Abstract

Background

Scrub typhus is an acute and febrile infectious disease caused by the Gram-negative α-proteobacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi from the family Rickettsiaceae that is widely distributed in Northern, Southern and Eastern Asia. In the present study, we analysed the serum proteome of scrub typhus patients to investigate specific clinical protein patterns in an attempt to explain pathophysiology and discover potential biomarkers of infection.

Methods

Serum samples were collected from three patients (before and after treatment with antibiotics) and three healthy subjects. One-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was performed to identify differentially abundant proteins using quantitative proteomic approaches. Bioinformatic analysis was then performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Results

Proteomic analysis identified 236 serum proteins, of which 32 were differentially expressed in normal subjects, naive scrub typhus patients and patients treated with antibiotics. Comparative bioinformatic analysis of the identified proteins revealed up-regulation of proteins involved in immune responses, especially complement system, following infection with O. tsutsugamushi, and normal expression was largely rescued by antibiotic treatment.

Conclusions

This is the first proteomic study of clinical serum samples from scrub typhus patients. Proteomic analysis identified changes in protein expression upon infection with O. tsutsugamushi and following antibiotic treatment. Our results provide valuable information for further investigation of scrub typhus therapy and diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Scrub typhus (tsutsugamushi disease) is a mite-borne infectious disease caused by the Gram-negative α-proteobacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi that is transmitted through the bite of an infected chigger (Trombiculidae mite) [1]. After a bite from an infected chigger, a characteristic necrotic inoculation lesion, termed eschar, can develop, and the microorganism then spreads through the lymphatic fluid and blood, causing systemic manifestations including fever, headache, myalgia, lymphadenopathy and skin rash. Especially in untreated cases, patients develop complications with systemic involvement and disseminated vasculitis, including septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal failure, meningitis, myocarditis, gastrointestinal bleeding and multiorgan dysfunctions [2, 3]. Scrub typhus is endemic in the ‘tsutsugamsuhi triangle’ area, which extends from Northern Japan and far Eastern Russia in the North, to Northern Australia in the South, and to Pakistan and Afghanistan in the East [4,5,6]. Over one billion people are currently living in risk areas, and approximately one million cases occur annually worldwide [7]. The average case-fatality rate is usually ~ 10%, but can be as high as 35% if antimicrobial treatment is delayed. In the pre-antibiotic era, case-fatality ratios may have been as high as 50% [8]. Therefore, early diagnosis of scrub typhus is essential to prevent complications and to reduce the mortality rate.

The main goal of proteomic studies is to elucidate protein expression and identify changes under the influence of biological perturbations such as diseases or drug treatment [9, 10]. The information obtained from such analyses provides valuable information on pathophysiology and potential diagnostic biomarkers of disease [11]. Since the genome sequence of O. tsutsugamushi was published [12], several proteomic studies have focused on identifying proteins. The first proteomic analysis involved 2D liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)-based comparison of protein expression, and 14 proteins were shown to be differentially expressed in antibiotic-sensitive and -insensitive O. tsutsugamushi [13]. Kishimoto and colleagues also performed shotgun proteomics analysis of O. tsutsugamushi, which revealed specific characteristics of this obligate intracellular bacterial species, and identified potential immunogenic factors such as type IV secretion system proteins [14]. More recently, comprehensive analysis of global gene and protein expression in O. tsutsugamushi in fibroblasts and macrophages showed how the pathogen responds in different types of host cells [15].

Although previous proteomic studies on O. tsutsugamushi provided some evidence about the pathophysiology of scrub typhus, information about diagnostic markers is lacking. Currently, complement fixation is one the earliest tests for diagnosis of scrub typhus [2, 16, 17]. At present, there is no diagnostic test of pathogenic antigen generated by O. tsutsugamushi. Moreover, proteomic analysis of O. tsutsugamushi directly isolated from scrub typhus patients has not been successfully performed, presumably because O. tsutsugamushi proteins are present at low concentrations in the blood. In the present study, as the first step in proteomic analysis of scrub typhus patients, we investigated the serum proteome to elucidate physiological changes caused by infection, both before and after antibiotic treatment.

Methods

Patients and clinical samples

The diagnosis of patients with scrub typhus was confirmed by a positive IgM titre ≥ 1:160 against O. tsutsugamushi, or a fourfold or greater rise in the indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA, Green Cross Reference Lab., Yongin, South Korea). Detailed patient information is listed in Table 1. Blood was collected from scrub typhus patients, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared for PCR validation of O. tsutsugamushi infection. For proteomic analysis, blood serum samples were prepared from three scrub typhus patients before and after antibiotic treatment. Doxycycline 200 mg/day was used to treat for 5 to 7 days. First blood sample was collected at emergency room before antibiotics administration and second sample was 5 to 7 days after antibiotics. Sera from three healthy subjects were used as negative infection controls.

PCR

Standard PCR was performed with 20 ng/µl DNA from PBMCs. For nested PCR, 2 µl of a 100-fold diluted standard PCR mixture was used as template. Primers used for PCR amplification of a gene encoding a 56 kDa protein were as follows: standard PCR (862 bp), 5′-CAATGTCTGCGTTGTCGTTGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAGATGCACTATTAGGCAA-3′ (reverse); nested PCR (509 bp), 5′-CCAGGATTTAGAGCAGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGCTAGGTTTATTATCAT-3′ (reverse).

Preparation of clinical serum samples for proteomic analysis

For proteomic analysis, albumin and IgG were removed from clinical serum samples using ProteoPrep Immunoaffinity Albumin and IgG Depletion Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After column equilibration, 100 µl of serum sample (diluted with 50 µl of dilution solution) was loaded on the column and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The eluate was collected by centrifugation at 8000×g for 1 min, and reapplied to the same spin column. The second elute was collected and used for proteomic analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and tryptic digestion

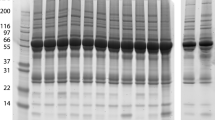

Prepared clinical serum samples (10 µg) were resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (1 M TRIS–HCl pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 1% bromophenol blue, glycerol, β-mercaptoethanol) and boiled for 10 min. Samples were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 and fractionated according to molecular weight. Tryptic in-gel digestion was conducted according to a previous procedure [18]. Digested peptides were extracted with extraction solution consisting of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 50% acetonitrile and 5% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and dried. For LC–MS/MS analysis, samples were dissolved in 0.5% TFA.

Proteomic analysis by LC–MS/MS analysis

Tryptic peptide samples (5 µl) were separated using an Ultimate 3000 UPLC system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) connected to a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ion source (Dionex). Peptides were eluted from the column and directed onto a 15 cm × 75 μm i.d. Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 reversed-phase column (Thermo Scientific) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Peptides were eluted by a gradient of 0–65% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid for 180 min. All MS and MS/MS spectra obtained using the Q Exactive Plus Orbitrap mass spectrometer were acquired in the data-dependent top10 mode, with automatic switching between full scan MS and MS/MS acquisition. Survey full scan MS spectra (m/z 150-2,000) were acquired in the orbitrap at a resolution of 70,000 (m/z 200) after accumulation of ions to a 1 × 106 target value based on predictive automatic gain control (AGC) from the previous full scan. MS/MS spectra were searched with MASCOT v2.4 (Matrix Science, Inc., Boston, MA, USA) using the UniProt human database for protein identification. MS/MS search parameters were set as follows: carbamidomethylation of cysteines, oxidation of methionines, two missed trypsin cleavages, mass tolerance for parent ion and fragment ion within 10 ppm, p value < 0.01 of the significant threshold. The exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) was generated using MASCOT, and mol% was calculated according to emPAI values [19]. MS/MS analysis was performed at least three times for each sample.

Statistical analysis and bioinformatics

Analysis was performed only on proteins that were detected more than two times from triplicate experiments for each sample. Differentially expressed proteins among the three groups were identified using Kruskal–Wallis tests. Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests were also performed to identify differentially expressed proteins within each group. Proteins were considered significantly differentially expressed when the p-value was less than 0.05 as calculated using R (http://www.r-project.org). All identified proteins were subjected to query canonical pathway analysis using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) tool (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis/).

Results and discussion

Evaluation of clinical samples

Sera from three scrub typhus patients were used for proteomic analysis. We collected blood from patients before and after antibiotic treatment. To confirm the quality of clinical blood samples from scrub typhus patients, PBMCs were isolated from blood, and the presence of pathogen was evaluated by nested PCR. The results showed that all three patients were positive for a specific scrub typhus gene encoding a 56 kDa protein, confirming infection by O. tsutsugamushi (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Proteomic analysis

To identify host proteins affected by scrub typhus infection, serum samples were prepared from normal subjects (controls), naive patients (before antibiotic treatment) and treated patients (after antibiotic treatment), then analysed by GeLC-MS/MS. From the proteomic analysis, 174, 155 and 143 human proteins were identified in the serum of normal subjects, naive scrub typhus patients and treated patients, respectively (Fig. 1 and Additional file 2: Table S1). Following infection with O. tsutsugamushi, expression of 70 proteins was significantly up-regulated, and expression of 94 proteins was down-regulated, compared with normal subjects (Table 2). After antibiotic treatment, 26 proteins were up-regulated and 36 proteins were down-regulated in treated patients relative to naive patients (Table 2). These proteins could be useful for investigating the pathophysiology of scrub typhus at the molecular level, and for discovering diagnostic biomarkers of O. tsutsugamushi infection. The quantitative results also revealed that the number of proteins expressed at similar levels in normal subjects and naive patients was 60 (26.8%), while the number between naive patients and treated patients was 113 (64.6%), indicating that protein expression was more similar between treated patients and naive patients than between treated patients and normal subjects (Table 2). This may suggest that treated patients are in the process of recovery, but not fully recovered.

Comparative analysis of canonical pathways

Discovery of canonical pathways enriched in different conditions and investigation of their differences upon infection with O. tsutsugamushi could provide potential information on the pathophysiology of scrub typhus. To this end, the identified proteins were analysed using the IPA bioinformatics tool. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the identified proteins are mainly involved in immune responses. In all groups, acute phage response signalling and complement system were ranked in the top five in the canonical pathway (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). In addition, proteins related to LXR/RXR activation, FXR/RXR activation and coagulation system were enriched in all samples (Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

To better understand the differences in expression of proteins and changes in the canonical pathways following infection with O. tsutsugamushi and subsequent antibiotic treatment, we compared the identified proteins and their enriched canonical pathways. The results revealed dynamic changes in the expression of proteins involved in immune responses (Fig. 2). In particular, expression of proteins associated with complement system was up-regulated by infection with O. tsutsugamushi (Fig. 2a) and down-regulated by antibiotic treatment (Fig. 2b). Investigation of signalling pathways also confirmed that complement system was significantly activated in scrub typhus patients, and activity was down-regulated by antibiotic treatment (Fig. 3).

Top 10 canonical pathways most significantly altered in naive scrub typhus patients compared with normal subjects (a) and in patients treated with antibiotics compared with naive patients (b). The stacked bar chart displays the percentage of proteins up-regulated (red) and down-regulated (green), and of proteins not overlapping with the dataset (white), in each canonical pathway. The numerical value at the top of each bar represents the total number of genes in the canonical pathway. The secondary y-axis (right) shows the −log of the p value calculated by the Benjamini–Hochberg method

Complement system is a canonical pathway significantly altered in naive scrub typhus patients compared with normal subjects (a) and in patients treated with antibiotics compared with naive patients (b). Red indicates up-regulated proteins, and green indicates down-regulated proteins. The colour intensity corresponds to the degree of up- or down-regulation (fold change). White represents proteins known to be part of the pathway but not identified in the proteomic analysis

Differentially expressed proteins

Next, we identified proteins displaying statistically significant differential expression between the three groups, and 32 differentially expressed proteins were identified (Table 3), of which 27 were up-regulated by infection with O. tsutsugamushi and down-regulated by antibiotic treatment. Representative proteins up-regulated in naive patients include serum amyloid proteins, complement component proteins, protein S100-A8 and C-reactive protein, which are mainly related to immune responses (Table 3). Up-regulation of immune responses is expected since scrub typhus infection induces a combination of non-specific symptoms that overlap with other infections [20]. Interestingly, platelet factor 4 was exclusively expressed in scrub typhus patients (Table 3). This small cytokine is secreted from platelets during platelet aggregation, and promotes blood coagulation [21, 22]. Recent studies reported that blood coagulation is activated by infection with O. tsutsugamushi [23,24,25]. Five proteins, serotransferrin, tetranectin, ficolin-3, selenoprotein P and adiponectin, were down-regulated in the serum of scrub typhus patients and up-regulated in patients treated with antibiotics (Table 3). Proteins displaying differential expression among normal subjects, naive patients and treated patients could be potential biomarkers for diagnosis and/or prediction of therapy responses during scrub typhus infection.

Proteins related to immune responses

For more detailed investigation of proteins related to immune responses, protein network analysis was performed. The results clearly showed that expression levels of proteins involved in acute phase response signalling and complement system were up-regulated by infection with O. tsutsugamushi (Fig. 4a) and down-regulated by treatment with the antibiotic doxycycline (Fig. 4b). Acute phase response signalling is a rapid inflammatory response that provides protection against pathogens using non-specific defence mechanisms [26]. We also found that proteins involved in inflammation, such as serum amyloid proteins, protein S100-A8 and C-reactive protein, were up-regulated in naive patients (Table 3).

Proteins related to immune responses. Protein network analysis reveals proteins related to acute phase response signalling and the complement system in naive scrub typhus patients compared with normal subjects (a) and in patients treated with antibiotics compared with naive patients (b). Red indicates up-regulated proteins, and green indicates down-regulated proteins. The colour intensity corresponds to the degree of up- or down-regulation (fold change)

The complement system is part of the innate immune system that enhances the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from the host organism, promotes inflammation and attacks the plasma membrane of the pathogen [27]. Our results showed that, among the 32 differentially expressed proteins, six of those up-regulated were complement component proteins (Table 3). Proteomic analysis also revealed that the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor was exclusively expressed following infection with O. tsutsugamushi (Table 3). The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor facilitates the secretion of IgA and IgM [28]. It is well known that both IgM and IgG initiate complement system activation [29]. Therefore, infection by O. tsutsugamushi induces IgM production, and this may lead to the expression of complement component proteins and activation of complement system, resulting in activation of the innate immune system, including inflammation.

Conclusions

In this study, we performed proteomic analysis of blood serum from scrub typhus patients to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms and discover potential diagnostic biomarkers for scrub typhus infection. Comparative analysis revealed that proteins involved in immune responses and blood coagulation were dynamically regulated following infection with O. tsutsugamushi and subsequent antibiotic treatment. In particular, complement system was activated in scrub typhus patients. We also discovered proteins that are differentially expressed among normal subjects, naive patients and patients treated with antibiotics. To our knowledge, this is the first analytical study of clinical samples from scrub typhus patients. Our results provide valuable information for further investigation of scrub typhus therapy and diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- aPTT:

-

activated partial thromboplastin time

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- PBMC:

-

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- FXR:

-

frarnesoid X receptor

- GeLC-MS/MS:

-

one-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- INR:

-

international normalized ratio

- LXR:

-

liver X receptor

- PT:

-

prothrombin time

- RXR:

-

retinoid X receptor

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

References

Ge Y, Rikihisa Y. Subversion of host cell signaling by Orientia tsutsugamushi. Microbes Infect. 2011;13(7):638–48.

Peter JV, Sudarsan TI, Prakash JA, Varghese GM. Severe scrub typhus infection: clinical features, diagnostic challenges and management. World J Crit Care Med. 2015;4(3):244–50.

Thipmontree W, Tantibhedhyangkul W, Silpasakorn S, Wongsawat E, Waywa D, Suputtamongkol Y. Scrub typhus in Northeastern Thailand: eschar distribution, abnormal electrocardiographic findings, and predictors of fatal outcome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(4):769–73.

McCrumb FR Jr, Stockard JL, Robinson CR, Turner LH, Levis DG, Maisey CW, Kelleher MF, Gleiser CA, Smadel JE. Leptospirosis in Malaya. I. Sporadic cases among military and civilian personnel. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1957;6(2):238–56.

Seong SY, Choi MS, Kim IS. Orientia tsutsugamushi infection: overview and immune responses. Microbes Infect. 2001;3(1):11–21.

Oaks SCJ, Ridgway RL, Shirai A, Twartz JC. Scrub typhus: Bulletin No 21 United States Army Medical Research Unit. In: Institute for Medical Research, Malaysia. 1983. p. 1–107.

Watt G, Parola P. Scrub typhus and tropical rickettsioses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16(5):429–36.

Kawamura A Jr, Tanaka H. Rickettsiosis in Japan. Jpn J Exp Med. 1988;58(4):169–84.

Anderson NL, Anderson NG. Proteome and proteomics: new technologies, new concepts, and new words. Electrophoresis. 1998;19(11):1853–61.

Blackstock WP, Weir MP. Proteomics: quantitative and physical mapping of cellular proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17(3):121–7.

Alterovitz G, Xiang M, Liu J, Chang A, Ramoni MF. System-wide peripheral biomarker discovery using information theory. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2008;2008:231–42.

Cho NH, Kim HR, Lee JH, Kim SY, Kim J, Cha S, Kim SY, Darby AC, Fuxelius HH, Yin J, et al. The Orientia tsutsugamushi genome reveals massive proliferation of conjugative type IV secretion system and host-cell interaction genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7981–6.

Chao CC, Garland DL, Dasch GA, Ching WM. Comparative proteomic analysis of antibiotic-sensitive and insensitive isolates of Orientia tsutsugamushi. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1166:27–37.

Ogawa M, Shinkai-Ouchi F, Matsutani M, Uchiyama T, Hagiwara K, Hanada K, Kurane I, Kishimoto T. Shotgun proteomics of Orientia tsutsugamushi. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(Suppl 2):239–40.

Cho BA, Cho NH, Min CK, Kim SY, Yang JS, Lee JR, Jung JW, Lee WC, Kim K, Lee MK, et al. Global gene expression profile of Orientia tsutsugamushi. Proteomics. 2010;10(8):1699–715.

Koh GC, Maude RJ, Paris DH, Newton PN, Blacksell SD. Diagnosis of scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(3):368–70.

Luce-Fedrow A, Mullins K, Kostik AP, St John HK, Jiang J, Richards AL. Strategies for detecting rickettsiae and diagnosing rickettsial diseases. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(4):537–64.

Yun SH, Park GW, Kim JY, Kwon SO, Choi CW, Leem SH, Kwon KH, Yoo JS, Lee C, Kim S, et al. Proteomic characterization of the Pseudomonas putida KT2440 global response to a monocyclic aromatic compound by iTRAQ analysis and 1DE-MudPIT. J Proteomics. 2011;74(5):620–8.

Ishihama Y, Oda Y, Tabata T, Sato T, Nagasu T, Rappsilber J, Mann M. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4(9):1265–72.

Janardhanan J, Trowbridge P, Varghese GM. Diagnosis of scrub typhus. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12(12):1533–40.

Xu X, Sun B. Platelet granule secretion mechanisms: are they modified in sepsis? Thromb Res. 2015;136(5):845–50.

Essien EM, Emagha UT. Blood platelet: a review of its characteristics and function in acute malaria infection. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2014;43(4):287–94.

Lee HJ, Park CY, Park SG, Yoon NR, Kim DM, Chung CH. Activation of the coagulation cascade in patients with scrub typhus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;89(1):1–6.

Paris DH, Chansamouth V, Nawtaisong P, Lowenberg EC, Phetsouvanh R, Blacksell SD, Lee SJ, Dondorp AM, van der Poll T, Newton PN, et al. Coagulation and inflammation in scrub typhus and murine typhus–a prospective comparative study from Laos. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(12):1221–8.

Ono Y, Ikegami Y, Tasaki K, Abe M, Tase C. Case of scrub typhus complicated by severe disseminated intravascular coagulation and death. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24(5):577–80.

Schrodl W, Buchler R, Wendler S, Reinhold P, Muckova P, Reindl J, Rhode H. Acute phase proteins as promising biomarkers: perspectives and limitations for human and veterinary medicine. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2016;10(11):1077–92.

Shokal U, Eleftherianos I. Evolution and function of thioester-containing proteins and the complement system in the innate immune response. Front Immunol. 2017;8:759.

Asano M, Komiyama K. Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor. J Oral Sci. 2011;53(2):147–56.

Sorman A, Zhang L, Ding Z, Heyman B. How antibodies use complement to regulate antibody responses. Mol Immunol. 2014;61(2):79–88.

Authors’ contributions

ECP, SYL, and SIK designed and wrote manuscript. CWC and SHY conducted proteomic analysis. HL conducted data analysis. HSS, SJ, and GHK helped in data analysis. CSL collected clinical samples and helped in manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Yeong-Seon Lee at Korea National Institute of Health for providing O. tsutsugamushi genomic DNA and her advice on this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article. Total list of identified proteins has been uploaded as additional files.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board of Chonbuk National University Hospital (IRB Number; CUH 2016-04-007) and all patients provided informed consent.

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Health Technology R&D Project (HI16C0950) through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) grant by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. CRC-16-01-KRICT), and the Korea Basic Science Institute research program (D38402).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure 1.

Nested PCR of 56 kDa gene confirmed the infection of O. tsutsugamushi in scrub typhus patients. Figure 2. Functional annotation of the proteins identified in each group.

Additional file 2: Table 1.

Total list of identified proteins.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, E.C., Lee, SY., Yun, S.H. et al. Clinical proteomic analysis of scrub typhus infection. Clin Proteom 15, 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-018-9181-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12014-018-9181-5