Abstract

Background

WD40 domains are abundant in eukaryotes, and they are essential subunits of large multiprotein complexes, which serve as scaffolds. WD40 proteins participate in various cellular processes, such as histone modification, transcription regulation, and signal transduction. WD40 proteins are regarded as crucial regulators of plant development processes. However, the systematic identification and analysis of WD40 proteins have yet to be reported in wheat.

Results

In this study, a total of 743 WD40 proteins were identified in wheat, and they were grouped into 5 clusters and 11 subfamilies. Their gene structures, chromosomal locations, and evolutionary relationships were analyzed. Among them, 39 and 46 pairs of TaWD40s were distinguished as tandem duplication and segmental duplication genes. The 123 OsWD40s were identified to exhibit synteny with TaWD40s. TaWD40s showed the specific characteristics at the reproductive developmental stage, and numerous TaWD40s were involved in responses to stresses, including cold, heat, drought, and powdery mildew infection pathogen, based on the result of RNA-seq data analysis. The expression profiles of some TaWD40s in wheat seed development were confirmed through qRT-PCR technique.

Conclusion

In this study, 743 TaWD40s were identified from the wheat genome. As the main driving force of evolution, duplication events were observed, and homologous recombination was another driving force of evolution. The expression profiles of TaWD40s revealed their importance for the growth and development of wheat and their response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Our study also provided important information for further functional characterization of some WD40 proteins in wheat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

WD40 proteins are also called WD40 domain-containing proteins, and they constitute a large gene family among eukaryote species [1]. WD40 is named from the WD dipeptide of its conserved domain and defined that every single repeat contains 44–60 amino acids, and there are a GH dipeptide and a WD dipeptide at N- and C-terminals, respectively [2]. Bovine β-transducin is the first identified WD40 protein [3], and its crystal structure possesses a seven-bladed β-propeller fold formed by repeats [4,5,6]. A strong hydrogen bond network produced by this WD domain structure improves the stability of WD40 proteins [7]. WD40 proteins exist extensively in all eukaryotes, but they are rarely found in prokaryotic proteomes, though a WD40 protein named PkwA was identified in a prokaryote in 1996 [8]. Only a small proportion of archaea proteomes (27 of 134) and bacterial proteomes (466 of 1679) have WD40 proteins [9].

The WD40 domain is slightly conservative in terms of protein sequence, thus, precisely predicting the number of WD40 repeats in a WD40 protein is difficult. The prevailing prediction methods for the analysis and identification of a WD40 domain are too conservative, for instance, the structural information of DNA damage binding protein 1 (DDB1) [10] and Sro7 [11] comprises seven or multiples of seven blades, but only some repeats can be identified through sequence-based classification methods in the prediction of their structures.

WD40 proteins are usually regarded as the scaffold of protein–protein interactions [12]. The number of WD40 repeats that form a β-propeller fold ranges from 5 to 8, more likely 7 [13, 14]. WD40 proteins have complex structures and functions; they can interact with diverse proteins in various ways and participate in extensive biological regulatory processes, such as DNA replication, damage response, histone recognition, transcriptional regulation, post-translational modification, signal transduction, protein degradation, and apoptosis [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

The WD40 protein family has been systematically identified in plant species, humans, silkworms, and prokaryotes [9, 25, 26]. It is reported that there were 237 WD40s in thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), 191 WD40s in cucumber (Cucumis sativus), 225 WD40s in foxtail millet (Setaria italica), and 579 WD40s in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), respectively. [27,28,29,30]. In the monocotyledonous model plant rice (Oryza sativa), 200 WD40 family members are clustered into 5 groups and classified into 11 subfamilies based on their domain compositions [31]. Although the WD40 family has been studied in many plant species, it has yet to be investigated in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), which is an important cereal crop worldwide. Wheat is rich in proteins, carbohydrates, and minerals. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), wheat production is predicted to account for 28.46% of the global cereal production (2.59 billion tons) by 2017/2018 [32]. Bread wheat can strongly adapt to different climates, and one of the key factors of this characteristic is the allohexaploid genome structure, which originates from two polyploidization events [33]. Allotetraploid T. turgidum (AABB), the ancestor of T. turgidum ssp. durum, is initially generated from the cross between T. urartu (AA) and Aegilops speltoides (SS) [34]. T. turgidum (AABB) subsequently crossed with A. tauschii (DD), and the ancestral allohexaploid T. aestivum (AABBDD) was finally obtained [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. As a kind of allohexaploid plant species with 21 chromosomes, bread wheat has three homologous subgenomes (A, B, and D), and each subgenome contains seven chromosomes, but it genetically behaves like a diploid species [40]. The large and repetitive genome of wheat makes it very difficult to analyze the gene family on the basis of the wheat genome.

In this work, we identified TaWD40 proteins in wheat at a genome-wide level, including their number, chromosomal distribution, gene structure, gene duplication, and evolutionary relationship of family members. We analyzed the syntenic relationships of WD40 proteins between wheat and rice. We also examined the tissue-specific expression and expression profiles of TaWD40s under biotic and abiotic stresses by using the public RNA-seq data. Our qRT-PCR results indicated the possible important roles of some TaWD40s during seed development. All above-mentioned results provided a basis for further functional characterization of WD40 proteins in wheat.

Results

Identification of WD40 proteins in wheat

To identify the TaWD40s in wheat, the hmmsearch program (HMMER3.0 package) was performed against the protein databases (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0) by using the hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles of the WD40 domain (PF00400) as queries [41, 42]. After the redundant transcripts were removed, all of the candidates were examined via the HMMER website [43] and SMART website [44] to search for the WD40 domain. All of the published TaWD40 proteins on NCBI were screened, and these proteins were included in our result. A total of 743 WD40 proteins were obtained in wheat. For convenience, their corresponding genes were numbered from TaWD40–1 to TaWD40–743 based on their positions located on 21 chromosomes (Additional file 1: Table S1), from the top to the bottom, from 1 to 7, and in the order of A, B, and D [45].

In silico analysis revealed that TaWD40s varied largely in length and physicochemical properties. Their lengths ranged from 154 to 3576 amino acid residues. In terms of physicochemical properties (Additional file 1: Table S1), EXPASY analysis indicated that the TaWD40 protein sequences differed greatly in isoelectric point (pI, ranging from 4.23 to 10.99) and molecular weight (MW, 16.9–397.2 kDa).

Chromosomal distribution and gene structure

The position of each TaWD40 was determined by mapping its sequence to the corresponding chromosome of wheat cv. Chinese Spring (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0) via the BLAST program. The 743 TaWD40s were assigned to 21 wheat chromosomes. The positions of TaWD40s (Fig. 1) represented the relative locations in the genome instead of their real positions, considering that the length of each gap was directly set to 100 bp during sequence assembly. TaWD40s were extensively and unevenly distributed on the chromosomes. Subgenomes A, B, and D had 240, 261, and 242 TaWD40s, respectively. Each of chromosomes 3B and 7B had 49 genes, which had the largest number of TaWD40s. By contrast, chromosomes 6A and 6D had the least number of TaWD40s, and each had 23 genes (Fig. 1a). The distributions of TaWD40s showed that some genes accumulated on particular chromosomes. Numerous TaWD40s were distributed at the bottom of chromosomes, especially in 4A, 7A, 7B, 5D, and 7D. Relatively high densities were also detected at the top of chromosomes 4B and 4D. While relatively low densities of TaWD40s were mostly found at the top of chromosomes 6B, 1D, and 6D. Previous studies also demonstrated the widespread and uneven distribution features of WD40s on chromosomes in animals and plants [25, 26, 28, 29, 31].

Genomic distributions of 743 TaWD40s on 21 wheat chromosomes. (a) Numbers of TaWD40s on each wheat chromosome. (b) “TaWD40 distribution map” on 21 wheat chromosomes. Tandemly duplicated genes are marked by red boxes. The scale bar is shown in megabase (Mb). The picture was drawn by MapInspect. (c) Segmentally duplicated TaWD40s in wheat subgenomes A, B, and D. Arabic numerals represent the gene numbers of TaWD40s, and the different color lines indicate the synteny of WD40. The picture was drawn with Circos

To gain insights into the structures of TaWD40s, we analyzed their exon and intron organizations. The number of exons and introns in TaWD40s widely varied. The maximum number of exons contained in TaWD40s was 39 (38 introns), but only 1 exon and no intron existed in some genes. Among the TaWD40s, the genes containing 1 and 9 exons had the maximum number of members (59 genes), and 7–14 exons were present in about half of TaWD40s (Additional file 2: Figure S1, Additional file 1: Table S1).

Gene duplication and genome synteny

Tandem and segmental duplication are key factors in gene family evolution to generate new gene members. In comparison with genomes in other grasses, inter- and intra-chromosomal duplications in wheat are more commonly detected through interspecific whole-genome analysis [33]. Thus, we investigated the segmental and tandem duplication events in the WD40 gene family in wheat. In our study, 39 pairs of genes among 743 TaWD40s were identified as tandem duplications (Fig. 1b, Additional file 1: Table S2), and 46 pairs of genes might be related to segmental duplication events (Fig. 1c, Additional file 1: Table S3). Roughly one-to-one correspondences of these tandem duplication and segmental duplication events were observed in wheat A, B, and D subgenomes, that is, tandem duplication or segmental duplication events often occurred at the same locations in the three subgenomes of wheat.

The substitution rate of nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) is the basis for evaluating the positive selection pressure of duplication events, where Ka/Ks = 1 denoted neutral selection, Ka/Ks < 1 indicated purifying selection, and Ka/Ks > 1 referred to positive selection. KaKs Calculator 2.0 was used to calculate Ka/Ks of duplicated TaWD40s. Ka/Ks of tandem duplications ranged from 0.03 to 1.22, and the mean value was 0.43, but the ratio of TaWD40–273/TaWD40–274 was greater than 1 (Additional file 1: Table S2). Ka/Ks of 46 pairs of segmental duplication genes varied from 0.028 to 1.66, and the average was 0.39 (Additional file 1: Table S3). TaWD40–463/TaWD40–492, TaWD40–364/TaWD40–443, and TaWD40–547/TaWD40–628 had Ka/Ks > 1, that is, 1.10571, 1.32411, and 1.66471, respectively. Therefore, duplication events played a pivotal role in the evolution of TaWD40s.

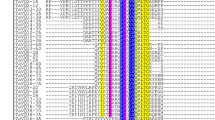

The syntenic relationships of WD40s between wheat and rice were analyzed to further study the evolution of WD40s. A total of 123 OsWD40s were identified to have synteny with TaWD40s (Fig. 2, Additional file 1: Table S4). The sequence similarities between the identified TaWD40s, OsWD40s, and AtWD40s were preliminarily examined by BLATP to identify the orthologous genes of TaWD40s in rice and Arabidopsis (Additional file 1: Table S5). For example, TaWD40–123, TaWD40–352, and TaWD40–605 are identified as TaGB1 and orthologous to OsWD40–80 and At4G34460.1. TaWD40–188 and TaWD40–439 are orthologous to OsWD40–50, which are identified as TaTTG1 [46].

Syntenic relationships of WD40s between wheat (Ta) and rice (Os). The positions of all of the WD40s are depicted in the three subgenomes of wheat (red bands of A subgenome, blue bands of B subgenome, and green bands of D subgenome), rice (yellow bands). The Arabic numerals represent the gene numbers of WD40 in wheat and rice. The different color lines indicate the synteny of WD40 among wheat and rice. The picture was drawn with Circos

Classification and phylogenetic analysis of wheat WD40 proteins

The protein sequences of the 743 identified TaWD40s were used to construct a phylogenetic tree via the neighbor-joining (N-J) method to analyze the evolutionary relationships of the WD40 family in wheat. In Fig. 3, the TaWD40s were divided into 5 major distinct clusters (Clusters I–V) containing 124, 173, 137, 89, and 220 proteins, respectively. The 743 TaWD40s were grouped into 11 subfamilies based on their domain compositions (Additional file 1: Table S1). The 478 TaWD40s containing only WD40 domains were classified as subfamily A. The 265 remaining TaWD40s comprising other additional domains were grouped into subfamilies B–K (Table 1).

Spatial and temporal expression profiles of TaWD40s

WD40 proteins have complicated structures and diverse functions, and studying their functions is difficult because of the allopolyploid characters of bread wheat. Their gene expression profile could provide useful information to reveal gene functions. The public RNA-seq data obtained from the expVIP website were used to analyze the spatial and temporal expression profiles of TaWD40s in wheat. The expression profiles covered 15 tissues during the entire life cycle of wheat (cv. Chinese Spring).

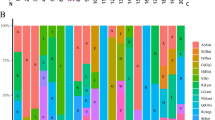

The hierarchical cluster figure was generated by using the log2 of transcript per million (TPM) values of the 743 TaWD40s. The tissue expression profiles of TaWD40s were clustered into 6 groups (Groups I–VI) based on their expression characteristics (Fig. 4, Additional file 1: Table S6). Group I consisted of 164 genes, and the average expression levels in TPM ranged from 3.62 to 14.29 (average value 6.51). Group II comprised 101 genes with relatively high expression levels, and their average expression levels varied from 8.67 to 25.19 (average value 13.44). Group III was composed of 198 genes with low expression levels, and their average expression levels ranged from 1.61 to 6.29 (average value 3.58). Group IV included 232 genes that were barely expressed in almost all of the tested tissues, and their average value was 0.79. Group V had 18 genes with relatively low expression levels in most tissues except in some individual tissues. Group VI contained the 30 remaining genes with high expression levels in all of the 15 tissues, and their expression levels ranged from 24.80 to 121.89 with an average value of 44.73.

Spatial and temporal expression profiles of TaWD40. The heatmap was generated on the basis of the RNA-seq data and drawn with the R program. The color scale is shown at the upper left of the figure represents Log2 of transcript per million (TPM). Higher expression levels are shown in red, and lower expression levels are denoted in blue

The expression profiles of TaWD40s are similar to OsWD40s [31], and multiple expression characteristics demonstrate the diverse functions of some TaWD40s in wheat growth and development. For example, TaWD40–289 belonging to Group I was remarkably and highly expressed in roots and stems but was relatively weakly expressed in other tissues, implying that this gene might play an important role in root and stem development. Group IV members, such as TaWD40–21, TaWD40–263, and TaWD40–522 (homologous genes on subgenomes A, B, and D), almost had no expression in all of the 15 analyzed tissues, and they might participate in some special physiological and biological processes under certain conditions. Group VI genes, such as TaWD40–82, TaWD40–332, and TaWD40–589 (homologous genes on subgenomes A, B, and D), which were identified as guanine nucleotide-binding protein beta subunit-like genes, might perform housekeeping functions and had the highest average expression levels in all of the tissues among 743 analyzed genes.

Expression profiles of TaWD40s under biotic and abiotic stresses

The RNA-seq data were downloaded from the expVIP website based on IWGSC 1.0 annotation. The differential expression of TaWD40s under biotic stresses (powdery mildew pathogen and stripe rust pathogen infection) and abiotic stresses (cold, heat and drought) was analyzed, and their MA plots were drawn (Additional file 2: Figure S2, Additional file 1: Table S7). The upregulated and downregulated TaWD40s were also counted under different stresses (Table 2). Our results revealed 92 significantly upregulated TaWD40s and 73 significantly downregulated TaWD40s in wheat shoots at the three-leaf stage under cold stress. Additionally, the number of differentially expressed TaWD40s under heat stress was more than that under drought stress. More TaWD40s were downregulated compared with the upregulated ones. The number of stress-responsive TaWD40s under 6 h of treatment was more than that under 1 h of treatment. Furthermore, the responses of TaWD40s to biotic stresses mainly occurred at the early stage of pathogen infection, and the number of differentially expressed genes gradually decreased as time progressed. The number of the upregulated TaWD40s exposed to powdery mildew pathogen E09 was higher than that of the upregulated TaWD40s infected by stripe rust pathogen CYR31.

Expression profiles of TaWD40s during seed development

Some WD40s are essential for seed development; for instance, TTG1 participates in the pigmentation of testa and the development of trichomes in A. thaliana [47, 48] and sorghum [49]. The tissue expression of TaWD40s indicates that many genes are specifically expressed in spikes and grains, suggesting their important roles in wheat seed development. Hence, 26 TaWD40s were randomly selected from the 5 distinct clusters of the phylogenetic tree to analyze their expression characteristics during wheat seed development through qRT-PCR.

We sampled the developing seeds every 4 days after anthesis for a total of 7 sampling times. Among the 26 selected TaWD40s (Fig. 5, Additional file 2: Figure S3, Additional file 1: Table S8), the expression levels of TaWD40–129 and TaWD40–150 increased rapidly during the early stages of seed development and gradually decreased with seed maturity. Furthermore, 11 TaWD40s (TaWD40–1, TaWD40–18, TaWD40–26, TaWD40–39, TaWD40–78, TaWD40–135, TaWD40–162, TaWD40–183, TaWD40–186, TaWD40–222, and TaWD40–450) shared the same expression pattern; that is, their expression levels were downregulated at the early stages of seed development, but their expression levels increased gradually 12 days after anthesis. The expression levels of TaWD40–38, TaWD40–48, TaWD40–73, TaWD40–74, TaWD40–81, TaWD40–83, TaWD40–85, TaWD40–148, TaWD40–185, TaWD40–223, and TaWD40–669 continually decreased from relatively high expression levels (4 days after anthesis) during wheat seed development. The expression levels of TaWD40–7 and TaWD40–86 fluctuated and had no obvious expression trends.

Expression profiles of 26 selected TaWD40s in the seed development of T. aestivum L. cv. Chinese Spring. Y-axis, relative expression levels; X-axis, days after anthesis. The error bars represent standard deviation (S.D.) calculated from three replications. The gene expression levels are normalized to the internal control of TaActin

Discussion

Expansions of WD40s in wheat

WD40 family expansion is a result of tandem and segmental duplications. In our study, tandem duplications led to 5.2% (39 of 743) of newly produced genes, and segmental duplication events contributed to 6.2% (46 of 743) of the newly generated genes. Different subfamilies had various effects on wheat gene expansion events. In particular, tandem duplications mainly originated from subfamily A (41%, 16 of 39) and subfamily G (46%, 18 of 39) grouped in Cluster II. Segmental duplication gene pairs were mainly from subfamily A (65%, 30 of 46). The homologous genes of TaWD40–103 and TaWD40–135 located on subgenome A were TaWD40–627 and TaWD40–640 on subgenome D, and these two pairs of genes were identified as segmental duplication genes belonging to subfamilies A and B, respectively. The N-terminals of TaWD40–103 and TaWD40–627 had similar multiple mutations, and the LisH domain could not be formed. As such, they were grouped into subfamily A. Thus, duplication and homologous recombination were the major primary driving forces of the evolution of the TaWD40 family. Allopolyploidy and high-level gene duplication (inter and intra-chromosomal duplications) provided a large genome with numerous functional genes for the adaptation of wheat in complicated various environments.

Expression profile analysis of TaWD40s

Tissue expression profile analysis revealed that many TaWD40s were differentially expressed in spike and seed development (Fig. 4), indicating that TaWD40s might participate in seed development. TaWD40–161 was identified as the orthologous protein of Arabidopsis JINGUBANG, which is a negative regulator of pollen germination [50]. TaWD40–161 was specifically and highly expressed in spikes during anthesis but was almost not expressed in other tissues. TaWD40–161 might play a pivotal role in anther development. The qRT-PCR results verified the special expression profiles of some TaWD40s during seed development (Fig. 5). The RNA-seq data of tissue expression profile analysis exhibited the expression levels of TaWD40s in wheat seed grown for 2, 14, and 30 days after anthesis. Interestingly, the expression levels of almost all of TaWD40s in the wheat seed 14 days after anthesis were lower than those in the wheat seed 2 and 30 days after anthesis, and this expression characteristic was confirmed by the qRT-PCR results. The expression levels of most selected TaWD40s gradually decreased at the early stage of wheat seed development. The expression levels of TaWD40–135, TaWD40–26, and TaWD40–162 decreased and then significantly increased during wheat seed development. TaWD40–135 (containing the LisH domain at N-terminus and the bromodomain at C-terminus), TaWD40–26 (containing the NLE domain), and TaWD40–162 (containing BEACH domains) might participate in wheat seed development. TaWD40–1 and TaWD40–78 were identified as RAE1-like protein, which is an essential mitotic checkpoint regulator [51].

WD40s participate in responses to various abiotic stresses [52,53,54,55]. For instance, TaWD40D (identified as TaWD40–614 in this work), which is homologous to TaWD40–114 and TaWD40–362 (Additional file 1: Table S9-S11), functions as a positive regulator of plant responses to salt and osmotic stresses [53]. In our study, the upregulated expression of TaWD40–362 under cold, heat, and drought stresses validated that it was implicated in multiple abiotic stress responses. RNA-seq data analysis revealed that a number of TaWD40s responded to multiple abiotic stresses, and the number of the upregulated genes was larger than that of the downregulated ones. The number of responsive TaWD40s remarkably increased as the treatment time was extended. Conversely, only a few TaWD40s significantly responded to biotic stresses at the early stage of treatments.

Conclusions

In this study, 743 TaWD40s distributed on subgenomes A, B, and D were identified and analyzed on a genome-wide scale. All of the genes were distributed extensively and unevenly on every chromosome of each subgenome, but they had one-to-one homology relationship at a subgenome level. Phylogenetic analysis and conserved domain prediction revealed that 743 TaWD40s were arranged in 5 main distinct clusters and grouped into 11 subfamilies. Synteny analysis indicated that WD40s in wheat were highly homologous to those in rice. Sequence analysis suggested that segmental duplication and tandem duplication were the major driving forces of TaWD40 family evolution. Homologous recombination was also essential for gene evolution.

The expression profiles of TaWD40s were analyzed by using RNA-seq data, and the results indicated that most TaWD40s were expressed in the entire life cycle of wheat. Some tissue-specific expression genes might participate in the development of spikes and seeds. The qRT-PCR analysis confirmed the crucial roles of some TaWD40s in wheat seed development. The expression profiles of TaWD40s under different stresses indicated that a large number of TaWD40s were involved in responses to stresses of cold, heat, drought, and powdery mildew infection in wheat. Our study provided a reference for the further functional investigation of these selected candidate TaWD40 proteins.

Methods

Identification of TaWD40 proteins

The HMM profile of the WD40 domain (PF00400) was downloaded from Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/family/PF00400) to identify all of the WD40 proteins in wheat, and the whole genome sequence of wheat cv. Chinese Spring (IWGSC RefSeqv1.0) was downloaded from URGI (https://wheat-urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Seq-Repository/Assemblies). All of the WD40 proteins were identified by using the default settings of hmmsearch program of the HMMER3.0 software (http://hmmer.org/download.html), and the redundant sequences among them were deleted by utilizing the perl program. The SMART website (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) [44] and the HMMER website (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/hmmer/) [43] were used to confirm all the TaWD40s containing WD40 repeat. In addition to the WD40 domain, other conserved motifs in these genes were identified.

Structural analysis of TaWD40s

The coding sequence (CDS), protein sequence, and genomic sequence of the identified TaWD40s were obtained from IWGSC RefSeq v1.0 (https://wheat-urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Seq-Repository/Assemblies). An exon/intron map was drawn by uploading their CDS and genomic sequences to Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS 2.0, http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) [56]. Theoretical pI and MW were analyzed (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/) [57, 58].

Chromosomal distribution, gene duplication, and synteny analysis

The location of each WD40 on the 21 wheat chromosomes was mapped to IWGSC RefSeq v1.0 (cv. Chinese_Spring) by using Blast programs (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) [59], and a physical map was drawn with MapInspect. The following criteria were used to identify the tandem duplication events of TaWD40s: 1) alignment length was over 80% of the full length of the gene, 2) aligned region had an identity over 80%, and 3) no genes were inserted between them. Segmental duplication was defined as follows: 1) alignment length was longer than 1 kb, and 2) aligned region had an identity of > 90% [60,61,62,63]. The segmental duplications in three subgenomes were separately identified, considering that wheat is a hexaploid. MCScanX was used to analyze the synteny of WD40s between wheat and rice [64, 65], and figures were drawn with Circos v0.69 [66]. Ka/Ks was calculated with KaKs Calculator 2.0 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/kakscalculator2/) [67].

Phylogenetic analysis

The WD40 protein sequences of wheat were imported to Clustal X2 (http://www.clustal.org/clustal2/) [68], and complete alignment was conducted by using the default settings. The alignment results were imported to MEGA7 (https://www.megasoftware.net/) [69] to construct an unrooted phylogenetic tree by using N-J method with a bootstrap of 1000 replicates.

Expression profile analysis

The RNA-seq data were downloaded from the expVIP website (http://www.wheat-expression.com/) to analyze the spatial and temporal expression profiles of WD40s in wheat [70, 71]. The study title was “choulet_URGI”. Two biological replicates with 15 tissue types of wheat (cv. Chinese Spring) were used. A heatmap was drawn by using R program (https://www.R-project.org/) gplots package. The RNA-seq data (study title “SRP043554,” “SRP045409,” and “SRP041017”) were downloaded from the expVIP website to examine the expression profiles of TaWD40s under different stresses (cold, heat and drought, powdery mildew pathogen, and stripe rust pathogen). R program DESeq2 package was utilized to evaluate the differential expression of TaWD40s under stresses and to draw MA plots.

For qRT-PCR analysis, the seeds of wheat cv. Chinese Spring were sampled every 4 days after anthesis for 7 continuous times. Target materials were quick frozen in liquid nitrogen and then transferred to a refrigerator at − 80 °C. Total RNA was collected with a plant tissue total RNA extraction kit (Zomanbio, Beijing, China), and the first cDNA chain was synthesized using a FastKing RT kit with gDNase (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The qRT-PCR analysis was performed using AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) on a qRT-PCR machine (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The primer sequences used for the expression profile analysis are presented in Additional file 1: Table S8. The wheat housekeeping gene TaActin (accession No. AB181991.1) was used as a reference gene.

Change history

29 November 2018

Following the publication of this article [1], the authors reported the following errors:

Abbreviations

- BCAS3:

-

Breast carcinoma amplified sequence 3

- CAF1:

-

CCR4-associated factor 1

- CDS:

-

coding sequence

- DDB1:

-

DNA damage binding protein 1

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- GSDS:

-

Gene Structure Display Server

- HMM:

-

The hidden Markov model

- IWGSC:

-

The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium

- Ka:

-

non-synonymous

- Ks:

-

synonymous

- MW:

-

Molecular weight

- N-J:

-

Neighbor-Joining

- padj:

-

adjusted p value

- pI:

-

Isoelectric point

- TPM:

-

transcript per million

References

Stirnimann CU, Petsalaki E, Russell RB, Müller CW. WD40 proteins propel cellular networks. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:565–74.

Neer EJ, Schmidt CJ, Nambudripad R, Smith TF. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature. 1994;371:297–300.

Fong HK, Hurley JB, Hopkins RS, Miake-Lye R, Johnson MS, Doolittle RF, et al. Repetitive segmental structure of the transducin beta subunit: homology with the CDC4 gene and identification of related mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2162–6.

Lambright DG, Sondek J, Bohm A, Skiba NP, Hamm HE, Sigler PB. The 2.0 Å crystal structure of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature. 1996;379:311–9.

Wall MA, Coleman DE, Lee E, Iñiguez-Lluhi JA, Posner BA, Gilman AG, et al. The structure of the G protein heterotrimer Giα1β1γ2. Cell. 1995;83:1047–58.

Andrade MA, Perez-Iratxeta C, Ponting CP. Protein repeats: structures, functions, and evolution. J Struct Biol. 2001;134:117–31.

Wu X, Chen R, Gao Y, Wu Y. The effect of asp-his-Ser/Thr-Trp tetrad on the thermostability of WD40-repeat proteins. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10237–45.

Janda L, Tichy P, Spizek J, Petricek M. A deduced Thermomonospora curvata protein containing serine/threonine protein kinase and WD-repeat domains. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1487–9.

Hu X, Li T, Wang Y, Xiong Y, Wu X, Zhang D, et al. Prokaryotic and highly-repetitive WD40 proteins: a systematic study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10585.

Li T, Chen X, Garbutt KC, Zhou P, Zheng N. Structure of DDB1 in complex with a paramyxovirus V protein: viral hijack of a propeller cluster in ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2006;124:105–17.

Hattendorf DA, Andreeva A, Gangar A, Brennwald PJ, Weis WI. Structure of the yeast polarity protein Sro7 reveals a SNARE regulatory mechanism. Nature. 2007;446:567–71.

Xu C, Min J. Structure and function of WD40 domain proteins. Protein Cell. 2011;3:202–14.

Juhász T, Szeltner Z, Fülöp V, Polgár L. Unclosed β-propellers display stable structures: implications for substrate access to the active site of prolyl oligopeptidase. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:907–17.

Fulop V, Bocskei Z, Polgar L. Prolyl oligopeptidase: an unusual beta-propeller domain regulates proteolysis. Cell. 1998;94:161–70.

Reubold TF, Wohlgemuth S, Eschenburg S. Crystal structure of full-length Apaf-1: how the death signal is relayed in the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Structure. 2011;19:1074–83.

Zou H, Henzel WJ, Liu X, Lutschg A, Wang X. Apaf-1, a human protein homologous to C. Elegans CED-4, participates in cytochrome c-dependent activation of caspase-3. Cell. 1997;90:405–13.

Migliori V, Müller J, Phalke S, Low D, Bezzi M, Mok WC, et al. Symmetric dimethylation of H3R2 is a newly identified histone mark that supports euchromatin maintenance. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:136–44.

Margueron R, Justin N, Ohno K, Sharpe ML, Son J, Drury WJ III, et al. Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature. 2009;461:762–7.

Suganuma T, Pattenden SG, Workman JL. Diverse functions of WD40 repeat proteins in histone recognition. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1265–8.

Higa LA, Wu M, Ye T, Kobayashi R, Sun H, Zhang H. CUL4–DDB1 ubiquitin ligase interacts with multiple WD40-repeat proteins and regulates histone methylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1277–83.

Jennings BH, Pickles LM, Wainwright SM, Roe SM, Pearl LH, Ish-Horowicz D. Molecular recognition of transcriptional repressor motifs by the WD domain of the Groucho/TLE corepressor. Mol Cell. 2006;22:645–55.

Znaidi S, Pelletier B, Mukai Y, Labbe S. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe corepressor Tup11 interacts with the iron-responsive transcription factor Fep1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9462–74.

Wakasugi M, Kawashima A, Morioka H, Linn S, Sancar A, Mori T, et al. DDB accumulates at DNA damage sites immediately after UV irradiation and directly stimulates nucleotide excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1637–40.

Chen R, Miettinen PJ, Maruoka EM, Choy L, Derynck R. A WD-domain protein that is associated with and phosphorylated by the type II TGF-β receptor. Nature. 1995;377:548–52.

He S, Tong X, Han M, Hu H, Dai F. Genome-wide identification and characterization of WD40 protein genes in the silkworm, bombyx mori. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:527.

Zou XD, Hu XJ, Ma J, Li T, Ye ZQ. Genome-wide analysis of WD40 protein family in human. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39262.

Salih H, Gong W, Mkulama M, Du X. Genome-wide characterization, identification, and expression analysis of the WD40 protein family in cotton. Genome. 2018;61:539–47.

Mishra AK, Muthamilarasan M, Khan Y, Parida SK, Prasad M. Genome-wide investigation and expression analyses of WD40 protein family in the model plant foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.). PLoS One. 2014;9:e86852.

Li Q, Zhao P, Li J, Zhang C, Wang L. Genome-wide analysis of the WD-repeat protein family in cucumber and Arabidopsis. Mol Gen Genomics. 2014;289:103–24.

van Nocker S, Ludwig P. The WD-repeat protein superfamily in Arabidopsis: conservation and divergence in structure and function. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:50.

Ouyang Y, Huang X, Lu Z, Yao J. Genomic survey, expression profile and co-expression network analysis of OsWD40 family in rice. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:100.

FAO Cereal Supply and Demand Brief. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2018. http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/csdb/en/. Accessed 5 Jul 2018.

IWGSC TIWG. A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) genome. Science 2014;345:1251788.

Petersen G, Seberg O, Yde M, Berthelsen K. Phylogenetic relationships of Triticum and Aegilops and evidence for the origin of the a, B, and D genomes of common wheat (Triticum aestivum). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;39:70–82.

Ling HQ, Ma B, Shi X, Liu H, Dong L, Sun H, et al. Genome sequence of the progenitor of wheat a subgenome Triticum urartu. Nature. 2018;557:424–8.

Choulet F, Alberti A, Theil S, Glover N, Barbe V, Daron J, et al. Structural and functional partitioning of bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science. 2014;345:1249721.

Marcussen T, Sandve SR, Heier L, Spannagl M, Pfeifer M, Jakobsen KS, et al. Ancient hybridizations among the ancestral genomes of bread wheat. Science. 2014;345:1250092.

Pfeifer M, Kugler KG, Sandve SR, Zhan B, Rudi H, Hvidsten TR, et al. Genome interplay in the grain transcriptome of hexaploid bread wheat. Science. 2014;345:1250091.

Salamini F, Özkan H, Brandolini A, Schäfer-Pregl R, Martin W. Genetics and geography of wild cereal domestication in the near east. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:429–41.

Martinez-Perez E, Shaw P, Moore G. The Ph1 locus is needed to ensure specific somatic and meiotic centromere association. Nature. 2001;411:204–7.

Eddy SR. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–63.

Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D222–30.

Finn RD, Clements J, Arndt W, Miller BL, Wheeler TJ, Schreiber F, et al. HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W30–8.

Letunic I, Bork P. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D493–6.

Li X, Gao S, Tang Y, Li L, Zhang F, Feng B, et al. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analyses of bZIP transcription factors in wheat and its relatives and expression profiles of anther development related TabZIP genes. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:976.

Miller JC, Chezem WR, Clay NK. Ternary WD40 repeat-containing protein complexes: evolution, composition and roles in plant immunity. Front Plant Sci. 2016;6:1108.

Li S. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis: fine-tuning of the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;9:e27522.

Larkin JC, Walker JD, Bolognesi-Winfield AC, Gray JC, Walker AR. Allele-specific interactions between ttg and gl1 during trichome development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1999;151:1591–604.

Wu Y, Li X, Xiang W, Zhu C, Lin Z, Wu Y, et al. Presence of tannins in sorghum grains is conditioned by different natural alleles of Tannin1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10281–6.

Ju Y, Guo L, Cai Q, Ma F, Zhu QY, Zhang Q, et al. Arabidopsis JINGUBANG is a negative regulator of pollen germination that prevents pollination in moist environments. Plant Cell. 2016;28:2131–46.

Babu JR, Jeganathan KB, Baker DJ, Wu X, Kang-Decker N, van Deursen JM. Rae1 is an essential mitotic checkpoint regulator that cooperates with Bub3 to prevent chromosome missegregation. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:341–53.

Zhang D, Wang Y, Shen J, Yin J, Li D, Gao Y, et al. OsRACK1A, encodes a circadian clock-regulated WD40 protein, negatively affect salt tolerance in rice. Rice. 2018;11:45.

Kong D, Li M, Dong Z, Ji H, Li X. Identification of TaWD40D, a wheat WD40 repeat-containing protein that is associated with plant tolerance to abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:395–410.

Alexandre C, Möller-Steinbach Y, Schönrock N, Gruissem W, Hennig L. Arabidopsis MSI1 is required for negative regulation of the response to drought stress. Mol Plant. 2009;2:675–87.

Liu WC, Li YH, Yuan HM, Zhang BL, Zhai S, Lu YT. WD40-REPEAT 5a functions in drought stress tolerance by regulating nitric oxide accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40:543–52.

Hu B, Jin J, Guo A, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296–7.

Bjellqvist B, Hughes GJ, Pasquali C, Paquet N, Ravier F, Sanchez JC, et al. The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:1023–31.

Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Sanchez JC, Williams KL, Appel RD, et al. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;112:531–52.

Ma J, Yang Y, Luo W, Yang C, Ding P, Liu Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MADS-box gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181443.

Zhao Q, Zhu Z, Kasahara M, Morishita S, Zhang Z. Segmental duplications in the silkworm genome. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:521.

Kong X, Lv W, Jiang S, Zhang D, Cai G, Pan J, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase in maize. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:433.

Leister D. Tandem and segmental gene duplication and recombination in the evolution of plant disease resistance gene. Trends Genet. 2004;20:116–22.

Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–5.

Tang H, Bowers JE, Wang X, Ming R, Alam M, Paterson AH. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science. 2008;320:486–8.

Wang Y, Tang H, DeBarry JD, Tan X, Li J, Wang X, et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e49.

Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–45.

Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom Proteom Bioinf. 2010;8:77–80.

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.

Ramírez-González RH, Borrill P, Lang D, Harrington SA, Brinton J, Venturini L, et al. The transcriptional landscape of polyploid wheat. Science. 2018;361:6089.

Borrill P, Ramirez-Gonzalez R, Uauy C. expVIP: a customizable RNA-seq data analysis and visualization platform. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:2172–86.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) for providing pre-publication access to the reference sequence of wheat, IWGSC RefSeq v1.0.

Funding

The work was supported by National Genetically Modified New Varieties of Major Projects of China (2016ZX08010004–004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31771418, 31,570,261) and Key Project of Hubei Province (2017AHB041).

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data for the genomics sequences is available in the URGI (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/download/iwgsc/IWGSC_RefSeq_Assemblies/v1.0/). The public RNA-seq data are available on expVIP website (http://www.wheat-expression.com/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GH, GY and RH designed the experiments. RH and JX carried out the experiment and analyzed the data. TG and XY performed the qRT-PCR experiments. JC and YZ participated in the data analysis. GH, GY, RH and JX conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Characteristic features of 743 TaWD40s. Table S2. KaKs ratios of tandemly duplicated TaWD40s. Table S3. KaKs ratios of segmentally duplicated TaWD40s. Table S4. Syntenic relationships of WD40s between wheat and rice. Table S5. Homologous WD40s among wheat, rice, and Arabidopsis. Table S6. The expression levels of TaWD40s for spatial and temporal expression profiles analysis. Table S7. Significantly and differentially expressed TaWD40s under biotic and abiotic stresses. Table S8. Primers used for qRT-PCR. Table S9. Amino acid sequences of 743 TaWD40s. Table S10. Coding sequences of 743 TaWD40s. Table S11. Corresponding table for homologous TaWD40s located on 21 wheat chromosomes. Table S12. Functional annotation of TaWD40s from IWGSC RefSeqv1.0. (ZIP 1478 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Exon/intron organizations of 743 TaWD40s. Solid yellow boxes and black lines indicate exons and introns, respectively. The scale is shown at the bottom of the figure. Figure S2. MA plots of differentially expressed TaWD40s under biotic and abiotic stresses. MA plots were generated with DESeq2 version 1.20.0. Points are highlighted in red when padj is less than 0.05, representing significantly and differentially expressed TaWD40s. Points falling outside of 2 to − 2 log fold are plotted as open triangles pointing either up or down. (a) Cold stress for 2 weeks, (b) Heat stress for 1 h, (c) Heat stress for 6 h, (d) Drought stress for 1 h, (e) Drought stress for 6 h, (f) Drought and heat stresses for 1 h, (g) Drought and heat stresses for 6 h, (h) Infection of powdery mildew pathogen (E09) for 24 h, (i) Infection of powdery mildew pathogen (E09) for 48 h, (j) Infection of powdery E09 for 72 h, (k) Infection of stripe rust pathogen (CYR31) for 24 h, (l) Infection of CYR31 for 48 h, and (m) Infection of CYR31 for 72 h. Figure S3. Standard and dissociation curves of qRT-PCR. (ZIP 9762 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, R., Xiao, J., Gu, T. et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of WD40 proteins in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Genomics 19, 803 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-5157-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-5157-0