Abstract

Due to its large electric dipole moment, the Rydberg atom exhibits a strong response to weak electric fields, hence it is regarded as a highly promising atomic antenna. However, to enhance the reception sensitivity, split-ring resonators are needed normally, which will brings sensing blind spots. Thus it is not conducive to the application of full-coverage space communication. Here we propose that an atomic antenna with an asymmetric parallel-plate resonator, can not only enhance the received signal, but also eliminate sensing blind spots (pattern roundness can reach 7.8 dB while the split-ring resonator can be up to 39 dB). We analyze the influence of structural parameters on the field enhancement factor and directionality, and further discuss the limitation of the sensitivity by using thermal resistor noise theory. This work is expected to pave the way for the development of field-enhanced Rydberg atomic antennas that communicate without a blind spot.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Rydberg atomic antennas are devices that measure physical quantities utilizing the quantum properties of microscopic particles [1–5], offering great advantages in high sensitivity, small system size, and concealed anti-damage detection [3, 6, 7]. Particularly, it has been theoretically demonstrated that the electric field measurement sensitivity limit is −220 dBm/Hz [8], which is far exceeding the classical receiver sensitivity limit of −174 dBm/Hz. Generally, there are two approaches to improve sensitivity in microwave domain [9], superheterodyne [10–12] and resonator [13–19]. Field-enhanced Rydberg atomic antennas are loading resonators for atomic antennas. However, the directionality of field-enhanced atomic antennas is a great important parameter, which has not been investigated in previous researches, especially for sensing blind spots.

Atomic antennas with isotropic response [6] are needed in many situations, such as wide-beam scanning [20], aerospace communications [21], and precision measurement calibration of electromagnetic fields [22]. Nevertheless, field-enhanced atomic antennas [13–17] will cause reception blind spots at particular angles. In addition, previous literatures [13–17] rely only on Finite Difference Time Domain (FDTD) simulation for sweeping parameter optimization and lack the theoretical methods.

In this paper, we propose a useful approach by adding asymmetry structure, which breaks the rotational symmetry so that the pattern roundness of the asymmetrical parallel-plate resonator (PPR) can be reduced to 7.8 dB comparing with symmetrical resonator [13] of 46.7 dB and symmetrical split-ring resonator (SRR) [16] of 39 dB. Furthermore, we theoretically and experimentally explain the electric field-enhanced behaviors of PPR, including resonant frequency and electric field using rigorous Maxwell’s equation theory. The theoretical electric field enhancement limit of PPR by resistor thermal noise is investigated. The presented theory lets us to complete the PPR design quickly and better comprehend the varying rules of the electric field strength.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, a general theoretical analysis of PPR is presented, experimental implementation is introduced in Sect. 3, and results are discussed in Sect. 4. The formula of resonance frequency and characteristic impedance are in Appendix A and the potential Φ derivation is in Appendix B. Furthermore, transient forming processes, contribution of the electric field, and effect of the cell are investigated in Appendix C. Superheterodyne sensitivity of field-enhanced atomic antenna is investigated in Appendix D.

2 Theory

The most significant difference between the conventional antenna and the field-enhanced atomic antenna is that the gain of the former with isotropic response to linearly polarized radio waves is typically low, such as 2.1 dB for a half-wave dipole, whereas the receive-gain [23] of the latter loading PPR can be at least 20 dB. The traditional antenna directionality coefficient and gain are both restricted by each other. Conventional antennas for high gain must be grouped in an array to expand the receiving area. Conventional antennas operate by receiving power density, but atomic antennas work by sensing electric field strength. Here, the gain of the conventional antenna is relative to the external noise and the receive-gain of the atomic antenna is relative to the internal noise of the receiver. Field-enhanced atomic antennas can operate at a certain frequency by modifying the length of the plate physically or electrically, including the variable capacitance diode. In the design of microwave aperture, some control is needed, such as metasurface [24, 25] control of electromagnetic wave, resonant cavity.

2.1 Estimation of resonance frequency and characteristic impedance

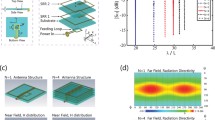

Figure 1(a) depicts the PPR structure. Since the PPR exhibits the same electromagnetic characteristics as a resonant LC circuit, the resonant frequency can be calculated by an equivalent circuit model with a set of parameter values as shown in Fig. 1(b). The capacitance of the equivalent circuit model consists of the gap capacitance \(C_{\mathrm{gap}}\) and the surface capacitance \(C_{\mathrm{surf}}\) due to the excess charge, current, and radiation energy. In addition, the PPR has a flowing current with magnetic field surrounding it, indicating the presence of magnetic flux and parallel inductance L. When the incident field is set to a Gaussian pulse, the resonant frequency of the main mode is obtained. Then, to analyze transient forming processes of electric field, the input field is set a single-frequency continuous plane wave. The duration time exceeds the relaxation time (Appendix C). The frequency of the plane wave is equal to the resonant frequency of the structure.

(a) Atomic-vapor cell is placed inside the PPR. The geometrical details are presented by its specific geometry parameters which is \(l_{\mathrm{up}} = l_{\mathrm{down}} =l_{\mathrm{r}}= 19.2\) mm in length, \(d = 0.01\) mm in thickness, \(h = 10\text{ mm}\) in width, \(g = 4\text{ mm}\), \(w_{\mathrm{r}} = 10\text{ mm}\) in height, and \(w_{\mathrm{up}} =w_{\mathrm{down}}= 3\text{ mm}\) in length. (b) Equivalent lumped LC circuit representation. (c) Contribution of the electric field E along the curve ABCD corresponding to curvilinear coordinate along half PPR with AB = 3 mm, BC = 19.2 mm, CD = 5 mm. Theoretical results corresponding to red dashed line, FDTD simulations corresponding to black line.(d-f) \(x_{\mathrm{r}}\)O\(y_{ \mathrm{r}}\), \(x_{\mathrm{r}}\)O\(z_{\mathrm{r}}\), \(z_{\mathrm{r}}\)O\(y_{ \mathrm{r}}\) E-field strength distribution, respectively

We solve \(C_{\mathrm{gap}} = 0.15\) pF, \(C_{\mathrm{surf}} = 0.23\) pF, L = 11.8 nH, resonant frequency \(f_{1} = 2.35\) GHz (FDTD simulated resonant frequency \(f_{2} = 2.43\) GHz) and characteristic impedance \(Z_{0} = 227 \Omega \) numerically in Appendix A. The FDTD simulated resonant frequency is explained by this theory. Moreover, characteristic impedance of PPR is less than free space wave impedance, which is 377 Ω. This implies that there are reflections of impedance mismatch.

2.2 Estimation of electric field at selected position

An atomic-vapor cell is installed near the open port. There is non-zero current due to electric and magnetic excitations. The gap voltage is defined as [26, 27]

where \(Z_{0}\) is characteristic impedance, Q is quality factor, P is power harvesting. When PPR harvests plane wave energy P is defined

where E is electric field, H is magnetic field, S is Poynting vector, Se is effective aperture, β is the angle between S and Se, which represents the fact that PPR has directionality.

The potential Φ and electric field E in an PPR has been found analytically by assuming that the voltage \(V_{\mathrm{gap}}\) applied to its gap. The simplified expression of the potential Φ in the rectangular boundary coordinate(Appendix B for the derivation) can be represented as

where cn is a Jacobi elliptic function, \(Ke=\int _{0}^{\pi /2}{dt}/{\sqrt{1-1/2\sin ^{2}t}}\), \(z= x_{r}+y_{r}\mathrm{i}\), \(z'=x'+y'\mathrm{i}\), \(\operatorname{Re}[\operatorname{cn}(x'+y'\mathrm{i})]\), \(\operatorname{Im}[\operatorname{cn}(x'+y'\mathrm{i})]\) can be calculated by the formulas [28, 29]. Based on \(\mathbf{E}=-\triangledown \Phi \) equation, \(\mathbf{J}=\sigma \mathbf{E}\) constitutive relation and rigorous Maxwell’s equation theory [30] Eq. (5), electric field E, current density J and charge density ρ can be theoretically analysed, which will help us to calculate the surface capacitance \(C_{\mathrm{surf}}\) in Eq. (14).

where ε is the relative dielectric constant.

To validate the effectiveness of the expression above, the electric field contribution along the curve ABCD corresponding to curvilinear coordinate along half PPR was considered. Theoretical results are compared with the FDTD results derived from a single frequency plane wave with an amplitude of 1 V/m, as depicted in Fig. 1(c). The observed trend in the FDTD simulation closely aligns with the theoretical predictions. According to the theory, the electric field at the probe site indicated by the red dot in Fig. 1(a) is measured to be 14.7 V/m. As depicted in Fig. 1(d–f), \(x_{\mathrm{r}}\)O\(y_{\mathrm{r}}\), \(x_{\mathrm{r}}\)O\(z_{\mathrm{r}}\), \(z_{\mathrm{r}}\)O\(y_{\mathrm{r}}\) E-field strength distribution is presented, respectively.

2.3 Reception pattern investigation

As depicted in Fig. 2(a) with the black dashed line, the implementation of a SRR [13] is employed to enhance the sensitivity of reception. Nevertheless, this approach gives rise to sensing blind spots at \(\varphi =0^{\circ}\), \(\theta =0^{\circ}\), 180°, thereby destroying the isotropic response of Rydberg atoms. The probe reception directivity pattern has been investigated in prior research [31], which theoretically permits an ideal isotropic response to a linearly polarized field to be measured [6]. Figure 2(d) depicts an illustration of the reception pattern measurement setup. We use the definitions of the polar angles θ and azimuth angle φ in spherical coordinate system that θ is the angle with respect to \(z_{r}\)-axis and φ is the counter-clockwise angle of the point of interst projected to \(x_{r}y_{r}\) plane with positive \(x_{r}\)-axis. Simultaneously, the directional dependence of the distribution of electric field enhancement is characterized using measurements of the electric field reception pattern. The optical and electromagnetic wave by the MW horn are linearly polarized along the \(z_{r}\) axis. For the horn antenna, the field propagation is in \(y_{r}\)-direction. Then, the direction of the electric field is along z-direction and magnetic field vector points along \(-\vec{x_{r}}\). The antenna gain at 2.1 GHz is 7.7 dB. The antenna’s H-plane −3 dB beamwidth is 70.2° and the E-plane is 75.4°. VSWR of the antenna ⩽ 3.

The normalized receive-gain directivity patterns in EastWave FDTD of PPR1-PPR4 for manipulations the structure asymmetry comparing with SRR. Reception field pattern for PPR1-PPR4 structure comparing with SRR where (a) \(\varphi = 0^{\circ}\) and θ scanning, (b) \(\theta = 90^{\circ}\) azimuth angle φ scanning and (c) \(\varphi = 90^{\circ}\) polar angle θ scanning. (d) Schematic of the PPR electric field reception pattern measurement setup (top) and the definitions of the polar angles θ and azimuth angle φ in spherical coordinate system that θ is the angle with respect to \(z_{r}\)-axis and φ is the counter-clockwise angle of the point of interst projected to \(x_{r}y_{r}\) plane with positive \(x_{r}\)-axis. The electric field polarization points along z⃗, magnetic field vector points along −x⃗ and the linear optical polarizations inside the cell along z⃗. PPR is placed at an initial position \((x_{r},y_{r},z_{r})=(0,0,0)\). (e) Schematic diagram of PPR1-4

The manipulation of electric and magnetic excitation enables the control of the reception pattern. Long-distance propagation of electromagnetic waves is essentially plane wave. The generation of an induced current is contingent upon the presence of an electric field component that is aligned parallel to the metal plate. This particular type of excitation is commonly referred to as an electric excitation. Induced currents can also be generated through magnetic resonance, in accordance with Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. The receiving field pattern depicted in Fig. 2(b,c) is a result of both electric and magnetic excitation, whereas Fig. 2(a) is only attributed to electric excitation. In Fig. 2(a), the induced current I of the symmetrical resonator structure is expressed by

where \(I_{\mathrm{m}}\) is maximum value of current. Here we define the normalized receive-gain (\(G_{\mathrm{norm}}\)) of atomic antenna in decibels as

As depicted in Fig. 2(a), when the angle θ is set to 0°, it is observed that the potential difference between the top and bottom plates of the asymmetric structure is unequal. Consequently, this asymmetry leads to the generation of effective electric excitation. The presence of an asymmetric structure eliminates the blind spots (reception zero point) in field-enhanced Rydberg atomic antenna sensing.

2.4 Limitation sensitivity of PPR

To thoroughly understand the cost of introducing a metal PPR structure to the atomic antennas, resistor thermal noise analysis is investigated. The Nyquist equation [32] can be utilized to show the thermal noise power spectrum \(S(f)\) (\(\text{V}^{2}/\text{Hz}\)) since the resonant cavity is a conductor and electrons flow about in it, which is a typical dissipative device,

where k is Boltzmann constant, R is the resistor value, T is the physical temperature, \(\rho _{0}\) is electrical resistivity, \(d_{0}=1/\sqrt{\pi f\mu _{0} \sigma }\) is electromagnetic skin depth and σ is electrical conductivity.

Consequently, PPR resistor thermal noise analysis is proportional to physical temperature and resistor value. Thermal noise in resistors exists independently of the existence of voltage or current in the conductor. Furthermore, we offer the noise voltage \(V_{n}=\sqrt{4\mathrm{k}TR}\) and the PPR size depicted in Fig. 1, which exhibits a resistor thermal noise level of −174.32 dBm/Hz. This finding indicates that the sensitivity of the field-enhanced atomic antenna is constrained by the thermal noise limit of the associated resistor, hence establishing the maximum achievable sensitivity.

3 Experimental implementation

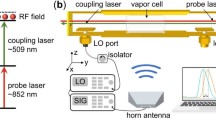

The overall implementation for these experiments is illustrated in Fig. 3. Inset depicts Rydberg states of cesium atoms inside vapor cells are probed by a two-photon Rydberg electromagnetically induced transparency(EIT) ladder scheme. There are two laser sources, at 852 nm with a \(1/e^{2}\) beam diameter of 800 μm, 8 μW power and approximately 510 nm with beam diameter of 1.4 mm, 12 mW power for EIT interrogation of Rydberg states. The 852-nm laser is locked to the one of the \(6S_{1/2}\rightarrow 6P_{3/2}\) transitions with Rabi frequency \(\Omega _{p}\). The 510-nm laser is locked to the \(6P_{3/2}\) → \(50S_{1/2}\) transitions with Rabi frequency \(\Omega _{c}\).

(a)Energy level diagram. (b)Overview of the experimental setup. We have also used the following notations: local oscillator(LO), signal source(SIG). (c) Compact-size portable field-enhanced atomic antenna prototype. Rydberg probe and a dual wavelength integrated laser system together composing the atomic antenna. (d)Three-port fiber-integrated vapor cell Rydberg probe

Smaller size compact-size portable measurement system is unitized compared with previous literature [31, 33–35], which comprises a dual wavelength integrated laser system and a Rydberg fiber-integrated probe as shown in Fig. 3. The dual wavelength integrated laser system, operating at 509 nm and 852 nm, relies on the narrow linewidth properties exhibited by fiber lasers. 509 nm laser is achieved by the process of frequency doubling using Periodically Poled Lithium Niobate crystals. Simultaneous entry of a fraction of the stabilised 852 nm laser and a part of the 509 nm laser occurs within the EIT optical path module. The remaining fractions of both lasers serve as the primary output. The resultant EIT spectrum can be utilized to precisely control and lock the wavelength of the laser at 509 nm. In addition, the Verilog software interface offers functionalities such as probe and coupling frequency locking control, as well as spectrum waveform display. A comparison of portable atomic antennas is presented in Table 1, which summarizes the specific performance comparison with Rydberg fiber-integrated probes [31, 33–35] where volume dimensions and probe efficiency are presented. The efficiency of this probe is transmission efficiency, defined as the ratio of power from output fiber of the 852 nm laser to the probe input to output power after passing through gas chamber. Note that there is no coupled optical input at this point and no electromagnetically induced transparency occurs. For this work, the volume dimensions are significantly reduced compared with previous atomic antennas [31, 33], under optimal Rydberg probe efficiency. It is crucial for practical applications.

The experimental scene in the microwave anechoic chamber is formed by the wave-absorbing material and metal shielding body. Conducting tests on antenna, radar, and other wireless communication devices, as well as electronic products, within a microwave anechoic chamber offers the advantage of minimizing clutter interference. This, in turn, enhances the accuracy and efficiency of the testing process for the equipment being evaluated.

4 Results

In our work described in this paper, there are three major experimental tasks: (i) verify the resonator electric-field-enhancement factor and electric-field polarization response by rotating the antenna, (ii) investigate the field-enhanced atomic antenna reception pattern, (iii) characterize superheterodyne sensitivity(Appendix D).

4.1 Electric-field-enhancement factor and electric-field polarization response

In the off-resonant region, the Rydberg atomic energy level undergoes AC Stark shifts in response to an applied microwave electric field. The electric field strength E and the spectral shift \(\Delta _{l}\) follow quadratic correspondence [36]:

where \(\alpha _{0}(\omega _{RF})\) is called as the dynamic scalar polarizability in the SI units of \(\text{MHz}/(\text{V}/\text{m})^{2}\). We utilize cesium \(50S_{1/2}\) \(m_{j} = 1/2\) state EIT to detect about 2 GHz microwave field. Because \(\alpha _{0}(\omega _{RF})\) polarizability only factor to effect the electric field in the far off-resonant of the Stark shift regime, we have not used 50D state EIT [37], where different \(m_{j} = 1/2\), 3/2, 5/2 have different polarizability [38]. We use a numerical Floquet theory [39] to calculate the \(|50S_{1/2}\rangle \) Rydberg \(\alpha _{0} = 53.7\text{ MHz}\cdot \text{cm}^{2}/\text{V}^{2}\) by fitting a quadratic relationship of the AC shift of the \(50S_{1/2}\) level at an microwave frequency of 2 GHz as shown in Fig. 4(a). During the calculation, the Floquet program calls the ARC [40] calculator package to calculate atomic parameters. The percentage error Δf between the predicted 2.1 GHz and the actual measured data is 5% by the following formula:

where \(f_{\mathrm{Simulation}}\) is FDTD simulated resonant frequency 2.1 GHz (Appendix C Fig. 7(a)), \(f_{\mathrm{Measure}}\) is measured resonant frequency 2 GHz.

(a) Rydberg state \(|50S_{1/2}\rangle \) AC Stark shift \(\Delta _{l}\) fitted to electric field. (b)Measured enhancement factor versus microwave field frequency. (c)EIT spectra of the Rydberg state \(|50S_{1/2}\rangle \) acquired without microwave field (black curve), with an applied 2 GHz 0.5 dBm microwave field and resonator (red curve) and with an applied 2 GHz 25 dBm microwave field (blue curve). The figure shows red and blue curve have same AC shift \(\Delta _{l}\) of about 4.24 MHz. (d)Normalized electric-field polarization response by rotating the antenna, the error bars representing the standard deviation

The properties of measured enhancement factor frequency response are thoroughly explored to elucidate the resonant frequency. Figure 4(b) shows the evolutions of enhancement factor with the increment of microwave frequency where dots correspond to experimental results. It indicates that the resonator has a maximum measured E-field enhancement factor at 2 GHz and has a fairly narrow frequency response. The observed decline in the experimental quality factor Q = 17 compared to the numerical curve Q = 20 (as shown in Appendix C Table 3), as well as the frequency shift from 2.1 GHz to 2 GHz, can be ascribed to the following factors: first, the cell inner surface has nonzero conductivity due to the adsorption of alkali-metal atoms [41] electric-field-screening effect; Second, the resonator metallic losses and minor differences in manufacturing dimensions may also lead to a reduction in the quality factor.

Figure 4(c) shows EIT spectra of the Rydberg state \(|50S_{1/2}\rangle \) without (black curve) and with incident microwave fields when the signal source feeds a signal of 2 GHz, 25 dBm corresponding to the blue curve and 0.5 dBm with resonator corresponding to the red curve. Note that applied microwave field at 2 GHz induces a red-shift and the red and the blue curves have the same AC shift \(\Delta _{l}\) about 4.24 MHz (corresponding to the same detectable E-field strength) can be obtained by attenuating to 24.5 dBm after loading the resonator. Thus, the resonator provides electric-field enhancement factor of 17 (\(10^{(24.5/20)}=17\)). The experimental results indicate that the electric field at the same probe location is measured to be 17 V/m. For the same test method, the resonant frequencies of PPR3, PPR4 are 2.02 GHz and 2.06 GHz, respectively, with electric-field enhancements of 23 dB and 21.5 dB.

Figure 4(d) illustrates the normalized experiment and numerical results when the E-field is rotated from z-polarization (\(\kappa = 0^{\circ}\)) to y-polarization (\(\kappa = 90^{\circ}\)). The slight discrepancy between these results could be attributed to imprecision of the antenna’s rotation, where black dots correspond to experimental results, and blue curves correspond to fitting line.

4.2 Field-enhanced atomic antenna reception pattern

Figure 5 demonstrates measured and FDTD simulated normalized receive-gain pattern response of the symmetrical and asymmetrical PPR. Antenna pattern roundness is defined as the deviation between the maximum and minimum level value from the mean value in a horizontal plane directional pattern. Figure 5(a) shows that the proposed asymmetrical PPR4 breaks the rotational symmetry so that the roundness of the PPR4 is reduced to 7.8 dB from symmetrical PPR1 21.5 dB and symmetrical SRR 39 dB. Figure 5(b,c) shows that PPR1,3,4 appear isotropic when azimuth angle φ and polar angle θ scanning.

Measured and FDTD simulated normalized receive-gain pattern response of the symmetrical and asymmetrical PPR. Reception field pattern for PPR1,3,4 where (a) \(\varphi = 0^{\circ}\) and θ scanning, (b) \(\theta = 90^{\circ}\) azimuth angle φ scanning and (c) \(\varphi = 90^{\circ}\) polar angle θ scanning. The black dots are experimental data and the solid lines are FDTD simulation data

To illustrate the advantage and novelty of this work, Table 2 summarizes the specific performance comparison with pattern roundness, resonant frequency f and enhancement factor F. Given the absence of prior investigations [13, 14, 16, 17] into the directionality of the field-enhanced Rydberg atomic antennas, we conducted an analysis of the pattern roundness based on FDTD simulations utilizing the structural parameters from the previous literature. Compared with the works in References, it is shown that pattern roundness of PPR4 reaches a minimum of 7.8 dB.

5 Conclusion

In summary, we have studied how to eliminate sensing blind spots of field-enhanced Rydberg atomic antenna with asymmetrical PPR structures. Our results have shown that, as the length of the upper edge gradually decreases, the asymmetry from PPR1 to PPR4 gradually increases, with PPR4 having the smallest roundness of 7.8 dB, which is significantly lower compared to the symmetrical SRR structure (39 dB). Importantly, a comprehensive theoretical approach is provided for the electric field-enhanced behaviors of PPR. Finally, we have demonstrated that the theoretical upper limit of electric field enhancement for field-enhance atomic antennas by resistor thermal noise is −174.32 dBm/Hz. In a broader view, our ideas may still be instructive for optimal parameter options to control reception directivity. Thus, our findings demonstrate promising results in the application of full-coverage space communication.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- EIT:

-

Electromagnetically Induced Transparency

- MW:

-

microwave

- SRR:

-

split-ring resonator

- SNR:

-

signal to noise ratio

- LO:

-

local oscillator

- SIG:

-

weak signal

- AT:

-

Autler-Townes

- Cs:

-

cesium

- Ref:

-

reference

- f0:

-

center frequency

- ES:

-

electrical size

- AC:

-

alternating current

References

Facon A, Dietsche E-K, Grosso D, Haroche S, Raimond J-M, Brune M, Gleyzes S. A sensitive electrometer based on a Rydberg atom in a Schrödinger-cat state. Nature. 2016;535(7611):262–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18327.

Gordon JA, Holloway CL, Schwarzkopf A, Anderson DA, Miller S, Thaicharoen N, Raithel G. Millimeter wave detection via autler-townes splitting in rubidium Rydberg atoms. Appl Phys Lett. 2014;105(2). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4890094.

Holloway CL, Gordon JA, Jefferts S, Schwarzkopf A, Anderson DA, Miller SA, Thaicharoen N, Raithel G. Broadband Rydberg atom-based electric-field probe for si-traceable, self-calibrated measurements. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag. 2014;62(12):6169–82. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2014.2360208.

Zhou YL, Yan D, Li W. Rydberg electromagnetically induced transparency and absorption of strontium triplet states in a weak microwave field. Phys Rev A. 2022;105:053714. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.105.053714.

Wu B, Yao J, Wu F, An Q, Fu YQ. Dependence of Rydberg-atom-based sensor performance on different Rydberg atom populations in one atomic-vapor cell. Chin Phys B. 2024;33(2):024205.

Sedlacek JA, Schwettmann A, Kübler H, Löw R, Pfau T, Shaffer JP. Microwave electrometry with Rydberg atoms in a vapour cell using bright atomic resonances. Nat Phys. 2012:819–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2423.

Holloway CL, Simons MT, Gordon JA, Raithel G, Anderson D. Electric field metrology for si traceability: systematic measurement uncertainties in electromagnetically induced transparency in atomic vapor. J Appl Phys 2017;121:233106. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4984201.

Fan H, Kumar S, Sedlacek J, Kübler H, Karimkashi S, Shaffer JP. Atom based rf electric field sensing. J Phys B, At Mol Opt Phys. 2015;48(20):202001. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/48/20/202001.

Santamaria-Botello G, Verploegh S, Bottomley E, Popovic Z. Comparison of noise temperature of Rydberg-atom and electronic microwave receivers. 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.00908. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2209.00908.

Jing M, Hu Y, Ma J, Zhang H, Zhang L, Xiao L, Jia S. Atomic superheterodyne receiver based on microwave-dressed Rydberg spectroscopy. Nat Phys. 2020:911–915.

Simons MT, Haddab AH, Gordon JA, Holloway CL. A Rydberg atom-based mixer: measuring the phase of a radio frequency wave. Appl Phys Lett. 2019;114(11):114101.

Cai M, Xu Z, You S, Liu H. Sensitivity improvement and determination of Rydberg atom-based microwave sensor. Photonics. 2022;9(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics9040250.

Anderson DA, Paradis EG, Raithel G. A vapor-cell atomic sensor for radio-frequency field detection using a polarization-selective field enhancement resonator. Appl Phys Lett. 2018;113:073501. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5038550.

Anderson DA, Raithel GA, Paradis EG, Sapiro RE. Atom-based electromagnetic field sensing element and measurement system.

Wu B, Lin Y, Liao D, Liu Y, An Q, Fu Y. Design of locally enhanced electric field in dielectric loaded rectangular resonator for quantum microwave measurements. Electron Lett. 2022:914–6. https://doi.org/10.1049/ell2.12618.

Holloway CL, Prajapati N, Artusio-Glimpse AB, Berweger S, Simons MT, Kasahara Y, Alu A, Ziolkowski RW. Rydberg atom-based field sensing enhancement using a split-ring resonator. Appl Phys Lett. 2022:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0088532.

Simons MT, Haddab AH, Gordon JA, Novotny D, Holloway CL. Embedding a Rydberg atom-based sensor into an antenna for phase and amplitude detection of radio-frequency fields and modulated signals. IEEE Access. 2019;7:164975–85. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2949017.

Wu B, Lin Y, Chuan WF, Zhang CX, Qiang A, Yi L, Qi FY. Quantum microwave electric field measurement technology based on enhancement electric filed resonator. Acta Phys Sin. 2023;72(3):034204.

Wu B, Liao D, Ding Z, Yang K, Liu Y, An Q, Fu Y. Local oscillator port integrated resonator for Rydberg atom-based electric field measurement enhancement. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2024.

Liu H, Zhang T, Yu D, Fang S, Wang Z. Wide-beam bent cross-shaped dra antenna for wide-angle beam-scanning phased array. Microw Opt Technol Lett. 2023.

Yu L, Wan J, Zhang K, Teng F, Lei L, Liu Y. Spaceborne multibeam phased array antennas for satellite communications. IEEE Aerosp Electron Syst Mag. 2023;38(3):28–47. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAES.2022.3231580.

Hartansky R. Analysis of omni-directivity error of electromagnetic field probe using isotropic antenna. Meas Sci Rev. 2016;16(6):287–93.

Yuan S, Jing M, Zhang H, Zhang L, Xiao L, Jia S. An isotropic antenna based on Rydberg atoms. 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.09023. arXiv preprint, Focus to learn more. arXiv:2309.09023.

Tian T, Huang X, Xu Y, Liu P, Liu C, Hu N, Zhang J, Wu Z. A wideband energy selective surface with quasi-elliptic bandpass response and high-power microwave shielding. IEEE Trans Electromagn Compat. 2024;66(1):224–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2023.3325438.

Kui W, Xianjun H, Tao T, Wentao H, Peiguo L. Design and demonstration of high-power density infrared nonlinear filtering window with em shielding. Opt Express. 2024;32(4):5956–68.

Iza F, Hopwood J. Split-ring resonator microplasma: microwave model, plasma impedance and power efficiency. Plasma Sources Sci Technol. 2005;14(2):397. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-0252/14/2/023.

Dextre RA, Xu KG. Effect of the split-ring resonator width on the microwave microplasma properties. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 2017;45(2):215–22. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2016.2646661.

The real part of Jacobi elliptic function cn. https://functions.wolfram.com/EllipticFunctions/JacobiCN/19/01/.

The imaginary part of Jacobi elliptic function cn. https://functions.wolfram.com/EllipticFunctions/JacobiCN/19/02/.

Guru BS, Hiziroglu HR. Electromagnetic field theory fundamentals. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Anderson DA, Sapiro RE, Raithel G. A self-calibrated si-traceable Rydberg atom-based radio frequency electric field probe and measurement instrument. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag. 2021;69(9):5931–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2021.3060540.

group, S.C. Resistors thermal noise. Silicon Chip. 2015;75.

Simons MT, Gordon JA, Holloway CL. Fiber-coupled vapor cell for a portable Rydberg atom-based radio frequency electric field sensor. Appl Opt. 2018;57(22):6456–60. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.57.006456.

Mao R, Lin Y, Yang K, An Q, Fu Y. A high-efficiency fiber-coupled Rydberg-atom integrated probe and its imaging applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel Propag Lett. 2023;22(2):352–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/LAWP.2022.3212057.

Yi L, Feng-Chuan W, Rui-Qi M, Jia-Wei Y, Yi L, Qiang A, Yun-Qi F. Development of three-port fiber-coupled vapor cell probe and its application in microwave digital communication. Acta Phys Sin. 2022;170702. https://doi.org/10.7498/aps.71.20220594.

Cardman R, Gonçalves LF, Sapiro RE, Raithel G, Anderson DA. Atomic 2d electric field imaging of a Yagi–Uda antenna near-field using a portable Rydberg-atom probe and measurement instrument. Adv Opt Technol. 2020;9(5):305–12. https://doi.org/10.1515/aot-2020-0029.

Yang K, Mao R, He L, Yao J, Li J, Sun Z, Fu Y. Local oscillator port embedded field enhancement resonator for Rydberg atomic heterodyne technique. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-023-00179-w.

Hu J, Li H, Song R, Bai J, Jiao Y, Zhao J, Jia S. Continuously tunable radio frequency electrometry with Rydberg atoms. Appl Phys Lett. 2022;121(1). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0086357.

Jiao Y, Hao L, Han X, Bai S, Raithel G, Zhao J, Jia S. Atom-based radio-frequency field calibration and polarization measurement using cesium n d j Floquet states. Phys Rev Appl. 2017;8(1):014028. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.8.014028.

Šibalić N, Pritchard JD, Adams CS, Weatherill KJ. Arc an open-source library for calculating properties of alkali Rydberg atoms. Comput Phys Commun. 2017;220:319–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2017.06.015.

Jau YY, Carter T. Vapor-cell-based atomic electrometry for detection frequencies below 1 kHz. Phys Rev Appl. 2020;13:054034. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.13.054034.

Shatz LF, Christensen CW. Numerical inductance calculations based on first principles. PLoS ONE. 2014:111643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111643.

Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Berliner LJ. Biomedical EPR, Part B: methodology, instrumentation, and dynamics. 24. Berlin: Springer Science Business Media; 2004.

Vallecchi A, Shamonina E, Stevens CJ. Analytical model of the fundamental mode of 3d square split ring resonators. J Appl Phys. 2019;014901. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5053482.

Allen J, Segre S. The electric field in single-turn and multi-sector coils. Nuovo Cimento (1955-1965). 1961;21(6):980–7.

Schubert AB. Conformal mapping of a circle onto a rectangle. 1968. https://doi.org/10.2172/4800477. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/4800477.

Fong C. Elliptification of rectangular imagery. Electrical Engineering and Systems Science. 2017.

Zhou YL, Yu XD, Wu CW, Li XQ, Zhang J, Li WB, Chen PX. Accelerating relaxation through liouvillian exceptional point. Phys Rev Res. 2023;5(9):043036. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.5.043036.

Guo Y. Influence of transient physical processes in resonant cavities on the pulse edge of a klystron. PhD thesis. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences; 2009.

Meyer DH, Kunz PD, Cox KC. Waveguide-coupled Rydberg spectrum analyzer from 0 to 20 GHz. Phys Rev Appl. 2021;15:014053. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.014053.

Ripka F, Amarloo H, Erskine J, Liu C, Ramirez-Serrano J, Keaveney J, Gillet G, Kübler H, Shaffer JP. Application-driven problems in Rydberg atom electrometry. In: Optical and quantum sensing and precision metrology. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2586718.

Fan H, Kumar S, Sheng J, Shaffer JP, Holloway CL, Gordon JA. Effect of vapor-cell geometry on Rydberg-atom-based measurements of radio-frequency electric fields. Phys Rev Appl. 2015;4:044015. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.4.044015.

Robinson AK, Artusio-Glimpse AB, Simons MT, Holloway CL. Atomic spectra in a six-level scheme for electromagnetically induced transparency and autler-townes splitting in Rydberg atoms. Phys Rev A. 2021;103:023704. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.103.023704.

Holloway CL, Simons MT, Gordon JA, Wilson PF, Cooke CM, Anderson DA, Raithel G. Atom-based rf electric field metrology: from self-calibrated measurements to subwavelength and near-field imaging. IEEE Trans Electromagn Compat. 2017;59(2):717–28. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMC.2016.2644616.

Funding

We are thankful for insightful discussions with Mingyong Jing. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12104509, 62105338, 12074433) and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (Grants No. 2023JJ30626).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bo Wu and Yun-qi Fu constructed the theoretical scheme; Bo Wu wrote the main manuscript text; Yanli Zhou, Zhen-ke Ding, Ruiqi Mao, Sixian Qian, Zhiqian Wan, Yi Liu, Yi Lin, and Qiang An gave some important suggestions about the calculation methods; and Yun-qi Fu made the final revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Estimation of resonance frequency and characteristic impedance

Inductance L Eq. (12) [42], capacitance of the gap \(C_{\mathrm{gap}}\) Eq. (13) [43], surface capacitance \(C_{\mathrm{surf}}\) Eq. (14) [44], resonant frequency f and characteristic impedance \(Z_{0}\) for a rectangular loop with a rectangular cross-section can be calculated.

where weighting factor \(p_{e} = 1-g/4l_{r}\), \(\mu _{0}\) is magnetic permitivity, \(\varepsilon _{0}\) is free space permittivity, ρ is the charge density and V is the voltage between two symmetric points on the surface.

Appendix B: Potential Φ derivation

The currently available analytical expression for the potential is for the disc condition, but in our device it is a rectangular, so a transformation is required. The potential Φ in the disc boundary coordinate can be changed to the rectangular boundary coordinate by a coordinate change conformal mapping. The simplified expression of the potential Φ [45] in the disc boundary coordinate can be represented as

Assuming the input disc coordinates are (\(u,v\)), the output square coordinates are (\(x_{s},y_{s}\)), and the output rectangular coordinates are (\(x_{r},y_{r}\)). As shown in Fig. 6, the circle radius r is equal to 1, the square side length \(l_{s}\) is equal to 2, and the rectangle length is \(l_{r}\) and its width is \(w_{r}\).

Based on conformal mapping [46, 47], a square to a disc mapping can be represented as

where cn is a Jacobi elliptic function, \(Ke=\int _{0}^{\pi /2}{dt}/{\sqrt{1-1/2\sin^{2}t}}\). Through square-to-disc mappings, we can extend it to handle rectangle. The rectangular and square coordinates are directly related as follows:

Substituting Eq. (18)(19)(20) back to the Eq. (17)

where \(z= x_{r}+y_{r}\mathrm{i}\), \(z'=x'+y'\mathrm{i}\), \(\operatorname{Re}[\operatorname{cn}(x'+y'\mathrm{i})]\), \(\operatorname{Im}[\operatorname{cn}(x'+y'\mathrm{i})]\) can be calculated by the formulas [28, 29]. These steps are summarized in the Fig. 6. Here, based on the conformal mapping of a circle onto a rectangular, we get the Eq. (21) potential expression of rectangular coordinates.

Appendix C: Transient forming processes, contribution of the electric field, and effect of the cell

Since a resonator needs relaxation time to achieve steady state, it is required that the pulse width of the microwave signal must be greater than the relaxation time [48] to ensure the regular operation. By comparison with and without cell in Fig. 7(a), the resonant frequency experiences a sharp downward trend from without cell to with cell. FDTD simulation with a 1 V/m single-frequency continuous wave excitation source is performed, and numerical curves are obtained, as illustrated in Fig. 7(b). The fitting equation for the transient field E is [49] Eq. (23).

where F is the field enhancement factor, \(\tau _{0}\) (\(\tau _{0}= \mathrm{C}Q/f_{0}\)) is the relaxation time, C is a constant determined by the resonator, \(f_{0}\) is the resonant frequency, Q (\(Q=f_{0}/BW\)) is the quality factor, and BW is the 3 dB bandwidth.

(a)The comparison of E-field versus frequency three curves. Curve 1 \(l_{r} = 24.1\text{ mm}\) without cell(blue dotted line), curve 21 \(l_{r} = 19.2\text{ mm}\) without cell(red dotted line), curve 21 \(l_{r} = 19.2\text{ mm}\) with cell(yellow solid line). (b)Simulated transient response of E field strength. (c) The insert shows a zoom in the transient response. (d-g) The intensity graphs show the measured time dependent out-of-plane electric field E(t) distribution at successive times t = 0.18 ns (d), 0.26 ns (e), 0.48 ns (f), and 0.7 ns (g), respectively

As shown in Fig. 7(b), \(\tau _{0}\) is approximately 4 ns, BW is 90.3 MHz, and Q is 23. Relaxation time is less than the Rydberg atomic decoherence time, which is approximately on the order of microseconds [50]. The theoretical calculation is consistent with the FDTD simulation. In conclusion, from Table 3 we can clearly see the performance comparison of the fitting line parameters on the basis of 2.1 GHz resonant frequency. Table 3 illustrate that the field enhancement factor F decreases from 32 with cell (Curve 3) to 20 without cell (Curve 2), the relaxation time \(\tau _{0}\) falls by 2.1 ns, the 3 dB bandwidth BW rises by 64 MHz, and the quality factor Q is 18 without cell, compared to 30 with cell. Inset Fig. 7(c) illustrates a zoom in the transient response. The time dependent electric field measured at the probe position is shown in (d-g) are marked by black dots. Figure 7(d)–(g) were extracted from a movie showing the full time dependent electric field distribution \(E(Y,Z,t)\). The color scale indicates the calibrated electric field. This helps to better analyse the resonance process to understand the resonance principle. The plane wave propagates from left to right, and the electric field is gradually enhanced at the open-end, after steady state, the electric field around the resonant structure is also enhanced, but remains strongest at the open-end.

Figure 8 illustrates an E-field distribution comparison at resonant frequency between the FDTD simulated a square cross-section vapor cell with solid walls depicted in Fig. 8(b), and without cell depicted in Fig. 8 (a). In the bottom Fig. 8, we present the cumulative histograms (Fig. 8(c)) and histograms of normalized E-field (Fig. 8(d)) generated by sampling a cylinder region of approximately ten million samples. The diameter of the cylinder is 1 mm, which is a reasonable size for both the probe and the coupling beam. The FDTD simulation results clearly demonstrate the differences between the two scenarios, with cell having a significant impact on the E-field homogeneity. To improve the homogeneity within the cell, consider using a vapor cell with perforated walls [51]. Overall, the relative dielectric constant \(\varepsilon _{r}\) of cell wall is not equal to 1, which renders much larger electrical size. Changes in the refractive index n (\(n=\sqrt{\varepsilon _{r}}\)) parameters of the cell walls in FDTD simulations, with and without the cell, can greatly impact the resonant frequency, where \(\varepsilon _{r}\) is relative permittivity. Due to the small size of vapor-cell compared to the wavelength of the E-field, the effects of the vapor cell on the measured rf E-field are not significant [52].

(a)(b)Comparison E-field distribution without and with cell corresponding to Table 3 curve2,3. The figure shows a simulation scenario. (c)Cumulative histogram of the normalized electric field within the beam. (d)Histograms of the normalized electric field

Appendix D: Superheterodyne sensitivity of field-enhanced atomic antenna

In order to investigate the superheterodyne sensitivity that is theoretically defined as the minimum detectable power when the signal to noise ratio decreases to 1, two signal generators are utilized. The LO microwave source frequency is 2 GHz, while the frequency of the weak SIG is 2 GHz + 100 kHz, with a detuned frequency of 100 kHz. The 100 kHz detuned frequency means that once the coupling laser is set, the probe laser intensity will oscillate at a beat-note frequency of 100 kHz. The results indicate that the Rydberg atom can achieve a function similar to a mixer and accurately down-convert the microwave signal according to the frequency of the LO signal. The spectral analyzer has a 1 Hz resolution bandwidth.

Additionally, this emphasizes the importance of taking these potential errors sources into account when performing experiments and simulations to obtain more accurate results. As the resonance-based system is more sensitive to errors, this paper take all the cell walls refractive index and metal reflections into account. The issues of metal reflections, space scattering disturbance can appear multi-reflections inside the cell and standing waves disturbance(or resonances) [2]. The E-field strength in space can be expressed as [53]:

where c is the light speed in vacuum, \(\varepsilon _{0}\) is the permittivity of free space, \(R = 0.05\text{ m}\) is the distance from antenna to the laser beam, \(F_{0}\) is the perturbation factor caused by space scattering and standing wave(or resonances) disturbance in the cell, \(P_{\mathrm{SIG}}G_{\mathrm{T}}L\) is the radiated power of microwave (\(P_{ \mathrm{SIG}}G_{\mathrm{T}}L = P_{\mathrm{SIG}} + G_{\mathrm{T}} - L\), \(P_{\mathrm{SIG}}\) represents the output power of signal source, \(G_{\mathrm{T}} = 11\) dB represents the gain of antenna, \(L = -1.5\) dB represents the insertion loss of transmission line). The parameter \(F_{0}\) which can be determined numerically or experimentally [2, 54] is estimated \(F_{0}\) ≈ 0.411 for 2 GHz according to the electric-field.

As shown in Fig. 9, the beat-note intensity from the spectrum analyzer is a function of signal generator for the cases with resonator in blue curve and without in black curve. As indicated by the two black circles, the two curves are shifted along the x-axis by indicating an enhancement of 24 dB. This work identifies the intersections of the linear response curves and the noise floor of the spectrum analyzer as sensitivity. Ultimately, we find that resonator allows for a sensitivity of 2 \(\mu \text{V}/\text{cm}/\sqrt {\text{Hz}}\), which is 16.7 times of magnitude improvement in sensitivity than without resonator, which allows for 336 \(\mu \text{V}/\text{cm}/\sqrt {\text{Hz}}\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, B., Zhou, YL., Ding, ZK. et al. Eliminating sensing blind spots of field-enhanced Rydberg atomic antenna via an asymmetric parallel-plate resonator. EPJ Quantum Technol. 11, 30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-024-00239-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-024-00239-9