Abstract

Background

South Asians have disproportionately high rates of cardiovascular disease. Dyslipidemia, a contributing factor, may be influenced by lifestyle, which can vary by religious beliefs. Little is known about South Asian religions and associations with dyslipidemia.

Methods

Cross-sectional analyses of the MASALA study (n = 889). We examined the associations between religious affiliation and cholesterol levels using multivariate linear regression models. We determined whether smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, and dietary pattern mediated these associations.

Results

Mean LDL was 112 ± 32 mg/dL, median HDL was 48 mg/dL (IQR:40–57), and median triglycerides was 118 mg/dL (IQR:88–157). Muslims had higher LDL and triglycerides, and lower HDL, while participants with no religious affiliation had lower LDL and higher HDL. The difference in HDL between Muslims and those with no religious affiliation was partly explained by alcohol consumption.

Conclusions

Religion-specific tailoring of interventions designed to promote healthy lifestyle to reduce cholesterol among South Asians may be useful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dyslipidemia is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), and is a major public health challenge [1,2,3]. Dyslipidemia is characterized by higher concentrations of total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides, and lower HDL-cholesterol [4, 5]. Compared to other racial/ethnic groups, South Asians (individuals from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka) have higher rates of dyslipidemia-related conditions, such as atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. South Asians have become one of the fastest growing immigrant groups in the U.S., with nearly 5.1 million South Asians in the U.S. currently [1, 14].

While certain individuals are genetically predisposed to dyslipidemia-related conditions, the high prevalence of dyslipidemia among South Asians may also be driven by acculturation, socio-economic status, and lifestyle behaviors such as high fat and calorie dense diets and physical inactivity [4, 5, 15,16,17,18]. Cultural and religious norms often influence lifestyle behavior choices [15, 19,20,21,22,23]. In a prior study, religious affiliation was positively associated with healthy lifestyle choices [24]. For example, Seventh-day Adventists (SDA) have traditionally had lower rates of chronic diseases, including obesity, CVD and diabetes than the general population because of their prescriptive lifestyle [25]. Along with adequate exercise and rest, Adventists are encouraged to adopt a healthful lifestyle including a vegetarian diet, avoiding caffeine-containing beverages, rich and highly refined foods, hot condiments and spices, and abstaining from alcohol, tobacco and narcotics [25, 26]. A 30-day diet and lifestyle intervention (physical activity daily, stress management techniques, sleep, and life balance) showed greater improvement in blood lipids and other health outcomes in non-SDA compared to SDA because the SDA had healthier behaviors at baseline [25].

Among religions practiced in South Asia, Islam prohibits alcohol due to the risk of alcohol-related diseases, and pork ingestion [27, 28]. Muslims believe that CVD is significantly decreased through these lifestyle promotions [29, 30]. Hinduism promotes a sattvic diet that is meant to include food and eating habits that are “pure, essential, natural, vital, energy-containing, clean, conscious, true, honest, wise” [15, 31, 32] such as seasonal foods, fruits, dairy products, nuts, seeds, oils, ripe vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and non-animal based proteins [33]. Sikhism prohibits tobacco use, discourages alcohol use, and promotes yoga and meditation [34].

Religion has already been proposed and used as a means of enhancing patient and community awareness of diabetes [34]. Incorporation of religion and culture-specific motivational and therapeutic strategies improves patient–physician communication and bonding, facilitates appropriate patient-centered care, and provides a framework upon which desired outcomes can be achieved [35,36,37,38]. Behavioral interventions targeting religion-specific modifiable factors for dyslipidemia—namely diet and physical activity—hold most promise for addressing these disproportionate disease rates among South Asians [15, 39, 40]. Using data from the Mediators in Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study, we examined the association between religious affiliation and cholesterol levels among a religiously heterogeneous South Asian immigrant cohort. We also determined whether lifestyle behaviors such as smoking, alcohol intake, the amount of physical activity and dietary patterns would explain these associations. We hypothesized that different religious affiliations within the heterogeneous South Asian community may affect dietary practices and physical activity differentially due to religion-specific lifestyle prescriptions/proscriptions which would be associated cholesterol levels [41,42,43,44].

Methods

Data source

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of the baseline data from the MASALA study. The MASALA study is a community-based prospective cohort of 906 South Asians, free of CVD at baseline, enrolled from two geographical regions in the U.S. between October 2010 and March 2013 [6]. The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and Northwestern University (NWU) institutional review boards approved the protocol. Missing and refused observations were dropped from our multivariable analyses and thus the total sample size for this analysis was 889. There were 3 participants who had missing values for all cholesterol outcome variables. Another 7 participants were missing calculated LDL values, and an additional 14 were missing dietary pattern data. Measurements obtained at baseline included (but not limited to) socio-demographic information, lifestyle factors, anthropometric measurements, and fasting blood samples for biochemical risk factors [42].

Cholesterol levels

After a requested 12-h fast, phlebotomy was conducted by certified phlebotomists or nurses to determine lipoprotein and lipid levels in milligrams per deciliter [6]. Total cholesterol, HDL and triglycerides were measured by enzymatic methods (Quest, San Jose, CA) and plasma LDL was consequently estimated using the Friedewald formula [45].

Religious affiliation

Participants self-reported their religious affiliation with response items that included Hinduism, Sikhism, Islam, Jainism, Christianity, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, or none. We collapsed these religious affiliations into fewer categories. We created a category combining those who self-reported Hinduism or Jainism because they have similar religious dietary proscriptions. Due to small numbers we classified participants who reported Christianity, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and those who reported more than one affiliation as “Other”.

Covariates/mediators

We included socio-demographic characteristics and cholesterol medication use as covariates, and smoking, alcohol intake, the amount of physical activity and dietary patterns as mediators in our analysis. Socio-demographic characteristics included age, sex, years of life spent in the U.S., overall health status, marital status, educational attainment, health care access, insurance status and family income. Cholesterol medication use was assessed by medication inventory and included statin, fibrate, niacin, ezetimibe, or colesevelam use.

Smoking status was assessed based on whether the participant had never smoked, was a former smoker or currently smoked cigarettes. We categorized alcohol intake based on the number of alcoholic beverages consumed per week. Physical activity was assessed using the Typical Week’s Physical Activity Questionnaire [46] and was calculated as Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET)-minutes of physical activity per week. Diet was assessed using the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic Groups (SHARE) Food Frequency Questionnaire, which was developed and validated in South Asians in Canada, and included items unique to the South Asian diet [42, 47, 48]. Principal component analysis identified three distinctive dietary patterns; each respondent was assigned to the pattern for which he/she had the highest factor score [49]. The three major dietary patterns observed were Western (alcohol, coffee, eggs, fish, pasta, pizza, poultry, red meat, refined grains, vegetable oil; negative for whole grain, low-fat dairy, legumes), Sweets and Refined Grains (positive for added fat, butter/ghee, fried snacks, fruit-juice, high-fat dairy, sugar-sweetened beverages, legumes, potatoes, refined grains, rice, snacks, sweets, whole grains; negative for vegetable oil and nuts), and Fruits and Vegetables (positive for fruit, fruit juice, legumes, low-fat dairy, vegetable oil, nuts, vegetables, whole grains) [49].

Statistical analysis

We described the prevalence of baseline characteristics in the study population. Between-group comparisons utilized chi-squared testing. Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to estimate the independent associations of religious affiliation with LDL, HDL and triglyceride levels with the base models adjusted for age, sex and cholesterol medication use. Variables with biological plausibility were included in the multivariate model. Then, to examine potential mediation of the effects of religious affiliation by lifestyle behaviors, we added smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity and dietary pattern to the base model. Finally, we tested for modification of the effects of religious affiliation by sex and none were found. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

In fitting the linear models, we log-transformed LDL, HDL and triglyceride levels to meet normality assumptions, so that exponentiated coefficient estimates are interpretable as percentage between-group differences in average cholesterol levels. We calculated and presented adjusted means before and after the addition of mediators, using standardization. We performed pair-wise comparisons to analyze differences in cholesterol levels between groups.

The analysis was conducted using STATA/SE Version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

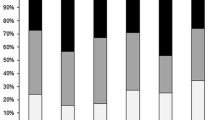

Of the 889 South Asians in this analysis, the average age was 55 ± 9 years, 53% were men, and 29% were taking cholesterol medications (Table 1). Cholesterol medication use did not differ significantly by religious affiliation (p = 0.36). On average, half of participants’ lives were spent in the U.S. The majority of participants identified with Hinduism/Jainism (74%), followed by Sikhism (8%), Islam (7%), other religious affiliations (6%), and no religious affiliations (6%). A majority of the participants had never smoked (83%) and did not consume alcohol on a weekly basis (67%). Smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, and dietary pattern differed significantly by religious affiliation, but there were no differences by sex (Fig. 1). The overall mean LDL was 112 ± 32 mg/dL, median HDL was 48 mg/dL (IQR: 40–57), and median triglycerides was 118 mg/dL (IQR: 88–157).

In the base model, Islamic religious affiliation (or those of Muslim faith) was associated with higher LDL, while no religious affiliation was associated with lower LDL (Table 2). In particular, Muslims had 9% (95% CI: 2 to 17%, p = 0.02) higher LDL compared to Hindus/Jains. Muslims also had lower HDL, while those with no religious affiliation had higher HDL. In particular, HDL was lower by 7% (95% CI: -12 to − 0.3%, p = 0.04) among Hindus/Jains, and by 9% (95% CI: -17 to − 1%, p = 0.03) among Muslims compared those with no religious affiliation. Muslims also had higher triglyceride levels; triglycerides were 20% (95% CI: 2 to 42%, p = 0.03) higher among Muslims compared to those with other religious affiliations, and 20% (95% CI: 3 to 41%, p = 0.02) higher compared to those with no religious affiliation.

Adjusting for all of the mediators concurrently for each outcome (LDL, HDL or triglycerides) had minimal effects on the adjusted means for each group (Table 2). Only two measures of mediation were nominally statistically significant: specifically, 60% (95% CI: 1 to 118%) of the difference in adjusted mean HDL between Muslims and those with no religious affiliation was explained by lifestyle behaviors, and in particular, alcohol intake explained 49% (95% CI: 0.4 to 97%).

Discussion

In a cross-sectional analysis of a community-based cohort of South Asians without known CVD, Muslims had higher LDL and triglyceride levels, and lower HDL levels, while participants with no religious affiliation had lower LDL levels and higher HDL levels. Hindus/Jains also had lower HDL levels compared to those with no religious affiliation. However, lifestyle behaviors did little to explain the associations between religious affiliation and cholesterol levels. The sole exception was the difference in HDL levels between Muslims and those with no religious affiliation, which was partly explained by lifestyle behaviors, in particular, by alcohol consumption.

While still controversial, reference standards for lipoprotein and lipid levels differ for South Asians compared to other ethnicities due to their markedly elevated risk for heart disease. For a person of average risk, an LDL level of ≤100 mg/dL, HDL level of ≥50 mg/dL for women and ≥ 40 mg/dL for men, and a triglyceride level of < 150 mg/dL [50, 51] are considered optimal. Age-, sex- and cholesterol medication use-adjusted mean LDL was slightly higher than the optimal range for all religious affiliations, the adjusted mean HDL was borderline, and the adjusted mean triglycerides was well below the optimal range in all groups. Thus, this study had a relatively healthy cohort with no major differences by religious affiliation.

While there is a paucity of studies on the relationship between religious affiliation and cholesterol levels in South Asian immigrants, our results are consistent with a previous study of South Asians in the U.K. that found lower HDL and higher triglycerides among Muslims compared to individuals of other religious affiliations [11]. Muslims are less likely to drink alcohol, and in our sample, majority of the Muslims did not consume alcohol. We found that moderate alcohol intake was associated with better lipid outcomes, specifically, higher HDL and lower triglyceride levels, independent of religious affiliation. Intervention studies in human subjects have shown ethanol-mediated HDL elevation, generally considered an important contributor to the beneficial and cardioprotective effects of moderate drinking [52,53,54]. However, socioeconomic status, physical activity, and diet also play a role [55]. Effects of alcohol consumption, moderate or otherwise, should be viewed as part of broader social, cultural, and lifestyle issues rather than in isolation [55, 56]. Cross-cultural prospective studies have shown that simply correlating the amount of alcohol consumed with CVD outcomes is inadequate as outcomes relate strongly to the patterns of drinking [55,56,57].

We examined physical activity and diet as other lifestyle behaviors that are influenced by religion. In general, South Asians have reportedly low rates of physical activity, and in our sample, one-third of participants were relatively sedentary (< 500 MET-min/week) [8, 58, 59]. Cultural, religious and gender norms have also been shown to be a barrier to physical activity among South Asian women [60]. Considerable evidence supports that physical activity and exercise have a positive impact on abnormal lipids [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. In our sample, Muslims had the most sedentary lifestyle while those with no religious affiliations had the most active lifestyle. Hindus/Jains were more active compared to Muslims. This could be a factor for the unfavorable cholesterol outcomes among Muslims compared to those with no religious affiliation, and may explain the higher LDL levels among Muslims compared to Hindus/Jains.

In addition to the sedentary lifestyle and innate genetic predisposition, the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and added sweeteners have been proven to specifically lower HDL [49, 58, 72], and diets rich in fruits and vegetables, low-fat dairy products, reduced saturated fat, total fat and cholesterol content have been proven to substantially lower the total and LDL-cholesterol concentration [73, 74]. In our sample, Hindus/Jains were more likely to consume fruits and vegetables diet but also sweets and refined grains. Thus, the beneficial effects of a healthy diet may have been masked resulting in lower HDL levels compared to those with no religious affiliation. Muslims were least likely to eat fruits and vegetables, thereby possibly contributing to some of the higher LDL and lower HDL levels among Muslims.

While smoking is considered an important conventional risk factor, a previous study found that the levels of smoking did not account for the high rates of CHD in South Asians, and measures to reduce the habit would only have a modest impact on total mortality in South Asians [75, 76]. Smoking did not mediate the association between religious affiliation and cholesterol levels in our current study, possibly due to the low rates of current smokers in this sample.

This study has limitations. Given the cross-sectional design, we are unable to draw causal inferences about the association between religious affiliation and cholesterol levels. Measures of religiosity, such as adherence to religious tenets or practices, were not measured, and may provide further explanation for the positive association; future questionnaires will include more detailed questions on religious participation. Dietary patterns may not have adequately captured the nuances between some religious groups [49]. For example, Muslims are more likely to eat meat and refrain from alcohol [49, 77] but majority of the Muslims were placed in the animal protein dietary pattern group, which included alcohol. The category “other” for religious affiliation may contain religions with contradictory dietary proscriptions. There may have been some loss of statistical power due to use of categorical predictors. While representative of the South Asian community in the U.S., majority of the sample was well educated, which may limit capturing the effect of socioeconomic status, and majority of the participants affiliated with Hinduism/Jainism, which resulted in unequal group sizes thereby causing further loss of statistical power [6]. Inflation of some of the fully adjusted coefficients relative to the base model suggests negative confounding. Bias may also arise from uncontrolled confounding of the association between the mediators and the outcomes.

The religious and cultural community are often synonymous for certain South Asian groups, and the social influences within these groups may encourage or discourage behaviors that influence CVD risk [17, 20, 78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Specifically in the U.S. where South Asians comprise 1.5% of the total population, we speculate that understanding different religious proscriptions would be clinically important for patient care. CVD outcomes are strongly associated with alcohol intake patterns, and drinking patterns are a result of the underlying social atmosphere. Although moderate drinking has been associated with better CVD outcomes, alcohol is prohibited for Muslims, and thus alternate modifications may be necessary. Based on our study, Muslims were least likely to eat fruits and vegetables, while Hindus ate greater amounts of sweets and refined grains. Thus, knowing this information with respect to diet and nutrition among different religious groups can help to tailor targeted interventions for patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that religion is associated with cholesterol levels in South Asians, and that some lifestyle behaviors may partially explain this risk. Specifically, the lack of alcohol consumption may contribute to lower HDL-cholesterol levels among Muslims. Behavioral lifestyle interventions to improve lipoprotein and lipid levels may be more effective if they take into account the influence of religious affiliation on lifestyle among the diverse South Asian population. Future interventional studies are required to confirm this association between South Asian religious groups, lifestyle behaviors and CVD risk.

Abbreviations

- CHD:

-

Coronary Heart Disease

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Disease

- HDL:

-

High-density Lipoprotein

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- LDL:

-

Low-density Lipoprotein

- MASALA:

-

Mediators in Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America

- MESA:

-

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- MET:

-

Metabolic Equivalent of Task

- PTE:

-

Proportion of total effect

- SDA:

-

Seventh-day Adventists

- SHARE:

-

Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic Groups

- U.K.:

-

United Kingdom

- U.S.:

-

United States

References

Jose PO, Frank ATH, Kapphahn KI, Goldstein BA, Eggleston K, Hastings KG, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23):2486–94.

Bilen O, Kamal A, Virani SS. Lipoprotein abnormalities in south Asians and its association with cardiovascular disease: current state and future directions. World J Cardiol. 2016;8(3):247–57.

Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V, Devanesen S, Teo KK, Montague PA, et al. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the study of health assessment and risk in ethnic groups (SHARE). Lancet. 2000;356(9226):279–84.

Misra A, Shrivastava U. Obesity and dyslipidemia in south Asians. Nutrients. 2013;5(7):2708–33.

Misra A, Luthra K, Vikram NK. Dyslipidemia in Asian Indians: determinants and significance. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:137–42.

Kanaya AM, Kandula N, Herrington D, Budoff MJ, Hulley S, Vittinghoff E, et al. Mediators of atherosclerosis in south Asians living in America (MASALA) study: objectives, methods, and cohort description. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(12):713–20.

Wulan SN, Westerterp KR, Plasqui G. Metabolic profile before and after short-term overfeeding with a high-fat diet: a comparison between south Asian and white men. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1853–61.

Vuksan V, Rogovik A, Jenkins A, Peeva V, Beljan-Zdravkovic U, Stavro M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors, diet and lifestyle among European, South Asian and Chinese adolescents in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17(1):e1–6.

Bakker LE, Boon MR, Annema W, Dikkers A, van Eyk HJ, Verhoeven A, et al. HDL functionality in south Asians as compared to white Caucasians. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26(8):697–705.

Tillin T, Hughes AD, Wang Q, Würtz P, Ala-Korpela M, Sattar N, et al. Diabetes risk and amino acid profiles: cross-sectional and prospective analyses of ethnicity, amino acids and diabetes in a south Asian and European cohort from the SABRE (Southall and Brent REvisited) study. Diabetologia. 2015;58:968–79.

McKeigue PM, Shah B, Marmot MG. Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk in south Asians. Lancet. 1991;337:382–6.

Gupta M, Brister S, Verma S. Is south Asian ethnicity an independent cardiovascular risk factor? Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(3):193–7.

Overview. Indian Heart Association. Web. http://indianheartassociation.org/why-indians-why-south-asians/overview/. Accessed 5 Mar 2017.

American Community Survey (ACS). US Census Bureau. Web. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/. Accessed 5 Mar 2017.

Mukherjea A, Underwood KC, Stewart AL, Ivey SL, Kanaya AM. Asian Indian views on diet and health in the United States: importance of understanding cultural and social factors to address disparities. Fam Community Health. 2013;36(4):311–23.

Radhika G, Sudha V, Sathya RM, Ganesan A, Mohan M. Association of fruit and vegetable intake with cardiovascular risk factors in urban south Indians. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:398–405.

Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: a focus on south Asians in Europe. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56:18891.

Basu-Zharku IO. “The Influence of Religion on Health.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse. 2011;3(01):1–3. Web. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=367.

Fekete EM, Williams SL. Chronic disease. In: Loue S, Sajatovic M, editors. Encyclopedia of immigrant health. New York: Springer Publishing; 2012.

Pollard TM, Carlin LE, Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M, Fischbacher C. Social networks and coronary heart disease risk factors in south Asians and Europeans in the UK. Ethn Health. 2003;8(3):263–75.

Basch L, Schiller NG, Blanc CS. Nations unbound: transnational projects. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach; 1994.

Kim I. The Koreans: small business in an urban frontier. In: Foner N, editor. New immigrants in New York. New York: Columbia University Press; 1987.

Zhou M. Chinatown: the socioeconomic potential of an urban enclave. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1992.

Schlundt DG, Franklin MD, Patel K, McClellan L, Larson C, Niebler S, et al. Religious affiliation and health behaviors and outcomes: data from the Nashville REACH 2010 project. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(6):714–24.

Kent LM, Morton DP, Ward EJ, Rankin PM, Ferret RB, Gobble J, et al. The influence of religious affiliation on participant responsiveness to the complete health improvement program (CHIP) lifestyle intervention. J Relig Health. 2016;55:1561–73.

Fraser GE. Diet, life expectancy, and chronic disease. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Nurdeng D. Lawful and unlawful foods in Islamic law focus on Islamic medical and ethical aspects. Int Food Res J. 2009;16:469–78.

Micha R, Michas G, Mozaffarian D. Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes – an updated review of the evidence. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14(6):515–24.

Goldstein P. Religion as a Social Determinant of Health in Muslim Countries: The Implementation of Positive Health Promotion. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection; 2016. p. 2354. http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2354

Aboul-Enein BH. Health-promoting verses as mentioned in the holy Quran. J Relig Health. 2014;55(3):821–9.

Scott G. The Ayurvedic guide to diet and weight loss: the sattva program. Wisconsin: Lotus Press; 2002.

Desai BP. Place of nutrition in yoga. Anc Sci Life. 1990;9(3):147–53.

Paul TR. Food yoga– nourishing body, mind & soul; 2012.

Priya G, Kalra S, Dardi IK, Saini S, Aggarwal S, Singh R, et al. Diabetes care: inspiration from Sikhism. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21(3):453–9.

Latt TS, Kalra S. Managing diabetes during fasting – a focus on Buddhist lent. Diabetes Voice. 2012;57:42–5.

Kalra S, Bajaj S, Gupta Y, Agarwal P, Singh SK, Julka S, et al. Fasts, feasts and festivals in diabetes-1: glycemic management during Hindu fasts. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:198–203.

Julka S, Sachan A, Bajaj S, Sahay R, Chawla R, Agrawal N, et al. Glycemic management during Jain fasts. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21:238–41.

Niazi AK, Kalra S. Patient centred care in diabetology: an Islamic perspective from South Asia. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2012;11:30.

Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S. The Indian diabetes prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia. 2006;49(2):289–99.

Isharwal S, Misra A, Wasir JS, Nigam P. Diet & insulin resistance: a review & Asian Indian perspective. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129(5):485–99.

Eliasi JR, Dwyer JT. Kosher and halal: religious observances affecting dietary intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(7):911–3.

Bharmal N, McCarthy WJ, Gadgil M, Kandula N, Kanaya AM. The Association of Religious Affiliation with overweight/obesity among south Asians: the mediators of atherosclerosis in south Asians living in America (MASALA) study. J Relig Health. 2018;57(1):33–46.

Jonnalagadda SS, Diwan S. Regional variations in dietary intake and body mass index of first-generation Asian-Indian immigrants in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(9):1286–9.

Raymond C, Sukhwant BAL. The drinking habits of Sikh, Hindu, Muslim and white men in the west midlands: a community survey. Addiction. 1990;85(6):759–69.

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–81.

Kelemen LE, Anand SS, Vuksan V, Yi Q, Teo KK, Devanesen S, et al. Development and evaluation of cultural food frequency questionnaires for south Asians, Chinese, and Europeans in North America. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(9):1178–84.

Wang ET, de Koning L, Kanaya AM. Higher protein intake is associated with diabetes risk in south Asian Indians: the metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis in south Asians living in America (MASALA) study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29(2):130–5.

Gadgil MD, Anderson CAM, Kandula NR, Kanaya AM. Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic risk factors in south Asians living in the United States. J Nutr. 2015;145(6):1211–7.

Cholesterol and South Asians. Indian Heart Association. Web. http://indianheartassociation.org/cholesterol-and-south-asians/. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

South Asians and Cholesterol. Palo Alto Medical Foundation - A Sutter Health Affiliate. 2008. Web. http://www.pamf.org/southasian/support/handouts/cholesterol.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar 2017.

Rimm EB, Williams P, Fosher K, Criqui M, Stampfer MJ. Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ. 1999;319:1523–8.

Leighton F, San Martin A, Castillo O, et al. Red wine, white wine and diet, intervention study: effect on cardiovascular risk factors. Proceedings of the XXV Congres Mondial de la Vigne et du Vin; 2000.

Hannuksela ML, Liisanantti MK, Savolainen MJ. Effect of Alcohol on Lipids and Lipoproteins in Relation to Atherosclerosis. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 2002;39(3):225–83.

The Harms and Benefits of Moderate Drinking. An international scientific conference, May 17–18, 2006, at The Inn at Harvard, Cambridge, MA. Sponsored by The Institute on Lifestyle & Health, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, and The International Center for Alcohol Policies, Washington, DC; 2006.

Evans A, Marques-Vidal P, Ducimetiere P, Montaye M, Arveiler D, Bingham A, et al. Patterns of alcohol consumption and cardiovascular risk in Northern Ireland and France. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(Suppl):S75–80.

Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, Arveiler D, Rajakangas AM, Pajak A. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA project: registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation. 1994;90:583–612.

Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, Dorairaj P, Kazmi K, et al. Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in south Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007;297(3):286–94.

2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Guidelines Index - 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008. Web. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/2008/.

Dave SS, Craft LL, Mehta P, Naval S, Kumar S, Kandula NR. Life Stage Influences on U.S. South Asian Women's Physical Activity. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(3):e100–8.

O'Keefe EL, DiNicolantonio JJ, Patil H, Helzberg JH, Lavie CJ. Lifestyle choices fuel epidemics of diabetes and cardiovascular disease among Asian Indians. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(5):505–13.

Trejo-Gutierrez JF, Fletcher G. Impact of exercise on blood lipids and lipoproteins. J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1:175–81.

Crichton GE, Alkerwi A. Physical activity, sedentary behavior time and lipid levels in the observation of cardiovascular risk factors in Luxembourg study. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:87.

Monda KL, Ballantyne CM, North KE. Longitudinal impact of physical activity on lipid profiles in middle-aged adults: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(8):1685–91.

Sternfeld B, Sidney S, Jacobs DR Jr, Sadler MC, Haskell WL, Schreiner PJ. Seven-year changes in physical fitness, physical activity, and lipid profile in the CARDIA study. Coronary artery risk development in young adults. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:25–33.

Young DR, Haskell WL, Jatulis DE, Fortmann SP. Associations between changes in physical activity and risk factors for coronary heart disease in a community-based sample of men and women: the Stanford five-city project. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:205–16.

Leon AS, Sanchez OA. Response of blood lipids to exercise training alone or combined with dietary intervention. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S502–15 (discussion S528–509).

Durstine JL, Grandjean PW, Cox CA, Thompson PD. Lipids, lipoproteins, and exercise. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 2002;22:385–98.

Tran ZV, Weltman A, Glass GV, Mood DP. The effects of exercise on blood lipids and lipoproteins: a meta-analysis of studies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1983;15:393–402.

Halbert JA, Silagy CA, Finucane P, Withers RT, Hamdorf PA. Exercise training and blood lipids in hyperlipidemic and normolipidemic adults: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:514–22.

Kodama S, Tanaka S, Saito K, Shu M, Sone Y, Onitake F, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise training on serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:999–1008.

Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):516–24.

Obarzanek E, Sacks FM, Vollmer WM, Bray GA, Miller ER 3rd, Lin PH, et al. DASH research group. Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure lowering diet: the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:80–9.

Fornes NS, Marins IS, Hernan M, Velasquez-Melendex G, Ascherio A. Frequency of food consumption and lipoprotein serum levels in the population of an urban area, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2000;34:380–7.

Konishi H, Miyauchi K, Kasai T, Tsuboi S, Ogita M, Naito R, et al. Long-term prognosis and clinical characteristics of young adults (≤40 years old) who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiol. 2014;64:171–4.

McKeigue PM, Miller GJ, Marmot MG. Coronary heart disease in south Asians overseas: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(7):597–609.

Fischer J. Religion, science and markets. Modern halal production, trade and consumption. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(9):828–31.

Akresh IR. Dietary assimilation and health among Hispanic immigrants to the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(4):404–17.

Batis C, Hernandez-Barrera L, Barquera S, Rivera JA, Popkin BM. Food acculturation drives dietary differences among Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and non-Hispanic whites. J Nutr. 2011;141(10):1898–906.

Guendelman MD, Cheryan S, Monin B. Fitting in but getting fat: identity threat and dietary choices among U.S. immigrant groups. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(7):959–67.

Kim MJ, Lee SJ, Ahn YH, Bowen P, Lee H. Dietary acculturation and diet quality of hypertensive Korean Americans. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(5):436–45.

Lv N, Cason KL. Dietary pattern change and acculturation of Chinese Americans in Pennsylvania. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(5):771–8.

Raj S, Ganganna P, Bowering J. Dietary habits of Asian Indians in relation to length of residence in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;9:1106–8.

Karim N, Bloch DS, Falciglia G, Murthy L. Modifications in food consumption patterns reported by people from India, living in Cincinnati, Ohio. Ecol Food Nutr. 1986;19(1):11–8.

Garduno-Diaz SD, Khokhar S. South Asian dietary patterns and their association with risk factors for the metabolic syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26(2):145–55.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the MASALA participants and the field staff and interns at the UCSF and Northwestern clinical centers.

Funding

The MASALA study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant 1R01HL093009 and 1R01HL120725. Data collection at UCSF was supported by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131. The funding body played no role in the design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GH implemented the methods, conducted statistical analysis, and prepared the manuscript. EV conducted statistical analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. NB developed the protocol. NK supervised data collection, and reviewed the manuscript. AK obtained funding, supervised data collection, supervised the conduct of statistical analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have reviewed the submitted manuscript and approve the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The UCSF and NWU institutional review boards approved the protocol.

Research involving human participants: Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirode, G., Vittinghoff, E., Bharmal, N.H. et al. The association of religious affiliation with cholesterol levels among South Asians: the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 19, 75 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1045-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1045-z