Abstract

Background

Two common single nucleotide polymorphisms within the COL5A1 gene (SNPs; rs12722 C/T and rs3196378 C/A) have previously been associated with tendon and ligament pathologies. Given the high incidence of tendon and ligament injuries in elite rugby athletes, we hypothesised that both SNPs would be associated with career success.

Results

In 1105 participants (RugbyGene project), comprising 460 elite rugby union (RU), 88 elite rugby league athletes and 565 non-athlete controls, DNA was collected and genotyped for the COL5A1 rs12722 and rs3196378 variants using real-time PCR. For rs12722, the injury-protective CC genotype and C allele were more common in all athletes (21% and 47%, respectively) and RU athletes (22% and 48%) than in controls (16% and 41%, P ≤ 0.01). For rs3196378, the CC genotype and C allele were overrepresented in all athletes (23% and 48%) and RU athletes (24% and 49%) compared with controls (16% and 41%, P ≤ 0.02). The CC genotype in particular was overrepresented in the back and centres (24%) compared with controls, with more than twice the odds (OR = 2.25, P = 0.006) of possessing the injury-protective CC genotype. Furthermore, when considering both SNPs simultaneously, the CC–CC SNP-SNP combination and C–C inferred allele combination were higher in all the athlete groups (≥18% and ≥43%) compared with controls (13% and 40%; P = 0.01). However, no genotype differences were identified for either SNP when RU playing positions were compared directly with each other.

Conclusion

It appears that the C alleles, CC genotypes and resulting combinations of both rs12722 and rs3196378 are beneficial for rugby athletes to achieve elite status and carriage of these variants may impart an inherited resistance against soft tissue injury, despite exposure to the high-risk environment of elite rugby. These data have implications for the management of inter-individual differences in injury risk amongst elite athletes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Elite rugby athletes regularly experience high velocity collisions that lead to increasingly high injury occurrence rates that are likely to be a consequence of the increasing size and strength of the athletes [1,2,3,4]. This increased size and strength is likely to result in greater changes in momentum during player collisions, as well as during voluntary accelerations and decelerations. This has resulted in rugby union (RU) having one of the highest reported injury incidence rates in professional team sports [5]. Meta-analyses have shown that for every 1000 h, an elite RU athlete will experience approximately 81 injuries during match play and three during training, with the majority being ligament, tendon and muscle injuries of the lower limbs [6]. Indeed, in the most recent Rugby World Cup (2015) this rate of incidence was more than 90 injuries per 1000 h [7]. Furthermore, pooled data from 10 studies of elite rugby league (RL) athletes show that injury incidence is approximately twice (172 per 1000 h) that of RU [8]. Similar to RU, the majority of injuries in RL occur on the lower limbs, consisting mainly of sprains and strains [8]. Injury incidence differs across RU playing position, with elite back row players showing the highest rate among forwards and centres the highest among backs [7]. Therefore, investigating the molecular genetic components of these injuries, including in the context of playing positions that differ in terms of physiological characteristics [9, 10], match play demands [11] as well as genetically [12], may progress understanding towards greater individualisation of match play exposure and training load and mode, in order to reduce injury risk [13].

The collagen fibril, which consists predominately of type I collagen, is the primary structural component of tendons, ligaments and other non-cartilaginous connective tissues [14]. The formation and diameter of the collagen fibril is regulated by, amongst other molecules, the minor fibrillar type V collagen protein [15,16,17,18]. The type V collagen isoform comprises two α1(V) and one α2(V) chains, encoded by the COL5A1 and COL5A2 genes respectively [16, 19] and forms between 1 and 5% of total collagen content [18, 20]. The COL5A1 gene is the most explored genetic locus in relation to tendon and ligament injuries [21,22,23,24,25], while mutations in the COL5A1 gene have been identified in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a disease characterised by joint hypermobility, laxity and muscle hypotonia [26]. This results in irregularly large collagen fibrils within connective tissue [27] and is attributed to a reduced synthesis of collagen type V [17, 28].

Two common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, rs12722 C/T and rs3196378 C/A) located in the functional 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) COL5A1 gene on chromosome 9 have been associated with tendon [23] and ligament ([rs12722] [29]) injuries. Specifically, the CC genotype of the more extensively investigated rs12722 polymorphism has been previously associated with reduced risk of chronic Achilles tendinopathy (odds ratio (OR) = 0.42-AUS and OR = 0.38-SA, respectively; [23, 25]), anterior cruciate ligament injury in females (OR = 6.6; [22]) and lateral epicondylitis (OR = 1.4; [21]), suggesting a protective role of the C allele against injury. Although there are conflicting results [23, 30], our current understanding also suggests that the CC genotype and/or the C allele of rs3196378 would also have a protective role [31, 32]. Considering the high frequencies of tendon and ligament inquiries in elite rugby [6,7,8, 33], assessing these specific genetic variants may be of use in helping improve the management of injury risk in individual players.

Given the association of the two COL5A1 gene variants with injury risk, it is possible that possession of the risk alleles might reduce an individual’s ability to withstand exposure to the environment of competitive rugby without suffering more frequent injuries. Consequently, those individuals would be forced to miss training, selection and competitive events important for their career progression. Thus, athletes carrying the C allele at either or both rs12722 and rs3196378 might be at an advantage in terms of their ability to achieve success in elite competitive rugby and at a disadvantage in terms of their shorter-term and longer-term musculoskeletal health. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to investigate if COL5A1 rs12722 and rs3196378 genotype and allele frequencies differed between elite rugby athletes and a control population, and/or between playing positions. It was hypothesised that the COL5A1 rs12722 and rs3196378 injury-protective C alleles and/or CC genotypes would be overrepresented in elite rugby athletes compared with controls.

Methods

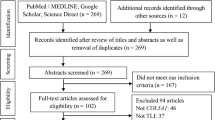

Participants

As part of the ongoing RugbyGene project [12, 13, 34], a total of 1105 individuals were recruited and gave written informed consent to participate in the present study. An a priori calculation for 80% power to detect a small effect size (w) of 0.1 required a sample of >785 participants. The sample comprised elite Caucasian male rugby athletes (n = 540; mean (standard deviation) height 1.85 (0.07) m, mass 101 (14) kg, age 29 (7) years) including 72% British, 16% South African, 7% Irish and 5% of other nationalities. Caucasian controls (68% male; n = 565; height 1.75 (0.10) m, mass 75 (13) kg, age 26 (11) years) included 86% British, 12% South African, 1% Irish and 1% of other nationalities recruited mainly during 2012–2016. Eight athletes competed in both elite RL and RU and were included in both groups that were analysed separately. Athletes were considered elite if they had competed regularly (> 5 matches) since 1995 in the highest professional league in the UK, Ireland or South Africa for RU and the highest professional league in the UK for RL. Of the RU athletes, 51.7% had competed at international level for a “High Performance Union” (Regulation 16, worldrugby.org) and 43.2% of RL had competed at international level. All data for the athlete group’s international status were confirmed as of 1st January 2017. Most participants in the current study were also participants in previous publications regarding variations in the ACTN3, ACE and FTO genes [12, 34].

Sample collection and genotyping

Description of all molecular procedures have previously been described in detail [12]. Briefly, blood (~70% of all samples), saliva (~25%) or buccal swab samples (~5%) were obtained via the following protocols. Blood from a superficial forearm vein was put into an EDTA tube and stored in sterile tubes at −20 °C until processing. Saliva samples were collected using Oragene DNA OG-500 collection tubes (DNA Genotek Inc., Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and stored at room temperature until processing. Sterile buccal swabs (Omni swab, Whatman, Springfield Mill, UK) were rubbed against the buccal mucosa of the cheek for approximately 30 s and the tips stored at −20 °C until processing. At MMU and Glasgow, DNA was stored at 4 °C following isolation performed using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit and standard spin column protocol (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK). In Cape Town, DNA was isolated from whole blood [35] and samples stored at −20 °C. At Northampton, DNA was isolated from whole blood using Flexigene kits (Qiagen), with the resulting samples stored at −20 °C.

Genotyping at all three centres was performed using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK) for both the COL5A1 rs12722 and rs3196378 variants. Our genotyping methods and quality control procedures have been fully described in our earlier study [12]. Minor adaptations were made to the volumes used in each assay mix depending on whether the DNA was obtained from buccal swabs or saliva/blood. PCR was performed on either a Chromo4 (Bio-Rad, Hertfordshire, UK) or StepOnePlus thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). Genotypes were called based on reporter dye intensity and visualized using cluster plots. The TaqMan assays included VIC and FAM dyes that for rs12722 indicated C and T alleles on the forward DNA strand, respectively. Thus, VIC/FAM were interpreted as: 5′-CACACCCA[C/T]GCGCCCCG-3′. For rs3196378, VIC and FAM dyes indicated C and A alleles on the forward DNA strand, respectively and were interpreted as: 5′-CCCACCCC[A/C]GCCCTGGC-3′. Genotype calling was 100% successful for both polymorphisms in the athlete samples. For rs12722, one of the 566 control samples was unsuccessful and, for rs3196378, 10 of the 566 control samples were unsuccessful. There was 100% agreement among reference samples genotyped in the three genotyping centres, i.e. Glasgow, Northampton and MMU laboratories.

Data analysis

SPSS for Windows version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) software was used to conduct Pearson’s Chi-square (χ2) tests to compare genotype (using three analysis models; additive, recessive and dominant), allele and inferred haplotype frequencies between athletes and controls, and between RU subgroups based on playing position and controls. With 80% statistical power, analyses of all genetic models in positional subgroups compared with controls (forwards, backs and back 3-centres) were able to detect a small-to-medium effect size (w) of 0.12. Multifactor Dimensionality Reduction (MDR; www.multifactordimensionalityreduction.org) software was used to calculate SNP-SNP epistasis interactions [36]. Haplotypes were inferred using SNPStats [37]. Sixty five tests were subjected to Benjamini-Hochberg (BH; [38]) corrections to control false discovery rate and corrected probability values are reported. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated to estimate effect size. CubeX online software (www.oege.org/software/cubex) was used to determine linkage disequilibrium statistics [39]. Alpha was set at 0.05.

Results

Genotype frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for both rs12722 and rs3196378 in the control (P ≥ 0.21) and athlete groups (RL, P ≥ 0.11; RU, P ≥ 0.754). There was no sexual dimorphism of genotype frequency for either rs12722 (P = 0.279) or rs3196378 (P = 0.374) within the control group. COL5A1 rs12722 and rs3196378 were in tight linkage disequilibrium for both controls (D′ = 0.902, r2 = 0.784) and all athletes (D′ = 0.877, r2 = 0.738). Athletes were taller and heavier (P < 0.05) but not older (P > 0.05) than controls.

rs12722

The CC genotype, proportion of C allele carriers and C allele were overrepresented in all athletes (21.1%, 73.3% and 47.2%, respectively) and RU athletes (22.0%, 73.3% and 47.6%) compared with controls (15.6%, 66.5% and 41.1%, Table 1 and Fig. 1 , P ≤ 0.01). Furthermore, the CC genotype, proportion of C allele carriers (Table 1 ) and C allele (Fig. 1 ) were overrepresented in the subgroups of RU forwards (22.1%, 71.5% and 46.8%) and backs (21.8%, 75.6% and 48.7%) compared with controls (15.6%, 66.5% and 41.1%). Additionally, of the RU subgroups, the back three and centres differed from controls and showed the greatest C allele and CC genotype frequency (50.8% versus 41.1% and 24.4% versus 15.6%, respectively, Table 1 and Fig. 1 , P ≤ 0.02). Compared with controls, those back three and centre players had 2.3 times the odds of possessing the CC genotype and 1.5 times the odds of possessing the C allele (Table 2 ).

Allele frequency of COL5A1 rs12722 ( a ) and rs3196378 ( b ) for control and athlete groups. Asterisks indicate a difference in allele frequency between the particular athlete group and controls. A single asterisk (*) designates P = 0.01 and a double asterisk (**) designates P = 0.02. RU, rugby union, RL rugby league. Eight athletes competed in both elite RL and RU and were included in both groups that were analysed separately

rs3196378

The CC genotype, proportion of C allele carriers and C allele were overrepresented in all athletes (23.1%, 73.3% and 48.4%) and RU athletes (23.9%, 73.3% and 48.6%) compared with controls (15.6%, 67.7% and 41.4%, Table 1 and Fig. 1 , P ≤ 0.02). Furthermore, CC genotype, proportion of C allele carriers (Table 1 ) and C allele (Fig. 1 ) were overrepresented in backs (21.8%, 75.1% and 48.5%) compared with controls (15.6%, 67.7% and 41.4%, P ≤ 0.02). Forwards also had higher CC genotype and C allele frequencies (25.5% and 48.7%; Table 1 and Fig. 1 ) and showed almost twice the odds of being CC genotype than carrying an A allele, compared with controls (Table 2 ). For the back three and centres group, 24.4% were CC genotype, 77.2% were C allele carriers and C allele frequency was 47.8% - all of which were greater than controls (P ≤ 0.02; Table 1 and Fig. 1 , OR = 2.25, Table 2 ).

Haplotype and SNP epistasis analysis

There was a greater frequency of the CC–CC SNP-SNP combination in all athletes (18.3%), RU athletes (18.9%), RU forwards (19.4%), RU backs (18.3%) and to the greatest extent the back three and centre group (20.3%; OR = 2.35; Table 2 ), compared with control (12.8%; all athlete comparisons with the control group were P = 0.01). Furthermore, C–C inferred haplotype frequencies were higher in all the athlete groups compared with controls, reflected by a greater frequency of the T–A inferred haplotype in the control group (P = 0.01; Fig. 2 ).

Inferred haplotype frequencies derived from COL5A1 rs12722 and rs3196378. RU, rugby union. Asterisks (*) indicate differences in inferred haplotype frequencies between the controls and each athlete group ( P = 0.01). Eight athletes competed in both elite RL and RU and were included in both groups that were analysed separately

Discussion

The present observations are the first to identify associations between COL5A1 rs12722 and rs3196378 polymorphisms and athlete status in a large cohort of elite rugby athletes. As hypothesised, the apparent injury-protective C allele and CC genotype, of both SNPs [23], were overrepresented in elite rugby athletes compared with controls. This association persisted across playing position, with the C allele being overrepresented in RU forwards and backs including the back three and centres group, compared with controls. Furthermore, when the two SNPs are combined, the CC–CC combination and C–C inferred allele combination showed similar overrepresentation in elite rugby athletes compared with controls.

The results provide an insight into the potential injury susceptibility of some elite rugby athletes. September et al. [23] identified a higher frequency of the CC genotype in asymptomatic controls for both rs12722 and rs3196378 compared with tendinopathy patients [23, 32]. Moreover, the rs12722 T allele has been associated with ligament injury [21, 22, 24, 40] and Achilles tendinopathy [23, 25] with the C allele again identified as protective in these studies, despite a lack of replication in another study [30]. Greater joint laxity has almost a 3-fold increase in risk of knee ligament rupture [41] and greater joint laxity has recently been associated with the rs12722 T allele in non-white females [40]. Collectively, these data suggest that the C allele of rs12722 and/or rs3196378 (or other variant(s) in strong LD with these SNPs) might be beneficial in protecting against tendon and ligament injuries. This is reflected in the present study showing greater C allele frequency in elite rugby athletes compared with controls. Based on these data, we propose that when exposed to the high-risk environment of rugby during training and especially during competitive matches, ceteris paribus, carriage of the C alleles at the rs12722 and rs3196378 loci provides both a shorter-term and longer-term advantage to rugby athletes in the form of reduced injury risk. Athletes with fewer and/or less severe injuries, all else being equal, will miss fewer matches, training and selection events and thus be more likely to progress towards elite status in their athletic careers compared with their peers.

The rs12722 CC genotype has also been related to a lower incidence of exercise-associated muscle cramping (EAMC) in Caucasian ironman and ultra-marathon athletes [42]. The authors hypothesised that this was due to similar mechanisms of reduced tendon injury susceptibility, in that rs12722 alters soft tissue structural and mechanical properties (tissue stiffness and thickening). Some recent findings might support this hypothesis, as greater tendon stiffness was associated with the rs12722 T allele in one study [43], however another study reported no association of rs12722 with tendon structural or mechanical properties [44]. These data suggest that in addition to the apparent protection from tendon and ligament injury, the greater frequencies of the C allele in elite rugby athletes might be protective against muscle cramping and possibly reduced tendon stiffness. Indeed, recent evidence from elite RL shows that over 70% of athletes experience EAMC per season and that history of cramping is the strongest predictor of future EAMC [45]. In contrast, the TT genotype has been associated with greater endurance running ability of Caucasian ironman triathletes (TT = 294 min, CC = 307 min; [46]). However, recent data show no association of rs12722 with either running economy or VȮ2max [47]. While endurance capacity is of value in elite rugby, the predominant focus of player selection and training programs is towards power, speed and strength - i.e. short-term, anaerobic performance [with notable differences between playing positions; 9, 10].

Limited data exist regarding COL5A1 genetic variation and team sport athletes. In a study of 73 soccer athletes, including some elite players, no rs12722 TT genotype individuals were identified (a potentially interesting observation but difficult to interpret because of the varied geographic ancestry of the athletes), but there was a tendency for more severe muscle injuries in the TC genotype group (P = 0.08), compared with CC [48]. Here, consistent with those observations, we show an overrepresentation of the protective C allele and CC genotype of both rs12722 and rs3196378, in addition to CC–CC SNP-SNP combination and C–C inferred allele combination in elite rugby athletes.

Some possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association of COL5A1 gene variants and soft tissue injury [31, 32]. Laguett et al. [32] have shown that the COL5A1 3′ UTR – where both rs12722 and rs3196378 are situated - affects mRNA stability. For both SNPs, the alleles associated with greater soft-tissue injury risk were associated with greater Hsa-miR-608 stability, which in turn may alter the Col5α1 protein secondary structure - proposed to play a role in type V collagen production [31]. This would suggest that C/T allele differences at rs12722 might alter the co-polymerisation of collagen type V and type I fibrils. However, to date, this has not been demonstrated experimentally and exactly how this may translate into functional properties is currently unknown. Nevertheless, it appears that the C allele and CC genotype of rs12722 and rs3196378 appear beneficial for rugby athletes to achieve elite status, probably through greater resistance to soft tissue injury. Interestingly, while most relevant investigations have focussed on rs12722, we show in a large cohort (total n = 1090) that strong linkage disequilibrium exists in both controls and athletes between rs12722 and rs3196378. As such, it is likely that the associations of rs12722 with tendon and ligament injuries would be similar for rs3196378. It is possible that combining genetic data from multiple gene variants associated with injury susceptibility, such as those presented here, with other indicators of injury risk and recovery during rehabilitation could be used to better manage the prevention and recovery from elite player injury in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have presented the first associations between COL5A1 3′ UTR rs12722 and rs3196378 and elite status within a large cohort of rugby athletes. The C alleles of both polymorphisms, separately and in combination, were overrepresented in all athletes, RU forwards, backs and in RU back three and centre players versus controls. We propose that rugby athletes possessing more C alleles at these two genetic loci are probably at a lower risk of injury, given their exposure to the high-risk environment of elite rugby. However, these data pertain to only two SNPs of many that may be relevant to soft tissue injury and interpretation of the present results should be in that context. Future investigations should seek to combine elite rugby genotype data such as these with injury incidence data during rugby matches and training. It will be important to establish whether inter-individual differences in injury risk, within a population that we demonstrate here appear to be at an overall lower genetic risk of tendon and ligament injury compared with non-athletes, nevertheless are associated with those same genetic loci.

Abbreviations

- 3′ UTR:

-

3′ untranslated region

- COL5A1 :

-

collagen type V α1

- COL5A2 :

-

collagen type V α2

- DNA:

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EAMC:

-

exercise-associated muscle cramping

- EDTA:

-

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- MDR:

-

multifactor dimensionality reduction

- miRNA:

-

micro ribonucleic acid

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RL:

-

rugby league

- RU:

-

rugby union

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphisms

References

Bradley WJ, Cavanagh BP, Douglas W, Donovan TF, Morton JP, Close GL. Quantification of training load, energy intake, and physiological adaptations during a rugby preseason: a case study from an elite eropean rugby union squad. J Stength Cond Res. 2015;29(2):534–44.

Sedeaud A, Vidalin H, Tafflet M, Marc A, Toussaint J. Rugby morphologies:“bigger and taller”, reflects an early directional selection. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2013;53(2):185–91.

Cunniffe B, Proctor W, Baker JS, Davies B. An evaluation of the physiological demands of elite rugby union using global positioning system tracking software. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(4):1195–203.

Owen NJ, Watkins J, Kilduff LP, Bevan HR, Bennett MA. Development of a criterion method to determine peak mechanical power output in a countermovement jump. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(6):1552–8.

Brooks JH, Kemp SP. Recent trends in rugby union injuries. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27(1):51–73.

Williams S, Trewartha G, Kemp S, Stokes KA. Meta-analysis of injuries in senior men’s professional rugby union. Sports Med. 2013;43(10):1043–55.

Fuller CW, Taylor A, Kemp SP, Raftery M. Rugby World Cup 2015: World Rugby injury surveillance study. Brit J Sports Med. 2016:In press.

King D, Gissane C, Clark T, Marshall SW. The incidence of match and training injuries in rugby league: a pooled data analysis of published studies. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2014;9(2):417–32.

Smart D, Hopkins WG, Quarrie KL, Gill N. The relationship between physical fitness and game behaviours in rugby union players. Eur J Sports Sci. 2014;14(supp 1):S8–S17.

Smart DJ, Hopkins WG, Gill ND. Differences and changes in the physical characteristics of professional and amateur rugby union players. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(11):3033–44.

Jones MR, West DJ, Crewther BT, Cook CJ, Kilduff LP. Quantifying positional and temporal movement patterns in professional rugby union using global positioning system. Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;15(6):488–96.

Heffernan SM, Kilduff LP, Erskine RM, Day SH, McPhee JS, McMahon GE, et al. Association of ACTN3 R577X but not ACE I/D gene variants with elite rugby union player status and playing position. Physiol Genomics. 2016;48(3):196–201.

Heffernan SM, Kilduff LP, Day SH, Pitsiladis YP, Williams AG. Genomics in rugby union: a review and future prospects. Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;15(6):460–8.

Imamura Y, Scott IC, Greenspan DS. The pro-α3 (V) collagen chain complete primary structure, expression domains in adult and developing tissues, and comparison to the structures and expression domains of the other types V and XI procollagen chains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(12):8749–59.

Birk DE, Fitch J, Babiarz J, Doane K, Linsenmayer T. Collagen fibrillogenesis in vitro: interaction of types I and V collagen regulates fibril diameter. J Cell Sci. 1990;95(4):649–57.

Wenstrup RJ, Florer JB, Brunskill EW, Bell SM, Chervoneva I, Birk DE, Type V. Collagen controls the initiation of collagen fibril assembly. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53331–7.

Sun M, Chen S, Adams SM, Florer JB, Liu H, Kao WW-Y, et al. Collagen V is a dominant regulator of collagen fibrillogenesis: dysfunctional regulation of structure and function in a corneal-stroma-specific Col5a1-null mouse model. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(23):4096–105.

Chanut-Delalande H, Bonod-Bidaud C, Cogne S, Malbouyres M, Ramirez F, Fichard A, et al. Development of a functional skin matrix requires deposition of collagen V heterotrimers. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(13):6049–57.

Malfait F, Wenstrup RJ, De Paepe A. Clinical and genetic aspects of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, classic type. Genet Med. 2010;12(10):597–605.

McLaughlin J, Linsenmayer T, Birk D, Type V. Collagen synthesis and deposition by chicken embryo corneal fibroblasts in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1989;94(2):371–9.

Altinisik J, Meric G, Erduran M, Ates O, Ulusal AE, Akseki D. The BstUI and DpnII variants of the COL5A1 Gene are associated with Tennis Elbow. 2015;43(7):1784–9.

Posthumus M, September AV, O’Cuinneagain D, van der Merwe W, Schwellnus MP, Collins M. The COL5A1 gene is associated with increased risk of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in female participants. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2234–40.

September AV, Cook J, Handley CJ, van der Merwe L, Schwellnus MP, Collins M. Variants within the COL5A1 gene are associated with Achilles tendinopathy in two populations. Brit J Sports Med. 2009;43(5):357–65.

O'Connell K, Knight H, Ficek K, Leonska-Duniec A, Maciejewska-Karlowska A, Sawczuk M, et al. Interactions between collagen gene variants and risk of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Eur J Sports Sci. 2015;15(4):341–50.

Mokone G, Schwellnus M, Noakes T, Collins M. The COL5A1 gene and Achilles tendon pathology. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(1):19–26.

Beighton P, Paepe AD, Steinmann B, Tsipouras P, Wenstrup RJ. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77(1):31–7.

Vogel A, Holbrook K, Steinmann B, Gitzelmann R, Byers P. Abnormal collagen fibril structure in the gravis form (type I) of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Lab Investig. 1979;40(2):201–6.

Malfait F, De Paepe A. Molecular genetics in classic Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet . 2005; 139 C(1):17–23.

Posthumus M, September AV, Keegan M, O’Cuinneagain D, Van der Merwe W, Schwellnus MP, et al. Genetic risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament ruptures: COL1A1 gene variant. Brit J Sports Med. 2009;43(5):352–6.

Brown KL, Seale KB, El Khoury LY, Posthumus M, Ribbans WJ, Raleigh SM, et al. Polymorphisms within the COL5A1 gene and regulators of the extracellular matrix modify the risk of Achilles tendon pathology in a British case-control study. Ahead of print: J Sports Sci; 2016.

Abrahams Y, Laguette MJ, Prince S, Collins M. Polymorphisms within the COL5A1 3′-UTR that alters mRNA structure and the MIR608 gene are associated with Achilles Tendinopathy. Ann Hum Genet. 2013;77(3):204–14.

Laguette M-J, Abrahams Y, Prince S, Collins M. Sequence variants within the 3′-UTR of the COL5A1 gene alters mRNA stability: implications for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. Matrix Biol. 2011;30(5):338–45.

Fuller CW, Taylor A, Raftery M. Epidemiology of concussion in men's elite rugby-7s (sevens world series) and rugby-15s (rugby world cup, junior world championship and rugby trophy, Pacific nations cup and English premiership). Brit J Sports Med. 2015;49(7):478–83.

Heffernan SM, Stebbings GK, Kilduff LP, Erskine RM, Day SH, Morse CI, et al. Fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene influences skeletal muscle phenotypes in non-resistance trained males and elite rugby playing position. BMC Genet. 2017;18(1):4.

Lahiri DK, Nurnberger JIA. Rapid non-enzymatic method for the preparation of HMW DNA from blood for RFLP studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(19):5444.

Moore JH, Gilbert JC, Tsai CT, Chiang FT, Holden T, Barney N, et al. A flexible computational framework for detecting, characterizing, and interpreting statistical patterns of epistasis in genetic studies of human disease susceptibility. J Theor Biol. 2006;241(2):252–61.

Sole X, Guino E, Valls J, Iniesta R, Moreno V. SNPStats: a web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(15):1928–9.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57(1):289–300.

Gaunt TR, Rodríguez S, Day IN. Cubic exact solutions for the estimation of pairwise haplotype frequencies: implications for linkage disequilibrium analyses and a web tool'CubeX. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8(1):428.

Bell RD, Shultz SJ, Wideman L, Henrich VC. Collagen gene variants previously associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury risk are also associated with joint laxity. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2012;4(4):312–8.

Uhorchak JM, Scoville CR, Williams GN, Arciero RA, Pierre PS, Taylor DC. Risk factors associated with noncontact injury of the anterior cruciate ligament a prospective four-year evaluation of 859 west point cadets. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):831–42.

O’Connell K, Posthumus M, Schwellnus MP, Collins M. Collagen genes and exercise-associated muscle cramping. Clin J Sport Med. 2013;23(1):64–9.

Kirk E, Moore C, Chater-Diehl E, Singh S, Rice C. Human COL5A1 polymorphisms and quadriceps muscle-tendon mechanical stiffness in vivo. Ahead of print: Exp Physiol; 2016.

Foster BP, Morse CI, Onambele GL, Williams AG. Human COL5A1 rs12722 gene polymorphism and tendon properties in vivo in an asymptomatic population. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114(7):1393–402.

Summers KM, Snodgrass SJ, Callister R. Predictors of calf cramping in rugby league. J Strength Cond Res . 2014;28(3):774–83.

Posthumus M, Schwellnus MP, Collins M. The COL5A1 gene: a novel marker of endurance running performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(4):584–9.

Bertuzzi R, Pasqua LA, Bueno S, Lima-Silva AE, Matsuda M, Marquezini M, et al. Is the COL5A1 rs12722 gene polymorphism associated with running economy? PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106581.

Pruna R, Artells R, Ribas J, Montoro B, Cos F, Muñoz C, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with non-contact soft tissue injuries in elite professional soccer players: influence on degree of injury and recovery time. BMC Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;14(1):1.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all athletes, their respective scientific support staff and the control participants for their time and willingness to participate in this research. We would like to thank Louis El Khoury for his technical assistance at the University of Northampton and Ben Davies, Craig Roberts, Bill Ribbans and Beth Vance for assistance in participant recruitment.

Funding

The present study was funded by Manchester Metropolitan University. Publication of this manuscript was supported by Manchester Metropolitan University.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Manchester Metropolitan University research data repository, http://researchdata.mmu.ac.uk/20/.

Follow the RugbyGene project at @RugbyGeneStudy.

Follow Shane Heffernan @Dr_Heff56.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Genomics Volume 18 Supplement 8, 2017: Proceedings of the 34th FIMS World Sports Medicine Congress. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcgenomics.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-18-supplement-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Listed alphabetically: MC, SD, RE, SH, LK, YP, AW and GW conceived and designed the study. MB, CC, MC, RE, SH, LK, SD, SR, GS, AW and GW contributed to data collection. SH and AW analysed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpretation of data, revised the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participant

Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committees of Manchester Metropolitan University, Glasgow University, University of Cape Town and University of Northampton and all experimental procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki (2003). All participates gave written informed consent to take part in the present study.

Consent for publication

All participates gave written informed consent for the results to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Heffernan, S.M., Kilduff, L.P., Erskine, R.M. et al. COL5A1 gene variants previously associated with reduced soft tissue injury risk are associated with elite athlete status in rugby. BMC Genomics 18 (Suppl 8), 820 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-4187-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-017-4187-3