Abstract

This paper shows that the well documented US excess return on its net foreign assets is no exception at the global level: on average, high corporate tax countries earn larger yields on their foreign direct investment assets than on their liabilities, generating an excess return on their net foreign assets consistent with tax-motivated profit shifting by multinational enterprises. Cross-country evidence based on aggregate data is confirmed using detailed firm-level data for France. A quantification exercise suggests that profit shifting inflated the French FDI income balance by €16 to €32 billion (0.7–1.5% of GDP) in 2015, largely explains the excess return on French FDI assets versus liabilities, and has increased substantially over recent years.

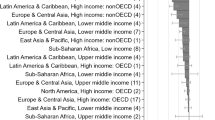

Source: IMF BOP statistics, sample of EU and OECD countries with at least 10 years of data over 2001–2015 (see Appendix Table 15 for the country list). Each data point is a country-year observation

Source: OECD and KPMG

Source: coefficients are reported in column (6) in Appendix Table 18. The omitted category is decile 1 (highest corporate tax host countries)

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

09 November 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-022-00191-7

Notes

See Curcuru et al. (2013) for a survey of the literature.

Most common avoidance schemes include transfer pricing manipulation on intra-firm international transactions and the strategic location of intangibles assets, remunerated through royalties or other exports of services, and of intra-group debt, whose interest is tax-deductible.

Tax avoidance schemes based on the manipulation of transfer prices or the location of intangible assets also affect exports and imports of goods and services (Vicard 2015), while schemes using the location of intra-group debt distort the primary income balance, through flows of interests on intra-group debt, and the cross-border debt stock (Feld et al. 2013).

Under the French participation exemption, parent companies may exclude up to 95% of the dividends distributed by their affiliates (of which they own at least 5% of the shares) from their taxable profit (Direction générale des finances publiques 2017). The US had a residential tax system in which corporations were taxed on their activities worldwide until end 2017. The 2018 tax reform shifted the system toward a more territorial taxation but still feature taxes on worldwide profits (Auerbach 2018).

Interestingly, estimations of missing profits based on different data and identification sources yield similar amounts for France.

Note that the analysis focuses on the income stream generated by foreign asset holding, i.e. interests, dividends or re-invested earnings in the case of FDI. The total return also includes valuation effects related to asset price changes in domestic currency that are not considered here.

Thin capitalization rules restrict the deductibility of interests above a certain debt level and affect the leverage of foreign subsidiaries in different countries (Blouin et al. 2014).

In principle, retained earnings include earnings receivable from any direct investment enterprises. To the best of my knowledge, however, only the US includes re-invested earnings in earnings receivable from direct investment enterprises, so that only dividends of second order affiliates are reported for other countries.

Real-estate investment is calculated at market value through cumulative flows valued at historical cost and updated yearly using various price indexes.

14.5% and 0.8% using the top 15 tax havens and OECD lists, respectively.

The same pattern holds when using effective tax rates. Using the marginal effective tax rate, the differential increased from 0 to 6 percentage points with respect to the rest of the world, and from 2 to 7 percentage points with respect to other EU countries.

Note that the \(R^2\) more than doubles when tax havens are excluded from the sample of countries, and corporate tax rates explain 21% of the variance of FDI yield differentials.

Balance of payments data feature breaks in statistical series that prevent comparisons over time. In columns (6) and (7), the sample is restricted to observations after the last break in statistical series, as indicated by the IMF BOP Statistics.

As emphasized in the previous section, the sign of \(TH_{c}\) and \(TH_{p}\) is ambiguous in column (1) including both interests on intra-group debt and dividends and reinvested earnings. Note that the only declaring country c listed in the tax haven list is Ireland.

\(FE_{jt}\) control for intangible assets specific to the multinational enterprise, and their variation over time, which are major determinants of firm value and their production processes, but not for the location of specific intangible assets (trademark, patents, etc.) across affiliates. Since intangibles assets are not necessarily or incompletely included in capital stocks when developed in-house (Dischinger and Riedel 2011), the estimated coefficients \(\beta _1\) and \(\beta _2\) in Eq. 4 account for any strategic location of intangible assets not measured in FDI stocks to shift profit in low-tax countries or tax havens.

Appendix Table 20 shows that the results are robust to different levels of clustering.

Statutory tax rates may overestimate effective marginal tax rates in tax havens; column (2) however shows that it does not bias the coefficient on the corporate tax differential.

The OECD Country Risk Classification measures the country credit risk and the likelihood that a country will service its external debt. It allocates countries in 8 categories based on a quantitative model and qualitative assessments of country risk experts from Export Credit Agencies, and is revised at least once a year. I measure country risk as the logarithm of one plus the country risk category. Measuring country risk using dummies by category does not change the results.

Data are from CEPII’s Gravity dataset (Head and Mayer 2014).

The fact that larger MNEs have more bargaining power to reduce their domestic tax rate (Egger et al. 2018) could also confound the size results.

The average return of all subsidiaries of a given multinational, as estimated by the parent × year fixed effects in Eq. 4, remains parent specific.

FDI income inflows are adjusted for missing yields (e.g. single affiliate parents) at the country level proportionally to their stock share.

Figure 8 in Appendix shows the goodness of fit of the model prediction: predicted FDI income credits fit closely observed FDI income credits in level and over time.

Since columns (2) and (3) of Table 12 are based on specifications without a tax haven dummy, only the tax differential is set to zero for computing counterfactual FDI yields.

Aggregate yield differentials estimated from firm-level data may differ from the aggregate figures reported in Table 14 because of the computation procedure or some corrections in the production of the balance of payments data from the Survey data.

Figure 9 in the Appendix provides the details for credit and debit separately.

At the 38% French corporate tax rate in 2015, before-tax under-reported profits by French subsidiaries of foreign parents equal €13.9 billion. The average tax rate on profits reported by foreign subsidiaries of French parents is \(1-\frac{16.8}{22.0}=23\%\).

Bruner et al. (2018) estimate missing profits in the United States of a similar order of magnitude (1.5% of GDP in 2014). Note that the approach for estimating profit shifted proposed here differs from the methodology based on formulary apportionment applied by Guvenen et al. (2017) (which requires data on multinational activities collected only by the US BEA).

Flows of interests on intra-firm debt represent 8% of total investment income credit only but 25% of investment income debits in 2014.

References

Alcalin, J., and O. Blanchard. 2016. What does measured FDI actually measure? Policy Brief 16-17, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Altshuler, R., and H. Grubert. 2006. Governments and multinational corporations in the race to the bottom. Tax Notes International 41(5): 459–474.

Alvarez-Martinez, M., S. Barrios, D. d’Andria, M. Gesualdo, G. Nicodème, and J. Pycroft. 2018. How large is the corporate tax base erosion and profit shifting? A general equilibrium approach. CEPR Discussion Papers 12637, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.

Auerbach, A.J. 2018. Measuring the effects of corporate tax cuts. Journal of Economic Perspectives 32(4): 97–120.

Banque de France. 2015. Methodology: The French balance of payments and international investment position. https://www.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/media/2016/11/16/bdp-gb-methodologie.pdf.

Bilicka, K.A. 2019. Comparing UK tax returns of foreign multinationals to matched domestic firms. American Economic Review 109(8): 2921–2953.

Blouin, J., H. Huizinga, L. Laeven, and G. Nicodème. 2014. Thin capitalization rules and multinational firm capital structure. Taxation Papers 42, Directorate General Taxation and Customs Union, European Commission.

Blouin, J. and L. Robinson. 2019. Double counting accounting: How much profit of multinational enterprises is really in tax havens? mimeo.

Bosworth, B., S.M. Collins, and G. Chodorow-Reich. 2007. Returns on FDI: Does the U.S. really do better? Brooking Trade Forum, 177–219.

Bouvatier, V., G. Capelle-Blancard, and A.-L. Delatte. 2017. Banks defy gravity in tax havens. Working Papers 2017-16, CEPII research center.

Bruner, J., D. Rassier, and K.J. Ruhl. 2018. Multinational profit shifting and measures throughout economic accounts. In The challenges of globalization in the measurement of national accounts, NBER Chapters. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Clausing, K.A. 2016. The effect of profit shifting on the corporate tax base in the United States and beyond. National Tax Journal 69(4): 905–934.

Cobham, A. and P. Jansky. 2017. Global distribution of revenue loss from tax avoidance: Re-estimation and country results. WIDER Working Paper Series 055, World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNU-WIDER).

Cosslett, S. 1991. Semiparametric estimation of a regression model with sample selectivity. In Nonparametric and semiparametric methods in econometrics and statistics, ed. A.B. William, J. Powell, and G. Tauchen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Curcuru, S.E., T. Dvorak, and F.E. Warnock. 2008. Cross-border returns differentials. Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(4): 1495–1530.

Curcuru, S.E., T. Dvorak, and F.E. Warnock. 2010. Decomposing the U.S. external returns differential. Journal of International Economics 80: 22–32.

Curcuru, S.E., D. Thomas, and F.E. Warnock. 2013. On returns differentials. Journal of International Money and Finance 36: 1–25.

Davies, R.B., J. Martin, M. Parenti, and F. Toubal. 2018. Knocking on Tax Haven’s door: Multinational firms and transfer pricing. The Review of Economics and Statistics 100(1): 120–134.

Desai, M.A., C.F. Foley, and J.J. Hines. 2006. The demand for tax haven operations. Journal of Public Economics 90(3): 513–531.

Direction générale des finances publiques. 2017. Overview of the French Tax System. https://www.impots.gouv.fr/portail/files/media/1_metier/5_international/french_tax_system.pdf.

Dischinger, M., and N. Riedel. 2011. Corporate taxes and the location of intangible assets within multinational firms. Journal of Public Economics 95(7): 691–707.

Dowd, T., P. Landefeld, and A. Moore. 2017. Profit shifting of U.S. multinationals. Journal of Public Economics 148: 1–13.

Egger, P., and S. Bosenberg. 2017. R &D tax incentives. Economic Policy, 43–80.

Egger, P., N. Strecker, and B. Zoller-Rydzek. 2018. Estimating bargaining-related tax advantages of multinational firms. CEPR Discussion Papers 13143.

Feld, L.P., J.H. Heckemeyer, and M. Overesch. 2013. Capital structure choice and company taxation: A meta-study. Journal of Banking & Finance 37(8): 2850–2866.

Fisman, R., and S.-J. Wei. 2004. Tax rates and tax evasion: Evidence from “Missing Imports” in China. Journal of Political Economy 112(2): 471–500.

Forbes, K., I. Hjortsoe, and T. Nenova. 2017. Current account deficits during heightened risk: Menacing or mitigating? The Economic Journal 127(601): 571–623.

Garcia-Bernardo, J., J. Fichtner, F.W. Takes, and E.M. Heemskerk. 2017. Uncovering offshore financial centers: Conduits and sinks in the global corporate ownership network. Scientific Reports 7(6246): 1–10.

Gourinchas, P.-O., and H. Rey. 2007. From world banker to world venture capitalist: U.S. external adjustment and the exorbitant privilege. In G7 current account imbalances: Sustainability and adjustment, NBER Chapters, 11–66. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Gourinchas, P.-O., H. Rey, and N. Govillot. 2010. Exorbitant privilege and exorbitant duty. IMES Discussion Paper Series 10-E-20, Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan.

Greene, W. 2004. The behaviour of the maximum likelihood estimator of limited dependent variable models in the presence of fixed effects. The Econometrics Journal 7(1): 98–119.

Gumpert, A., Jr., J.R. Hines, and M. Schnitzer. 2016. Multinational firms and tax havens. The Review of Economics and Statistics 98(4): 713–727.

Guvenen, F., J. Raymond, J. Mataloni, D.G. Rassier, and K.J. Ruhl. 2017. Offshore profit shifting and domestic productivity measurement. NBER Working Papers 23324, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Habib, M.M. 2010. Excess returns on net foreign assets: The exorbitant privilege from a global perspective. Working Paper Series 1158, European Central Bank.

Head, K., and T. Mayer. 2014. Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In Handbook of international economics, volume 4 of handbook of international economics, ed. G. Gopinath, E. Helpman, and K. Rogoff, 131–195. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Heckman, J.J. 1979. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1): 153–161.

Hines, James R., and E.M. Rice. 1994. Fiscal paradise: Foreign tax havens and American business. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 109(1): 149–82.

Huizinga, H., and L. Laeven. 2008. International profit shifting within multinationals: A multi-country perspective. Journal of Public Economics 92(5–6): 1164–1182.

Janský, P., and M. Palanský. 2019. Estimating the scale of profit shifting and tax revenue losses related to foreign direct investment. International Tax and Public Finance 26: 1048–1103.

Johannesen, N., T. Tørsløv, and L. Wier. 2016. Are less developed countries more exposed to multinational tax avoidance? Method and evidence from micro-data. Technical report.

Knetsch, T.A., and A.J. Nagengast. 2017. Penny wise and pound foolish? On the income from Germany’s foreign investments. Review of World Economics (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv) 153(4): 753–778.

Lane, P.R., and G.M. Milesi-Ferretti. 2009. Where did all the borrowing go? A forensic analysis of the U.S. external position. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 23(2): 177–199.

Obstfeld, M. 2012. Does the current account still matter? American Economic Review 102(3): 1–23.

Obstfeld, M., and K.S. Rogoff. 2005. Global current account imbalances and exchange rate adjustments. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 36(1): 67–146.

OECD. 2000. Towards global tax co-operation: Progress in identifying and eliminating harmful tax practices. Progress report to the g20, OECD.

Olsen, R.J. 1980. A least squares correction for selectivity bias. Econometrica 48(7): 1815–1820.

Riedel, N. 2018. Quantifying international tax avoidance: A review of the academic literature. Review of Economics 69(2): 169–181.

Rogoff, K.S., and T. Tashiro. 2015. Japan’s exorbitant privilege. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 35(C): 43–61.

Tørsløv, T.R., L.S. Wier, and G. Zucman. 2018. The missing profits of nations. NBER Working Papers 24701, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Van’t Riet, M., and A. Lejour. 2018. Optimal tax routing: Network analysis of FDI diversion. International Tax and Public Finance 25(5): 1321–1371.

Vella, F. 1998. Estimating models with sample selection bias: A survey. Journal of Human Resources 33(1): 127–169.

Vicard, V. 2015. Profit shifting through transfer pricing: Evidence from French firm level trade data. Working papers 555, Banque de France.

Weichenrieder, A. 2009. Profit shifting in the EU: Evidence from Germany. International Tax and Public Finance 16(3): 281–297.

Wier, L., and H. Reynolds. 2018. Big and ‘unprofitable’: How 10% of multinational firms do 98% of profit shifting. UNU WIDER Working Paper Series 111, UNU-WIDER.

Wright, T., and G. Zucman. 2018. The exorbitant tax privilege. NBER Working Papers 24983, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Zucman, G. 2013. The missing wealth of nations: Are Europe and the U.S. net debtors or net creditors? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(3): 1321–1364.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The were two formatting mistakes in table 7.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Some Specificities of the French Balance of Payments Data

An important statistical issue for the computation of yield differentials in the French case is the treatment of intra-group loans. Intra-group debt is registered as FDI in the stock data but the related incomes are reported under the “other investment income” item of the “investment income” account up to 2012. Such discrepancy in income flows and stocks of FDI biases the denominator of Eq. 1 when computed using aggregate FDI stocks as provided by the IMF.

I use detailed FDI stock data provided by the Banque de France to correct for this bias, using only equity capital stock of FDI in the computation of yields on FDI and allocating the stock of intra-group debt in the ‘other investments’ category.

Table 13 shows that correcting for intra-group debt increases average yields on FDI from 4.8% (total FDI) to 6.7% (equity capital) for assets on average over the 2002/2012 period and from 3.0 to 4.6% for liabilities. Note that the correction increases not only the level of yields on FDI but also slightly magnifies the differential between assets and liabilities. Columns (2) and (4) show that the yield differential and the correction remain of similar magnitude when applied to stock data in book value instead of market value.

Income on intra-group debt is reported only beginning in 2012. Column (5) of Table 13 shows that the yields on intra-firm debt are indeed lower than on FDI equity and that the differential is negative, i.e. multinational firms located in France pay on average higher interest rates on their intra-firm debt than multinational companies located abroad do on their debt held by French resident affiliated firms. Such a pattern is consistent with profit shifting by multinationals through intra-firm debt.Footnote 35

The French excess return: Table 14 reports the yields on asset and liability by class of asset over the 2001/2014 period. It shows a positive average yield differential between assets and liabilities for FDI, especially over 2009/2014, but not for other classes of assets. The yield on FDI assets is 6.4% on average, against 4.3% on liabilities, generating a 2.1 percentage point differential. The corresponding differential is -1.0 pp on portfolio equity, 0.4 pp on portfolio debt and -0.1 pp on other investments, confirming that the positive yield differential is specific to FDI in the French case. Such a pattern of yield differentials with asset classes in a high-tax country like France is consistent with tax-motivated profit shifting by multinational companies.

The middle and bottom panels of Table 14 additionally report yields on French assets and liabilities by sub-period. The yield differential on FDI is larger over the 2009-2014 period than at the beginning of the 2000s, as is the yield differential on total investment. This was a period during which France increasingly became a high-tax country relative to its partners (see Fig. 2). Since gross stock positions are much larger than net positions and growing, the 2.5 percentage points differential on FDI also applies to large asset and liability stocks, and explains the gradual appearance of an income puzzle in France: despite a negative net international investment position from 2006, the income balance has remained positive.

Appendix 2: Data tables

Appendix 3: Additional robustness tables

Appendix 4: Quantification: additional figures

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.