Abstract

Background

Fast-acting insulin aspart (faster aspart) is insulin aspart (IAsp) in a new formulation aiming to mimic the fast endogenous prandial insulin release more closely than currently available insulin products. In a post hoc analysis of pooled data from six clinical pharmacology trials, the pharmacological characteristics of faster aspart and IAsp were compared.

Methods

The analysis included 218 adult subjects with type 1 diabetes from six randomised, double-blind, crossover trials in the faster aspart clinical development programme. Subjects received subcutaneous dosing (0.2 U/kg) of faster aspart and IAsp. In three trials, a 12-h euglycaemic clamp was performed (target 5.5 mmol/L; 100 mg/dL) to assess pharmacodynamics.

Results

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles were left-shifted for faster aspart versus IAsp. Onset of appearance occurred 4.9 min earlier (95% confidence interval [CI] faster aspart-IAsp: [−5.3 to −4.4], p < 0.001), early exposure (AUCIAsp,0–30min) was two times greater (estimated ratio faster aspart/IAsp 2.01 [1.87–2.17], p < 0.001) and offset of exposure (t Late 50% Cmax) occurred 12.2 min earlier [−17.9 to −6.5] (p < 0.001) for faster aspart versus IAsp. Accordingly, onset of action occurred 4.9 min earlier [−6.9 to −3.0] (p < 0.001), early glucose-lowering effect (AUCGIR,0–30min) was 74% greater (1.74 [1.47–2.10], p < 0.001) and offset of glucose-lowering effect (t Late 50% GIRmax) occurred 14.3 min earlier [−22.1 to −6.5] (p < 0.001) for faster aspart versus IAsp. Total exposure and total glucose-lowering effect did not differ significantly between treatments.

Conclusions

Faster aspart has the potential to better mimic the physiologic prandial insulin secretion and thereby to improve postprandial glucose control compared with IAsp.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02035371, NCT01924637, NCT02131246, NCT02033239, NCT02003677, NCT01618188.

Similar content being viewed by others

In this pooled analysis of six clinical pharmacology trials in adult subjects with type 1 diabetes, accelerated pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of fast-acting insulin aspart (faster aspart) compared with insulin aspart (IAsp) were consistently observed across all trials included. |

The pooled analysis showed an approximately 5 min earlier onset of appearance, a two times higher early insulin exposure and a 74% greater early glucose-lowering effect for faster aspart versus IAsp. |

Offset of exposure and glucose-lowering effect occurred 12–14 min earlier with faster aspart than with IAsp. |

1 Introduction

It is well-established that focusing on improvements in glycaemic control in patients with diabetes reduces the risk of developing microvascular complications [1, 2]. Addressing postprandial glucose excursions is important for improving overall glycaemic control, particularly in patients with mild to moderate overall hyperglycaemia [3, 4]. Thus, focus on postprandial glucose control seems to be a necessity to achieve glycaemic targets in more patients with diabetes.

In healthy individuals ingesting a meal, immediate endogenous insulin secretion leads to an inhibition of hepatic glucose production, which is important for postprandial glucose control [5]. Accordingly, in patients with diabetes, fast absorption and early action of subcutaneously administered mealtime insulin are essential goals in order to counteract postprandial hyperglycaemia, at least in part through inhibition of hepatic glucose production [6, 7]. Another objective is to achieve an appropriately short duration of action, thereby reducing the risk of late postprandial hypoglycaemia [7]. Although current rapid-acting insulin analogues have advantages over regular human insulin in terms of accelerated absorption, earlier onset of action and shorter duration of action [6, 8, 9], absorption of current rapid-acting insulin products still occurs considerably slower than endogenous prandial insulin release in the healthy state [7, 9].

Fast-acting insulin aspart (faster aspart) is insulin aspart (IAsp) in a new formulation in which two additional excipients (l-arginine and niacinamide) have been added. l-arginine and niacinamide are both included in the US FDA database of inactive ingredients in products for injection at higher concentrations than present in faster aspart [10]. In faster aspart, l-arginine serves as a stabilising agent, while niacinamide is responsible for accelerated initial absorption after subcutaneous administration. A proposed mechanism for the latter is that niacinamide promotes the formation of IAsp monomers in the subcutis and augments the permeation rate of IAsp across capillary endothelial cells [11].

The aim of the current investigation was to compare the pharmacological characteristics between faster aspart and IAsp in a post hoc analysis of pooled data from all available and relevant clinical pharmacology trials in the faster aspart clinical development programme. The focus of the investigation was onset of exposure and glucose-lowering effect, early exposure and glucose-lowering effect, as well as offset of exposure and glucose-lowering effect. The pooled analysis has been conducted in order to obtain a robust summary of the differences in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties between faster aspart and IAsp in adult subjects with type 1 diabetes.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This report presents a post hoc analysis of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of faster aspart compared with IAsp based on data from individual phase I, randomised, double-blind, crossover trials (Online Resource 1, Table S1). A total of six trials contributed with pharmacokinetic data, while the three trials using a glucose clamp also contributed with pharmacodynamic data (see the Study Procedures and Assessments section). Trials were conducted at the Children’s and Youth Hospital AUF DER BULT, Hannover, Germany (Trial 1) [12], Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University of Graz, Austria (Trials 2 and 3) and Profil, Neuss, Germany (Trials 4, 5 and 6) [13–15]. Irrespective of trial site, comparable overall methodology was used. Furthermore, the trials shared several characteristics, such as the crossover design and the inclusion of IAsp as the comparator. Therefore, it was deemed valid to perform a pooled analysis of the six trials.

In each trial, the protocol, protocol amendments, consent form and subject information sheets were reviewed and approved by health authorities, according to local regulations, and by local ethics committees prior to trial initiation. All trials were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. Before any trial-related activities were initiated, written informed consent was obtained from the participating subjects. The trials were registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02035371 (Trial 1), NCT01924637 (Trial 2), NCT02131246 (Trial 3), NCT02033239 (Trial 4), NCT02003677 (Trial 5), NCT01618188 (Trial 6).

2.2 Study Population

The pooled analysis was based on data from 218 adult subjects with type 1 diabetes aged 18–64 years (both inclusive). For two of the trials, a subset of the full trial population was included because these trials also enrolled subjects aged <18 years (Trial 1) or >64 years (Trial 5).

Key inclusion criteria for each trial are shown in Online Resource 1, Table S1. In addition, all subjects received treatment with multiple daily insulin injections or insulin pump therapy for at least 12 months with total insulin dose <1.2 (I)U/kg/day and bolus insulin dose <0.7 (I)U/kg/day (and bolus insulin dose ≥0.3 (I)U/kg/day in Trials 1, 2 and 3). General exclusion criteria were clinically significant concomitant diseases (malignant neoplasms or cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, haematological, dermatological, neurological or psychiatric diseases), donation of any blood or plasma in the past month or more than 500 mL within 3 months prior to screening, smoking, or current treatment with drug(s) which might interfere with glucose metabolism. Pregnant or breastfeeding women were also excluded.

2.3 Study Procedures and Assessments

In all trials, subjects received single subcutaneous dosing of 0.2 U/kg faster aspart (100 U/mL; Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) and IAsp (NovoRapid®; 100 U/mL; Novo Nordisk) into a lifted skin fold of the lower abdominal wall above the inguinal area. There was a washout period of 3–12 days (3–15 days in Trial 4) between dosing visits, where subjects resumed their usual insulin treatment. Furthermore, subjects’ current insulin therapy was washed out before each dosing of the trial product: Subjects were excluded from the dosing visit if they had received insulin degludec within 72 h prior to dosing, insulin glargine or insulin detemir within 48 h prior to dosing, intermediate-acting insulin (such as neutral protamine Hagedorn [NPH] insulin) within 22 h prior to dosing, or IAsp within 12 h (for bolus) or 8 h (for basal infusion using a pump) prior to dosing.

Blood samples for serum IAsp assessment were taken within 2 min before dosing (within 5 min before dosing in Trial 6), then every 2 min from dosing until 20 min post-dosing, every 5 min from 20 to 80 min, every 10 min from 80 min to 2 h, every 15 min from 2 to 3 h (from 2 to 2.5 h in Trial 4), and then at 3, 3.5, 4, 5 (not Trial 4), 5.5 (only Trial 4), 6 (not Trial 4), 7, 8 (not Trial 4), 9 (only Trial 4), 10 (not Trial 4) and 12 h post-dosing. A validated IAsp specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 10 pmol/L was used to measure free serum IAsp concentrations (polyethylene glycol-precipitated).

In Trials 4, 5 and 6, which were included in the pharmacodynamic analysis, an automated euglycaemic glucose clamp, with a target blood glucose concentration of 5.5 mmol/L (100 mg/dL), was performed for 12 h post-dosing (ClampArt®, Profil, Neuss, Germany, in Trials 4 and 5; Biostator®, MTB Medizintechnik, Amstetten, Germany, in Trial 6). The clamp was terminated earlier than 12 h post-dosing in case blood glucose was consistently above 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) without the need for intravenous glucose infusion during the last 30 min. Details of the glucose clamp procedure have previously been provided by Heise et al. [15]. In Trials 1, 2 and 3, subjects underwent a standardised liquid meal test for 6 h after dosing (data not included in the pooled pharmacodynamic analysis).

In Trial 4, subjects received three dose levels (0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 U/kg) of faster aspart and IAsp, as well as two additional doses of either 0.2 U/kg faster aspart or 0.2 U/kg IAsp at a total of eight dosing visits. Results from all 0.2 U/kg dosing visits are included in the current pooled analysis. In Trial 6, subjects received two formulations of faster aspart, but only data for the formulation being pursued in further clinical development are included in the current pooled analysis.

2.4 Study Endpoints

The onset was assessed by the following endpoints: onset of appearance, time to 50% of maximum IAsp concentration in the early absorption phase of the pharmacokinetic profile (t Early 50% Cmax), time to maximum IAsp concentration (t max), onset of action, time to 50% of maximum glucose infusion rate (GIR) in the early part of the GIR profile (t Early 50% GIRmax), and time to maximum GIR (t GIRmax). Onset of appearance was derived as the time from trial product administration until the first time serum IAsp concentration ≥10 pmol/L (the assay LLOQ), while onset of action was derived as the time from trial product administration until the blood glucose concentration had decreased at least 0.3 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) from baseline.

Early insulin exposure and early glucose-lowering effect were evaluated by deriving the early partial areas under the curve (AUCs) for serum IAsp and GIR, both within the first 2 h after dosing.

Offset of insulin exposure and glucose-lowering effect were evaluated by the following endpoints: time to 50% of maximum IAsp concentration in the late part of the pharmacokinetic profile (t Late 50% Cmax), the partial AUCIAsp from 2 h (AUCIAsp,2–t), time to 50% of maximum GIR in the late part of the GIR profile (t Late 50% GIRmax) and the partial AUCGIR from 2 h (AUCGIR,2–t).

Overall insulin exposure and glucose-lowering effect were evaluated by calculating total IAsp exposure (AUCIAsp,0–t), maximum IAsp concentration (C max), total glucose-lowering effect (AUCGIR,0–t) and maximum GIR (GIRmax).

In the derivation of onset of appearance and AUCIAsp,0–15 min, the IAsp concentration was imputed between trial product administration and the first IAsp concentration above the assay LLOQ using compartmental modelling as previously described [13]. For consistency, this approach was also used for the calculation of all other AUCIAsp endpoints. AUCIAsp,2–t and AUCIAsp,0–t were derived by calculating the AUC until the time of the last quantifiable serum IAsp concentration, and then extrapolating until the last pharmacokinetic sampling time point of 12 h based on the terminal slope. AUCGIR,2–t and AUCGIR,0–t were calculated until the time of the last GIR observation >0. Endpoints were derived from the raw profiles, except for t Early 50% GIRmax, t Late 50% GIRmax, GIRmax and t GIRmax, which were derived from GIR profiles smoothed by local regression (LOESS) using a smoothing factor of 0.1 in order to achieve a robust calculation of these endpoints.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. All endpoints were compared between faster aspart and IAsp in a linear mixed model, with treatment and trial as fixed effects and subject as a random effect. Onset of appearance, t Early 50% Cmax, t max, t Late 50% Cmax, onset of action, t Early 50% GIRmax, t GIRmax and t Late 50% GIRmax were analysed on the linear scale. For these endpoints, least square means for each treatment, as well as treatment differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were estimated, and treatment ratios and 95% CIs were calculated using Fieller’s method [16]. AUCIAsp and AUCGIR endpoints, as well as C max and GIRmax, were log-transformed before analysis. For these endpoints, least square means for each treatment, as well as treatment ratios and 95% CIs, were estimated.

3 Results

3.1 Subjects

A total of 218 subjects were included in the pharmacokinetic analysis contributing with 261 insulin profiles for faster aspart and 256 insulin profiles for IAsp, while 119 subjects were included in the pharmacodynamic analysis contributing with 163 GIR profiles for faster aspart and 160 GIR profiles for IAsp. Baseline characteristics for each trial and for the pooled population are summarised in Online Resource 1, Table S2. Overall, for the pharmacokinetic analysis, the mean age of subjects was 36 years (range 18–63 years), the majority of subjects were male (70%), mean body weight was 75.6 kg (range 52.6–105.7 kg), and mean BMI was 24.1 kg/m2 (range 18.9–28.7). Mean duration of diabetes was 18 years (range 1–54 years), and mean HbA1c at baseline was 7.4% (57 mmol/mol) [range 4.7–9.2%; 28–77 mmol/mol]. Subjects contributing to the pharmacodynamic analysis had comparable baseline characteristics (Online Resource 1, Table S2).

3.2 Onset, Early Exposure and Early Glucose-Lowering Effect

The mean serum insulin concentration–time curve was shifted to the left for faster aspart compared with IAsp (Fig. 1a, c). Accordingly, a left-shift of the glucose-lowering effect profile was observed for faster aspart compared with IAsp (Fig. 1b, d).

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles following a subcutaneous dose of 0.2 U/kg faster aspart or IAsp in a pooled analysis of subjects with type 1 diabetes: mean serum IAsp concentration–time profiles for a 5 h and c 2 h after injection, and mean glucose-lowering effect profiles for b 5 h and d 2 h after injection. Mean pharmacokinetic profiles are based on 261 individual profiles for faster aspart and 256 individual profiles for IAsp, while mean pharmacodynamic profiles are based on 163 individual profiles for faster aspart and 160 individual profiles for IAsp. Variability bands show the standard error of the mean. IAsp insulin aspart

Overall, onset of exposure and onset of glucose-lowering effect for faster aspart versus IAsp were highly consistent between individual trials (Online Resource 1, Table S3). Based on the pooled analysis, onset of appearance occurred approximately 5 min earlier (i.e. twice as fast) and t Early 50% Cmax occurred approximately 10 min earlier (30% earlier) for faster aspart compared with IAsp (Table 1 and Online Resource 1, Table S4). Onset of action and t Early 50% GIRmax occurred approximately 5 min faster (23% faster) and approximately 10 min earlier (21% earlier), respectively, for faster aspart than for IAsp (Table 1 and Online Resource 1, Table S5). Both t max and tGIRmax also occurred earlier by 7 and 11 min, respectively, for faster aspart compared with IAsp (Table 1).

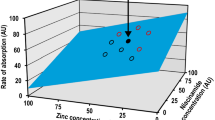

Greater early insulin exposure and early glucose-lowering effect with faster aspart versus IAsp were consistently observed across the individual trials (Figs. 2, 3). In the pooled analysis, both early insulin exposure and early glucose-lowering effect were greater for faster aspart than for IAsp within the first 2 h after injection. Within the first 30 min after injection, a two times greater insulin exposure (AUCIAsp,0–30 min) and a 74% greater glucose-lowering effect (AUCGIR,0–30 min) were seen with faster aspart than with IAsp.

Early exposure for faster aspart versus IAsp following a subcutaneous dose of 0.2 U/kg in subjects with type 1 diabetes in each of the trials and pooled. For the pooled analysis, exposure endpoints are based on 261 profiles for faster aspart and 256 profiles for IAsp. AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, IAsp insulin aspart

Early glucose-lowering effect for faster aspart versus IAsp following a subcutaneous dose of 0.2 U/kg in subjects with type 1 diabetes in each of the trials and pooled. For the pooled analysis, glucose-lowering effect endpoints are based on 163 profiles for faster aspart and 160 profiles for IAsp. AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, GIR glucose infusion rate, IAsp insulin aspart

3.3 Offset of Exposure and Glucose-Lowering Effect

The offset of insulin exposure occurred earlier for faster aspart than for IAsp, as t Late 50% Cmax was shorter for faster aspart than for IAsp (treatment difference faster aspart-IAsp [95% CI] −12.2 min [−17.9 to −6.5], p < 0.001) and AUCIAsp,2–t was smaller for faster aspart than for IAsp (treatment ratio faster aspart/IAsp [95% CI] 0.89 [0.85–0.93], p < 0.001) [Online Resource 1, Table S4]. Similarly, the offset of glucose-lowering effect occurred earlier for faster aspart than for IAsp, as shown from t Late 50% GIRmax (treatment difference −14.3 min [−22.1 to −6.5], p < 0.001) and AUCGIR,2–t (treatment ratio 0.90 [0.85–0.95], p < 0.001) [Online Resource 1, Table S5].

3.4 Overall Insulin Exposure and Glucose-Lowering Effect

AUCIAsp,0–t and C max were comparable between faster aspart and IAsp (treatment ratios faster aspart/IAsp [95% CI] 1.01 [0.98–1.04], p = 0.470; and 1.04 [1.00–1.08], p = 0.085, respectively) [Online Resource 1, Table S4]. Likewise, AUCGIR,0–t and GIRmax were both similar for faster aspart and IAsp (treatment ratios faster aspart/IAsp [95% CI] 0.98 [0.94–1.03], p = 0.426; and 1.01 [0.96–1.05], p = 0.814, respectively), suggesting total and maximum glucose-lowering effect for faster aspart and IAsp are comparable when both insulin products are administered at the same dose level (Online Resource 1, Table S5).

4 Discussion

In the current pooled analysis of clinical pharmacology trials in adult subjects with type 1 diabetes from the faster aspart clinical development programme, the main results were that faster aspart demonstrated a twice as fast onset of appearance and a two times higher early insulin exposure, and consequently a 74% greater glucose-lowering effect during the first 30 min after injection, compared with IAsp. Thus, compared with IAsp, faster aspart appears to better approximate the endogenous prandial insulin secretion in the healthy state.

The clinical implications of the 5 min earlier onset of appearance and the generally accelerated initial absorption of faster aspart compared with IAsp have been investigated in phase III trials comparing mealtime faster aspart and IAsp in subjects with type 1 and 2 diabetes treated for 26 weeks in a basal–bolus regimen [17, 18]. These trials have shown faster aspart provides better control of postprandial hyperglycaemia in a standardised meal-test compared with IAsp. In subjects with type 1 diabetes, faster aspart was superior to IAsp regarding change from baseline in 2-h postprandial glucose increment (treatment difference faster aspart-IAsp [95% CI] −0.67 mmol/L [−1.29 to −0.04]; −12.0 mg/dL [−23.3 to −0.7]; p = 0.0375), and a statistically significant difference in favour of faster aspart was seen regarding change from baseline in 1-h postprandial glucose increment (−1.18 mmol/L [−1.65 to −0.71]; −21.2 mg/dL [−29.7 to −12.8]; p < 0.0001) [17]. In subjects with type 2 diabetes, a more heterogeneous population than subjects with type 1 diabetes, superiority of faster aspart over IAsp could not be confirmed for the reduction from baseline in 2-h postprandial glucose increment as the difference in favour of faster aspart did not reach statistical significance (−0.36 mmol/L [−0.81 to 0.08]; −6.6 mg/dL [−14.5 to 1.4]; p = non-significant), while the reduction from baseline in 1-h postprandial glucose increment was statistically significantly greater for faster aspart than for IAsp (−0.59 mmol/L [−1.09 to −0.09]; −10.6 mg/dL [−19.6 to −1.7]; p = 0.0198) [18].

The best possible postprandial glucose control with current rapid-acting insulin analogues is achieved by injecting the insulin 15–30 min prior to meal initiation [19–21]. This injection–meal interval is introduced to counterbalance the delay from subcutaneous administration until insulin concentration in the circulation is high enough to process the carbohydrate load from the meal [7]. However, in daily life, due to convenience, many diabetes patients use no or only a relatively short injection–meal interval, which is in accordance with approved labelling [22, 23]. This may be particularly critical with higher glycaemic index meals, where a mismatch between rapid glucose absorption and the relatively delayed action of exogenous insulin results in initial postprandial hyperglycaemia, as discussed in a systematic review on the effects of dietary fat, protein and glycaemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1 diabetes and prandial insulin dosing strategies for these dietary factors [24]. The earlier onset of action and greater early glucose-lowering effect for faster aspart versus IAsp should help dosing at mealtime, in contrast to pre-meal dosing. Furthermore, it may provide the possibility for post-meal dosing when necessary in certain situations if an injection has been forgotten or if the size and/or composition of a meal cannot be estimated in advance, e.g. in toddlers or multimorbid geriatric patients. In the abovementioned phase III trial in subjects with type 1 diabetes, a treatment arm with a 20 min post-meal dosing of faster aspart was also included and showed an HbA1c reduction that was non-inferior to IAsp administered at mealtime, as well as similar rates of severe and confirmed hypoglycaemia versus mealtime IAsp [17]. Furthermore, in a meal-test the change from baseline in 2-h postprandial glucose increments did not differ statistically significantly between post-meal faster aspart and mealtime IAsp, while the increase from baseline in 1-h postprandial glucose increments was statistically significantly greater for post-meal faster aspart versus mealtime IAsp [17]. These results suggest the accelerated absorption of faster aspart versus IAsp may provide patients with the flexibility of dosing up to 20 min post-meal with no impact on overall glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia risk compared with IAsp administered at mealtime.

The present analysis showed faster aspart has an earlier offset of exposure and action compared with IAsp. The increased rate of offset may reduce the risk of late postprandial hypoglycaemia by avoiding that the glucose-lowering effect of the mealtime insulin lasts beyond the duration of glucose absorption after the meal [7]. On the other hand, a very fast offset of exposure might result in lack of circulating insulin in the late postprandial period and, consequently, the glucose-lowering effect does not last long enough to cover the glucose absorption from the meal, especially in the case of higher-fat meals [24]. Thus, a further accelerated absorption than seen with faster aspart could possibly lead to under-insulinisation in the late postprandial period and might therefore not be of clinical advantage. Importantly, for faster aspart, results from meal-test studies do not indicate that the rate of offset is too fast. Thus, plasma glucose for faster aspart was consistently lower than or equal to that for IAsp for up to 4–6 h post-meal in subjects with type 1 or type 2 diabetes [17, 18, 25].

The same general methodology was used in all six trials included in the current analysis, which qualified the approach to combine the trial results into a pooled analysis. The accelerated pharmacological properties of faster aspart compared with IAsp were consistently observed across the individual trials. Thus, all trials generally showed the same picture in terms of faster onset, greater early exposure and glucose-lowering effect and earlier offset for faster aspart relative to IAsp. The only difference between the individual trial results and the pooled results was the smaller CIs for the pooled analysis, which is an expected consequence of the substantially larger sample size.

Onset of action was defined as the time from trial product administration until the blood glucose concentration had decreased at least 0.3 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) from baseline. This definition may not reflect the exact time point of first insulin action but rather is a product of both onset and initial rate of action and thus may slightly overestimate the true onset of action [26]. Still, the strength of this definition is that onset of action can be accurately measured and is deemed valid for comparison between two insulin products. Furthermore, the currently used definition of onset of action is closer to the exact time point of first insulin action compared with previously used definitions such as t Early 50% GIRmax and time to reach 10% of AUCGIR [26, 27]. As such, the current definition may be regarded as having high clinical relevance. It should be recognised that using the decline in blood glucose concentration as a measure of onset of action compromises the basic concept of glucose clamping. The consequence is that with the current clamp design the very initial part of the GIR profile reflects the combined impact of increasing insulin action, as well as blood glucose concentration being below the glucose clamp target. However, this should not affect the comparison between faster aspart and IAsp as the same approach was used in all experiments. As a supplement to onset of action, onset of appearance can be appropriately used as this endpoint is estimated with high precision and the absolute value of onset of appearance is most likely closer to the real onset than the value obtained with any definition of onset of action.

It is inherently difficult to determine the end of action in a glucose clamp setting [28]. The classical definition of end of action, based on blood glucose escape to 8.3 mmol/L (150 mg/dL), will overestimate the end of action from a clinical perspective [28, 29]. At the same time, the exact point of last GIR above zero may be challenging to estimate and thus prone to some variability due to the small and erratic glucose infusion often needed during the last part of a glucose clamp [28]. Consequently, we chose offset of action as a measure of late glucose-lowering effect since this approach was assessed to provide the best combination of robustness and clinical relevance. In the present analysis, the endpoints t Late 50% GIRmax and AUCGIR,2–t were used to evaluate offset of action. Valid comparison of t Late 50% GIRmax between treatments requires no treatment differences for GIRmax [26], which was fulfilled in the current pooled analysis.

5 Conclusions

The accelerated pharmacological properties of faster aspart were consistent across all studies included in this pooled analysis of adult subjects with type 1 diabetes. The analysis demonstrated that faster aspart provides faster onset and greater early exposure and glucose-lowering effect, as well as earlier offset, compared with IAsp. Thus, faster aspart has the potential to more closely mimic the endogenous prandial insulin secretion pattern seen in healthy individuals and thereby to provide improved postprandial glucose control in patients with diabetes compared with currently available rapid-acting insulin analogues.

References

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86.

Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:405–12.

Woerle HJ, Neumann C, Zschau S, et al. Impact of fasting and postprandial glycemia on overall glycemic control in type 2 diabetes Importance of postprandial glycemia to achieve target HbA1c levels. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77:280–5.

Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients. Variations with increasing levels of HbA1c. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:881–5.

Mitrakou A, Kelley D, Mokan M. Role of reduced suppression of glucose production and diminished early insulin release in impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:22–9.

Heise T. Getting closer to physiologic insulin secretion. Clin Ther. 2007;29:S161–5.

Heinemann L, Muchmore DB. Ultrafast-acting insulins: state of the art. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:728–42.

Home PD. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rapid-acting insulin analogues and their clinical consequences. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:780–8.

Hermansen K, Bohl M, Schioldan AG. Insulin aspart in the management of diabetes mellitus: 15 years of clinical experience. Drugs. 2016;76:41–74.

US Food and Drug Administration. Inactive ingredient search for approved drug products. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/iig/index.cfm. Accessed 26 Jan 2017.

Buckley ST, Kildegaard J, Høiberg-Nielsen R, et al. Mechanistic analysis into the mode(s) of action of niacinamide in faster-acting insulin aspart. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(Suppl 1):A116–7.

Fath M, Danne T, Biester T, et al. Faster-acting insulin aspart provides faster onset and greater early exposure vs insulin aspart in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2017. doi:10.1111/pedi.12506.

Heise T, Stender-Petersen K, Hövelmann U, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of faster-acting insulin aspart versus insulin aspart across a clinically relevant dose range in subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clinical Pharmacokinet. 2016. doi:10.1007/s40262-016-0473-5.

Heise T, Hövelmann U, Zijlstra E, et al. A comparison of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties between faster-acting insulin aspart and insulin aspart in elderly subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(1):29–38.

Heise T, Hövelmann U, Brøndsted L, et al. Faster-acting insulin aspart: earlier onset of appearance and greater early pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects than insulin aspart. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:682–8.

Fieller EC. Some problems in interval estimation. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1954;16:175–85.

Russell-Jones D, Bode B, de Block C, et al. Double-blind mealtime faster-acting insulin aspart vs insulin aspart in basal–bolus improves glycemic control in T1D: the onset® 1 trial. Diabetes. 2016;65(Suppl. 1):A77.

Bowering K, Case C, Harvey J, et al. Faster-acting insulin aspart vs insulin aspart as part of basal-bolus therapy improves postprandial glycemic control in uncontrolled T2D in the double-blinded onset® 2 trial. Diabetes. 2016;65(Suppl. 1):A63.

Cobry E, McFann K, Messer L, et al. Timing of meal insulin boluses to achieve optimal postprandial glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:173–7.

Luijf YM, van Bon AC, Hoekstra JB, Devries JH. Premeal injection of rapid-acting insulin reduces postprandial glycemic excursions in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2152–5.

Howey DC, Bowsher RR, Brunelle RL, et al. [Lys(B28), Pro(B29)]-human insulin: effect of injection time on postprandial glycemia. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;58:459–69.

Overmann H, Heinemann L. Injection-meal interval: recommendations of diabetologists and how patients handle it. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999;43:137–42.

Jørgensen LN, Nielsen FS. Timing of pre-meal insulins in diabetic patients on a multiple daily injection regimen. A questionnaire study. Diabetologia. 1990;33(Suppl. 1):A116.

Bell KJ, Smart CE, Steil GM, Brand-Miller JC, King B, Wolpert HA. Impact of fat, protein, and glycemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1 diabetes: implications for intensive diabetes management in the continuous glucose monitoring era. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1008–15.

Heise T, Haahr H, Jensen L, et al. Faster-acting insulin aspart improves postprandial glycemia vs insulin aspart in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Diabetes. 2014;63(Suppl. 1):A34.

Jain L, Parks MH, Sahajwalla C. Determination of time to onset and rate of action of insulin products: importance and new approaches. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102:271–9.

Heise T, Nosek L, Spitzer H, et al. Insulin glulisine: a faster onset of action compared with insulin lispro. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:746–53.

Swinnen SG, Holleman F, DeVries JH. The interpretation of glucose clamp studies of long-acting insulin analogues: from physiology to marketing and back. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1790–5.

Lepore M, Pampanelli S, Fanelli C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of subcutaneous injection of long-acting human insulin analog glargine, NPH insulin, and ultralente human insulin and continuous subcutaneous infusion of insulin lispro. Diabetes. 2000;49:2142–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Henrik Jarlov, MD, Novo Nordisk A/S, for his review of, and input into, the manuscript, and Carsten Roepstorff, PhD, CR Pharma Consult, Copenhagen, Denmark, for providing medical writing support, which was funded by Novo Nordisk A/S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

This investigation was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Conflicts of interest

Tim Heise is shareholder of Profil, which has received research funds from Adocia, AstraZeneca, Becton–Dickinson, Biocon, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dance Biopharm, Eli Lilly, Grünenthal, Gulf Pharmaceutical Industries, Johnson & Johnson, Marvel, MedImmune, Medtronic, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi, Senseonics and Zealand Pharma. In addition, Tim Heise is member of advisory panels for Novo Nordisk and received speaker honoraria and travel grants from Eli Lilly, Mylan and Novo Nordisk. Thomas R. Pieber has received research support from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk, has served in advisory panels for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Roche Diabetes Care, and is an employee of CBmed—Center for Biomarker Research in Medicine. Thomas Danne has received research support from and/or has served in advisory panels for Abbott, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi and Ypsomed, and is a shareholder of DreaMed Diabetes. Lars Erichsen and Hanne Haahr are employees and shareholders of Novo Nordisk.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Heise, T., Pieber, T.R., Danne, T. et al. A Pooled Analysis of Clinical Pharmacology Trials Investigating the Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Characteristics of Fast-Acting Insulin Aspart in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Clin Pharmacokinet 56, 551–559 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0514-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0514-8