Abstract

Background

Hibernation is a physiological state exploited by many animals exposed to prolonged adverse environmental conditions associated with winter. Large changes in metabolism and cellular function occur, with many stress response pathways modulated to tolerate physiological challenges that might otherwise be lethal. Many studies have sought to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of mammalian hibernation, but detailed analyses are lacking in reptiles. Here we examine gene expression in the Australian central bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps) using mRNA-seq and label-free quantitative mass spectrometry in matched brain, heart and skeletal muscle samples from animals at late hibernation, 2 days post-arousal and 2 months post-arousal.

Results

We identified differentially expressed genes in all tissues between hibernation and post-arousal time points; with 4264 differentially expressed genes in brain, 5340 differentially expressed genes in heart, and 5587 differentially expressed genes in skeletal muscle. Furthermore, we identified 2482 differentially expressed genes across all tissues. Proteomic analysis identified 743 proteins (58 differentially expressed) in brain, 535 (57 differentially expressed) in heart, and 337 (36 differentially expressed) in skeletal muscle. Tissue-specific analyses revealed enrichment of protective mechanisms in all tissues, including neuroprotective pathways in brain, cardiac hypertrophic processes in heart, and atrophy protective pathways in skeletal muscle. In all tissues stress response pathways were induced during hibernation, as well as evidence for gene expression regulation at transcription, translation and post-translation.

Conclusions

These results reveal critical stress response pathways and protective mechanisms that allow for maintenance of both tissue-specific function, and survival during hibernation in the central bearded dragon. Furthermore, we provide evidence for multiple levels of gene expression regulation during hibernation, particularly enrichment of miRNA-mediated translational repression machinery; a process that would allow for rapid and energy efficient reactivation of translation from mature mRNA molecules at arousal. This study is the first molecular investigation of its kind in a hibernating reptile, and identifies strategies not yet observed in other hibernators to cope stress associated with this remarkable state of metabolic depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hibernation is an extreme state of inactivity used among diverse animal lineages to cope with low or unpredictable food availability and unfavourable seasonal conditions during winter. Hibernation involves long periods of hypometabolism (torpor), often interrupted by shorter periods of euthermia (interbout arousal). These periods of euthermia allow animals to rewarm and replenish gene and protein products; processes that are virtually halted during torpor [1]. Two decades of molecular studies of hibernation have focused on mammals, such as bears and squirrels [2,3,4,5,6,7,8], and recently marsupials [9], with little consideration of hibernation in reptiles. Debate surrounds the use of the word ‘hibernation’ in reptiles, with the thought that the lack of active body temperature regulation and inconsistent use of torpor necessitates an alternative term, i.e. ‘brumation’ [10]. However, there is large variation in physiology even between hibernating mammals, notably in tenrec [11], implying that hibernation is not one specific physiological state. As such, herein ‘hibernation’ will be used to describe the state of reptilian winter dormancy. Much like in mammals, reptilian hibernation also involves radical changes in behaviour and physiology [12].

In mammals, hibernation is achieved through a complex reprogramming of biological processes that leads to a drastic reduction in basal metabolic rate, transcription and translation, oxygen consumption, heart rate, and core body temperature, and an increase in physiological stress tolerance [13]. Hibernators employ general adaptive responses across all tissue types, and exhibit a range of tissue-specific responses. For example, during hibernation neuroprotective processes are activated in the brain (reviewed in [14]), contractive strength is increased in the heart [15, 16], and atrophy is limited in skeletal muscle [7, 16].

Hibernation in mammals is governed transcriptionally via chromatin modification and DNA methylation, post-transcriptionally via microRNAs (miRNAs), and post-translationally via protein modifications such as SUMOylation (reviewed in [13]). While non-cleavage translational repression of mRNAs via miRNAs is thought to be important in mammalian hibernation, as of yet, there is no direct evidence.

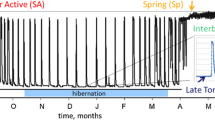

Exploring mechanisms used by different species to cope with extreme conditions and stressors may yield information pertinent to human disease, such as age-associated neurodegeneration, muscle atrophy, and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Studies on non-traditional model species, which have evolved different physiological strategies to cope with extreme and variable conditions, provide this critically important perspective. The Australian central bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps) is an excellent model to study reptilian hibernation because the genome is sequenced [17], and hibernation that mimics natural hibernation can be easily induced in captivity. Under natural conditions, bearded dragons hibernate by burying themselves in the soil or seeking refuge in fallen logs or tree stumps [12]. Typically, hibernation occurs between May and September, the coldest months of the year, where temperatures range from 5 °C to 18 °C. While physiological studies of bearded dragon hibernation in the wild is lacking, the nature of hibernation sites (buried) suggests the lizards have reduced breathing and heart rates during hibernation, with body temperatures reflecting that of ambient temperature (as they are ectothermic). However, unlike mammalian hibernators, the central bearded dragon is not known to have interbout arousals, with rewarming achieved through basking after arousal.

We profiled gene expression using mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) in three tissues (brain, heart and skeletal muscle) at three time points: 1) late hibernation; 2) 2 days post-arousal (pre-feed); and 3) 2 months post-arousal. We performed label-free proteomic quantification in the same three tissues at two time points: 1) late hibernation and 2) 2 months post-arousal. Differentially expressed genes and proteins were analyzed to determine overrepresented biological pathways during hibernating and waking periods. We discovered tissue-specific pathways that protect against the stress of reptilian hibernation and provide the evidence for multiple levels of gene expression regulation that may govern the physiological changes associated with hibernation.

Results

Differential gene and protein expression

Hierarchical clustering of the 3000 most highly expressed genes discovered with RNA-seq in brain, heart, and skeletal muscle grouped samples of the same tissue (Fig. 1a). Within the tissue-specific clusters, three biological replicates of hibernating individuals were separated from the two post-arousal time points, which clustered together as a single group. Since the two post-arousal time points clustered together and differential gene expression analysis revealed minor differences in expression between the two post-arousal time points (Additional file 1: Table S1), they were treated as a single time point for all subsequent differential gene expression analyses. The greatest number of differentially expressed genes between hibernating and aroused animals was observed in skeletal muscle, followed by heart, and then brain (Fig. 1b, Additional file 1: Table S1). A subset of 1311 genes was upregulated in all tissue types during hibernation and 1171 genes were downregulated (Fig. 1b).

Differential gene expression and gene ontology enrichment analysis. a Heatmap of the 3000 most highly expressed genes in all 27 samples with hierarchical clustering of samples. Each column represents a sample, and each row represents a gene. Each tile in the heatmap shows the normalized expression of a gene (Z-score), which was calculated by subtracting the mean expression value (counts per million) of a gene across all samples from the sample specific expression value, then divided by the standard deviation of the mean expression value of the gene. Hierarchical clustering and the dendogram were calculated using Ward’s method. Colour key shows Z-score, with blue indicating lower expression and red indicating higher expression compared to the mean across all samples. b Bar plot of the number of differentially expressed genes during hibernation as calculated in EdgeR (Log2 fold change > 0.585 – i.e. 1.5-fold change – and FDR < 0.05). The number of differentially expressed genes are overlaid on the bars. c Bar plot of selected enriched gene ontology (GO) terms of upregulated and downregulated genes common to all tissues during hibernation, with color indicating FDR (q-value) of the GO term. d Donut plot of significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05) biological process GO terms for upregulated genes common to all tissues in hibernating individuals. e Donut plot of significantly enriched biological process GO terms for downregulated genes common to all tissues in hibernating individuals. The size of each segment is relative to the number of genes that fall within the specific gene ontology in our dataset

Considering the small differences in gene expression between 2 days post-arousal and 2 months post-arousal samples (Additional file 1: Table S1), 2 days post-arousal individuals were excluded from the proteomic analysis. Across all individuals (hibernators and awake) in brain, 743 proteins were identified, with the brain-specific proteins MBP, NEFM, and ATP1A2 most abundant (Additional file 2: Table S2). Twenty-seven of these proteins were upregulated, and 31 downregulated. In heart, the most abundant proteins were the muscle-specific proteins ACT, CKM, and MYH15. Of the 535 proteins identified, 29 were upregulated, and 28 downregulated during hibernation. In skeletal muscle, 337 proteins were identified, with muscle-specific proteins (CKM, TPM2, and TNNI2) the most abundant. Twenty of these proteins were upregulated, and 16 downregulated during hibernation. Overall, the correlation between mRNA and protein expression was very limited. In brain, there were 54 differentially expressed genes in the proteome that were detected in the transcriptome. However, in the transcriptome only 14 (26%) correlated with the proteome (2 upregulated and 12 downregulated during hibernation). This low correlation was mirrored in heart. Of 50 differentially expressed genes in the proteome that were detected in the trancriptome, 15 (30%) were correlated (1 upregulated and 14 downregulated during hibernation). Finally, skeletal muscle displayed the lowest correlation between proteome and transcriptome. There were 33 differentially expressed genes in the proteome, with just two (6%) correlating with the transcriptome. This low correlation may be due to the relatively low number of identified genes in the proteome (primarily high abundance proteins) compared to the transcriptome. For example, in brain 10,000 genes were identified with a counts per million (CPM) > 10, while only 735 proteins were identified. This reflects a mere 7% of transcripts that have associated proteomic data.

Biological processes common to all tissues examined

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the 1311 common upregulated genes in hibernators identified 259 biological process GO terms that were significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05) (Fig. 1d and Additional file 3: Table S3). These processes belonged to two major categories: 1) regulatory mechanisms of gene expression, protein translation and protein function; 2) cellular stress response and mitigation of stress severity (Fig. 1c).

Regulation of gene expression

During hibernation, gene expression appears to be regulated at transcription, post-transcription, and post-translation across all tissues examined. Chromatin organization (GO:0006325) was enriched during hibernation (Fig. 1c and Additional file 3: Table S3); with 115 upregulated genes that included members of epigenetic modifying complexes such as the Sin3a histone deacetylase (HDAC) complex, the SWI/SNF complex, the Ada2a-containing (ATAC) complex, and Polycomb-group genes (Fig. 2a). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) supported this finding, with enrichment of similar biological pathways, including chromatin organization (M13550) and regulation of gene expression, epigenetic (M16267), observed in during hibernation in all tissues (Additional file 4: Table S4). While chromatin modifying proteins were not differentially expressed in the proteomic data, changes in histone protein expression were evident across all tissues. H1F0 and HIST1H1D were upregulated during hibernation in brain (Fig. 3c). In contrast, these two proteins were downregulated during hibernation in heart, whereas H4 was upregulated (Fig. 3g). In skeletal muscle, H4 and H2B1C were both downregulated during hibernation (Fig. 3i).

Differential expression of genes within enriched pathways during hibernation shared by all examined tissue. Mean (across biological replicates, ± 1 standard error) expression, measured in counts per million (CPM), of genes in brain (red), heart (green), and skeletal muscle (blue). Expression is shown for hibernators (triangles) and non-hibernators (circles). Panels a to d display genes related to gene expression regulatory mechanisms. Panels e to h display genes related to stress responses. The genes are from the following biological processes: a chromatin modification, b gene silencing by miRNA, c protein SUMOylation, d protein ubiquitination, e cell cycle arrest, f hypoxia response, g p38-MAPK signaling pathway, and h NF-κB signaling. All plotted on a log10 scale

Differentially expressed proteins discovered between hibernators and 2 months post-arousal individuals within tissues. Mean (across biological replicates, ± 1 standard error) normalized spectral counts of proteins. Expression is shown for hibernators (triangles) and non-hibernators (circles). Panels a to c display differentially expressed proteins in brain; panels d to h display differentially expressed proteins in heart; and panels i to k display differentially expressed proteins in skeletal muscle. See Additional file 3: Table S3 for fold-changes and full list of protein counts

Regulation of translation (GO:0006417) (51 genes) was enriched during hibernation, and there were 18 genes upregulated during hibernation that modulate gene expression by miRNAs (GO:0060964) (Additional file 3: Table S3). GSEA reinforced this enrichment (gene silencing by RNA; M16422) in all tissues (Additional file 4: Table S4). Importantly, these included genes required for miRNA-mediated translational repression (Fig. 2b). Notably, the cleavage-competent RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) subunit AGO2 (which results in mRNA degradation) was not differentially expressed (false discovery rate (FDR) > 0.05) between hibernators and non-hibernators. Finally, during hibernation there were enrichments for both protein SUMOylation (GO:0016925) (20 genes) and ubiquitination (GO:0016567) (104 genes) (Figs. 2c and d; Additional file 3: Table S3); an observation also supported by the GSEA in all tissues (Additional file 4: Table S4).

Response to stress

Genes associated with oxidative stress, hypoxia, DNA damage and heat shock pathways were upregulated during hibernation in all examined tissues (Fig. 1c), along with 55 genes associated with negative regulation of cell cycle processes (GO:0010948) (Additional file 3: Table S3). Eleven of these 55 genes are important in the regulation of p53-mediated cell cycle arrest (Fig. 2e), including TP53 and CDKN1A. Additionally, the p53-dependant G1 DNA damage response (M770) reactome pathway was highly enriched in all three tissues during hibernation (Additional file 4: Table S4). Genes that regulate transcription in response to hypoxia (GO:0061418) were also upregulated, and included the critical hypoxia response genes EP300, CREBBP, and HIF3A. A further three genes important for mediating hypoxia tolerance (MTDH, TRPM7, and CBX4) were also upregulated (Fig. 2f).

The p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade is responsive to various environmental stressors [18]. Ten genes within this signaling cascade (GO:1900744), including three MAP 3Ks (MAP kinase kinase kinase), were upregulated in all tissues during hibernation. A further two MAP 3Ks and three MAPKs were also upregulated in tissues of hibernators (Fig. 2g).

Although undetected in the GO enrichment analyses, GSEA revealed that NF-κB signaling (M13738) was enriched during hibernation in all tissues (Additional file 4: Table S4). Specifically, seven genes within the NF-κB signaling pathway; a central regulator of oxidative stress response [19], were upregulated during hibernation. These included NF-κB transcription factors, upstream inducers of NF-κB signaling, and downstream target genes known to alleviate oxidative stress (Fig. 2h).

Modulation of metabolism

Modulation of metabolic genes is a common feature in hibernators [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. GO analysis of the 1171 common downregulated genes revealed 44 enriched biological processes (Fig. 1e and Additional file 1: Table S1). This observation is directly supported by the GSEA, where the majority of enriched biological pathways post-arousal were related to metabolism (Additional file 4: Table S4). Enriched biological processes were predominantly related to metabolism, including: lipid catabolic processes (31 genes – GO:0016042), oxidation-reduction processes (91 genes – GO:0055114), and carbohydrate catabolic processes (16 genes – GO:0016052) (Additional file 3: Table S3). Furthermore, we observed a downregulation of three key ketone metabolic genes (BDH2, ACAT1, and OXCT1), which are necessary for metabolism when liver glycogen is depleted (Additional file 1: Table S1). Downregulated carbohydrate catabolism genes were predominantly related to glycoprotein and glycolipid metabolism (NEU1, NEU2, ENOSF1, and NAGA), glycosyl metabolism (AGL and MAN2C1), and galactose metabolism (GALE and GALT) (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Enriched GO terms of common upregulated genes during hibernation related to metabolism were predominantly regarded carbohydrate metabolism, including regulation of carbohydrate metabolic process (29 genes – GO:0006109) and regulation of gluconeogenesis (11 genes – GO:0006111). Specifically, this included PFKFB3, which stimulates glycolysis, GSK3A, which controls glycogen synthesis, and FBP1, the rate limiting enzyme of gluconeogenesis.

Corroborating our RNA-seq results, the proteomic analysis revealed differential expression of proteins involved in metabolic processes (particularly glucose metabolism) during hibernation in all tissues. In brain, two proteins upregulated during hibernation (ALDOA and ALDOC) are critical enzymes in glycolysis (Fig. 3b). In heart, six upregulated proteins (NDUFB10, COX6A1, NDUFS6, NDUFA13, NDUFS3, and UQRQ), and two downregulated proteins (UQCR10 and COX4I1) are important in the respiratory electron transport chain. Additionally, three upregulated proteins (DLAT, PDHA1, and IDH3A) are involved in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. In skeletal muscle three proteins (NDUFV2, NDUFS6, and SDHA), important in the respiratory electron transport chain, were also upregulated during hibernation, whereas one (NDUFA5) was downregulated.

Tissue-specific responses during hibernation

GSEA revealed an enrichment for the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) disease pathway Alzheimer’s disease (H00056) in the brain post-arousal (Additional file 4: Table S4). Three genes downregulated during hibernation (PS1, PS2, and APOE) are linked to early onset Alzheimer’s disease (Additional file 1: Table S1). Furthermore, five genes responsible for the phosphorylation of the microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT – an important protein in the central nervous system) were upregulated during hibernation (Fig. 4a). Additionally, in the bearded dragon, we observed that two N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) genes were differentially expressed during hibernation: GRIN1 was downregulated during hibernation, and GRIN2B was upregulated during hibernation (Fig. 4b). Proteomic analysis revealed four proteins involved in synaptic plasticity (SNAP25, MAPT, VGF, and SYNGAP1) were downregulated in brain during hibernation (Fig. 3a).

Differential expression of genes within tissue-specific processes. Mean expression (across biological replicates, ± 1 standard error), measured in counts per million (CPM). Expression is shown for hibernators (triangles) and non-hibernators (circles). The genes are from the following brain-specific processes: a microtubule-associated protein Tau kinases, b N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor genes; heart-specific processes: c actin cytoskeleton organization, d cardiac muscle transcription factors; and skeletal muscle-specific processes: e the TGF-β signaling pathway/BMP pathway, and f the PGC-1α pathway. See Additional file 1: Table S1 for fold-changes and false discovery rates

During mammalian hibernation, transcription factors responsible for cardiac muscle development, and induction of cardiac hypertrophy, are important in maintaining cardiac function [28]. In bearded dragon, four cardiac transcription factors and PPP3CC (a cardiac hypertrophy regulator) were upregulated in heart during hibernation (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, genes required for cardiac remodeling and associated with actin cytoskeleton modulation were upregulated during hibernation, including three myosin genes and two actin genes (Fig. 4d). Proteomic analysis revealed 5 differentially expressed proteins (ANXA6, CTNNA3, HSPB6, SLC8A1, and LMNA) involved in regulating muscle system processes (Fig. 3d), and 2 proteins (CSRP3 and NEBL) involved in actin binding (Fig. 3e).

In skeletal muscle, the transforming growth factor beta-receptor (TGF-β) signaling pathway and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway act antagonistically to balance muscle atrophy and hypertrophy [29]. We observed upregulation of three positive regulators of the BMP signaling pathway, and four positive regulators of the TGF-β pathway. Three muscle atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases were also upregulated during hibernation (Fig. 4e). The critical TGF-β gene myostatin (MSTN) was not differentially expressed between hibernating and awake animals. Finally, we observed upregulation of PPARGCIA (which encodes PGC-1α; the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis), along with two of its activators, and three downstream targets (Fig. 4f); a process which is known to be important for prevention of muscle atrophy in mammals [30]. Three differentially expressed proteins identified by proteomic analysis are involved in muscle function (DES, TNNI1, and ACTN3); particularly muscle filament sliding (Fig. 3k).

Discussion

Hibernation in reptiles is poorly studied compared to mammals. Beyond large-scale physiological responses, such as reduced heart and metabolic rate [31], the strategies common (and different) to hibernators from the two clades remain largely unknown. This study is the first to provide insight into the molecular pathways employed by a reptile during hibernation. We identified similarities between mammal and reptile hibernation, as well as responses that may be novel to the bearded dragon.

Recently, the use of steady state abundances of mRNA and proteins during hibernation has been scrutinized given that hibernation is a non-steady state condition. Some protiens do not function during hibernation as they do in steady state conditions, notably regulation of transcription by p53 [32]. However, for this study, we assume functional equivalence of biological processes during hibernation and after arousal. Additionally, transcriptomic and proteomic profiles were correlated to gain a multi-level understanding. Biological pathways (identified by gene ontology and gene set enrichment analyses) and downstream targets, rather than specific genes, were focused on to gain a more nuanced representation of physiological responses during hibernation.

Control of gene expression

Evidence for multiple levels of gene regulation in hibernating bearded dragons was observed, which is unsurprising considering that alteration of gene expression is known to be critical for hibernation in mammals [13]. Accordingly, we identified upregulation of genes involved in RISC-mediated gene silencing in all tissues of hibernating bearded dragons (Fig. 2b). Tissue-specific miRNA expression has been reported during hibernation in thirteen-lined ground squirrels [33,34,35], little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) [36,37,38], monito del monte (Dromiciops gliroides) [6], and wood frog (Rana sylvatica) [39] (Fig. 5).

Summary of molecular mechanisms utilized during hibernation by the central bearded dragon and other hibernators. For each biological process, a tick indicates there is sufficient evidence to suggest that the process occurs, whereas a cross indicates a lack of, or insufficient, evidence that the process occurs rather than not occurring. Major vertebrate clades are identified by different colors (pink – reptile, yellow – mammal, and green – amphibian) on the phylogeny. All images used are the author’s own work

The CCR4-NOT complex is a master regulator of gene expression and is required for RISC-mediated translational repression via the recruitment of the translation initiation factor 4E-T [40,41,42,43]. During hibernation, we identified upregulation of three key CCR4-NOT complex subunits, in addition to EIF4ENIF1, which encodes for 4E-T. Furthermore, in hibernating animals AGO2 (necessary for cleavage-competent RISC) was not upregulated, instead AGO3; the catalytic subunit of non-cleavage-competent RISCs [44], was upregulated (Fig. 2b). We propose that an enrichment of non-cleavage-competent RISC machinery during hibernation may represent an important gene regulatory pathway for bearded dragon hibernation.

Together with enhanced stability and polyadenylation of mRNAs [45], non-cleavage miRNA-mediated repression of mRNAs would allow for energy efficient regulation of gene expression. Upon arousal from hibernation reactivation of translation from mature mRNA molecules does not require immediate transcription and RNA processing. This would explain how bearded dragons are able to restore normal metabolic function promptly after arousal; such as if they are disturbed during hibernation, and after emergence from hibernation.

Restructuring of chromatin appears to be necessary for gene expression regulation during vertebrate hibernation. Increased expression of components of the Sin3A-HDAC complex is common to bearded dragons (Fig. 2a), hibernating squirrels and frogs [46,47,48,49] (Fig. 5). Increased expression of genes in the silencing complexes ATAC and SWI/SNF, along with Polycomb group proteins (Fig. 2a), suggests that transcriptional control during hibernation requires the complicated interaction of many epigenetic modifiers. While differentially expressed chromatin remodeling proteins were not detected in the proteomic data, differential histone expression between hibernators and non-hibernators was apparent in all tissues (Fig. 3c, g and i). The role of histone expression in phenotypic plasticity is largely unknown; however, histone expression is important in genomic stability [50, 51], suggesting a potentially important role in hibernation.

An increased expression of small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMO) and ubiquitination genes was also observed during hibernation (Figs. 2c and d), which are known to modulate protein function in mammalian hibernation (reviewed in [13]). Given the important role SUMOylation plays in cellular stress protection (reviewed in [52]), reversible post-translational regulation appears to be a universal mechanism involved in vertebrate hibernation and stress response.

Response to cellular stress

Cellular stress responses in the bearded dragon appear consistent with those of mammalian hibernators [53, 54](Fig. 5). Patterns of cell cycle arrest are a common observation during hibernation in thirteen-lined ground squirrels and in hypoxic red-eared slider turtles [53, 55] (Fig. 5). In bearded dragon, the p53 stress response pathway may be important in mediating this response. During hibernation in ground squirrels, Pan et al. demonstrated that while p53 localizes to the nucleus, recruits RNA polymerase II and binds DNA, the lack of target gene activation suggests that p53 does not function equivalently during hibernation [32]. However, in bearded dragons, critical target genes (including CDKN1A, BAX, and GADD45A) were transcriptionally upregulated during hibernation in all tissues (Fig. 2e), suggesting that p53 is indeed functional. In bearded dragons, the oxidative stress response may be guided by the NF-κB stress response pathway; much like in mammalian hibernators [56,57,58,59] (Fig. 5). Increased expression of key target genes that protect against oxidative damage (HMOX1, NQO1, and OLFM4) during hibernation suggests active protection from the sudden upsurge of reactive oxygen species that follows metabolic arousal from hibernation.

Our data implies that increased neuroprotection in brain during hibernation in bearded dragons may be governed by reduced N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) function, ultimately preventing excitotoxicity: neuronal death by over-activation of glutamate receptors [60]. Downregulation of the NMDAR NR1 subunit gene GRIN1 suggests lowered abundance of NMDARs at synapses, thus reducing capacity for excitotoxicity (Fig. 4b).

Increased expression of MAPT kinases in the brain could result in hyperphosphoryation of MAPT (Fig. 4a); a process that occurs in some hibernating mammals [61](Fig. 5) and is rapidly reversed upon arousal [62,63,64]. Phosphorylated MAPT has reduced affinity for microtubules, which is suggested to cause disruption of NMDAR anchoring and, therefore, neuroprotection (reviewed in [65]). This process is proposed to protect against excitotoxicity in hibernating ground squirrels [66, 67], anoxia-tolerant turtles [66, 67], and hypoxia and ischemia tolerance in the brains of rats and piglets [68,69,70]. Notably, MAPT-deficient mice are protected from excitotoxic brain damage [71]. In bearded dragons, MAPT mRNA expression did not vary significantly between hibernating and post-arousal time points, however, protein expression did (Fig. 3a). The decreased abundance of MAPT protein in hibernating bearded dragons suggests that excitotoxicity prevention (via reduced receptor abundance and stability) is a critical protective measure in the brains of hibernators.

During mammal hibernation, cardiac hypertrophy increases contractile strength [15, 72]. Unlike hypertrophic cardiomyopathy disease in humans, cardiac hypertrophy in hibernators is beneficial and quickly reversed upon arousal [72]. The cardiac-specific transcription factors with increased expression during bearded dragon hibernation (Fig. 4c) have function in promoting cardiac hypertrophy [73], cardiac-specific gene expression [74], cardiac remodeling [75], and proper heart development [76]. Our data reflect those from hibernating ground squirrels (Fig. 5) [72, 77,71,72,80].

Cardiac hypertrophy requires modulation of the actin cytoskeleton and sarcomeres (the functional unit of muscle cells) [81]. This is mirrored by upregulation of actin and myosin genes during bearded dragon hibernation (Fig. 4d). Maintenance of proper cardiac function was also revealed by the higher protein abundance of CSRP3 and NEBL during hibernation (Fig. 3e). CSRP3 and NEBL bind actin and are important in maintaining muscle structure [82, 83], with mutations causing cardiomyopathy in mammals [84, 85].

Unique to bearded dragons, the important actin cytoskeletal gene PAK1 was upregulated in heart during hibernation (Fig. 5d). PAK1 regulates excitability and contractibility of cardiomyocytes (reviewed in [86]); with over-expression improving cardiac function in mice (reviewed in [87]), and deletion worsening hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [88]. Modulating actin organization and structure appears crucial for protecting cardiac function during hibernation.

In hibernating individuials we observed upregulated pathways involved in prevention of skeletal muscle atrophy. The transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathways are antagonistic; they act to induce skeletal muscle atrophy and hypertrophy, respectively [29]. The increased expression of positive regulators of both pathways during hibernation is counterintuitive (Fig. 4e). However, both pathways modulate common targets (e.g. SMAD4 and the Akt/mTOR signaling cascade), and it has been suggested that normal maintenance of muscle mass results from precise regulation of both pathways [29]. In ground squirrels, members of both the TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways are also upregulated during hibernation (Fig. 5) [89].

PGC-1α (encoded by PPARGC1A) is critical in muscle remodeling and mitochondrial biogenesis [90, 91]. Genes that activate PGC-1α have increased expression during hibernation in bearded dragons, as do downstream targets (Fig. 4f). High levels of PGC-1α reduces muscle atrophy in non-hibernators (reviewed in [30]) by maintaining mitochondrial function, limiting inflammatory responses, and reducing ROS production and oxidative damage [92]. Induction of PGC-1α during hibernation may also mediate the switch from fast-twitch to slow-twitch muscle fibers [93, 94] (Fig. 5), which is important for protecting the muscle from fatigue post-arousal. Upregulation of genes within the PGC-1α pathway during hibernation suggests that this process is occurring in bearded dragon (Fig. 4f). Moreover, the increased abundance of proteins within the mitochondrial respiratory chain during hibernation (Fig. 3j) indicates preservation of mitochondrial function. We propose that increased expression of genes within the PGC-1α regulatory pathway contributes to resistance of skeletal muscle atrophy in hibernating animals.

Conclusion

Here we conducted the first transcriptional profiling and proteomic analysis of a reptile during hibernation and post-arousal from hibernation. There was evidence of neuroprotective strategies in the brain, maintenance of heart function via hypertrophy, and protection against skeletal muscle atrophy via increased antioxidant capacity and mitochondrial maintenance during hibernation. Many protective strategies we observed in hibernating bearded dragons were consistent with hibernating mammals, suggesting that there are limited solutions available to tolerate such extreme stress at the cellular level. However, bearded dragons had responses not previously detected in mammals, including the enrichment of non-cleavage competent RISC machinery during hibernation.

Methods

Animals and tissue collection

Central bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) were captive bred and housed at the University of Canberra under a protocol approved by the University of Canberra Animal Ethics Committee (CEAE17–08) and ACT Government License to Keep (K9640). Husbandry practices fulfill the Australian Code for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes 8th edition (2013) sections 3.2.13–3.2.23. Commercial sources of vegetables, mice and live insects (crickets and cockroaches) were provided as food, with water available ad libitum. Cages were cleaned thoroughly monthly, with superficial cleaning done daily (removal of faecal matter and unused food, maintenance of clean water containers). Logs and small branches were provided as basking perches and cardboard boxes provided as retreats. Enclosures were lit by a fluorescent lamp, a strong UVB light source, and a floodlamp (as a heat source) on a variable light:dark (L:D) cycle: August – mid-June (13hL:11hD; 22 °C), late June (2 weeks- 6hL: 18hD; 18 °C) and winter hibernation (0hL:24hD; 12 °C). For 2 weeks prior to hibernation, heat and light were reduced and animals were not fed. All heat and UV lights were turned off for 8 weeks and the facility temperature maintained at 12 °C, which stimulated any animals remaining active to hibernate. The conditions of artificial hibernation are chosen to mimic those that occur during natural hibernation, in that ambient temperatures are dropped, and light availability reduced. Body temperatures of hibernating animals was the same as ambient temperature (12 °C) due to the lack of access to heat sources. After arousal from hibernation, animals were subject to full summer conditions (13hL:11hD; 22 °C). Body temperatures of animals was at least 22 °C (ambient) with the addition of access to a heat source.

Whole brain, whole heart and femoral skeletal muscle tissue were collected from three individuals at three time points: late hibernation, 2 days post-arousal and 2 months post-arousal. All samples were used in the transcriptomic analysis, while only late hibernation and 2 months post-arousal samples were used in the proteomic analysis. All lizards were male. Tissues were collected immediately after euthanizing (lethal injection of sodium pentobarbitone 65 mg/kg by caudal venipuncture), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until RNA and protein extraction. All post-arousal animals were sacrificed between zeitgeber time (ZT) 3 and ZT5, where ZT0 is lights on and ZT13 is lights off. Hibernating animals were sacrificed between circadian time (CT) 3 and CT5, where CT0 is the same time of day as ZT0, however, without lights turning on.

RNA preparation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from 50 mg of each tissue. Tissue extracts were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Thermofisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) using T10 Basic ULTRA-TURRAX® Homogenizer (IKA, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany), and RNA purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An on-column DNase digestion was performed with RNase-free DNase (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). For each sample, 5–10 μg of high integrity RNA (RIN > 8) was poly-A selected. Libraries were constructed with the Illumina TruSeq Total RNA Stranded RNA kit, and 76 bp single-ended reads were generated on the Illumina NextSeq 500 platform at the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics (UNSW, Australia). All sequence data have been submitted to the NCBI short read archive under the BioProject ID PRJNA476034.

Raw read quality was analyzed with FastQC (v0.11.5) [95]. Trimmomatic (v0.36) [96] was used to trim the reads to remove low quality bases with the following options: HEADCROP:12 CROP:62 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15. Reads were mapped to the annotated reference genome of the central bearded dragon [17] with HiSat2 (v2.0.5) [97] using default options. HTseq-count (v0.9.1) [98] was used to count reads that overlapped genomic features with the following options: -s reverse -m union. Samples were normalized using the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method and differentially expressed genes was calculated with EdgeR (v3.20.8) [99] in a pairwise manner using the exact test method. Resultant P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to calculate FDR. Genes with a fold-change greater than 1.5 (log2 fold-change of 0.585) and FDR less than 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Gene ontology enrichment analysis related to differentially expressed genes were conducted with GOrilla using the human database (GO term database last updated December 9th 2017) [100]. Unranked lists of upregulated and downregulated genes in each condition and tissues were compared to a background list. The background list only included genes that were expressed (greater than 10 counts per million) within each tissue. For differentially expressed genes common to all tissues, only genes expressed in all three tissues were included in the background list. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [101] was performed for each tissue using defaults settings. Gene sets (Collection 2: Kegg, Biocarta and Reactome; Collection 5: GO Gene sets for Biological Process, Molecular Function and Cellular Component) were downloaded from MSigDB [102]. As with the differential gene expression analysis, the two post-arousal time points were collated as a single time point. All graphs were plotted with R (3.4.2) [103], RStudio (1.1.383) [104], and ggplot2 (2.2.1) [105].

Protein extraction and mass spectrometry

Total protein was extracted from 50 mg of tissue. Tissue extracts were homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA), cOmplete® and EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using T10 Basic ULTRA-TURRAX® Homogenizer (IKA, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany). Protein concentrations were determined using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermofisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Protein extracts were analyzed at the Bioanalytical Mass Spectrometry Facility at the Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre (UNSW, Australia) using label-free quantification mass spectrometry using standard protocol. Briefly, samples were digested with Trypsin (MS Grade, Thermofisher) and separated by nanoLC using an Ultimate nanoRSLC UPLC and autosampler system (Dionex, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Samples (2.5 μl) were concentrated and desalted with a micro C18 precolumn with H2O:CH3CN (98:2, 0.1% TFA) at 15 μl/min and a fritless nano column (75 μm × 15 cm) containing C18-AQ media (Dr Maisch, Ammerbuch-Entringen Germany). Peptides were eluted using a linear gradient of H2O:CH3CN (98:2, 0.1% formic acid) to H2O:CH3CN (64:36, 0.1% formic acid) at 200 nl/min over 60 min. 2000 V was applied to low volume titanium union and the tip positioned ~ 0.5 cm from the heated capillary (T = 275 °C) of an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos (Thermo Electron, Bremen, Germany) mass spectrometer. Positive ions were generated by electrospray and the Fusion Lumos operated in data dependent acquisition mode (DDA).

A survey scan m/z 350–1750 was acquired in the orbitrap (resolution = 120,000 at m/z 200, with an accumulation target value of 400,000 ions) and lockmass enabled (m/z 445.12003). Data-dependent tandem MS analysis was performed using a top-speed approach (cycle time of 2 s). MS2 spectra were fragmented by HCD (NCE = 30) activation mode and the ion-trap was selected as the mass analyzer. The intensity threshold for fragmentation was set to 25,000. A dynamic exclusion of 20 s was applied with a mass tolerance of 10 ppm.

Peak lists were generated using Mascot Daemon/Mascot Distiller (Matrix Science, London, England) and imported into the database search program Mascot (version 2.6.0, Matrix Science). Search parameters were: Precursor tolerance 4 ppm and product ion tolerances ±0.5 Da; Met (O) carboxyamidomethyl-Cys specified as variable modification, enzyme specificity was trypsin, with 1 missed cleavage possible. Peaks were searched against the reference genome of the central bearded dragon [17] and a non-redundant protein database from NCBI (Jan 2015).

Raw peak data were imported into Scaffold (Matrix Science, London, England) and analysed accordingly with default settings. Normalized peak lists were imported into R (3.4.2) [103] for analysis. Proteins were excluded if there was an average of less than three spectral counts across the biological replicates in both conditions. Proteins were considered differentially expressed if the standard error of the mean spectral counts of each condition (i.e. hibernation vs. post-arousal) did not overlap.

Abbreviations

- ATAC:

-

Ada2a-containing

- BMP:

-

Bone morphogenetic protein

- CPM:

-

Counts per million

- CT:

-

Circadian time

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- HDAC:

-

Histone deacetylase

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MAPT:

-

Microtubule associated protein tau

- miRNA:

-

microRNA

- mRNA-seq:

-

mRNA sequencing

- MSTN:

-

Myostatin

- NMDAR:

-

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- RISC:

-

RNA-induced silencing complex

- SUMO:

-

Small ubiquitin-like modifiers

- TCA:

-

Tricarboxylic acid

- TGF-β:

-

Transforming growth factor beta-receptor

- ZT:

-

Zeitgeber time

References

Van Breukelen F, Martin SL. Invited review: molecular adaptations in mammalian hibernators: unique adaptations or generalized responses. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(6):2640–7.

Van Breukelen F, Martin S. Reversible depression of transcription during hibernation. J Comp Physiol B. 2002;172(5):355–61.

Fuster G, Busquets S, Almendro V, López-Soriano FJ, Argilés JM. Antiproteolytic effects of plasma from hibernating bears: a new approach for muscle wasting therapy? Clin Nutr. 2007;26(5):658–61.

Hampton M, Melvin RG, Kendall AH, Kirkpatrick BR, Peterson N, Andrews MT. Deep sequencing the transcriptome reveals seasonal adaptive mechanisms in a hibernating mammal. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e27021.

Fedorov VB, Goropashnaya AV, Stewart NC, Tøien Ø, Chang C, Wang H, Yan J, Showe LC, Showe MK, Barnes BM. Comparative functional genomics of adaptation to muscular disuse in hibernating mammals. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(22):5524–37.

Hadj-Moussa H, Moggridge JA, Luu BE, Quintero-Galvis JF, Gaitán-Espitia JD, Nespolo RF, Storey KB. The hibernating south American marsupial, Dromiciops gliroides, displays torpor-sensitive microRNA expression patterns. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24627.

Zhang Y, Aguilar OA, Storey KB. Transcriptional activation of muscle atrophy promotes cardiac muscle remodeling during mammalian hibernation. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2317.

Zhang Y, Tessier SN, Storey KB. Inhibition of skeletal muscle atrophy during torpor in ground squirrels occurs through downregulation of MyoG and inactivation of Foxo4. Cryobiology. 2016;73(2):112–9.

Nespolo RF, Gaitan-Espitia JD, Quintero-Galvis JF, Fernandez FV, Silva AX, Molina C, Storey KB, Bozinovic F. A functional transcriptomics analysis in the relict marsupial Dromiciops gliroides reveals adaptive regulation of protective functions during hibernation. Mol Ecol. 2018.

Ultsch GR. Ecology and physiology of hibernation and overwintering among freshwater fishes, turtles, and snakes. Biol Rev. 1989;64(4):435–515.

Treat MD, Scholer L, Barrett B, Khachatryan A, McKenna AJ, Reyes T, Rezazadeh A, Ronkon CF, Samora D, Santamaria JF. Extreme physiological plasticity in a hibernating basoendothermic mammal, Tenrec ecaudatus. J Exp Biol. 2018;221(20):jeb185900.

Wells RW. Hibernation - bearded dragons. Herpetofauna. 1971;3:4–6.

Storey KB. Regulation of hypometabolism: insights into epigenetic controls. J Exp Biol. 2015;218(1):150–9.

Dave KR, Christian SL, Perez-Pinzon MA, Drew KL. Neuroprotection: lessons from hibernators. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;162(1):1–9.

Wickler SJ, Hoyt DF, van Breukelen F. Disuse atrophy in the hibernating golden-mantled ground squirrel, Spermophilus lateralis. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 1991;261(5):R1214–7.

Hindle AG, Otis JP, Epperson LE, Hornberger TA, Goodman CA, Carey HV, Martin SL. Prioritization of skeletal muscle growth for emergence from hibernation. J Exp Biol. 2015;218(2):276–84.

Georges A, Li Q, Lian J, O’Meally D, Deakin J, Wang Z, Zhang P, Fujita M, Patel HR, Holleley CE. High-coverage sequencing and annotated assembly of the genome of the Australian dragon lizard Pogona vitticeps. GigaScience. 2015;4(1):1–11.

Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. Mechanisms and functions of p38 MAPK signalling. Biochem J. 2010;429(3):403–17.

Morgan MJ, Liu Z-G. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Res. 2011;21(1):103–15.

Yan J, Barnes BM, Kohl F, Marr TG. Modulation of gene expression in hibernating arctic ground squirrels. Physiol Genomics. 2008;32(2):170–81.

Faherty SL, Villanueva-Cañas JL, Klopfer PH, Albà MM, Yoder AD. Gene expression profiling in the hibernating primate, Cheirogaleus medius. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8(8):2413–26.

Fedorov VB, Goropashnaya AV, Tøien Ø, Stewart NC, Chang C, Wang H, Yan J, Showe LC, Showe MK, Barnes BM. Modulation of gene expression in heart and liver of hibernating black bears (Ursus americanus). BMC Genomics. 2011;12(1):171.

Eddy SF, Morin P Jr, Storey KB. Differential expression of selected mitochondrial genes in hibernating little brown bats, Myotis lucifugus. J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol. 2006;305(8):620–30.

Han Y, Zheng G, Yang T, Zhang S, Dong D, Pan Y-H. Adaptation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha to hibernation in bats. BMC Evol Biol. 2015;15(1):88.

Wijenayake S, Luu BE, Zhang J, Tessier SN, Quintero-Galvis JF, Gaitán-Espitia JD, Nespolo RF, Storey KB. Strategies of biochemical adaptation for hibernation in a south American marsupial, Dromiciops gliroides: 4. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and metabolic fuel selection. Comp Biochem Physiol B: Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;224:32–7.

Boutilier RG, St-Pierre J. Adaptive plasticity of skeletal muscle energetics in hibernating frogs: mitochondrial proton leak during metabolic depression. J Exp Biol. 2002;205(15):2287–96.

Tamaoki K, Ishihara A, Yamauchi K. Expression pattern and histone acetylation of energy metabolic genes in Xenopus laevis liver in response to diet statuses. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol. 2019;331(2):120–7.

Akazawa H, Komuro I. Roles of cardiac transcription factors in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2003;92(10):1079–88.

Sartori R, Gregorevic P, Sandri M. TGFβ and BMP signaling in skeletal muscle: potential significance for muscle-related disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25(9):464–71.

Sandri M. Protein breakdown in muscle wasting: role of autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(10):2121–9.

Aleksiuk M. Reptilian hibernation: evidence of adaptive strategies in Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis. Copeia. 1976:170–8.

Pan P, Treat MD, van Breukelen F. A systems-level approach to understanding transcriptional regulation by p53 during mammalian hibernation. J Exp Biol. 2014;217(14):2489–98.

Wu C-W, Biggar KK, Luu BE, Szereszewski KE, Storey KB. Analysis of microRNA expression during the torpor-arousal cycle of a mammalian hibernator, the 13-lined ground squirrel. Physiol Genomics. 2016; physiolgenomics. 00005.02016.

Liu Y, Hu W, Wang H, Lu M, Shao C, Menzel C, Yan Z, Li Y, Zhao S, Khaitovich P. Genomic analysis of miRNAs in an extreme mammalian hibernator, the Arctic ground squirrel. Physiol Genomics. 2010.

Wu C-W, Biggar KK, Storey KB. Expression profiling and structural characterization of microRNAs in adipose tissues of hibernating ground squirrels. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2014;12(6):284–91.

Kornfeld SF, Biggar KK, Storey KB. Differential expression of mature microRNAs involved in muscle maintenance of hibernating little brown bats, Myotis lucifugus: a model of muscle atrophy resistance. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2012;10(5):295–301.

Yuan L, Geiser F, Lin B, Sun H, Chen J, Zhang S. Down but not out: the role of microRNAs in hibernating bats. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135064.

Biggar KK, Storey KB. Identification and expression of microRNA in the brain of hibernating bats, Myotis lucifugus. Gene. 2014;544(1):67–74.

Bansal S, Luu BE, Storey KB. MicroRNA regulation in heart and skeletal muscle over the freeze–thaw cycle in the freeze tolerant wood frog. J Comp Physiol B. 2016;186(2):229–41.

Piao X, Zhang X, Wu L, Belasco JG. CCR4-NOT deadenylates mRNA associated with RNA-induced silencing complexes in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(6):1486–94.

Fabian MR, Cieplak MK, Frank F, Morita M, Green J, Srikumar T, Nagar B, Yamamoto T, Raught B, Duchaine TF. miRNA-mediated deadenylation is orchestrated by GW182 through two conserved motifs that interact with CCR4–NOT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(11):1211–7.

Chekulaeva M, Mathys H, Zipprich JT, Attig J, Colic M, Parker R, Filipowicz W. miRNA repression involves GW182-mediated recruitment of CCR4–NOT through conserved W-containing motifs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(11):1218–26.

Collart MA. The Ccr4-not complex is a key regulator of eukaryotic gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2016;7(4):438–54.

Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song J-J, Hammond SM, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305(5689):1437–41.

Grabek KR, Behn CD, Barsh GS, Hesselberth JR, Martin SL. Enhanced stability and polyadenylation of select mRNAs support rapid thermogenesis in the brown fat of a hibernator. Elife. 2015;4:e04517.

Storey KB. Evidence for a reduced transcriptional state during hibernation in ground squirrels. Cryobiology. 2006;53(3):310–8.

Hudson NJ, Lonhienne T, Franklin CE, Harper GS, Lehnert S. Epigenetic silencers are enriched in dormant desert frog muscle. J Comp Physiol B. 2008;178(6):729–34.

Biggar Y, Storey KB. Global DNA modifications suppress transcription in brown adipose tissue during hibernation. Cryobiology. 2014;69(2):333–8.

Alvarado S, Mak T, Liu S, Storey KB, Szyf M. Dynamic changes in global and gene specific DNA methylation during hibernation in adult thirteen-lined ground squirrels, Ictidomys tridecemlineatus. J Exp Biol. 2015;218(Pt 11):1787–95.

Liang D, Burkhart SL, Singh RK, Kabbaj M-HM, Gunjan A. Histone dosage regulates DNA damage sensitivity in a checkpoint-independent manner by the homologous recombination pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(19):9604–20.

Wang R, Zheng X, Zhang L, Zhou B, Hu H, Li Z, Zhang L, Lin Y, Wang X. Histone H4 expression is cooperatively maintained by IKKβ and Akt1 which attenuates cisplatin-induced apoptosis through the DNA-PK/RIP1/IAPs signaling cascade. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41715.

Guo C, Henley JM. Wrestling with stress: roles of protein SUMOylation and deSUMOylation in cell stress response. IUBMB Life. 2014;66(2):71–7.

Wu C-W, Storey KB. Pattern of cellular quiescence over the hibernation cycle in liver of thirteen-lined ground squirrels. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(9):1714–26.

Luu BE, Wijenayake S, Zhang J, Tessier SN, Quintero-Galvis JF, Gaitán-Espitia JD, Nespolo RF, Storey KB. Strategies of biochemical adaptation for hibernation in a south American marsupial, Dromiciops gliroides: 3. Activation of pro-survival response pathways. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;224:26–31.

Biggar KK, Storey KB. Perspectives in cell cycle regulation: lessons from an anoxic vertebrate. Curr Genomics. 2009;10(8):573–84.

Allan ME, Storey KB. Expression of NF-κB and downstream antioxidant genes in skeletal muscle of hibernating ground squirrels, Spermophilus tridecemlineatus. Cell Biochem Funct. 2012;30(2):166–74.

Carey HV, Frank CL, Seifert JP. Hibernation induces oxidative stress and activation of NF-κB in ground squirrel intestine. J Comp Physiol B. 2000;170(7):551–9.

Wijenayake S, Luu BE, Zhang J, Tessier SN, Quintero-Galvis JF, Gaitán-Espitia JD, Nespolo RF, Storey KB. Strategies of biochemical adaptation for hibernation in a south American marsupial Dromiciops gliroides: 1. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and the cell stress response. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;224:12–8.

Luu BE, Wijenayake S, Zhang J, Tessier SN, Quintero-Galvis JF, Gaitán-Espitia JD, Nespolo RF, Storey KB. Strategies of biochemical adaptation for hibernation in a south American marsupial, Dromiciops gliroides: 2. Control of the Akt pathway and protein translation machinery. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;224:19–25.

Arundine M, Tymianski M. Molecular mechanisms of calcium-dependent neurodegeneration in excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2003;34(4):325–37.

Stieler JT, Bullmann T, Kohl F, Tøien Ø, Brückner MK, Härtig W, Barnes BM, Arendt T. The physiological link between metabolic rate depression and tau phosphorylation in mammalian hibernation. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e14530.

Arendt T, Stieler J, Strijkstra AM, Hut RA, Rüdiger J, Van der Zee EA, Harkany T, Holzer M, Härtig W. Reversible paired helical filament-like phosphorylation of tau is an adaptive process associated with neuronal plasticity in hibernating animals. J Neurosci. 2003;23(18):6972–81.

Su B, Wang X, Drew KL, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Physiological regulation of tau phosphorylation during hibernation. J Neurochem. 2008;105(6):2098–108.

Arendt T, Stieler J, Holzer M. Brain hypometabolism triggers PHF-like phosphorylation of tau, a major hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Neural Transm. 2015;122(4):531–9.

Arendt T, Bullmann T. Neuronal plasticity in hibernation and the proposed role of the microtubule-associated protein tau as a “master switch” regulating synaptic gain in neuronal networks. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2013;305(5):R478–89.

Zhao HW, Ross AP, Christian SL, Buchholz JN, Drew KL. Decreased NR1 phosphorylation and decreased NMDAR function in hibernating Arctic ground squirrels. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84(2):291–8.

Bickler PE, Donohoe PH, Buck LT. Hypoxia-induced silencing of NMDA receptors in turtle neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20(10):3522–8.

Mishra OP, Fritz KI, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M. NMDA receptor and neonatal hypoxic brain injury. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7(4):249–53.

Morikawa E, Mori H, Kiyama Y, Mishina M, Asano T, Kirino T. Attenuation of focal ischemic brain injury in mice deficient in the ε1 (NR2A) subunit of NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18(23):9727–32.

Fritz KI, Zubrow AB, Mishra OP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M. NMDA receptor modification during graded hypoxia in the cerebral cortex of newborn piglets. Neonatology. 2002;82(1):46–52.

Bi M, Gladbach A, Eersel J, Ittner A, Przybyla M, Hummel A, Chua SW, van der Hoven J, Lee WS, Müller J. Tau exacerbates excitotoxic brain damage in an animal model of stroke. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):473.

Tessier SN, Storey KB. Myocyte enhancer factor-2 and cardiac muscle gene expression during hibernation in thirteen-lined ground squirrels. Gene. 2012;501(1):8–16.

Wang K, Long B, Zhou J, Li P-F. miR-9 and NFATc3 regulate myocardin in cardiac hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(16):11903–12.

He A, Kong SW, Ma Q, Pu WT. Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(14):5632–7.

Kim Y, Phan D, Van Rooij E, Wang D-Z, McAnally J, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. The MEF2D transcription factor mediates stress-dependent cardiac remodeling in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(1):124–32.

Li QY, Newbury-Ecob RA, Terrett JA, Wilson DI, Curtis AR, Yi CH, Gebuhr T, Bullen PJ, Robson SC, Strachan T. Holt-Oram syndrome is caused by mutations in TBX5, a member of the Brachyury (T) gene family. Nat Genet. 1997;15(1):21–9.

Tessier SN, Storey KB. Expression of myocyte enhancer factor-2 and downstream genes in ground squirrel skeletal muscle during hibernation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;344(1–2):151–62.

Vermillion KL, Anderson KJ, Hampton M, Andrews MT. Gene expression changes controlling distinct adaptations in the heart and skeletal muscle of a hibernating mammal. Physiol Genomics. 2015;47(3):58–74.

Zhang Y, Storey KB. Expression of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and downstream muscle-specific proteins in ground squirrel skeletal and heart muscle during hibernation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;412(1–2):27–40.

Zhang Y, Storey KB. Regulation of gene expression by NFAT transcription factors in hibernating ground squirrels is dependent on the cellular environment. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2016;21(5):883–94.

Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(8):589–600.

Hoffmann C, Moreau F, Moes M, Luthold C, Dieterle M, Goretti E, Neumann K, Steinmetz A, Thomas C. Human muscle LIM protein dimerizes along the actin cytoskeleton and cross-links actin filaments. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(16):3053–65.

Hernandez DA, Bennett CM, Dunina-Barkovskaya L, Wedig T, Capetanaki Y, Herrmann H, Conover GM. Nebulette is a powerful cytolinker organizing desmin and actin in mouse hearts. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27(24):3869–82.

Geier C, Gehmlich K, Ehler E, Hassfeld S, Perrot A, Hayess K, Cardim N, Wenzel K, Erdmann B, Krackhardt F. Beyond the sarcomere: CSRP3 mutations cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(18):2753–65.

Perrot A, Tomasov P, Villard E, Faludi R, Melacini P, Lossie J, Lohmann N, Richard P, De Bortoli M, Angelini A. Mutations in NEBL encoding the cardiac Z-disk protein nebulette are associated with various cardiomyopathies. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12(2):263.

Ke Y, Lei M, Solaro RJ. Regulation of cardiac excitation and contraction by p21 activated kinase-1. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98(2):238–50.

Wang Y, Tsui H, Bolton EL, Wang X, Huang CL-H, Solaro RJ, Ke Y, Lei M. Novel insights into mechanisms for Pak1-mediated regulation of cardiac Ca2+ homeostasis. Front Physiol. 2015;6:76.

Liu W, Zi M, Naumann R, Ulm S, Jin J, Taglieri DM, Prehar S, Gui J, Tsui H, Xiao R-P. Pak1 as a novel therapeutic target for antihypertrophic treatment in the heart. Circulation. 2011;124(24):2702–15.

Brooks NE, Myburgh KH, Storey KB. Myostatin levels in skeletal muscle of hibernating ground squirrels. J Exp Biol. 2011;214(15):2522–7.

Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang C-Y, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1α drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature. 2002;418(6899):797.

Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98(1):115–24.

Kang C, Ji LL. PGC-1α overexpression via local transfection attenuates mitophagy pathway in muscle disuse atrophy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;93:32–40.

Xu R, Andres-Mateos E, Mejias R, MacDonald EM, Leinwand LA, Merriman DK, Fink RH, Cohn RD. Hibernating squirrel muscle activates the endurance exercise pathway despite prolonged immobilization. Exp Neurol. 2013;247:392–401.

Eddy SF, Storey KB. Differential expression of Akt, PPARγ, and PGC-1 during hibernation in bats. Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;81(4):269–74.

Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Reference Source. 2010.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20.

Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–60.

Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;31(2):166–9.

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40.

Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):48.

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(43):15545–50.

Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database Hallmark Gene Set Collection. Cell Systems. 2015;1(6):417-425

Team RCD. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation of statistical Computing; 2010.

Team R. RStudio: integrated development environment for R. in. Boston: RStudio, Inc.; 2016.

Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Ruscoe of the animal facility at the University of Canberra for animal husbandry and collecting tissue samples, and Ling Zhong at the Bioanalytical Mass Spectrometry Facility (BMSF) at the Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre (MWAC) for assistance with the mass spectrometry.

Funding

The project was funded by internally allocated funds from UNSW Sydney and in part by a grant from the Australian Research Council (DP170101147) awarded to AG and PW. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

RNA-seq data are available in the NCBI short read archive under the BioProject ID PRJNA476034 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/476034). Mass spectrometry data are available at the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD011171 and https://doi.org/10.6019/PXD011171 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD011171). Computer code for processing and analyzing sequence and mass spectrometry data is available on request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PDW, SW, DO and AG conceived and designed the study. AC and HP contributed to the design of the study. AC performed the experiments. AC performed the computational analysis of sequencing and mass spectrometry data. HP conducted Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of sequencing data. AG provided tissue samples. AC and PDW wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experimentation using animals was approved by the University of Canberra Animal Ethics Committee (CEAE17–08) and are in accordance with ACT Government License to Keep (K9640). Husbandry practices fulfill the Australian Code for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes 8th edition (2013) sections 3.2.13–3.2.23.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Differential gene expression of RNA sequencing. Full list of differentially expressed genes with FDR < 0.05 for brain, heart, skeletal muscle, and common genes as outputted from EdgeR. Log2 fold change is relative to hibernation (i.e. > 1 Log2FC is higher expression during hibernation). (XLSX 1302 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Gene ontology enrichment analysis data of differentially expressed genes. Full list of enriched biological pathway gene ontologies in upregulated and downregulated gene datasets in brain, heart, skeletal muscle, and common genes as outputted fromx GOrilla. (XLSX 140 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S3. Protein expression data. Full list of all proteins identified with label-free mass spectrometry by Scaffold. (XLSX 82 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) results of RNA sequencing data. GSEA results of RNA sequencing data, containing Biocarta, KEGG, Reactome, and Biological Pathway results. (XLSX 835 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Capraro, A., O’Meally, D., Waters, S.A. et al. Waking the sleeping dragon: gene expression profiling reveals adaptive strategies of the hibernating reptile Pogona vitticeps. BMC Genomics 20, 460 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5750-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5750-x