcohol-use disorders identification test: a comparison between paper and pencil and computerized versions. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34(6):882–5.

Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O'Connor PG. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(13):1977–89.

Maisto SA, Saitz R. Alcohol use disorders: screening and diagnosis. Am J Addict. 2003;12(Suppl 1):S12–25.

McAuley A, Watson M, Stewart D, Sheridan J, Fitzgerald N, Dhital R, et al. Increasing capacity in alcohol screening and brief interventions: a role for community pharmacy? Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland; 2012.

Heather N, Lavoie D, Morris J. Clarifying alcohol brief interventions: 2013 update. The Alcohol Academy; 2013 http://ranzetta.typepad.com/files/clarifying-alcohol-brief-interventions-2013-update.pdf

Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD004148.

Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, Pienaar E, Schlesinger C, Campbell F, et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(3):301–23.

Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97(3):279–92.

Ballesteros J, Duffy JC, Querejeta I, Arino J, Gonzalez-Pinto A. Efficacy of brief interventions for hazardous drinkers in primary care: systematic review and meta-analyses. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(4):608–18.

Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–95.

Broskowski A, Smith S. Estimating the cost of Preventive Services in Mental Health and Substance Abuse under Managed Care Rockville. MD: U.S.: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2001.

Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):143–52.

Kahan M, Wilson L, Becker L. Effectiveness of physician-based interventions with problem drinkers: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(6):851–9.

Coffield AB, Maciosek MV, McGinnis JM, Harris JR, Caldwell MB, Teutsch SM, et al. Priorities among recommended clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(1):1–9.

Chisholm D, Rehm J, Van Ommeren M, Monteiro M. Reducing the global burden of hazardous alcohol use: a comparative cost-effectiveness analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(6):782–93.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):554–6.

Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):557–68.

Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, Brown JM, Brownley KA, Council CL, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(9):645–54.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guildford Press; 2002.

Healthcare European Project on Alcohol (PHEPA) EU Study 2003-2004: Irish team report. ICGP: December 2004. http://www.icgp.ie/go/library/catalogue/item?spId=D3127C94-4516-4FC8-800DD3019880D645

Promoting Alcohol Reduction - Addressing Alcohol Misuse in Primary Care. https://www.icgp-education.ie/mod/page/view.php?id=3495.

Alcohol Aware Practice Service Initiative April 2005 - March 2006: final report - August 2006. https://www.icgp.ie/go/library/catalogue/item/FC149777-F554-4D67-AD8AF8EA30639111.

Anderson R. Helping patients with alcohol problems: a guide for primary care staff. Dublin: Irish College of General Practitioners, Quality in practice committee; 2009.

No external funding was received for this project. Finegan P, O'Riordan M. Prevention of alcohol related problems in Ireland - ICGP position paper. ICGP: 2012. http://www.icgp.ie/go/library/catalogue/item?spId=7BEA8A08-F5A7-4592-99EFEE3FA8EC7DDA

Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Primary Care Staff Quick Reference Guide. www.icgp.ie/QRGalcohol.

Substance Misuse and Associated Health Problems Certificate Course. ICGP: 2015. http://www.icgp.ie/go/courses/courses/CERTSUBMISUSE

Clinical Focus: Alcohol problems - update on treatment. ICGP: 2015 http://www.icgp.ie/go/library/catalogue/item?spId=7A53106D-B661-F9AA-C7F0C53CC57CEA6F

Wojan M. ODHIN (Optimizing Delivery of Health Care Interventions): Deliverable 4.1: Survey of attitudes and managing alcohol problems in general practice in Europe – Final Report. 2014; Available at: http://www.odhinproject.eu.

Grava-Gubin I, Scott S. Effects of various methodologic strategies. Survey response rates among Canadian physicians and physicians in-training. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1424–30.

Van Geest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL. Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30(4):303–21.

Irish College of General Practitioners Membership Statistics Irish College of General Practitioners; 2016.

Long J, Mongan D. Alcohol consumption in Ireland 2013: Results of a national alcohol diary survey. Dublin: Health Research Board; 2014.

Berner MM, Kriston L, Bentele M, Harter M. The alcohol use disorders identification test for detecting at-risk drinking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007 May;68(3):461–73.

Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007 Feb;31(2):185–99.

Dhalla S, Kopec JA. The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: a review of reliability and validity studies. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(1):33–41.

Hodgson RJ, John B, Abbasi T, Hodgson RC, Waller S, Thom B, et al. Fast screening for alcohol misuse. Addict Behav. 2003;28(8):1453–63.

McCambridge J, Saitz R. Rethinking brief interventions for alcohol in general practice. BMJ. 2017;356:j116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j116.

Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2015;110(9):1404–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12950.

Heather N. Can screening and brief intervention lead to population-level reductions in alcohol-related harm? Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-7-15.

Nilsen P, Bendtsen P, McCambridge J, Karlsson N, Dalal K. When is it appropriate to address patients’ alcohol consumption in health care—national survey of views of the general population in Sweden. Addict Behav 2012;36(11):1211–1216. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.024 .

Quirk A, MacNeil V, Dhital R, Whittlesea C, Norman I, McCambridge J. Qualitative process study of community pharmacist brief alcohol intervention effectiveness trial: can research participation effects explain a null finding? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.023.

O’Regan A, Cullen W, Hickey L, Meagher D, Hannigan A. Is problem alcohol use being detected and treated in Irish general practice? BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(30). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0718-5.

De Muylder R, Lorant V, Paulus D, Nackers F, Jeanjean M, Boland B. Obstacles to cardiovascular prevention in general practice. Vol. 59, Acta Cardiol 2004:119–125.

Lee MJ, Oza B, Pakianathan M, Hegazi A. Making every contact count: improving the assessment of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men using a structured proforma. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(1):48.

Giesbrecht N, Wettlaufer A, Simpson S, April N, Asbridge M, Cukier S, Mann RE, McAllister J, Murie A, Pauley C, Plamondon L, Stockwell T, Thomas G, Thompson K, Vallance K. Strategies to reduce alcohol-related harms and costs in Canada: a comparison of provincial policies. IJADR. 2016;5(2):33–45. https://doi.org/10.7895/ijadr.v5i2.221.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the assistance of members of the ICGP who participated in the survey and hence informed this work.

Funding

No external funding was received for this project.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset related to this work is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC designed the questionnaire, collected the data, analysed the data, prepared the paper and viewed the final version of the paper. PF initiated the research project, contributed to the questionnaire design, contributed to the paper and viewed the final version of the paper. MOR contributed to the questionnaire design, contributed to the paper and viewed the final version of the paper.

All authors have given final approval of this version of the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted from the Irish College of General Practitioners' Research Ethics Committee .

Participants were informed that completion and return of the anonymous questionnaire represented implied consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as no individual data reported.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Study questionnaire. Questionnaire_GP experience of managing problem alcohol use. (PDF 275 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, C., Finegan, P. & O’Riordan, M. An online survey of Irish general practitioner experience of and attitude toward managing problem alcohol use. BMC Fam Pract 19, 200 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0889-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0889-0