Abstract

Background

Loop diuretics are common therapy for emergency department (ED) patients with acute heart failure (AHF). Diuretic resistance (DR) is a term used to describe blunted natriuretic response to loop diuretics. It would be important to detect DR prior to it becoming clinically apparent, so early interventions can be initiated. However, several definitions have been proposed, and it is not clear if they identify similar patients. We compared these definitions and described the clinical characteristics of patients who fulfilled them.

Methods

To qualify for this secondary analysis of 1033 ED patients with AHF, all patients needed to receive intravenous diuretics in the ED and have urine available within 24 h of their ED evaluation. A poor diuretic response, suggesting DR, was characterized by (1) a fractional sodium excretion (FeNa) of less than 0.2%; (2) spot urinary sodium of less than 50 meq/L; and (3) a urinary Na/K ratio <1.0. McNemar’s test was used to compare the different cohorts identified by the three definitions. Secondary analyses evaluated associations between each DR definition and hospital length of stay (LOS), ED revisits and rehospitalizations for AHF, and mortality using the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and linear regression or Pearson chi-square test and logistic regression, as appropriate.

Results

The median age of the 187 patients was 64, and 50% were African-American. There were 5.9% of patients with a FeNa less than 0.2%, 17.1% had urinary sodium less than 50 meq/L, and 10.7% had a urinary Na/K ratio <1.0. The three definitions identified significantly different patients with very little overlap (p < 0.02 for all comparisons). There were 37 (19.8%) patients who were readmitted to the ED or hospital or died within 30 days of ED evaluation. Patients with spot urinary sodium less than 50 meq/L were more likely to be readmitted (p = 0.03).

Conclusions

The patient proportion with poor natriuresis and DR varies depending on the definition used. Early ED therapy would be impacted at different rates if clinical decisions are made based on these definitions. These findings need to be further explored in a prospective ED-based study.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00508638

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over the last decade, there have been nearly one million annual emergency department (ED) visits for acute heart failure (AHF) [1]. Intravenous loop diuretics are commonly administered to promote diuresis, natriuresis, and congestion relief in these patients [2, 3]. While diuretics often lead to symptomatic improvement, they have not resulted in decreases in mortality or hospital readmission, and some studies have found that their use in hospitalized patients has been associated with detrimental outcomes [4].

In AHF, decreased cardiac output leads to arterial underfilling, increased renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activity, and increased proximal tubule sodium reabsorption [5]. Retention of sodium and water due to inadequate natriuresis and diuresis are hallmarks of heart failure (HF). Patients with HF have a markedly reduced rate of renal sodium excretion, and cumulative sodium retention has been closely correlated with an increase in body weight [6]. Loop diuretics are administered to inhibit sodium reabsorption in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and are intended to increase natriuresis. When loop diuretics are effective, the urinary sodium rises and the urinary potassium falls. Poor gut absorption of orally administered loop diuretics, decreased delivery to molecular targets, low serum albumin, renal tubular hypertrophy, and circulating organic acids inhibiting the organic anion transporter all lead to a diminished effect of diuretics, resulting in impaired urinary sodium excretion [7]. Even when diuretics are given intravenously, diuretic “braking” can be encountered, negating intended natriuresis and contributing to diuretic resistance in patients with AHF. [7]

Furthermore, a subset of HF patients with a decreased response to diuretic therapy are termed “diuretic resistant” and have a blunted natriuretic response, though the frequency of this phenomenon is not well established [7]. Inadequate natriuresis and diuresis in patients who develop diuretic resistance have been associated with prolonged hospital lengths of stay and increased mortality [8, 9]. While clinical characteristics of patients with diuretic resistance have been identified, a reliable prospective measure identifying those who have suboptimal diuretic and natriuretic responsiveness has not been extensively studied [10]. The inability to predict diuretic responsiveness may delay intensified therapy, thus prolonging hospitalization and delaying decongestion.

Until recently, investigations had focused on defining diuretic and natriuretic responsiveness based on change in body weight or urine output relative to the dose of furosemide administered [8, 9, 11, 12]. These definitions require up to 96 h to identify diuretic resistance, do not allow a real-time measure of response to diuretic therapy, and have not been conducted in the ED [10]. Without an early definition of diuretic and natriuretic responsiveness, it is difficult to design prospective ED-based studies of alternative therapies to loop diuretics, such as diuretic combinations, natriuretic doses of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, vasoactive medications, and ultrafiltration.

The purpose of the study was not to determine the ideal definition for diuretic resistance but to better understand how the different definitions compare. Definitions generally utilize inexpensive and rapidly available urine electrolytes. The fractional sodium excretion (FeNa) is the percentage of sodium filtered by the kidney and excreted in the urine; it has been used to assess natriuresis in HF patients [13,14,15]. Baseline FeNa is reduced to less than 1.0% in patients with HF, and a baseline FeNa of less than 0.2% is associated with poor natriuretic response [7,14,, 13–15]. Further, in liver cirrhosis, a condition also associated with poor natriuretic response to diuretics, a natriuresis lower than 50 meq in 8 h after a single intravenous dose of loop diuretics was a predictor of refractory ascites and has been used to define poor natriuretic responsiveness in this population [16]. An exploratory definition of a urine Na/K ratio <1.0 was included based on our suspicion that patients with poor natriuretic responsiveness would have disproportionately low ratios of urinary sodium relative to potassium. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and biases of these observations is fundamental to defining diuretic resistance. To better understand these concepts, we directly compared definitions of diuretic resistance in a cohort enrolled in a prospective observational study in ED patients with AHF. A secondary aim was to evaluate hospital length of stay (LOS), 30-day mortality, repeat ED visits, and rehospitalizations for AHF in patients who fulfilled each of the definitions.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board as exempt from review (IRB# 150508). Our subjects consisted of a subset of patients with AHF enrolled in a prospective ED cohort study [2, 17]. Eligible patients received at least one dose of intravenous diuretics and were admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of AHF. Urine was collected within 12–24 h of their ED visit and analyzed for potassium, sodium, and creatinine. Patients were contacted by telephone and had a medical record review performed to determine 30-day outcomes in the prior cohort study.

Measures of diuretic resistance

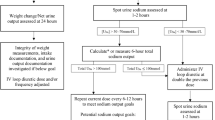

For our analysis, diuretic resistance was defined using three separate criteria: (1) a baseline FeNa of less than 0.2% [7,14,, 13–15]; (2) a spot urinary sodium of less than 50 meq/L at 12–24-h urine measurement [16]; and (3) a spot urine Na/K ratio <1.0.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including median and percentages, were used to describe the study population and time of diuretic administration to acquisition of urine. To assess agreement between the definitions of diuretic resistance, we used Cohen’s Kappa coefficient and McNemar’s test. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and linear regression were used to assess the association of the biomarkers for diuretic resistance with hospital LOS; Pearson chi-square tests and logistic regression were used to assess the association of the diuretic resistance with AHF-related ED revisits, rehospitalizations for AHF, and mortality within 30 days of the index ED visit. For all regressions, the biomarker was kept continuous and fit with restricted cubic splines (three knots) to relax the linearity assumption.

Results

Our study included 187 patients (Table 1). Sixty-five percent were male, and the median age was 64 years (interquartile range (IQR) 55, 73). The median systolic blood pressure (SBP) was 149 mmHg (IQR = 130, 178), and 50% were African-American. The median blood urea nitrogen and creatinine in our cohort were 22 mg/dL (IQR = 15, 35) and 1.4 mg/dL (IQR = 1.1, 2.1), respectively. The median b-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) was 1232 pg/mL (IQR = 545, 2198), and 33% had an ejection fraction (EF) greater than 55% on echocardiogram. The median time from diuretic administration to collection of urine for electrolyte measurement was 8.3 h (IQR = 3.0, 12.9).

Measures of natriuretic responsiveness

We identified 11 (5.9%) patients with diuretic resistance based on a FeNa of <0.2% (Additional file 1). These subjects, compared to those without resistance, had similar ED-measured SBP (142 vs 149 mmHg, respectively, p = 0.24) and BNP (894 vs 1249 pg/mL, p = 0.14) but were more likely to have better renal function (serum Cr 1.0 vs 1.4 mg/dL, p = 0.007). There were 32 (17.1%) patients defined as diuretic resistant based on spot urinary sodium value <50 meq/L. Using this definition, diuretic resistant and non-diuretic resistant patients had similar ED-measured renal function (serum Cr 1.4 vs 1.4 mg/dL, respectively, p = 0.57), SBP (147 vs 149 mmHg, respectively, p = 0.79), and BNP levels (1468 vs 1217 pg/mL, p = 0.15). Despite approximately one-third of both groups receiving 80 mg or greater of intravenous furosemide, the median urinary output 12–24 h later in those who fulfilled this definition was nearly 900 mL less than those who did not (p = 0.005) (Table 2). Twenty (10.7%) patients were diuretic resistant using a urinary Na/K ratio of <1.0 (Additional file 2). Patients with and without diuretic resistance based on this definition had similar baseline characteristics, but those of AA race (25 vs 53%, p = 0.019) were much less likely to be diuretic resistant.

A comparison between our three definitions of diuretic resistance (Tables 3, 4, and 5) found each identified a significantly different (p ≤ 0.02) patient cohort. The Kappa for agreement between FeNa and measured urinary sodium was 0.41 (95% CI 0.22–0.6). For FeNa and urine Na/K ratio, the Kappa was 0.62 (95% CI 0.41–0.82). Finally, for urine Na/K ratio and measured urinary sodium concentration, the Kappa was 0.60 (95% CI 0.44–0.77)

Hospital LOS, AHF revisits, AHF readmission, and mortality

There was no difference in hospital LOS, ED revisits or hospital readmissions for AHF, or death between those who did and did not fulfill the definition of diuretic resistance based on FeNa <0.2%. Patients who were diuretic resistant based on a spot urinary Na <50 meq/L had a higher rate of hospital readmission for AHF compared to those who were not (28 vs 13%, p = 0.03). While diuretic resistance as defined by the dichotomized urinary Na <50 meq/L failed to show significant associations with LOS, predicted LOS and hospital readmission from the linear regression suggested decreasing LOS and hospital readmission with increasing urinary sodium. (Table 2, Fig. 1a, b). Patients fulfilling the third criterion standard for diuretic resistance, a urine Na/K ratio of <1, had no differences in LOS, 30-day ED revisit, or hospital readmission for AHF versus those with Na/K ratios of >1.

Discussion

We directly compared three definitions of diuretic resistance in 187 ED patients admitted for AHF. Our investigation is the only study to date performed in ED patients after their first dose of diuretic, as other studies focused on inpatients who had received multiple doses of diuretics. Our three definitions of diuretic resistance identified distinctly different patient cohorts, and the prevalence varied widely based on these definitions. Diuretic resistance in our population ranged from 5.9% using FeNa <0.2 to 17.1% using spot urinary Na <50 meq/L. This is an important finding as we seek to identify diuretic resistance earlier in a patient’s course; the definition utilized would impact the proportion of patients identified. Those who fulfilled a definition of diuretic resistance based on urine Na <50 meq/L were more likely to have an increased hospital LOS and an increased proportion of AHF readmissions. This has been seen in prior inpatient studies as well [9, 18].

Traditional definitions have required greater than 24 h to classify patients as diuretic resistant by using change in weight divided by milligram equivalent of loop diuretic [9, 19]. A formula was recently derived to quantify the relationship between early measures of urinary sodium and 6-h natriuresis [10]. However, these patients were enrolled a median of 4 days after hospital admission and would not be reflective of the more acute, early diuresis seen in an ED AHF population. The timeframe for definitions we investigated was less than 24 h from ED presentation.

Early identification of ED patients with AHF who will have a suboptimal response to traditional diuretic dosing could help guide therapy and may have implications regarding hospital LOS, readmission, and the cost of care. Those patients identified early in their ED stay as non-responders could be given a higher dose of loop diuretic, a thiazide, aldosterone antagonist, or vasoactive therapy as a means of decongestive therapy. However, other factors need to be considered when evaluating readmission, such as dietary and medication non-adherence. Further, identification of diuretic resistance was not consistent across the investigated definitions, highlighting the importance of developing a standard and objective definition of natriuretic responsiveness.

Our investigation has several limitations. We analyzed a subset of patients from a prospective cohort study performed in the ED. Diuretic dosing was at the discretion of the treating physician and was not standardized; thus, our results could have been influenced by under dosing. In addition, we did not consider other therapies the patient may have received in addition to loop diuretics. Further, the median time from initial ED diuretic dose to the time of urine electrolyte analysis in our study was 8.3 h with an interquartile range of 3–12.9 h. The majority of natriuresis occurs within the first 180 min following parenteral administration of loop diuretics [20], suggesting the majority of natriuresis may have occurred by the time our urine samples were collected and analyzed. However, many of our patients still had urinary sodium measures consistent with optimal daily natriuresis, suggesting these patients had a brisk and appropriate natriuretic response. Our patients did not have a bladder scan prior to diuretic administration and were not required to have an indwelling urinary catheter placed, nor did the majority receive one as part of routine ED practice; therefore, total urinary output documentation may be less accurate. In addition, if patients did have a urinary catheter placed in the ED, their measured urinary sodium at time of collection could be inaccurate secondary to residual urine in their Foley bag. Because this was a retrospective study, we are unable to classify the severity of the AHF exacerbations in our study. Measurements such as home diuretic dose, time from last diuretic dose, and weight gain compared to dry weight would have added valuable information regarding the extent of baseline disease and the severity of the exacerbation that prompted the patient to seek treatment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, depending on the definition utilized, the proportion of patients identified as diuretic resistant varies anywhere from 6 to 17.1%. This may impact treatment decisions, especially if changes in therapy are made early in a patient’s course based on these definitions, prior to diuretic resistance becoming clinically apparent. The measure most predictive of diuretic resistance in our investigation was urinary sodium <50 meq/L. These patients may have an increase in hospital readmission for AHF and trends toward a longer inpatient LOS. Measuring urine electrolytes and predicting natriuretic response shortly after initial ED treatment present an opportunity to identify patients who may need intensified therapy early in their hospital course to provide adequate decongestion. These findings need to be explored in a larger cohort of ED patients who receive a standardized initial diuretic regimen, continuous urinary measurements over a 6-h time period, and adjust for other confounders that may contribute to LOS and readmission. This will enable us to quantify natriuresis and predict natriuretic responsiveness via urinary electrolyte patterns, determining the earliest time point during an ED presentation that diuretic resistance can be identified.

Abbreviations

- AHF:

-

Acute heart failure

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- FeNa:

-

Fractional excretion of sodium

- K:

-

Potassium

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- Na:

-

Sodium

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

References

Storrow AB, Jenkins CA, Self WH, Alexander PT, Barrett TW, Han JH, et al. The burden of acute heart failure on U.S. emergency departments. JACC Heart fail. 2014;2(3):269–77. Epub 2014/06/24.

Collins SP, Jenkins CA, Harrell Jr FE, Liu D, Miller KF, Lindsell CJ, et al. Identification of emergency department patients with acute heart failure at low risk for 30-day adverse events: the STRATIFY decision tool. JACC Heart fail. 2015;3(10):737–47. Epub 2015/10/10.

Adams Jr KF, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, LeJemtel TH, Costanzo MR, Abraham WT, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). Am Heart J. 2005;149(2):209–16. Epub 2005/04/23.

Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, Redfield MM, Stevenson LW, Goldsmith SR, et al. Diuretic strategies in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):797–805. Epub 2011/03/04.

ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Damman K, Hillege HL, Navis G, Voors AA. Diuretic response in acute heart failure-pathophysiology, evaluation, and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(3):184–92.

Braunwald E, Plauth Jr WH, Morrow AG. A method for the detection and quantification of impaired sodium excretion. Results of an oral sodium tolerance test in normal subjects and in patients with heart disease. Circulation. 1965;32:223–31. Epub 1965/08/01.

Ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Damman K, Hillege HL, Navis G, Voors AA. Diuretic response in acute heart failure-pathophysiology, evaluation, and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015. Epub 2015/01/07.

ter Maaten JM, Dunning AM, Valente MA, Damman K, Ezekowitz JA, Califf RM, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure—an analysis from ASCEND-HF. Am Heart J. 2015;170(2):313–21. Epub 2015/08/25.

Voors AA, Davison BA, Teerlink JR, Felker GM, Cotter G, Filippatos G, et al. Diuretic response in patients with acute decompensated heart failure: characteristics and clinical outcome—an analysis from RELAX-AHF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(11):1230–40. Epub 2014/10/08.

Testani JM, Hanberg JS, Cheng S, Rao V, Onyebeke C, Laur O, et al. Rapid and highly accurate prediction of poor loop diuretic natriuretic response in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(1):e002370. Epub 2016/01/02.

Valente MA, Voors AA, Damman K, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Massie BM, O'Connor CM, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure: clinical characteristics and prognostic significance. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(19):1284–93. Epub 2014/03/04.

Testani JM, Brisco MA, Turner JM, Spatz ES, Bellumkonda L, Parikh CR, et al. Loop diuretic efficiency: a metric of diuretic responsiveness with prognostic importance in acute decompensated heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(2):261–70. Epub 2014/01/01.

Gabrielsen A, Bie P, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Christensen NJ, Warberg J, Dige-Petersen H, et al. Neuroendocrine and renal effects of intravascular volume expansion in compensated heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281(2):R459–6.

Fifer MA, Molina CR, Quiroz AC, Giles TD, Herrmann HC, De Scheerder IR, et al. Hemodynamic and renal effects of atrial natriuretic peptide in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65(3):211–6. Epub 1990/01/15.

Dormans TP, Gerlag PG. Combination of high-dose furosemide and hydrochlorothiazide in the treatment of refractory congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(12):1867–74. Epub 1996/12/01.

Spahr L, Villeneuve JP, Tran HK, Pomier-Layrargues G. Furosemide-induced natriuresis as a test to identify cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):28–31. Epub 2000/12/22.

Collins SP, Lindsell CJ, Jenkins CA, Harrell FE, Fermann GJ, Miller KF, et al. Risk stratification in acute heart failure: rationale and design of the STRATIFY and DECIDE studies. Am Heart J. 2012;164(6):825–34. Epub 2012/12/01.

Palazzuoli A, Testani JM, Ruocco G, Pellegrini M, Ronco C, Nuti R. Different diuretic dose and response in acute decompensated heart failure: clinical characteristics and prognostic significance. Int J Cardiol. 2016;224:213–9.

ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Metra M, Bruno N, O'Connor CM, Ponikowski P, et al. A combined clinical and biomarker approach to predict diuretic response in acute heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016;105(2):145–53. Epub 2015/08/19.

Kelly RA, Wilcox CS, Mitch WE, Meyer TW, Souney PF, Rayment CM, et al. Response of the kidney to furosemide. II. Effect of captopril on sodium balance. Kidney Int. 1983;24(2):233–9. Epub 1983/08/01.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Jennifer Starnes for her assistance in the manuscript preparation.

Funding

This work was supported through a Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VITCR) Award (#VR13043).

Authors’ contributions

AD contributed to the developed concept, drafting of paper, and final manuscript review; CJ contributed to the statistical analysis, drafting of paper, and final manuscript review; ABS contributed to the concept development, drafting of paper, and final manuscript review; JL contributed to the concept development, drafting of paper, and final manuscript review; GJF contributed to the drafting of paper and final manuscript review; KM contributed to the data handling and analysis, drafting of paper, and final manuscript review; MS contributed to the data handling and analysis, drafting of paper, and final manuscript review; SPC contributed to the concept development, drafting of paper, and final manuscript review and is responsible for final contents of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Alan B. Storrow, MD, received grant research support from Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, NIH/NHLBI, Abbott Diagnostics, Roche Diagnostics, Beckman-Coulter, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals and consultant support/other from Roche Diagnostics, Beckman-Coulter, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and Trevena. JoAnn Lindenfeld, MD, received grant research support from Novartis and consultant support/other from St. Jude, Abbott, Relypsa, RESMED, Cardiokinetix, and CVRx. Gregory J. Fermann, MD, received grant research support from PCORI, Cardiorentis, Novartis, Cardioxyl, Siemens, Radiometer, Portola, Pfizer, and Nanodetection and consultant support/other from the Speakers’ Bureau for Janssen. Sean P. Collins, MD, MSc, received grant research support from NIH/NHLBI, PCORI, Cardiorentis, Novartis, and Cardioxyl and consultant support/other from Novartis, Trevena, Cardiorentis, Cardioxyl, and Siemens. Andrew Doering, MD, Cathy Jenkins, MS, Karen Miller, and Matthew Sperling declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Descriptive statistics by diuretic resistance assessed using a FeNa <0.2%. (DOC 65 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Descriptive statistics by diuretic resistance assessed using a Na/K ratio < 1. (DOC 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Doering, A., Jenkins, C.A., Storrow, A.B. et al. Markers of diuretic resistance in emergency department patients with acute heart failure. Int J Emerg Med 10, 17 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-017-0143-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-017-0143-x