Abstract

Background

Since their discovery, vacuolar processing enzymes (VPEs) have consistently been investigated as programmed cell death (PCD) initiators and participants in plant development and responses to biotic or abiotic stresses, in part due to similarities with the apoptosis regulator caspase-1. However, recent studies show additional functions of VPE in tomatoes, specifically in sucrose accumulation and fruit ripening.

Results

Herein, we evaluated the functions of VPE from sweetpotato, initially in expression pattern analyses of IbVPE1 during development and senescence. Subsequently, we identified physiological functions by overexpressing IbVPE1 in Arabidopsis thaliana, and showed reduced leaf sizes and numbers and early flowering, and elucidated the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Conclusions

The present data demonstrate functions of the VPE gene family in development and senescence and in regulation of flowering times, leaf sizes and numbers, and senescence phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Leaf development is controlled by complex networks of hormones, enzymes, transcription factors, and microRNA. Over the life cycles of leaves, these factors contribute to the formation of leaf shapes and control leaf sizes. These and other leaf features vary widely among species, and differences within the same plant reflect multiple developmental stages and diverse environmental conditions, and the regulatory actions of endogenous hormones and transcription factors. In Arabidopsis plants, the plant-specific transcription factor teosinite branched1/cycloidea/pcf (TCP) has been implicated in the control of cell proliferation and differentiation, and in the regulation of leaf development [1]. The subsequent stage is known as the floral transition, and is regulated by multiple pathways that can be affected by environmental and endogenous factors [2]. Many flowering-related genes have been identified in Arabidopsis plants, including LFY, AP1, SOC1, CO, FT, FRI, FLC, BN1, BN2, FPA, FVE, FCA, and LD. These genes regulate flowering by either controlling hormones or by directly influencing the formation of floral organs.

Plant senescence is a major and essential process for plant development, and leaf senescence is a visible indictor of plant aging. The related cessation of photosynthesis and degradation of chlorophyll are regulated by many external and endogenous factors, including environmental cues, hormones, ROS, transcription factors, and nutrient deficiencies [3, 4]. Chl breakdown is a visual feature of leaf senescence, and leads to loss of green color and carotenoid or anthocyanin accumulation [5, 6]. Recently, the Chl catabolism pathway has been well-characterized in higher plants, and the ensuing genes in Arabidopsis include CLH, PAO, RCCR, PPH, SGR, and NYC, which all encode key enzymes of Chl catabolism.

Vacuolar processing enzymes (VPEs) are cysteine proteinases with functions in the processing of vacuolar proteins and the maturation of seed storage proteins [7,8,9,10,11]. Since the discovery of VPE and its proteolytic activity toward synthetic caspase-1 substrates, VPE functions have been linked to developmental and stress-induced programmed cell death (PCD) [12]. In Arabidopsis plants, VPE are expressed in all tissues [13, 14] and genes encoding VPE proteins have been classified as vegetative type proteins such as αVPE and γVPE [15] and βVPE in embryos and seeds [16], and δVPE, which is specifically and transiently expressed in the two cell layers of the seed coat during the earliest stage of seed development [17]. VPEs play essential roles in plant developmental and senescence–PCD, and in the accumulation of storage proteins [18]. Numerous studies of vegetative VPEs have defined functions under abiotic or biotic stress conditions, such as salt, wounding, pathogen infection, treatments with hormones such as jasmonic acid [14, 19], and in cell death caused by senescence [11] or disease [20, 21]. VPEs are reported to be up-regulated during petal and leaf senescence, indicating the potential role in plant senescence [19]. Silencing of vegetative type VPEs (NtVPE1) represses TMV-meditated hypersensitive cell death [21], and in Arabidopsis plants, VPE is reportedly involved in both fumonisin-induced cell death and developmental cell death of seed integuments [17]. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that VPEs are essential for various types of cell death during plant development and senescence, and in response to various stresses.

Numerous studies of VPEs reveal functions in PCD-related biological processes, including those related to development and stress responses. However, little is known about PCD-unrelated functions of VPE during plant growth. In the present study, we elucidated previously unknown roles of VPEs in plant development and senescence. Specifically, our data demonstrate that IbVPE1 affects plant development and senescence by regulating TCP transcription factors and genes of AP1 and Chl catabolism pathways.

Results

Identification and expression patterns of IbVPE1 in sweetpotato

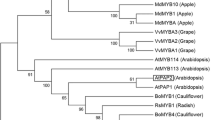

To determine roles of VPEs in sweetpotato, we identified and analyzed the functions of the IbVPE1 gene by screening the Xu18 fosmid library that was constructed by the key lab of plant integrity, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, Jiangsu. After sequencing and sequence alignment analyses, full-length cDNA and genomic DNA of IbVPE1 were identified. Comparisons of cDNA and genomic DNA revealed that IbVPE1 contains nine exons and eight introns (Fig. 1a) and encodes a peptide of 492 amino acids. Moreover, the essential amino acids for catalytic activity and the substrate binding pocket were determined according to caspase-1 activity (Fig. 1b) [13, 22, 23]. Subsequently, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using MEGA 5.0 software and showed that the closet AtVPE to IbVPE1 is gama-AtVPE, suggesting that it can be classified into the vegetative type of gama-AtVPE (Fig. 1c).

Analyses of sequences, phylogenetics, and tissue-specific expression patterns of IbVPE1; a IbVPE1 gene structure including the genomic sequence and full-length cDNA; yellow boxes indicate exons and blue lines indicate introns. b IbVPE1 amino acid sequence; gray boxes indicate essential amino acids for caspase-1 like activity. c the phylogenetic tree of IbVPE1 was constructed from alignments with VPE proteins from other species using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 5.0 software. d Tissue-specific expression pattern of IbVPE1 in sweetpotato; IbTublin was used as an internal control

To analyze expression patterns of IbVPE1 in sweetpotato, we examined transcription levels in various tissues and development stages using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and related gene expression analyses to morphologies of sweetpotato leaves (Fig. 2a). These analyses revealed that IbVPE1 is expressed in all tissues (Fig. 2b). However, IbVPE1 expression during leaf and root development and leaf senescence was 10–40 and 30–90 fold higher than in matured leaves and roots, respectively (Fig. 2c). These results suggest that sweetpotato IbVPE1 is strongly transcribed during leaf and root development and during leaf senescence.

Leaf morphology and IbVPE1 expression patterns across developmental stages of leaves and roots of sweetpotato; a the morphologies of sweetpotato leaves; b expression levels of IbVPE1 during five developmental stages of sweetpotato leaves; c expression level of IbVPE1 during five developmental stages in sweetpotato roots; IbTublin was used as an internal control. One-way ANOVA was used to data anaylsis

Localization and expression pattern of IbVPE1 in transgenic plant

To study the functions of IbVPE1, we generated IbVPE1 overexpressing Arabidopsis plants. RT-PCR analysis of homozygous T3 transgenic seedlings confirmed strong expression of IbVPE1 in OX-1, OX-2, and OX-3 mutant seedlings compared with WT seedlings (Fig. 3a).

RT-PCR analysis, subcellular localization, and expression patterns of IbVPE1; a quantitative RT-PCR analyses of IbVPE1 expression in wild-type (WT) and overexpressing (OX) plants; AtTublin was used as an internal control; b Subcellular localization of IbVPE1 in fluorescent microscopy analyses; c IbVPE1 expression levels in the five developmental stages of Arabidopsis leaves; d IbVPE1 expression across the five developmental stages of Arabidopsis roots; AtTublin was used as an internal control. One-way ANOVA was used to data anaylsis

To confirm the subcellular localization of IbVPE1, full-length cDNA was fused to GFP under the control of the 35S promoter (Fig. 3b). Subsequently, we used an GFP empty vector as a negative control and stained the onion vacuolar with neutral red dye as a positive control and observed similar vacuolar localization to positive control in onion epidermis cell by fluorescence microscope.

To investigate expression patterns of IbVPE1 in transgenic plants, we determined transcription levels in various tissues and development stages (Fig. 3c-d) by expression of IbVPE1-promoter-driven GUS construct in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. These experiments showed similar expression patterns to those observed in sweetpotato, including strong expression in developing and aging leaves, compared with matured leaves (30 days old leaves). However, IbVPE1 expression levels did not change significantly during root development, suggesting an important role of IbVPE1 during sweetpotato root tube development.

IbVPE1 affects leaf development and flowering times by regulating several TCP transcript factors and AP1

Under long-day conditions, leaf shapes of OX strains differed from those of WT plants at the bolting stage (Fig. 4a). Moreover, quantitative analyses of leaf traits showed that lengths of petioles in OX plants were similar to those in wide type plants (Additional file 1: Figure S4a), whereas OX plants had decreased blade lengths (Additional file 1: Figure S4b), blade widths (Additional file 1: Figure S4c), blade perimeters (Additional file 1: Figure S4d), and blade areas (Additional file 1: Figure S4e) compared their wild-type counterparts, and flowered comparatively early (Fig. 4b). In measurements of plant ages and rosette leaf numbers at the time of bolting, OX plants flowered an average of 5 days earlier than WT plants (Additional file 1: Figure S4f) and average numbers of rosette leaves were significantly lower than in WT plants (Additional file 1: Figure S4 g). These results suggest that IbVPE1 affects leaf development and accelerates flowering.

Phenotype analysis of IbVPE1 in WT and OX plants; a leaf shapes and numbers in WT and OX plants at the bolting stage; b flowering times in WT and OX plants. The quantitative data of petiole length, blade length, blade width, blade perimeter, blade area and the number of rosette leaves are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S4

The TCP family of plant-specific transcription factors regulates plant phenotypes by controlling cell proliferation and differentiation, and is classified into class I and II genes. In Arabidopsis, class I TCP genes including AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP14, AtTCP15, AtTCP20, AtTCP21, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 reportedly regulate cell proliferation and leaf development by controlling the expression of cell-cycle genes [24,25,26,27]. Therefore, to investigate the roles of class I TCP genes in phenotypic alterations of leaves, we determined expression levels using qRT-PCR analyses. These experiments showed dramatic decreases in transcription of AtTCP15, AtTCP14, and AtTCP23 in OX plants and slight changes in the other type-I TCP genes, compared with those in WT plants (Fig. 5a). These data suggest that IbVPE1 affects leaf development by regulating class I TCP genes.

Expression levels of class I teosinte branched1/cycloidea/pcf (TCP) transcription factors and flowering-related genes; a AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP14, AtTCP15, AtTCP20, AtTCP21, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 expression levels in WT and OX plants; b LFY, AP1, SOC1, CO, FT, FRI, FLC, BN1, BN2, FPA, FVE, FCA, and LD expression levels in WT and OX plants; AtTublin was used as an internal control. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences; t-test, p < 0.05

In addition to alterations in leaf development, we observed early flowering in OX plants compared with their WT counterparts. Thus, we determined transcript levels of genes in 4 week-old wild type and transgenic plants, which have previously been associated with flowering, including LFY, AP1, SOC1, CO, FT, FRI, FLC, BN1, BN2, FPA, FVE, FCA, and LD. In these gene expression analyses, AP1 expression was significantly increased by around 20 fold and LFY expression was moderately increased in OX plants compared with WT plants. However, no differences in transcript levels of the other flowering-related genes were observed between OX and WT plants (Fig. 5b), indicating that IbVPE1 primarily accelerates flowering by upregulating AP1 expression.

IbVPE1 accelerates chlorophyll breakdown during dark-induced senescence

Because IbVPE1 expression was dramatically increased during sweetpotato leaf senescence, we determined whether IbVPE1 promotes leaf senescence. Chl catabolism is a clearly visible indicator of leaf senescence and fruit ripening, and the genes involved in Chl breakdown have been characterized in detail [24,25,26,27]. Thus, in the present study, we induced leaf senescence by placing detached leaves in the dark for 8 days and then investigated the roles of IbVPE1 in senescence induced Chl degradation. Under these conditions, WT leaves remained greener than OX leaves, indicating greater Chl retention over 8 days in darkness (Fig. 6a). To confirm these observations quantitatively, we analyzed Chl and observed significantly lower Chl contents in OX leaves than in WT leaves after only 2 days in the dark (Fig. 6b). Thus, to investigate whether decreases in chlorophyll contents were accompanied by changes in photosynthetic activities, we determined maximal quantum yields of photosystem II (PSII). In these experiments, WT leaves had typical Fv/Fm values of about 0.8, whereas the Fv/Fm ratios in OX leaves were around 0.65, suggesting relatively low PSII activity (Fig. 6c). In subsequent dark treatments, the Fv/Fm values in OX plants were decreased by an average of 40% compared with WT leaves after 4 days. However, Fv/Fm values were decreased by 15% in WT leaves after 4-days dark treatment and decreased further after 6 days, reflecting progressive impairment of PSII quantum efficiency (Fig. 6c). Previous studies show that the genes SGR, NYC1, PPH, PAO, and RCCH, are central to Chl breakdown. Accordingly, we showed that SGR, NYC1, PPH, and PAO expression levels were dramatically upregulated in OX leaves compared with WT leaves after dark treatments for 4 and 6 days (Fig. 6d-h). These results indicate that IbVPE1 actively stimulates the Chl breakdown pathway and accelerates leaf senescence.

Analysis of phenotypes, chlorophyll contents, PSII photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm), and expression levels of chlorophyll catabolism genes in detached leaves from WT and OX plants during dark-induced leaf senescence; a senescing phenotypes of detached leaves after 0, 2, 4, and 8 days in the dark; b chlorophyll contents in detached leaves from WT and OX plants were measured after 8-days dark treatment. c leaves were detached from WT and OX plants and Fv/Fm values were determined after 8-days dark treatment. d-h SGR, NYC1, PPH, PAO, and RCCR expression levels in detached leaves from WT and OX plants after 6-days dark treatment; AtTublin was used as an internal control. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences; t-tests, p < 0.05

Discussion

The VPE family of proteins was initially identified as a group of cysteine proteases with roles in the maturation of seed storage proteins in vacuoles [7, 28]. However, identification of structural and functional similarities with the apoptotic protein caspase-1 in tobacco plants led to consideration of the VPE family as mediators of plant cell death [12]. Subsequently, the roles of VPE in PCD were rapidly defined in experiments showing responses to various stress stimuli [29,30,31,32]. These studies obscured additional metabolic roles of VPEs, and these remain largely unknown. However, recent studies have demonstrated developmental roles of VPEs in tomato plants. In particular, suppression of SlVPE5 using a specific RNAi decreased the activity of acid invertase, which is involved in the hydrolysis of sucrose. Moreover, they found that the activity of this hydrolase was not fully correlated with mRNA expression in their RNAi-SlVPE5 plants [33], indicating post-transcriptional regulation of sucrose accumulation in fruit by SIVPE5. Similarly, post-transcriptional functions of SlVPE3 were related to the regulation of fruit ripening and disease resistance in tomatoes. In this study, SlVPE3 was required for cleavage of the serine protease inhibitor KTI4, which contributes to resistance against the fungal pathogen B. cinereal [34]. Hence, VPEs may harbor undiscovered physiological functions in plant development. Herein, we investigated the function of the sweetpotato VPE gene IbVPE1 using a convenient Arabidopsis overexpression model, and characterized the roles of IbVPE1 in plant development and leaf senescence. Although VPE has been associated with PCD during plant responses to environmental stress, pathogen infection, and sucrose accumulation [23, 33], our results demonstrate that transgenic expression of a sweet potato VPE (in IbVPE1) in Arabidopsis affects leaf morphology, flowering time and dark induced chlorophyll breakdown.

To identify functions of IbVPE1, we examined tissue and developmental stage specific expression patterns in sweetpotatoes. IbVPE1 expression was observed in all tissues but varied dramatically with developmental stages, with significantly higher expression in developing leaves and roots, and the highest expression in senescent leaves. Thus, to confirm the roles of IbVPE1 in development and senescence, we analyzed expression patterns of transgenic IbVPE1 in Arabidopsis tissues at various developmental stages. These experiments showed IbVPE1 expression in all tissues, and maximal expression in developing and senescent leaves. Relative IbVPE1 expression levels in Arabidopsis roots differed from that in sweetpotato.

IbVPE1 affects leaf development and flowering time by regulating class I TCPs and AP1

Consistent with the roles of IbVPE1 in leaf development, the present transgenic Arabidopsis plants had reduced rosette leaf sizes and numbers. Leaf sizes and shapes reflect cell division, differentiation, and expansion during leaf development [35, 36], and TCPs are well-characterized regulators of leaf development and determinants of leaf morphology [35, 37]. TCP genes encode a conserved domain with an amino acid non-canonical basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), which is involved in DNA binding and dimerization [38, 39]. In Arabidopsis, 24 TCPs have been identified, and these were previously subclassified into class I (13 proteins) and class II (11 proteins) transcription factors based on sequence homology [39]. Among class I TCP genes, AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP14, AtTCP15, AtTCP20, AtTCP21, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 regulate the expression of genes that are involved in shoot apical meristem and leaf development, and have similar functions to class II TCP transcription factors [40]. In loss-of-function studies, these genes were associated with leaf size, morphology, and flowering time, and TCP14 and TCP15 were shown to modulate cell proliferation in developing leaf blades and in specific floral tissues [41]. In addition, knockout of the class I TCP gene tcp23–1 reduced rosette leaf numbers and produced an early flowering phenotype [42] similar to that shown in the present study. Moreover, simultaneous mutation of tcp8, tcp15, tcp21, tcp22, and tcp23 altered leaf development traits in a study of Arabidopsis plants [43], suggesting that the present morphological observations in IbVPE1 OX plants reflect regulation of TCP transcription factors. Accordingly, the present transcriptional comparisons of 8 class I TCPs in leaves (Fig. 5a) showed dramatic changes in expression levels of the class II TCPs TCP14, TCP15, and TCP23 in IbVPE1 OX plants. The genes TCP14, TCP15, and TCP23 were previously subclassified with TCP8 and TCP22 and were shown to be clustered on chromosome1 [41], likely leading to general function redundancies, as indicated by comparisons of single and multiple TCP mutants, which showed only subtle and context dependent effects of individual TCP factors on cell proliferation. Hence, phenotypes reflect cumulative effects of multiple TCPs on cell division, requiring coordination of regulatory signals. In addition, the present observations of reduced rosette leaf sizes and numbers in IbVPE1 OX plants may follow a balance of decreased function and increased cell proliferation.

The present IbVPE1 OX Arabidopsis plants also exhibited an early flowering phenotype, as shown in a previous loss-of-function study of TCP23 [42]. Floral initiation is an important physiological switch from vegetative to reproductive states [44]. Subsequently, flowering times are strictly controlled by environment cues (day lengths, temperature, water, and nutrient availability) and endogenous signals (stages of development) to maximize reproductive success. Hence, whereas IbVPE1 influenced endogenous signaling pathways that regulate flowering under the present normal long-day conditions, further studies are required to decipher direct and indirect effects, or identify the affected transcription factors and hormones. Herein, we determined the expression levels of 13 flowering-related genes and observed a 10-fold increase in the transcription of AP1 and significant induction of LFY in IbVPE1 OX plants. AP1 reportedly activates the genes LFY and CAULIFLOWER to promote the formation of floral meristems (FM) [45,46,47,48,49]. In agreement, flower formation in the axils of sepals was inhibited in AP1 mutants, resulting in failure to establish FMs [48, 50, 51]. Taken with our results, these studies suggest that IbVPE1 alters the flowering times of Arabidopsis plants by up-regulating AP1 and LFY. But, it needs to be uncoverd that whether IbVPE affects those transcript levels ditrectly or indirectly.

Expression of IbVPE in Arabidopsis leads to accelerated chlorophyll breakdown via activation of chlorophyll catabolism during dark induced senescence

Numerous studies associate specific hormones and genes with initiation, promotion, and inhibition of senescence [52,53,54,55,56,57], and the induction of senescence likely reflects the combined effects of multiple factors. Among hormones of senescence, ethylene and cytokinin are known promoting and delaying factors, respectively, in higher plants [58, 59]. It is reported that several cysteine protease including vacuolar processing enzyme are highly induced by ABA-treatment in senescencing flower of daffodil [60] As is a strongly visible feature of leaf senescence, Chl breakdown is accompanied by degeneration of chloroplasts and disruption in photosynthesis [5, 6, 55, 56]. Although ethylene reportedly induces the expression of SlVPE3, which conversely regulates ethylene synthesis in tomatoes via a positive feedback loop [34], the functions of VPE in Chl catabolism and photosynthesis remain unknown.

Herein, we assessed dark-induced leaf senescence in IbVPE1 OX Arabidopsis plants because this process appears continuously in single rosette leaves rather than in whole plants [61]. These experiments showed that expression of IbVPE1 resulted in increased in transcription of genes encoding enzymes that are related to Chl catabolism, except for red Chl catabolite reductase (RCCR), during dark-induced leaf senescence. Similarly, Chl genes were reportedly upregulated in NO-deficient mutant nos1/noa1 plants with only slight reductions in RCCR expression during senescence, and RCCR activity was constant throughout leaf development [52, 62]. In agreement, the present chlorophyll contents and photosynthetic Chl fluorescence parameters (Fv/Fm) were decreased by IbVPE1 OX in detached leaves compared with those in detached WT leaves.

Conclusion

The present experiments demonstrate that IbVPE1 influences flowering times, leaf development, and senescence as well as the expression of flowering-related genes, such as TCP transcription factors and genes encoding Chl catabolism enzymes. These data suggest that, in addition to roles in PCD, VPEs influence development and senescence in Arabidopsis leaves. Further studies are required to elucidate post transcription and protein–protein interactions of IbVPE1 with developmental molecules in plants.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Branches of sweetpotato plants (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. cv Xu18) with 6–8 fully developed leaves were collected from the Institute of Agricultural Science, Xuzhou, Jiangsu, and were used in analyses of IbVPE1 expression levels. Leaves were divided into L1–L5 developmental stages according to sizes. L1–L5 stages are defined as unopened immature leaves, not fully-expanded immature leaves, fully-expanded mature leaves, and partial (early) and completely (late) yellowing senescent leaves, respectively. L3 mature leaves were collected from the position between 3 and 6 and were counted downward from the shoot apex. Various root samples, including fibrous roots (< 5 mm in diameter), pencil roots (< 15 mm in diameter), swollen roots (> 15 mm in diameter), and mature root, were collected at 4, 8, and 12 weeks, respectively, after planting.

Wild-type (Columbia, Col-0) and IbVPE1 overexpressing plants (OX lines) were grown under long day 16-h light/8-h dark conditions at 23 °C under 60% humidity in a soil mixture. For tissue-specific expression analyses, roots, stems, and leaves were collected at 30 days, and flowers and silique were collected upon appearance. For analysis developmental stages of roots and leaves, specimens were collected at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 days after planting.

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses

The IbVPE1 sequence was obtained by screening and sequencing the Xu18 fosmid library constructed by the Institute of Integrative Plant Biology, School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou. The amino acid sequence of IbVPE1 was decoded using ExPaSy translation tools (http://web.expasy.org/translate/). Other published VPE protein sequences were obtained from several databases using BLAST searches with the IbVPE1 gene sequence. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with MEGA 7.0 software. Amino acid sequences used to construct the tree are listed in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Construction of transgenes and plant transformation

Total RNA was isolated from sweet potato (Xu18) leaf sample using the Plant RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using GoScript™ Reverse transcription System (Promega). To generate IbVPE1 overexpression plants using Col-0 as background, the full-length coding sequence (CDS) of IbVPE1 was first amplified using the primers listed in Additional file 2: Table S1, and was then cloned into the cloning vector PBI121 via XbaI and SmaI restriction enzyme sites, and an IbVPE promotert was also cloned into PBI121:GUS via XbaI and SacI to generate PBI121-proIbVPE:GUS. Arabidopsis transformation was performed using vacuum infiltration [63] with the Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 strain.

Subcellular localization analysis

Subcellular localization analyse was performed with cloning the full length of the IbVPE1 CDS into pCAMBIA1300-GFP vector and the protein was fused in-frame with GFP for expression under the control of the CaMV35S promoter. The fused construct PCMBIA1301-35S:IbVPE1-GFP were transformed into onion epidermis cell by infiltration with the Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 strain and green fluorescent protein (GFP) signals were observed using a fluorescence microscope with 488-nm.

Phenotypic analysis

Numbers of rosette leaves were counted at the stage of bolting after elongating 0.5 cm of the main stem. Although cotyledons were not counted, petiole lengths, blade lengths, blade widths, blade perimeters, and blade areas of the fifth leaves were determined at bolting stage. Data were analyzed using LeafJ [64] with ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) as described previously [24].

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from samples using a plant RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Transcription analyses of genes were conducted using real-time PCR with a Rotor-Gene Q real-time thermal cycling system (Qiagen, CA, USA), QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kits (Qiagen, CA, USA), 200 ng RNA samples, 35 cycles and the primers listed in Additional file 2: Table S1 as described previously [65, 66].

Senescence induction

Dark-induced leaf senescence was achieved in leaves that were detached from plants for 3-weeks. The leaves were initially placed on petri dishes containing two layers of filter papers soaked in 15 ml of distilled water. Subsequently, petri dishes were covered with aluminum foil and were kept in the dark at 23 °C as described previously [52].

Chlorophyll measurements

After dark-induction, chlorophyll was extracted from leaves using 80% (V/V) acetone and chlorophyll contents were then determined using a spectrophotometer at wavelengths of 645 and 663 nm as described previously [52, 67].

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

The maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII was determined from the ratio of variable (Fv) to maximum (Fm) fluorescence (Fv/Fm) using a LI-6400XT Portable Photosynthesis system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska USA) as described previously [52].

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times and data are expressed as means ± SE. Differences between transgenic and wild-type (WT) plants were identified using Student’s t-test with SPSS Software (version 19.0), and were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Highlights

IbVPE1 regulates flowering times, leaf sizes and numbers, and senescence in A. thaliana plants.

Chlorophyll contents in IbVPE1 OX plants decreased more quickly than in WT plants under the condition of dark-induced senescence.

Abbreviations

- AP1:

-

APETALA1

- bHLH:

-

Basic helix-loop-helix

- BN1/2:

-

BRITTLE NODE1/2

- CO:

-

CONSTANS

- FLC:

-

FLOWERING LOCUS C

- FM:

-

Floral Meristems

- FRI:

-

FRIGIDA

- FT:

-

FLOWERING LOCUS T

- GFP:

-

Green Fluorescent Protein

- LD:

-

LU MINID EPENDENS

- LFY:

-

LEAFY

- NYC1:

-

NON-YELLOW COLORING1

- PAO:

-

PHEIDE A OXYGENASE

- PCD:

-

Programmed Cell Death

- PPH:

-

PHEOPHYTINASE

- PSII:

-

Photosystem II

- RCCH:

-

Red Chl catabolite reductase

- SGR:

-

STAY-GREEN

- SOC1:

-

Super of overexpression COI

- TCP:

-

Teosinite branched1/Cycloidea/Pcf

- TMV:

-

Tobacco Mosaic Virus

- VPEs:

-

Vacuolar Processing Enzymes

References

Qing T, Dongshu G, Baoye W, Fan Z, Changxu P, Hao J, Jinzhe Z, Tong W, Hongya G, Li-Jia Q, Genji Q. The TIE1 Transcriptional Repressor Links TCP Transcription Factors with TOPLESS/TOPLESS-RELATED Corepressors and Modulates Leaf Development in Arabidopsis. Plant Synthetic. 2013;25:421–37.

Yruela I. Plant development regulation: overview and perspectives. J Plant Physiol. 2015;182:62–78.

Fischer AM. The complex regulation of senescence. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2012;31:124–47.

Koyama T. The roles of ethylene and transcription factors in the regulation of onset of leaf senescence. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:650.

Hoertensteiner S. Chlorophyll degradation during senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:55–77.

Hoertensteiner S. Stay-green regulates chlorophyll and chlorophyll-binding protein degradation during senescence. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:155–62.

Hara-Nishimura I, Inoue K, Nishimura M. A unique vacuolar processing enzyme responsible for conversion of several proprotein precursors into the mature forms. FEBS Lett. 1991;294:89–93.

Wang Y, Zhu S, Liu S, Jiang L, Chen L, Ren Y, Han X, Liu F, Ji S, Liu X, et al. The vacuolar processing enzyme OsVPE1 is required for efficient glutelin processing in rice. Plant J. 2009;58:606–17.

Lu W, Deng M, Guo F, Wang M, Zeng Z, Han N, Yang Y, Zhu M, Bian H. Suppression of OsVPE3 enhances salt tolerance by attenuating vacuole rupture during programmed cell death and affects stomata development in rice. Rice. 2016;9:65.

Hiraiwa N, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. Vacuolar processing enzyme is self-catalytically activated by sequential removal of the C-terminal and N-terminal propeptides. FEBS Lett. 1999;447:213–6.

Rojo E, Martin R, Carter C, Zouhar J, Pan S, Plotnikova J, Jin H, Paneque M, Sanchez-Serrano JJ, Baker B, et al. VPEgamma exhibits a caspase-like activity that contributes to defense against pathogens. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1897–906.

Del PO, Lam E. Caspases and programmed cell death in the hypersensitive response of plants to pathogens. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R896.

Hara-Nishimura I, Kinoshita T, Hiraiwa N, Nishimura M. Vacuolar processing enzymes in protein-storage vacuoles and lytic vacuoles. J Plant Physiol. 1998;152:668–74.

Yamada K, Shimada T, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. A VPE family supporting various vacuolar functions in plants. Physiol Plantarum. 2005;123:369–75.

Kinoshita T, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. Homologues of a vacuolar processing enzyme that are expressed in different organs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:81–9.

Kinoshita T, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. The sequence and expression of the gamma-VPE gene, one member of a family of three genes for vacuolar processing enzymes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995;36:1555–62.

Nakaune S, Yamada K, Kondo M, Kato T, Tabata S, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. A vacuolar processing enzyme, deltaVPE, is involved in seed coat formation at the early stage of seed development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:876–87.

Grudkowska M, Zagdanska B. Multifunctional role of plant cysteine proteinases. Acta Biochim Pol. 2004;51:609–24.

Kinoshita T, Yamada K, Hiraiwa N, Kondo M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. Vacuolar processing enzyme is up-regulated in the lytic vacuoles of vegetative tissues during senescence and under various stressed conditions. Plant J. 1999;19:43–53.

Woltering EJ, van der Bent A, Hoeberichts FA. Do plant caspases exist? Plant Physiol. 2002;130:1764–9.

Hatsugai N, Kuroyanagi M, Yamada K, Meshi T, Tsuda S, Kondo M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. A plant vacuolar protease, VPE, mediates virus-induced hypersensitive cell death. Science. 2004;5685:855–8.

Nicholson DW. Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1028–42.

Hatsugai N, Yamada K, Goto-Yamada S, Nara-Nishimura I. Vacuolar processing enzyme in plant programmed cell death. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:234.

Rosybel Drury Stefan Hörtensteiner Iain Donnison Colin R. Bird Graham B. Seymour: Chlorophyll catabolism and gene expression in the peel of ripening banana fruits. Physiol Plant. 1999;107(1):32–38.

Herve C, Dabos P, Bardet C, Jauneau A, Auriac MC, Ramboer A, Lacout F, Tremousaygue D. In vivo interference with AtTCP20 function induces severe plant growth alterations and deregulates the expression of many genes important for development. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1462–77.

Selahattin Danisman, Froukje van der Wal, Stijn Dhondt, Richard Waites, Stefan de Folter, Andrea Bimbo, Aalt DJ van Dijk, Jose M. Muino, Lucas Cutri, Marcelo C. Dornelas, Gerco C. Angenent, Richard G.H. Immink: Arabidopsis Class I and Class II TCP Transcription Factors Regulate Jasmonic Acid Metabolism and Leaf Development Antagonistically. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:1511–23.

Li ZY, Li B, Dong AW. The Arabidopsis transcription factor AtTCP15 regulates endoreduplication by modulating expression of key cell-cycle genes. Mol Plant. 2012;5:270–80.

Haranishimura I, Takeuchi Y, Nishimura M. Molecular characterization of a vacuolar processing enzyme related to a putative cysteine of schistosoma-mansoni. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1651–9.

Kadono T, Tran D, Errakhi R, Hiramatsu T, Meimoun P, Briand J, Iwaya-Inoue M, Kawano T, Bouteau F. Increased anion channel activity is an unavoidable event in ozone-induced programmed cell death. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13373.

Deng M, Bian H, Xie Y, Kim Y, Wang W, Lin E, Zeng Z, Guo F, Pan J, Han N, et al. Bcl-2 suppresses hydrogen peroxide-induced programmed cell death via OsVPE2 and OsVPE3, but not via OsVPE1 and OsVPE4, in rice. FEBS J. 2011;278:4797–810.

Misas-Villamil JC, Toenges G, Kolodziejek I, Sadaghiani AM, Kaschani F, Colby T, Bogyo M, van der Hoorn RA. Activity profiling of vacuolar processing enzymes reveals a role for VPE during oomycete infection. Plant J. 2013;73:689–700.

Kim Y, Wang M, Bai Y, Zeng Z, Guo F, Han N, Bian H, Wang J, Pan J, Zhu M. Bcl-2 suppresses activation of VPEs by inhibiting cytosolic Ca2+ level with elevated K+ efflux in NaCl-induced PCD in rice. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2014;80:168–75.

Wang N, Duhita N, Ariizumi T, Ezura H. Involvement of vacuolar processing enzyme SlVPE5 in post-transcriptional process of invertase in sucrose accumulation in tomato. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;108:71–8.

Wang W, Cai J, Wang P, Tian S, Qin G. Post-transcriptional regulation of fruit ripening and disease resistance in tomato by the vacuolar protease SlVPE3. Genome Biol. 2017;18:47.

Nath U, Crawford BC, Carpenter R, Coen E. Genetic control of surface curvature. Science. 2003;299:1404–7.

Kuchen EE, Fox S, de Reuille PB, Kennaway R, Bensmihen S, Avondo J, Calder GM, Southam P, Robinson S, Bangham A, et al. Generation of leaf shape through early patterns of growth and tissue polarity. Science. 2012;335:1092–6.

Palatnik JF, Allen E, Wu X, Schommer C, Schwab R, Carrington JC, Weigel D. Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature. 2003;425:257–63.

Aggarwal P, Das GM, Joseph AP, Chatterjee N, Srinivasan N, Nath U. Identification of specific DNA binding residues in the TCP family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1174–89.

Cubas P, Lauter N, Doebley J, Coen E. The TCP domain: a motif found in proteins regulating plant growth and development. Plant J. 1999;18:215–22.

Uberti-Manassero NG, Lucero LE, Viola IL, Vegetti AC, Gonzalez DH. The class I protein AtTCP15 modulates plant development through a pathway that overlaps with the one affected by CIN-like TCP proteins. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:809–23.

Kieffer M, Master V, Waites R, Davies B. TCP14 and TCP15 affect internode length and leaf shape in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011;68:147–58.

Balsemao-Pires E, Andrade LR, Sachetto-Martins G. Functional study of TCP23 in Arabidopsis thaliana during plant development. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2013;67:120–5.

Aguilar-Martinez JA, Sinha N. Analysis of the role of Arabidopsis class I TCP genes AtTCP7, AtTCP8, AtTCP22, and AtTCP23 in leaf development. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:406.

Shrestha R, Gomez-Ariza J, Brambilla V, Fornara F. Molecular control of seasonal flowering in rice, arabidopsis and temperate cereals. Ann Bot. 2014;114:1445–58.

Bowman JL, Alvarez J, Weigel D, Meyerowitz EM, Smyth DR. Control of flower development in Arabidopsis thaliana by APETALA1 and interacting genes. Development. 1993;119:721–43.

Kempin SA, Savidge B, Yanofsky MF. Molecular basis of the cauliflower phenotype in Arabidopsis. Science. 1995;267:522–5.

Mandel MA, Yanofsky MF. A gene triggering flower formation in Arabidopsis. Nature. 1995;377:522–4.

Han Y, Jiao Y. APETALA1 establishes determinate floral meristem through regulating cytokinins homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2015;10:e98903911.

Ferrandiz C, Gu Q, Martienssen R, Yanofsky MF. Redundant regulation of meristem identity and plant architecture by FRUITFULL, APETALA1 and CAULIFLOWER. Development. 2000;127:725–34.

Irish VF, Sussex IM. Function of the apetala-1 gene during Arabidopsis floral development. Plant Cell. 1990;2:741–53.

Mandel MA, Gustafson-Brown C, Savidge B, Yanofsky MF. Molecular characterization of the Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene APETALA1. Nature. 1992;360:273–7.

Liu F, Guo F. Nitric oxide deficiency accelerates chlorophyll breakdown and stability loss of thylakoid membranes during dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e563452.

Quirino BF, Noh YS, Himelblau E, Amasino RM. Molecular aspects of leaf senescence. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:278–82.

Buchanan-Wollaston V, Earl S, Harrison E, Mathas E, Navabpour S, Page T, Pink D. The molecular analysis of leaf senescence - a genomics approach. Plant Biotechnol J. 2003;1:3–22.

Jing HC, Hille J, Dijkwel RR. Ageing in plants: conserved strategies and novel pathways. Plant Biol. 2003;5:455–64.

Guo YF, Gan SS. Leaf senescence: Signals, execution, and regulation. In: Schatten GP, editor. Current Topics in Developmental Biology; 2005. p. 83.

Lim PO, Kim HJ, Nam HG. Leaf senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:115–36.

Gan SS, Amasino RM. Inhibition of leaf senescence by autoregulated production of cytokinin. Science. 1995;270:1986–8.

Grbic V, Bleecker AB. Ethylene regulates the timing of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1995;8:595–602.

Hunter DA, Ferrante A, Vernieri P, Reid MS. Role of abscisic acid in perianth senescence of daffodil (narcissus pseudonarcissus “dutch master”). Physiol Plant. 2004;121:313–21.

Hensel LL, Grbic V, Baumgarten DA, Bleecker AB. Developmental and age-related that influence the longevity and senescence of photosynthetic tissues in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1993;5:553–64.

Pruzinska A, Tanner G, Aubry S, Anders I, Moser S, Muller T, Ongania KH, Krautler B, Youn JY, Liljegren SJ, et al. Chlorophyll breakdown in senescent Arabidopsis leaves. Characterization of chlorophyll catabolites and of chlorophyll catabolic enzymes involved in the degreening reaction. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:52–63.

Bechtold N, Pelletier G. In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;82:259–66.

Maloof JN, Nozue K, Mumbach MR, Palmer CM. LeafJ: an ImageJ plugin for semi-automated leaf shape measurement. J Vis Exp. 2013:71:50028.

Kwak KJ, Kim YO, Kang HS. Characterization of transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GR-RBP4 under high salinity, dehydration, or cold stress. J Exp Bot. 2005;56:3007–16.

Gu L, Jung HJ, Kim BM, Xu T, Lee K, Kim Y, Kang H. A chloroplast-localized S1 domain-containing protein SRRP1 plays a role in Arabidopsis seedling growth in the presence of ABA. J Plant Physiol. 2015;189:34–41.

Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts polyphenoloxidase polyphenoloxidase in beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15.

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers and the editor for their helpful suggestions to improve the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Tao Xu (School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, China) and Jianying Sun (School of Life Science, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, China) for their help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771367), The Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-10-B3). The fundings have no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this manuscript are included within the article and its additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZL and YH designed the research. JJ, JH, and RT performed the experiments. JJ, JH, YH, and ZL analyzed the results. JJ, JH, YH, and ZL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Amino acid sequences of the plant VPEs used to construct the phylogenetic tree and databases used to retrieve the VPE amino acid sequences. (PDF 280 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Gene-specific primers used in full-length cDNA and RT-PCR analysis (PDF 80 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, J., Hu, J., Tan, R. et al. Expression of IbVPE1 from sweet potato in Arabidopsis affects leaf development, flowering time and chlorophyll catabolism. BMC Plant Biol 19, 184 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1789-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1789-8