Abstract

Background

Depression often co-exists with non-cardiovascular morbid conditions. Whether this comorbidity increases the risk of cardiovascular disease has so far not been studied. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine if non-cardiovascular morbidity modifies the effect of depression on future risk of CVD.

Methods

Data was derived from the PART study (acronym in Swedish for: Psykisk hälsa, Arbete och RelaTioner: Mental Health, Work and Relationships), a longitudinal cohort study on mental health, work and relations, including 10,443 adults (aged 20–64 years). Depression was assessed using the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) and self-reported data on non-cardiovascular morbidity was assessed in 1998–2000. Outcomes of CVD were assessed using the National Patient Register during 2001–2014.

Results

Both depression (HR 1.5 (95% CI, 1.1, 2.0)) and non-cardiovascular morbidity (HR 2.0 (95% CI, 1.8, 2.6)) were associated with an increased future risk of CVD. The combined effect of depression and non-cardiovascular comorbidity on future CVD was HR 2.1 (95%, CI 1.3, 3.4) after adjusting for age, gender and socioeconomic position. Rather similar associations were seen after further adjustment for hypertension, diabetes and unhealthy lifestyle factors.

Conclusion

Persons affected by depression in combination with non-cardiovascular morbidity had a higher risk of CVD compared to those without non-cardiovascular morbidity or depression alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depressive disorders are a major cause of the non-fatal burden of diseases while ischemic heart disease and stroke are major causes of death [1]. Depression is strongly associated with other types of morbidity [2, 3]. Previous studies have shown this relation both specifically, as well as in combination, with other disorders [4, 5]. Further, depression is reported as a consequence, as well as, a risk factor for other morbidities [6]. For example, depression doubles the risk of future CVD [7,8,9] but also 40% of myocardial infarction patients report depression post-infarction [10]. As depression is linked both to morbidity and to CVD, the combined effect on future risk should be paid attention to in greater depth.

Depression increases the risk of CVD [7,8,9]. Established CVD-related morbidities (CVD risk factors) like hypertension and diabetes increase the risk of CVD [11]. In addition, other kinds of non-cardiovascular morbidity [12], such as rheumatoid arthritis [13] and osteoarthritis [14] also increase the risk of CVD [15]. Non-cardiovascular morbidity is a relatively new term, defined as comorbidities which are not established risk factors for CVD [16]. Generally, it includes respiratory, endocrine, nutritional, renal, hematopoietic, neurological as well as musculoskeletal conditions [17,18,19]. The number of comorbidities, and more importantly non-cardiovascular morbidities, have been reported to increase the severity of CVD (specifically heart failure) and this has been considered an important marker of prognosis in patients with heart failure [20, 21].

Depressive disorders are roughly two-times more prevalent among persons with diabetes, coronary artery disease, HIV infection, and stroke compared to persons not suffering from these diseases [6]. Further, approximately 12–15% of persons with multiple comorbid conditions also suffer from depression [22]. Coexistence of depression and other morbidities can lead to overexpression of somatic symptoms, like fatigue, thus complicating the diagnosis of depression [23]. Additionally, persons with depressive disorders exhibit reduced self-efficacy and “will to function” which might contribute to poor medication adherence and unhealthy lifestyle factors [24]. This results in reduced quality of life, higher costs, and worse health outcomes and requires extensive coordination across various sectors of the health services [3, 25].

The effect of the coexistence of depression and non-cardiovascular morbidity on the risk of CVD, has to our knowledge, been paid less attention. It can be hypothesized that the metabolic or immune-inflammatory pathways might be triggered in depressed patients by additional comorbid conditions which in turn affect the incidence of CVD [26]. This multifaceted coexistence of depression, other somatic and psychiatric morbidity and CVD is a challenge to the clinical care of depressed patients and the lack of clinical guidelines on management might lead to a worse prognosis and additional health problems [27, 28]. Considering this, we aim to increase the knowledge on this topic by determining if non-cardiovascular morbidity modifies the effect of depression on future risk of CVD. In this study we hypothesize that the risk of CVD is higher in depressed individuals with coexisting non-cardiovascular morbidity compared to those without.

Methods

Data was derived from the PART study, a longitudinal cohort study conducted in Stockholm County, Sweden [29]. This study focused on mental health, work and relations among adults living in Stockholm. The data collection took place in 3 waves; 1998–2000-wave 1(W1), 2001–2003-wave 2(W2) and 2010-wave 3(W3). The data was linked to the Swedish health registers through the exclusive identifier “pin number”. All the participants gave written informed consent and answered a posted questionnaire. The questions focused on risks and protective factors for mental health as well as psychiatric rating scales. The Ethical Review Board at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, approved the study (case numbers 96–260, 01–218, 03–302, 2009/880–31, 2012/808–32).

The PART study initially intended to include 19,744 persons of which 19,457 could be reached, and 10,443 answered to the questionnaire at W1 (participation rate 53%). Internal missing was low due to repeated telephone calls. Non-response analyses from W1 was performed using available administrative registers-showing a slightly higher response in women, higher age groups, persons with higher income and education, being born in the Nordic countries and having no previous psychiatric illness [30]. In W2 the participation rate was 83% (n = 8622) and similar associations were seen [31]. A description of the study population according to depression status is shown in Table 1, data of 10,341 participants were available for analysis at baseline. For the purpose of this study participants with a current or previous history of myocardial infarction, angina or stroke (n = 267, 2.6%) were excluded leaving a total sample of 10,074 participants.

Depression

Depression was measured as the index disease and assessed using the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) from W1 and W2. Participants with MDI score above 20 in either of the two waves were considered as depressed. The MDI has shown high validity in both clinical and non-clinical samples, including the PART study [32,33,34].

Non-cardiovascular morbidity

Non-cardiovascular conditions [35, 36] were derived from self-reports asking the following question; Indicate if you are presently or previously been diagnosed or treated by a doctor or hospitalized for any of the following conditions? neurological disorders (brain disease, spinal cord, nerve fibers, headache), endocrinological disorders (goiter, thyroid disease or metabolic disease), respiratory disorders (asthma, chronic bronchitis or other lung disease), gastrointestinal disorders (dyspepsia, bowel or liver disease), kidney or urinary tract disorders, genital disorders, serious infections, tumors (benign or malignant), rheumatological disorders, other heart diseases (except ischemic heart diseases), severe skin disorders and psychiatric disorders (other than depression). Presence of any of these was considered as non-cardiovascular morbidity.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was evaluated using hospital discharge diagnoses classified according to the International Classification of Disease (ICD) in the National Patient Register (NPR) during 2001 to 2014, including the following diagnoses [37, 38]: ischemic/hypertensive heart disease; hypertensive diseases (ICD10: I11–13), ischemic heart diseases (ICD10: I20–25), heart failure (ICD10: I50), other peripheral vascular diseases, embolism and thrombosis (ICD10: I73–74) and stroke (ICD10: I60–67 and I69).

Covariates

Age, gender, socioeconomic position (SEP) [39], hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hazardous alcohol use, body mass index (BMI) and physical inactivity were considered as covariates [40,41,42]. Physical inactivity and smoking were only recorded in W2 and hence have slightly higher levels of missing values. Age was divided into four categories: 20–30, 31–40, and 41–52 and > 52 years. SEP was measured by using the Nordic Standard Occupational Classification (NSOC) of 1989 and classified into five groups according to Statistics Sweden’s Goldthorpe-Eriksson classification scheme: high/intermediate level salaried employees; assistant non-manual employees; skilled workers; unskilled workers; and self-employed (including farmers). As a substantial number of participants (n = 2488) were not currently employed at the time of assessment, we used their daily reported activity and created additional categories; including those who were retired or students. Participants were considered as physically inactive if they reported exercising habitually less than three times a week. Self-reported measures on hypertension and diabetes mellitus were used from wave 1. They were questioned as follows; “Are you currently or have you previously been diagnosed or treated by a doctor or hospitalized for hypertension or diabetes.” Smoking habits were classified as regular smoker, occasional smoker, previous smoker and never smoker. Hazardous alcohol use was assessed in W1 or W2 by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [43]. The AUDIT used a cutoff of ≥8 for men and ≥ 6 for women to classify alcohol intake into hazardous alcohol intake and no hazardous alcohol intake [44]. .Participants were considered to have hazardous alcohol intake for the wave they scored higher on the AUDIT.

Statistical analyses

Mean (SD) was used to report continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Chi-square test was used to assess group differences.

Imputation of missing values for MDI was done using the mean value of the questions in the answered items. This was done when there were missing responses for one or two out of the 10 questions. Among those who participated in W1 or W2, if there were missing for more than two questions, the response was left as missing (0.2% (n = 23) in W1 and 1.4% (n = 121) in W2). A trivial percentage 0.2% (n = 21) of the participants did not respond to the questions on comorbid conditions. Smoking and physical inactivity were measured in W2 and as 16% (n = 1719) did not participate in W2, evidence was missing for them, additionally 146 participants did not respond to questions on smoking and 112 did not respond to questions on physical inactivity. No imputations were performed for variables other than MDI.

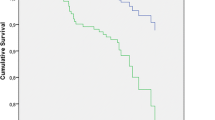

Cox regression models were built to estimate hazard ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Participants were followed from 1st of January 2001 to 31st of December 2014 and endpoints considered were time of IHD, stroke or death, or end of follow up. Time to event was calculated in years = time of event (date of admission to hospital for CVD event) -start of follow-up for those who had an event, and end of follow-up - start of follow-up for those who did not have a cardiovascular event. Cox regression models were adjusted for age, gender and SEP in model 1 and additionally for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, physical inactivity, BMI and hazardous alcohol intake in model 2.

Interaction was measured on an additive scale as it is appropriate for assessing public health importance [45]. Four dummy variables of depression and non-cardiovascular morbidity were created to measure interaction. These were; no depression and no non-cardiovascular morbidity (reference category), depression with no non-cardiovascular morbidity, no depression but with non-cardiovascular morbidity, and depression with non-cardiovascular morbidity. Synergy index (S) is used to measure the effect of binary interaction among risk factors on the outcome [46] and to determine if additive interaction was present. S = 1 means no interaction or exactly additivity; S > 1 means positive interaction or more than additivity; S < 1 means negative interaction or less than additivity. S can range from 0 to infinity [47]. SAS 9.3 and SPSS version 19.11 and were used for the statistical analyses.

Results

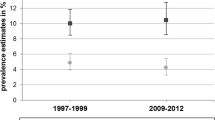

The overall prevalence of depression was 14.6% and of non-cardiovascular morbidity 13.1%. Among those who were depressed, 21.7% had non-cardiovascular morbidity. At follow up 6.5% had a CVD diagnosis; 4.2% had ischemic heart diseases and 2.9% had stroke.

Distribution of the specific non-cardiovascular conditions, stratified by depression status, is shown in Table 2. The most common non-cardiovascular conditions reported were respiratory disorders: 3.1%; followed by endocrinological disorders (other than diabetes mellitus): 1.8%; and rheumatologic disorders: 1.5%. A small proportion of the participants (1.6% (n = 164)) also reported psychiatric disorders (other than depression).

Depression, as reported previously [7], and non-cardiovascular morbidity were associated with increased risk of CVD (HR 1.5 (95% CI 1.2, 2.0) and HR 2.0 (95% CI 1.8, 2.6) respectively).

The interaction effect of non-cardiovascular morbidity and depression on risk of CVD is demonstrated in Table 3, showing hazard ratios for the combined effect of depression and non-cardiovascular morbidity on the risk of future CVD. Among those who were depressed without and with non-cardiovascular morbidity, the HR (95% CI) for future CVD were 1.4 (95% CI 1.1, 2.0) and 2.1 (95% CI 1.3, 3.4) respectively, adjusted for age, gender and SEP. The associations remained statistically significant after further adjustment for diabetes, hypertension, physical inactivity, smoking, BMI and hazardous alcohol use. The synergy index for additive interaction was 1.5 (95% CI 1.0, 2.2) after considering all covariates.

Discussion

In this large population-based study we found that coexistence of depression and non-cardiovascular morbid conditions doubled the risk of CVD. This additive interaction between depression and non-cardiovascular morbid conditions is also supported by the synergy index. The effect remained after adjusting for unhealthy lifestyle factors and other previously reported cardiovascular risk factors.

Several studies demonstrate an association between depression and CVD [7,8,9] as well as with other morbid conditions [3, 6, 48]. Studies have additionally shown that having an increased level of non-cardiovascular morbidity worsens the outcome of cardiovascular diseases like myocardial infarction and heart failure [49,50,51,52]. .However, the results of these studies are limited by the cross-sectional designs and have not assessed the interplay with depression. There are some studies which have focused on depression with specific comorbidities leading to CVD. For example, in a longitudinal study, patients with depression and rheumatoid arthritis were 1.4 times more likely than non-depressed rheumatoid arthritis patients to have myocardial infraction at follow-up [53]. To the best of our knowledge, only one previous study has focused on depression, comorbidity and CVD. The study included 6394 subjects who participated in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) conducted between 1971 and 1975 and later followed-up between 1982 and 1984 [54]. Depression and prevalent chronic medical conditions were assessed at baseline and participants were followed up for CVD mortality and incident medical conditions. The results showed that having more severe depressive symptoms increased the risk of CVD mortality at follow-up (HR 1.5 (95% CI 1.2, 1.8)), however the risk attenuated when taking into account demographics, lifestyle behaviors, prevalent and incident chronic medical conditions (HR 1.1 (95% CI 0.9, 1.4)). The study therefore concluded that the association between depression and CVD mortality was partially mediated by prevalent/incident comorbidity. Our study is in partial agreement with this study, showing that depression with coexisting comorbidity increased the risk of CVD. The reason for only partial agreement can be that our study mainly assessed non-cardiovascular morbidity at baseline and found that its existence in the depressed increased the incidence of CVD (HR 2.1 (95% CI 1.3–3.4)). Additionally, there are some important differences that make it difficult to compare results, including differences in assessment of depression, type of comorbid conditions and CVD outcome. Also, we considered non-cardiovascular morbidity as an effect modifier whereas the former study adjusted for it in the analyses. This led to underestimation of the risks in the former study as adjusting for comorbid conditions might have accounted for most of the association between depression and CVD. Also, the former study included conventional CVD risk factors (e.g. diabetes, hypertension) in their assessment of comorbidity, whereas we considered only non-cardiovascular ones.

One potential explanation for our increased risk of CVD in depressed people with coexisting non-cardiovascular morbidity could be poorer treatment adherence [55]. Lack of coordination between physicians may contribute to patients’ non-compliance of drugs prescribed for both comorbid and depressive conditions [56]. Therefore, a combined, integrated clinical care and self-management program to prevent and manage multi-morbidity including depression is needed [57]. Also, due to polypharmacy for different comorbid conditions, there might be drug-drug interactions leading to adverse clinical outcomes [58]. The underlying mechanisms shared between depression and comorbidity leading to CVD are not well established. Inflammation indicated by circulating levels of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen may be an important biological mechanism through which chronic medical conditions are linked to disorders in later life [59]. Inflammation is also an underlying shared mechanism between depression and CVD [60]. It might be that in depressed people, an additional comorbid condition triggers a pathway of inflammation contributing to the risk of CVD [26].

The strengths of this study lie in its longitudinal design, population-based large sample and use of validated instruments for assessing depression and register-based CVD outcomes. Our study has also some limitations that should be acknowledged. The baseline response rate was low in wave 1 (53%) [30, 31]. People severely affected by psychiatric disorders including major depression probably did not participate and this might have led to an underestimation of the magnitude of the problem and resulted in limited external validity. Hence, results cannot be generalized to patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Although we did have a relatively large proportion (5 .6%, n = 587) of participants with severe depression in the PART cohort [7], we did not have enough power to analyze a potential dose-response relationship. One limitation is the assessment of comorbidity which was based on self-reports and hence prone to recall bias due to lack of memory and may have resulted in non-differential misclassification thus moving the estimates towards the null. Previous studies have shown high validity of self-reporting for assessing comorbidity [61] but more objective measurements of the comorbid conditions with objective diagnostic scales [62], or diagnostic tests [63], could have further strengthened the assessments and improved the validity of the study. Since both depression and non-cardiovascular morbidity were measured at the same point in time, we cannot clarify the temporality between the two exposures. Establishing temporality is a challenge as DSM-5 manual also debates temporality and has categorized depression with chronic conditions separately [64]. Although this study was able to adjust for many covariates, it did not offer the possibility to adjust for mediators like dyslipidemia, blood glucose, type and use of antidepressants and treatment compliance. Information on antidepressant use is important in this relation as antidepressants like tricyclic antidepressants are known to increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmia which in turn may contribute to the studied CVDs [65, 66]. However instinctive expectation of effect decomposition of mediators might nullify the total effect of the exposure and outcome [67]. Although we were able to show a doubled risk for CVD when both depression and non-cardiovascular morbidity were present, the synergy index > 1 indicated additive interaction but due to the borderline confidence interval, the results need to be replicated in future larger studies.

Conclusion

In this study, we showed that persons affected by depression in combination with non-cardiovascular morbidity had a higher risk of CVD compared to those without non-cardiovascular morbidity or depression alone. The additive interaction we found needs to be replicated in future longitudinal studies and these should also be designed to address the temporality in the occurrence of depression and comorbid conditions. From a clinical perspective, future research needs to address the identification of concomitance and to design interventions encompassing simultaneous treatment of comorbidities and depression to prevent future CVD.

Availability of data and materials

Data are ethically restricted for patient privacy concerns. However, de identified, participant level data can be obtained pending ethical approval. Please send requests for a Minimal dataset to Dr. Yvonne Forsell; yvonne.forsell@aku.edu.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- ICD:

-

International classification of disease

- MDI:

-

Major depression inventory

- NSOC :

-

Nordic standard occupational classification

- PART :

-

Psykisk hälsa, Arbete och RelaTioner, acronym in Swedish for: mental health, work and relationships

- SEP:

-

Socioeconomic position

References

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59.

Stein MB, Cox BJ, TO A, Belik SL, Sareen J. Does co-morbid depressive illness magnify the impact of chronic physical illness? A population-based perspective. Psychol Med. 2006;36(5):587–96.

Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the world health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–8.

Tsiachristas A, van Ginneken E, Rijken M. Tackling the challenge of multi-morbidity: actions for health policy and research. Health Policy. 2018;122(1):1–3.

Eaton WW, Armenian H, Gallo J, Pratt L, Ford DE. Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes. A prospective population-based study. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(10):1097–102.

Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):216–26.

Almas A, Forsell Y, Iqbal R, Janszky I, Moller J. Severity of depression, anxious distress and the risk of cardiovascular disease in a Swedish population-based cohort. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140742.

Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):613–26.

Pan A, Sun Q, Okereke OI, Rexrode KM, Hu FB. Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1241–9.

Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression, mortality, and medical morbidity in patients with coronary heart disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):241–7.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–52.

Taneva E, Bogdanova V, Shtereva N. Acute coronary syndrome, comorbidity, and mortality in geriatric patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1019:106–10.

Crowson CS, Liao KP, Davis JM 3rd, Solomon DH, Matteson EL, Knutson KL, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2013;166(4):622–8.e1.

Fernandes GS, Valdes AM. Cardiovascular disease and osteoarthritis: common pathways and patient outcomes. Eur J Clin Investig. 2015;45(4):405–14.

Tran J, Norton R, Conrad N, Rahimian F, Canoy D, Nazarzadeh M, et al. Patterns and temporal trends of comorbidity among adult patients with incident cardiovascular disease in the UK between 2000 and 2014: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002513.

Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2581–7.

Metra M, Zaca V, Parati G, Agostoni P, Bonadies M, Ciccone M, et al. Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular comorbidities in patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2011;12(2):76–84.

Wang PS, Avorn J, Brookhart MA, Mogun H, Schneeweiss S, Fischer MA, et al. Effects of noncardiovascular comorbidities on antihypertensive use in elderly hypertensives. Hypertension. 2005;46(2):273–9.

Sharma A, Zhao X, Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Felker GM, et al. Trends in noncardiovascular comorbidities among patients hospitalized for heart failure: insights from the get with the guidelines-heart failure registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(6):e004646.

van Deursen VM, Urso R, Laroche C, Damman K, Dahlstrom U, Tavazzi L, et al. Co-morbidities in patients with heart failure: an analysis of the European Heart Failure Pilot Survey. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(1):103–11.

Rushton CA, Satchithananda DK, Jones PW, Kadam UT. Non-cardiovascular comorbidity, severity and prognosis in non-selected heart failure populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;196:98–106.

Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Outcome of depression in psychiatric settings. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(3):297–304.

Sayar K, Kirmayer LJ, Taillefer SS. Predictors of somatic symptoms in depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(2):108–14.

Himelhoch S, Weller WE, Wu AW, Anderson GF, Cooper LA. Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2004;42(6):512–21.

Findley P, Shen C, Sambamoorthi U. Multimorbidity and persistent depression among veterans with diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension. Health Soc Work. 2011;36(2):109–19.

Pizzi C, Manzoli L, Mancini S, Bedetti G, Fontana F, Costa GM. Autonomic nervous system, inflammation and preclinical carotid atherosclerosis in depressed subjects with coronary risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(1):292–8.

Fortin M, Soubhi H, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity's many challenges. BMJ. 2007;334(7602):1016–7.

Barbero U, D'Ascenzo F, Nijhoff F, Moretti C, Biondi-Zoccai G, Mennuni M, et al. Assessing Risk in Patients with Stable Coronary Disease: When Should We Intensify Care and Follow-Up? Results from a Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies of the COURAGE and FAME Era. Scientifica (Cairo). 2016;2016:3769152.

Hällström T, Damström Thakker K, Forsell Y, Lundberg I, Tinghög P. The PART study. .A population based study of mental health in the Stockholm County: study design. Phase l (1998–2000).; 2003.

Lundberg I, Damstrom Thakker K, Hallstrom T, Forsell Y. Determinants of non-participation, and the effects of non-participation on potential cause-effect relationships, in the PART study on mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(6):475–83.

Bergman P, Ahlberg G, Forsell Y, Lundberg I. Non-participation in the second wave of the PART study on mental disorder and its effects on risk estimates. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56(2):119–32.

Forsell Y. The major depression inventory versus schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry in a population sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(3):209–13.

Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Problem solving therapies for depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(1):9–15.

Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, Martiny K, Bech P. The internal and external validity of the major depression inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychol Med. 2003;33(2):351–6.

Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):357–63.

Schellevis FG, van der Velden J, van de Lisdonk E, van Eijk JT, van Weel C. Comorbidity of chronic diseases in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):469–73.

Nilsson AC, Spetz CL, Carsjo K, Nightingale R, Smedby B. Reliability of the hospital registry. The diagnostic data are better than their reputation. Lakartidningen. 1994;91(7):598–603–5.

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450.

Seifert CL, Poppert H, Sander D, Feurer R, Etgen T, Ander KH, et al. Depressive symptoms and the risk of ischemic stroke in the elderly--influence of age and sex. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50803.

Thurston RC, El Khoudary SR, Derby CA, Barinas-Mitchell E, Lewis TT, McClure CK, et al. Low socioeconomic status over 12 years and subclinical cardiovascular disease: the study of women's health across the nation. Stroke. 2014;45(4):954–60.

Roest AM, Zuidersma M, de Jonge P. Myocardial infarction and generalised anxiety disorder: 10-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(4):324–9.

Eurelings LS, Ligthart SA, van Dalen JW, Moll van Charante EP, van Gool WA, Richard E. Apathy is an independent risk factor for incident cardiovascular disease in the older individual: a population-based cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;29:454–63.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804.

Kallmen H, Wennberg P, Berman AH, Bergman H. Alcohol habits in Sweden during 1997-2005 measured with the AUDIT. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61(6):466–70.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Walker AM. Concepts of interaction. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112(4):467–70.

Moore JH, Williams SM. New strategies for identifying gene-gene interactions in hypertension. Ann Med. 2002;34(2):88–95.

Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ, Groenwold RH, Klungel OH, Rovers MM, Grobbee DE. Estimating measures of interaction on an additive scale for preventive exposures. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(6):433–8.

Kravitz RL, Ford DE. Introduction: chronic medical conditions and depression--the view from primary care. Am J Med. 2008;121(11 Suppl 2):S1–7.

Schmidt M, Jacobsen JB, Lash TL, Botker HE, Sorensen HT. 25 year trends in first time hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction, subsequent short and long term mortality, and the prognostic impact of sex and comorbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e356.

Radovanovic D, Seifert B, Urban P, Eberli FR, Rickli H, Bertel O, et al. Validity of Charlson comorbidity index in patients hospitalised with acute coronary syndrome. Insights from the nationwide AMIS plus registry 2002-2012. Heart. 2014;100(4):288–94.

Lund LH, Donal E, Oger E, Hage C, Persson H, Haugen-Lofman I, et al. Association between cardiovascular vs. non-cardiovascular co-morbidities and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(9):992–1001.

Lawson CA, Solis-Trapala I, Dahlstrom U, Mamas M, Jaarsma T, Kadam UT, et al. Comorbidity health pathways in heart failure patients: a sequences-of-regressions analysis using cross-sectional data from 10,575 patients in the Swedish heart failure registry. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002540.

Scherrer JF, Virgo KS, Zeringue A, Bucholz KK, Jacob T, Johnson RG, et al. Depression increases risk of incident myocardial infarction among veterans administration patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(4):353–9.

Atlantis E, Shi Z, Penninx BJ, Wittert GA, Taylor A, Almeida OP. Chronic medical conditions mediate the association between depression and cardiovascular disease mortality. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(4):615–25.

Wong MC, Liu J, Zhou S, Li S, Su X, Wang HH, et al. The association between multimorbidity and poor adherence with cardiovascular medications. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(2):477–82.

Page RL 2nd, Lindenfeld J. The comorbidity conundrum: a focus on the role of noncardiovascular chronic conditions in the heart failure patient. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2012;14(3):276–84.

Fisher EB, Chan JC, Nan H, Sartorius N, Oldenburg B. Co-occurrence of diabetes and depression: conceptual considerations for an emerging global health challenge. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(Suppl):S56–66.

Braunstein JB, Anderson GF, Gerstenblith G, Weller W, Niefeld M, Herbert R, et al. Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(7):1226–33.

Friedman EM, Christ SL, Mroczek DK. Inflammation partially mediates the Association of Multimorbidity and Functional Limitations in a National Sample of middle-aged and older adults: the MIDUS study. J Aging Health. 2015;27(5):843–63.

Empana JP, Sykes DH, Luc G, Juhan-Vague I, Arveiler D, Ferrieres J, et al. Contributions of depressive mood and circulating inflammatory markers to coronary heart disease in healthy European men: the prospective epidemiological study of myocardial infarction (PRIME). Circulation. 2005;111(18):2299–305.

Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients' self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1407–17.

Deyo RA, Centor RM. Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(11):897–906.

Hassanzadeh J, Rezaianzadeh A. Assessing the validity of diagnostic tests. Iran J Med Sci. 2012;37(1):2.

Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American psychiatric pub; 2013.

Hamer M, Batty GD, Seldenrijk A, Kivimaki M. Antidepressant medication use and future risk of cardiovascular disease: the Scottish health survey. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(4):437–42.

Grace SL, Medina-Inojosa JR, Thomas RJ, Krause H, Vickers-Douglas KS, Palmer BA, et al. Antidepressant use by class: association with major adverse cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychother Psychosom. 2018;87(2):85–94.

Richiardi L, Bellocco R, Zugna D. Mediation analysis in epidemiology: methods, interpretation and bias. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(5):1511–9.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding for the PART was provided by the Swedish Research Council (to YF, the Stockholm County Council), the Karolinska Institutet Faculty Funds (to YF). Support to the PhD student was provided by Faculty Development Award, Aga Khan University Karachi, Pakistan. The funding bodies did not have any role in the design of the study, data collection and analysis, nor on the interpretation and dissemination of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study idea was conceived by AA, YF and JM and contributed equally to the conception and design of the study. AA performed the statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RI and AL provided AA with input and support on the cardiovascular respectively comorbidity components of the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and made significant contributions to drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and substantially revised the manuscript for intellectual content, and approved the last version of the manuscript.

Authors’ information

The author AA acquired a PhD in 2019 from the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, and this study was part of her PhD thesis. She works as an internist with primary affiliation with Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Review Board at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, approved the study (case numbers 96–260, 01–218, 03–302, 2009/880–31, 2012/808–32). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Almas, A., Moller, J., Iqbal, R. et al. Does depressed persons with non-cardiovascular morbidity have a higher risk of CVD? A population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 19, 260 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1252-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1252-7