Abstract

Background

Bacteria within the genus Photorhabdus maintain mutualistic symbioses with nematodes in complicated lifecycles that also involves insect pathogenic phases. Intriguingly, these bacteria are rich in biosynthetic gene clusters that produce compounds with diverse biological activities. As a basis to better understand the life cycles of Photorhabdus we sequenced the genomes of two recently discovered representative species and performed detailed genomic comparisons with five publically available genomes.

Results

Here we report the genomic details of two new reference Photorhabdus species. By then conducting genomic comparisons across the genus, we show that there are several highly conserved biosynthetic gene clusters. These clusters produce a range of bioactive small molecules that support the pathogenic phase of the integral relationship that Photorhabdus maintain with nematodes.

Conclusions

Photorhabdus contain several genetic loci that allow them to become specialist insect pathogens by efficiently evading insect immune responses and killing the insect host.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Members of the genus Photorhabdus include both insect and human pathogens. Despite only three distinct species described to date (P. luminescens, P. temperata and P. asymbiotica), significant sequence divergence within each species has led to the identification of several subspecies [1–7]. All three species maintain complex life cycles that include a nematode mutualistic symbiont as well as a pathogenic phase. During the symbiotic phase, the bacteria colonize nematodes of the genus Heterorhabditis during the infective juvenile (IJ) stage. The nematodes are generally free living in soil and seek out insects to infect so as to utilize the nutrients for growth and perpetuation of their progeny [8]. This is the dominant life cycle of the Photorhabdus however, occasional human infections by P. asymbiotica do occur [9]. During the infective stage, nematodes enter the insect and release the bacteria directly into the hemolymph where the bacteria also proliferate and eventually kill the insect. The insect cadaver provides a rich source of nutrients for both the nematode and the bacteria. Following proliferation of both, the bacteria re-colonize the nematode IJs before re-entering the soil in search of a new host [8].

Throughout this existence, the nematodes provide the bacteria with a means of transport while the bacteria supply a variety of secondary metabolites produced by biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Products of these BGCs are small molecules, frequently polyketides (PK), or non-ribosomal peptides (NRP) and can additionally include bacteriocins, siderophores and fatty acids among others. While there are common themes in their biosynthesis, each class of small molecule has a different mechanism of production and probably varying functions, with the majority of currently known metabolites reported as having some antimicrobial role [10–16]. Not all of these metabolites are required for symbiosis [17] so secondary metabolite biosynthesis alone - while important - does not explain the conservation of their corresponding genetic loci among closely related Photorhabdus or other entomopathogens of the genus Xenorhabdus [18].

The conservation of these general types of molecules led us to investigate whether there was a more generally conserved function. Through genome mining and using representative genomes from each species (and subspecies) of Photorhabdus, we compare seven different genomes in order to better understand the differences between the specific niche of each bacterium and the key analogous functions among the shared protein-coding DNA sequences (CDS).

Significant research has been conducted on Xenorhabdus species and their response to infection of insects. The role of some compounds produced by members of both genera has firmly been established as symbiotic factors [17, 19, 20] while others are predicted to be involved in this process. A role for a small number of secondary metabolites has been proposed in nematode development, however the majority of the BGCs appear to have little effect on this process (unpublished data). Following insect infection by nematodes, the bacteria are released into the insect hemolymph, quickly activating the cellular and humoral immune responses against the causative pathogens via one of two pathways, the Toll or immunodeficiency (IMD) pathways. The Toll pathway is activated in response to infection by Gram-positive bacteria and fungi using pattern-recognition receptors that respond to pathogen-associated molecular patterns [21–23]. On the other hand, Gram-negative pathogens activate the IMD pathway. This differential activation results in expression of a distinct set of genes for each in response to the type of infection occurring. However, subsets of overlapping sequences that are activated in both pathways have been identified in Drosophila and act synergistically in order to more efficiently deal with invading organisms [24, 25]. Alternatively, prophenoloxidase (proPO) pathways can be activated by exposure to lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycan, amphiphilic lipids or even damaged cells [26, 27]. ProPO is activated through cleavage by a serine protease resulting in active phenoloxidase (PO) that assists in pathogen isolation and lysis [28]. Several different serine protease inhibitors heavily regulate this system, as excess PO can be detrimental to the host [27, 29]. Some compounds from P. luminescens have recently been given defined roles in suppressing some parts of this insect immune response [30, 31].

One previous study has examined the similarities between P. luminescens and Yersinia enterocolitica in order to draw conclusions regarding key factors involved in insect pathogenesis [32]. In order to determine the conserved features of members of Photorhabdus and draw more specific conclusions with respect to the essential roles of proteins in the Photorhabdus lifecycle, we sequenced two novel isolates that, together with the already sequenced genomes, provide a broad geographical and genomic perspective of the genus. Using a comparative genomic approach, we highlight mechanisms that are conserved across the genus and predict possible functions of the products of the numerous BGCs and conserved signaling pathways.

Results

Genome composition of Photorhabdus spp. collected from Thailand

In order to establish a broad collection of Photorhabdus strains, we sequenced two additional isolates collected from Thailand [33]. However, Thanwisai et al. did note that the bacteria grouped into five distinct clades with Group 3 still lacking a reference strain. Sequencing of Photorhabdus PB45.5 and PB68.1 now provide reference sequences for Groups 3 and 5, respectively [33]. These Whole Genome Shotgun projects have been deposited at GenBank under the accession numbers LOIC00000000 and LOMY00000000, respectively.

Following sequencing and assembly (statistics available in Additional file 1), we performed an average nucleotide identity analysis on the genomes in order to determine the species. Photorhabdus PB68.1 was closely related to P. asymbiotica subsp. australis (ANI = 97.0 %) while Photorhabdus PB45.5 is most closely related to P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (ANI = 91.4 %) and may represent a novel subspecies. The genomes consist of 4,918,001 and 5,425,505 bp with GC contents of 42.0 and 42.7 % respectively. P. asymbiotica PB68.1 is predicted to contain 4600 CDS whilst Photorhabdus PB45.5 contains only 4353 CDS.

Together with P. luminescens TTO1 (NC_005126) [2], P. temperata subsp. khanii NC19 (NZ_AYSJ00000000) [4, 34], P. temperata subsp. temperata M1021 (NZ_AUXQ00000000) [3], P. temperata subsp. thracencis DSM 15199 (NZ_CP011104) [1] and P. asymbiotica ATCC 43949 (NC_012962) [6] we identified ortholog families across the seven strains. During ortholog identification, all protein singletons were removed from further analysis. This analysis suggests that the core Photorhabdus genome consists of a total of 2101 CDS, 520 of which are absent in E. coli K12 (Additional file 2). Using the KAAS server [35], KEGG orthology numbers were assigned to the fully assembled genomes (Additional file 3) and mapping to KEGG pathways was performed (Additional file 4). No obvious differences were apparent except for a much greater number of two-component systems present in P. luminescens TTO1 (96) compared to either P. asymbiotica ATCC 43949 (87) or P. temperata subsp. thracensis DSM 15199 (84).

Discussion

Biosynthetic gene clusters are numerous and diverse

The extensive core genome for the Photorhabdus suggests that many features of the lifestyle, regardless of the host, are conserved. One major drawback in trying to identify BGCs that are common across the genus is that the P. temperata NC19 and M1021 assemblies contain several BGCs that appear to be heavily fragmented. However, predicted reconstruction (see methods) of these BGC’s provides some insight into the presence or absence of clusters identified in the fully sequenced strains (Fig. 1, Additional file 5) and confirms the findings performed on the analysis of P. temperata NC19 by Hurst et al. [34]. A total of 75 BGCs were identified in the seven sequenced strains with several species specific BGCs. This number may however still be an over estimation of the true number of BGCs given that P. temperata subsp. khanii NC19 is one of the most heavily fragmented assemblies and contains 40 predicted clusters (some of which span whole contigs), while the average of the other members of the genus is only 21 (Table 1). It should be noted that these reconstructions may be fragmented due to rearrangements in the respective genomes as has been shown by the analysis between P. luminescens TTO1, P. temperata NC19 and P. asymbiotica ATCC 43949 previously [34]. Functional characterization of the BGCs by chemical analysis will be an important area of future research. Despite this, it is still interesting that there is so much apparent diversity with respect to the predicted products.

Map of highly conserved BGCs (present in at least 5 strains) in Photorhabdus spp. Following antiSMASH analysis, clusters were aligned using Mauve (v2.3.1) to identify homologous sequences. Domain architecture was checked using the conserved domain database from NCBI for each cluster to ensure consistency across the proposed families. Class of compound, names of identified compounds and domain structures are indicated. For all BGCs, see Additional file 5. Grey boxes represent the reported cluster, not identified by antiSMASH (see Methods)

P. luminescens TTO1 contains 23 predicted BGCs with several of the products already described, many of which have reported antimicrobial activity [17, 24, 36–44]. Ten of these BGCs correlate with a core set of secondary metabolites that exists within the genus (Fig. 1). Some of these natural products are involved in development of the nematode while strains completely deficient in secondary metabolite production fail to support nematode development (Tobias, Heinrich, Eresmann, Neubacher and Bode, unpublished results). Structural similarities, compound class comparisons and proven structure-function relationships suggests that many of these remaining products have one of two main functions; cell-cell signaling or immune evasion. We suggest that the reported antimicrobial activities of some natural products may merely be a coincidental side effect of the actual compound function similar to some antibiotics [45]. Another possibility is that the same compound might have different functions in different biological contexts as exemplified by isopropylstilbene from Photorhabdus acting as an antibiotic against fungi and bacteria [46], shows cytotoxic activity against insect and other eukaryotic cells [47] while also required for proper nematode development [19].

Several regions in the genomes appear to contain multiple adjacent BGCs (clusters 25, 33, 41 and 43), deduced from the presence of multiple terminal thioesterase (TE) domains that usually define the endpoint of a NRPS pathway, with three of the four present in P. temperata strains (Additional file 5). This may indicate a complementary function of the products of the BGC as seen for pristinamycin, a synergistically acting two-component antibiotic [48]. Identifying the products and functions of those BGCs that are species-specific (Additional files 5 and 6) may provide insights into the different niches occupied by these bacteria.

Immune evasion mechanisms

Many of the remaining compounds have yet to have a definitive function assigned to them. However, the extensive research performed in Xenorhabdus and similar compounds from other species, suggests that many have immune evasion functions. There is the distinct possibility that Photorhabdus BGCs are essential for supporting the nematode development, perhaps helping to distinguish them from closely related species that also infect insects, without nematodal assistance, such as Serratia or Yersinia [49]. While this may be true for some compounds, we suggest that the mutualistic symbiosis has been made more successful by acquisition of new BGCs by the bacteria enabling them to more efficiently overcome the host defense and consequently, killing the host more efficiently so that both bacteria and nematode benefit.

Rhabduscin is a prime example of an essential immune defensive compound produced by the IsnA and IsnB proteins, which encode an isocyanide synthase and a α-ketoglutarate dependent oxygenase respectively, together producing a potent phenoloxidase inhibitor [30, 50]. Examination of the genomes reveals that only isnA is present in all sequences whilst isnB is missing in P. temperata M1021 (cluster 11, Fig. 1). This suggests that instead of rhabduscin, there would be an accumulation of a reportedly unstable isocyanide-containing intermediate [50] in this strain or an alternative and yet unknown transformation of the unstable intermediate. Despite this, five species also contain the rhabdopeptide cluster (involved in mevalagmapeptide production [42]) that may be a redundant mechanism for PO inhibition (Fig. 2). Suppression of the phenoloxidase activity by rhabdopeptides has recently been described (Cai and Bode, unpublished results). This suppression method is reported to inhibit the serine protease cascade that leads to proPO cleavage. A mechanism of flexible synthesis by the rhabdopeptide system that occurs in a protein concentration dependent manner that results in differing lengths of ensuing products has also recently been uncovered (Cai, Nowak, Wesche, Bischoff, Kaiser, Fürst and Bode, submitted). This raises the possibility of a way by which the bacteria are able to either infect and suppress immune responses in a broad range of insects and efficiently evade the relevant immune systems or to address multiple targets in a single cell resulting in synergistic activity comparable to a combination therapy used in human treatments.

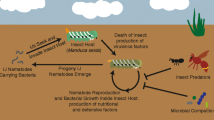

Schematic summary of the intricate tripartite lifecycle of Photorhabdus highlighting the produced specialized metabolites and predicted functions (indicated by a ‘?’ where unproven associations exist). Nematodes infect insects and release the bacteria inside the hemolymph before undergoing several rounds of development while the insect is killed. The bacteria release several compounds (dashed arrows) that variously affect the insect’s immune response. DAR = dialkylresorcinol, PPY = photopyrone

Siderophores are often essential in causing virulence in a range of bacteria (recently reviewed in [51–53]). One conserved cluster in Photorhabdus is predicted to produce a myxochelin-like siderophore (cluster 5, Fig. 1). Myxochelins have been shown to target and suppress the activity of 5-lipooxygenase [54], a key enzyme in the insect innate immune response (reviewed in [55]). Additionally, P. luminescens contains a further cluster with predicted siderophore function, a hydroxymate-like siderophore (cluster 74). Hydroxymate siderophores are potent histone deacetylase inhibitors. Histone deacetylases are involved in transcriptional reprogramming during wounding and infection and have been shown to repress antimicrobial peptide (AMP) production in Galleria mellonella, a common insect model for Photorhabdus virulence [56]. In addition to these specific roles, we cannot rule out the possibility that these siderophores also play a more general iron-scavenging role within the insect or nematode.

Phospholipase-2 (PLA-2) is a part of the eicosanoid biosynthesis pathway that is activated in response to recognition of pathogens by the insect. The eicosanoids are essential in mediating activation of phagocytosis and proPO production in the insect hemolymph [57]. Seo et al. (2012) have recently found that several Photorhabdus species are capable of inhibiting this by production of benzylideneacetone thereby preventing the recruitment of hemocytes and activation of phagocytosis [37, 58]. Benzylideneacetone is likely derived from the IPS biosynthetic pathway (extension of the phenylalanine derived cinnamoyl-CoA), which is a BGC conserved in all strains (cluster 9, Fig. 1) [38]. A further mechanism of insect immune suppression is via proteasome inhibition. Recently, glidobactin A and its iso-branched acyl derivative cepafungin, products of an NRPS-PKS hybrid gene cluster that is highly conserved (Fig. 1), were reported to be produced by Photorhabdus and are potent proteasome inhibitors [39, 59]. An overview of possible immune evasive and suppression mechanisms as they relate to natural products in P. luminescens is provided in Fig. 2.

Two-component signal transduction systems

Six two-component systems (TCS) were conserved in all Photorhabdus species as well as E. coli, with a further system present only in all Photorhabdus strains. Among the conserved two-component systems is the well described CpxRA TCS, which is involved in a range of cellular processes from synthesis and translocation of cell membrane proteins [60–63] to resistance to AMPs [64] and various other virulence phenotypes [65–67]. BaeRS was also implicated in regulating multidrug resistance in E. coli [68] while TctED is involved in tricarboxylic acid transport [69] and UhpAB in involved in sugar transport pathways, responding to extracellular glucose [70]. The OmpR/EnvZ TCS is also well described in E. coli and is central in regulating the Omp locus in response to external osmolarity alterations [71, 72]. The final TCS is the PhoPQ system, which is post-translationally controlled by sRNAs [73] and responds to magnesium concentrations or AMPs in the environment [74]. However, the single TCS unique to Photorhabdus is the AstSR that was previously identified as being important in Photorhabdus phase switching [75] and identified as a likely component involved in insect infection [32].

Cell-cell communication

We have recently reported two new classes of bacterial signaling molecules in Photorhabdus, namely the photopyrones (PPY) and dialkylresorcinols (DAR) [36, 40]. The DAR and PPY signaling pathways represent new methods of cell-cell communication and were discovered through the analysis of LuxR orphans (reviewed in [76]). While the DAR locus was identified in all strains (a part of the IPS biosynthesis shown in cluster 9, Fig. 1), the PPYs were only found in P. luminescens TTO1 and P. temperata subsp. thracencis suggesting a far less important role for PPYs (cluster 72, Additional file 5). Additionally, there are several other LuxR orphans in these bacteria with unidentified signals. One possibility is that some of the unknown clusters produce compounds can be sensed by these receptors. Another possibility that has been raised is the promiscuous activation of these receptors through compounds produced by either the nematode or insect prey, representing a form of cross-kingdom communication [41].

Only three additionally conserved regulatory proteins are present in all Photorhabdus examined. Two of these candidates are from the class of aforementioned LuxR orphans while the remaining is the HpaA regulator involved in the degradation of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, which while absent in E. coli K12, is present in several other E. coli strains [77, 78]. It is also important to note that 872 (409 absent in E. coli K12) hypothetical proteins are additionally conserved with several potentially having undefined regulatory roles (Additional file 2).

Other conserved virulence factors

Other predicted virulence factors conserved across the genus include a number of different protein toxins, a fli locus for flagellar assembly, a secretion system as well as various other insect associated proteins. PrtA, a protein known to be involved in insect colonization is present in all Photorhabdus strains [79]. Additionally, the genus contains a particularly large repertoire of protein toxins. The insecticidal toxin complex (Tc) proteins are over-represented in the total number. The Tc toxins consist of four sub-types, predicted to have different host targets [80], each of which is represented in the P. luminescens genomes. In total there are 16 annotated Tc protein families, all of which are present in both P. luminescens strains while the P. temperata strains have between eight and 11 proteins and the P. asymbiotica strains have only eight. Additionally, the repeats-in-toxin (Rtx)-like toxin are cytotoxins conserved in many Gram-negative pathogens [81] and similarly in all Photorhabdus. The mcf (makes caterpillars floppy) toxin now has an established role in insect pathogenicity in P. luminescens TTO1 with its presence enough to allow E. coli to kill insects [82–84]. Interestingly, this protein is present in all strains except for P. temperata M1021. However, the absence of this and a disproportionate number of other CDS that are present in all other Photorhabdus may just be indicative of the highly fragmented nature of this assembly in comparison to the others. Re-sequencing of this strain using long-read technology will provide more conclusive answers.

Photorhabdus contains only a single Type III secretion system (T3SS) that is absent in E. coli K12. Most strains have maintained the entire system while P. temperata M1021 has lost three genes (sctC, sctV and sctP), while P. asymbiotica and P. temperata subsp. thracencis are missing sctE and sctP, respectively. Of these missing homologs, only SctC and SctV are described as core proteins in this T3SS [85, 86] suggesting that P. temperata M1021 contains a non-functional T3SS. Additionally, this strain is the only strain lacking a full flagellar assembly locus (Additional file 7). Since there is significant evidence that this T3SS has a role in exporting insecticidal toxins [87], it is possible that this is merely an assembly artifact or that these bacteria instead kill insects via a different mechanism than that predicted by other Photorhabdus.

In terms of other host-associated proteins, each strain contains at least one predicted bacteriocin (Table 1), presumably to protect the insect cadaver from scavenging competitors. A total of five different bacteriocins were identified of which only one homolog is conserved in all P. luminescens and P. temperata strains but absent from both P. asymbiotica isolates (cluster 10, Fig. 1). Elucidation of the mechanism of this bacteriocin or a specific target may provide some insight into the competitors encountered by the respective species.

Species-specific orthologs

Each of the individual species contained several coding sequences that were unique with the majority, unsurprisingly, consisting of hypothetical proteins (Table 2). However, what is interesting is that each Photorhabdus species appears to have a unique repertoire of regulatory proteins when compared to one another, presumably responsible for activating niche specific pathways. Within the P. luminescens, BLASTp searches of the non-redundant protein database show that of the regulators, one is a LysR-like regulator, one has no known domains while the four remaining are part of the XRE (xenobiotic response element) family of transcriptional regulators. The unknown regulator (plu0963/Phpb_03473) is located within the unique Tc locus indicating that it is probably a regulator for these toxins. Xenobiotics are compounds not normally found in the cell and are often detrimental. If the XRE-like regulators are in fact responding to xenobiotics and subsequently degrading them, then the elucidation of both the signal and the downstream response may provide some clear indications as to the environment in which these species are living. The P. asymbiotica isolates contain several additional secretion system proteins, effector molecules and what was annotated as a predicted macrophage resistance protein. This resistance protein may be a key factor in the reported ability of P. asymbiotica to survive and replicate within macrophages [88]. Two unique regulators from P. asymbiotica are the SlyA and CadC regulators (Additional files 8, 9, and 10), which have both been implicated in virulence-associated phenotypes. SlyA was found to play a role in persistence within the host cell in Enterococcus faecalis [89] while CadC is responsible for activating the cadBA locus in response to acid stress or lysine signals [90]. Perhaps more interesting however, is the absence of cadC in the other species. CadC is a positive regulator of the cad locus while negatively regulating the arginine-dependent acid response system [91]. The absence of cadC is a key feature of both Shigella and enteroinvasive E. coli. This absence in the other strains could indicate a form of adaptive evolution as seen in the other pathogenic enterobacteria that allows these bacteria to respond more appropriately to low pH environments.

Conclusions

The identification of conserved protein families across Photorhabdus has helped to shed light on possible pathways essential to the intricate lifecycle of the genus. Given the roles assigned to known compounds as well as those that have yet to be confirmed but share similarities with known compounds, we suggest that many of these BGCs have been acquired as virulence factors early during speciation of the Photorhabdus, with one of two main functions; cell-cell communication, or modulating the insect immune response. The common belief is that many of these specialized metabolites are essential for differing antimicrobial roles. However, given the relatively low biological activity of these compounds we propose that, although they appear to have these activities, this is merely a side effect of their true function. Deconstructing the novel regulatory pathways will go a long way towards understanding each individual environment. Furthermore, the elucidation of the functions of products of the BGCs as well as whole genome comparisons to the Xenorhabdus species will be important areas of future research to fully understand the ecological niche occupied by these bacteria.

Methods

Strains and culture conditions

All Photorhabdus strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (pH 7.0) at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. All strains used in this study are listed in Table 3.

DNA methods

DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Photorhabdus PB68.1 and PB45.5 were sequenced at Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany) using an Illumina HiSeq2500 instrument with 150 bp paired end reads.

Genome assembly and annotation

Raw reads were processed to trim the attached adapters and low-quality bases from both ends using Trimmomatic (v 0.32) [84] with the parameters “ILLUMINACLIP:<path to adapter sequences>:2:30:10 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15”. Further, an in-house perl script (Additional file 11) was used to discard read pairs having an average base quality less than 30, having Ns in the sequence or less than 90 bases long. After cleaning reads using the above criteria, cleaned read pairs with a minimum 90 bases in both forward and reverse reads were used for assembly. De novo assemblies were carried out using Velvet (v 1.2.10) [85]. To obtain optimal assemblies for both genomes, 12 assemblies for each genome were generated using odd k-mer lengths between 71 and 89, with default parameters and “-exp_cov auto”. Optimal assembly was chosen on the basis of assembled genome size, longest scaffold size, number of scaffolds, N50, N90, percentage of N in the assembly. For both genomes, the optimal assembly was obtained with a k-mer length of 89. Scaffolds longer than 300 bases were considered for gene prediction and further analyses. Following assembly, all genomes were annotated using prokka (v1.12) with default settings and --addgenes, −-compliant and --gram neg options activated [92]. Protein orthologs among the seven Photorhabdus strains and E. coli K12 were determined using proteinortho5 [93]. ANI calculations were performed using EzGenome (available at http://www.ezbiocloud.net/ezgenome). Assigning of KEGG orthology numbers and mapping to KEGG pathways was performed using the KEGG automatic annotation server [35]. QUAST was used to assess assembly quality [94].

Secondary metabolite cluster identification

BGCs were identified using antiSMASH v3.0 [95] together with the optional ClusterFinder algorithm using the annotated genomes as input. DNA sequences of clusters identified by antiSMASH were used in Mauve alignments to identify homologous regions to gene clusters from the already available, fully assembled genomes, enabling in silico reconstruction of some BGCs that were heavily fragmented. Presence of isnA and isnB, genes known to produce rhabduscin, an important immunomodulatory compound in related species, was performed manually using BLASTp (v2.2.29) as a part of the BLAST+ suite [96] with the IsnA and IsnB sequences from Xenorhabdus nematophila [30] used as input.

Abbreviations

AMP, antimicrobial peptide; ANI, average nucleotide identity; BGC, biosynthetic gene cluster; DAR, dialkylresorcinol; FAS, fatty acid synthase; IJ, infective juvenile; IMD, immunodeficiency; IPS, isopropylstilbene; NRP, non-ribosomal peptide; NRPS, non-ribosomal peptide synthetase; PK, polyketide; PKS, polyketide synthase; PLA-2, phospholipase-A2; PO, phenoloxidase; PPY, photopyrone; proPO, pro-phenoloxidase; T3SS, type III secretion system; Tc, toxin complex; TCS, two-component system

References

Kwak Y, Shin JH. Complete genome sequence of Photorhabdus temperata subsp. thracensis 39-8, an entomopathogenic bacterium for the improved commercial bioinsecticide. J Biotechnol. 2015;214:115–6.

Duchaud E, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Givaudan A, Taourit S, Bocs S, Boursaux-Eude C, Chandler M, Charles JF, et al. The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1307–13.

Park GS, Khan AR, Hong SJ, Jang EK, Ullah I, Jung BK, Choi J, Yoo NK, Park KJ, Shin JH. Draft Genome Sequence of Entomopathogenic Bacterium Photorhabdus temperata Strain M1021, Isolated from Nematodes. Genome Announc. 2013;1(5);e00747-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00747-13.

Tailliez P, Laroui C, Ginibre N, Paule A, Pages S, Boemare N. Phylogeny of photorhabdus and xenorhabdus based on universally conserved protein-coding sequences and implications for the taxonomy of these two genera. Proposal of new taxa: X. Vietnamensis sp. nov., P. Luminescens subsp. Caribbeanensis subsp. nov., P. Luminescens subsp. Hainanensis subsp. nov., P. Temperata subsp. Khanii subsp. nov., P. Temperata subsp. Tasmaniensis subsp. nov., and the reclassification of P. Luminescens subsp. Thracensis as P. Temperata subsp. Thracensis comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:1921–37.

Hazir S, Stackebrandt E, Lang E, Schumann P, Ehlers RU, Keskin N. Two new subspecies of photorhabdus luminescens, isolated from Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (nematoda: heterorhabditidae): photorhabdus luminescens subsp. Kayaii subsp. nov. And photorhabdus luminescens subsp. Thracensis subsp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2004;27:36–42.

Wilkinson P, Waterfield NR, Crossman L, Corton C, Sanchez-Contreras M, Vlisidou I, Barron A, Bignell A, Clark L, Ormond D, et al. Comparative genomics of the emerging human pathogen Photorhabdus asymbiotica with the insect pathogen Photorhabdus luminescens. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:302.

Fischer-Le Saux M, Viallard V, Brunel B, Normand P, Boemare NE. Polyphasic classification of the genus photorhabdus and proposal of new taxa: P. Luminescens subsp. Luminescens subsp. nov., P. Luminescens subsp. Akhurstii subsp. nov., P. Luminescens subsp. Laumondii subsp. nov., P. Temperata sp. nov., P. Temperata subsp. Temperata subsp. nov. And P. Asymbiotica sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49(4):1645–56.

Han R, Ehlers RU. Pathogenicity, development, and reproduction of Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and Steinernema carpocapsae under axenic in vivo conditions. J Invertebr Pathol. 2000;75:55–8.

Gerrard JG, Vohra R, Nimmo GR. Identification of Photorhabdus asymbiotica in cases of human infection. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:540–1.

Kronenwerth M, Bozhuyuk KA, Kahnt AS, Steinhilber D, Gaudriault S, Kaiser M, Bode HB. Characterisation of taxlllaids A-G; natural products from Xenorhabdus indica. Chemistry. 2014;20:17478–87.

Lang G, Kalvelage T, Peters A, Wiese J, Imhoff JF. Linear and cyclic peptides from the entomopathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1074–7.

Oka M, Numata K, Nishiyama Y, Kamei H, Konishi M, Oki T, Kawaguchi H. Chemical modification of the antitumor antibiotic glidobactin. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1988;41:1812–22.

Oka M, Ohkuma H, Kamei H, Konishi M, Oki T, Kawaguchi H. Glidobactins D, E, F, G and H; minor components of the antitumor antibiotic glidobactin. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1988;41:1906–9.

Schimming O, Fleischhacker F, Nollmann FI, Bode HB. Yeast homologous recombination cloning leading to the novel peptides ambactin and xenolindicin. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1290–4.

Velasco A, Acebo P, Gomez A, Schleissner C, Rodriguez P, Aparicio T, Conde S, Munoz R, de la Calle F, Garcia JL, Sanchez-Puelles JM. Molecular characterization of the safracin biosynthetic pathway from Pseudomonas fluorescens A2-2: designing new cytotoxic compounds. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:144–54.

Zhou Q, Dowling A, Heide H, Wohnert J, Brandt U, Baum J, Ffrench-Constant R, Bode HB. Xentrivalpeptides A-Q: depsipeptide diversification in Xenorhabdus. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:1717–22.

Brachmann AO, Joyce SA, Jenke-Kodama H, Schwar G, Clarke DJ, Bode HB. A type II polyketide synthase is responsible for anthraquinone biosynthesis in Photorhabdus luminescens. Chembiochem. 2007;8:1721–8.

Goodrich-Blair H, Clarke DJ. Mutualism and pathogenesis in Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus: two roads to the same destination. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:260–8.

Joyce SA, Brachmann AO, Glazer I, Lango L, Schwar G, Clarke DJ, Bode HB. Bacterial biosynthesis of a multipotent stilbene. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:1942–5.

Joyce SA, Clarke DJ. A hexA homologue from Photorhabdus regulates pathogenicity, symbiosis and phenotypic variation. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1445–57.

Bischoff V, Vignal C, Boneca IG, Michel T, Hoffmann JA, Royet J. Function of the drosophila pattern-recognition receptor PGRP-SD in the detection of Gram-positive bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1175–80.

Filipe SR, Tomasz A, Ligoxygakis P. Requirements of peptidoglycan structure that allow detection by the Drosophila Toll pathway. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:327–33.

Michel T, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA, Royet J. Drosophila toll is activated by gram-positive bacteria through a circulating peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature. 2001;414:756–9.

De Gregorio E, Spellman PT, Tzou P, Rubin GM, Lemaitre B. The toll and Imd pathways are the major regulators of the immune response in drosophila. EMBO J. 2002;21:2568–79.

Tanji T, Hu X, Weber AN, Ip YT. Toll and IMD pathways synergistically activate an innate immune response in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4578–88.

Sugumaran M, Nellaiappan K. Lysolecithin--a potent activator of prophenoloxidase from the hemolymph of the lobster, Homarus americanas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:1371–6.

Cerenius L, Soderhall K. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:116–26.

Nappi AJ, Vass E. Melanogenesis and the generation of cytotoxic molecules during insect cellular immune reactions. Pigment Cell Res. 1993;6:117–26.

Nappi AJ, Christensen BM. Melanogenesis and associated cytotoxic reactions: applications to insect innate immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:443–59.

Crawford JM, Portmann C, Zhang X, Roeffaers MB, Clardy J. Small molecule perimeter defense in entomopathogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10821–6.

Felfoldi G, Marokhazi J, Kepiro M, Venekei I. Identification of natural target proteins indicates functions of a serralysin-type metalloprotease, PrtA, in anti-immune mechanisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:3120–6.

Heermann R, Fuchs TM. Comparative analysis of the photorhabdus luminescens and the Yersinia enterocolitica genomes: uncovering candidate genes involved in insect pathogenicity. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:40.

Thanwisai A, Tandhavanant S, Saiprom N, Waterfield NR, Ke Long P, Bode HB, Peacock SJ, Chantratita N. Diversity of xenorhabdus and photorhabdus spp. And their symbiotic entomopathogenic nematodes from Thailand. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43835.

Hurst S, Rowedder H, Michaels B, Bullock H, Jackobeck R, Abebe-Akele F, Durakovic U, Gately J, Janicki E, Tisa LS. Elucidation of the photorhabdus temperata genome and generation of a transposon mutant library to identify motility mutants altered in pathogenesis. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:2201–16.

Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W182–185.

Brameyer S, Kresovic D, Bode HB, Heermann R. Dialkylresorcinols as bacterial signaling molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:572–7.

Seo S, Lee S, Hong Y, Kim Y. Phospholipase A2 inhibitors synthesized by two entomopathogenic bacteria, Xenorhabdus nematophila and Photorhabdus temperata subsp. temperata. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3816–23.

Fuchs SW, Bozhuyuk KA, Kresovic D, Grundmann F, Dill V, Brachmann AO, Waterfield NR, Bode HB. Formation of 1,3-cyclohexanediones and resorcinols catalyzed by a widely occurring ketosynthase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:4108–12.

Dudnik A, Bigler L, Dudler R. Heterologous expression of a Photorhabdus luminescens syrbactin-like gene cluster results in production of the potent proteasome inhibitor glidobactin A. Microbiol Res. 2013;168:73–6.

Brachmann AO, Brameyer S, Kresovic D, Hitkova I, Kopp Y, Manske C, Schubert K, Bode HB, Heermann R. Pyrones as bacterial signaling molecules. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:573–8.

Bode HB, Brachmann AO, Jadhav KB, Seyfarth L, Dauth C, Fuchs SW, Kaiser M, Waterfield NR, Sack H, Heinemann SH, Arndt HD. Structure elucidation and activity of kolossin a, the D-/L-pentadecapeptide product of a giant nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:10352–5.

Bode E, Brachmann AO, Kegler C, Simsek R, Dauth C, Zhou Q, Kaiser M, Klemmt P, Bode HB. Simple “on-demand” production of bioactive natural products. Chembiochem. 2015;16:1115–9.

Nollmann FI, Dauth C, Mulley G, Kegler C, Kaiser M, Waterfield NR, Bode HB. Insect-Specific Production of New GameXPeptides in Photorhabdus luminescens TTO1, Widespread Natural Products in Entomopathogenic Bacteria. Chembiochem. 2015;16;205-8. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402603. Epub 2014 Nov 25

Brachmann AO, Kirchner F, Kegler C, Kinski SC, Schmitt I, Bode HB. Triggering the production of the cryptic blue pigment indigoidine from Photorhabdus luminescens. J Biotechnol. 2012;157:96–9.

Yim G, Wang HH, Davies J. Antibiotics as signalling molecules. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362:1195–200.

Li J, Chen G, Wu H, Webster JM. Identification of two pigments and a hydroxystilbene antibiotic from Photorhabdus luminescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4329–33.

Buscato E, Buttner D, Bruggerhoff A, Klingler FM, Weber J, Scholz B, Zivkovic A, Marschalek R, Stark H, Steinhilber D, et al. From a multipotent stilbene to soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors with antiproliferative properties. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:919–23.

Mast Y, Weber T, Golz M, Ort-Winklbauer R, Gondran A, Wohlleben W, Schinko E. Characterization of the ‘pristinamycin supercluster’ of Streptomyces pristinaespiralis. Microb Biotechnol. 2011;4:192–206.

Castagnola A, Stock SP. Common virulence factors and tissue targets of entomopathogenic bacteria for biological control of lepidopteran pests. Insects. 2014;5:139–66.

Brady SF, Clardy J. Cloning and heterologous expression of isocyanide biosynthetic genes from environmental DNA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:7063–5.

Saha R, Saha N, Donofrio RS, Bestervelt LL. Microbial siderophores: a mini review. J Basic Microbiol. 2013;53:303–17.

Koh EI, Henderson JP. Microbial copper-binding siderophores at the host-pathogen interface. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:18967–74.

Sheldon JR, Heinrichs DE. Recent developments in understanding the iron acquisition strategies of gram positive pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015;39:592–630.

Schieferdecker S, Konig S, Koeberle A, Dahse HM, Werz O, Nett M. Myxochelins target human 5-lipoxygenase. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:335–8.

González-Santoyo I, Córdoba-Aguilar A. Phenoloxidase: a key component of the insect immune system. Entomol Exp Appl. 2012;142:1–16.

Mukherjee K, Fischer R, Vilcinskas A. Histone acetylation mediates epigenetic regulation of transcriptional reprogramming in insects during metamorphosis, wounding and infection. Front Zool. 2012;9:25.

Downer RG, Moore SJ WLD-J, Mandato CA. The effects of eicosanoid biosynthesis inhibitors on prophenoloxidase activation, phagocytosis and cell spreading in galleria mellonella. J Insect Physiol. 1997;43:1–8.

Kim Y, Ji D, Cho S, Park Y. Two groups of entomopathogenic bacteria, Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, share an inhibitory action against phospholipase A2 to induce host immunodepression. J Invertebr Pathol. 2005;89:258–64.

Stein ML, Beck P, Kaiser M, Dudler R, Becker CF, Groll M. One-shot NMR analysis of microbial secretions identifies highly potent proteasome inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18367–71.

Danese PN, Silhavy TJ. The sigma(E) and the Cpx signal transduction systems control the synthesis of periplasmic protein-folding enzymes in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1183–93.

Danese PN, Silhavy TJ. CpxP, a stress-combative member of the Cpx regulon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:831–9.

Raivio TL, Popkin DL, Silhavy TJ. The Cpx envelope stress response is controlled by amplification and feedback inhibition. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5263–72.

Raivio TL, Silhavy TJ. The sigmaE and Cpx regulatory pathways: overlapping but distinct envelope stress responses. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:159–65.

Weatherspoon-Griffin N, Yang D, Kong W, Hua Z, Shi Y. The CpxR/CpxA two-component regulatory system up-regulates the multidrug resistance cascade to facilitate Escherichia coli resistance to a model antimicrobial peptide. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:32571–82.

Nevesinjac AZ, Raivio TL. The Cpx envelope stress response affects expression of the type IV bundle-forming pili of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:672–86.

Ma Q, Wood TK. OmpA influences Escherichia coli biofilm formation by repressing cellulose production through the CpxRA two-component system. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2735–46.

De Wulf P, Kwon O, Lin EC. The CpxRA signal transduction system of Escherichia coli: growth-related autoactivation and control of unanticipated target operons. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6772–8.

Nagakubo S, Nishino K, Hirata T, Yamaguchi A. The putative response regulator BaeR stimulates multidrug resistance of Escherichia coli via a novel multidrug exporter system, MdtABC. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4161–7.

Widenhorn KA, Somers JM, Kay WW. Expression of the divergent tricarboxylate transport operon (tctI) of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3223–7.

Weston LA, Kadner RJ. Role of uhp genes in expression of the Escherichia coli sugar-phosphate transport system. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3375–83.

Egger LA, Park H, Inouye M. Signal transduction via the histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelay. Genes Cells. 1997;2:167–84.

Forst SA, Roberts DL. Signal transduction by the EnvZ-OmpR phosphotransfer system in bacteria. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:363–73.

Coornaert A, Chiaruttini C, Springer M, Guillier M. Post-transcriptional control of the Escherichia coli PhoQ-PhoP two-component system by multiple sRNAs involves a novel pairing region of GcvB. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003156.

Zwir I, Shin D, Kato A, Nishino K, Latifi T, Solomon F, Hare JM, Huang H, Groisman EA. Dissecting the PhoP regulatory network of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2862–7.

Derzelle S, Ngo S, Turlin E, Duchaud E, Namane A, Kunst F, Danchin A, Bertin P, Charles JF. AstR-AstS, a new two-component signal transduction system, mediates swarming, adaptation to stationary phase and phenotypic variation in Photorhabdus luminescens. Microbiology. 2004;150:897–910.

Brameyer S, Kresovic D, Bode HB, Heermann R. LuxR solos in Photorhabdus species. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:166.

Burlingame R, Chapman PJ. Catabolism of phenylpropionic acid and its 3-hydroxy derivative by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:113–21.

Prieto MA, Diaz E, Garcia JL. Molecular characterization of the 4-hydroxyphenylacetate catabolic pathway of Escherichia coli W: engineering a mobile aromatic degradative cluster. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:111–20.

Caldas C, Cherqui A, Pereira A, Simoes N. Purification and characterization of an extracellular protease from Xenorhabdus nematophila involved in insect immunosuppression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1297–304.

ffrench-Constant R, Waterfield N, Daborn P, Joyce S, Bennett H, Au C, Dowling A, Boundy S, Reynolds S, Clarke D. Photorhabdus: towards a functional genomic analysis of a symbiont and pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;26:433–56.

Lally ET, Hill RB, Kieba IR, Korostoff J. The interaction between RTX toxins and target cells. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:356–61.

Daborn PJ, Waterfield N, Silva CP, Au CP, Sharma S, Ffrench-Constant RH. A single Photorhabdus gene, makes caterpillars floppy (mcf), allows Escherichia coli to persist within and kill insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10742–7.

Daborn PJ, Waterfield N, Blight MA, Ffrench-Constant RH. Measuring virulence factor expression by the pathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens in culture and during insect infection. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5834–9.

Munch A, Stingl L, Jung K, Heermann R. Photorhabdus luminescens genes induced upon insect infection. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:229.

Cornelis GR. The type III secretion injectisome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:811–25.

Kosarewicz A, Konigsmaier L, Marlovits TC. The blueprint of the type-3 injectisome. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:1140–54.

Gendlina I, Held KG, Bartra SS, Gallis BM, Doneanu CE, Goodlett DR, Plano GV, Collins CM. Identification and type III-dependent secretion of the Yersinia pestis insecticidal-like proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1214–27.

Costa SC, Girard PA, Brehelin M, Zumbihl R. The emerging human pathogen Photorhabdus asymbiotica is a facultative intracellular bacterium and induces apoptosis of macrophage-like cells. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1022–30.

Michaux C, Sanguinetti M, Reffuveille F, Auffray Y, Posteraro B, Gilmore MS, Hartke A, Giard JC. SlyA is a transcriptional regulator involved in the virulence of Enterococcus faecalis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2638–45.

Lee YH, Kim JH, Bang IS, Park YK. The membrane-bound transcriptional regulator CadC is activated by proteolytic cleavage in response to acid stress. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5120–6.

Casalino M, Prosseda G, Barbagallo M, Iacobino A, Ceccarini P, Latella MC, Nicoletti M, Colonna B. Interference of the CadC regulator in the arginine-dependent acid resistance system of Shigella and enteroinvasive E. coli. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:289–95.

Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–9.

Lechner M, Findeiss S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:124.

Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–5.

Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Muller R, Wohlleben W, et al. antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W237–243.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinf. 2009;10:421.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Research in the Bode Laboratory is supported by European research starting grant under grant agreement no. 311477. A Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation supports NJT. Research in the Thines and Bode labs are supported by the LOEWE funding initiative of the Government of Hessen in the framework of IPF and the Thines lab is also supported by BiK-F.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Genbank repository, under the accession numbers LOIC00000000 (Photorhabdus PB45.5) and LOMY00000000 (Photorhabdus PB68.1).

Authors’ contributions

NJT extracted the DNA. BM, DKG, RS and MT designed and performed the genome assemblies. NJT and TS participated in genome annotation. NJT analysed the data. NJT and HBB conceived of the study. NJT, TS and HBB helped to design the experiment. NJT and HBB drafted the manuscript. MT, TS and HBB provided computational infrastructure. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Genome assembly statistics. (DOCX 40 kb)

Additional file 2:

All protein ortholog families. (XLSX 394 kb)

Additional file 3:

KO numbers for fully assembled genomes as assigned by the KAAS server. (XLSX 262 kb)

Additional file 4:

KEGG pathway analysis. Numbers indicate number of CDS with matching KO numbers in each pathway. (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 5:

Complete list of BGCs identified in seven strains of Photorhabdus. (DOCX 1138 kb)

Additional file 6:

Unique BGC in each species as shown in Additional file 5. (DOCX 34 kb)

Additional file 7:

Coding sequences mentioned in the text and their respective locus tags. (XLSX 47 kb)

Additional file 8:

P. asymbiotica specific coding sequences. (XLSX 20 kb)

Additional file 9:

P. luminescens specific coding sequences. (XLSX 16 kb)

Additional file 10:

P. temperata specific coding sequences. (XLSX 47 kb)

Additional file 11:

Perl code for filtering read pairs. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tobias, N.J., Mishra, B., Gupta, D.K. et al. Genome comparisons provide insights into the role of secondary metabolites in the pathogenic phase of the Photorhabdus life cycle. BMC Genomics 17, 537 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2862-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2862-4