Abstract

Background

Patients with Turner syndrome (TS) are prone to autoimmune disorders. Although most patients with TS are diagnosed at younger ages, delayed diagnosis is not rare.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old woman was presented with facial edema, chest tightness and dyspnea. She had primary amenorrhea. Physical examination revealed short stature, dry skin and coarse hair. Periorbital edema with puffy eyelids were also noticed with mild goiter. Bilateral cardiac enlargement, distant heart sounds and pulsus paradoxus, in combination with hepatomegaly and jugular venous distention were observed. Her hircus and pubic hair was absent. The development of her breast was at 1st tanner period and gynecological examination revealed infantile vulva. Echocardiography suggested massive pericardial effusion. She was diagnosed with cardiac tamponade based on low systolic pressure, decreased pulse pressure and pulsus paradoxus. Pericardiocentesis was performed. Thyroid function test and thyroid ultrasound indicated Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and severe hypothyroidism. Sex hormone test revealed hypergonadotropin hypogonadism. Further karyotyping revealed a karyotype of 45, X [21]/46, X, i(X) (q10) [29] and she was diagnosed with mosaic + variant type of TS. L-T4 supplement, estrogen therapy, and antiosteoporosis treatment was initiated. Euthyroidism and complete resolution of the pericardial effusion was obtained within 2 months.

Conclusion

Hypothyroidism should be considered in the patients with pericardial effusion. The association between autoimmune thyroid diseases and TS should be kept in mind. Both congenital and acquired cardiovascular diseases should be screened in patients with TS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Turner syndrome (TS) is a rare condition with short stature, ovarian dysgenesis and infertility in women as the result of either complete or partial loss of one X chromosome. TS is also associated congenital heart malformations, metabolism disorders such as diabetes mellitus and osteoporosis. Patients with TS are prone to autoimmune disorders among which Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common one [1]. The average age at diagnosis is around 15 years old, but delayed diagnosis is not rare [2]. Here, we reported woman diagnosed with TS at the age of 31, with initial presentation of massive pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade due to very severe hypothyroidism. This case emphasized the association between thyroid diseases and TS and also the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach to care.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old woman was presented at cardiovascular department with facial edema for 2 months and chest tightness for 1 week. Fatigue, palpitation and exertional dyspnea were also reported. She had primary amenorrhea. The patient’s vital signs were: T 36.1℃, P 110 bpm, R 20 bpm, BP 80/70 mmHg. She was 141 cm high and weighed 41 kg. Physical examination revealed short stature, dry skin and coarse hair. Periorbital edema with puffy eyelids were also noticed with mild goiter. Bilateral cardiac enlargement, distant heart sounds and pulsus paradoxus, in combination with hepatomegaly and jugular venous distention were observed. There was no pretibial non-pitting edema. Her hircus and pubic hair was absent. The development of her breast was at 1st Tanner period and gynecological examination revealed infantile vulva. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed low voltage in all leads (Fig. 1a) and the chest X-Ray showed cardiomegaly (Fig. 1b). Massive pericardial effusion was the most protruding finding on echocardiography (33 mm behind the posterior wall of the left ventricle, 6 mm in front of the anterior wall of the right ventricle, 23 mm outside the lateral wall of the left ventricle) (Fig. 1c). The size and structure of the heart were normal and the left ventricular ejection fraction was 63%. Elevated liver enzymes were reported during routine evaluation (Table 1). She was diagnosed with cardiac tamponade based on low systolic pressure, decreased pulse pressure and pulsus paradoxus. Pericardiocentesis was performed and her dyspnea was alleviated after the drainage of pericardial effusion (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). No increases of white blood cell (WBC), percentage of neutrophil or procalcitonin were found (Table 1). Some etiologies for pericardial effusion including tuberculosis, connective tissue diseases and tumors were excluded by measurement of antibodies and biomarkers (Additional file 2: Table S1). Acid-fast staining, bacterial and fungal cultures of the effusion fluid were also negative.

Thyroid function indicated severe hypothyroidism with positive TPOAb (Table 2). Further thyroid ultrasound revealed diffuse inhomogeneous hypo-echoic area. The diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis was made. In view of primary amenorrhea, short stature and the absence of the secondary sexual characteristics, Turner syndrome (TS) was under suspicion. Pelvic ultrasound and sex hormone test were arranged, and absent ovaries, infantile uterus, decreased estrogen and elevated follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) were reported. Further karyotyping of peripheral blood cells revealed a karyotype of 45, X/46, X, i(X) (q10). The patient was diagnosed with mosaic and variant type of TS. Functions of other endocrine glands were tested and no abnormalities were found. Metabolism of glucose, lipid and uric acid (UA) were also evaluated (Table 1). The bone mineral density (BMD) was assessed and the T value of femur and lumbar vertebra (L1 to L4) were -3.5 and -3.6, respectively. Sensorineural deafness was revealed by electrical audition test.

Levothyroxine (L-T4) supplement was initiated (25 μg/d for 3 days, 50 μg/d for 1 week and then 75 μg/d). Estrogen therapy and antiosteoporosis treatment were applied. The TSH was 12.1 μIU/mL with a normal FT4 after one month (Table 2). Meanwhile, resolution of the pericardial effusion was observed on echocardiography (Fig. 1d). L-T4 was increased to 112.5 μg/d and euthyroidism was reported one month later on the telephone follow-up.

Discussion and conclusion

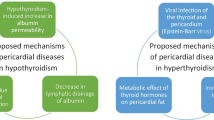

Here, we reported woman diagnosed with TS at the age of 31, with initial presentation of massive pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade due to very severe hypothyroidism. The first difficulty in the diagnosis of this case is to identify that the cause of pericardial effusion is hypothyroidism induced by Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. The etiologies of pericardial effusions are numerous among which hypothyroidism is an uncommon one. The prevalence of pericardial effusion is 3–6% in patients with mild disease and 80% in myxedema [3,4,5]. It’s revealed during cardiovascular evaluation in most cases, but can also be the initial presentation. Increased capillary permeability and reduced lymphatic drainage result in the gradual accumulation of fluid in the pericardial space, though the mechanism hasn’t been fully elucidated [6]. The process usually takes from months to years, as the severity and chronicity of hypothyroidism varies [5, 7]. Moderate and massive effusions are rare [3, 4]. Pericardiocentesis is not necessary in most cases as pericardial effusion disappear within months on L-T4 treatment, with the exception of cardiac tamponade or for differential diagnosis.

The more challenging step was to reveal the underlying TS in this patient after a primary diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and hypothyroidism. This is not only based on her primary amenorrhea and abnormal physical examination, but also based on the alert of increased frequency of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in patients with TS. As the X chromosome contains several immune-related genes [8], the loss of a distinct X chromosome locus could facilitate the development of autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITDs) [9]. As a result, patients with TS have the tendency to develop various autoimmune diseases, including AITDs, type 1 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), among which Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common one [1]. F. Mortensen et al. and Chen et al. reported the increased frequency of AITDs with age [10, 11]. Besides, though euthyroidism is a common clinical phenotype, transition to subclinical or overt hypothyroidism can occur [12], emphasizing the importance of screening for thyroid diseases through life-span [13]. A higher prevalence of AITDs was reported in iso-chromosome Xq population [14, 15]. Further studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanism. Despite the well documented role of estrogen in AITDs, no association between estrogen administration and the occurrence of AIDs was revealed in TS patients [9].

Another noteworthy issue is the screening for cardiovascular abnormalities of TS itself. Both congenital heart malformation and acquired disorder such as ischemic heart disease contributes greatly to morbidity and mortality in patients with TS. Bicuspid aortic valve is the most common congenital malformation with a prevalence of 14–34%. Other common phenotypic characteristics of heart include coarctation of the aorta (7–14%) and aortic dilation/aneurysm (3–42%) [2]. These cardiovascular malformations can occur in isolation or in combination in patients with TS [16,17,18,19]. Hypertension occurs in 50% of patients with TS [2]. Persistent elevation of systolic blood pressure is a risk factor for aortic root dilation and the consequent aortic dissection. The exact genetic and epigenetic mechanism of cardiopathies in TS remains unclear. Acquired heart abnormalities are associated with obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and low estrogen levels. Cardiovascular diseases, both congenital and acquired ones, should be screened in patients with TS.

In conclusion, this case indicated that hypothyroidism should be screened in patients with pericardial effusion, and also emphasized the link between autoimmune thyroid diseases and TS.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- AITDs:

-

Autoimmune thyroid diseases

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- TS:

-

Turner syndrome

References

Aversa T, Messina MF, Mazzanti L, Salerno M, Mussa A, Faienza MF, et al. The association with Turner syndrome significantly affects the course of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in children, irrespective of karyotype. Endocrine. 2015;50(3):777–82.

Gravholt CH, Viuff MH, Brun S, Stochholm K, Andersen NH. Turner syndrome: mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(10):601–14.

Manolis AS, Varriale P, Ostrowski RM. Hypothyroid cardiac tamponade. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(6):1167–9.

Kabadi UM, Kumar SP. Pericardial effusion in primary hypothyroidism. Am Heart J. 1990;120(6 Pt 1):1393–5.

Brent GA, Weetman AP. Hypothyroidism and thyroiditis. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, editors. Williams textbook of endocrinology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. p. 416–9.

Jabbar A, Pingitore A, Pearce SH, Zaman A, Iervasi G, Razvi S. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(1):39–55.

Farooki ZQ, Hoffman WH, Perry BL, Green EW. Myocardial dysfunction in hypothyroid children. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137(1):65–8.

Bianchi I, Lleo A, Gershwin ME, Invernizzi P. The X chromosome and immune associated genes. J Autoimmun. 2012;38(2–3):J187–92.

Stoklasova J, Zapletalova J, Frysak Z, Hana V, Cap J, Pavlikova M, et al. An isolated Xp deletion is linked to autoimmune diseases in Turner syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019;32(5):479–88.

Mortensen KH, Cleemann L, Hjerrild BE, Nexo E, Locht H, Jeppesen EM, et al. Increased prevalence of autoimmunity in Turner syndrome–influence of age. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156(2):205–10.

Chen RM, Zhang Y, Yang XH, Lin XQ, Yuan X. Thyroid disease in Chinese girls with Turner syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;28(1–2):201–5.

Brix TH, Hegedus L. Twin studies as a model for exploring the aetiology of autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76(4):457–64.

Bondy CA, Turner Syndrome Study G. Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: a guideline of the Turner Syndrome Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):10–25.

Elsheikh M, Wass JA, Conway GS. Autoimmune thyroid syndrome in women with Turner’s syndrome–the association with karyotype. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2001;55(2):223–6.

Bakalov VK, Gutin L, Cheng CM, Zhou J, Sheth P, Shah K, et al. Autoimmune disorders in women with turner syndrome and women with karyotypically normal primary ovarian insufficiency. J Autoimmun. 2012;38(4):315–21.

Mazzanti L, Cacciari E. Congenital heart disease in patients with Turner’s syndrome. Italian Study Group for Turner Syndrome (ISGTS). J Pediatr. 1998;133(5):688–92.

Sybert VP. Cardiovascular malformations and complications in Turner syndrome. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1):E11.

Dulac Y, Pienkowski C, Abadir S, Tauber M, Acar P. Cardiovascular abnormalities in Turner’s syndrome: what prevention? Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101(7–8):485–90.

Allybocus ZA, Wang C, Shi H, Wu Q. Endocrinopathies and cardiopathies in patients with Turner syndrome. Climacteric. 2018;21(6):536–41.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81802829) and the Key Program of International Cooperation and Exchanges of Shaanxi, China (No. 2017KW-065). No funding body participated in the design of the study and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WQ and YD collected patient data, obtained consent for publication and wrote the first draft of the article. RS and XZ provided consultation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

The patient gave written informed consent to publish this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1

. The process of pericardiocentesis under the guidance of ultrasound. a Confirmation of the puncture site. b–d Paracentetic needle in the pericardial cavity.

Additional file 2: Table S1

. Screening results for other etiologies of pericardial effusion.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiang, W., Sun, R., Zheng, X. et al. Massive pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade revealed undiagnosed Turner syndrome: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 459 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01728-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01728-2