Abstract

Background

Recently, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has become the procedure of choice in high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (AS). However, its value is still debated in operable AS cases. We performed this meta-analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of TAVR to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in low-to-moderate surgical risk patients with AS.

Methods

A systematic search of five authentic databases retrieved 11 eligible studies (20,056 patients). Relevant Data were pooled as risk ratios (RRs) or standardized mean differences (SMD), with their 95% confidence interval, using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis and RevMan software for windows.

Results

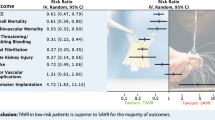

At one-year of follow-up, the pooled effect-estimates showed no significant difference between TAVR and SAVR groups in terms of all-cause mortality (RR 1.02, 95% CI [0.83, 1.26], stroke (RR 0.83, 95%CI [0.56, 1.21]), myocardial infarction (RR 0.82, 95% CI [0.57, 1.19]), and length of hospital stay (SMD -0.04, 95% CI [−0.34, 0.26]). The incidence of major bleeding (RR 0.45, 95% CI [0.24, 0.86]) and acute kidney injury (RR 0.52, 95% CI [0.30, 0.88]) was significantly lower in the TAVR group, compared to the SAVR group. However, TAVR was associated with a higher risk of permanent pacemaker implantation (RR 2.57, 95% CI [1.36, 4.86]), vascular-access complications at 1 year (RR 1.99, 95%CI [1.04, 3.80]), and paravalvular aortic regurgitation at 30 days (RR 3.90, 95% CI [1.25, 12.12]), compared to SAVR.

Conclusions

Due to the comparable mortality rates in SAVR and TAVR groups and the lower risk of life-threatening complications in the TAVR group, TAVR can be an acceptable alternative to SAVR in low-to-moderate risk patients with AS. However, larger trials with longer follow-up periods are required to compare the long-term outcomes of both techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most prevalent valvular heart disease in the elderly [1]. An epidemiological study estimated that more than one in eight individuals over the age of 75 years has a moderate to severe AS [2]. Another meta-analysis revealed that the pooled prevalence of the disease among the elderly is 12.4% and estimated that there are more than 291,000 candidates for aortic valve replacement in North America and Europe [3].

Although surgery is still considered the intervention of choice in operable cases of severe AS, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is continuously gaining ground in these lower risk groups [4]. This growing trend is justified by multiple reasons including the remarkable technical advances in the valve replacement procedure which now allows for easy repositioning and removal, the minimally invasive approach that permits performing under local anesthesia [5], as well as the fact that TAVR is a common patient preference among surgically fit cases due to its shorter hospital stay, lower risk of bleeding and mild post-interventional symptoms [6].

Nevertheless, the increasing TAVR drift towards lower surgical risk strata lacks a solid ground of evidence and does not adhere to the well-established guidelines [7]. In fact, only four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressed this issue including the PARTNER-II, US pivotal, NOTION, and the prematurely-terminated STACATTO trial [8,9,10,11]. Given this paucity of RCTs, observational studies are rendered a legitimate strategy to assess the comparative effectiveness of both procedures in operable patients [12].

We aimed to synthesize level I evidence from published randomized trials and observational studies as to whether or not TAVR could be compared to surgery in terms of efficacy and safety outcomes in low-to-moderate surgical risk patients with AS.

Methods

We performed this meta-analysis in accordance to the guidelines of the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [13] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA statement guidelines) [14].

Literature search strategy

We performed a comprehensive search of five authentic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of science, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)) using the following strategy: [Aortic Stenosis OR Aortic Valve Stenosis OR Aortic Valve Replacement OR Aortic Valve Implantation OR Heart Valve Replacement AND Transcatheter OR TAVR OR Transfemoral OR Transapical AND Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement OR SAVR OR Surgical AVR AND Low Risk OR Moderate Risk OR Intermediate Risk]. There was no restriction by the language of the study or year of publication. We screened the bibliography of eligible articles for any relevant studies and the clinical trial registry (Clinicaltrials.gov) for any ongoing or unpublished studies.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

We included both RCTs and non-randomized studies (prospective and retrospective observational studies) if they matched the following criteria: (1) Population: Patients with severe AS and a low-to-moderate surgical risk [defined as a logistic Euroscore for cardiac operative risk evaluation (≤ 20%) or a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score below 8%], (2) Intervention: Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR: through all routes including transfemoral, transapical, and transaxillary routes), (3) Comparator: Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR), and (4) Outcomes: Studies that at least included one efficacy (mortality) or safety outcome.

We excluded case reports, case series, and studies that exclusively enrolled patients with high surgical risk. Eligibility screening was conducted in a two step-wise manner (title/abstract screening and full-text screening). Each step was conducted by three reviewers and consensus was obtained upon consulting a fourth reviewer (Abushouk AI).

Data extraction

Three independent authors extracted the relevant data and another reviewer (Elmaraezy A) resolved disagreements. The extracted data included (1) Study year and design, (2) Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients, and (3) Outcomes including the length of hospital stay and the incidence of all-Cause mortality (efficacy outcome), major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MAACE), stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), major life-threatening bleeding, acute kidney injury (AKI), vascular access complications (VAC), paravalvular aortic regurgitation (AR), and permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI).

Risk of bias assessment

Three independent reviewers used the Cochrane risk of bias tool, clearly described in (chapter 8.5) of the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 5.1.0 [13], to assess the risk of bias within included RCTs. For cohort and case-control studies, we used the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) for detection of bias in non-randomized studies [15]. This tool assesses the risk of bias in observational studies based on reporting of three important domains: selection of the study subjects, comparability of groups regarding demographic characteristics and important potential confounders, and ascertainment of the prespecified outcome. Whenever an outcome included 10 or more studies, we assessed for publication bias, using the Egger’s test [16].

Data synthesis

Dichotomous data for efficacy and safety outcomes were pooled as risk ratios (RRs), using the Mantel-Haenszel method. Data for hospital stay duration were pooled as a standardized mean difference (SMD), using the Inverse Variance (I-V) method. All statistical analyses in this study were performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Biostat Inc) and RevMan (version 5.3) software for windows. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi-Square test and its extent was measured using the I-Square test. When a significant heterogeneity was found, the analysis was conducted under the random-effects model. In each included outcome, we performed a subgroup analysis by the endpoint of assessment (30 days, 1, 2, or 3 years after the procedure).

Results

Literature search results

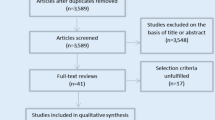

Our literature search retrieved 4587 studies. Of them, 27 full text articles were assessed for eligibility. Finally, 11 studies (reported in 15 published articles) [7,8,9,10,11,12, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] were included in this meta-analysis [20,056 Patients]. The flow of study selection is shown in our PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). Four eligible studies were RCTs, while the remaining seven studies included five prospective cohort and two retrospective studies. The summary of included studies and baseline characteristics of enrolled patients are shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included RCTs ranged from low to moderate as assessed by the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Authors’ judgements on the risk of bias in included RCTs are illustrated in Additional file 1. The risk of bias in included observational studies was low as assessed by the Newcastle Ottawa scale (mean = 8 out of 9 asterisks).

Safety and efficacy outcomes

All-cause mortality

The overall RR did not favor either of the two groups in terms of in-hospital mortality (RR 1.11, 95% CI [0.63 to 1.95]), 30-day morality (RR 0.95, 95% CI [0.74 to 1.21]), 1-year mortality (RR 1.02, 95% CI [0.83 to 1.26]), or 2-year mortality (RR 0.91, 95% CI [0.76 to 1.08]). These findings were consistent with another scenario in which we considered pooling of data from RCTs only. The RR of 3-year mortality was reported only by the OBSERVENT study, which showed a significantly higher risk of mortality in the TAVR group than the SAVR group (RR 1.63, 95% CI [1.21 to 2.19]) (Fig. 2).

MACCE

The pooled analysis of two RCTs, reporting 1- and 2-year MACCE, favored the TAVR group over the SAVR group (1-year MACCE: RR 0.77, 95% CI [0.61 to 0.98]; and 2-year MACCE: RR 0.79, 95% CI [0.65 to 0.95]). The 30-day MACCE was reported by the US pivotal study only, which showed comparable rates of MACCE between the two groups (RR 0.74, 95% CI [0.47 to 1.18]). Similarly, the 3-year MACCE was reported only by the OBSERVENT study, which favored the SAVR over TAVR (RR 1.70, 95% CI [1.31 to 2.21]) in this regard (Fig. 3).

Stroke

The overall RR did not favor either of the two groups in terms of stroke incidence within 30 days (RR 0.99, 95% CI [0.73 to 1.35]), 1 year (RR 0.83, 95% CI [0.56 to 1.21]), or 2 years (RR 0.88, 95% CI [0.63 to 1.23]) after the procedure. The OBSERVENT study reported a higher 3-year risk of stroke in the TAVR group (RR 2.54, 95% CI [1.36 to 4.74]), compared to SAVR group. For the risk of stroke at 30 days, there was no evidence of publication bias (p = 0.66) (Fig. 4).

Myocardial infarction

The overall RR did not favor either of the two groups in terms of myocardial infarction rate within 30 days (RR 0.64, 95% CI [0.39 to 1.04]), 1 year (RR 0.82, 95% CI [0.57 to 1.19]), 2 years (RR 0.96, 95% CI [0.52 to 1.76]), or 3 years (RR 1.20, 95% CI [0.37 to 3.90]). These findings were consistent when we considered pooling data from RCTs only.

Major life threatening bleeding

The RR of major bleeding was heterogeneous across studies for 30-day and 1- and 2-year endpoints (I2 = 96%, I2 = 97%, and I2 = 97%, respectively). Out of the 9 studies reporting the risk of major bleeding, seven studies (n = 4864 patients) reported a lower incidence of major bleeding in the TAVR group compared with the SAVR group. The STACCATO study showed comparable risk of bleeding between the two groups (1/34 vs. 1/36, respectively), while the ninth study (OBSERVENT) showed a relatively higher incidence of major bleeding in the TAVR group than the SAVR group. When considering data from RCTs only, the pooled RR supported that TAVR has a significantly lower risk of major bleeding than SAVR after 30 days (RR 0.44, 95% CI [0.22 to 0.92]), 1 year (RR 0.45, 95% CI [0.24 to 0.86]), and 2 years (RR 0.48, 95% CI [0.27 to 0.88]).

Acute kidney injury

The overall RR of AKI was lower in the TAVR group than the SAVR group at the endpoints of 30 days (RR 0.45, 95% CI [0.34 to 0.59]), 1 year (RR 0.52, 95% CI [0.30 to 0.88]), and 2 years (RR 0.52, 95% CI [0.33 to 0.80]). These findings were consistent with the other scenario in which we considered pooling of data from RCTs only.

Vascular access complications

The overall RR showed a higher risk of VAC in the TAVR group compared to the SAVR group at the endpoints of 30 days (RR 12.38, 95% CI [2.46 to 62.28]), 1 year (RR 1.99, 95% CI [1.04 to 3.80]), and 2 years (RR 2.16, 95% CI [1.00 to 4.67]). These findings were consistent when we considered pooling data from RCTs only.

Paravalvular aortic regurgitation

The RR of paravalvular AR at 30 days showed a higher incidence of AR in the TAVR group than the SAVR group (RR 3.90, 95% CI [1.25 to 12.12]). Similar results were obtained when pooling data of RCTs only with stratification of AR into mild vs. moderate/severe. The subtotal effect estimates were as follows: (Mild AR: RR 10.21, 95% CI [5.76 to 18.09]; and Moderate/Severe AR: RR 9.30, 95% CI [3.14 to 27.58]).

Permanent pacemaker implantation

Compared to SAVR, the risk of PPI was higher in the TAVR group at 30 days (RR 3.31, 95% CI [2.05 to 5.35]), 1 year (RR 2.57, 95% CI [1.36 to 4.86]), but not after 2 years (RR 1.57, 95% CI [0.91 to 2.70]), probably due to the small number of included studies at the 2-year endpoint. When analyzing data from RCTs only, the effect estimate favored the SAVR group over the TAVR group at all endpoints (30-day and one- and two-years).

Hospital stay

Six studies reported the duration of hospital stay. Of them, 4 studies showed significantly less hospital stay after TAVR, compared to SAVR. However, the fifth study showed the reverse and the sixth study did not favor either of the two groups. The pooled effect size of hospital stay did not favor either of the two groups (SMD -0.04, 95% CI [−0.34 to 0.26]). However, as we mentioned, this effect size was heterogeneous (I2 = 95%).

Discussion

Since its introduction in 2002, TAVR has attracted the interest of interventional cardiologists as a possible alternative to SAVR [26]. Recently, the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American College of Cardiology /American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommended TAVR as the procedure of choice in high surgical risk patients [27, 28]. However, its value is still debated in AS patients with a low-to-moderate surgical risk. Recently, the ACC added TAVR as a grade IIa recommendation in AS patients with an intermediate surgical risk [29].

Our analysis of data from over 20,000 low-to-moderate risk patients showed no significant difference between SAVR and TAVR in terms of the incidence of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, and MACCE, as well as the length of hospital stay. A higher risk of life-threatening bleeding and AKI was detected in the SAVR group, while the TAVR procedure was associated with a higher risk of VAC and paravalvular AR.

The increased risk of paravalvular AR with TAVR was noted in most included studies, as well as our meta-analysis. This finding can be attributed to multiple valvular and procedural factors, including native valve calcification, the angle of the left ventricle outflow tract to the proximal ascending aorta, inadequate balloon expansion, mismatch between the size of the aortic annulus and the TAVR device, and inadequate deployment technique [30]. However, the procedural limitations are expected to improve with the introduction of newer generation devices and increased TAVR experience among interventional practitioners [31]. Of note, several included trials used the 2-Dimensional echocardiography for valve sizing, which has been shown to cause systematic valve undersizing, leading to a higher incidence of AR, compared to multislice computed tomography (MSCT) [32]. Using MSCT to measure the valve size and the degree of native valve complications can reduce the risk of annulus rupture, coronary artery obstruction, and conduction abnormalities [33, 34].

In the 10 studies that compared both procedures regarding the incidence of stroke, neurological examination was clinically-based and imaging was only requested in patients with evident neurological manifestations. Because the main nuerological outcome was the occurrence of stroke, these studies did not assess for more subtle neurological sypmtoms. In a study by Rodes-Cabau et al., cerebral defects were detected in 70% of patients post-TAVR on magnetic resonance imaging [35]. Future studies should consider incorporating cognitive tests and neuroimaging techniques in their regular neurological evaluations.

As expected, our analysis showed a higher incidence of VAC in the TAVR group, compared to the SAVR group. This finding is commonly explained by the percutaneous nature of the procedure and using large-bore introducer sheaths. In a study by Mussardo et al. [36], a 60% reduction in the incidence of VAC was recorded following the introduction of catheter systems with smaller sheaths, such as the SAPIEN XT and the CoreValve systems. The vascular complications are expected to decrease with the continous improvement of catheter systems.

Although not assessed in this analysis, the PARTNER II trial [8] and SAPIEN III study [37] compared the echocardiographic findings in patients who underwent surgery or transcatheter replacement after 30 days of the procedure. These studies showed that both procedures significantly increased the left ventricular ejection fraction and decreased the mean aortic-valve gradients; however, the improvement was greater in the TAVR group at all time endpoints (up to 2 years following the procedure).

All included studies consistently used the logistic EuroSCORE or the STS risk models for operative risk calculation. However, these score are currently considered outdated and may overestimate the true individual risk [38]. Moreover, it does not consider several elderly-related risk factors, such as fraility, porcelain aorta, malnutrition, and chest deformities [39]. The transcatheter approach may be a better alternative for these patients because they may not be surgical candidates. However, this needs confirmation in future RCTs.

Our results are in accordance with a former meta-analysis of five clinical studies (3199 patients) by Kondur et al. [31]. However, they showed a comparable rate of AKI between both procedures. These differences can be attributed to the marked difference in study inclusion criteria. We believe our results are more credible because they are based on pooling a higher number of clinical trials, as well as observational studies. The low risk of bias in the majority of included studies adds to the credibility of our evidence. Additionally, we performed a subgroup analysis according to the time endpoint at which the outcome was measured (Up to 3 years).

Despite these strength points, our analysis is not without limitations. Observational studies are prone to the effect of unmeasured confounders, which may influence the accuracy of our results. Moreover, meta-analysis of relatively rare events, such as myocardial infarction after these procedures, has its limitations because the occurrence of few events can change the summary effect estimate [40]. Only one study (OBSERVENT) compared both techniques in terms of mortality rate at 3 years and showed a higher risk in the TAVR group; however, more data are needed to confirm this finding.

Future trials are advised to compare the durability of the implanted valves and surgical bioprostheses. Longer follow up periods would be of value because TAVR is likely to expand to younger patients with lower mortality risks. Osnabrugge et al. (2012) compared SAVR and TAVR techniques in terms of the procedural time and costs. Their analysis found a shorter procedural time and a higher cost in the TAVR group, compared to the SAVR group, mostly due to the use of more expensive TAVR devices. These costs were not compensated by the shorter hospital stay and reduced need for blood transfusion in the TAVR group according to their analysis [21].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study shows comparable rates of mortality, stroke, and myocardial infarction between SAVR and TAVR groups and a lower risk of life-threatening complications (major bleeding and AKI) in the TAVR group. Although the risks of paravalvular AR and VAC were higher in the TAVR group, these complications are expected to decrease with the continous improvement of catheter systems and TAVR experience among interventional cardiologists. Therefore, TAVR can be an acceptable alternative to SAVR in low-to-moderate risk patients with AS. Larger trials with longer follow-up periods are required to compare the long-term outcomes of both techniques.

Abbreviations

- AR:

-

Aortic regurgitation

- AS:

-

Aortic stenosis

- MAACE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

- SAVR:

-

Surgical aortic valve replacement

- TAVR:

-

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

References

Lindroos M, Kupari M, Heikkilä J, Tilvis R. Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: an echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:1220–5.

Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005–11.

Osnabrugge RLJ, Mylotte D, Head SJ, et al. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1002–12.

Cribier A, Durand E, Eltchaninoff H. Patient selection for TAVI in 2014: is it justified to treat low-or intermediate-risk patients? The cardiologist’s view. EuroIntervention: journal of EuroPCR in collaboration with the Working Group on Interventional Cardiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2014;10:U16–21.

Oguri A, Yamamoto M, Mouillet G, et al. Clinical outcomes and safety of transfemoral aortic valve implantation under general versus local anesthesia. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2014;7:602–10.

Rees CM, Eric HO. Should patients with low-moderate surgical risk be offered TAVI instead of conventional aortic valve replacement in the management of symptomatic aortic stenosis? Res Medica. 2015;23:15–21.

Tamburino C, Barbanti M, D’Errigo P, et al. 1-year outcomes after transfemoral transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement: results from the Italian OBSERVANT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:804–12.

Martin B. Leon, M.D. CR et cols (2016) Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med 374:1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616.

Thyregod HGH, Steinbrüchel DA, Ihlemann N, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis: 1-year results from the all-comers NOTION randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2184–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.014.

Reardon MJ, Adams DH, Kleiman NS, et al. 2-Year Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Surgical or Self-Expanding Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.017.

Nielsen HH, Klaaborg KE, Nissen H, et al. A prospective, randomised trial of transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs. surgical aortic valve replacement in operable elderly patients with aortic stenosis: the STACCATO trial. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:383–9. doi: 10.4244/eijv8i3a58.

D’Errigo P, Barbanti M, Ranucci M, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis: results from an intermediate risk propensity-matched population of the Italian OBSERVANT study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1945–52.

Higgins JP, Green S (2008) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. doi: 10.1002/9780470712184.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400590.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1997;315:629–34.

Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Prosthesis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1790–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400590.

Castrodeza J, Amat-Santos IJ, Blanco M, et al. Propensity score matched comparison of transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus conventional surgery in intermediate and low risk aortic stenosis patients: A hint of real-world. Cardiology Journal. 2016;23:541–51. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2016.0051.

Latib A, Maisano F, Bertoldi L, et al. Transcatheter vs surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate- surgical-risk patients with aortic stenosis: A propensity score-matched case-control study. Am Heart J. 2012;164:910–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.09.005.

Möllmann H, Bestehorn K, Bestehorn M, et al. In-hospital outcome of transcatheter vs. surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic valve stenosis: complete dataset of patients treated in 2013 in Germany. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016;105:553–9. doi: 10.1007/s00392-016-0962-4.

Osnabrugge RLJ, Head SJ, Genders TSS, et al. Costs of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1954–60. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.07.002.

Piazza N, Kalesan B, Van Mieghem N, et al. A 3-center comparison of 1-year mortality outcomes between transcatheter aortic valve implantation and surgical aortic valve replacement on the basis of propensity score matching among intermediate-risk surgical patients. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2013;6:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.01.136.

Rosato S, Santini F, Barbanti M, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation compared with surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2016;9:e003326. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003326.

Schymik G, Heimeshoff M, Bramlage P, et al. A comparison of transcatheter aortic valve implantation and surgical aortic valve replacement in 1,141 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis and less than high risk. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:738–44. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25866.

Søndergaard L, Steinbrüchel DA, Ihlemann N, et al. Two-Year Outcomes in Patients With Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis Randomized to Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2016;9(6):e003665.

Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2002;106:3006–8.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al (2014) 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 129:CIR. 0000000000000031.

Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). G Ital Cardiol (2006). 2013;14:167–214.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al (2017) 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology CIR.0000000000000503.

Détaint D, Lepage L, Himbert D, et al. Determinants of significant paravalvular regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: impact of device and annulus discongruence. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2009;2:821–7.

Kondur A, Briasoulis A, Palla M, et al. Meta-analysis of transcatheter aortic valve replacement versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:252–7.

Mylotte D, Dorfmeister M, Elhmidi Y, et al. Erroneous measurement of the aortic annular diameter using 2-dimensional echocardiography resulting in inappropriate CoreValve size selection: a retrospective comparison with multislice computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2014;7:652–61.

Leipsic J, Gurvitch R, LaBounty TM, et al. Multidetector computed tomography in transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2011;4:416–29.

Achenbach S, Delgado V, Hausleiter J, et al. SCCT expert consensus document on computed tomography imaging before transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)/transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Journal of cardiovascular computed tomography. 2012;6:366–80.

Rodés-Cabau J, Dumont E, Boone RH, et al. Cerebral embolism following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: comparison of transfemoral and transapical approaches. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:18–28.

Mussardo M, Latib A, Chieffo A, et al. Periprocedural and short-term outcomes of transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the Sapien XT as compared with the Edwards Sapien valve. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2011;4:743–50.

Thourani VH, Kodali S, Makkar RR, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement versus surgical valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients: a propensity score analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:2218–25.

Osswald BR, Gegouskov V, Badowski-Zyla D, et al. Overestimation of aortic valve replacement risk by EuroSCORE: implications for percutaneous valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2008;30:74–80.

Wendt D, Osswald BR, Kayser K, et al. Society of Thoracic Surgeons score is superior to the EuroSCORE determining mortality in high risk patients undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:468–75.

Shuster JJ, Jones LS, Salmon DA. Fixed vs random effects meta-analysis in rare event studies: The Rosiglitazone link with myocardial infarction and cardiac death. Stat Med. 2007;26:4375–85.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All supplementary data on which our conclusion relies are available as supplementary files with the main manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AE: Participated in idea conception, literature search, screening records and writing. AI: Participated in screening records, data extraction and writing. AIA: Participated in data extraction, risk of bias assessment and writing. ME: Participated in data extraction, risk of bias assessment and writing. SS: Participated in data extraction and preparing supporting Tables AN: Participated in data extraction and manuscript writing. OMA: Participated in risk of bias assessment and writing. ARA: Participated in screening records and preparing supporting tables. AMAF: Participated in data extraction and preparing supporting tables. HMH: Participated in screening records and risk of bias assessment AGE: Participated in data extraction and preparing supporting Tables. MM: Participated in risk of bias assessment and writing. FA: Participated in data extraction and drafting the manuscript. MA: Participated in screening records and data analysis. AMA: Participated in data analysis and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

shows risk of bias (ROB) assessment results for included randomized trials and observational studies, according to Cochrane ROB tool and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. (DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Elmaraezy, A., Ismail, A., Abushouk, A.I. et al. Efficacy and safety of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in aortic stenosis patients at low to moderate surgical risk: a comprehensive meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17, 234 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0668-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0668-1