Abstract

Background

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi form symbiotic associations with host plants can protect host plants against diverse biotic and abiotic stresses, and promote biodegradation of various contaminants. However, the molecular mechanisms of how the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and host plant association on atrazine stress were still poorly understood. To better characterize how arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and host plant interactions increase atrazine stress, we performed physiological and proteomic analysis of Funneliformis mosseae (mycorrhizal fungi) and Medicago sativa (alfalfa) association under atrazine stress.

Results

The results showed that in the Arbuscular mycorrhizal, protective enzymes were up regulated and the malondialdehyde content increased relative to those of non-mycorrhizal M.sativa. We also examined the atrazine degradation rates within the nutrient solution, and a 44.43% reduction was observed with the mycorrhizal M.sativa, with 30.83% of the reduction attributed to F. mosseae. The accumulation content in root and stem of mycorrhizal M.sativa were obviously increased 11.89% and 16.33% than those of non- mycorrhizal M.sativa. The activity of PPO, POD, CAT and SOD in mycorrhizal M.sativa were obviously higher than non mycorrhizal M.sativa under atrazine stess. We identified differential root proteins using isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantization coupled with liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, with 533 proteins identified (276 unregulated and 257 downregulated). The differentially expressed proteins were further examined using GO, BLAST comparisons, and a literature inquiry and were classified into the categories of atrazine degradation (37.1%); atrazine stress response (28.6%); plant immune responses (14.3%); translation, synthesis, and processing (10%); and signal transduction and biological processes (10%). Furthermore, we identified glycosyl transferase, glutathione S-transferase, laccase, cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, peroxidase, and other proteins closely related to the degradation process.

Conclusions

Mycorrhizal Medicago showed improved atrazine degradation within the culturing medium and increased atrazine enrichment in the roots and stems. Additionally, AMF increased the plant root response to atrazine, with relevant enzymes up regulated and toxic effects alleviated. Overall, the findings of this study show that AMF played an important role in easing atrazine stress in plants and contributed to atrazine remediation and further contributed to the understanding of the molecular mechanism associated with atrazine stresses and potential mycorrhizal contributions in M.sativa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atrazine is an herbicide widely used in agriculture and forestry to control most broadleaf and some gramineous weeds. Atrazine applications span decades [1], despite causing serious harm to the ecosystem and with some studies indicating that the herbicide acts as an endocrine disruptor in humans and animals [2]. In China, atrazine pollution accidents have subsequently rendered large areas of farmland unusable because of toxicity and have resulted in billions of dollars of economic losses [3]. Therefore, an approach that reduces or eliminates the toxic effects of atrazine is of the utmost importance.

In previous studies that examined methods of atrazine degradation, approaches include chemical methods, such as photolysis [4] and hydro carbonylation [5]; physical methods, such as ion-exchange [6] and adsorption on activated carbon fibres [7]; and biological methods, including bacterial [8], fungal [9],and plant [10] remediation. Of these methods, the utilization of fungal–plant interactions is the most environmentally friendly. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) possess several characteristics that make them attractive for use in the atrazine degradation process. First, AMF are well adapted to the environment and can withstand drought [11], soil salinization [12], heavy metals [13], and other adverse conditions [14]. Additionally, AMF can be used as a biological fertilizer in soil pollutant remediation because the physical and chemical properties of the soil improve to maintain fertility [15]. AMF also serve as a plant “organ” and expand nutrient absorption via abundant external hyphae [16]. Last, AMF can increase plant defence capabilities and mitigate damage in cases of root [17] or soil-borne [18] diseases.

At present, various studies have used mycorrhizal biotechnology in the remediation of atrazine-contaminated soil and obtained positive results [19, 20]. Previously, our lab found that the addition of Glomus mosseae (mycorrhizal fungi) to atrazine-contaminated soil (concentration of 50 mg/kg) achieved a 91.6% degradation rate, with 22.6% of that the mycorrhizal contribution [21]. In a similar study, transcriptome sequencing identified 172 significantly up-regulated genes closely related to atrazine degradation and discovered that extracellular enzymes are the key to atrazine degradation [22]. Additionally, late in the atrazine degradation process, with a mycorrhizal symbiont, metabolites were varied [23]. However, most studies focus on transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches, with few studies examining proteomic alterations associated with atrazine stress. When examining the mechanisms associated with plant stress resistance, many studies rely on proteomic approaches. Recently, many proteomic technologies, such as two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE), difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE), protein arrays, label-free quantification, and isobaric tags for relative and absolute transcriptome (iTRAQ), have been utilized to identify differential expression associated with various components of animals, microorganisms, plants, and human cells [24].

In recent years, with the deepening of research on soil organic pollution remediation, the use of plant-microbial joint restoration has become an important development direction of soil bioremediation technology. Although there are many studies on AMF improving plant stress resistance, but there are still few studies on how AMF and host respond to stress, hence it is necessary to strengthen the theoretical study of mycorrhizal fungi. In this study, we utilized iTRAQ to identify differential expression in the roots of mycorrhizal Medicago sativa (alfalfa) relative to non-mycorrhizal M. sativa during atrazine stress. The aim of this study was to further examine plant responses to atrazine stress at the proteomic level and to better characterize the mechanisms associated with atrazine tolerance during a plant–fungus symbiosis. The findings presented herein provide a theoretical basis for pesticide remediation in agricultural ecosystems, aid in environmental protection, and promote the sustainable development of eco-agriculture.

Results

Mycorrhizal colonization rate in M.sativa

After 10 days of G.mosseae and M.sativa co-culture, only a few hyphae were detected in some roots and no vesicles appeared, thereby indicating a low infection rate. As plant growth increased, the fungal reproductive capacity also gradually increased, thereby increasing the infection rate (Fig. 1a). After 45 days, the inoculated roots were filled with hyphae and vesicles (Fig. 1b), with a mycorrhizal infection rate of 91.63%. In the CK group, no hyphae were detected, which indicated that no indigenous AMF were in the culture medium.

AMF colonization rate changes overtime and representative image of AMF colonization. Note: (a) represents AMF colonization rate changes. (b) represents photomicrograph of structural colonization of AMF in the root of Glomus mosseae. CK, non-mycorrhizal without atrazine stress (0 mg/L); AM, mycorrhizal without atrazine stress (0 mg/L); Error bars represent the standard error of mean of three replicates (n = 100). AR: Arbuscule; V: Vesicles

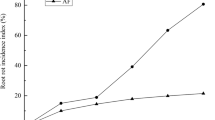

Atrazine content in the nutrient solution and M.sativa tissue

We measured atrazine content in the nutrient solution at 2, 4, and 6 days post-atrazine treatment in the AM and CK groups. The atrazine concentrations gradually decreased from the initial concentration of 0.5 to 0.28 mg/L in the AM group and to 0.33 mg/L in the CK group. The atrazine removal rates were 44.43% in AM and 33.96% in CK (Fig. 2), with the removal rate significantly higher in the AM than in the CK group (p < 0.05).

Additionally, we examined atrazine accumulation in roots and stems (Fig. 3), and levels increased significantly on days 4 and 6 compared with those on day 2 (p < 0.05). The roots absorbed more atrazine than the stems in both groups, but the AM group had higher levels in the roots (11.89%) and stems (16.33%) overall by day 6 than those in the CK group.

To show the changes in atrazine accumulation or metabolism directly, we determined bioaccumulation coefficient (BCF) and transfer coefficient (TF) values (Table 1). In the AM group, the BCF values of the roots and stems were 0.17 and 0.08, respectively, and in the CK group, they were 0.13 and 0.06, respectively; which were not significantly different. However, these findings suggested that the reduction of atrazine in the culture medium was predominately due to plant or natural degradation rather than absorption by the plant. When examining the TF values, the AM group had a higher value than that of the CK group, which showed that the AM group was better able to shift the pesticide from the underground region to the upper region. These results show that AMF can improve the ability of plants to absorb, transport, and metabolize atrazine.

Examination of malondialdehyde (MDA) and praline (pro) content following atrazine stress

During atrazine stress, the MDA and Pro contents in the roots of both groups showed a downward trend with time (Fig. 4). By day 6 post-atrazine treatment, the MDA content of the AM group was significantly lower than that of the CK group (p < 0.05; 11.03%), whereas the Pro content was significantly higher than that of the CK group (p < 0.05; 53.96%). Before reaching day 6, the MDA content in the AM group (7.52%) was lower than that in the CK group, and the Pro content increased by 40.32% compared with that of the CK group.

Examination of MDA and Pro content in M.sativa roots during atrazine stress. Note: 0 CK, non-mycorrhizal without atrazine stress (0 mg/L); 0 AM, mycorrhizal without atrazine stress (0 mg/L); 0.5 CK, non-mycorrhizal with atrazine stress (0.5 mg/L); 0.5 AM, mycorrhizal with atrazine stress (0.5 mg/L); Columns represent the means for three replicates (n = 3). Error bars show the standard error. Columns with different letters indicate significant differences between treatments at P < 0.05

Examination of root protective enzyme activities during atrazine stress

We examined four stress-related enzymes: polyphenoloxidase (PPO), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (Fig. 5). PPO is a type of copper binding enzyme that is widely found in plants, animals, and fungi and participates in biological oxidation. When an organism is experiencing stress, PPO is in an active state. Following atrazine stress, root PPO levels showed an upward trend (Fig. 5a), with the AM group showing significantly higher levels than those of the CK group by day 6 (p < 0.05; 26.31). When examining the AM and CK groups not exposed to atrazine stress, PPO activity remained consistent throughout, and no significant differences were noted between the groups.

Changes in (a) PPO, (b) POD, (c) CAT, and (d) SOD activities in different days. Note: 0 CK, non-mycorrhizal without atrazine stress; 0 AM, mycorrhizal without atrazine stress; 0.5 CK, non-mycorrhizal with atrazine stress (0.5 mg/L); 0.5 AM, mycorrhizal with atrazine stress (0.5 mg/L); Columns represent the means for three replicates (n = 3). Error bars show the standard error. Columns with different letters indicate significant differences between treatments at P < 0.05

The enzyme POD was also examined, which is closely associated with plant photosynthesis and respiration intensity. POD, via an H2O2 electron acceptor, removes phenol and amine substances that are harmful and reduces H2O2, phenol, and amine toxicity. In M.sativa roots under atrazine stress, POD activity levels increased first and then decreased (Fig. 5b); with the activity in the AM group significantly higher than that in the CK group throughout (p < 0.05) and 37.51% higher by day 6. In the groups not exposed to atrazine stress, POD showed a slight upward trend, with POD levels in the AM group significantly higher than those in the CK group (p < 0.05).

CAT plays an important role in biological defences and is key to the maintenance of low H2O2 levels. CAT catalyses the decomposition of H2O2 into water and molecular oxygen, with iron porphyry as the auxiliary base, thereby reducing toxicity. During atrazine stress, the root CAT activity in the AM group showed a significant upward trend relative to that in the CK group (p < 0.05; Fig. 5c), with levels 41.2% higher by day 6. In the groups not under atrazine stress, CAT activity did not change significantly (p < 0.05).

SOD is a metal-containing enzyme that removes active oxygen free radicals, thereby preventing functional, compositional, and structural oxidative damage. In roots under atrazine stress, SOD activity levels first increased and then decreased (Fig. 5d). At day 4, activity levels peaked and then dipped on day 6, with activity levels significantly higher in the AM group than those in the CK group (p < 0.05; 70.29%). In the groups with no atrazine stress, SOD activity was significantly higher in the AM group than that in the CK group for all time points except for day 6 (p > 0.05). These findings suggest that during atrazine stress, many reactive oxygen species are produced; thus, PPO, POD, CAT, and SOD activities increase to offer a protective effect. The higher levels of enzyme activities observed in the AM than in the CK group suggested that those plants more effectively alleviated atrazine stress.

The identification of differential proteins during atrazine stress

We identified differential proteins using iTRAQ coupled with liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS), with 533 proteins identified in total. Significantly up-regulated proteins had to meet the condition of AM/CK > 1.2, whereas significantly down-regulated proteins had to satisfy AM/CK < 0.83.A total of 533 proteins were differential proteins, with 276 up regulated and 257 down regulated. Following GO and BLAST analyses (Fig. 6), these proteins were classified into five categories, including atrazine biodegrading (37.1%); proteins related to atrazine stress response (28.6%); proteins that participate in plant immune responses (14.3%); protein translation, synthesis, and process-related proteins (10%); and proteins associated with signal transmission and biological processes (10%; see Table 2).

Discussion

Effects of atrazine on the physiological indexes of M. sativa

Previous studies suggest that MDA, Pro, and antioxidant activity within the root system during adverse stress are an indication of the ability to manage pollutant stress at different levels [25], with Pro having a buffer effect during stress [26]. In this study, plants rapidly synthesized large amounts of Pro at the start of atrazine stress, with levels then decreasing over time. At first, these findings appear in contrast to previous findings [27]; however, the prolonged atrazine stress might have exceeded tolerance, which led to metabolic and osmoregulatory disorders that resulted in a loss of proline.

Levels of MDA and PPO are used as indicators of the degree of cell membrane damage and degree of stress [28] and in this study, indicated that cell membrane damage occurred during atrazine stress. The MDA content decreased with increased time of stress, indicating that the atrazine affects were better tolerated with time [29], whereas SOD, PPO, POD, and CAT continuously increased. Previous studies show that after stress induction, plant antioxidant enzyme activity first increases and then decreases [30]. However, the findings in this study differed, which suggested that M.sativa resistance mechanisms during atrazine stress did not depend entirely on antioxidant enzyme activity. Additionally, the root Pro levels were consistently higher in the AM group than in the CK group, whereas the MDA content was always lower than that of the CK group. These findings suggested that AMF played an important role in alleviating atrazine stress, which is consistent with previous studies that show AMF can increase stress resistance [31, 32].

Differential protein expression associated with atrazine stress

When plants enter symbiosis with AMF, the process is continuous and dynamic and includes the stages of pre-symbiosis, early symbiosis, and symbiotic maturity [33], with the development of special mycorrhizal structures and physiological characteristics [34]. In this study, we identified differentially expressed proteins associated with atrazine stress using iTRAQ coupled with LC-MS. The identification of these proteins contributes to a better understanding of the resistance mechanism associated with atrazine stress.

Proteins associated with atrazine biodegradation

Of the differential proteins associated with mycorrhizal Medicago, 26 were associated with atrazine biodegradation and included cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, glycosyltransferase, glutathioneS-transferase (GST), laccase, and peroxidase. Currently, various studies show that the P450 gene is directly involved in the process of pesticide degradation [35, 36] and significantly improves tolerance to substances such as isopropyl methylamine, atrazine, and ethylamine [37]. Additionally, P450 is essential in the biosynthesis of plant photochemical compounds and plays a crucial role in resisting pathogens [38].

Glycosyltransferase also plays an important role in regulating exogenous pollutants [39] by improving the target pollutant hydrophilicityvia UDP-glucose, which is regarded as an aglycosylation donor. This alteration then activates membrane transport and influences solubility to ultimately turn the toxic target pollutant into a low-toxicornon-toxic substance [40, 41]. During the early stage of atrazine stress, previous studies find that glycosyl transferase transcriptional levels increase [21]. In this study, protein levels varied; thus, further exploration into the role of glycosyltransferase in atrazine degradation is required.

The GST gene family encodes enzymes that degrade harmful exogenous chemicals [28] and serve as antioxidants [42], and these enzymes are found in wheat, sorghum, alfalfa, and other crops [43]. In this study, three GST proteins were up regulated and one was down regulated. These results may be associated with the M. sativa activating mechanisms that are associated with reactive oxygen species in response to atrazine stress and result in increased antioxidant levels and their associated mechanisms.

During pesticide stress, biodegrading enzymes, such aslaccase, peroxidase, catalase, lipase, and glutaredoxin [44, 45], are secreted. In this study, two laccases and nine peroxidases were up regulated in the AM group relative to these enzymes in the CK group. Laccase predominantly participates in lignin synthesis but also has a close association with plant disease resistance [46, 47]. In one study, the GaLAC1 gene from cotton was transfected into Arabidopsis thaliana and increased eugenic acid and mustard acid tolerance [48]. In a study examining transgenic tobacco that contained a tomato TPX2 peroxidase gene, the transgenic variety showed increased ability to retain water with improved germination rate and salt resistance [49]. Additionally, in ginkgo exposed to heavy metal pollution, the ginkgo peroxidase gene (GbPOD1) was implicated in the defence and removal of the heavy metals [50]. Furthermore, our previous study also showed a similar expressional trend for these two types of enzymes [22]. Although these enzymes appeared to contribute to the synergistic degradation of atrazine and protect the plant at the physiological and protein levels, further examination is required to determine their exact mechanisms.

Proteins associated with atrazine stress responses

Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitors can inhibit protease hydrolysis and protect other defensive proteins from degradation, in addition to also regulating endogenous protease activity and preventing disease [51]. One study found that when cotton cultivars were transfected with soybean Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitors, they were more resistant to pesticides [52]. Therefore, Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitors have the potential to increase pesticide resistance when utilized in genetic engineering.

Plant growth can be modulated via methylation levels during external stress. In this study, the 2OG-Fe (II) oxygenase family of oxidoreductases increased in the AM group, which is involved in the process of converting 5-mctransmethylation into 5-hmC and 5-fc. To some extent, the genes within this family are present across many protein networks [53] and co-coordinate plant stress responses.

Chitinase catalyses the synthesis of chitin and dextran linear polysaccharide chains in plants and also plays an important role in the process of fungal infection [54]. In the present study, chitinase was up regulated in the AM group relative to that in the CK group both with and without atrazine stress, which indicated that the mycorrhizal association might contribute to an increase in stress resistance.

Heat shock proteins aid in damage protection and can even repair damaged proteins [55]. One study showed that heat shock proteins play an important role in resisting exogenous organic compounds, such as anthracene and pyrene [56]. Furthermore, one study showed that two wheat heat shock proteins offered protection in the presence of organic toxicants [57]. In the body, these proteins participate in protein folding and assembly and strengthen the ability to respond to external stress. In this study, heat shock expression increased in mycorrhizal Medicago, thereby improving atrazine tolerance.

Lectin, which can recognize mannose, chitin, and t-antigens, is an important glycoprotein that increases during mycorrhizal establishment and promotes physiological plant functions [58]. In white kidney beans, lectin may provide an inhibitory effect against melon blight and grape grey mildew [59]. Similar to lectin, defensin-like proteins also serve in a protective capacity, and a sweet pepper defensin element transformed into E.coli conferred antibacterial activity [60]. In this study, a defens in-like protein and lectin were up regulated in the AM group, which suggested that the mycorrhizal symbionts had increased tolerance to atrazine stress.

Ethylene, which is important in fruit maturation, is formed when 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase associates with catalysed 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylicacid (ACC) [61]. In one study, weeds expressing the ACC gene were resistant to the hormone herbicide chloroquinoline [62]. Another protein that also functions similarly to ACC is the polygalacturonase inhibitor protein, which is as pecificheat-stablegly co-protein. Additionally, one study found a correlation between responses to endurance to mechanical injury and low temperature stress [63]. In this study, the polygalacturonase inhibitor protein and 1-aminocycloproclopropane-1-carboxylateoxidase were up regulated in the AM group and presumably contributed to atrazine tolerance.

Plant immune response-related proteins

When a plant is exposed to viruses or organic toxicants, the immune response is stimulated. The syntaxin protein (SYP), which is a member of the SNARE (soluble N-ethyl-male antibody-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein) protein family, functions in vesicle-mediated transport in plant cells. The SYP gene is associated with plant abiotic stresses, cytoplasmic division, gravity response, lipi drafting, and plant disease resistance [64]. In one study, the loss of the AtSYP121 gene due to bacterial infection resulted in an increase in fungal penetration and the destruction of plant viral defences [65]. Moreover, the AtSYP121 gene is implicated in the salicylicacid, jasmonicacid, and ethylene-dependent defence pathways.

Pathogenesis-related protein (PR)is induced by a variety of exogenous stimulating factors (pathogens and organic pollutants, among others) and endogenous factors (plant hormones, ethylene, salicylic acid, and hydrogen peroxide, among others). The expression of this protein is closely related with plant protoplast embryogenesis, the germ formation of the callus, and the regulation of hormones (auxin IAA and cytokine in CTA) in the process of germ formation [66, 67]. The accumulation of PR protein is significantly correlated with stress intensity [68]. In this study, two PR proteins were up regulated and one was down regulated in the AM group. Mycorrhizal associations allow plants to respond quickly to stress [69], but in this study, the PR levels were only gradually reduced rather than completely reduced, possibly because of a gradual decrease in the basic metabolic capacity and productivity of the plant. Therefore, we speculate that the observed PR expression in the AM group alleviated the effects of atrazine stress on plant growth.

The biological function of lignin includes limiting the mechanical damage to plant cells and tissues and also forming a natural barrier that can hinder various pathogens. Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) is a key catalytic enzyme in the process of plant lignin synthesis. Lignin content is modulated by various transcription factors, such as NAC, MYB, and zinc finger transcription factors [70]. When the COMT gene or protein expression is down regulated, the lignin content is also reduced, and plant resistance to exogenous substances is weakened. In this study, COMT expression was up regulated in the AMF symbionts, which suggested an increase in resistance to atrazine stress relative to that of the control group. Cysteine-rich secretory proteins (CRISPs) are found in the mammalian reproductive tract, with their expression level closely associated with the regulation of the human immune system and a variety of major human diseases. COMT also has been examined as a potential biomarker and drug therapy target [71]. Although not well characterized in plants, COMT is regulated by negative feedback and produces osmotic substances and detoxification substances and regulates closure to reduce cell membrane injury [72]. In this study, AMF symbionts showed an up-regulation of COMT, suggesting a protective function during atrazine stress.

Proteins relating to translation, synthesis, and processing

The processes of translation, synthesis, and processing are subjected to various levels of regulation. Ribosomal proteins exist in the ribosome, and their synthesis is controlled by the activity of the GTP enzyme. The functions of ribosomal proteins are complicated and not fully elucidated, but how the ribosome forms during translation is clear. One study reported an up-regulation of ribosomal proteins when wheat under high temperature stress was treated with growth regulators (coronamic acid, COR) [73]. In this study, ribosomal proteins were up regulated in the AM group relative to that in the control, indicating increased protein synthesis. Protein disulfide isomerase-like protein (PDIL) has a disulfide bond that inhibits the formation of erroneous positions between cysteines by regulating the dox pathway in the cytoplasm during rapid peptide folding [74]. In our study, PDIL was unregulated in the AM group during atrazine stress, which indicated a suppression of erroneous positions during semi synthesis and increased adapt ability during stress.

Proteins associated with signal transduction and biological processes

Plants associated with AMF show in creased ability to resist biological or abiotic stresses. Mycorrhizal associations involve complex recognition signals and a complex biological metabolism [75, 76]. In this study, Nodulin13 expression was unregulated, which indicated that the mycorrhizal symbionts could degrade atrazine. Leghemoglobin Lb120–1 is a pigment in plant nodules that is similar to vertebrate my glob in and plays an important role in plant nitrogen fixation, nodulation, maintenance of the intracellular environment, and ATP production [77]. The soybean plant Lb120–1 expression is not detected until rhizobia nodule formation is detected [78]. In the AM group, compared with the CK group, Lb120–1 expression was unregulated, which suggested that this group was more robust and therefore more able to tolerate atrazine stress.

Serine/threoninekinase (STK)–related proteins function in signalling and are involved in the physiological responses of most cells [79]. Previous studies show that STKs are involved in plant defence responses, with activity modulated by low temperature, soybean mosaic viral infection, or other factors [80]. In this study, STK expression was unregulated in the AM group, which indicated an atrazine tolerance. AT-hook plays an important role in transcriptional regulation by serving as acofactor modulating chromosomal structure and as a transcription factor [81]. DNA-binding proteins containing AT-hook motifs are found in humans, insects, and plants [82]. One study examining the AT-hook gene family in rice found expression during development, particularly in the rice seedling stage, indicating a role in plant growth and metabolism [83]. In this study, AT-hook expression was down regulated in the AM group, which suggested a possible alternative function in stress response, but further examination is required.

Network interaction predictions based on differential expression

We predicted target proteins using PPI analysis in CytoScape (3.2.1), with the target proteins (direct and indirect interactions) located in the IntAct database. These interactions included the direct physical proteins and the indirect proteins correlated with indirect functions. The key proteins that affected the entire metabolic system or signal transduction pathways are shown in Fig. 7. The results showed that phenylalanine ammonia-lyase protein (PAL-1) was the most correlated protein, directly or indirectly, with connections to proteins such as peroxidase, GLYMA02G40040.1, trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase, and GLYMA15G13510.1. Additionally, most of the target proteins were associated with PAL1 and were in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 8); thus, this pathway might play an important role in stress tolerance. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase has a special sub cellular localization and can function in cellular metabolism, plant development, and other biological transmission processes. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase interacts with various peroxidases, thereby participating in alfalfa phenylpropanoid biosynthetic processes, and modulates phenyl propane metabolites and stress responses. These findings showed that the atrazine stress response is a multi-factor process involving many protein interactions.

Protein-interaction network interactions for differentially expressed proteins. Note: a shows the integrated network for all the differentially expressed proteins; b shows the network interactions for the differentially expressed proteins related with phenylpropanoid pathway. Red triangle represents the differentially expressed proteins related with phenylpropanoid pathway; Green circle represents other differentially expressed proteins, respectively. The sizes represent the abundance of differentially expressed proteins

Molecular patterns of AM-M. sativa response to atrazine stress

Molecular modelling of mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal M. sativa under atrazine stress was conducted (Fig. 9). The right side of the figure represents the AM group under atrazine stress, the left side depicts the CK group under atrazine stress, and the middle represents the physical properties. When atrazine stress began in the AM group, expression was altered relating to regulatory factors (Nodulin-13, Lb120–1, STK, and AT-hook), specific proteins (CRISPs, COMP, and ribosomal), degradation proteins (oxidoreductase, chase, oxidative, lectin, and oxidase), and immune proteins (SYP and PR), thereby promoting stress tolerance. Additionally, the physiological indicators showed that antioxidant enzymes increased, thereby decreasing peroxide products and improving the osmotic adjustments. The ability of AMF to induce atrazine resistance in M. sativa at the protein level was primarily achieved by the regulation of the antioxidant system, transport of harmful substances and metabolic system, the signal delivery system, and the immune system. The associations and timing related to these physiological processes require further examination.

Conclusions

Medicago sativa growth was significantly inhibited by atrazine, with growth improved in mycorrhizal symbionts. Furthermore, mycorrhizal M.sativa showed improved atrazine degradation within the culturing medium and increased atrazine enrichment in the roots and stems. Additionally, AMF increased the plant response to atrazine, with relevant enzymes up regulated and toxic effects alleviated. The actions of AMF were primarily mediated by the antioxidant system, transport and metabolic systems, and signal delivery system. Overall, these findings show that AMF played an important role in easing atrazine stress in plants and contributed to atrazine remediation.

Methods

Pot experiment design

Atrazine (99% purity) was purchased from China Bailingwei (Shijiazhuang City, China), and the atrazine commodity drug (38% purity) was purchased from Autumn Pesticide Ltd. (Habin City, China). Funneliformis mosseae (mycorrhizal fungi) was maintained in sand or soil as hyphal segments or a spore mixture, with as pore content program of inoculums of approximately 30, by the Study on Ecological Restoration of Heilongjiang University. The Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences provided the seeds for the host plant M.sativa.

Medicago sativa seeds were rinsed in distilled water two or three times, and then we surface sterilized the seeds with 10% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 10 min and laid the seeds flat on a sheet containing moist double layers of gauze for 24 h. We selected the long white seeds for potting in the culturing system (Fig. 10). The system consisted of 10 growth chambers (PVC tube; diameter = 4.5 cm, depth = 15 cm) and a fixed, blank part outside the growth chamber (PVC tube; diameter = 35 cm, height = 20 cm). Before experimentation, we sterilized the surface with 0.3% potassium permanganate. The soil was composed of a mixture of peat, vermiculite, and sand (5:3:2 mix) and was passed through a 10-mesh sieve, sterilized at 121 °C for 2 h, and treated with 5% sterilization agent. Samples were divided into two groups: an AM group that contained F. mosseae and a CK group that did not. To ensure that M.sativa roots could be separated from the culture medium, we assessed the chamber before planting. We filled the fixed chamber of the culture system with the prepared culture medium, inserted the PVC tubes of the 10 growth chambers into the stroma, and passed distilled water through the soil to confirm stability. Finally, we evenly distributed 50 germinated seeds into each growth chamber and covered them with a thin layer of soil. Displaced light at an illumination intensity of 350 μmol m− 2 s− 1 was provided daily, with a continuous illumination of 14 h. Day and night temperatures were 25 °C and 20 °C, respectively, with the relative humidity maintained at 65%.

Sample collection and preparation

Medicago sativa seedlings were grown for 40 days, with plants whose roots had reached the bottom of the culture system removed from the soil and washed with distilled water. We then transferred these seedlings with a similar level of growth to a black glass tank half-filled with Hoagland nutrient solution. We transplanted 15 M.sativa seedling stains into each pot and allowed them to adapt to the new environment for 7 days, with the nutrient solution replaced every 2 days. Next, half of the samples were treated with Hoagland nutrient solution containing 0.5 mg/L atrazine (0.5 CK and 0.5 AM groups) based on previous findings [84], whereas the other half received only Hoagland solution (0 CK and 0 AM groups) for 6 days. The roots were collected at days 2, 4, and 6 post-atrazine stress induction for both groups.

Determination of mycorrhizal colonization rate in M.sativa

To assess the rate of mycorrhizal colonization, we performed acid fuchsin staining as previously described [85]. We randomly selected samples from each group, stained 100 fragments, observed and counted hyphae, and determined the infection rate.

Determination of malondialdehyde content in M.sativa roots

To assess the degree of stress, we examined malondialdehyde (MDA) using the thiobarbituric acid method. Samples were taken during the same growth period and from the same root positions (0.3 g each). We performed the specific method of determining MDA content as previously described [86], with the MDA concentration (μmol/L) based on fresh weight per gram.

Examination of the protective enzyme system in M.sativa roots

To further examine the effect of atrazine stress, we examined polyphenoloxidase (PPO) activity using the catechol method and peroxidase (POD) activity using the guaiacol method [87]. Absorbance was measured at 525 nm and 470 nm, respectively, with one unit (U) of enzyme activity defined as a change of 0.01 OD per minute per gram fresh weight. Catalase (CAT) activity was examined using ultraviolet absorption, with absorbance measured at 240 nm. One unit (U) was defined as a reduction in absorbance of 0.1 perminute [88]. We examined superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity using the nitrogen blue four triazole method [88], with absorbance measured at 560 nm. One unit (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme that inhibited the photochemical reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) by 50% [88].

Determination of atrazine content in nutrient solution and alfalfa tissue

We extracted atrazine from the nutrient solution [89] and plants [90, 91] as previously described with some modifications. A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (D600; Waters Company, Milford, MA, USA) was utilized with a 5 μm hypersilODS2 filter (4.6 mm × 250 mm; Yilite Analytical Instrument Co. Ltd.),with 20 μL of sample load and run at room temperature. The mobile phase was composed of methanol and water (4:1), and a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min was utilized, with a detection wavelength of 220 nm.

Bio concentration and transfer coefficients

We calculated the bio concentration coefficient as follows: bioaccumulation coefficient = atrazine concentration in plants (roots or stems)/atrazine concentration in nutrient solution. We calculated the transfer coefficient as follows: transfer coefficient = plant stem atrazine concentration/plant root atrazine concentration.

M.sativa root protein extraction

After six days of atrazine stress, significant differences in morphology were noted between the experimental groups. In the CK group, 50% of the seedling leaves appeared yellow, whereas in the AM group, leaves were a scattered yellow. Proteins were extracted from root tissues using trichloroacetic acid/acetone precipitation, and SDT cleavage was utilized as previously described [92]. Protein quantification was performed via BCA. Proteins were visualized via 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (constant current of 14 mA for 90 min), with 20 g of protein combined with 5 μL of loading buffer and placed in a boiling water bath for 5 min before loading. Upon completion, we stained the gel with Coomassie brilliant blue to visualize the proteins.

Enzymatic hydrolysis,iTRAQ labelling, and fractionation of M.sativaroot proteins

We performed protein enzymatic hydrolysis as previously described [93]. The obtained peptide segments (100 μg) from each sample were then labelled using iTRAQ reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA).We used an AKTA purifier 100 (GE Life Sciences, Chicago, IL USA), with elution first performed with buffer A (10 ml MKH2PO4 and 25% ACN; pH 3.0) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Elution was performed next with buffer B (10 ml MKH2PO4, 500 m MKCl, and 25% ACN; pH 3.0). We performed this process at 214 nm, with elution fractions collected every 2 min and a total of 10 replicates obtained.

Masss pectrometry and functional annotation of M.sativa root proteins

We performed HPLC using an Easy-nLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) with an auto sample rata increasing flow rate. First, the column was equilibrated using 95% solution A (0.1% formic acid aqueous solution) and then at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. We desalted the samples on an Acclaim PepMap 100 column C18 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; 100 μm × 2 cm) and separated the samples on an Easy-nLC II analytical column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) via elution gradient with solution B (0.1% formic acid acetonitrile aqueous solution). Following chromatography, we performed mass spectrometry using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), a positive ion detection method. The parameters were as follow: apparent ion scanning range of 300–1800 m/z, a first-order resolution of 70,000 at 200 m/z, an AGC target of 3e6, a first-level maximum IT of 10 ms, as can range number of 1, and a dynamic exclusion of 40.0 s. We identified and quantified proteins using Mascot 2.2 and Thermo Proteome Discover version 1.4 software.

Data processing and analysis method

The data were analysed via analysis of variance using the SPSS 20.0 statistical software package (Chicago, IL, USA). We then visualized differentially expressed proteins using Cytoscape software, with values corresponding to node size, and Origin Pro 8.5.1. Values were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Abbreviations

- 2D-DIGE:

-

Difference gel electrophoresis

- 2-DE:

-

Two-dimensional electrophoresis

- ACC:

-

1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylicacid

- AMF:

-

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- COMT:

-

Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase

- COR:

-

Coronamic acid

- GbPOD1:

-

Ginkgo peroxidase gene

- GST:

-

GlutathioneS-transferase

- iTRAQ:

-

Isobaric tags for relative and absolute transcriptome

- LC-MS:

-

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- NBT:

-

Tetrazolium

- PAL-1:

-

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase protein

- PDIL:

-

Protein disulfide isomerase-like protein

- POD:

-

Peroxidase

- PPO:

-

Polyphenoloxidase

- PR:

-

Pathogenesis-related protein

- SNARE:

-

Soluble N-ethyl-male antibody-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- STK:

-

Serine/threonine kinase

- SYP:

-

Syntaxin protein

References

Chen JJ, He YQ, Zu YQ, Li Y. The research Progress in ecological risk and Phyto-remediation of atrazine. Journal of agro-environment. Science. 2010;29:289–93.

Su SQ. Features of atrazine and problems in application. Agrochemicals Research & Application. 2010;14:1–5.

Mao M, Ren L. The transformation and transport of main degradation products of atrazine in soils - a review. Sci Agric Sin. 2009;42:1690–7.

Bohn T, Cocco E, Gourdol L, Guignard C, Hoffmann L. Determination of atrazine and degradation products in Luxembourgish drinking water: origin and fate of potential endocrine-disrupting pesticides. Food Addi Contam. 2011;28:1041–54.

Baranda AB, Barranco A, de Marañón IM. Fast atrazine photodegradation in water by pulsed light technology. Water Res. 2012;46(3):669–78.

Khan JA, He X, Khan HM, Shah NS, Dionysiou DD. Oxidative degradation of atrazine in aqueous solution by UV/H2O2/Fe2+, UV/S2O82-/Fe2+ and UV/HSO5-/Fe2+ processes: a comparative study. Chem Eng J. 2013;218:376–83.

Xiao XX, Shen SC, Liu YH, Bai-Feng MA. Study on solid phase extraction packing of zirconia /polystyrene and determination of herbicides. J Qiq. Univ. 2013;29:13–6.

Chen BB. Study on removal of atrazine in source water by powdered activated carbon at burst pollution accident. Water & Wastewater Engineering. 2007;33:9–13.

Yang MW, Ye F. Research progress in degradation of pesticides by microbes. Plant Prot. 2010;36:26–839.

Wang C, Song F, Kong XS, Li J. Effects of atrazine residues on the diversity of AM Fungi in black soil farmland. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin. 2015;31:174–80.

Guo SX, Chen DM, Liu RJ. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on antioxidant enzyme activity in peony seedlings under salt stress. Acta Horticulturae Sinica. 2010;37:1796–802.

Shen LY, Mao YM, Lu JY, Peng SQ, Li XL, Zhang FS. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizae on salt tolerance of wild jujube (Zizyphus spinosus Hu) seedlings. Acta Pedol Sin. 2004;41:426–33.

Tian Y, Zhang HH, Meng XY, Wang J, Ju-Wei HU, Sun GY. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal Fungi (Glomus mosseae) on growth and photosynthesis characteristics of Lolium perenne L. under cd contaminated soil. Acta Agrestia Sinica. 2013;21:135–41.

Yang YZ. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhiza on tea growth and tea quality under stress. Journal of Green Science and Technology. 2016;7:127–8.

Zhong K, Wang MY, Liu RJ. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: life cycle, genetic characteristics and biological fundamentals of their pure culture. Mycosystema. 2009;28:310–4.

Zhang FS. Rhizosphere Ecology: China Agricultural: University Press; 2009.

Wang L, Wang M, Ma F, Li Z, Wu JT, An GN. The effect of AMF on the promotion and resistance against Fusariumsolani of wheat seeding. Journal of Harbin Institute of Technology. 2015;47:15–9.

Li L, Cai BY. Advances in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alleviating continuous cropping obstacles. Chin J Ecol. 2016;35:1372–7.

Huang H, Zhang S, Shan XQ, Chen BD, Zhu YG, Bell JN. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus (Glomus caledonium) on the accumulation and metabolism of atrazine in maize (Zea mays L.) and atrazine dissipation in soil. Environ Pollut. 2007;146:452–7.

Huang H, Zhang S, Wu N, Lei L, Peter C. Influence of Glomus etunicatum/Zea mays mycorrhiza on atrazine degradation, soil phosphatase and dehydrogenase activities, and soil microbial community structure. Soil Biol Biochem. 2009;41:726–34.

Song FQ, Ding ML, Dong AR, Fan XX, Zhao XJ. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) Fungi on atrazine degradation in soil planted Sorghum. J Soil Water Conserv. 2010;24:189–93.

Song FQ, Li J, Fan XX, Zhang Q, Chang W, Yang F, Geng G. Transcriptome analysis of Glomus mosseae/Medicago sativa mycorrhiza on atrazine stress. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20245.

Yu MD. Studies on degradation characteristics of atrazine in soil by symbiosis of AM fungi and alfalfa. Heilongjiang University. 2015.

Chen XF, He XH, Ye SH, Song S, Yang M, Wang YY, et al. ITRAQ technology and its research advances in animal proteomics. Heilongjiang Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine. 2016;7:57–60.

Jin CX, Guo Y, Liu JJ. Physiological and Biochemical changes in wheat seedlings under Sulfamonomethoxine stress. Journal of agro-environment Science. 2014;33:634–9.

Qin FM, Zhang HX, Wu W, Zhou DW. Effect of salt stress on germination and seedling growth of alfalfa. Acta Prataculturae Sinica. 2010;19:71–8.

Cai PY. Effect of different herbicides on weeds in alfalfa field and the safety and physiological indexes of alfalfa seedling stage. Gansu Agricultural University. 2016.

Wu YJ, He GQ, Shi YR, Liang ZS. Changes of relative water content, proline and malondialdehyde content in Vicia faba leaves treated with different pH buffer solution. Study on Agriculture in Arid areas. 2009;27:169–72.

Li C, Wen HF, Zhen RL, Chen J, Ma XJ, Wang QH. Phytotoxicity of atrazine to Acorus calamus L. Journal of Agro-Environment Science. 2016;35:1895–902.

He J, He X, Gao YT, Wang B, Zhou YB. The influence of oil concentration in soil on growth and physiological characteristics of Suaeda heteroptera. Journal of agro-environment Science. 2011;30:650–5.

Sun YF, Song FQ, Chang W, Fang XX. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal Fungi on growth and physiology of Elaeagnus angustifolia seedlings subjected to salinity stress. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 2016;52:18–27.

Ruizlozano JM, Porcel R, Azcón C, Aroca R. Regulation by arbuscular mycorrhizae of the integrated physiological response to salinity in plants: new challenges in physiological and molecular studies. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:4033–44.

Zhu XC, Song FB. Signaling and genes in arbuscular mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Life Science Research. 2008;12:95–9.

Eskandari S, Guppy CN, Knox OGG, Flavel RJ, Backhouse D, Haling RE. Mycorrhizal contribution to phosphorus nutrition of cotton in low and highly sodic soils using dual isotope labelling (32P and 33P). Soil Biol Biochem. 2017;105:37–44.

Wu CX, Wu XH, Zhang XF, Liu B, Liu JL. A review on cytochrome P450s and metabolisms of herbicides. Agrochemicals Research & Application. 2008;6:8–12.

Edwards R, Dixon DP, Cummins I, Brazierhicks M, Skipsey M. New perspectives on the metabolism and detoxification of synthetic compounds in plants. Netherlands: Springer; 2011.

Inui H, Ueyama Y, Shiota N, Ohkawa Y, Ohkawa H. Herbicide metabolism and cross-tolerance in transgenic potato plants expressing human CYP1A1. Pesticide Biochemistry & Physiology. 1999;64:33–46.

Nafisi M, Goregaoker S, Botanga CJ, Glawischnig E, Olsen CE, Halkier BA, Glazebrook J. Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 monooxygenase 71A13 catalyzes the conversion of Indole-3-Acetaldoxime in Camalexin synthesis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2039–52.

Lu YC, Yang SN, Zhang JJ. A collection ofglycosyltransferases from rice (Oryza sativa) exposed to atrazine. Gene. 2013;531:243–52.

Kawahigashi H. Transgenic plants for phytoremediation of herbicides. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:225–30.

Jones P, Vogt T. Glycosyltransferases in secondary plant metabolism: tranquilizers and stimulant controllers. Planta. 2001;213:164–74.

Peer WA. Arabidopsis AtGSTF2 is regulated by ethylene and auxin, and encodes a glutathione S-transferase that interacts with flavonoids. Plant J. 2003;36:433–42.

Guo YL, Tao B, Zheng TJ, Li BY, Zhuo XH, Pan YQ. Inducement action of plant GSTs andherbicides antidotes. J Northeast Agric Univ. 2008;39:136–9.

Zhou ZX, Chang W, Jia TT, Fan XX, Li JZ, Song FQ. Effect of Alfalfa Mycorrhiza on Atrazine Degradation and Enzyme Activities in Soil 2016;32:182–187.

Li JZ. Analysis of alfalfa mycorrhiza transcriptional group under atrazine stress. Heilongjiang University. 2015.

Lu YC. Cloning and Phylogenetic analysis of laccase gene from maize and ryegrass and study on gene expression under water stress in maize. Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. 2004.

Lavid N, Tel-Or E. The involvement of polyphenols and peroxidase activities in heavy-metal accumulation by epidermal glands of the waterlily (Nymphaeaceae). Planta. 2001;212:323–31.

Wang GD. Phytoremediation of phenolic acids and trichlorophenol in Arabidopsis thaliana with overexpression of laccase of cotton in vitro. Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of sciences (Shanghai institute of Life Sci). 2004.

Amaya I, Botella LCM, Medina M, Heredia A, Bressan R, Hasegawa P, et al. Improved germination under osmotic stress of tobacco plants over expressing a cell wall peroxidase. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:80–4.

Cheng H, Li LL, Wang Y, Cheng SY. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of POD1 gene from Ginkgo biloba L. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Sinica. 2010;25:44–51.

Zhao HK, Li QY, Wang YM, Zhuang BC. The prongress of the syudies on soybean kunitz trypsin inhibitor. Soybean Science. 2002;21:218–22.

Wang W, Zhu Z, Gao YF, Shi CL, Chen WX, Guo ZC, et al. Obtaining a transgenic upland cotton harboring two insecticidal genes. Acta Bot Sin. 1999;41:384–8.

Wamaedeesa, Raheema. Molecular aspects of 2OG-Fe(II)-dioxygenases and response to abiotic stress in rice 2016.

Chou ZH. Differential proteomics analysis of Zaoshu pear and its red budding fruit. Northwest A&F University. 2014.

Sánchezaguayo I, Rodríguezgalán JM, García R, Torreblanca J, Pardo JM. Salt stress enhances xylem development and expression of S -adenosyl- l -methionine synthase in lignifying tissues of tomato plants. Planta. 2004;220:278–85.

Team. Effect of birch (Betula spp.) and associated rhizoidal bacteria on the degradation of soil polyaromatic hydrocarbons, PAH-induced changes in birch proteome and bacterial community. Environ Pollut. 2009;157:341–6.

Yu S, Du J, Le Y, Zhan X. Proteomic analysis of plasma membrane proteins in wheat roots exposed to phenanthrene. Environmental Science & Pollution Research International. 2016;23:10863–71.

Liu X. Analysis of differentially expressed genes in mycorrhiza of Amorpha fruticosa by transcriptome sequencing. Heilongjiang University. 2016.

Wang J, Hong YX, Cai QQ, Li QL, Wang SY, Rao PF. Isolation and Characterization of a novel lectin WKBL from Phaseolus lunatus Linn. Chinese Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2012;28:637–44.

Li D, Li J. Antifungal activity of a recombinant defensin CADEF1 produced by Escherichia coli. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology. 2009;25:1911–8.

Yu J, Liu CY, Zhao AC, Wang CH, Cai YX, Yu MD. Functional analysis of 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase Gene's promoter in mulberry. Acta Agron Sin. 2017;43:839–48.

Dong MC, Yang X, Zhang ZC, Li YF, Guan RZ. Identification and Expression analysis of 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase gene from Quinclorac-resistant Barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli). Sci Agric Sin. 2015;48:4077–85.

Yao C, Conway WS, Ren R, Smith D, Ross GS, Sams CE. Gene encoding polygalacturonase inhibitor in apple fruit is developmentally regulated and activated by wounding and fungal infection. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;39:1231–41.

Cao WL. Role of SNARE protein gene OsSYP121 in rice blast resistance. Agricultural University of Nanjing. 2014.

Assaad FF, Huet Y, Mayer U, Jürgens G. The cytokinesis gene KEULE encodes a Sec1 protein that binds the Syntaxin Knolle. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(3):531–44.

Rolfe BG. Proteomic analysis of somatic embryogenesis in Medicago truncatula. Explant cultures grown under 6-Benzylaminopurine and 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid treatments. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:1250–60.

Colditz F, Nyamsuren O, Niehaus K, Eubel H, Braun HP, Krajinski F. Proteomic approach: identification of Medicago truncatula proteins induced in roots after infection with the pathogenic oomycete Aphanomyces euteiches. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;55:109–20.

Dassi B, Dumas-Gaudot E, Gianinazzi S. Do pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins play a role in bioprotection of mycorrhizal tomato roots towards Phytophthora parasitica ? Physiological & Molecular Plant Pathology. 1998;52:380–3.

Repetto O, Bestelcorre G, Dumasgaudot E, Berta G, Gianinazzipearson V, Gianinazzi S. Targeted proteomics to identify cadmium-induced protein modifications in Glomus mosseae-inoculated pea roots. New Phytol. 2003;157:555–67.

Guo GY, Bai F, Liu W, Mi CL. Advances in research of the regulation of transcription factors of lignin biosynthesis. Sci Agric Sin. 2015;48:1277–87.

Liu Y, Xiao R, Yang DH, Liu X, Li QW. The Progress of the biological functions of cysteine-rich secretory proteins. Chinese Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;3:367–73.

Chien PS, Hong GN, Chen YR. A salt-regulated peptide derived from the CAP superfamily protein negatively regulates salt-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:5301–13.

Zhou YY. Regulation effect and physiological mechanism of corcrowin on wheat heat resistance. China Agriculture University. 2013.

Janiszewski M, Lopes LR, Carmo AO, Pedro MA, Brandes RP, Santos CX, et al. Regulation of NAD(P)H oxidase by associated protein disulfide isomerase in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40813–9.

He HB, Jia GX. Research Progress in early symbiotic signal transduction in legumes. Chinese Bulletin of Botany. 2013;48:665–75.

Denancé N, Szurek B, Noël LD. Emerging functions of Nodulin-like proteins in non-Nodulating plant species. Plant & Cell Physiology. 2014;55:469–74.

Garrochovillegas V, Gopalasubramaniam SK, Arredondopeter R. Plant hemoglobins: what we know six decades after their discovery. Gene. 2007;398:78–85.

Shen SH, Jing YX. Present situation and Prospect of biological nitrogen fixation in China. Chin Sci Bull. 2003;48:535–40.

Wang XQ, Yang PF, Liu Z, Liu WZ, Hu Y, Chen H, et al. Exploring the mechanism of Physcomitrella patens desiccation tolerance through a proteomic strategy. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1739–50.

Chen LR, Markhart AH, Shanmugasundaram S, Lin TY. Early developmental and stress responsive ESTs from mungbean, Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek, seedlings. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:535–52.

Burian J, Ramón-García S, Howes CG, Thompson CJ. WhiB7. A transcriptional activator that coordinates physiology with intrinsic drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2012;10:1037–47.

Xiao ZW, Fu YF. Research Progress in AT-hook proteins. J Agric Sci Technol. 2009;11:12–6.

Zhang GW, Zeng Y, Guo W, Luo Q. Bioinformatics analysis of the AT-hook gene family in Rice. Chinese Bulletin of Botany. 2014;49:49–62.

Wang L, Samac DA, Shapir N. Biodegradation of atrazine in transgenic plants expressing a modified bacterial atrazine chlorohydrolase (atzA) gene. Plant Biotechnol J. 2005;3:475–86.

Phillips JM, Hayman DS. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1970;55(1):158 IN116–161,IN118.

Fan JJ, Yuan YY. An experimental course in plant physiology. China agricultural: University Press; 2015.

Yuan QH, Gui Z, Zhang WS. Comparison of the activities of SOD,POD and PPO within alfalfa cultivarsresistant and susceptible to alfalfa common leaf. Acta Pratacultural Science. 2002;11:100–4.

Zhang ZA, Zhang MS, Wei RH. Experimental guidance of plant physiology in teaching materials of agricultural colleges and universities. In: China agricultural science and technology press; 2004.

Li JF, Gao DW, Zhou BR. Determ ination ofAtrazine inW ater using EthylAcetate extraction-H igh performance liquid chromatography method. Forest Engineering. 2010;26:12–4.

Qu MJ, Li HD, Li N, Zhang M, Zhu DW. The influence of submersed macrophytes on the migration of atrazine in water. Journal of agro-environment Science. 2016;35:750–6.

Luo MF, Tan JP, Chen Z. Determination of Carbendazim and atrazine in sugar cane juice by high performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Shunde Polytechnic. 2014;4:10–2.

Alvarez S, Hicks LM, Pandey S. ABA-dependent and -independent G-protein signaling in Arabidopsis roots revealed through an iTRAQ proteomics approach. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:3107–22.

JR W, Zougman A, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:359–62.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Company for the help with iTRAQ sequencing. We also thank Springer Nature for providing linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript. Moreover, we thank Tong Zhang for preparing the manuscript.

Funding

The National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31570635, 31500431 and 31270535) and Outstanding Youth Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (JC201306) supported this work.

Availability of data and materials

The relevant experimental material and proteomic data are preserved in the Ecological Restoration lab of Heilongjiang University. The CAT, MDA, POD, PPO, PROLINE and SOD data are submitted as a supplement file.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XS and QW contributed equally for this article. XS and QW did the experiment and analyzed data and wrote this paper. WC participated to analyze the data. XF participated to do this experiment. FS designed this experiment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Approval to publish.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sui, X., Wu, Q., Chang, W. et al. Proteomic analysis of the response of Funnelifor mismosseae/Medicago sativa to atrazine stress. BMC Plant Biol 18, 289 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1492-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1492-1