Abstract

Background

Systematic literature searching is recognised as a critical component of the systematic review process. It involves a systematic search for studies and aims for a transparent report of study identification, leaving readers clear about what was done to identify studies, and how the findings of the review are situated in the relevant evidence.

Information specialists and review teams appear to work from a shared and tacit model of the literature search process. How this tacit model has developed and evolved is unclear, and it has not been explicitly examined before.

The purpose of this review is to determine if a shared model of the literature searching process can be detected across systematic review guidance documents and, if so, how this process is reported in the guidance and supported by published studies.

Method

A literature review.

Two types of literature were reviewed: guidance and published studies. Nine guidance documents were identified, including: The Cochrane and Campbell Handbooks. Published studies were identified through ‘pearl growing’, citation chasing, a search of PubMed using the systematic review methods filter, and the authors’ topic knowledge.

The relevant sections within each guidance document were then read and re-read, with the aim of determining key methodological stages. Methodological stages were identified and defined. This data was reviewed to identify agreements and areas of unique guidance between guidance documents. Consensus across multiple guidance documents was used to inform selection of ‘key stages’ in the process of literature searching.

Results

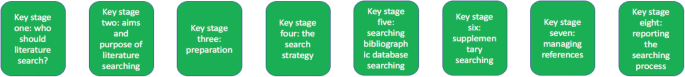

Eight key stages were determined relating specifically to literature searching in systematic reviews. They were: who should literature search, aims and purpose of literature searching, preparation, the search strategy, searching databases, supplementary searching, managing references and reporting the search process.

Conclusions

Eight key stages to the process of literature searching in systematic reviews were identified. These key stages are consistently reported in the nine guidance documents, suggesting consensus on the key stages of literature searching, and therefore the process of literature searching as a whole, in systematic reviews. Further research to determine the suitability of using the same process of literature searching for all types of systematic review is indicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Systematic literature searching is recognised as a critical component of the systematic review process. It involves a systematic search for studies and aims for a transparent report of study identification, leaving review stakeholders clear about what was done to identify studies, and how the findings of the review are situated in the relevant evidence.

Information specialists and review teams appear to work from a shared and tacit model of the literature search process. How this tacit model has developed and evolved is unclear, and it has not been explicitly examined before. This is in contrast to the information science literature, which has developed information processing models as an explicit basis for dialogue and empirical testing. Without an explicit model, research in the process of systematic literature searching will remain immature and potentially uneven, and the development of shared information models will be assumed but never articulated.

One way of developing such a conceptual model is by formally examining the implicit “programme theory” as embodied in key methodological texts. The aim of this review is therefore to determine if a shared model of the literature searching process in systematic reviews can be detected across guidance documents and, if so, how this process is reported and supported.

Methods

Identifying guidance

Key texts (henceforth referred to as “guidance”) were identified based upon their accessibility to, and prominence within, United Kingdom systematic reviewing practice. The United Kingdom occupies a prominent position in the science of health information retrieval, as quantified by such objective measures as the authorship of papers, the number of Cochrane groups based in the UK, membership and leadership of groups such as the Cochrane Information Retrieval Methods Group, the HTA-I Information Specialists’ Group and historic association with such centres as the UK Cochrane Centre, the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Coupled with the linguistic dominance of English within medical and health science and the science of systematic reviews more generally, this offers a justification for a purposive sample that favours UK, European and Australian guidance documents.

Nine guidance documents were identified. These documents provide guidance for different types of reviews, namely: reviews of interventions, reviews of health technologies, reviews of qualitative research studies, reviews of social science topics, and reviews to inform guidance.

Whilst these guidance documents occasionally offer additional guidance on other types of systematic reviews, we have focused on the core and stated aims of these documents as they relate to literature searching. Table 1 sets out: the guidance document, the version audited, their core stated focus, and a bibliographical pointer to the main guidance relating to literature searching.

Once a list of key guidance documents was determined, it was checked by six senior information professionals based in the UK for relevance to current literature searching in systematic reviews.

Identifying supporting studies

In addition to identifying guidance, the authors sought to populate an evidence base of supporting studies (henceforth referred to as “studies”) that contribute to existing search practice. Studies were first identified by the authors from their knowledge on this topic area and, subsequently, through systematic citation chasing key studies (‘pearls’ [1]) located within each key stage of the search process. These studies are identified in Additional file 1: Appendix Table 1. Citation chasing was conducted by analysing the bibliography of references for each study (backwards citation chasing) and through Google Scholar (forward citation chasing). A search of PubMed using the systematic review methods filter was undertaken in August 2017 (see Additional file 1). The search terms used were: (literature search*[Title/Abstract]) AND sysrev_methods[sb] and 586 results were returned. These results were sifted for relevance to the key stages in Fig. 1 by CC.

Extracting the data

To reveal the implicit process of literature searching within each guidance document, the relevant sections (chapters) on literature searching were read and re-read, with the aim of determining key methodological stages. We defined a key methodological stage as a distinct step in the overall process for which specific guidance is reported, and action is taken, that collectively would result in a completed literature search.

The chapter or section sub-heading for each methodological stage was extracted into a table using the exact language as reported in each guidance document. The lead author (CC) then read and re-read these data, and the paragraphs of the document to which the headings referred, summarising section details. This table was then reviewed, using comparison and contrast to identify agreements and areas of unique guidance. Consensus across multiple guidelines was used to inform selection of ‘key stages’ in the process of literature searching.

Having determined the key stages to literature searching, we then read and re-read the sections relating to literature searching again, extracting specific detail relating to the methodological process of literature searching within each key stage. Again, the guidance was then read and re-read, first on a document-by-document-basis and, secondly, across all the documents above, to identify both commonalities and areas of unique guidance.

Results and discussion

Our findings

We were able to identify consensus across the guidance on literature searching for systematic reviews suggesting a shared implicit model within the information retrieval community. Whilst the structure of the guidance varies between documents, the same key stages are reported, even where the core focus of each document is different. We were able to identify specific areas of unique guidance, where a document reported guidance not summarised in other documents, together with areas of consensus across guidance.

Unique guidance

Only one document provided guidance on the topic of when to stop searching [2]. This guidance from 2005 anticipates a topic of increasing importance with the current interest in time-limited (i.e. “rapid”) reviews. Quality assurance (or peer review) of literature searches was only covered in two guidance documents [3, 4]. This topic has emerged as increasingly important as indicated by the development of the PRESS instrument [5]. Text mining was discussed in four guidance documents [4, 6,7,8] where the automation of some manual review work may offer efficiencies in literature searching [8].

Agreement between guidance: Defining the key stages of literature searching

Where there was agreement on the process, we determined that this constituted a key stage in the process of literature searching to inform systematic reviews.

From the guidance, we determined eight key stages that relate specifically to literature searching in systematic reviews. These are summarised at Fig. 1. The data extraction table to inform Fig. 1 is reported in Table 2. Table 2 reports the areas of common agreement and it demonstrates that the language used to describe key stages and processes varies significantly between guidance documents.

For each key stage, we set out the specific guidance, followed by discussion on how this guidance is situated within the wider literature.

Key stage one: Deciding who should undertake the literature search

The guidance

Eight documents provided guidance on who should undertake literature searching in systematic reviews [2, 4, 6,7,8,9,10,11]. The guidance affirms that people with relevant expertise of literature searching should ‘ideally’ be included within the review team [6]. Information specialists (or information scientists), librarians or trial search co-ordinators (TSCs) are indicated as appropriate researchers in six guidance documents [2, 7,8,9,10,11].

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

The guidance is consistent with studies that call for the involvement of information specialists and librarians in systematic reviews [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] and which demonstrate how their training as ‘expert searchers’ and ‘analysers and organisers of data’ can be put to good use [13] in a variety of roles [12, 16, 20, 21, 24,25,26]. These arguments make sense in the context of the aims and purposes of literature searching in systematic reviews, explored below. The need for ‘thorough’ and ‘replicable’ literature searches was fundamental to the guidance and recurs in key stage two. Studies have found poor reporting, and a lack of replicable literature searches, to be a weakness in systematic reviews [17, 18, 27, 28] and they argue that involvement of information specialists/ librarians would be associated with better reporting and better quality literature searching. Indeed, Meert et al. [29] demonstrated that involving a librarian as a co-author to a systematic review correlated with a higher score in the literature searching component of a systematic review [29]. As ‘new styles’ of rapid and scoping reviews emerge, where decisions on how to search are more iterative and creative, a clear role is made here too [30].

Knowing where to search for studies was noted as important in the guidance, with no agreement as to the appropriate number of databases to be searched [2, 6]. Database (and resource selection more broadly) is acknowledged as a relevant key skill of information specialists and librarians [12, 15, 16, 31].

Whilst arguments for including information specialists and librarians in the process of systematic review might be considered self-evident, Koffel and Rethlefsen [31] have questioned if the necessary involvement is actually happening [31].

Key stage two: Determining the aim and purpose of a literature search

The guidance

The aim: Five of the nine guidance documents use adjectives such as ‘thorough’, ‘comprehensive’, ‘transparent’ and ‘reproducible’ to define the aim of literature searching [6,7,8,9,10]. Analogous phrases were present in a further three guidance documents, namely: ‘to identify the best available evidence’ [4] or ‘the aim of the literature search is not to retrieve everything. It is to retrieve everything of relevance’ [2] or ‘A systematic literature search aims to identify all publications relevant to the particular research question’ [3]. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual was the only guidance document where a clear statement on the aim of literature searching could not be identified. The purpose of literature searching was defined in three guidance documents, namely to minimise bias in the resultant review [6, 8, 10]. Accordingly, eight of nine documents clearly asserted that thorough and comprehensive literature searches are required as a potential mechanism for minimising bias.

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

The need for thorough and comprehensive literature searches appears as uniform within the eight guidance documents that describe approaches to literature searching in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Reviews of effectiveness (of intervention or cost), accuracy and prognosis, require thorough and comprehensive literature searches to transparently produce a reliable estimate of intervention effect. The belief that all relevant studies have been ‘comprehensively’ identified, and that this process has been ‘transparently’ reported, increases confidence in the estimate of effect and the conclusions that can be drawn [32]. The supporting literature exploring the need for comprehensive literature searches focuses almost exclusively on reviews of intervention effectiveness and meta-analysis. Different ‘styles’ of review may have different standards however; the alternative, offered by purposive sampling, has been suggested in the specific context of qualitative evidence syntheses [33].

What is a comprehensive literature search?

Whilst the guidance calls for thorough and comprehensive literature searches, it lacks clarity on what constitutes a thorough and comprehensive literature search, beyond the implication that all of the literature search methods in Table 2 should be used to identify studies. Egger et al. [34], in an empirical study evaluating the importance of comprehensive literature searches for trials in systematic reviews, defined a comprehensive search for trials as:

-

a search not restricted to English language;

-

where Cochrane CENTRAL or at least two other electronic databases had been searched (such as MEDLINE or EMBASE); and

-

at least one of the following search methods has been used to identify unpublished trials: searches for (I) conference abstracts, (ii) theses, (iii) trials registers; and (iv) contacts with experts in the field [34].

Tricco et al. (2008) used a similar threshold of bibliographic database searching AND a supplementary search method in a review when examining the risk of bias in systematic reviews. Their criteria were: one database (limited using the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (HSSS)) and handsearching [35].

Together with the guidance, this would suggest that comprehensive literature searching requires the use of BOTH bibliographic database searching AND supplementary search methods.

Comprehensiveness in literature searching, in the sense of how much searching should be undertaken, remains unclear. Egger et al. recommend that ‘investigators should consider the type of literature search and degree of comprehension that is appropriate for the review in question, taking into account budget and time constraints’ [34]. This view tallies with the Cochrane Handbook, which stipulates clearly, that study identification should be undertaken ‘within resource limits’ [9]. This would suggest that the limitations to comprehension are recognised but it raises questions on how this is decided and reported [36].

What is the point of comprehensive literature searching?

The purpose of thorough and comprehensive literature searches is to avoid missing key studies and to minimize bias [6, 8, 10, 34, 37,38,39] since a systematic review based only on published (or easily accessible) studies may have an exaggerated effect size [35]. Felson (1992) sets out potential biases that could affect the estimate of effect in a meta-analysis [40] and Tricco et al. summarize the evidence concerning bias and confounding in systematic reviews [35]. Egger et al. point to non-publication of studies, publication bias, language bias and MEDLINE bias, as key biases [34, 35, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Comprehensive searches are not the sole factor to mitigate these biases but their contribution is thought to be significant [2, 32, 34]. Fehrmann (2011) suggests that ‘the search process being described in detail’ and that, where standard comprehensive search techniques have been applied, increases confidence in the search results [32].

Does comprehensive literature searching work?

Egger et al., and other study authors, have demonstrated a change in the estimate of intervention effectiveness where relevant studies were excluded from meta-analysis [34, 47]. This would suggest that missing studies in literature searching alters the reliability of effectiveness estimates. This is an argument for comprehensive literature searching. Conversely, Egger et al. found that ‘comprehensive’ searches still missed studies and that comprehensive searches could, in fact, introduce bias into a review rather than preventing it, through the identification of low quality studies then being included in the meta-analysis [34]. Studies query if identifying and including low quality or grey literature studies changes the estimate of effect [43, 48] and question if time is better invested updating systematic reviews rather than searching for unpublished studies [49], or mapping studies for review as opposed to aiming for high sensitivity in literature searching [50].

Aim and purpose beyond reviews of effectiveness

The need for comprehensive literature searches is less certain in reviews of qualitative studies, and for reviews where a comprehensive identification of studies is difficult to achieve (for example, in Public health) [33, 51,52,53,54,55]. Literature searching for qualitative studies, and in public health topics, typically generates a greater number of studies to sift than in reviews of effectiveness [39] and demonstrating the ‘value’ of studies identified or missed is harder [56], since the study data do not typically support meta-analysis. Nussbaumer-Streit et al. (2016) have registered a review protocol to assess whether abbreviated literature searches (as opposed to comprehensive literature searches) has an impact on conclusions across multiple bodies of evidence, not only on effect estimates [57] which may develop this understanding. It may be that decision makers and users of systematic reviews are willing to trade the certainty from a comprehensive literature search and systematic review in exchange for different approaches to evidence synthesis [58], and that comprehensive literature searches are not necessarily a marker of literature search quality, as previously thought [36]. Different approaches to literature searching [37, 38, 59,60,61,62] and developing the concept of when to stop searching are important areas for further study [36, 59].

The study by Nussbaumer-Streit et al. has been published since the submission of this literature review [63]. Nussbaumer-Streit et al. (2018) conclude that abbreviated literature searches are viable options for rapid evidence syntheses, if decision-makers are willing to trade the certainty from a comprehensive literature search and systematic review, but that decision-making which demands detailed scrutiny should still be based on comprehensive literature searches [63].

Key stage three: Preparing for the literature search

The guidance

Six documents provided guidance on preparing for a literature search [2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10]. The Cochrane Handbook clearly stated that Cochrane authors (i.e. researchers) should seek advice from a trial search co-ordinator (i.e. a person with specific skills in literature searching) ‘before’ starting a literature search [9].

Two key tasks were perceptible in preparing for a literature searching [2, 6, 7, 10, 11]. First, to determine if there are any existing or on-going reviews, or if a new review is justified [6, 11]; and, secondly, to develop an initial literature search strategy to estimate the volume of relevant literature (and quality of a small sample of relevant studies [10]) and indicate the resources required for literature searching and the review of the studies that follows [7, 10].

Three documents summarised guidance on where to search to determine if a new review was justified [2, 6, 11]. These focused on searching databases of systematic reviews (The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)), institutional registries (including PROSPERO), and MEDLINE [6, 11]. It is worth noting, however, that as of 2015, DARE (and NHS EEDs) are no longer being updated and so the relevance of this (these) resource(s) will diminish over-time [64]. One guidance document, ‘Systematic reviews in the Social Sciences’, noted, however, that databases are not the only source of information and unpublished reports, conference proceeding and grey literature may also be required, depending on the nature of the review question [2].

Two documents reported clearly that this preparation (or ‘scoping’) exercise should be undertaken before the actual search strategy is developed [7, 10]).

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

The guidance offers the best available source on preparing the literature search with the published studies not typically reporting how their scoping informed the development of their search strategies nor how their search approaches were developed. Text mining has been proposed as a technique to develop search strategies in the scoping stages of a review although this work is still exploratory [65]. ‘Clustering documents’ and word frequency analysis have also been tested to identify search terms and studies for review [66, 67]. Preparing for literature searches and scoping constitutes an area for future research.

Key stage four: Designing the search strategy

The guidance

The Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) structure was the commonly reported structure promoted to design a literature search strategy. Five documents suggested that the eligibility criteria or review question will determine which concepts of PICO will be populated to develop the search strategy [1, 4, 7,8,9]. The NICE handbook promoted multiple structures, namely PICO, SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation) and multi-stranded approaches [4].

With the exclusion of The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual, the guidance offered detail on selecting key search terms, synonyms, Boolean language, selecting database indexing terms and combining search terms. The CEE handbook suggested that ‘search terms may be compiled with the help of the commissioning organisation and stakeholders’ [10].

The use of limits, such as language or date limits, were discussed in all documents [2,3,4, 6,7,8,9,10,11].

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

Search strategy structure

The guidance typically relates to reviews of intervention effectiveness so PICO – with its focus on intervention and comparator - is the dominant model used to structure literature search strategies [68]. PICOs – where the S denotes study design - is also commonly used in effectiveness reviews [6, 68]. As the NICE handbook notes, alternative models to structure literature search strategies have been developed and tested. Booth provides an overview on formulating questions for evidence based practice [69] and has developed a number of alternatives to the PICO structure, namely: BeHEMoTh (Behaviour of interest; Health context; Exclusions; Models or Theories) for use when systematically identifying theory [55]; SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation) for identification of social science and evaluation studies [69] and, working with Cooke and colleagues, SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) [70]. SPIDER has been compared to PICO and PICOs in a study by Methley et al. [68].

The NICE handbook also suggests the use of multi-stranded approaches to developing literature search strategies [4]. Glanville developed this idea in a study by Whitting et al. [71] and a worked example of this approach is included in the development of a search filter by Cooper et al. [72].

Writing search strategies: Conceptual and objective approaches

Hausner et al. [73] provide guidance on writing literature search strategies, delineating between conceptually and objectively derived approaches. The conceptual approach, advocated by and explained in the guidance documents, relies on the expertise of the literature searcher to identify key search terms and then develop key terms to include synonyms and controlled syntax. Hausner and colleagues set out the objective approach [73] and describe what may be done to validate it [74].

The use of limits

The guidance documents offer direction on the use of limits within a literature search. Limits can be used to focus literature searching to specific study designs or by other markers (such as by date) which limits the number of studies returned by a literature search. The use of limits should be described and the implications explored [34] since limiting literature searching can introduce bias (explored above). Craven et al. have suggested the use of a supporting narrative to explain decisions made in the process of developing literature searches and this advice would usefully capture decisions on the use of search limits [75].

Key stage five: Determining the process of literature searching and deciding where to search (bibliographic database searching)

The guidance

Table 2 summarises the process of literature searching as reported in each guidance document. Searching bibliographic databases was consistently reported as the ‘first step’ to literature searching in all nine guidance documents.

Three documents reported specific guidance on where to search, in each case specific to the type of review their guidance informed, and as a minimum requirement [4, 9, 11]. Seven of the key guidance documents suggest that the selection of bibliographic databases depends on the topic of review [2,3,4, 6,7,8, 10], with two documents noting the absence of an agreed standard on what constitutes an acceptable number of databases searched [2, 6].

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

The guidance documents summarise ‘how to’ search bibliographic databases in detail and this guidance is further contextualised above in terms of developing the search strategy. The documents provide guidance of selecting bibliographic databases, in some cases stating acceptable minima (i.e. The Cochrane Handbook states Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE), and in other cases simply listing bibliographic database available to search. Studies have explored the value in searching specific bibliographic databases, with Wright et al. (2015) noting the contribution of CINAHL in identifying qualitative studies [76], Beckles et al. (2013) questioning the contribution of CINAHL to identifying clinical studies for guideline development [77], and Cooper et al. (2015) exploring the role of UK-focused bibliographic databases to identify UK-relevant studies [78]. The host of the database (e.g. OVID or ProQuest) has been shown to alter the search returns offered. Younger and Boddy [79] report differing search returns from the same database (AMED) but where the ‘host’ was different [79].

The average number of bibliographic database searched in systematic reviews has risen in the period 1994–2014 (from 1 to 4) [80] but there remains (as attested to by the guidance) no consensus on what constitutes an acceptable number of databases searched [48]. This is perhaps because thinking about the number of databases searched is the wrong question, researchers should be focused on which databases were searched and why, and which databases were not searched and why. The discussion should re-orientate to the differential value of sources but researchers need to think about how to report this in studies to allow findings to be generalised. Bethel (2017) has proposed ‘search summaries’, completed by the literature searcher, to record where included studies were identified, whether from database (and which databases specifically) or supplementary search methods [81]. Search summaries document both yield and accuracy of searches, which could prospectively inform resource use and decisions to search or not to search specific databases in topic areas. The prospective use of such data presupposes, however, that past searches are a potential predictor of future search performance (i.e. that each topic is to be considered representative and not unique). In offering a body of practice, this data would be of greater practicable use than current studies which are considered as little more than individual case studies [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

When to database search is another question posed in the literature. Beyer et al. [91] report that databases can be prioritised for literature searching which, whilst not addressing the question of which databases to search, may at least bring clarity as to which databases to search first [91]. Paradoxically, this links to studies that suggest PubMed should be searched in addition to MEDLINE (OVID interface) since this improves the currency of systematic reviews [92, 93]. Cooper et al. (2017) have tested the idea of database searching not as a primary search method (as suggested in the guidance) but as a supplementary search method in order to manage the volume of studies identified for an environmental effectiveness systematic review. Their case study compared the effectiveness of database searching versus a protocol using supplementary search methods and found that the latter identified more relevant studies for review than searching bibliographic databases [94].

Key stage six: Determining the process of literature searching and deciding where to search (supplementary search methods)

The guidance

Table 2 also summaries the process of literature searching which follows bibliographic database searching. As Table 2 sets out, guidance that supplementary literature search methods should be used in systematic reviews recurs across documents, but the order in which these methods are used, and the extent to which they are used, varies. We noted inconsistency in the labelling of supplementary search methods between guidance documents.

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

Rather than focus on the guidance on how to use the methods (which has been summarised in a recent review [95]), we focus on the aim or purpose of supplementary search methods.

The Cochrane Handbook reported that ‘efforts’ to identify unpublished studies should be made [9]. Four guidance documents [2, 3, 6, 9] acknowledged that searching beyond bibliographic databases was necessary since ‘databases are not the only source of literature’ [2]. Only one document reported any guidance on determining when to use supplementary methods. The IQWiG handbook reported that the use of handsearching (in their example) could be determined on a ‘case-by-case basis’ which implies that the use of these methods is optional rather than mandatory. This is in contrast to the guidance (above) on bibliographic database searching.

The issue for supplementary search methods is similar in many ways to the issue of searching bibliographic databases: demonstrating value. The purpose and contribution of supplementary search methods in systematic reviews is increasingly acknowledged [37, 61, 62, 96,97,98,99,100,101] but understanding the value of the search methods to identify studies and data is unclear. In a recently published review, Cooper et al. (2017) reviewed the literature on supplementary search methods looking to determine the advantages, disadvantages and resource implications of using supplementary search methods [95]. This review also summarises the key guidance and empirical studies and seeks to address the question on when to use these search methods and when not to [95]. The guidance is limited in this regard and, as Table 2 demonstrates, offers conflicting advice on the order of searching, and the extent to which these search methods should be used in systematic reviews.

Key stage seven: Managing the references

The guidance

Five of the documents provided guidance on managing references, for example downloading, de-duplicating and managing the output of literature searches [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]. This guidance typically itemised available bibliographic management tools rather than offering guidance on how to use them specifically [2, 4, 6, 8]. The CEE handbook provided guidance on importing data where no direct export option is available (e.g. web-searching) [10].

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

The literature on using bibliographic management tools is not large relative to the number of ‘how to’ videos on platforms such as YouTube (see for example [102]). These YouTube videos confirm the overall lack of ‘how to’ guidance identified in this study and offer useful instruction on managing references. Bramer et al. set out methods for de-duplicating data and reviewing references in Endnote [103, 104] and Gall tests the direct search function within Endnote to access databases such as PubMed, finding a number of limitations [105]. Coar et al. and Ahmed et al. consider the role of the free-source tool, Zotero [106, 107]. Managing references is a key administrative function in the process of review particularly for documenting searches in PRISMA guidance.

Key stage eight: Documenting the search

The guidance

The Cochrane Handbook was the only guidance document to recommend a specific reporting guideline: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [9]. Six documents provided guidance on reporting the process of literature searching with specific criteria to report [3, 4, 6, 8,9,10]. There was consensus on reporting: the databases searched (and the host searched by), the search strategies used, and any use of limits (e.g. date, language, search filters (The CRD handbook called for these limits to be justified [6])). Three guidance documents reported that the number of studies identified should be recorded [3, 6, 10]. The number of duplicates identified [10], the screening decisions [3], a comprehensive list of grey literature sources searched (and full detail for other supplementary search methods) [8], and an annotation of search terms tested but not used [4] were identified as unique items in four documents.

The Cochrane Handbook was the only guidance document to note that the full search strategies for each database should be included in the Additional file 1 of the review [9].

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

All guidance documents should ultimately deliver completed systematic reviews that fulfil the requirements of the PRISMA reporting guidelines [108]. The guidance broadly requires the reporting of data that corresponds with the requirements of the PRISMA statement although documents typically ask for diverse and additional items [108]. In 2008, Sampson et al. observed a lack of consensus on reporting search methods in systematic reviews [109] and this remains the case as of 2017, as evidenced in the guidance documents, and in spite of the publication of the PRISMA guidelines in 2009 [110]. It is unclear why the collective guidance does not more explicitly endorse adherence to the PRISMA guidance.

Reporting of literature searching is a key area in systematic reviews since it sets out clearly what was done and how the conclusions of the review can be believed [52, 109]. Despite strong endorsement in the guidance documents, specifically supported in PRISMA guidance, and other related reporting standards too (such as ENTREQ for qualitative evidence synthesis, STROBE for reviews of observational studies), authors still highlight the prevalence of poor standards of literature search reporting [31, 110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119]. To explore issues experienced by authors in reporting literature searches, and look at uptake of PRISMA, Radar et al. [120] surveyed over 260 review authors to determine common problems and their work summaries the practical aspects of reporting literature searching [120]. Atkinson et al. [121] have also analysed reporting standards for literature searching, summarising recommendations and gaps for reporting search strategies [121].

One area that is less well covered by the guidance, but nevertheless appears in this literature, is the quality appraisal or peer review of literature search strategies. The PRESS checklist is the most prominent and it aims to develop evidence-based guidelines to peer review of electronic search strategies [5, 122, 123]. A corresponding guideline for documentation of supplementary search methods does not yet exist although this idea is currently being explored.

How the reporting of the literature searching process corresponds to critical appraisal tools is an area for further research. In the survey undertaken by Radar et al. (2014), 86% of survey respondents (153/178) identified a need for further guidance on what aspects of the literature search process to report [120]. The PRISMA statement offers a brief summary of what to report but little practical guidance on how to report it [108]. Critical appraisal tools for systematic reviews, such as AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al. [124]) and ROBIS (Whiting et al. [125]), can usefully be read alongside PRISMA guidance, since they offer greater detail on how the reporting of the literature search will be appraised and, therefore, they offer a proxy on what to report [124, 125]. Further research in the form of a study which undertakes a comparison between PRISMA and quality appraisal checklists for systematic reviews would seem to begin addressing the call, identified by Radar et al., for further guidance on what to report [120].

Limitations

Other handbooks exist

A potential limitation of this literature review is the focus on guidance produced in Europe (the UK specifically) and Australia. We justify the decision for our selection of the nine guidance documents reviewed in this literature review in section “Identifying guidance”. In brief, these nine guidance documents were selected as the most relevant health care guidance that inform UK systematic reviewing practice, given that the UK occupies a prominent position in the science of health information retrieval. We acknowledge the existence of other guidance documents, such as those from North America (e.g. the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [126], The Institute of Medicine [127] and the guidance and resources produced by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) [128]). We comment further on this directly below.

The handbooks are potentially linked to one another

What is not clear is the extent to which the guidance documents inter-relate or provide guidance uniquely. The Cochrane Handbook, first published in 1994, is notably a key source of reference in guidance and systematic reviews beyond Cochrane reviews. It is not clear to what extent broadening the sample of guidance handbooks to include North American handbooks, and guidance handbooks from other relevant countries too, would alter the findings of this literature review or develop further support for the process model. Since we cannot be clear, we raise this as a potential limitation of this literature review. On our initial review of a sample of North American, and other, guidance documents (before selecting the guidance documents considered in this review), however, we do not consider that the inclusion of these further handbooks would alter significantly the findings of this literature review.

This is a literature review

A further limitation of this review was that the review of published studies is not a systematic review of the evidence for each key stage. It is possible that other relevant studies could help contribute to the exploration and development of the key stages identified in this review.

Conclusions

This literature review would appear to demonstrate the existence of a shared model of the literature searching process in systematic reviews. We call this model ‘the conventional approach’, since it appears to be common convention in nine different guidance documents.

The findings reported above reveal eight key stages in the process of literature searching for systematic reviews. These key stages are consistently reported in the nine guidance documents which suggests consensus on the key stages of literature searching, and therefore the process of literature searching as a whole, in systematic reviews.

In Table 2, we demonstrate consensus regarding the application of literature search methods. All guidance documents distinguish between primary and supplementary search methods. Bibliographic database searching is consistently the first method of literature searching referenced in each guidance document. Whilst the guidance uniformly supports the use of supplementary search methods, there is little evidence for a consistent process with diverse guidance across documents. This may reflect differences in the core focus across each document, linked to differences in identifying effectiveness studies or qualitative studies, for instance.

Eight of the nine guidance documents reported on the aims of literature searching. The shared understanding was that literature searching should be thorough and comprehensive in its aim and that this process should be reported transparently so that that it could be reproduced. Whilst only three documents explicitly link this understanding to minimising bias, it is clear that comprehensive literature searching is implicitly linked to ‘not missing relevant studies’ which is approximately the same point.

Defining the key stages in this review helps categorise the scholarship available, and it prioritises areas for development or further study. The supporting studies on preparing for literature searching (key stage three, ‘preparation’) were, for example, comparatively few, and yet this key stage represents a decisive moment in literature searching for systematic reviews. It is where search strategy structure is determined, search terms are chosen or discarded, and the resources to be searched are selected. Information specialists, librarians and researchers, are well placed to develop these and other areas within the key stages we identify.

This review calls for further research to determine the suitability of using the conventional approach. The publication dates of the guidance documents which underpin the conventional approach may raise questions as to whether the process which they each report remains valid for current systematic literature searching. In addition, it may be useful to test whether it is desirable to use the same process model of literature searching for qualitative evidence synthesis as that for reviews of intervention effectiveness, which this literature review demonstrates is presently recommended best practice.

Abbreviations

- BeHEMoTh:

-

Behaviour of interest; Health context; Exclusions; Models or Theories

- CDSR:

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Cochrane CENTRAL:

-

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- DARE:

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

- ENTREQ:

-

Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research

- IQWiG:

-

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Clinical Excellence

- PICO:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SPICE:

-

Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation

- SPIDER:

-

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- TSC:

-

Trial Search Co-ordinators

References

Booth A. Unpacking your literature search toolbox: on search styles and tactics. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2008;25(4):313–7.

Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006.

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). IQWiG Methods Resources. 7 Information retrieval 2014 [Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK385787/.

NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/media/default/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/developing-nice-guidelines-the-manual.pdf.

Sampson M. MJ, Lefebvre C, Moher D, Grimshaw J. Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: PRESS; 2008.

Centre for Reviews & Dissemination. Systematic reviews – CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2009.

eunetha: European Network for Health Technology Assesment Process of information retrieval for systematic reviews and health technology assessments on clinical effectiveness 2016. Available from: http://www.eunethta.eu/sites/default/files/Guideline_Information_Retrieval_V1-1.pdf.

Kugley SWA, Thomas J, Mahood Q, Jørgensen AMK, Hammerstrøm K, Sathe N. Searching for studies: a guide to information retrieval for Campbell systematic reviews. Oslo: Campbell Collaboration. 2017; Available from: https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/library/searching-for-studies-information-retrieval-guide-campbell-reviews.html

Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: searching for studies. In: JPT H, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; 2011.

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. Guidelines for Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis in Environmental Management.: Environmental Evidence:; 2013. Available from: http://www.environmentalevidence.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Review-guidelines-version-4.2-final-update.pdf.

The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual. 2014th ed: the Joanna Briggs institute; 2014. Available from: https://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual-2014.pdf

Beverley CA, Booth A, Bath PA. The role of the information specialist in the systematic review process: a health information case study. Health Inf Libr J. 2003;20(2):65–74.

Harris MR. The librarian's roles in the systematic review process: a case study. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2005;93(1):81–7.

Egger JB. Use of recommended search strategies in systematic reviews and the impact of librarian involvement: a cross-sectional survey of recent authors. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125931.

Li L, Tian J, Tian H, Moher D, Liang F, Jiang T, et al. Network meta-analyses could be improved by searching more sources and by involving a librarian. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(9):1001–7.

McGowan J, Sampson M. Systematic reviews need systematic searchers. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93(1):74–80.

Rethlefsen ML, Farrell AM, Osterhaus Trzasko LC, Brigham TJ. Librarian co-authors correlated with higher quality reported search strategies in general internal medicine systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(6):617–26.

Weller AC. Mounting evidence that librarians are essential for comprehensive literature searches for meta-analyses and Cochrane reports. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004;92(2):163–4.

Swinkels A, Briddon J, Hall J. Two physiotherapists, one librarian and a systematic literature review: collaboration in action. Health Info Libr J. 2006;23(4):248–56.

Foster M. An overview of the role of librarians in systematic reviews: from expert search to project manager. EAHIL. 2015;11(3):3–7.

Lawson L. OPERATING OUTSIDE LIBRARY WALLS 2004.

Vassar M, Yerokhin V, Sinnett PM, Weiher M, Muckelrath H, Carr B, et al. Database selection in systematic reviews: an insight through clinical neurology. Health Inf Libr J. 2017;34(2):156–64.

Townsend WA, Anderson PF, Ginier EC, MacEachern MP, Saylor KM, Shipman BL, et al. A competency framework for librarians involved in systematic reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2017;105(3):268–75.

Cooper ID, Crum JA. New activities and changing roles of health sciences librarians: a systematic review, 1990-2012. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2013;101(4):268–77.

Crum JA, Cooper ID. Emerging roles for biomedical librarians: a survey of current practice, challenges, and changes. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2013;101(4):278–86.

Dudden RF, Protzko SL. The systematic review team: contributions of the health sciences librarian. Med Ref Serv Q. 2011;30(3):301–15.

Golder S, Loke Y, McIntosh HM. Poor reporting and inadequate searches were apparent in systematic reviews of adverse effects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):440–8.

Maggio LA, Tannery NH, Kanter SL. Reproducibility of literature search reporting in medical education reviews. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2011;86(8):1049–54.

Meert D, Torabi N, Costella J. Impact of librarians on reporting of the literature searching component of pediatric systematic reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2016;104(4):267–77.

Morris M, Boruff JT, Gore GC. Scoping reviews: establishing the role of the librarian. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2016;104(4):346–54.

Koffel JB, Rethlefsen ML. Reproducibility of search strategies is poor in systematic reviews published in high-impact pediatrics, cardiology and surgery journals: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163309.

Fehrmann P, Thomas J. Comprehensive computer searches and reporting in systematic reviews. Research Synthesis Methods. 2011;2(1):15–32.

Booth A. Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):74.

Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, Holenstein F, Sterne J. How important are comprehensive literature searches and the assessment of trial quality in systematic reviews? Empirical study. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2003;7(1):1–76.

Tricco AC, Tetzlaff J, Sampson M, Fergusson D, Cogo E, Horsley T, et al. Few systematic reviews exist documenting the extent of bias: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):422–34.

Booth A. How much searching is enough? Comprehensive versus optimal retrieval for technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2010;26(4):431–5.

Papaioannou D, Sutton A, Carroll C, Booth A, Wong R. Literature searching for social science systematic reviews: consideration of a range of search techniques. Health Inf Libr J. 2010;27(2):114–22.

Petticrew M. Time to rethink the systematic review catechism? Moving from ‘what works’ to ‘what happens’. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):36.

Betrán AP, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Allen T, Hampson L. Effectiveness of different databases in identifying studies for systematic reviews: experience from the WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5

Felson DT. Bias in meta-analytic research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(8):885–92.

Franco A, Malhotra N, Simonovits G. Publication bias in the social sciences: unlocking the file drawer. Science. 2014;345(6203):1502–5.

Hartling L, Featherstone R, Nuspl M, Shave K, Dryden DM, Vandermeer B. Grey literature in systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-English reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):64.

Schmucker CM, Blümle A, Schell LK, Schwarzer G, Oeller P, Cabrera L, et al. Systematic review finds that study data not published in full text articles have unclear impact on meta-analyses results in medical research. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0176210.

Egger M, Zellweger-Zahner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet (London, England). 1997;350(9074):326–9.

Moher D, Pham B, Lawson ML, Klassen TP. The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2003;7(41):1–90.

Pham B, Klassen TP, Lawson ML, Moher D. Language of publication restrictions in systematic reviews gave different results depending on whether the intervention was conventional or complementary. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(8):769–76.

Mills EJ, Kanters S, Thorlund K, Chaimani A, Veroniki A-A, Ioannidis JPA. The effects of excluding treatments from network meta-analyses: survey. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2013;347

Hartling L, Featherstone R, Nuspl M, Shave K, Dryden DM, Vandermeer B. The contribution of databases to the results of systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):127.

van Driel ML, De Sutter A, De Maeseneer J, Christiaens T. Searching for unpublished trials in Cochrane reviews may not be worth the effort. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(8):838–44.e3.

Buchberger B, Krabbe L, Lux B, Mattivi JT. Evidence mapping for decision making: feasibility versus accuracy - when to abandon high sensitivity in electronic searches. German medical science : GMS e-journal. 2016;14:Doc09.

Lorenc T, Pearson M, Jamal F, Cooper C, Garside R. The role of systematic reviews of qualitative evidence in evaluating interventions: a case study. Research Synthesis Methods. 2012;3(1):1–10.

Gough D. Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Res Pap Educ. 2007;22(2):213–28.

Barroso J, Gollop CJ, Sandelowski M, Meynell J, Pearce PF, Collins LJ. The challenges of searching for and retrieving qualitative studies. West J Nurs Res. 2003;25(2):153–78.

Britten N, Garside R, Pope C, Frost J, Cooper C. Asking more of qualitative synthesis: a response to Sally Thorne. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(9):1370–6.

Booth A, Carroll C. Systematic searching for theory to inform systematic reviews: is it feasible? Is it desirable? Health Info Libr J. 2015;32(3):220–35.

Kwon Y, Powelson SE, Wong H, Ghali WA, Conly JM. An assessment of the efficacy of searching in biomedical databases beyond MEDLINE in identifying studies for a systematic review on ward closures as an infection control intervention to control outbreaks. Syst Rev. 2014;3:135.

Nussbaumer-Streit B, Klerings I, Wagner G, Titscher V, Gartlehner G. Assessing the validity of abbreviated literature searches for rapid reviews: protocol of a non-inferiority and meta-epidemiologic study. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5:197.

Wagner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Greimel J, Ciapponi A, Gartlehner G. Trading certainty for speed - how much uncertainty are decisionmakers and guideline developers willing to accept when using rapid reviews: an international survey. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):121.

Ogilvie D, Hamilton V, Egan M, Petticrew M. Systematic reviews of health effects of social interventions: 1. Finding the evidence: how far should you go? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(9):804–8.

Royle P, Milne R. Literature searching for randomized controlled trials used in Cochrane reviews: rapid versus exhaustive searches. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(4):591–603.

Pearson M, Moxham T, Ashton K. Effectiveness of search strategies for qualitative research about barriers and facilitators of program delivery. Eval Health Prof. 2011;34(3):297–308.

Levay P, Raynor M, Tuvey D. The Contributions of MEDLINE, Other Bibliographic Databases and Various Search Techniques to NICE Public Health Guidance. 2015. 2015;10(1):19.

Nussbaumer-Streit B, Klerings I, Wagner G, Heise TL, Dobrescu AI, Armijo-Olivo S, et al. Abbreviated literature searches were viable alternatives to comprehensive searches: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;102:1–11.

Briscoe S, Cooper C, Glanville J, Lefebvre C. The loss of the NHS EED and DARE databases and the effect on evidence synthesis and evaluation. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8(3):256–7.

Stansfield C, O'Mara-Eves A, Thomas J. Text mining for search term development in systematic reviewing: A discussion of some methods and challenges. Research Synthesis Methods.n/a-n/a.

Petrova M, Sutcliffe P, Fulford KW, Dale J. Search terms and a validated brief search filter to retrieve publications on health-related values in Medline: a word frequency analysis study. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2012;19(3):479–88.

Stansfield C, Thomas J, Kavanagh J. 'Clustering' documents automatically to support scoping reviews of research: a case study. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4(3):230–41.

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579.

Andrew B. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech. 2006;24(3):355–68.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Whiting P, Westwood M, Bojke L, Palmer S, Richardson G, Cooper J, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of tests for the diagnosis and investigation of urinary tract infection in children: a systematic review and economic model. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2006;10(36):iii-iv, xi-xiii, 1–154.

Cooper C, Levay P, Lorenc T, Craig GM. A population search filter for hard-to-reach populations increased search efficiency for a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(5):554–9.

Hausner E, Waffenschmidt S, Kaiser T, Simon M. Routine development of objectively derived search strategies. Systematic Reviews. 2012;1(1):19.

Hausner E, Guddat C, Hermanns T, Lampert U, Waffenschmidt S. Prospective comparison of search strategies for systematic reviews: an objective approach yielded higher sensitivity than a conceptual one. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;77:118–24.

Craven J, Levay P. Recording database searches for systematic reviews - what is the value of adding a narrative to peer-review checklists? A case study of nice interventional procedures guidance. Evid Based Libr Inf Pract. 2011;6(4):72–87.

Wright K, Golder S, Lewis-Light K. What value is the CINAHL database when searching for systematic reviews of qualitative studies? Syst Rev. 2015;4:104.

Beckles Z, Glover S, Ashe J, Stockton S, Boynton J, Lai R, et al. Searching CINAHL did not add value to clinical questions posed in NICE guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(9):1051–7.

Cooper C, Rogers M, Bethel A, Briscoe S, Lowe J. A mapping review of the literature on UK-focused health and social care databases. Health Inf Libr J. 2015;32(1):5–22.

Younger P, Boddy K. When is a search not a search? A comparison of searching the AMED complementary health database via EBSCOhost, OVID and DIALOG. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):126–35.

Lam MT, McDiarmid M. Increasing number of databases searched in systematic reviews and meta-analyses between 1994 and 2014. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2016;104(4):284–9.

Bethel A, editor Search summary tables for systematic reviews: results and findings. HLC Conference 2017a.

Aagaard T, Lund H, Juhl C. Optimizing literature search in systematic reviews - are MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL enough for identifying effect studies within the area of musculoskeletal disorders? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):161.

Adams CE, Frederick K. An investigation of the adequacy of MEDLINE searches for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of the effects of mental health care. Psychol Med. 1994;24(3):741–8.

Kelly L, St Pierre-Hansen N. So many databases, such little clarity: searching the literature for the topic aboriginal. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2008;54(11):1572–3.

Lawrence DW. What is lost when searching only one literature database for articles relevant to injury prevention and safety promotion? Injury Prevention. 2008;14(6):401–4.

Lemeshow AR, Blum RE, Berlin JA, Stoto MA, Colditz GA. Searching one or two databases was insufficient for meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(9):867–73.

Sampson M, Barrowman NJ, Moher D, Klassen TP, Pham B, Platt R, et al. Should meta-analysts search Embase in addition to Medline? J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(10):943–55.

Stevinson C, Lawlor DA. Searching multiple databases for systematic reviews: added value or diminishing returns? Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2004;12(4):228–32.

Suarez-Almazor ME, Belseck E, Homik J, Dorgan M, Ramos-Remus C. Identifying clinical trials in the medical literature with electronic databases: MEDLINE alone is not enough. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21(5):476–87.

Taylor B, Wylie E, Dempster M, Donnelly M. Systematically retrieving research: a case study evaluating seven databases. Res Soc Work Pract. 2007;17(6):697–706.

Beyer FR, Wright K. Can we prioritise which databases to search? A case study using a systematic review of frozen shoulder management. Health Info Libr J. 2013;30(1):49–58.

Duffy S, de Kock S, Misso K, Noake C, Ross J, Stirk L. Supplementary searches of PubMed to improve currency of MEDLINE and MEDLINE in-process searches via Ovid. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2016;104(4):309–12.

Katchamart W, Faulkner A, Feldman B, Tomlinson G, Bombardier C. PubMed had a higher sensitivity than Ovid-MEDLINE in the search for systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):805–7.

Cooper C, Lovell R, Husk K, Booth A, Garside R. Supplementary search methods were more effective and offered better value than bibliographic database searching: a case study from public health and environmental enhancement (in Press). Research Synthesis Methods. 2017;

Cooper C, Booth, A., Britten, N., Garside, R. A comparison of results of empirical studies of supplementary search techniques and recommendations in review methodology handbooks: A methodological review. (In Press). BMC Systematic Reviews. 2017.

Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2005;331(7524):1064–5.

Hinde S, Spackman E. Bidirectional citation searching to completion: an exploration of literature searching methods. PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(1):5–11.

Levay P, Ainsworth N, Kettle R, Morgan A. Identifying evidence for public health guidance: a comparison of citation searching with web of science and Google scholar. Res Synth Methods. 2016;7(1):34–45.

McManus RJ, Wilson S, Delaney BC, Fitzmaurice DA, Hyde CJ, Tobias RS, et al. Review of the usefulness of contacting other experts when conducting a literature search for systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1998;317(7172):1562–3.

Westphal A, Kriston L, Holzel LP, Harter M, von Wolff A. Efficiency and contribution of strategies for finding randomized controlled trials: a case study from a systematic review on therapeutic interventions of chronic depression. Journal of public health research. 2014;3(2):177.

Matthews EJ, Edwards AG, Barker J, Bloor M, Covey J, Hood K, et al. Efficient literature searching in diffuse topics: lessons from a systematic review of research on communicating risk to patients in primary care. Health Libr Rev. 1999;16(2):112–20.

Bethel A. Endnote Training (YouTube Videos) 2017b [Available from: http://medicine.exeter.ac.uk/esmi/workstreams/informationscience/is_resources,_guidance_&_advice/.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2016;104(3):240–3.

Bramer WM, Milic J, Mast F. Reviewing retrieved references for inclusion in systematic reviews using EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2017;105(1):84–7.

Gall C, Brahmi FA. Retrieval comparison of EndNote to search MEDLINE (Ovid and PubMed) versus searching them directly. Medical reference services quarterly. 2004;23(3):25–32.

Ahmed KK, Al Dhubaib BE. Zotero: a bibliographic assistant to researcher. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2(4):303–5.

Coar JT, Sewell JP. Zotero: harnessing the power of a personal bibliographic manager. Nurse Educ. 2010;35(5):205–7.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Sampson M, McGowan J, Tetzlaff J, Cogo E, Moher D. No consensus exists on search reporting methods for systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(8):748–54.

Toews LC. Compliance of systematic reviews in veterinary journals with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) literature search reporting guidelines. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2017;105(3):233–9.

Booth A. "brimful of STARLITE": toward standards for reporting literature searches. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2006;94(4):421–9. e205

Faggion CM Jr, Wu YC, Tu YK, Wasiak J. Quality of search strategies reported in systematic reviews published in stereotactic radiosurgery. Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1062):20150878.

Mullins MM, DeLuca JB, Crepaz N, Lyles CM. Reporting quality of search methods in systematic reviews of HIV behavioral interventions (2000–2010): are the searches clearly explained, systematic and reproducible? Research Synthesis Methods. 2014;5(2):116–30.

Yoshii A, Plaut DA, McGraw KA, Anderson MJ, Wellik KE. Analysis of the reporting of search strategies in Cochrane systematic reviews. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA. 2009;97(1):21–9.

Bigna JJ, Um LN, Nansseu JR. A comparison of quality of abstracts of systematic reviews including meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in high-impact general medicine journals before and after the publication of PRISMA extension for abstracts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):174.

Akhigbe T, Zolnourian A, Bulters D. Compliance of systematic reviews articles in brain arteriovenous malformation with PRISMA statement guidelines: review of literature. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2017;39:45–8.

Tao KM, Li XQ, Zhou QH, Moher D, Ling CQ, Yu WF. From QUOROM to PRISMA: a survey of high-impact medical journals' instructions to authors and a review of systematic reviews in anesthesia literature. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27611.

Wasiak J, Tyack Z, Ware R. Goodwin N. Jr. Poor methodological quality and reporting standards of systematic reviews in burn care management. International wound journal: Faggion CM; 2016.

Tam WW, Lo KK, Khalechelvam P. Endorsement of PRISMA statement and quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in nursing journals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e013905.

Rader T, Mann M, Stansfield C, Cooper C, Sampson M. Methods for documenting systematic review searches: a discussion of common issues. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(2):98–115.

Atkinson KM, Koenka AC, Sanchez CE, Moshontz H, Cooper H. Reporting standards for literature searches and report inclusion criteria: making research syntheses more transparent and easy to replicate. Res Synth Methods. 2015;6(1):87–95.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(9):944–52.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358.

Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JPT, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, et al. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–34.

Relevo R, Balshem H. Finding evidence for comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the effective health care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1168–77.

Medicine Io. Standards for Systematic Reviews 2011 [Available from: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Finding-What-Works-in-Health-Care-Standards-for-Systematic-Reviews/Standards.aspx.

CADTH: Resources 2018.

Acknowledgements

CC acknowledges the supervision offered by Professor Chris Hyde.

Funding

This publication forms a part of CC’s PhD. CC’s PhD was funded through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme (Project Number 16/54/11). The open access fee for this publication was paid for by Exeter Medical School.

RG and NB were partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC conceived the idea for this study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CC discussed this publication in PhD supervision with AB and separately with JVC. CC revised the publication with input and comments from AB, JVC, RG and NB. All authors revised the manuscript prior to submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Appendix tables and PubMed search strategy. Key studies used for pearl growing per key stage, working data extraction tables and the PubMed search strategy. (DOCX 30 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, C., Booth, A., Varley-Campbell, J. et al. Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 18, 85 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0545-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0545-3