Abstract

Background

Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) causes severe community acquired infections, predominantly in Asia. Though initially isolated from liver abscesses, they are now prevalent among invasive infections such as bacteraemia. There have been no studies reported till date on the prevalence and characterisation of hvKp in India. The objective of this study is to characterise the hypervirulent strains isolated from bacteraemic patients for determination of various virulence genes and resistance genes and also to investigate the difference between healthcare associated and community acquired hvKp with respect to clinical profile, antibiogram, clinical outcome and molecular epidemiology.

Results

Seven isolates that were susceptible to all of the first and second line antimicrobials and phenotypically identified by positive string test were included in the study. They were then confirmed genotypically by presence of rmpA and rmpA2 by PCR. Among the study isolates, four were from patients with healthcare associated infections; none were fatal. All patients with community acquired infection possessed chronic liver disease with fatal outcome. Genes encoding for siderophores such as aerobactin, enterobactin, yersiniabactin, allantoin metabolism and iron uptake were identified by whole genome sequencing. Five isolates belonged to K1 capsular type including one K. quasipneumoniae. None belonged to K2 capsular type. Four isolates belonged to the international clone ST23 among which three were health-care associated and possessed increased virulence genes. Two novel sequence types were identified in the study; K. pneumoniae belonging to ST2319 and K. quasipneumoniae belonging to ST2320. Seventh isolate belonged to ST420.

Conclusion

This is the first report on whole genome analysis of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae from India. The novel sequence types described in this study indicate that these strains are evolving and hvKp is now spread across various clonal types. Studies to monitor the prevalence of hvKp is needed since there is a potential for the community acquired isolates to develop multidrug resistance in hospital environment and may pose a major challenge for clinical management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a common cause of nosocomial and community acquired infections especially in immunocompromised patients. K. pneumoniae is categorised into three phylogenetic groups: KpI, KpII and KpIII. KpI comprises of K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis and K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae. Recently, KpII has been designated as K. quasipneumoniae and was further classified into KpIIa which is K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae and KpIIb which is K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae [1]. The KpIII group comprises of K. variicola. Accurate phenotypic identification of these species is difficult and can be achieved by molecular techniques [1].

K. pneumoniae which is commonly associated with urinary tract infection, pneumonia, bacteraemia and wound infections, is also a primary causative agent of liver abscess particularly in Asia. The strains causing liver abscess are mostly community acquired and associated with a hypermucoid phenotype. These hypermucoviscous types, also called as hypervirulent (hv) K. pneumoniae (Kp) are often susceptible to antimicrobials [2]. They have the potential for metastatic spread in young and healthy individuals without a history of hepatobiliary disease [2]. In 2016, Breurec et al. reported K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae with hypervirulent characters causing liver abscess [3]. Molecular identification of these strains is by the detection of rmpA, rmpA2 and magA genes by PCR. rmpA and rmpA2 are the regulators of mucoid phenotype; rmpA2 shares 80% identity with 3’ DNA sequences of rmpA [4]. magA, codes for the K1 mucoviscous serotype. Though these markers are described, hypervirulent K. pneumoniae has no internationally agreed definition and different terms have been used by investigators. Some authors define hypervirulence by the presence of a mucoid phenotype whilst others define based on the detection of rmpA and rmpA2. Recently iutA gene encoding aerobactin has been used to define hvKp [5]. Other authors have considered virulence factors such as siderophores, type3 fimbriae and allantoin metabolism [6].

The objective of this study is to characterise the hypervirulent strains isolated from bacteraemic patients for (i) determination of various virulence genes and resistance genes, (ii) to investigate the difference between healthcare associated and community acquired hvKp isolates with respect to clinical profile, antibiogram, clinical outcome and molecular epidemiology.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

K. pneumoniae isolates from bacteremic patients during 2015 were collected at the department of Clinical Microbiology, Christian Medical College, India. The isolates were speciated using standard culture, biochemical and identification procedures [7]. String test was used to identify the hypervirulent phenotype. It was defined as positive if there was formation of mucous string of >5 mm when the bacterial colony was stretched, with an inoculation loop [2]. During the study period, twenty seven isolates were positive for string test. Among which, seven isolates with well-defined criteria for hypervirulence based on PCR positive for virulence genes rmpA and rmpA2 and representative of community and hospital acquired bacteremia were chosen for further characterization. In this study, hypervirulent strains are defined as those that are string test positive and carry both rmpA and rmpA2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method for the commonly used antimicrobials as described by CLSI [8]. The panel of antimicrobials tested includes ceftazidime (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), amikacin (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg) and tigecycline (15 μg). E. coli ATCC 25922 was the control strain used for susceptibility testing. The results were interpreted according to CLSI 2015 guidelines [9]. For tigecycline, interpretation was according to FDA criteria (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/021821s016lbl.pdf).

Molecular characterisation of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae

PCR for rmpA, rmpA2 and capsule types 1&2

String test positive isolates were then subjected to conventional PCR for rmpA, rmpA2, magA and K2 genes as described in previous studies [10, 11]. magA is used to identify K1 capsular type and K2wzy is for the K2 capsular type.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) for hv K. pneumoniae

The seven isolates that were positive for rmpA, rmpA2 and susceptible to all the antimicrobials tested, were subjected to whole genome sequencing. DNA was extracted using Qiasymphony (Qiagen) as per manufacturer’s instructions. The whole genome sequencing was done with Ion Torrent PGM platform using 400 bp read chemistry as described in our previous report [12]. Raw reads were assembled de novo using Assembler SPAdes software v5.0 in Torrent suite server version 4.4.3. Coverage of the genomes ranged from 6.5X to 87.6X for the seven isolates. Annotation of the genomes was performed with RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystems Technology- http://rast.nmpdr.org/) and PATRIC (Pathosystems Resource Integration Centre - https://www.patricbrc.org/). The whole genomes shotgun sequences were deposited at GenBank to obtain accession numbers.

The annotated whole genome sequences (WGS) were used for the prediction of antibiotic resistance genes, plasmids and the sequence type from the ResFinder, PlasmidFinder and MLST finder tool, respectively, of the Centre for Genomic Epidemiology (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/). The list of alleles for the virulence genes of K. pneumoniae was provided by the Pasteur Institute and was screened from the WGS data accordingly (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/perl/bigsdb/bigsdb.pl?db=pubmlst_klebsiella_seqdef_public&page=profiles).

The relatedness of the predicted sequence types were investigated by eBURST V3 software employing the BURST algorithm. Genetic relatedness and comparative genomic analysis of the isolates were performed using EDGAR software (https://edgar.computational.bio.uni-giessen.de/cgi-bin/edgar_login.cgi).

Demographic and clinical details of the patients

The demographic and clinical details of the patients including age, sex, source of infection, co-morbidities and 30 day outcome were obtained from electronic medical records of the hospital. Healthcare associated infection was defined as blood culture positive in the first 48 h of admission in a patient hospitalized for at least two days within the last 90 days, receiving specific home nursing care or attending hospital or haemodialysis clinic in the 30 days before infection. Community acquired infection was defined as blood culture positive within 48 h of admission in a patient without prior hospitalization in last 90 days.

Results

The clinical details of the seven patients are summarised in Table 1. The patients aged from 29 years to 88 years with median age of 55 years. Five of the seven patients were male. All patients had a co-morbid condition. Three patients had intra-abdominal infection but none had liver abscess or metastatic infection. At 30 days three patients expired. Three isolates were from patients with community acquired infection while four were from patients with healthcare associated infections. All three patients with community acquired infection had chronic liver disease and expired. The four patients with hospital acquired infection had no chronic liver disease and all survived.

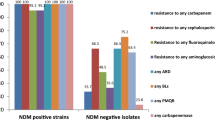

The seven isolates were susceptible to all the antimicrobials tested. The isolate Kp3 was resistant to ciprofloxacin. Though the isolates were phenotypically susceptible to all tested antimicrobials, six harboured oqxA and oqxB genes coding for fluoroquinolone resistance. blaSHV gene is intrinsic to K. pneumoniae and the variants blaSHV-36 and blaSHV-75 were detected in the study isolates. As per annotation from NCBI, one isolate was found to be K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae and belonged to K1 capsular type. K. quasipneumoniae carried the blaOPKB-2 gene which is inherently present in this species and can serve as a marker for identification (Breurec et al., 2016).

Results of PCR for magA (K1) and K2wzy genes are summarised in Table 2 along with the accession number of the genomes. Molecular determination of capsule revealed four isolates belonged to K1 capsular type indicated by the presence of magA gene. Three isolates did not belong to K1 or K2 capsular types by PCR. However, from the whole genome sequence analysis, Kp1 and Kp5 were found to belong to K20 and K1 respectively. Isolate Kp6 was untyped in the study.

The whole genome sequences were analysed for virulence genes and are listed in Table 2. Ferric iron uptake was encoded by genes including kfuA, kfuB and kfuC (ferric iron ABC transporter). The fyuA gene, which encodes an outer membrane receptor for ferric siderophores, was also present. Allantoin metabolism was controlled by genes allB (allantoinase), allR (negative regulator), allS (transcriptional activator) and ybbW (allantoin permease). Genes encoding enterobactin identified in the study isolates were entB (isochromatase) and entF (enterobactin synthetase component). Salmochelin, a derivative of enterobactin, was encoded by iroB (glycosyltransferase), iroC (ABC transporter protein) and iroN (outer membrane siderophore receptor). Genes coding for aerobactin identified in the study were iutA (aerobactin siderophores receptor), iucA (N(2)-citryl-N(6)-acetyl-N(6)-hydroxylysine synthase), iucB (N6-hydroxylysine O-acetyltransferase), iucC (Aerobactin synthase) and iucD (L-lysine 6-monooxygenase). Yersiniabactin encoding genes identified in the genomes were irp1 (polyketide synthetase), irp2 (iron acquisition yersiniabactin synthesis enzyme), ybtA (iron acquisition regulator), ybtE (2,3-dihydrobenzoate-AMP ligase), ybtP (putative inner membrane ABC transporter), ybtQ (putative ABC iron siderophore transporter), ybtT (yersiniabactin synthesis enzyme) and ybtU (thiazolinyl imide reductase).

The whole genome analysis revealed the presence of plasmids in all seven isolates. All isolates harboured the plasmid IncHI1B but did not carry any resistance genes. IncR and IncFIB were found in one isolate each. Six isolates harboured the plasmid pLVKP which is characteristically associated with hypervirulent strains. The plasmid is known to contain rmpA, rmpA2 and iutA genes. This plasmid could not be located in Kp2, although it contained the rmpA and rmpA2 genes, which can be attributed to missing sequences during the contig arrangement of the raw reads in Ion Torrent. All the isolates harboured mrkD which aids in biofilm formation. All the K. pneumoniae isolates coded for genes responsible for allantoin metabolism which the K. quasipneumoniae lacked.

Among the various sequence types seen, magA gene (K1 capsular type) was seen among the isolates belonging to ST23 which is characteristic to this clonal type. One isolate belonged to ST420 and two isolates had novel sequence types namely ST2319 and ST2320. The novel sequence types submitted to Institut Pasteur MLST system (Paris, France) and were assigned new sequence types. K. quasipneumoniae belonged to the novel sequence type ST2320 and K1 capsular type.

eBURST analysis of the seven isolates is shown in Fig. 1. The sequence types seen in the study isolates form separate clusters as shown. However, ST2319 which is a newly assigned clonal type is a single locus variant of ST420. The two STs differ in the tonB allele with ST420 having tonB-36 and ST2319 having tonB-176. Hence these two clonal types are closely related.

Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic tree of the study isolates which was constructed using EDGAR software with three reference genomes namely K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae NTUH K2044 NC 012731, K. pneumoniae KP1 NZ CP012883 and K. quasipneumoniae ATCC 700603 CP014696. The K. quasipneumoniae isolate in the present study is related to the K. quasipneumoniae ATCC700603 isolate. Other isolates such as Kp2, Kp3, Kp4 and Kp5 are closely related to the reference genomes used while KP1 and Kp6 stand out as separate groups. From Fig. 2, the result of phylogenetic tree shows that the ST23 are closely related while the ST420 and ST2319 are more diverse.

Phylogenetic tree of the hypervirulent K. pneumoniae. The phylogenetic tree for 10 genomes built out of a core of 2999 genes per genome and 29,990 in total. The core has 958,416 AA-residues/bp per genome, 9,584,160 in total. Each entry is represented by isolate name followed by sequence type and type of infection. HAI: Healthcare associated infection, CAI: Community acquired infection, ST: Sequence type

Figure 3a depicts the comparative Venn diagram for the four healthcare associated hypervirulent isolates showing the genes shared by them. Kp3 and Kp5 have 181 and 813 genes respectively exclusive to the isolates and share a lot of genes with other two genomes. Figure 3b is the venn diagram of the three community acquired hypervirulent isolates. Kp6 has 4220genes exclusive to the isolate and the community acquired isolates share lesser genes among themselves than the healthcare acquired isolates. K. quasipneumoniae is a smaller genome when compared to the K. pneumoniae isolates.

a: Venn diagram of the four healthcare associated hypervirulent K. pneumoniae isolates. Isolate1: Kp3, isolate2: Kp2, isolate3: Kp1 and isolate4: Kp5. Kp3 and Kp5 have 181 and 813 genes respectively exclusive to the isolates and share a lot of genes with other two genomes. b: Venn diagram of community acquired K. pneumonia and K. quasipneumoniae isolates. Isolate1: Kp6, isolate2: Kp4 and isolate3: Kqp. Kp6 has 4220genes exclusive to the isolate and the community acquired isolates share lesser genes among themselves than the healthcare acquired isolates. K. quasipneumoniae is a smaller genome when compared to the K. pneumoniae isolates

Discussion

This case series is the first report from India characterizing hvKp isolates from bacteremia using WGS. There have been genome announcements of hypervirulent strains [13,14,15] but there have been no reports from India on molecular analysis of the same enumerating the virulence genes. Most studies describe hvKp in isolates from liver abscesses; studies on hvKp from patients with bacteraemia are limited and lacking from the Indian setting. Seven susceptible isolates were chosen for characterisation since classically hvKp were susceptible to all antimicrobials. They have been associated more with community acquired infections such as liver abscess than healthcare associated infections. Interestingly, all three patients with community acquired infection in this study had underlying liver disease and succumbed to infection. This may be due to late presentation to hospital when these patients were critically ill. Community acquired hvKp infections are often associated with high mortality rates [2]. In contrast, no patients with hospital acquired infection had underlying liver disease and all survived.

Though the isolates harboured β-lactamase genes such as bla SHV-36 and bla SHV-75 , they were phenotypically susceptible to β-lactam antibiotics. bla SHV contributes to the intrinsic resistance to ampicillin in K. pneumoniae [16]. Genes encoding resistance to fluoroquinolones such oqxA and oqxB were present in all but only one strain was found resistant to ciprofloxacin by disc diffusion. All the isolates harboured the IncHI1B type of plasmid. However, there was no resistance gene found associated with this plasmid. The hvKp strains have been characteristically susceptible to antibiotics although recent reports suggest the emergence of MDR-hvKp [17,18,19].

K. pneumoniae has several virulence factors which includes the ability to produce siderophores, such as aerobactin, enterobactin and yersiniabactin, genes involved in ferric iron uptake, allantoin metabolism and biofilm formation [2]. Strains of K. pneumoniae capable of over-producing siderophores are considered to be hypervirulent [20, 21]. The strains which do not secrete siderophores have decreased virulence and hence are less efficient at infection and colonization. Sah et al., demonstrated that siderophores are important for pathogenic K. pneumoniae to survive in low iron concentration [22]. Pomakova et al., showed that hvKp was able to survive longer in rat abscess model as well as in 90% human serum than the classical Kp strains [23]. The hypermucoviscous nature and added virulence factors contribute to the increased severity of infections caused by hvKp, despite susceptibility to first and second line antibiotics.

The hvKp in this study was defined based on the clinical features, positivity to string test and presence of rmpA and rmpA2. Seven isolates were chosen for WGS by Ion Torrent to characterise the virulence genes. The plasmid pLVPK (Large Virulence Plasmid of K. pneumoniae) was identified. This plasmid harbours the rmpA, rmpA2 genes and also the multiple iron acquisition systems iucABCDiutA and iroBCDN siderophore gene clusters [24]. These genes were identified in the isolates harbouring the pLVPK in this study. An in vivo study in a mouse model shows the absence of dissemination of hvKp from liver abscess when there is loss of pLVPK [25]. Jung et al., also observed the presence of rmpA2 in all the rmpA positive isolates similar to our study findings [21].

Several genes coding for aerobactin, yersiniabactin and their receptors were present in all the seven study isolates as listed in Table 2. A previous report by Hsieh et al., reports that these siderophores were more frequent in hvKp strains than the cKp strains [26]. Jung and colleagues in Korea reported the presence of aerobactin gene in all the study isolates and the gene for allantoin metabolism, allS, was present in 50% of the hvKp isolates [21]. Aerobactin enables the survival of hvKp in vivo and ex vivo and plays a significant role than the other siderophores such as enterobactin and yersiniabactin [27]. ybtQ, coding for a transporter for yersiniabactin was present in K. quasipneumoniae. This has been demonstrated to have an important role for the survival of K. pneumoniae in iron limiting condition [28].

Genes for allantoin metabolism were present in 57% of the study isolates comparable to the findings by Jung et al. [21]. The genes rmpA, rmpA2, aerobactin and allS were found frequently in hvKp isolates than the classical Kp (cKp) isolates from bacteremia [21]. All the isolates in this study harboured mrkD which is an adhesin and aids attachment to acellular surfaces. One isolate each showed the presence of mrkB, chaperone, and mrkC, an outer membrane usher gene [29]. These genes are essential in pili formation and are important for biofilm formation and colonisation. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to report the presence of mrkB and mrkC. All the isolates had the gene MviM which is a virulence factor but the significance has not been described till date.

Microcins are low molecular weight antimicrobial peptides produced by Enterobacteriaceae against other gram negative bacteria. In one isolate, mceC and mceD genes were identified. mceC is involved in the maturation of microcin while the function of mceD has not been defined [30].

When investigating isolates from patients with liver abscess, Yu et al. found the hypermucoviscous phenotype, rmpA, aerobactin, kfu and allS were present in 96%, 100%, 100%, 100%, and 100% respectively of K1 type isolates; whereas in nonK1/K2 isolates, they were present in 79%, 86%, 93%, 50% and 0% respectively [31]. This highlights the association between virulence genes and capsular type in hvKp. In the present study, four isolates of K1 type had a similar virulence gene profile while the K. quasipneumoniae, although of K1 type, lacked genes for iron uptake and allantoin metabolism. This can also be attributed to clonal types of the isolates. Four isolates of K1 capsular type belonged to ST23. Kp6 belonging to ST2319 is closely related to ST420 are shown in Fig. 1 and both do not belong to capsular type K1 or K2. K. quasipneumoniae belonging to K1 capsular type and ST2320 is an outgroup.

HvKp are frequently associated with ST23 and capsular types K1 or K2 [32, 33]. In this study, four isolates belonged to ST23, all of which were K1 type. Kp1 belonged to K20 which is also associated with hvKp [2] and Kp6 was untyped. The isolates belonging to ST23 had a similar virulence profile. The isolate belonging to ST420 differed from the isolates belonging to ST23 in lacking genes for allantoin metabolism. Similar result was observed with novel types ST2319 and ST2320. The presence of large number of virulence genes could explain the high pathogenicity reported in ST23 isolates than the other clonal types. The presence of the international circulating clone in India may threaten the management of infections with MDR K. pneumoniae. ST420 with rmpA has previously been reported in a patient with a liver abscess; similar to the isolate in this study patient [34]. Three patients with hospital acquired infection had ST23; these patients were on different wards at different times which suggest that this was not part of an outbreak. Community acquired hvKp infections of ST23 have been commonly reported but here ST23 is associated with hospital infection. Hence containment of hvKp infections is essential which requires monitoring the incidence of these infections. One of the two new sequence types, ST2319 is a variant of ST420 differing in the tonB allele. This indicates the emergence of strains with new sequence types and virulence characteristics.

Conclusion

The concerns of hvKp include its prevalence among bacteraemic isolates without the presence of liver abscess. The hypervirulent strains are now being reported not only among K. pneumoniae but also among K. quasipneumoniae. To date, predominant sequence types associated with hvKp include ST23 and ST57. Here we report new clonal types among hvKp, ST2319 and ST2320, which indicates that these strains are spreading and no longer restricted to selected clonal groups. This is of concern as these strains confer more severe disease with higher mortality rates. It is also concerning that four out of seven of our isolates were from patients with healthcare associated infection whereas previously hvKP has been seen mainly in the community. The community acquired strains as in the present study lead to fatal outcome unlike nosocomial strains. Also, there is potential for the community acquired hypervirulent isolates to develop multidrug resistance in the hospital environment and may become difficult to manage. Further studies are required to monitor their occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility profile. Also, there is urgent need to establish an international definition and definitive identification markers for hypervirulent K. pneumoniae.

Abbreviations

- allB :

-

allantoinase

- allR :

-

negative regulator for allantoinase

- allS :

-

transcriptional activator

- ATCC:

-

American Type Culture Collection

- CLSI:

-

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute

- entF :

-

enterobactin synthetase component

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- hvKp:

-

hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Inc.:

-

Incompatible

- iroB :

-

glycosyltransferase

- iroC :

-

ABC transporter protein

- iroN :

-

outer membrane siderophore receptor

- irp1 :

-

polyketide synthetase

- irp2 :

-

iron acquisition yersiniabactin synthesis enzyme

- iucA :

-

N(2)-citryl-N(6)-acetyl-N(6)-hydroxylysine synthase

- iucB :

-

N6-hydroxylysine O-acetyltransferase

- iucC :

-

Aerobactin synthase

- iucD :

-

L-lysine 6-monooxygenase

- iutA :

-

aerobactin siderophores receptor

- Kp:

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Kqp:

-

Klebsiella quasipneumoniae

- magA :

-

mucoviscosity associated gene

- mce :

-

Microcin

- mrkD :

-

type 3 fimbriae

- PATRIC:

-

Pathosystems Resource Integration Centre

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- pLVKP:

-

Large Virulence plasmid of Klebsiella pneumoniae

- RAST:

-

Rapid Annotation using Subsystems Technology

- rmpA :

-

regulator of mucoid phenotype

- ST:

-

Sequence type

- WGS:

-

Whole genome sequencing

- ybbW :

-

allantoin permease

- Ybt:

-

Yersiniabactin

- ybtA :

-

iron acquisition regulator

- ybtE :

-

2,3-dihydrobenzoate-AMP ligase

- ybtP :

-

putative inner membrane ABC transporter

- ybtQ :

-

putative ABC iron siderophore transporter

- ybtT :

-

yersiniabactin synthesis enzyme

- ybtU :

-

thiazolinyl imide reductase

References

Brisse S, Passet V, Grimont PA. Description of Klebsiella quasipneumoniae sp. nov., isolated from human infections, with two subspecies, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae subsp. nov. and Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae subsp. nov., and demonstration that Klebsiella singaporensis is a junior heterotypic synonym of Klebsiella variicola. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64(9):3146–52.

Shon AS, Bajwa RP, Russo TA. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence. 2013;4(2):107–18.

Breurec S, Melot B, Hoen B, Passet V, Schepers K, Bastian S, Brisse S. Liver abscess caused by infection with community-acquired Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(3):529.

Wacharotayankun R, Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Tanaka K, Akashi T, Mori M, Kato N. Enhancement of extracapsular polysaccharide synthesis in Klebsiella pneumoniae by RmpA2, which shows homology to NtrC and FixJ. Infect Immun. 1993;61(8):3164–74.

Zhang Y, Zhao C, Wang Q, Wang X, Chen H, Li H, Zhang F, Li S, Wang R, Wang H. High prevalence of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in China: geographic distribution, clinical characteristics, and antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(10):6115–20.

Compain F, Babosan A, Brisse S, Genel N, Audo J, Ailloud F, Kassis-Chikhani N, Arlet G, Decré D. Multiplex PCR for detection of seven virulence factors and K1/K2 capsular serotypes of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(12):4377–80.

Versalovic J, Carroll KC, Funke G, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Warnock DW. Manual of clinical microbiology. 10th ed. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology; 2010.

CLSI. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically. Approved Standard- Tenth Edition. CLSI document. M07- A10. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Twenty fifth International Supplement. CLSI document M100-S25. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

Brisse S, Fevre C, Passet V, Issenhuth-Jeanjean S, Tournebize R, Diancourt L, Grimont P. Virulent clones of Klebsiella Pneumoniae: identification and evolutionary scenario based on genomic and phenotypic characterization. PLoS One. 2009;4:3–e4982.

Turton JF, Baklan H, Siu LK, Kaufmann ME, Pitt TL. Evaluation of a multiplex PCR for detection of serotypes K1, K2 and K5 in Klebsiella sp. and comparison of isolates within these serotypes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;284(2):247–52.

Veeraraghavan B, Anandan S, Sekar SK, Gopi R, Ragupathi NK, Ramesh S, Verghese VP, Korulla S, Mathai S, Sangal L, Joshi S. First report on the draft genome sequences of Corynebacterium diphtheriae isolates from India. Genome Announce. 2016;4(6):e01316.

Shankar C, Nabarro LE, Ragupathi NK, Sethuvel DP, Daniel JL, Veeraraghavan B. Draft genome sequences of three hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from bacteremia. Genome Announce. 2016;4(6):e01081–16.

Shankar C, Santhanam S, Kumar M, Gupta V, Ragupathi NK, Veeraraghavan B. Draft genome sequence of an extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-positive Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strain with novel sequence type 2318 isolated from a neonate. Genome Announce. 2016;4(6):e01273–16.

Shankar C, Nabarro LE, Sethuvel DP, Raj A, Ragupathi NK, Doss GP, Veeraraghavan B. Draft genome of a hypervirulent Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae with novel sequence type ST2320 isolated from a chronic liver disease patient. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;9:30–1.

Fu Y, Zhang F, Zhang W, Chen X, Zhao Y, Ma J, Bao L, Song W, Ohsugi T, Urano T, Liu S. Differential expression of bla SHV related to susceptibility to ampicillin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29(3):344–7.

Fang CT, Lai SY, Yi WC, Hsueh PR, Liu KL, Chang SC. Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:284–93.

Lin YT, Jeng YY, Chen TL, Fung CP. Bacteremic community-acquired pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: clinical and microbiological characteristics in Taiwan, 2001-2008. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):1.

Zhang Y, Zeng J, Liu W, Zhao F, Hu Z, Zhao C, Wang Q, Wang X, Chen H, Li H, Zhang F, Li S, Cao B, Wang H. Emergence of a hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from clinical infections in China. J Inf Secur. 2015;71(5):553–60.

Russo TA, Shon AS, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Pomakov AO, Visitacion MP. Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae secretes more and more active iron-acquisition molecules than “classical” K. pneumoniae thereby enhancing its virulence. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26734.

Jung SW, Chae HJ, Park YJ, Yu JK, Kim SY, Lee HK, Lee JH, Kahng JM, Lee SO, Lee MK, Lim JH. Microbiological and clinical characteristics of bacteraemia caused by the hypermucoviscosity phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(02):334–40.

Sah JP, Shah SK, Sharma B, Shah M, Salahuddin M, Mahato RV, Yadav C, Razin MS, Rashid M. Siderophore production: a unique quality of pathogenic Klebsiella pneumonia to survive in low iron concentration. Asian J Med Biol Res. 2015;1(1):130–8.

Pomakova DK, Hsiao CB, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Keynan Y, Russo TA. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(6):981–9.

Chen YT, Chang HY, Lai YC, Pan CC, Tsai SF, Peng HL. Sequencing and analysis of the large virulence plasmid pLVPK of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Gene. 2004;337:189–98.

Tang HL, Chiang MK, Liou WJ, Chen YT, Peng HL, Chiou CS, Liu KS, Lu MC, Tung KC, Lai YC. Correlation between Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying pLVPK-derived loci and abscess formation. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(6):689–98.

Hsieh PF, Lin TL, Lee CZ, Tsai SF, Wang JT. Serum-induced iron-acquisition systems and TonB contribute to virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae causing primary pyogenic liver abscess. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1717–27.

Russo TA, Olson R, MacDonald U, Beanan J, Davidson BA. Aerobactin, but not yersiniabactin, salmochelin, or enterobactin, enables the growth/survival of hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae ex vivo and in vivo. Infect Immun. 2015;83(8):3325–33.

Lawlor MS, O'Connor C, Miller VL. Yersiniabactin is a virulence factor for Klebsiella pneumoniae during pulmonary infection. Infect Immun. 2007;75(3):1463–72.

Huang YJ, Liao HW, Wu CC, Peng HL. MrkF is a component of type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Res Microbiol. 2009;160(1):71–9.

Lagos R, Baeza M, Corsini G, Hetz C, Strahsburger E, Castillo JA, Vergara C, Monasterio O. Structure, organization and characterization of the gene cluster involved in the production of microcin E492, a channel-forming bacteriocin. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42(1):229–43.

Yu WL, Ko WC, Cheng KC, Lee CC, Lai CC, Chuang YC. Comparison of prevalence of virulence factors for Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses between isolates with capsular K1/K2 and non-K1/K2 serotypes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;62(1):1–6.

Cubero M, Grau I, Tubau F, Pallarés R, Dominguez MA, Liñares J, Ardanuy C. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clones causing bacteraemia in adults in a teaching hospital in Barcelona, Spain (2007–2013). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(2):154–60.

Qu TT, Zhou JC, Jiang Y, Shi KR, Li B, Shen P, Wei ZQ, Yu YS. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in East China. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1.

Luo Y, Wang Y, Ye L, Yang J. Molecular epidemiology and virulence factors of pyogenic liver abscess causing Klebsiella pneumoniae in China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(11):O818–24.

Acknowledgements

We thank the team of curators of the Institut Pasteur MLST system (Paris, France) for importing novel profiles at http://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr. We thank Dr. Suresh Kumar R.S., Department of Clinical Microbiology, Christian Medical College,Vellore, for technical assistance in whole genome analysis.

Funding

This work has been funded by Fluid Research Grant, Christian Medical College, Vellore for whole genome sequencing.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS: Laboratory methods and manuscript writing. BV: Study design and manuscript writing and correction. LN: Collection of patient details, manuscript writing and correction. RR, NR: Laboratory methods and analysis of whole genome sequencing. PR: Study design, collection of patient details and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Christian Medical College, Vellore, India. This is a retrospective study in which the isolates are used without the patient identifier and hence patient consent was not obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shankar, C., Veeraraghavan, B., Nabarro, L.E.B. et al. Whole genome analysis of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from community and hospital acquired bloodstream infection. BMC Microbiol 18, 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1148-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1148-6