Abstract

Background

Abnormal activation of human nuclear hormone receptors disrupts endocrine systems and thereby affects human health. There have been machine learning-based models to predict androgen receptor agonist activity. However, the models were constructed based on limited numerical features such as molecular descriptors and fingerprints.

Result

In this study, instead of the numerical features, 2-D chemical structure images of compounds were used to build an androgen receptor toxicity prediction model. The images may provide unknown features that were not represented by conventional numerical features. As a result, the new strategy resulted in a construction of highly accurate prediction model: Mathews correlation coefficient (MCC) of 0.688, positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.933, sensitivity of 0.519, specificity of 0.998, and overall accuracy of 0.981 in 10-fold cross-validation. Validation on a test dataset showed MCC of 0.370, sensitivity of 0.211, specificity of 0.991, PPV of 0.882, and overall accuracy of 0.801. Our chemical image-based prediction model outperforms conventional models based on numerical features.

Conclusion

Our constructed prediction model successfully classified molecular images into androgen receptor agonists or inactive compounds. The result indicates that 2-D molecular mimetic diagram would be used as another feature to construct molecular activity prediction models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Androgen receptor (AR) is one of nuclear receptors playing an important role in expressing male phenotype. AR is activated by steroid hormones such as testosterone and 5α-DHT [1]. Although AR-induced cellular functions are vital for early development and physiological regulations [2], excessive AR activation triggered by xenobiotic agonists accelerates diseases severity such as androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) and prostate cancer [3]. For this reason, AR is one of targets for testing drug toxicity, and drug candidates should be assayed for potential AR-mediated toxicity. There have been reports on experimental AR affinity assays of chemical compounds [4, 5]. Recently due to the advance of high-throughput techniques AR screening could be carried out at a large scale [6]. Nonetheless, experiment-based screening methods are still costly and time-consuming as well as it is not possible to cover the structural diversity of chemical compounds. To tackle down the limitation, computational AR-dependent toxicity prediction methods have been developed to save time and cost. However, their accuracies are not enough to completely replace experiments and thus they need to be improved further.

In 2018, a combination of three computational algorithms to predict agonist and antagonist activity on AR and thyroid hormone receptor was published [7]. Although the model predicted nuclear receptor agonist molecules with moderate performance, the model was not accurate enough to substitute experimental screening methods. To our knowledge, though there are several reports on docking-based AR agonist prediction [8, 9], there are no other machine-learning-based in silico approaches to predict AR agonist activity, which can be virtually carried out at high-throughput.

Generally, in silico approaches to predict biological activity of chemical compounds firstly converts a molecular structure into thousands of different molecular features [10]. Various molecular features have been introduced including static features such as physicochemical properties, and dynamic features such as molecular fingerprints. Various conversion methods have been developed for accurate feature generation [11]. Since the molecular features do not represent all the chemical and physical properties of chemical compounds, such conversion necessarily accompanies information loss. Thus, developing a novel conversion method and combining the method with conventional ones could enhance the performance of in silico models by minimizing information loss.

Convolutional neural network (CNN) is a class of deep neural network (DNN) algorithm mainly introduced for image classification [12]. CNN models can effectively extract and learn local features from images with fewer parameters compared with conventional DNN models, by employing multiple convolution and pooling layers [13]. With such advantages, CNN model has been employed to solve various problems including medical image classification [14] and facial expression recognition [15].

In this study, instead of the limited conventional molecular features, we employed the 2-D structure mimetic diagram of chemical compounds (ball-and-stick models) to construct a prediction model. CNN algorithm was introduced to classify molecular images into AR agonists or inactive compounds. We expected CNN model analyzed substructure of input molecules by itself by automatically extracting and learning features from input images. As a result, the constructed CNN-based in silico model successfully classified molecular images to AR agonists or inactive compound, which outperformed previous models in terms of overall accuracy.

Materials and methods

Construction of training dataset

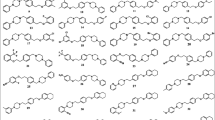

In Tox21 Data Challenge 2014, training dataset for AR-induced toxicity prediction was provided (PubChem AID 743040). In this study, we downloaded the dataset from Tox21 Data Challenge 2014 repository. It contains Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) [16], NCATS Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC) ID and agonist activity (active or inactive) of 9362 compounds. After removing duplicate compounds, we obtained 270 active agonists and 7198 inactive chemicals for AR. We used OpenBabel toolbox (version 2.4.0) [17] to convert compounds from SMILES format to 2-D ball-and-stick structure (Fig. 1). All structures were saved into PNG format, and further transformed into 200 (width) × 200 (height) × 3 (color channels) array with RGB values of each pixel.

Model construction

Convolutional neural network (CNN) algorithm was employed to construct a molecular image classification model for AR agonist screening. We constructed a CNN model with a feature extraction part and 1 fully connected output layer. Overall model architecture is shown in Fig. 2.

Feature extraction part consists of convolutional, dropout, pooling and batch normalization layers. Convolutional layers automatically search and extract representative features from input images with convolutional filters and activation function. Dropout, pooling and batch normalization layers were employed to prevent overfitting and reduce computational resource usage by reducing the number of features. After extraction part, representative features will be input features of dense neural network with single layer. As a result, inputted molecular image will be classified into AR agonist or inactive compound.

To enhance the overall performance of prediction model, we optimized two factors: learning rate and L2 regularization factor. Learning rate is a scalar value that determines training speed of the model and controls the rate of adaptation to changing input data. L2 regularization factor suppresses model from overfitting on training data. We evaluated with four learning rates (10− 3, 10− 4, 10− 5, 10− 6) and five L2 regularization factors (0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2), and constructed 20 different trained models.

The optimal parameters were determined by AUC, and then the threshold to classify AR-toxicity was further optimized by Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) since the training and evaluation datasets were highly unbalanced [18]. However, instead of selecting the highest AUC, we selected a trained model with high AUC and robust prediction accuracies. A trained model may not display robustness in prediction, so we traced AUC results epoch-by-epoch and selected a model that showed stable prediction accuracies and a high AUC.

Model validation

For model evaluation, we collected active and inactive AR agonists from the literature [7]. The dataset contained agonists, antagonists and inactive compounds for AR. A test dataset was constructed with 71 active AR agonists and 220 inactive compounds, excluding duplicated molecules and compounds included in training dataset. Prediction performance was calculated as MCC, AUC, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and positive predictive value (PPV).

We tested whether our model was able to predict AR agonists with high performance, which were collected from other bioassay results. Twenty-five compounds extracted from AR agonist bioassay (AID 639154) were used as a test dataset [19]. The dataset consisted of two active AR agonists and 23 inactive compounds, separated by a threshold of IC50 = 10 μ M.

Results and discussion

Training performance

To select the optimal hyperparameters of a CNN model, we constructed 20 models with different parameters. Prediction performances of the trained models in 10-fold cross-validation was recorded epoch by epoch. The parameters and resulting AUC values are shown in Table 1. From the result, the CNN model with learning rate of 10− 3 and L2 regularization factor of 1.0 showed the best AUC value (0.915).

The top four models were also analyzed in terms of robustness. As shown in the Fig. 3, under certain parameters the trained models showed unstable performances (fluctuation in AUC value), which represents that the models were overshoot by fast learning rates. Consequently, a learning rate of 10− 6, a regularization factor of 1.0, and epoch number of 429 were determined, which showed high AUC (0.902) and stable performance as well.

For further optimization, the optimal threshold value to classify active and inactive agonists was determined in terms of MCC, which is an appropriate index to show performance of classification on imbalanced datasets. The selected best model marked the highest MCC of 0.688 at the threshold of 0.66 was selected, and other classification performances under the threshold are listed in Table 2.

Model test

For the model test, we collected 71 active AR agonists and 220 inactive compounds from the literature [7]. Overall performance values are listed in Table 3. The test results also showed comparable performance with cross-validation result. Interestingly, PPV on the test dataset increased up to 0.882, which represents that once a compound is predicted to be an agonist, then it would be an agonist with high probability.

As another evaluation, we used AR agonist activity screening bioassay record as a test dataset. Yamamoto S et al. designed and synthesized a series of 4-phenylpyrrole derivatives from known AR antagonists to discover novel orally available AR antagonists as effective prostate cancer drugs. Antagonist and agonist activity of synthesized compounds were biologically evaluated and reported as a bioassay record (PubChem AID 639154) [19]. As shown in Fig. 4, most of compounds in the dataset are derived from 1-arylmethyl-4-phenylpyrrole and have almost same 2-D diagram. Although such similarity makes AR agonist detection difficult, our constructed model successfully classified all compound exactly, showing 100% accuracy. These results proved that our model can be used to predict AR agonist activity with high accuracy and molecular images can be another feature for predicting biological activities of chemical compounds.

Conclusion

We introduced a CNN-based model to predict molecular agonist activity for AR with a novel input data: 2-D chemical structure of molecules. Generally, CNN based image classification models can solve real-life problems: handwriting recognition, object recognition, and so on. We also employed the same strategy for image-based AR toxicity classification. Our model marked high performance (AUC = 0.902) in cross-validation and AUC of 0.783 on test dataset, outperforming the previous model (AUC = 0.756) based on classical classification algorithms and classical numerical features in 2018 [7].

We expect our approach can be utilized to predict various biological activities of chemical compounds, e.g. toxicity classifications, absorption classifications, etc. Our model proved that images could be another feature for classification.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AR:

-

Androgen receptor

- AUC:

-

Area under ROC curve

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural network

- MCC:

-

Matthews correlation coefficient

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- SEN:

-

Sensitivity

- SMILES:

-

Simplified molecular-input line-entry system

- SPE:

-

Specificity

References

Gelmann EP. Molecular biology of the androgen receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(13):3001–15.

Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G. Steroid hormone receptors: many actors in search of a plot. Cell. 1995;83(6):851–7.

Tan ME, Li J, Xu HE, Melcher K, Yong EL. Androgen receptor: structure, role in prostate cancer and drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(1):3.

Edwards JP, Higuchi RI, Winn DT, Pooley CL, Caferro TR, Hamann LG, Zhi L, Marschke KB, Goldman ME, Jones TK. Nonsteroidal androgen receptor agonists based on 4-(trifluoromethyl)-2H-pyrano [3, 2-g] quinolin-2-one. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9(7):1003–8.

Tamura H, Ishimoto Y, Fujikawa T, Aoyama H, Yoshikawa H, Akamatsu M. Structural basis for androgen receptor agonists and antagonists: interaction of SPEED 98-listed chemicals and related compounds with the androgen receptor based on an in vitro reporter gene assay and 3D-QSAR. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14(21):7160–74.

Lynch C, Sakamuru S, Huang R, Stavreva DA, Varticovski L, Hager GL, Judson RS, Houck KA, Kleinstreuer NC, Casey W, Paules RS, Simeonov A, Xia M. Identifying environmental chemicals as agonists of the androgen receptor by using a quantitative high-throughput screening platform. Toxicology. 2017;385:48–58.

Yan L, Zhang Q, Huang F, Nie W-W, Hu C-Q, Ying H-Z, Dong X-W, Zhao M-R. Ternary classification models for predicting hormonal activities of chemicals via nuclear receptors. Chem Phys Lett. 2018;706:360–6.

Ng HW, Zhang W, Shu M, Luo H, Ge W, Perkins R, Tong W, Hong H. Competitive molecular docking approach for predicting estrogen receptor subtype α agonists and antagonists. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(Supple 11):S4.

Wang X, Li X, Shi W, Wei S, Giesy JP, Yu H, Wang Y. Docking and CoMSIA studies on steroids and non-steroidal chemicals as androgen receptor ligands. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2013;89:143–9.

Randić M. Generalized molecular descriptors. J Math Chem. 1991;7(1):155–68.

Kearnes S, McCloskey K, Berndl M, Pande V, Riley P. Molecular graph convolutions: moving beyond fingerprints. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2016;30(8):595–608.

Sharma N, Jain V, Mishra A. An analysis of convolutional neural networks for image classification. Procedia Comput Sci. 2018;132:377–84.

Rawat W, Wang J. Deep convolutional neural networks for image classification: a comprehensive review. MIT Press. 2017;29(9):2352–449.

Kumar A, Kim J, Lyndon D, Fulham M, Feng D. An ensemble of fine-tuned convolutional neural networks for medical image classification. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2016;21(1):31–40.

Lawrence S, Giles CL, Tsoi AC, Back AD. Face recognition: a convolutional neural-network approach. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 1997;8(1):98–113.

Weininger D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1988;28(1):31–6.

O'Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3(1):33.

Boughorbel S, Jarray F, El-Anbari M. Optimal classifier for imbalanced data using Matthews correlation coefficient metric. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0177678.

Yamamoto S, Matsunaga N, Hitaka T, Yamada M, Hara T, Miyazaki J, Santou T, Kusaka M, Yamaoka M, Kanzaki N, Furuya S, Tasaka A, Hamamura K, Ito M. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 4-phenylpyrrole derivatives as novel androgen receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20(1):422–34.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

About this Supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Bioinformatics, Volume 21 Supplement 5, 2020: Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Data and Text Mining in Biomedical Informatics (DTMBIO 2019). The full contents of the supplement are available at https://bmcbioinformatics.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-21-supplement-5.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (No. NRF-2019M3E5D4065682 and No. NRF-2018R1A5A1025077). This research was also supported by the Chung-Ang University Research Scholarship Grants in 2017. Publication costs were supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (No. NRF-2019M3E5D4065682). The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M Y developed the prediction models and conducted the evaluation. J L and Y L assisted to develop the prediction models. M Y and D N wrote and revised the manuscript. D N supervised the study. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, MS., Lee, J., Lee, Y. et al. 2-D chemical structure image-based in silico model to predict agonist activity for androgen receptor. BMC Bioinformatics 21 (Suppl 5), 245 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-020-03588-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-020-03588-1