Abstract

We investigate the holographic p-wave superconductors in the presence of the higher order corrections on the gravity as well as on the gauge field side. On the gravity side, we add the Gauss–Bonnet curvature correction terms, while on the gauge field side we take the nonlinear Lagrangian in the form \({\mathcal {F}}+b {\mathcal {F}}^{2}\), where \({\mathcal {F}}\) is the Maxwell Lagrangian and b indicates the strength of the nonlinearity. We employ the shooting method for the numerical calculations in order to obtain the ratio of the critical temperature \(T_{c}\) over \(\rho ^{1/(d-2)}\). We observe that by increasing the values of the mass and the nonlinear parameters the critical temperature decreases and thus the condensation becomes harder to form. In addition, the stronger Gauss–Bonnet parameter \(\alpha \) hinders the superconducting phase in Gauss–Bonnet gravity. Furthermore, we calculate the electrical conductivity based on the holographic setup. The real and imaginary parts are related by the Kramers–Kronig relation, which indicates a delta function and a pole in low frequency regime, respectively. However, at enough large frequencies the trend of the real part can be interpreted by \(Re[\sigma ]=\omega ^{(d-4)}\). Moreover, in holographic model the ratio \(\omega _{g}/T_{c}\) is always much larger than the BCS value 3.5 due to the strong coupling of holographic superconductors. In both kinds of gravity, decreasing the temperature or increasing the effect of nonlinearity shifts the gap frequency toward larger values. Besides, the gap frequency occurred at larger values by enlarging the Gauss–Bonnet parameter. In general, the behavior of the conductivity depends on the choice of the mass, the nonlinear and the Gauss–Bonnet parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the gauge/gravity duality, which connects a weak gravitational system in \((d+1)\) dimensions to the strong coupling conformal field theory in d dimensions, has attracted a lot of attention because it provides a powerful theoretical method to study strong interacting systems such as high temperature superconductors [1,2,3,4,5,6]. One of the famous consequences of the AdS/CFT correspondence is the appearance of a revolutionary theory which is called holographic superconductor theory [2]. The idea of a holographic superconductor was proposed in 2008 [2] by applying the AdS4/CFT3 correspondence on the probe limit in Einstein gravity. Based on this theory in order to describe a superconductor on the boundary, we need a transition from hairy black hole to a no-hair black hole in the bulk for temperatures below and above the critical value, respectively [7]. The appearance of hair corresponds to the spontaneous U(1) symmetry breaking [7]. This theory opened up a new horizon in condensed matter physics to study the high temperature superconductors as well as unconventional types [2, 8]. Furthermore, holographic superconductors have been widely investigated in the presence of nonlinear electrodynamic,s which involves more information than the usual Maxwell state. There are different kinds of nonlinear electrodynamics in the literature, such as Born–Infeld [9], Exponential [10], Logarithmic [11] and Power–Maxwell [12] electrodynamics. Many investigations have been devoted to disclosing analytically and numerically different aspects of holographic superconductors in the presence of various kinds (see e.g. [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]).

Besides the s-wave superconductors, which can be described very well by the BCS theory, there are unconventional superconductors such as p-wave and d-wave superconductors [37, 38]. Unconventional superconductors can be classified as high temperature and strong coupling superconductors. It is expected that the holographic hypothesis may shed some light on this field by introducing holographic p-wave as well as d-wave superconductors. In the past decade, a variety of research has been done to investigate the properties of unconventional superconductors based on the holographic hypothesis (see e.g. [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]). The holographic p-wave superconductors can be interpreted as odd parity or triplet superconductors, which are constructed by coupling of electrons with parallel spins by exchange of the electronic excitations with angular momentum \(\ell = 1\) [38]. The holographic p-wave superconductors have been explored from different points of view, such as condensation of a complex or real charge vector field in the bulk, which corresponds to the vector order parameter in the boundary, or the spin-1 order parameter that may originate from the condensation of a 2-form field on the gravity side [39,40,41,42,43]. Introducing a SU(2) Yang–Mills gauge field in the bulk in which one of the gauge degrees of freedom corresponds to the vector order parameter at the boundary is another method to study this topic. The superconducting phase at the boundary for this type of holographic superconductors corresponds to the appearance of vector hair outside the horizon by decreasing the temperature below the critical value [50].

In this work, we are going to investigate the holographic p-wave superconductors in all higher dimensions by taking into account the higher order corrections both on the gravity and on the gauge field sides. While most previous work on the holographic p-wave superconductors has investigated the presence of the linear Maxwell field, it is interesting to examine the effects of the nonlinear electrodynamics on the properties of holographic p-wave superconductors. For the correction to the gauge field side, we consider the general nonlinear electrodynamics with higher order correction term, namely \({\mathcal {L}}={\mathcal {F}}+b {\mathcal {F}}^{2}\). We shall do the numerical calculations for different values of the mass m and the nonlinear parameter b in each dimension to disclose the effects of these terms on the critical temperature. In all cases, we find the relation between the critical temperature \(T_{c}\) and \(\rho ^{1/(d-2)}\) where \(\rho \) is regarded as the charge density, and we plot the behavior of condensation as a function of the temperature. We shall also explore the electrical conductivity by applying an appropriate perturbation on the gauge field in the background. We obtain the electrical conductivity formula and plot the behavior of the real and imaginary parts of the conductivity as a function of the frequency for different values of the mass and of the nonlinearity parameter in \(d=4,5\) and 6. Not only the trend of the figures differs by dimension but also our choice of mass and nonlinearity has a straightforward effect on the behavior of the conductivity. Besides the obvious differences, all of them show some universal behavior. For example, the Kramers–Kronig relation relates the real and imaginary parts of the conductivity. In the low frequency regime, we observe a delta function behavior for the real part, while the imaginary part has a pole. The infinite DC conductivity is a feature of the superconducting phase. Furthermore, we find the universality \(\omega _{g} \simeq 8 T_{c}\) is totally dominated but deviates in higher dimensions—which is logical. Moreover, the gap frequency depends on the mass and nonlinearity parameters. Afterwards, by following the same procedure as before we do our study in Gauss–Bonnet gravity with higher order corrections in gravity and gauge fields in d-dimensional spacetime. The holographic p-wave superconductor in Gauss–Bonnet gravity was previously studied in [53, 54]. We analyze the vector condensation and find that the critical temperature reduces not only by increasing the mass and nonlinear parameter but also by enlarging the Gauss–Bonnet parameter \(\alpha \). Finally, we consider the electrical conductivity for a holographic p-wave superconductor in Gauss–Bonnet gravity with higher order corrections. The global trends are also seen in this case. In this gravity, the gap frequency depends on the mass, nonlinearity and the Gauss–Bonnet parameters and the ratio of \(\omega _{g}/T_{c}\) deviates from the universal value 8 by increasing the effect of \(\alpha \), too.

This work is in outline as follows. In Sect. 2.1 we introduce the holographic p-wave model in Einstein gravity through condensation of a vector field. In Sect. 2.2, we describe the procedure of calculating electrical conductivity based on the AdS/CFT correspondence. Section 3.1 is devoted to the conductor/superconductor phase transition in a holographic setup in Gauss–Bonnet gravity. We calculate the electrical conductivity in the Gauss–Bonnet gravity with higher order corrections in Sect. 3.2. Finally, we summarize our results in Sect. 4.

2 Holographic p-wave superconductor in Einstein gravity

2.1 The holographic model and condensation of the vector field

We adopt the following form for the action to describe a holographic p-wave superconductor with a vector field \(\rho _{\mu }\) with mass m and charge q:

where g and R are metric determinant and Ricci scalar, respectively, l is the radius of the AdS spacetime, which is related to the negative cosmological constant via

Hereafter, for simplicity we set \(l=1\). The Lagrangian density of nonlinear electrodynamics \({\mathcal {L}}_{{{\mathcal {N}}}{{\mathcal {L}}}}\) in the Lagrangian of the matter field, \({\mathcal {L}}_{m}\), is given by

When the nonlinearity parameter tends to zero, \(b\rightarrow 0\), it reduces to the standard Maxwell Lagrangian, namely \({\mathcal {L}}_{{{\mathcal {N}}}{{\mathcal {L}}}}\rightarrow -1/4 F_{\mu \nu }F^{\mu \nu }\) where \(F_{\mu \nu }=\nabla _{\mu } A_{\nu }-\nabla _{\nu } A_{\mu }\). The term \(b{\mathcal {F}}^{2}\) is the first order leading nonlinear correction term to the Maxwell field. There are several motivations for choosing the nonlinear Lagrangian in the form of (3). First, the series expansion of the three well-known Lagrangian of nonlinear electrodynamics such as Born–Infeld, Logarithmic and Exponential nonlinear electrodynamics have the form of (3) [55]. Second, calculating a one-loop approximation of QED, it was shown [56] that the effective Lagrangian is given by (3). Besides, if one neglect all other gauge fields, one may arrive at the effective quadratic order of U(1) as \({\mathcal {F}}^{2}\) [57, 58]. Furthermore, considering the next order correction terms in the heterotic string effective action one can obtain the \({\mathcal {F}}^{2}\) term as a correction to the bosonic sector of supergravity, which has the same order as the Gauss–Bonnet term [57,58,59].

With the help of the covariant derivative \(D_{\mu }=\nabla _{\mu }- i q A_{\mu }\), we can define \(\rho _{\mu \nu }=D_{\mu } \rho _{\nu }-D_{\nu } \rho _{\mu }\). The last term in the matter Lagrangian can be ignored in our work because it characterizes the strength of the interaction between \(\rho _{\mu }\) and \(A_{\mu }\) with \(\gamma \) as the magnetic moment in the case with an applied magnetic field.

Varying the action (1) with respect to the gauge field \(A_{\mu }\) and the vector field \(\rho _{\mu }\), we obtain the equations of motion as

In order to describe a d-dimensional AdS Schwarzschild black hole with a flat horizon, we consider the metric

where \(r_{+}\) defines the horizon location obeying \(f(r_{+})=0\). Meanwhile, the vector and the gauge fields are assumed to have the following form:

The Hawking temperature of the black hole is given by [36]

Inserting Eqs. (6) and (8) in the field equations (4) and (5), we arrive at

These equations have the asymptotic solutions (\(r\rightarrow \infty \)) of the form

with

where our chosen masses should satisfy the Breitenlohner–Freedman (BF) bound [60],

Based on the AdS/CFT correspondence \(\rho _{x_-}\) and \(\rho _{x_+}\) are, respectively, interpreted as the source and the expectation value \(\langle J_{x}\rangle \), which plays the role of the order parameter in the boundary theory. Moreover, \(\mu \) and \(\rho \) are regarded as chemical potential and charge density in the dual field theory. In order to follow our research, we use the shooting method which solves Eqs. (10) and (11) numerically by applying suitable conditions. For this purpose, we introduce a new variable \(z=r_{+}/r\). For convenience, we will set \(r_{+}=1\) in the following calculation. We do our numerical solutions in \(d=4, 5\) and 6 and find the relation between the critical temperature and \(\rho ^{1/(d-2)}\). We summarize our results in Tables 1, 2 and 3. By analyzing the effects of mass of the vector field, we investigate the properties of the holographic superconductor for two values of mass in each dimension. Meanwhile, we consider the effects of nonlinearity for this model. Our results show that by increasing the value of nonlinearity parameter as well as mass makes the condensation harder to form. Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the behavior of the condensation \(\langle J_{x}\rangle ^{1/(1+\Delta _{+})}\) for two values of mass as a function of the temperature for different values of the nonlinearity parameter in each dimension. According to these graphs, the condensation value goes up for stronger effect of the nonlinearity parameter and mass, which means it is harder to have a superconductor in the presence of nonlinear electrodynamics for massive vector fields. It was already argued that a holographic p-wave superconductor undergoes the first order phase transition [40, 43] in some cases instead of the usual second order type. However, in our work with these choices for the mass and nonlinear parameters, we do not observe this phenomenon. It may occur in the presence of a backreaction parameter or for other values of the mass and nonlinear parameters.

2.2 Electrical conductivity

In this section, we are going to calculate the electrical conductivity as a function of the frequency for this holographic superconductor in the presence of nonlinear electrodynamics. To this aim, we apply an appropriate electromagnetic perturbation as \(\delta A_{y}=A_{y} e^{-i \omega t}\) on the black hole background which, based on the AdS/CFT duality, corresponds to the boundary electrical current. We choose this form of perturbation for simplicity to be the same as [43, 53, 54]. The consequence of turning on this perturbation in gauge field occurs in the y-component of Eq. (4),

which has the asymptotic behavior

by considering \(A^{(0)}\) and \(A^{(1)}\) as constant parameters, we have the following solution for \(A_{y}\) asymptotically:

where \(\Lambda \) is an arbitrary constant. Equations (16) and (17) are the same as the corresponding equations in the s-wave case [27]. According to the AdS/CFT correspondence, the electrical current based on the on-shell bulk action \(S_{o.s}\) and the Lagrangian of the matter field \({\mathcal {L}}_{m}\) is defined by

where

by inserting (17) in (19), we arrive at

Sticking to the AdS/CFT framework, the electrical conductivity is

Therefore, the electrical conductivity, based on the holographic approach by using Eqs. (18), (19) and (21) and adding appropriate counterterms for \(d=5\) and 6 to remove the divergency based on the re-normalization method [61], is

which is in complete agreement with the \(\sigma _{xx}\) obtained in [27]. This shows that the calculation of \(\sigma _{yy}\) in the holographic p-wave superconductor is the same as \(\sigma _{xx}\) in a holographic s-wave superconductor [53]. In order to investigate the trend of the conductivity numerically, we impose the ingoing wave boundary condition near the horizon for \(A_{y}\) as follows:

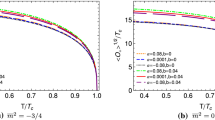

where the Hawking temperature is expressed by T, and \(a, b, \ldots \) are coefficients which can be obtained by Taylor expansion of Eq. (16) around the horizon. Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 illustrate the behavior of the real and imaginary parts of the conductivity as a function of \(\omega /T\) for different values of mass and nonlinearity parameters in different dimensions. In spite of the fact that there are obvious differences in the figures, they show some universal behavior. First of all, the real part of the conductivity is related to the imaginary part, based on the Kramers–Kronig relation, which means the appearance of the delta function and pole in real and imaginary parts of the conductivity, respectively. Secondly, the superconducting gap which appears below the critical temperature becomes deeper and sharper by diminishing the temperature, which causes larger values of \(\omega _{g}\). This fact approved the results of the previous section about condensation by decreasing the temperature, because we can interpret \(\omega _{g}\) as the energy needed to break the fermion pairs. So, the bigger values of \(\omega _{g}\) leads to harder formation of fermion pairs, which hinders the conductor/superconductor phase transition [53]. At large frequencies, the behavior of the conductivity can be indicated to have a power law behavior as \(Re[\sigma ]=\omega ^{(d-4)}\) similar to the s-wave case [27]. In addition, based on the BCS theory \(\omega _{g}\approx 3.5T_{c}\); meanwhile in a holographic setup the ratio of gap frequency over critical temperature is found to be the universal value around 8, which hints to the fact that in BCS theory the pairs couple to each other weakly with no interaction. However, the holographic superconductors are strongly coupled. This strong coupling is the reason that we use a holographic model to describe high temperature superconductors which exist in the strong coupling regime [53]. Due to the details described, we should say that the peak of real part of the conductivity follows the same trend as the minimum value of imaginary part by decreasing the temperature. They shift toward larger frequencies in all dimensions. Our choice of the mass has a direct influence on the behavior of conductivity, which becomes so obvious in some cases. For example, in \(d=5\) we face a sharp peak and a deep minimum in the real and imaginary parts for \(m^{2}=-3/4\), while for the case that the vector field has a mass equal to \(m^{2}=5/4\) we observe a smooth peak and minimum in the two parts of the conductivity. Overall, it seems that \(T=0.3 T_{c}\) has a strong effect on the conductivity in \(d=5\) and 6. In order to study the effect of nonlinear electrodynamics on the conductivity, we plot its behavior in fixed temperature \(T=0.3T_{c}\) in Figs. 10 and 11. According to these graphs, the effects of the nonlinearity parameter on the conductivity straightforwardly depend on the mass and dimension. For example, in \(d=4\) and for \(d=5\) with \(m^{2}=5/4\) increasing the nonlinearity renders the peak and minimum parts more smooth and flat. However, for other cases the system does not behave like that. In \(d=6\), increasing the nonlinearity causes a smaller first gap, enlarging the second one in the real part of the conductivity. In general, the gap frequency is shifted in the presence of nonlinear electrodynamics.

3 Holographic p-wave superconductor in Gauss–Bonnet gravity

3.1 Conductor/superconductor phase transition in holographic setup

In this section, we want to study the condensation of the vector field in the background of the AdS black holes with higher order corrections both in the gravity and gauge field. We write down the action in the following form:

where, for the same parameters as Sect. 2.1, we have a similar definition, while the Gauss–Bonnet parameter, the Ricci tensor and the Riemann curvature tensor are defined, respectively, by \(\alpha \), \(R_{\mu \nu }\) and \(R_{\mu \nu \rho \sigma }\). When \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\), the above action reduces to the Einstein one. We take the line elements of the spacetime metric as

where the function f(r) has the asymptotic behavior

We can present the effective radius \(L_{\text {eff}}\) for the AdS spacetime as [53]

Based on the above equation, we have a well-defined vacuum expectation value \(\alpha \le 1/4\) where the upper bound \(\alpha = 1/4\) is called the Chern–Simon limit [53]. Besides, on the CFT side we consider the causality constraint on our choice of Gauss–Bonnet parameter with \(-7/36\le \alpha \le 9/100\) and \(-51/196\le \alpha \le 32/256\) for AdS5/CFT4 and AdS6/CFT5, respectively [62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. We choose the vector and gauge fields to be the same as Eq. (8). By variation of Eq. (24) with respect to gauge and vector fields, the same equations as Eqs. (4) and (5) are obtained. Moreover, Eqs. (10) and (11) with the asymptotic behavior as (12) are recovered, finally. Equation (13) in Gauss–Bonnet gravity changes to

with the Breitenlohner–Freedman (BF) bound

In the Maxwell limit where \(b\rightarrow 0\), the field equations turn to the corresponding equations in the equation of [53]. In addition, the Hawking temperature equals Eq. (9). The numerical results are listed in Tables 4 and 5. In order to compare our results with [53] and [54], we choose \(\Delta _{+}=3/2\) and 2 in \(d=5\) dimensions. There is a perfect agreement between our results with corresponding cases in [53] and [54]. However, because of the difficulty of a numerical solution, we can only do our study for one value of mass in \(d=6\). Tables IV and V give information about the values of the critical temperature \(T_{c}\) based on \(\rho ^{1/(d-2)}\) for different effects of the mass and nonlinear parameters as well as Gauss–Bonnet parameter. Increasing the Gauss–Bonnet coefficient has the same effect as the larger values of the mass and nonlinear parameters on the critical temperatures. We also face a decrease of the critical temperature for stronger values of \(\alpha \), which renders the condensation harder to form by putting off the appearance of hair on the gravity side, which corresponds to a superconducting phase in boundary field theory. Moreover, the results in \(d=5\) with \({\overline{m}}^{2}=-3/4\) and \(\alpha =0.0001\) are like the outcomes of the corresponding case in Einstein gravity. This is rooted in the fact that, as said before in the \(\alpha \rightarrow 0\) limit, the Einstein case is regained. Meanwhile, Figs. 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 show the behavior of condensation as a function of the temperature for different choices of mass, nonlinearity and Gauss–Bonnet parameters. Increasing each one of these three parameters makes the condensation value increase. Furthermore, the effect of different values of Gauss–Bonnet parameter becomes more and more obvious by increasing the nonlinear parameter b. Based on the obtained results and the same as in [53], the Gauss–Bonnet term does not change the critical exponent of condensation, which means that we face a second order phase transition for all values of \(\alpha \), the same result as Sect. 2.1.

3.2 Conductivity

In order to study the electrical conductivity for the holographic p-wave superconductor in the Gauss–Bonnet gravity, we follow the same approach as Sect. 2.2. By choosing the same perturbation as \(\delta A_{y}=A_{y} e^{-i \omega t}\), we obtain the linearized equation as (15). with the asymptotic behavior (\(r\rightarrow \infty \))

which has a solution as follows:

which is similar to Eq. (17) except the \(L_{\mathrm{{eff}}}^4\) term which shows the influence of Gauss–Bonnet gravity. By pursuing the identical procedure as Sect. 2.2, Eqs. (18), (19), (20) and (21) are regained. So, the electrical conductivity based on a holographic approach in Gauss–Bonnet gravity can be expressed by

Again like Sect. 2.2, the definition of \(\sigma _{yy}\) is the same as \(\sigma _{xx}\) in Ref. [28], which confirms the fact that calculation of \(\sigma _{yy}\) in holographic p-wave superconductors is similar to \(\sigma _{xx}\) in holographic s-wave superconductors. Next, by expanding \(A_{y}\) as Eq. (23) we can plot the behavior of the real and imaginary parts of the conductivity as a function of the frequency for different values of the nonlinearity, mass and Gauss–Bonnet parameters in \(d=5\) and 6 in Figs. 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23. Besides the differences in the figures, they show the same universality trend as the conductivity behavior in the Einstein gravity, which we explained in Sect. 2.2. In \(\omega \rightarrow 0\) limit, the delta function behavior of the real part of the conductivity is related to the imaginary part, which has a pole in this region through the Kramers–Kronig relation. The infinite DC conductivity is a tail of the superconducting phase. On the other hand, at large frequency regime the behavior of the real part of the conductivity can be expressed by \(Re[\sigma ]=\omega ^{(d-4)}\). Furthermore, for a holographic p-wave superconductor in Gauss–Bonnet gravity, \(\omega _{g}\approx 8T_{c}\) is much higher than the BSC value (3.5). This difference originates from the fact that the strong interaction governs the system in the case of holographic superconductors similar to [53]. However, we observe the deviation from 8 by increasing the nonlinearity as well as Gauss–Bonnet parameters. Increasing the nonlinearity and Gauss–Bonnet parameters or decreasing the temperature, while the other two components are fixed, shifts the maximum and minimum values of the real and imaginary parts toward larger frequencies. Based on [53] for fixed values of the temperature, the real and imaginary parts of the conductivity decrease by enlarging the Gauss–Bonnet effect. It is true in some cases in the presence of Maxwell electrodynamics. For example, the behavior of the real part of the conductivity in \(d=5\) with \({\overline{m}}^{2}=-3/4\) confirms this idea, while, in the same dimension with \({\overline{m}}^{2}=0\), it does not follow the same trend. However, this idea does not govern the nonlinear regime. In general, we can say that the gap frequency depends on mass, nonlinearity and Gauss–Bonnet parameters in each dimension. The dependences of the conductivity on the nonlinearity and Gauss–Bonnet parameters are shown in Figs. 24,25, 26 and 27.

4 Summary and conclusion

In this work, by applying the AdS/CFT correspondence in higher dimensional spacetime, we have analyzed the behavior of a holographic p-wave superconductor by considering the higher order corrections on the gravity as well as the gauge field side. First of all, we studied the condensation of the vector field in the presence of a nonlinear correction to the electrodynamics as given in Eq. (3). This equation can be considered as the leading order expansion terms of the well-known Born–Infeld, Logarithmic and Exponential nonlinear electrodynamics. After finding the equations of motion in Einstein gravity, we solved them numerically by applying suitable conditions and investigated the effect of mass, dimension and nonlinear parameters. We found the relation between the critical temperature \(T_{c}\) and \(\rho ^{1/(d-2)}\) in all cases. Then we plotted the behavior of condensation as a function of the temperature. Based on the obtained results, we found that increasing the value of the mass as well as nonlinearity decreases the critical temperature. This renders the condensation harder to form. Also by taking a look at the graphs, we understand that the condensation value increases for a stronger effect of the mass and nonlinearity, which means that vector hair faces difficulty in occurring. It was argued in [40, 43] that the holographic p-wave superconductors undergo a first order phase transition instead of the usual second type in some situations but we did not observe such a behavior.

Next, in Sect. 2.2 we have numerically investigated the behavior of electrical conductivity as a function of the frequency. For this purpose, we applied an electromagnetic perturbation as \(\delta A_{y}=A_{y} e^{-i \omega t}\) on the gravity side, which corresponds to the electrical current in CFT part. We presented the electrical conductivity formula in \(d=4, 5\) and 6 and the graphs of the real and imaginary parts. The conductivity differs based on our choice of mass, dimension and nonlinearity. However, some global trends were observed. Firstly, the real and imaginary parts follow the Kramers–Kronig relation by having a delta function and divergence behavior in the low frequency regime. Infinite DC conductivity is a feature of superconducting phase. Secondly, at large enough frequencies, the behavior of the real part can be interpreted by \(Re[\sigma ]=\omega ^{(d-4)}\). Thirdly, the ratio of \(\omega _{g}/T_{c}\) in all cases is much larger than the BCS value (3.5) because holographic superconductors are strongly coupled. In a holographic setup in many cases we found \(\omega _{g}\simeq 8 T_{c}\), while a deviation from this value occurred by increasing the dimension and by the nonlinearity effect. The presence of nonlinear electrodynamics shifts the gap frequency toward larger values. In Sect. 3.1, with the same procedure as Sect. 2.1, we found the ratio of \(T_{c}/\rho ^{1/(d-2)}\) numerically and obtained the trend of condensation versus temperature for different values of mass, nonlinearity and Gauss–Bonnet parameters in different dimensions for holographic p-wave superconductor in Gauss–Bonnet gravity. Increasing the effect of mass and nonlinear parameter leads to the same behavior as the Einstein case. Furthermore, increasing the Gauss–Bonnet parameter \(\alpha \) hinders the superconducting phase by diminishing the critical temperature. Besides, the Gauss–Bonnet term \(\alpha \) does not change the order of the phase transition. In Sect. 3.2, the electrical conductivity of \((d+1)\)-dimensional holographic p-wave superconductor in Gauss–Bonnet gravity with higher order corrections in gravity and gauge fields was studied. The same as in Sect. 2.2, the conductivity formula and behavior of the real and imaginary parts influenced by mass, nonlinearity and Gauss–Bonnet parameters in different dimensions were obtained. The universal behaviors, in the same way as the Einstein case, were obtained. In addition, increasing the effect of the nonlinear and Gauss–Bonnet parameters or decreasing the temperature shifts the gap energy toward larger frequencies. In general, the gap frequency \(\omega _{g}\) is dependent on mass, nonlinearity and Gauss–Bonnet terms. It would be interesting to investigate the effect of a backreaction in this case.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: The calculations of this paper were done with help of mathematica software and there is no data associated with it.]

References

J.M. Maldacena, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 231 (1998). arXiv:hep-th/9711200v3

S.A. Hartnoll, C.P. Herzog, G.T. Horowitz, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 031601 (2008). arXiv:0803.3295

S.S. Gubser, I.R. Klebanov, A.M. Polyakov, Phys. Lett. B 428, 105 (1998). arXiv:hep-th/9802109

E. Witten, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 253 (1998). arXiv:hep-th/9802150

G.T. Horowitz, M.M. Roberts, Phys. Rev. D 78, 126008 (2008)

J. Ren, JHEP 1011, 055 (2010). arXiv:1008.3904

G.T. Horowitz, Lect. Notes Phys. 828, 313 (2011). arXiv:1002.1722

S.A. Hartnoll, Class. Quantum Gravity 26, 224002 (2009). arXiv:0903.3246

M. Born, L. Infeld, Proc. R. Soc. A 144, 425 (1934)

S.H. Hendi, A. Sheykhi, Phys. Rev. D 88, 044044 (2003). arXiv:1405.6998

H.H. Soleng, Phys. Rev. D 52, 6178 (1995). arXiv:hep-th/9509033

H.R. Salahi, A. Sheykhi, A. Montakhab, Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 575 (2016). arXiv:1608.05025

C.P. Herzog, J. Phys. A 42, 343001 (2009). arXiv:0904.1975

S.S. Gubser, C.P. Herzog, S.S. Pufu, T. Tesileanu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 141601 (2009). arXiv:0907.3510

S.A. Hartnoll, C.P. Herzog, G.T. Horowitz, JHEP 0812, 015 (2008). arXiv:0810.1563

J. Jing, S. Chen, Phys. Lett. B 686, 68 (2010). arXiv:1001.4227

R.G. Cai, L. Li, L.-F. Li, R.-Q. Yang, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 58, 060401 (2015). arXiv:1502.00437

X.H. Ge, B. Wang, S.F. Wu, G.H. Yang, JHEP 1008, 108 (2010). arXiv:1002.4901

X.H. Ge, S.F. Tu, B. Wang, JHEP 09, 088 (2012). arXiv:1209.4272

X.M. Kuang, E. Papantonopoulos, G. Siopsis, B. Wang, Phys. Rev. D 88, 086008 (2013). arXiv:1303.2575

Q. Pan, J. Jing, B. Wang, JHEP 11, 088 (2011). arXiv:1105.6153

R.G. Cai, H.F. Li, H.Q. Zhang, Phys. Rev. D 83, 126007 (2011)

R.G. Cai, Z.Y. Nie, H.Q. Zhang, Phys. Rev. D 82, 066007 (2010)

W. Yao, J. Jing, JHEP 1305, 101 (2013). arXiv:1306.0064

S. Gangopadhyay, D. Roychowdhury, JHEP 05, 002 (2012). arXiv:1201.6520

S. Gangopadhyay, D. Roychowdhury, JHEP 05, 156 (2012). arXiv:1204.0673

A. Sheykhi, D. Hashemi Asl, A. Dehyadegari, Phys. Lett. B 781, 139 (2018). arXiv:1803.05724

A. Sheykhi, A. Ghazanfari, A. Dehyadegari, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 159 (2018). arXiv:1712.04331

Z. Zhao, Q. Pan, S. Chen, J. Jing, Nucl. Phys. B 871, 98 (2013). arXiv:1212.6693

Y. Liu, Y. Gong, B. Wang, JHEP 1602, 116 (2016). arXiv:1505.03603

A. Sheykhi, H.R. Salahi, A. Montakhab, JHEP 1604, 058 (2016). arXiv:1603.00075

A. Sheykhi, F. Shaker, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 26, 1750050 (2017). arXiv:1606.04364

A. Sheykhi, F. Shaker, Can. J. Phys. 94, 1372 (2016). arXiv:1601.05817

A. Sheykhi, F. Shaker, Phys. Lett. B 754, 281 (2016). arXiv:1601.04035

S. I. Kruglov, arXiv:1801.06905

M. Mohammadi, A. Sheykhi, M. Kord Zangeneh, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 654 (2018). arXiv:1805.07377v1

J. Bardeen, L.N. Cooper, J.R. Schrieer, Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175 (1957)

A.P. Mackenzie, Y. Maeno, Phys. B 280, 148 (2000)

R.-G. Cai, S. He, L. Li, L.F. Li, JHEP 1312, 036 (2013)

R.G. Cai, L. Li, L.F. Li, JHEP 1401, 032 (2014). arXiv:1309.4877v3

A. Donos, J.P. Gauntlett, JHEP 12, 091 (2011)

S.S. Gubser, S.S. Pufu, JHEP 0811, 033 (2008)

P. Chaturvedi, G. Sengupta, JHEP 1504, 001 (2015). arXiv:1501.06998v1

M.M. Roberts, S.A. Hartnoll, JHEP 0808, 035 (2008). arXiv:0805.3898

H.B. Zeng, W.M. Sun, H.S. Zong, Phys. Rev. D 83, 046010 (2011). arXiv:1010.5039 [hep-th]

R.G. Cai, Z.Y. Nie, H.Q. Zhang, Phys. Rev. D 83, 066013 (2011). arXiv:1012.5559

L.A. Pando Zayas, D. Reichmann, Phys. Rev. D 85, 106012 (2012). arXiv:1108.4022

D. Momeni, N. Majd, R. Myrzakulov, Europhys. Lett. 97, 61001 (2012). arXiv:1204.1246

S. Gangopadhyay, D. Roychowdhury, JHEP 08, 104 (2012). arXiv:1207.6505v2

M. Mohammadi, A. Sheykhi, M. Kord Zangeneh, Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 984 (2018). arXiv:1901.10540

F. Benini, C.P. Herzog, R. Rahman, A. Yarom, JHEP 1011, 137 (2010). arXiv:1007.1981

F. Benini, C.P. Herzog, A. Yarom, Phys. Lett. B 701, 626 (2011). arXiv:1006.0731

R.G. Cai, Z.Y. Nie, H.Q. Zhang, Phys. Rev. D 82, 066007 (2010). arXiv:1007.3321v2

J.W. Lu, Y.B. Wu, T. Cai, H.M. Liu, Y.S. Ren, M.L. Liu, Nucl. Phys. B 903, 360 (2016)

S.H. Hendi, JHEP 03, 065 (2012)

A. Ritz, R. Delbourgo, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 11, 253 (1996). arXiv:hep-th/9503160

J.T. Liu, P. Szepietowski, Phys. Rev. D 79, 084042 (2009). arXiv:0806.1026

Y. Kats, L. Motl, M. Padi, JHEP 12, 068 (2007). arXiv:hep-th/0606100

D. Anninos, G. Pastras, JHEP 07, 030 (2009). arXiv:0807.3478

D. Wen, H. Yu, Q. Pan, K. Lin, W.L. Qian, Nucl. Phys. B 930, 255 (2018). arXiv:1803.06942v2

K. Skenderis, Quantum Gravity 19, 5849 (2002). arXiv:hep-th/0209067

M. Brigante, H. Liu, R.C. Myers, S. Shenker, S. Yaida, Phys. Rev. D 77, 126006 (2008). arXiv:0712.0805 [hep-th]

M. Brigante, H. Liu, R.C. Myers, S. Shenker, S. Yaida, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 191601 (2008). arXiv:0802.3318 [hep-th]

A. Buchel, R.C. Myers, JHEP 0908, 016 (2009). arXiv:0906.2922 [hep-th]

D.M. Hofman, Nucl. Phys. B 823, 174 (2009). arXiv:0907.1625 [hep-th]

J. de Boer, M. Kulaxizi, A. Parnachev, JHEP 1003, 087 (2010). arXiv:0910.5347 [hep-th]

X.O. Camanho, J.D. Edelstein, JHEP 1004, 007 (2010). arXiv:0911.3160 [hep-th]

A. Buchel, J. Escobedo, R.C. Myers, M.F. Paulos, A. Sinha, M. Smolkin, JHEP 1003, 111 (2010). arXiv:0911.4257 [hep-th]

Acknowledgements

We thank Shiraz University Research Council. The work of AS has been supported financially by Research Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics of Maragha (RIAAM), Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadi, M., Sheykhi, A. Conductivity of the holographic p-wave superconductors with higher order corrections. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 743 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7250-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7250-1