Abstract

Background

This study is designed to provide detailed knowledge on cognitive impairment after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and its relation to associated factors, and to validate the neurocognitive screening of the Targeted Hypothermia versus Targeted Normothermia after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest trial (TTM2-trial), assessing effectiveness of targeted temperature management after OHCA.

Methods

This longitudinal multi-center clinical study is a sub-study of the TTM2-trial, in which a comprehensive neuropsychological examination is performed in addition to the main TTM2-trial neurocognitive screening. Approximately 7 and 24 months after OHCA, survivors at selected study sites are invited to a standardized assessment, including performance-based tests of cognition and questionnaires of emotional problems, fatigue, executive function and insomnia. At 1:1 ratio, a matched control group from a cohort of acute myocardial infarction (MI) patients is recruited to perform the same assessment. We aim to include 100 patients per group. Potential differences between the OHCA patients and the MI controls at 7 and 24 months will be analyzed with a linear regression, using composite z-scores per cognitive domain (verbal, visual/constructive, working memory, episodic memory, processing speed, executive functions) as primary outcome measures. Results from OHCA survivors on the main TTM2-trial neurocognitive screening battery will be compared with neuropsychological test results at 7 months, using sensitivity and specificity analyses.

Discussion

In this study we collect detailed information on cognitive impairment after OHCA and compare this to a control group of patients with acute MI. The validation of the TTM2 neurocognitive screening battery could justify its inclusion in routine follow-up. Our results may have a potential to impact on the design of future follow-up strategies and interventions after OHCA.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03543371. Registered 1 June 2018

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiac arrest is the abrupt loss of cardiac function and circulation, followed by loss of consciousness. Acute myocardial infarction (MI) is the result of acute coronary ischemia and necrosis. Many out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA) are caused by ventricular arrhythmias complicating acute MI [1]. However, there are many other cardiac and non-cardiac causes of cardiac arrest. The main difference in outcome between acute MI and OHCA is related to the circulatory standstill and subsequent brain injury in OHCA.

Since mortality and morbidity after successful resuscitation from OHCA is mostly due to brain injury [2], neurologic function is an important outcome measure. More than 90% of OHCA survivors have been found to have a favorable neurological outcome [3], when assessed with the commonly used clinician-based outcome scales such as the Cerebral Performance Categories Scale [4] or the modified Rankin Scale [5]. These scales may however miss important information regarding milder impact on cognitive and emotional functions [6].

From a neuropsychological point of view, cognitive impairment and emotional problems are common post-arrest. Cognitive impairment has been observed in about half of OHCA survivors [7,8,9]. A sub-study of the Target Temperature Management trial reported impairments in memory, executive functions or processing speed [10]. These cognitive domains are often impaired post-arrest, but also the most commonly assessed [11]. Others have reported that language and visual/constructive functions may be affected as well [12,13,14]. Brain damage is often diffuse with multiple atrophic areas due to transient global cerebral ischemia [15, 16].

The exact causes of cognitive impairment post-arrest are not yet known. An earlier study from our group found only minor differences between cognition in OHCA survivors and a gender and age-matched group with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) without OHCA after 6 months follow-up [10]. This suggests that cardiovascular risk factors such as vascular degeneration, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, and physical inactivity may contribute to the cognitive impairment in both patient groups. However, these findings need to be corroborated with more sensitive tests. It is also unclear if the minor between-group cognitive differences that were detected persist over a longer time frame, or when using more detailed methods. In this study, we will again use a group of matched acute MI patients as controls. This choice of control group will enable us to separate the effects of the cardiovascular risk factors from cognitive impairment due to hypoxic-ischemic brain injury caused by the OHCA.

The greatest recovery of cognitive function is usually seen in the first 3 months post-arrest, but evidence from several small studies indicates continued improvement in some functions during at least the first year [17, 18]. There is a lack of follow-up with neuropsychological instruments examining several cognitive domains. Earlier studies on cognition after OHCA have either included a smaller number of participants (less than 50), or investigated more patients (100–300) with elementary cognitive assessments or fewer cognitive domains [10, 17, 19].

Cognitive impairment post-arrest correlates with emotional problems [20]. Symptoms of depression have been found in 14 to 45% of all survivors, anxiety in 13 to 61%, and posttraumatic stress in 19 to 27% [21]. Fatigue is closely related to cognitive and emotional function and has been reported in 69% of survivors [22]. The full relationship between fatigue and cognitive impairment, emotional problems and insomnia has yet not been investigated in OHCA survivors.

A cognitive and emotional screening post-arrest is recommended [23, 24] and could identify patients with potential sequelae, thus offering support, rehabilitation and if needed a more extensive assessment. Ideally, a follow-up screening battery should have a low threshold and high sensitivity so that even a slight impairment can be detected for further interventions, such as a detailed neuropsychological evaluation. The Targeted Hypothermia versus Targeted Normothermia after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest trial (TTM2-trial) is an international, multicenter, randomized trial in which a target temperature of 33 °C after OHCA will be compared with a strategy to maintain normothermia and early treatment of fever (≥37.8 °C) during the first 40 h after arrest [25]. The trial will randomize 1900 patients and includes a brief neurocognitive screening of survivors at 6 and 24 months.

This sub-study of the TTM2-trial aims, using a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery, to provide detailed and longitudinal information on cognitive impairment in OHCA survivors in comparison to a control group with acute MI, and the associated factors emotional problems, fatigue, insomnia, and vascular cognitive decline. In addition, this study aims to validate the main TTM2-trial neurocognitive screening, which could be suitable to include in routine follow-up if showing sound psychometric properties.

Hypotheses

-

OHCA survivors will perform significantly worse on neuropsychological tests of cognition compared to a matched cohort of acute MI patients without cardiac arrest.

-

The neurocognitive screening used in the main TTM2-trial will with high sensitivity and adequate specificity identify OHCA survivors with cognitive impairment at 7 months post-arrest.

Methods

Study design

This sub-study of the TTM2-trial is a prospective non-intervention multi-center clinical study, in which selected sites participate.

Participants

Inclusion and exclusion criteria [25] are listed in Table 1.

A control group from a cohort of patients with confirmed and treated acute MI who underwent coronary angiography but without occurrence of cardiac arrest will be recruited at 1:1 ratio. Patients with STEMI and Non-STEMI are eligible as controls. Exclusion criteria for the MI-cohort are the same as for OHCA survivors.

No sample size calculation was performed due to a lack of earlier studies comparing OHCA and MI survivors by using the tests in this study. Instead, our aim is to include a convenience sample of 100 patients per group at 7 months after the event.

Ethical approval, informed consent and trial registration

Ethical applications for the TTM2-trial and this sub-study were approved by all participating countries. All eligible patients at participating sites will receive written and oral information and be asked to take part in the neuropsychological sub-study. Patients will be asked to sign a written informed consent. The TTM2-trial and this sub-study are registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02908308 and NCT03543371).

Procedure

The main TTM2-trial follow-up at 6 months includes a neurocognitive screening [27], which consists of the performance-based instruments Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [28] and Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) [29], the patient-reported Two Simple Questions (TSQ) [30, 31] and the observer-report Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly-Cardiac Arrest (IQCODE-CA) [32, 33].

During the 6-month follow-up of the TTM2-trial, OHCA survivors at participating sites will be invited to partake in this sub-study. At a separate face-to-face appointment at 7 months (preferably within 28 days after regular follow-up) specific to this sub-study, a standardized neuropsychological battery will be administered. The battery comprises performance-based tests of major cognitive domains; verbal, visual/constructive, working memory, episodic memory, processing speed, and executive functions. Instruments will be administered according to guidelines in each manual, including criteria for discontinuing single instruments. The examination will be completed in one single session per follow-up, in a predefined order, and requires approximately 65–85 min with small breaks allowed. Neuropsychologists, psychologists, assistant clinical psychologists, and psychology students (under supervision of a psychologist) will administer the tests after participating in an introductory/training session. Patients and informants are asked to fill out four questionnaires of emotional problems, fatigue, executive dysfunction and insomnia prior to, or after the visit. Three of the questionnaires are self-report measures and will be returned by the patient. The fourth questionnaire is to be completed by an informant, i.e. a relative or close friend. This questionnaire could be returned in a pre-paid envelope by regular mail, in order to maintain the privacy of the informant.

The same neuropsychological test battery will be repeated 24 months post-arrest to investigate to what extent the long-term cognitive outcome of the survivors is accurately predicted by the 7 months examination.

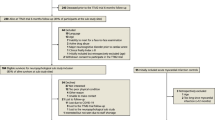

For each participating OHCA-survivor a MI control patient will be recruited per mail and telephone and assessed at one participating site per country (Fig. 1). The MI controls are matched according to the following matching criteria in a descending order: 1) date of cardiac event (all MI within a time frame of ±4 weeks of the CA are accepted); 2) sex; 3) age (best match). For MI control patients, descriptive background information and information on cardiovascular risk factors will be collected through objective measures and structured interview, while the corresponding information for the OHCA survivors will be collected during the regular TTM2 follow-up when applicable (Table 2).

The meeting is preferably performed in a clinical setting, but alternative settings could be considered such as visiting the patient’s place of residence.

Study timeline

The TTM2-trial started on November 18, 2017. The current sub-study started on July 13, 2018. Sites in Sweden, the United Kingdom and Denmark are recruiting. We estimate that the last patients are recruited in 2020, with the final longitudinal follow-up completed 2022.

Study organization

This is an academically initiated study led by researchers at Center for Cardiac Arrest at Lund University.

The study is performed in cooperation with the TTM2 sub-study of Physical Activity After Cardiac Arrest (NCT03543332). If patients choose to participate in this parallel sub-study, the appointments are merged.

Instruments

An overview of the neuropsychological test battery, including reliability coefficients, is found in Table 3, with scores used for computing composite z-scores per cognitive domain appearing in bold. The questionnaires are presented in Table 4.

Verbal domain

The Vocabulary subtest from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV) [39] assesses knowledge of words, abilities to verbalize concepts and retrieve information from the semantic memory.

The Letter Fluency condition of the Verbal Fluency subtest from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) [40] assesses oral productions of words beginning with a specified letter. The Category Fluency condition assesses oral production of words within a designated category. Letter Fluency is proposed to put greater emphasis on executive aspects such as attention allocation and strategic organization than Category Fluency [41]. However, both phonemic and semantic fluency has been reported to load exclusively on a language factor [42].

Visual/constructive domain

The Block Design subtest from the WAIS-IV [39] assesses visuospatial organization. Bonus points are given for a quick, error-free performance. It is relatively free from cultural and educational bias, and is generally sensitive to any kind of cerebral dysfunction [43].

The Matrix Reasoning subtest from the WAIS-IV [39] is a test of non-verbal abstract reasoning and perceptual organization.

Working memory domain

The Digits Forward condition of the Digit Span subtest from the WAIS-IV [39] emphasizes attention efficiency and auditory short-term memory. Digits Backwards emphasizes aspects of working memory, as does Digit Sequencing. The latter conditions are more difficult and rather sensitive to brain injury or deterioration [44].

The Spatial Span subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale – Third Edition (WMS-III) [45] tests visuospatial working memory. The Backward condition is more sensitive to cognitive impairment than the Forward condition, requiring more complex working memory and visual manipulation skills [46].

Episodic memory domain

The Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) [47] is a test of verbal learning and verbal episodic memory, by immediate recall in five trials, delayed recall and recognition of a word list.

In the Logical Memory subtest from the WMS-III [45], the subject is asked to recall two stories immediately and delayed.

The Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R) [48] measures visual learning and visual episodic memory by immediate recall in multiple trials, delayed recall and recognition. There are six different test forms of the BVMT-R with equivalent psychometric properties.

Processing speed domain

The Trail Making Test (TMT) [49, 50] subtask A is a test of visual scanning with a motoric component. The TMT is vulnerable to brain dysfunction in general [43].

The Color-Word Interference Test (CWIT) from the D-KEFS [40] originates from the classic Stroop paradigm [51]. In its first two conditions, the CWIT measures processing speed.

Executive functions domain

The TMT subtask B measures executive aspects such as cognitive flexibility in addition to processing speed [49, 50].

The third condition of the CWIT measures executive functions such as inhibition of a dominant and automatic verbal response, and sustained selective attention [40].

Questionnaires

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a screening for symptoms of anxiety and depression by self-report [52]. The questionnaire consists of seven items for an anxiety subscale and seven items for a depression subscale. Each item is scored on a four-point scale, with responses totaled to obtain two subscale scores. A cut-score of ≥8 per subscale is considered to have a good balance between sensitivity and specificity, with most studies confirming the two-factor structure [53].

The Dysexecutive Questionnaire (DEX) from the Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS) [54] is designed to measure dysexecutive symptoms in everyday situations such as planning problems, distractibility and lack of insight. Items are rated on a five-point scale from zero to four, with higher scores representing greater problem severity. One version of the questionnaire should be completed by the subject (DEX-Self) and another version by an informant (DEX-Other). Discrepancies between the DEX-Self and DEX-Other are indicative of impaired insight [54]. A recent study using exploratory factor analysis on a large clinical and non-clinical sample resulted in confirmation of a one-factor solution for the DEX [55].

The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) measures fatigue in the past week in five dimensions: General fatigue, Physical fatigue, Reduced activity, Reduced motivation, and Mental fatigue [56, 57]. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, with an optional total score obtained by adding up the subscale scores. Higher scores indicate a higher degree of fatigue.

The Minimal Insomnia Symptom Scale (MISS) is an insomnia-screening questionnaire [58]. Items are rated on a five-point scale, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 12 with higher scores indicating more insomnia. Rasch modeling has shown that a cut-score of ≥6 seems to be suited for adults and elderly when identifying presence of insomnia, although clinical criteria recently has been revised [59].

Statistical analyses

Raw scores from all neuropsychological instruments will be converted to standardized z-scores in accordance with normative sample data (based on age and, when applicable, education) for each test. The z-scores will be adjusted for level of education and sex as covariates, when not already adjusted for in the z-score transformation. Test data will be grouped based on the six main cognitive domains measured by the tests (verbal, visual/constructive, working memory, episodic memory, processing speed, executive function). A composite z-score will be computed for each cognitive domain in accordance with Table 3, which also indicates the test scores used for composite z-scores computation. Parametric tests will be used for all analyses because of the z-score standardization and, in accordance with the central limit theorem, a large number of participants per group. A p of <.05 is considered significant for all analyses.

The first hypothesis will be analyzed with a linear regression adjusting for level of education and sex when examining the outcome at 7 months. These results will be reported separately. The analyses will be repeated at 24 months. Composite z-scores per cognitive domain are used as primary outcome measures.

The second hypothesis will be analyzed with a comparison of the OHCA survivors’ results on the neurocognitive screening and the detailed neuropsychological test battery at 7 months’ time. This will be performed by a sensitivity and specificity analysis emphasizing high sensitivity and adequate specificity, including true and false positive rates. Here, patients will be considered to have a cognitive impairment if they meet any of the following criteria on the neuropsychological tests: 1) an impaired composite z-score defined as z ≤ − 1.65 in at least one cognitive domain; 2) z ≤ − 1.65 in at least two scores used for cognitive domain calculation as per Table 3, independent of their domain classification. The proportion of OHCA survivors with impairments on neuropsychological tests will be compared with the proportion of OHCA survivors with indicated cognitive impairment on the neurocognitive screening, by: 1) performance-based instruments (MoCA, SDMT); 2) self and informant-report instruments (TSQ question 2, IQCODE-CA); 3) all four instruments together. As high sensitivity is of importance for a screening, just one score below cut-off on any screening instrument will indicate possible cognitive impairment. Cut-scores for indicated impairment will be < 26 on the MoCA, z ≤ − 1 on the SDMT, ≥3.08 on the IQCODE-CA and the answer “no” to question 2 at the TSQ.

An explorative approach will be used to analyze changes in OHCA survivors’ cognition and emotional problems, fatigue, insomnia, and cardiovascular risk factors from 7 to 24 months.

Missing data will be described and categorized as missing at random and missing not at random.

Discussion

This neuropsychological sub-study of the TTM2-trial is a prospective, longitudinal multi-center clinical study. It is designed to provide detailed knowledge on cognition after cardiac arrest and its relation to emotional problems, fatigue, insomnia, and cardiovascular risk factors. This will provide valuable information as the number of survivors with cognitive impairment is still unclear, and mainly based on results using relatively crude instruments. Survivors will be followed longitudinally until 24 months post-arrest, which has not been done in other studies to date with a corresponding level of detail.

Another aim of this study is to compare patients with and without OHCA. Rather than a group of healthy controls, we have chosen to include a MI cohort as controls, similar to an earlier study from our group [10]. The detailed neuropsychological profile could be of use when tailoring future domain specific rehabilitation interventions for both patient groups. The matched MI controls in this study are recruited in the same country as the OHCA survivors in an effort to bridge any potential differences in demographics and rehabilitation between countries.

The neuropsychological test battery has been designed to provide detailed information about the cognitive function of the patients, while still being feasible to perform in one single session. A total of six cognitive domains are assessed, with a minimum of two tests per cognitive domain to reduce measurement errors. The tests comprising one cognitive domain are intended to measure the same overall cognitive function but different sub-components thereof, which enable analyses of specific test results and functions. The instruments were selected to represent a range of cognitive, behavioral and emotional functions. They are used in clinical practice as well as in research, and the majority of the instruments have previously been used in OHCA studies. All of the neuropsychological tests and most of the questionnaires have sound psychometric norms available.

The results of this study will have potential impact on the planning of future interventions. By validating the commonly used instruments in the neurocognitive screening of the TTM2-trial with neuropsychological instruments, the screening could be sufficient to serve as a model for future OHCA follow-up. Screening instruments with good validity enables the identification of patients in need of more detailed neuropsychological examination, follow-up and rehabilitation.

In addition to the follow-up assessments, the TTM2 population will be well investigated in the acute phase. This includes measures of electroencephalography, cerebral imaging, clinical neurological examination, and biomarkers in serum. Adding the detailed neuropsychological assessment of this study to the analyses, we will be able to investigate the importance of the acute brain injury and the chronic degenerative process post-arrest for neuropsychological functioning over time.

We have chosen to perform the sub-study specific neuropsychological assessment as a separate appointment, rather than at the same time as the regular TTM2 follow-up. This is due to fatigue being a common symptom after OHCA and acquired brain injury in general. Patient weariness and reduced vigilance thus could have implications for neuropsychological test performance [60]. Potential participants, especially those living far away from the study sites, could be more unwilling to partake as a result of this study design. To improve the inclusion ratio and the generalizability of the results, patients are offered a travel reimbursement or that the examination is performed in e.g. the patient’s place of residence.

There is no consensus on how to report cognitive decline in neuropsychological studies. Educational duration is positively correlated with premorbid intellectual capacity [61]. Striving for high specificity, especially in the neuropsychological test battery, we adjust for level of education in our main outcome measures. When comparing the results on the neurocognitive screening with the detailed neuropsychological test battery, the chosen cut-score of z ≤ − 1.65 was inspired by a similar OHCA study [12].

We have refrained from pre-specified comparisons of the neuropsychological function between the 33 °C and normothermia treatment arms. Differences in outcome between the temperature groups will primarily be investigated within the main TTM2-trial with a larger number of participants [27].

As for limitations, the TTM2-trial includes OHCA patients with presumed cardiac cause, however a substantial portion of the patients may have a non-cardiac cause. Although an exclusion of such patients would be possible in this sub-study, recruiting at 7 months post-arrest, we have refrained from this possibility because one of our aims is to validate the main TTM2-trial neurocognitive screening. Since all our MI controls will have a coronary disease, this will cause a discrepancy in our background variables. Still, a similar matching was performed in another study, with relatively equivalent cardiovascular risk factors between groups [10]. Another limitation is possible selection bias, i.e. that those with excellent recovery may be more likely to say yes to being part of the study, skewing the data in a positive way. These tendencies have been observed in other studies [10, 12, 17]. On the other hand, we have information from the main TTM2-trial on the patients declining to participate in this sub-study, facilitating analyses of missing data. Furthermore, the number of studies comparing neuropsychological outcome after OHCA and MI are few, and the tests used in this study are more sensitive than in most earlier studies. Thereby no sample size calculation could be performed for this study; however, the detailed and sensitive information will enable us to explore hypotheses generating trends in a large sample of cardiac arrest survivors and controls.

Availability of data and materials

The data that will support the findings of this study are available from the TTM2 steering group, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the TTM2 steering group.

Abbreviations

- TTM2-trial:

-

Targeted hypothermia versus targeted normothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest trial

- OHCA:

-

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- STEMI:

-

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MoCA:

-

Montreal cognitive assessment

- SDMT:

-

Symbol digit modalities test

- TSQ:

-

Two simple questions

- IQCODE-CA:

-

Informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly-cardiac arrest

- WAIS-IV:

-

Wechsler adult intelligence scale – fourth edition

- D-KEFS:

-

Delis-Kaplan executive function system

- WMS-III:

-

Wechsler memory scale – third edition

- RAVLT:

-

Rey auditory verbal learning test

- BVMT-R:

-

Brief Visuospatial memory test-revised

- TMT:

-

Trail making test

- CWIT:

-

Color-word interference test

- HADS:

-

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

- DEX:

-

Dysexecutive questionnaire

- BADS:

-

Behavioral assessment of the Dysexecutive syndrome

- MFI-20:

-

Multidimensional fatigue inventory

- MISS:

-

Minimal insomnia symptom scale

References

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J. 2018;40(3):237–69.

Dragancea I, Rundgren M, Englund E, Friberg H, Cronberg T. The influence of induced hypothermia and delayed prognostication on the mode of death after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84(3):337–42.

Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33 degrees C versus 36 degrees C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2197–206.

Group BRCTIS. A randomized clinical study of cardiopulmonary-cerebral resuscitation: design, methods, and patient characteristics. Am J Emerg Med. 1986;4(1):72–86.

van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604–7.

Beesems SG, Wittebrood KM, de Haan RJ, Koster RW. Cognitive function and quality of life after successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85(9):1269–74.

Sauve MJ, Doolittle N, Walker JA, Paul SM, Scheinman MM. Factors associated with cognitive recovery after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am J Crit Care. 1996;5(2):127–39.

van Alem AP, de Vos R, Schmand B, Koster RW. Cognitive impairment in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am Heart J. 2004;148(3):416–21.

Tiainen M, Poutiainen E, Oksanen T, Kaukonen K-M, Pettilä V, Skrifvars M, et al. Functional outcome, cognition and quality of life after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia: data from a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23(1):12.

Lilja G, Nielsen N, Friberg H, Horn J, Kjaergaard J, Nilsson F, et al. Cognitive function in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest after target temperature management at 33 degrees C versus 36 degrees C. Circulation. 2015;131(15):1340–9.

Moulaert VRMP, Verbunt JA, van Heugten CM, Wade DT. Cognitive impairments in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2009;80(3):297–305.

Juan E, De Lucia M, Beaud V, Oddo M, Rusca M, Viceic D, et al. How Do You Feel? Subjective Perception of Recovery as a Reliable Surrogate of Cognitive and Functional Outcome in Cardiac Arrest Survivors. Crit Care Med. 46(4):e286–e93.

Dougherty CM. Longitudinal recovery following sudden cardiac arrest and internal cardioverter defibrillator implantation: survivors and their families. Am J Crit Care. 1994;3(2):145–54.

Roine RO, Kajaste S, Kaste M. Neuropsychological sequelae of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1993;269(2):237–42.

Horstmann A, Frisch S, Jentzsch RT, Muller K, Villringer A, Schroeter ML. Resuscitating the heart but losing the brain: brain atrophy in the aftermath of cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2010;74(4):306–12.

Björklund E, Lindberg E, Rundgren M, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Englund E. Ischaemic brain damage after cardiac arrest and induced hypothermia–a systematic description of selective eosinophilic neuronal death. A neuropathologic study of 23 patients. Resuscitation. 2014;85(4):527–32.

Steinbusch CVM, van Heugten CM, Rasquin SMC, Verbunt JA, Moulaert VRM. Cognitive impairments and subjective cognitive complaints after survival of cardiac arrest: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Resuscitation. 2017;120(Supplement C):132–7.

Ørbo M, Aslaksen PM, Larsby K, Schäfer C, Tande PM, Anke A. Alterations in cognitive outcome between 3 and 12 months in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;105:92–9.

Verberne D, Moulaert V, Verbunt J, van Heugten C. Factors predicting quality of life and societal participation after survival of a cardiac arrest: a prognostic longitudinal cohort study. Resuscitation. 2018;123:51–7.

Wilson M, Staniforth A, Till R, das Nair R, Vesey P. The psychosocial outcomes of anoxic brain injury following cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85(6):795–800.

Wilder Schaaf KP, Artman LK, Peberdy MA, Walker WC, Ornato JP, Gossip MR, et al. Anxiety, depression, and PTSD following cardiac arrest: a systematic review of the literature. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):873–7.

Lilja G, Nielsen N, Bro-Jeppesen J, Dunford H, Friberg H, Hofgren C, et al. Return to work and participation in society after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(1):e003566.

Boyce LW, Goossens PH. Rehabilitation after cardiac arrest: integration of neurologic and cardiac rehabilitation. Semin Neurol. 2017;37(01):094–102.

Blennow Nordstrom E, Lilja G. Assessment of neurocognitive function after cardiac arrest. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019;25(3):234–9.

Dankiewicz J, Cronberg T, Lilja G, Jakobsen JC, Bělohlávek J, Callaway C, et al. Targeted hypothermia versus targeted Normothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (TTM2): a randomized clinical trial—rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2019;217:23–31.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight CB, Howard B, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95.

Lilja G, Nielsen N, Ullen S, Blennow Nordstrom E, Dankiewicz J, Friberg H, et al. Protocol for outcome reporting and follow-up in the targeted hypothermia versus targeted Normothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest trial (TTM2). Resuscitation. 2020;150:104–12.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Smith A. Symbol digits modalities test; manual. Los Angeles: Western psychological services; 1982.

Cronberg T, Lilja G, Horn J, Kjaergaard J, Wise MP, Pellis T, et al. Neurologic function and health-related quality of life in patients following targeted temperature management at 33 degrees C vs 36 degrees C after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(6):634–41.

Longstreth WT, Nichol G, Van Ottingham L, Hallstrom AP. Two simple questions to assess neurologic outcomes at 3 months after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: experience from the public access defibrillation trial. Resuscitation. 2010;81(5):530–3.

Blennow Nordström E, Lilja G, Årestedt K, Friberg H, Nielsen N, Vestberg S, et al. Validity of the IQCODE-CA: an informant questionnaire on cognitive decline modified for a cardiac arrest population. Resuscitation. 2017;118:8–14.

Jorm AF, Jacomb PA. The informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol Med. 1989;19(4):1015–22.

Calamia M, Markon K, Tranel D. The robust reliability of neuropsychological measures: meta-analyses of test–retest correlations. Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;27(7):1077–105.

Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Grant I, Temkin NR. Test–retest reliability and practice effects of expanded Halstead–Reitan neuropsychological test battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5(4):346–56.

Martin CR, Lewin RJP, Thompson DR. A confirmatory factor analysis of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in coronary care patients following acute myocardial infarction. Psychiatry Res. 2003;120(1):85–94.

Hellebrekers D, Winkens I, Kruiper S, Van Heugten C. Psychometric properties of the awareness questionnaire, patient competency rating scale and Dysexecutive questionnaire in patients with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2017;31(11):1469–78.

Whitehead L. The measurement of fatigue in chronic illness: a systematic review of Unidimensional and multidimensional fatigue measures. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;37(1):107–28.

Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale – fourth edition (WAIS-IV). San Antonio: Pearson Assessment; 2008.

Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan executive function system (D-KEFS). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2001.

Azuma T. Working memory and perseveration in verbal fluency. Neuropsychology. 2004;18(1):69–77.

Whiteside DM, Kealey T, Semla M, Luu H, Rice L, Basso MR, et al. Verbal fluency: language or executive function measure? Appl Neuropsychol. 2016;23(1):29–34.

Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED, Tranel D. Neuropsychological assessment. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Groth-Marnat G, Wright AJ. Handbook of Psychological Assessment: Wiley; 2016.

Wechsler D. Wechsler memory scale – third edition (WMS-III). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1997.

Wiechmann A. The utility of the spatial span from the Wechsler memory scales in a geriatric population with cognitive impairments. Denton: University of North Texas; 2010.

Rey A. Rey auditory verbal learning test (RAVLT): Western psychological services; 1958.

Benedict RH. Brief Visuospatial memory test – revised (BVMT-R). Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1997.

Reitan RM. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–6.

Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: theory and clinical interpretation. Tucson: Neuropsychology Press; 1985. p. 486.

Stroop JR. Stroop color interference test: multi-health systems, Inc (MHS); 1935.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

Wilson BA, Alderman N, Burgess PW, Emslie H, Evans JJ. Behavioural assessment of the Dysexecutive syndrome (BADS). Bury St. Edmunds: Thames Valley Test Company; 1996.

Pedrero-Pérez EJ, Ruiz-Sánchez-de-León JM, Winpenny-Tejedor C. Dysexecutive questionnaire (DEX): unrestricted structural analysis in large clinical and non-clinical samples. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2015;25(6):879–94.

Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JCJM. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–25.

Lin J-MS, Brimmer DJ, Maloney EM, Nyarko E, BeLue R, Reeves WC. Further validation of the multidimensional fatigue inventory in a US adult population sample. Popul Health Metrics. 2009;7(1):18.

Broman J-E, Smedje H, Mallon L, Hetta J. The minimal insomnia symptom scale (MISS). Ups J Med Sci. 2008;113(2):131–42.

Westergren A, Broman JE, Hellstrom A, Fagerstrom C, Willman A, Hagell P. Measurement properties of the minimal insomnia symptom scale as an insomnia screening tool for adults and the elderly. Sleep Med. 2015;16(3):379–84.

Ziino C, Ponsford J. Vigilance and fatigue following traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12(1):100–10.

Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM. How Much Does Education Improve Intelligence? A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Sci. 2018;29(8):1358–69 (1467–9280 (Electronic)).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Kristofer Årestedt at Linnaeus University, Kalmar, Sweden, for his help with the MISS in this study. We would also like to thank Clinical Nurse Specialist Helen Hill at University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, UK, for patient recruitment and administration.

Funding

The trial is supported by grants from: The Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet), The Skane University Hospital Foundations, The Skane University Hospital Psychology Research and Development Grant, Hans-Gabriel and Alice Trolle-Wachtmeister Foundation for Medical Research, The Gyllenstiernska-Krapperup Foundation, and governmental funding of clinical research within the Swedish National Health System. The funding bodies have no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript. This study protocol was not peer reviewed by any of the funding bodies. Open Access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EBN, GL, SV, TC, and NN designed the sub-study. EBN is the principal investigator. EBN, TC, GL, SV, SU, KH, NN, and HF are the coordinating team. CR, HK, and MPW are national investigators. LE, AMG, TK, MM, SR, MS, and JU are site investigators. EBN, LE, HL, MM, SR, and MS performed the neuropsychological examinations. SU is the trial statistician. EBN, GL, SV and TC drafted the manuscript. All authors revised and gave final approval to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Regional Ethics Committee at Lund University approved ethics applications for the TTM2-trial (reference number 2015/228) and for this sub-study (reference number 2018/127). Written informed consent to participate in the sub-study is obtained before or at the sub-study follow-up meeting by the study examiners.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Blennow Nordström, E., Lilja, G., Vestberg, S. et al. Neuropsychological outcome after cardiac arrest: a prospective case control sub-study of the Targeted hypothermia versus targeted normothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest trial (TTM2). BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 439 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01721-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01721-9