Abstract

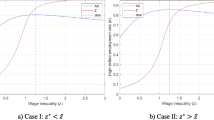

The contrasting effects of labour market rigidity on efficiency are investigated in a model where technological change is non-general purpose and different types of skills are available to workers. Ex ante efficiency calls for high labour market rigidity, as this favours workers’ acquisition of specific skills which have higher productivity in equilibrium. Ex post efficiency calls for low market rigidity, as this allows more workers to transfer to the innovating sector of the economy. The trade-off between these two mechanisms results in an inverse-U shaped relationship between output and labour market rigidity, which implies that a positive level of labour market rigidity is in general beneficial for the economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some of the aspects that have been analysed are firing costs (Bentolila and Bertola 1990), the unemployment benefit system (Layard et al. 1991), the loss of human capital during unemployment spells (Ljungqvist and Sargent 2002), insider-outsiders relations (Blanchard and Summers 1987), the inability of systems to adjust either to macroeconomic shocks (Blanchard and Wolfers 2000) or to microeconomic ones (Gottshalk and Moffitt 1994).

Atkinson (1999) has objected that the rolling back of the welfare state to which the process of liberalization would lead may in fact decrease labour markets efficiency. Nickell and Layard (1999) conclude that the empirical evidence on the negative impact of labour market rigidity is limited to some institutions, mainly unemployment benefits and strong and uncoordinated unions, but is at best weak for the remaining ones. Others have pointed to the social costs associated with market liberalization (Rodrik 1997), and have noted that welfare institutions tend to be larger in more open countries, thus underlining their positive function in absorbing macroeconomic shocks (Agell 1999). See also Howell et al. (2007).

Firms too will have fewer incentives to impart on-the-job training leading to specific human capital in more slack labour markets, given the higher probability of losing this investment should the worker leave the firm. This model will not take into account the latter aspect, as it will only focus on workers’ incentives.

GP and non-GP innovations are likely to be interlinked. The introduction of a GPT is likely to generate different paths of technical innovations in different sectors and different firms, thus triggering what are in fact non-GP innovations.

It might appear counter-intuitive that market rigidity engenders a cost for a worker, rather than representing a form of protection. However, this characteristic of the model may be easily made more realistic by modelling explicitly managers’ choices, and assuming that the transfer cost was paid by the firm rather than by the worker. Even in this case, transfer costs would hinder workers’ cross-sector transferability and would reduce the possibility of being re-employed in the innovating sector of the economy. Hence, the same results would be obtained as in the present form of the model.

References

Agell, J. (1999). On the Benefits of rigid labour markets: Norms, market failures and social insurance. Economic Journal, F143–F164

Arthur, W. B. (1989). Competing technologies, increasing returns, and lock-in by historical events. Economic Journal, 1989, 116–131.

Atkinson, A. B. (1999). The economic consequences of rolling back the welfare state. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Atkinson, A. B., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1969). A new view of technological change. Economic Journal, 79, 573–578.

Autor, D. H., Kerr, W. R., & Kugler, A. D. (2007). Does employment protection reduce productivity? Evidence from US States. Economic Journal, 117(521), F189–F217.

Bartelsman, E., Bassanini, A., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R., Scarpetta, S., & Schank, T. (2004). The spread of ICT and productivity growth: is Europe really lagging behind in the new economy? In D. Cohen, P. Garibaldi, & S. Scarpetta (Eds.), The ICT revolution: Productivity differences and the digital divide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bassanini, A., & Duval, R. (2006). Employment patterns in OECD countries: Reassessing the role of policies and institutions. In OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 486. OECD Publishing.

Bassanini, A., Nunziata, L., & Venn, D. (2009). Job protection legislation and productivity growth in OECD countries. Economic Policy, 24(58), 349–402.

Becker, Gary. (1964). Human capital. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Belot, M., Boone, J., & Van Ours, J. (2007). Welfare-improving employment protection. Economica, 74(295), 381–396.

Bentolila, S., & Bertola, G. (1990). Firing costs and labour demand: How bad is eurosclerosis? Review of Economic Studies, 57(3), 381–402.

Bertola, G. (1990). Job security, employment and wages. European Economic Review, 34(4), 851–879.

Blanchard, Oliver, & Summers, L. H. (1987). Hysteresis in unemployment. European Economic Review, 31, 288–295.

Blanchard, O., & Wolfers, J. (2000). The role of shocks and institutions in the rise of european unemployment: The aggregate evidence. Economic Journal, 110, 1–33.

Bresnahan, T. F., & Trajtenberg, M. (1995). General purpose technologies ‘engines of growth’? Journal of econometrics, 65(1), 83–108.

Burgess, S., Knetter, M., & Michelacci, C. (2000). Employment and output adjustment in the OECD: A disaggregate analysis of the role of job security provisions. Economica, 67(267), 419–435.

Caballero, R. J., Cowan, K. N., Engel, E. M., & Micco, A. (2013). Effective labor regulation and microeconomic flexibility. Journal of Development Economics, 101, 92–104.

Cahuc, P., & Koeniger, W. (2007). Feature: Employment protection legislation. Economic Journal, 117(521), F185–F188.

Cingano, F., Leonardi, M., Messina, J., & Pica, G. (2010). The effects of employment protection legislation and financial market imperfections on investment: Evidence from a firm-level panel of EU countries. Economic Policy, 25(61), 117–163.

David, P. A. (1985). Cliometrics and QWERTY. American Economic Review, 75, 332–337.

David, P. A., & Greenstein, S. (1990). The economics of compatibility standards: An introduction to recent research 1. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 1(1-2), 3–41.

DeFreitas, G., & Marshall, A. (1998). Labour surplus, worker rights and productivity growth: A comparative analysis of Asia and Latin America. Labour, 12(3), 515–539.

Dosi, G. (1988). Sources, procedures and microeconomic effects of innovations. Journal of Economic Literature, 26, 1120–1171.

Gottschalk, Peter, & Moffitt, Robert. (1994). The growth of earnings instability in the U.S. labor market. Brooking Papers Econ. Activity, 2, 217–254.

Grimalda, G. (2007). Labour market rigidity and economic efficiency with non-general purpose technical change. CSGR Working paper series 186/05.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (Eds.). (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hopenhayn, H., & Rogerson, R. (1993). Job turnover and policy evaluation: A general equilibrium analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 101(5), 915.

Howell, D. R., Baker, D., Glyn, A., & Schmitt, J. (2007). Are protecive labor market institutions at the root of unemployment? A critical review of the evidence. Capitalism and Society, 2 (1, 1).

Ichino, A., & Riphahn, R. T. (2005). The effect of employment protection on worker effort: Absenteeism during and after probation. Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(1), 120–143.

Jovanovic, Boyan, & Nyarko, Yaw. (1996). Learning by doing and the choice of technology. Econometrica, 64(6), 1299–1310.

Koeniger, W. (2005). Dismissal costs and innovation. Economics Letters, 88(1), 79–84.

Kugler, A. D., Jimeno, J. F., & Hernanz, V. (2003). Employment consequences of restrictive permanent contracts: Evidence from Spanish labor market reforms (No. 657). IZA Discussion paper series.

Lagos, R. (2006). A model of TFP. Review of Economic Studies, 73(4), 983–1007.

Layard, R., Nickell, S., & Jackman, R. (1991). Unemployment: Macroeconomic performance and the labour market. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lazear, E. P. (1990). Job security provisions and employment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105(3), 699–726.

Ljungqvist, L. & Sargent, T. (2002). The European employment experience. CEPR Discussion Paper N. 3543

Micco, A. (2006). The economic effects of employment protection: evidence from international industry-level data (No. 2433). IZA Discussion Papers.

Mookherjee, D., & Ray, D. (2003). Persistent inequality. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 369–393.

Mortensen, D. T., & Pissarides, C. A. (1994). Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. The review of economic studies, 61(3), 397–415.

Nickell, S. J. (1978). Fixed costs, employment and labour demand over the cycle. Economica, 45(180), 329–345.

Nickell, S., & Layard, R. (1999). Labor market institutions and economic performance. Handbook of labor economics, 3, 3029–3084.

Nickell, S., Nunziata, L., & Ochel, W. (2005). Unemployment in the OECD since the 1960s. What do we know?*. The Economic Journal, 115(500), 1–27.

OECD Employment Outlook. (2004). Paris: OECD

Petit, Pascal, & Soete, Luc (Eds.). (2001). Technology and the future of European employment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Richard, L., & Stephen, N. (1998). Labour market institutions and economic performance. Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper 0407

Rigolini, J. (2004). Educational technologies, wages, and technological progress. Journal of Development Economics, 75(1), 55–77.

Riphahn, R. T. (2004). Employment protection and effort among German employees. Economics Letters, 85(3), 353–357.

Rodrik, Dani. (1997). Has globalization gone too far?. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

Saint-Paul, Gilles. (2002). The political economy of employment protection. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 672–704.

Soskice, D. (1997). German technology policy, innovation, and national institutional frameworks. Industry and Innovation, 4(1), 75–96.

Summers, L. H. (1989). Some simple economics of mandated benefits. American Economic Review, pp 177–183.

Violante, G. L., Howitt, P., & Aghion, P. (2002). General purpose technology and wage inequality. Journal of Economic Growth, 7(4), 315–345.

Vivarelli, Marco. (1995). The economics of technology and employment: Theory and empirical evidence. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Wasmer, E. (2006). General versus specific skills in labor markets with search frictions and firing costs. American Economic Review, 96(3), 811–831.

Acknowledgments

I thank Donatella Gatti for useful discussions on the basic ideas of this paper, and Elena Meschi for her comments to the previous draft of the paper. I also thank two anonymous referees for their comments, and Karen Whyte for efficient proofreading and assistance. All errors are my sole responsibility. I acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant ECO 2011-23634), Bancaixa (P1·1A2010-17), Junta de Andalucía (P07-SEJ-03155), and Generalitat Valenciana (grant GV/2012/045).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grimalda, G. Can labour market rigidity foster economic efficiency? A model with non-general purpose technical change. Eurasian Bus Rev 6, 79–99 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-015-0024-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-015-0024-2