Abstract

The present review rationalizes the significance of the metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) interfaces in the field of photovoltaics and photocatalysis. This perspective considers the role of interface science in energy harvesting using organic photovoltaics (OPVs) and dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). These interfaces include large surface area junctions between photoelectrodes and dyes, the interlayer grain boundaries within the photoanodes, and the interfaces between photoactive layers and the top and bottom contacts. Controlling the collection and minimizing the trapping of charge carriers at these boundaries is crucial to overall power conversion efficiency of solar cells. Similarly, MOS photocatalysts exhibit strong variations in their photocatalytic activities as a function of band structure and surface states. Here, the MOS interface plays a vital role in the generation of OH radicals, which forms the basis of the photocatalytic processes. The physical chemistry and materials science of these MOS interfaces and their influence on device performance are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growing economies and increasing population demand more energy in the coming years. The prospect of global warming and limited fossil fuel reserves necessitates radical changes in our global energy production and consumption patterns. Primary supply of sustainable and eco-friendly energy is one of the major challenges of the twenty-first century. A recent report on 2030 Energy Outlook by BP points that an additional 1.3 billion people will grow into new energy consumers by 2030 [1]. Exxon’s 2040 Energy Outlook projects 85 % growth in global electricity demand during 2010–2040 [2]. Emerging non-OECD countries alone will experience a 150 % surge in electricity demand. However, to have such quanta of energy, the current energy growth of 1.6 % per year would require at least 35 years; therefore, a crisis is inevitable. This increased energy demand is one part of the story; the other part is depleting natural resources, increased production cost and high environmental concerns such as global warming due to excessive use of fossil fuels. Over 85 % of the primary supply in the present-day energy mix is contributed by fossil fuels, thereby putting the life sustenance at an increased risk in the planet [3]. To point out a consequence of increased energy production cost, many gas wells generate 80–95 % less gas after just 3 years contrary to the predictions that their lifetime would be 40 years. Given this swift weakening in natural gas production from newly drilled wells, it would be essential to drill 7200 wells per year at a cost of 42 billion dollars, to sustain the present level of natural gas production [4]. All these concerns focus our attention towards clean, sustainable, and zero cost sources of energy; i.e., the solar energy and its conversion into electrical energy as the most convenient for use in modern life. A total of 36,000 TW solar energy strikes the Earth. Assuming an efficiency of 25 %, a solar cell farm of area ~367 km × 367 km in the Sahara desert would meet the projected energy demand. For comparison, this area is only 0.3 % of 9.4 million km2 of the Sahara desert. Therefore, the sun could be a single solution to all our future energy needs [5–7].

Similarly, growing population has also increased the use of dyes in many industries such as textile, furniture, chemical and paint. The dumping or accidental discharge of dye wastewater has triggered a substantial amount of environmental and health problems, urging researchers globally to develop universal methods to treat dye wastewater efficiently. Until now, orthodox methods such as coagulation, microbial degradation, biosorption, incineration, absorption on activated carbon, filtration and sedimentation have been employed to treat dye wastewater [8, 9]. Recently, an approach called advanced oxidation process was developed to treat dye wastewater treatment [10]. This method involves the process of generating strong OH radicals for breaking down the complex molecules. Solar energy serves as the cheapest and efficient source of energy for generating these radicals through the process of photocatalysis. Thus, proper engineering and optimization of the materials can provide viable and efficient ways to harness this abundant resource for photovoltaic and photocatalytic applications.

Semiconductors, defined as materials with band gap energy ≤5 eV, are essential to absorb solar energy for enabling the above tasks; a multibillion dollar semiconductor industry is in operation with diverse types of semiconductors including elemental and compound semiconductors. Among them, metal oxide semiconductors (MOSs) represent a domain of relatively inexpensive and environmentally benign class of materials with a diverse range of properties owing to their rich structural diversity. Both natural and synthetic MOSs have diverse applications. The properties of MOS can be tailored in many ways, viz., varied choice of morphologies, introducing oxygen vacancies, doping, and so on.

In photovoltaics, MOSs serve as a scaffold layer for loading dyes in dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) and organic–inorganic hybrid perovskites in perovskite solar cells (PSCs), as well as electron and hole transport layers in DSSCs and organic solar cells (OSCs). The function of scaffold in DSSCs is to facilitate charge separation and charge transport, whereas that of the transport layers is to conduct one type of charge carrier block to the other type. Therefore, tailoring their properties is inevitable to develop high-performing photovoltaic devices using them. On the other hand, the electrochemical properties of the MOS such as band edge energies determine their success as photocatalysts.

This review emphasizes on the application of MOSs as electrodes and interfacial layers in the technologies that involve photon-assisted physiochemical processes. In Sect. 2, the role of MOSs in photovoltaics—dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) and organic solar cells (OSCs)—are discussed. The interfacial processes and energetics involved in the charge injection and extraction properties of these materials are elaborated. In Sect. 3, the effect of MOSs in photocatalytic systems is addressed focusing on dye degradation. Recent advances in photocatalysis involving plasmon/metal oxide interface is also discussed.

Photovoltaics

Recent advances in solar energy conversion technologies based on organic semiconductors as light-harvesting layer, such as dye-sensitized solar cells and organic solar cells, employ MOS nanostructures for efficient charge extraction and transportation between the electrodes and organic molecules. The transition MOSs are well known for their ability to exchange charges with condensed molecules, making them a viable and cost-effective candidate to be used in the photovoltaic devices.

Solar cells are classified into different schemes based either on the historical evolution or on their principles of operation. The class of solar cells based on a p–n junction is the first of its evolution and, therefore, are typically called first-generation solar cells [11, 12]. Semiconductors, either elemental such as Si or Ge or compounds such as GaAs or InP, are materials of choice to build p–n junction solar cells. Photoexcited carriers in the p–n junction are separated into mobile carriers by the built-in-electric field, or band bending, at the junction between the p- and the n-type semiconductors [12–14]. The photovoltage in the p–n junction is the difference in quasi-Fermi levels (i.e., the band bending) of n-type and p-type regions. A typical device consists of a 5 μm-long n-type semiconductor and 300 μm-long p-type ones, i.e., the minority carriers in the p–n junction are expected to travel ~300 μm for efficient charge collection, which requires rigorous control on their chemical purity [12, 15]. Requirement of such extreme purity of the semiconductors is one of the major cost limiters of the first-generation solar cells. The p–n junctions are typically built on single crystalline and polycrystalline platforms. The latter polycrystalline overcomes the cost limitations on chemical purity, however, at the expense of the photovoltaic conversion efficiency (PCE) [14, 16]. Whether or not a p–n junction is made from single or polycrystals, inherent limitations between the absorption and electron emission in those crystals put a theoretical limit on the photovoltaic conversion efficiency in p–n junction solar cells, known as a Schokely–Queisser limit. The Schokely–Queisser limit predicts a theoretical upper limit of 32 % PCE for single-junction (p–n) solar cells [12].

The second-generation solar cells are based on the charge separation at an interface either between two conjugated polymers or a fluorophore molecule conjugated with a metal oxide semiconductor. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at Colorado, USA, categorize them as “emerging solar cells” (Fig. 1). In the third generation, semiconducting nanocrystals of size in the quantum confinement region, known as quantum dots, is used as the light harvester [17]. The quantum dot offers the possibility of many photoelectrons per single absorbed photon of sufficient energy, thereby uplifting the theoretical conversion efficiency over 60 %. The first- and second-generation solar cells are collectively called ‘excitonic solar cells (ESCs).

In the ESCs, light absorption results in the generation of a transiently localized excited state, known as exciton—usually, a Frenkel type is formed. These Frenkel excitons cannot thermally dissociate into free carriers in the material in which it was formed. Moreover, excitons are the characteristics of semiconductor analogs to Fermi fluids in metals and are often characterized as a mobile excited state. An exciton can be considered as a quasi-particle with an electron in the conduction band (or lowest unoccupied molecular orbital, LUMO) and a hole in the valence band (or highest occupied molecular orbital, HOMO). When a semiconductor (molecule, crystals, or clusters) is anchored with another material whose conduction band (LUMO) lies at lower energy, then the exciton dissociates into mobile carriers (or free carriers) at the interface of the material system (Fig. 2). This process is the basis of ESCs. Examples of this type of ESCs include organic solar cells (OSCs), dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), and quantum dot solar cells. Conjugated polymers and/or organic materials such as PCBM, P3HT, etc., are the materials of choice in OSCs. In the DSSCs, a wide-band-gap MOS, such as TiO2, is anchored to a dye. In the third-generation quantum dot solar cells, quantum dots are used as light harvesters [18–20].

Although an upcoming energy technology, photovoltaics—the science and technology of solar cells—has steadily progressed. One may note that the p–n junction solar cells made from single crystals have reached a stage of performing with theoretical conversion efficiency. On the other hand, performance of “emerging solar cells” in the second and third generation is relatively inferior. Compared to the first-generation solar cells, these emerging solar cells offer ease of fabrication, flexibility, lower cost, and higher performance efficiency. Although p–n junction solar cells have the advantage of high PCE (>20 %) and long lifetime (25 years), ESCs have improved enormously in the past few years demonstrating PCEs as high as 12 % and lifetimes of 10 000 h [21–23].

Progress in photovoltaics has become indispensable to improve the performance and cost-effectiveness of harnessing the solar energy. As a function of this driving factor, intense research works are carried out across various components of a photovoltaic device. Among them, engineering the nanometer (electron) and micrometer (photon) scale interfaces among the crystalline domains is imperative for efficient charge transport, as these domains constitute the interfacial layers in the solar cells. The interfacial layers include the following: (1) inter-percolated high surface area junctions between photoelectron donors and acceptors, (2) the interlayer grain boundaries existing within the absorber material, and (3) the interfaces between the top and bottom contacts in conjunction with the photoactive layers. Optimizing the charge carrier transport across these interfaces is pivotal for the efficiency and lifetime of the photovoltaic device [24]. The existing challenges in the field of excitonic solar cells is represented in Fig. 3.

In this section, the application of MOSs in two main groups of solar technologies that are approaching or have exceeded 10 % solar power conversion efficiency are discussed, i.e., dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) and organic solar cells or organic photovoltaics (OPVs). Here, we also discuss the physical chemistry and materials science of these MOS interfaces and their impact on device performance.

Organic solar cells

Organic solar cells (OSCs) have attracted immense research interest in the past decade owing to easy fabrication and low cost [25]. The quest for improvement in power conversion efficiency (PCE) of OSCs has been actuated by the development of novel photoactive materials and device architectures [26–28]. Numerous donor–acceptor (D–A) polymers have been synthesized by varying the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) levels of the donor and the acceptor materials [27, 29–31]. The enhancement in short circuit currents (JSC) and open circuit voltages (VOC) achieved by means of band gap and interfacial engineering resulted in high PCE ~10 %. [25] Furthermore, development of novel printing and coating processes have been developed leading to roll-to-roll processing of organic solar cells [32–34]. During this course of development, transition metal oxide semiconductors (MOS) have gained profound attention in OSCs owing to their ability to transport/extract charge carriers efficiently and solution processibility which is well suited for roll-to-roll high-volume production.

Organic solar cells (OSCs) mostly employ bulk heterojunction (BHJ) device structure in which the photoactive blend comprises an electron-donating polymer and an electron-accepting fullerene derivative in a pattern of nanoscaled interpenetrating networks. Fabrication of ohmic contacts is very important in OSCs, but it is not as straightforward as that in inorganic solar cells. OSCs require specific materials for this purpose with appropriate interface engineering. Poor ohmic contacts with transparent conducting oxides (TCO) or metallic electrodes arise due to the (i) misalignment of energy levels or mismatched work function [35, 36], (ii) the formation of interfacial dipoles [37, 38] and (iii) interfacial trap states [39]. Various charge-extracting interlayers have been employed between the active layer and the electrodes to develop good and efficient ohmic contacts. Among the various interfacial materials used, transition metal oxide semiconductors (MOS) are considered as potential candidates owing to their high environmental stability, superior optical transparency and facile synthesis routes.

Open circuit voltage VOC of OSCs is determined by the energy-level alignment between the donor and the acceptor in devices with ohmic contacts; if not, it is determined by the work function difference of the contact electrodes [26, 40]. On the other hand, short circuit current (JSC) is determined by the amount of photogenerated carriers produced in the active layer upon illumination and the charge separation efficiency across the photoactive layer. Fill factor is determined by the factors such as series resistance, shunt resistance, and charge recombination/extraction rate in the device. Finally, the performance efficiency (PCE) is determined by the product of Voc, Jsc, and fill factor; which is then normalized to the incident light intensity usually 1 sun at AM 1.5 G [41]. Figure 4 shows the HOMO and LUMO levels of various donor polymers and acceptor fullerene derivatives along with the electron affinities and ionization energies of high or low-work-function MOS employed in OSCs [42]. These MOSs provide the basis for developing highly efficient and stable ohmic contacts by means of energy-level bending, vacuum-level shifting and Fermi-level pinning at the polymer–electrode interfaces. Furthermore, the use of oxide interlayers evades the direct contact between the photoactive layer and electrodes, where high densities of carrier traps or adverse interface dipoles hamper efficient charge collection. Moreover, MOS interfacial layers play a dominant role for developing ohmic contacts to maximize the VOC, because lower built-in potential eventually leads to an increase in dark current as well as carrier recombination.

Schematic view of the energy levels of metal oxides and orbital energies of some of the organic components used in OSCs. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref [47]. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society

Metal oxide semiconductors for OSCs

Metal oxide semiconductors (MOSs) for the OSCs can be p-type and n-type materials, contingent on the position of the conduction band and valence band. For an n-type material, electron transfer from the LUMO of the acceptor to the conduction band (CB) of the MOS is the requisite. For a p-type contact material, the valence band (VB) of the MOS is required to match the HOMO of the polymer. The wide band gap of the interface materials also serves as a barrier for carriers of the other sort, thus improving the carrier selectivity of the contacts [40, 43–47].

The main roles of interface materials are:

-

1.

To align/adjust the energetic barrier height between the photoactive layer and the adjacent electrodes.

-

2.

To materialize a selective contact for carriers of one sort (either holes or electrons).

-

3.

To control the polarity of the device (to make normal or inverted device structure) as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5 Schematic representation of a normal and b inverted device structure of OSCs [98]. Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies

-

4.

To prohibit a physical or chemical reaction between the polymer and electrode.

-

5.

To serve as an optical spacer.

Cathode interfacial layers for OSCs

Based on the device architecture (i.e., normal or inverted) as shown in Fig. 5, the cathode interfacial layer lies in conjunction with the low-work-function metal (top electrode) or at the bottom adjoining the TCO electrode. Initially, alkali metals or related compounds are used to make ohmic contacts to the electron acceptors in the bulk heterojunction/photoactive layer. Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) [48] and lithium fluoride (LiF) were used for this purpose owing to their low work function (<3.0 eV). They exhibited good electron injection properties and enhanced the VOC of the device effectively [49]. However, degradation issues such as oxidation of alkali metal compounds over a period of time leads to poor stability [50]. Therefore, the use of transition MOS such as ZnO and TiO2 with work functions corresponding to the LUMO levels of fullerenes is considered to be an effective alternative. These MOSs are well known for their chemical resistance to oxygen and moisture, optical transparency and solution processibility. Such characteristics make the n-type semiconducting oxides an effective alternative to low-work-function metals used as cathode contacts. The proficiency of these oxides is demonstrated in both conventional and inverted device geometries [51–56].

ZnO is presently the most widely used electron-transporting layer (ETL) in OSCs. Its Fermi level aligns well with the LUMO of electron acceptors [57]. Moreover, it also acts as an effective hole blocker owing to its high ionization potential, thereby increasing the shunt resistance of the device [55, 58]. ZnO is transparent to visible light and absorbs in the UV spectrum, serving as a low band filter for the photoactive layer. To fabricate OSCs with inverted device geometry, ZnO nanoparticles or colloids are spin coated onto TCO substrates. Solution-processed ZnO nanostructures are obtained from precursor solutions containing Zinc salts through methods such as sol–gel [59], solvothermal [60], or a hydrothermal process [61]. Moreover, ZnO NPs are readily synthesized from zinc acetate dehydrate and used as ETL [62–64]. Using such an approach, inverted poly (3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) cells with a PCE of 4 % have been demonstrated [65]. The synthesized ZnO nanostructures have a lot of defect states in them. The small diameter of the ZnO NPs possesses a large fraction of dangling bonds, giving rise to high density of gap states. Thus, elimination of localized energy states in the band gap of the charge transport layers in inverted organic solar cells significantly augments the operational stability of the device in addition to enhanced photovoltaic parameters. Therefore, UV exposure is required to improve the conductivity of ZnO NPs by means of photodoping and defect filling. UV-ozone (UVO) treatment was also found to passivate the surface defect states [57]. With this approach, PDTG-TPD:PC71BM-based devices with ZnO NPs as ETL exhibited enhanced device performance with PCE ~8 % [66]. However, this UV exposure method is not sufficient for optimum device performance. Another approach to achieve optimum device performance was by using in P3HT:PCBM-based devices by increasing the ZnO nanostructure crystallinity and annealing temperature. Altering the crystallinity by annealing the ZnO at two temperatures, viz. 160 and 240 °C, produced a difference in the density of localized energy states in the band gap of ZnO. The trap depth in the device annealed at 240 °C is lesser when compared with that annealed at 160 °C, as shown in Fig. 6 [67]. The devices fabricated using the ZnO nanostructures annealed at 240 °C showed remarkably higher power conversion efficiency (PCE) and IPCE values. The depth of electronic traps in the two devices was evaluated and the one with a higher crystallinity was characterized by a trap depth lower by a factor of two, when compared with the device annealed at lower temperature [67].

Trap depth (Δ) in devices A (160 °C) and B (240 °C) calculated from ln J vs 1/T curves. Inset shows the variation of trap depth (Δ) as a function of Φ [67]. Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies

Under the testing protocol ISOS-L-1, the devices A (annealed at 240 °C) and B (annealed at 160 °C) retained 64 and 48 % of their original efficiency after 400 h of constant illumination, respectively (refer Fig. 7) [67]. Moreover, ZnO nanowires were planted across the ZnO nanoparticles to increase the electron lifetime, decrease recombination, and improve charge collection at the corresponding electrodes. Reports have shown that incorporating electrospun ZnO nanowires could effectively increase the carrier lifetime by twofold [54].

Stability of the inverted devices with ZnO (ETL) and MoO3 (ETL) under constant illumination conditions tested under Protocol ISOS-L-1. a ZnO with low degree of localized states b ZnO interlayer with high degree of localized states or larger trap depth [57]. Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies

ZnO is also used to form the interconnecting unit in tandem OSCs. Such an interconnecting unit, basically a tunneling p–n junction, is sandwiched between the two BHJ cell stacks, thereby forming a hole–electron recombination zone [68]. In this zone, the Fermi levels of the HTL and the ETL are well matched to minimize the VOC loss in a tandem cell. Thus, ZnO is widely applied in OSCs for research and commercial purposes [68].

Similarly, TiO2 is also an n-type and wide gap semiconductor (Eg ~ 3.2 eV) with its conduction band minima composed of the Ti 3d band and its valence band maxima composed of the O 2p states [69–73]. In OSCs, TiOx films are usually processed by sol–gel process; therefore they are in amorphous phase rather than crystalline. The solution precursor is usually prepared using titanium isopropoxide along with solvent additives. TiOx films are typically deposited by spin coating at optimal speed followed by annealing up to ~150–200 °C, similar to the synthesis of sol–gel ZnO discussed in the previous section. OSCs fabricated with sol–gel TiOx films have been demonstrated in both conventional and inverted cells. In conventional cells, the incorporation of TiOx as an ETL exhibited enhanced JSC and FF when compared with devices using aluminum electrodes. OSCs fabricated with solution-processed TiOx films serving as ETL and PCDTBT:PC71BM blend as photoactive layer, results in PCE as high as 6 % [74].

The improvement of PCE was attributed to the improved electrical coupling with PC71BM and the improved light harvesting [75]. Here, TiO2 acts as an optical spacer providing more absorption cross section at the photoactive layer. TiO2 was also found to exhibit strong dependence on UV illumination [76, 77]. The UV-activated TiO2 films are shown to degrade much rapidly under continuous illumination during regular operating conditions. The UV light causes photodoping of TiO2 where oxygen is chemisorbed at those sites, leading to unfavorable band bending in the TiO2 and thereby hindering charge extraction [78]. UV photodoping is one of the prime issues to be solved to use it in OSCs as the ETL layer efficiently.

Metal oxide semiconductors (MOS) as anode interfacial layers

The primary requirement of an efficient MOS serving as HTL or anode interfacial layer is that its work function needs to be high as well as align with the HOMO level of the photoactive polymers [40, 46, 79]. The conjugated polymers with high ionization potential cannot form ohmic contacts directly in conjunction with the metal electrodes, because of the electron transfer from the metal to the organic photoactive layer. This electron transfer creates a dipole at the interface, leading to reduction in built-in potential of the device. The drop in built-in potential increases the series resistance and charge extraction field, thereby hindering the device performance. The energy level interaction at the MOS–organic interface is represented in Fig. 8 [80].

Energy level at oxide/organic interface. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [80]. Copyright 2012 Nature Publishing Group

Numerous vacuum-deposited transition MOS with high work functions, eminent optical transparency, and good stability have attracted significant research interest. OSCs incorporated with these MOSs have demonstrated good device performance. Most transition MOSs such as molybdenum oxide, tungsten oxide, and vanadium oxide are commonly used in n-type semiconductors for HTL. These MOSs enable effective Fermi-level pinning and also increase the built-in potential of the device. The role of these MOSs as HTL is discussed in the following section.

Molybdenum oxide (MoO3) has gained significant attention for improving device performance and stability in OSCs [81–84]. The MoO3 HTL reduces the charge recombination by suppressing the exciton quenching as well as the resistance at the photoactive layer/anode interface [85]. Besides, MoO3 HTL also serves as an optical spacer for improving light absorption, thereby enhancing the photocurrent [86–88]. Molybdenum oxide is widely used as hole injection material and was considered as a p-type semiconductor initially. Until recently, UPS studies have exposed that it is of n-type semiconductor and the charge transport occurs via the Fermi level being pinned with the valence band of the polymers. Moreover, vacuum-deposited/thermally evaporated MoO3 gives the advantage of precise thickness control in the nanoscale range of about 1–2 nm. Reports have revealed that the oxygen deficiency in e-MoO3 results in defect states in energy bands, which raises the Fermi level closer to the conduction band [89, 90].

However, MoO3 is highly sensitive to oxygen and moisture; even the trace amounts of oxygen in the nitrogen-filled glove box during device fabrication are shown to have detrimental effects on its electronic levels, imposing severe shortcomings in the device stability [91]. Upon exposure to ambient conditions (oxygen or air), the work function decreases to 5.3–5.7 eV, which is still adequate enough to form good ohmic contacts with organic hole transporting materials. Reports have indicated that further reduction of the suboxide results in the growth of gap states that would finally reach the Fermi energy, resulting in the metallic behavior of MoO2 [80, 92].

Generally, the hole transport in nanostructured MoO3 layer occurs via the shallow defect states present in its band gap formed as a result of oxygen vacancies [93–95]. These oxygen vacancies serve as n-type dopants and lead to Fermi-level pinning at the photoactive layer–MoO3 interface [96]. The mechanism of the charge transfer process across the MoO3 interlayer is represented in Fig. 9, which shows that the holes are extracted by injecting electrons into the HOMO of the donor (P3HT). Subsequently, the holes transferred to MoO3 hop to the Ag electrode through the shallow defect states generated by the oxygen vacancies [97].

Schematic showing the mechanism of hole transport across the molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) interlayer [97]. Reproduced by permission of the PCCP Owner Societies

Using MoO3 to replace PEDOT:PSS as the anode interfacial layer (HTL), the resulting devices show comparable initial performance with much enhanced stability as shown in Fig. 10, demonstrating that high-work-function n-type MOS can effectively replace PEDOT:PSS in both conventional and inverted devices [98].

Comparison between the normalized PCEs as a function of time for PCDTBT: PC71BM devices employing PEDOT:PSS and MoO3 as hole-transporting interfacial layers (HTL). Copyright © 2011 Wiley-VCH [98]

Reports have shown that a high degree of oxygen defects were introduced in the hole-conducting MoO3 layer by annealing the devices under vacuum (~10−5 mbar) at nominal temperature (120 °C) and time (10 min). The devices thus fabricated exhibited much higher operational stability, when tested following the ISOS-D-1 (shelf) protocol, than control devices annealed conventionally, i.e., in nitrogen atmosphere.

For large-scale production or R2R processing, it is necessary to deposit MoO3 by a solution-processing technique instead of vacuum deposition. Reports have shown that P3HT:PCBM cells with solution-processed MoO3 showed a PCE of 3.1 %. Despite the low-temperature process and acceptable PCE values, aggregation of s-MoOx is one of the major issues hindering its application in large-scale processing. However, the work function values of s-MoOx films tend to be lower than that of e-MoO3, thus affecting the quality of the resulting ohmic contacts. P3HT:PCBM-based devices are made with s-MoOx, as HTL exhibits a VOC of 0.55 V which is 50 mV lower than that of the devices made with e-MoO3. An investigation of better solution-processing conditions and methods is needed to make it commercially successful [45, 99, 100].

Another n-type MOS with high work function is tungsten oxide, WO3; similar to MoO3, its electronic structure is highly determined by its stoichiometry, its crystalline structure, and processing/deposition conditions. Evaporated films of amorphous WO3 are generally deficient in oxygen, which gives rise to the gap states and n-type semiconductivity. Thermally evaporated films of WO3 are typically oxygen deficient, thereby possessing a large amount of gap states. The oxygen deficiency also contributes to the n-type semiconductivity of WO3; therefore, its electrical properties like work function are also sensitive to oxygen exposure. The optical band gap of WO3 of thermally evaporated films is around 3.2–3.4 eV. Oxygen exposure is found to increase further up to 4.7 eV. Its performance as HTL is significantly acceptable as PEDOT:PSS, with the devices exhibiting VOC of 0.6 V and FF of 60 % [44, 101]. Reports have indicated that solution-processed tungsten oxide with a larger work function increased the efficiency to 3.4 % with JSC ~ 8.6 mAcm−2; VOC ~ 0.6 V; FF ~ 0.6 for a P3HT:PCBM cell. The devices exhibited an enhanced lifetime/stability by maintaining 90 % of the initial value after being exposed to ambient conditions for nearly 200 h without any encapsulation [102, 103]. These factors make s-WO3 a viable candidate than other solution-processed high-work-function oxides for application in large-scale coating in the R2R process.

Another n-type semiconducting oxide used as the anode interlayer is vanadium pentoxide, V2O5. Its band gap is around 2.8 eV as estimated by UPS and IPES studies [100], revealing that its absorption band partially covers the absorption band of PC71BM. Similar to MoO3 and WO3, the band structure of thermally evaporated V2O5 is highly sensitive to the ambient conditions. P3HT:PCBM devices fabricated using e-V2O5 (~10−6 Torr) as an anode interlayer exhibited an optimum PCE of ~3 %. Upon air exposure, the work function of e-V2O5 further reduces to 5.3 eV along with a significant reduction of electron affinity and increase of defect states. In comparison with MoO3, research on V2O5 is rudimentary. For a better understanding of the charge transport mechanism at the V2O5–polymer interface, additional investigations of the interface electronic structures are indispensable [43, 104, 105]. The inverted OSC devices fabricated with PCDTBT in the active layer along with TiO2 as the electron transport layer (ETL) and MoO3 as the hole transfer layer (HTL) exhibits high Voc of about 91 % with a PCE of 7.2 % as shown in Table 1, owing to low band gap of the polymer and efficient charge transport across the interface [98]. The devices that employ tungsten oxide (WO3) as HTL shows superior performance than vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) as HTL within the same P3HT-based active layer. The VOC of the WO3-based device shows significant improvement compared to that of the latter owing to reduced charge transport barrier at the interface and lower series resistance [106, 107]. Table 1 shows the photovoltaic parameters obtained for the inverted organic solar cells employing different photoactive layer and interfacial layers.

Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs)

O’Regan and Graetzel reported on the dye-sensitized solar cell (DSSC) established on the mechanism of novel regenerative photoelectrochemical processes with an efficiency of ~7.9 % [73]. Following its success, extensive research has been carried out in this field to increase the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of DSSCs by incorporating n-type MOSs such as TiO2, ZnO, Nb2O5, SrTiO3, and SnO2 and their composites as photoelectrode materials. The wide-band-gap MOSs (Eg > 3 eV) having suitable band position relative to dye (or photosensitizer) have been used for the fabrication of DSSCs. Owing to the wide band gap, the MOSs employed for the fabrication of DSSCs have absorption at the ultraviolet region. Therefore, photosensitizer/dye is responsible for the absorption of light at the visible and near-infrared region. Furthermore, the high surface area of nanoporous MOS increases dye loading; thereby enhancing light absorption leading to improved performance of DSSCs. In addition to the above-mentioned physical characteristics, low cost, natural abundance, and facile synthesis methods of MOS combined with facile solution processibility is another key advantage for the application in DSSCs [71, 112, 113].

Among the many wide-band-gap oxide semiconductors (TiO2, ZnO, and SnO2) that have been examined as potential electron acceptors for DSSCs, TiO2 is the most versatile. It delivers the highest efficiencies, is chemically stable, non-toxic, and available in large quantities. TiO2 has many crystalline forms, with anatase, rutile, and brookite being the most important ones. The crystal structure of anatase and rutile are based on a tetragonal symmetry, in which the Ti4+ atoms are sixfold coordinated to oxygen atoms. The main difference between both structures is the position of the oxygen atoms. In contrast to rutile, anatase has a smaller average distance between the Ti4+ atoms; thus, anatase is thermodynamically less stable. The phase transformation from anatase to rutile occurs in the temperature range of 700–1000 °C, depending on the crystallite size and impurities [69, 114, 115].

Rutile has slightly lower indirect band gap (3.0 eV) as compared to anatase (3.2 eV), which is attributed to a negative shift of the conduction band in anatase by 0.2 eV. The bonding within TiO2 is partly covalent and partly ionic. Therefore, stoichiometric crystals are insulating [71, 113]. However, a significant amount of trap states are induced during most synthesis routes, which are due to oxygen vacancies. These vacancies can also be formed reversibly under reduced pressure and/or elevated temperature, which can lead to a variation in conductivity by several orders of magnitude. The oxygen vacancies cause the formation of Ti3+ state, which dope the crystal negatively (n-type). In contrast to other semiconductors of similar band gaps (e.g., ZnO), it does not photodegrade upon excitation. On the other hand, TiO2 is less stable to UV degradation compared to tin oxide (SnO2), owing to its high band gap and high work function. However, low electron mobility (μn) through mesoporous TiO2 (~0.1 cm2 V−1 s−1) is a crucial issue and imposes severe limitations in enhancing the η of DSSCs closer to the theoretical limits. The energy levels of the conduction and valence bands of the MOS used in DSSCs are shown in Fig. 11. In the standard version of DSSCs, the typical film thickness is 2–15 µm, and the films are deposited using nano-sized particles of 10–30 nm. A double-layer structure can be fabricated, where an underlayer of thickness 2–4 µm is first deposited using larger (200–300 nm) size particles that acts as a light-scattering layer to induce a phototrapping effect [20, 69, 113, 114].

Band energies of conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) of different metal oxides used in DSSCs. Reprinted with permission from ref [72]. Copyright 2001 Nature Publishing Group

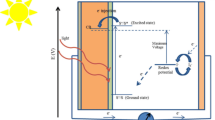

Dye-sensitized solar cells are based on an MOS nanostructure that is sensitized with a ruthenium-containing dye molecule. Different types of MOS photoanodes and their respective band energies are shown in Fig. 11. A redox electrolyte and two conducting glass substrates provide the connector to the external circuit. The functional principle is similar to photosynthesis: upon photoexcitation, the dye molecules inject an electron into the conduction band (EC) of TiO2, leaving the dye in its oxidized state (D+, also referred to as dye cation). The dye is restored back to its ground state by electron transfer from the redox pair [72]. The mechanism of operation of the DSSCs is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Schematic of the functional principle of a dye-sensitized solar cell. EVB and EC are the position of the valence and conduction bands of TiO2, respectively. The open circuit voltage VOC is defined by the difference between the Fermi-level EF and the redox potential EF,redox of the iodide/iodine couple. D*/D are the ground state and D+/D∗ is the excited state of the sensitizer from which electron injection into the TiO2 conduction band occurs

The regeneration of the sensitizer by iodide/tri-iodide electrolyte results in the recombination of the conduction band electron with the oxidized dye. Diffusion of e-through the nanocrystalline MOS film to the substrate electrode and diffusion of the oxidized redox species (I3− ions formed by oxidation of I−) through the electrolyte solution to the counter electrode facilitates both charge carriers to be transferred to the external circuit, where the energy is transferred to the external load and the regenerative cycle is completed by electron transfer to reduce I3− to I− [20, 71]. It is of critical importance for the functioning of the cell that the injection of electrons into the TiO2 is many orders of magnitude faster than any recombination (loss) of charge carriers. Moreover, the most important recombination process is the direct electron transfer from the conduction band of TiO2 to the redox electrolyte without passing the external circuit [71, 113].

Interfacial electron transfer is the process in which the excited electron from the LUMO of dye is injected into the conduction band of MOS (photoanode) with the rate constant k2 [113]. The kinetics of the interfacial electron transfer at the interface strongly relies on the energetics of the MOS/dye/electrolyte interface and the density of electrons in MOS photoanodes (i.e., Fermi-level of metal oxide). The interfacial electron transfer occurs mostly in a time scale of several picoseconds. Electron injection rate of >10−12s−1 has been reported for several sensitizers and MOS films [72, 112, 113].

Injected electron transfers across the mesoporous layer of MOS to the transparent conducting oxide (TCO). The efficacy of this process is mainly determined by the diffusion coefficient of electrons (De) and the electron lifetime (τe). Hence, the nanostructured MOSs with particle size greater than their exciton Bohr radius significantly influence the photoconversion efficiency of DSSCs. The factors that affect the DSSCs performance are (i) the mesoporous nature and high surface area of the MOS photoanodes, which allows large amount of dye anchoring resulting in the enhancement of the absorption cross section, and (ii) larger amount of density of states (DOS) in MOS than the molecular orbital of dye enables speedier injection of electrons from the dye molecule to the MOS. Considering the scenario, inefficient charge transport in the nanostructured MOSs originate from the trapping and detrapping of electrons at the surface atomic states in the electronic band. Moreover, the nanostructured MOS photoanodes consist of large amount of surface atoms resulting in greater degree of trap density. The trapping and detrapping process lowers the kinetic energy of the mobile electrons, eventually leading to poorer cell performance. Quantification of the traps and their subsequent elimination could improve the photovoltaic conversion efficiency of DSSCs beyond the present record of 11–15 % [69, 114–116].

However, low electron mobility (μn) through mesoporous TiO2 (~0.1 cm2V−1s−1) is a crucial issue and imposes severe limitations in enhancing the η of DSSCs closer to the theoretical limits [117]. One of the main hurdles due to inferior μn is the electron recombination with the electrolyte if the photoanode layer thickness is larger than the diffusion length, the transit length above which electrons are lost via recombination.

Tin oxide (SnO2) nanostructure, on the other hand, is a well-known transparent conducting oxide for nano-electronics due to high μn (10–125 cm2V−1s−1) and wider band gap (~3.6 eV) [118–121]. However, its conduction band minimum occurs at an energy lower than that of TiO2 [72] and, therefore, DSSCs with SnO2 electrode usually give low open circuit voltages (VOC ≤ 600 mV) [122]. Recently, VOC up to ~600 mV has been achieved by preparing the SnO2 core/shell electrodes and/or making composite electrode with other wide-band-gap semiconductors [123–125]. To increase the PCE of SnO2 based DSSCs, several approaches have been considered which includes: (i) modifying the electrode surface [126], (ii) modifying electrolyte composition [126, 127], (iii) combining with other MOS nanoparticles [125], and (iv) by using a core–shell configuration of suitable energy band-matched MOS [125, 128, 129].

Flower-shaped nanostructures of an archetypical transparent conducting oxide, SnO2, have been synthesized by an electrospinning technique as shown in Fig. 13. The flowers also exhibited an enhanced Fermi energy resulting in higher electron mobility [130]. Furthermore, DSSCs fabricated using the SnO2 flowers resulted in VOC ∼700 mV and one of the highest photoelectric conversion efficiencies achieved using pure SnO2. The study also demonstrated that the flowers are characterized by higher chemical capacitance, higher recombination resistance, and lower transport resistance compared with fibers. The effective electron diffusion coefficient and electron mobility in the flowers were an order of magnitude higher than that for the fibers (Fig. 14).

SEM images of SnO2 photoanodes: a fibers and b flowers [130]. Reproduced by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry

Schematic illustration of the fabrication method for a 3D host–passivation–guest dye-sensitized solar cell. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref [140]. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society

One of the most critical challenges in DSSCS research is the rapid recombination rate between the electrons in the conduction band of TiO2 and the oxidized redox mediator of the electrolytes. Advances in solid-state DSSCs with spiro-OMeTAD as HTM have shown that its usage is limited by the thickness of the photoanodes (~3 mm) due to incomplete percolation [131]. Therefore, pore filling has become an area of intense research to improve the hole injection dynamics and reduce the recombination rate with thickness [132, 133]. Several approaches have been investigated to improve the charge collection in liquid- and solid-state electrolytes by using one-dimensional ZnO and TiO2 nanostructures as photoanodes [134–137].

3D photoanodes for DSSCs was also developed to overcome such drawbacks. Recently, a novel bottom-up 3D host–passivation–guest (H–P–G) electrode was developed which enabled complete structural control of the nanostructure that favors efficient electron extraction and recombination dynamics with enhanced optical scattering properties for improved light harvesting. This 3D nanostructure when employed as photoanode in DSSCs significantly improved photocurrent, fill factor, and most importantly the photovoltage of the device. [114, 138–140]. DSSCs employing novel porphyrin sensitizers with cobalt (II/III)-based redox electrolyte exhibit high PCE >12 % as shown in Table 2 [141]. The specific molecular design of porphyrin sensitizers significantly retards the rate of interfacial back-electron transfer from the conduction band of the nanocrystalline titanium dioxide photoanode to the oxidized cobalt mediator, leading to the attainment of extraordinarily high photovoltage of about 1 volt [141]. Other similar DSSCs employing various dyes and redox shuttle mediators are listed in Table 2.

Photocatalysis

Photocatalysis is the key process that enables the conversion of solar energy into chemical energy needed for the decomposition of dyes or organic pollutants. The photocatalytic reactions usually occur on the surface of the semiconductors. Considering the scenario, metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) photocatalysts are employed as activators that assist in catalyzing the complex radical chain reaction involved in the photocatalytic oxidation processes. This technology is preferably used in photocatalytic dye degradation owing to advantages such as (1) low or no toxins, (2) being cheaper, (3) exhibiting tunable physiochemical properties by modifying the nanoparticle size and doping concentration and (4) good photocatalytic lifetime without undergoing substantial loss over a period of time. [145]. Generally, metal oxide photocatalysis is carried out via advanced oxidation process (AOP) which is performed by employing a strong oxidizing species of OH radicals usually produced in situ. The OH radicals form the trigger to initiate a sequence of reactions that crumbles the complex dye macromolecule into simpler and smaller, less harmful components [10, 146, 147].

Basic concept of photocatalysis

Photocatalytic reactions are basically a multi-step process involving oxidation and reduction reactions as illustrated in Fig. 15. The photocatalytic processes comprise three fundamental reaction pathways: (1) Photons are absorbed by the photocatalysts upon illumination from the light source. When the photons have higher energies greater than the band gap of the photocatalyst material, the electrons from the valence band (VB) are excited to the conduction band (CB) forming an electron–hole pair. (2) The photogenerated carriers (electrons and holes) have the tendency to recombine on the surface/bulk of the semiconductor. On the other hand, the electron–hole pairs may also get separated in a surface space charge region. If the diffusion of the electrons and holes is not hindered by any trap states or defect states, then the charge carriers would eventually reach the surface to trigger chemical reactions by charge transfer from the photocatalyst to an adsorbate. (3) Finally, the reduction reaction occurs when the photogenerated electrons interacts with the absorbed molecules on the semiconductor (photocatalysts) surface. To facilitate the electron transfer from the photocatalyst to the adsorbate, the conduction band (CB) minimum of the photocatalyst must be higher than the reduction potential of the adsorbate. Similarly, the photogenerated holes could generate strong oxidizing agents like OH radicals by interacting with the adsorbed molecules on the surface. Here, the valence band (VB) maximum of the photocatalyst must be lower than the oxidation potential of the adsorbate for efficient hole transfer [148–150].

Schematic diagram explaining the principle of photocatalysis. Reproduced from Ref. [155] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry

Material and electronic properties required for photocatalysts

The development of efficient photocatalysts for high chemical conversion efficiency solely relies on the means to suppress back-electron transfer or electron–hole pair recombination process. Therefore, the electron–hole pair generated can be efficiently used for the photocatalytic purpose, provided they exhibit the following properties: (i) the band gap or energy separation is sufficient or larger than the energy required for the desired reaction; (ii) the redox potentials of the electron and hole corresponding to their valence and conduction band are suitable for inducing redox processes; (iii) the reaction rates of the redox processes are faster than the electron–hole pair recombination rate [151].

Moreover, the additional bottleneck for solar energy conversion by photocatalysis is that most metal oxide-based photocatalyst materials are wide-band-gap semiconductors. Wide-band-gap semiconductors possess electronic band gaps around or larger than 3 eV and therefore their performance is confined to the small UV region of the solar spectrum. Therefore, the quest for finding efficient photocatalysts responsive to visible light took the limelight. Approaches such as doping or development of new materials suitable such as oxynitrides took the center stage [152–154]. One major drawback of employing dopants is that they often act as trap states serving as recombination centers and eventually resulting in performance degradation over a period of time. On the other hand, dye adsorption onto the photocatalyst surface is normally considered the second most essential component for photocatalytic dye degradation. One of the major factors that determines the dye adsorption onto the photocatalysts surfaces is the surface area [155].

From the electronic perspective, efficient diffusion of photoexcited charge carriers to the surface with less recombination is a basic requisite of any good photocatalyst. This process aids the development of specific surface sites to exhibit preferential oxidation or reduction chemical reactions. Several factors determine the efficacy of charge separation and direction selectivity of charge carriers, which include (i) band structure, (ii) polarization in case of ferroelectric materials, and (iii) electrostatic potentials in the surfaces as a function of charged adsorbate present on them [156–158]. Directed charge transport can also be facilitated by the electronic band bending present in the surface or near surface region of the photocatalysts. Upon photoexcitation, the band bending provides sufficient space charge region, assisting the charge separation of photogenerated carriers and also aiding the directional diffusion of the electrons to the surface; which in turn enhances the photocatalytic activity of the material. The extent of the space charge region is determined by the amount of doping and the dielectric constant of the material. Furthermore, the size of the catalyst particle also plays a major role in determining the band bending at the surface. The catalyst particle should be larger than the space charge layer, otherwise there would be no significant potential drop toward the surface. The width of the space charge layer Lsc depends on the materials properties and surface potential Vs, which in turn depends on the surface charges [159]:

where LD is the Debye length, K is Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature.

On the other hand, materials with high electric constant increase the width of the space charge region and hence it has a direct influence on the amount of photogenerated carriers extracted to the surface by means of the band bending or surface potential. It is noteworthy to mention that the band bending supports either holes or electrons transport to the surface depending on the direction of the potential, thereby the opposite charge carrier is trapped in the bulk of the material decreasing the photoactivity of the catalysts. Hence, it is very much and equally important to remove the oppositely charged carriers from the photocatalysts for efficient and stable long-term performance.

Titanium dioxide as photocatalysts

TiO2 is widely employed as a photocatalyst in dye wastewater treatment, mainly due to its capability to generate a highly oxidizing electron–hole pair. Moreover, it has good chemical stability, non-toxicity, and long-term photostability [160–162]. The wide band gap (Eg > 3.2 eV) of TiO2 limits its potential, because only high energy light in the UV region with wavelengths <387 nm can instigate the electron–hole separation process [156, 163]. Therefore, developing a photocatalyst that can efficiently harness the energy from natural sunlight, i.e., from the visible region, is one of the major challenges in this field [164]. Numerous modifications of the structure of TiO2 have been made to achieve the following: (i) decrease the band gap energy to harness the photons from the visible region; (ii) increase the efficiency of electron–hole production; and (iii) augment the absorbency of organic pollutants onto TiO2 by appropriate surface modifications [148, 149, 165]. Doping is one of the means to achieve the above-mentioned characteristics. Metal ions of noble metals (Pt, Pd, Ag, and Au) [166] and transition metals (Cr, Cu, Mn, Zn, Co, Fe, and Ni) [167] are used as dopants [168]. Even non-metals such as C, N, S, and P are used for this purpose [160, 161, 163, 169]. Transition metals are used as an alternative to noble metals to reduce the cost. Fe-doped TiO2 has been found to exhibit dye degradation efficiency of about 90 % [163].

The difference in photocatalytic activity between anatase and rutile TiO2

In general, anatase TiO2 usually exhibits higher photocatalytic activities than rutile TiO2 [170, 171]. The performance improvement arises from the fundamental difference in the electronic properties between them. Anatase TiO2 is an indirect band gap semiconductor, whereas rutile belongs to the direct band gap semiconductor. Anatase structure exhibits longer lifetime of photogenerated carriers (holes and electrons) than direct band gap rutile structure. The reason is that in anatase TiO2, the direct transitions of photogenerated electrons from the conduction band (CB) to valence band (VB) is not possible. Furthermore, anatase exhibits lower average effective mass of photogenerated electrons and holes when compared to rutile or brookite structure. The lower effective mass enables the rapid transport of photogenerated carriers from the interior to the surface of anatase TiO2, thereby resulting in lower recombination rate and eventually leading to higher photocatalytic activity than rutile structure. Moreover, the electron affinity of anatase is higher than rutile [172]. Therefore, photogenerated conduction electrons will flow from rutile to anatase and this factor is likely to be the driving force for the increased photoactivity of anatase–rutile composite materials [172]. Comparison of the recombination processes of photogenerated carriers within anatase and rutile structure is shown in Fig. 16.

Comparison of recombination processes of photogenerated carriers within a anatase and b rutile structure. Reproduced from Ref. [170] with permission from the PCCP Owner Societies

Zinc oxide as a photocatalyst

ZnO has a wide band gap (3.2 eV) and the unique electrical and optoelectronic property has made it a potential candidate as a photocatalyst. Studies have shown that the performance of ZnO under visible light is much more efficient than TiO2 [173–175]. Though it is highly effective under the influence of UV light [9, 176], with suitable physio-chemical modifications or by doping, ZnO can be used as a visible light photocatalyst. Apart from this, the usage of higher-intensity (500 W) visible light is found to increase the photocatalytic activity of the ZnO nanoparticles [177]. ZnO photocatalyst is also found to be better than SnO2, CdS and ZnS for dye degradation under UV and visible light [178]. Other MOSs such as vanadium oxide, tungsten oxide, molybdenum oxide, indium oxide, and cerium oxide have also been studied, but their performance is found to be inferior compared to titanium dioxide and zinc oxide [10, 179]. The performance of ZnO- and TiO2-based photocatalysts is listed comprehensively in Table 3.

Recent advances in photocatalysts: plasmon-assisted photocatalysis

As discussed earlier, the electron–hole separation is of paramount importance for realizing higher conversion efficiencies in photovoltaic and photocatalytic devices. Employing plasmonic technology for energy conversion is found to be a promising alternative to the conventional electron–hole separation in semiconductor devices. This technique involves generation of hot electrons in plasmonic nanostructures by means of electromagnetic decay of surface plasmons [187–190]. The working principle of the plasmonic energy conversion at the semiconductor interface is depicted in Fig. 17. When the metal nanoparticle (plasmon) is illuminated with highly energetic photons, hot electrons are generated in conditions of non-radiative decay. Hot electrons whose energies are sufficiently higher than the work function of the material get injected into the neighboring semiconductor, thereby producing a photocurrent. This interesting phenomenon caught the attention of the researchers and led to the development of NMNPs (noble metal nanoparticles)/semiconductor nanostructures as photocatalysts. Among the various structures thus produced with this combination, Au/TiO2 nanostructures show promising prospect, as the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect in these structures enhances the photoactivity of titania under visible light. In this process, the photogenerated electrons possess negative potential higher than that of the conduction band of the TiO2; thereby, the photogenerated electrons transfer efficiently from excited Au NPs to TiO2 NPs [189–191]. For instance, in the event of degradation of the pollutant 4-chlorophenol (4CP) using P-25 titania (commercial TiO2), the Au NPs significantly enhanced the catalytic activity by 80 % [192]. The photocatalytic mineralization of 4-CP exhibited by Au/TiO2 is higher than Pt/TiO2 > Ag/TiO2 > TiO2 [193]. Factors affecting the photocatalytic activity of the Au/TiO2 depend on numerous variables. The intensity of the SPR strongly relies on the shape of the Au and TiO2 NPs. Other factors include (i) dielectric constant of the surrounding medium, (ii) quantum mechanical/electronic interactions between the ligands (stabilizers) and the nanoparticles, and (iii) monodispersity of the NPs [194]. Au/TiO2 photocatalysts prepared by depositing pre-synthesized colloidal Au nanoparticles onto TiO2 nanocrystals of precisely controlled size and morphology through a delicately designed ligand-exchange method resulted in Au/TiO2 Schottky contact with low energetic charge transfer barrier. The photocatalysts thus obtained by this strategy showed superior activity compared to conventionally prepared photocatalysts in dye decomposition under visible-light illumination [195]. Figure 18 shows that the rate of decomposition of the dye is significantly higher than that of the commercial/pure TiO2 NPs. Thus, the mode of deposition of the Au and TiO2 NPs significantly affects the performance of the photocatalysts. Therefore, understanding the complex processes affecting the photocatalytic performance is indispensable for the rational design of the ideal noble metal-modified metal oxide semiconductor photocatalysts.

a Schematic showing the surface plasmon decay processes in which the localized surface plasmons undergoes radiative decay via re-emitted photons (left) or non-radiative decay via excitation of hot electrons (right). b Electrons from occupied energy levels are excited above the Fermi energy (Plasmonic energy conversion). c Hot electrons generated by the plasmons with sufficient energy to overcome the Schottky barrier (ϕSB = ϕM − χs) are injected into the conduction band of the adjacent semiconductor, where ϕM is the work function of the metal and χs is the electron affinity of the semiconductor. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [187]. Copyright 2014 Nature Publishing Group

a and b TEM images of the Au/TiO2 nanostructure. c Comparison of decomposition of MO dye by commercial TiO2 NPs (P25) and Au/TiO2 nanostructure prepared by different methods. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref [195]. Copyright (2014) American Chemical Society

Conclusion

In the future, the photovoltaic market depends not only on our ability to increase power conversion efficiencies, but also on the stability of the devices. Moreover, the photoanodes in DSSCs require high sintering temperature, limiting the substrate choice and device architectures. Hence to achieve high efficiency and cheaper solar technology, MOS, which is inexpensive and processable at low temperature, is preferred without compromising the light absorption and charge transport characteristics. Moreover, controlling the charge collection and minimizing the trapping of charge carriers at the interfacial boundaries are crucial to achieve high efficiency.

Similarly, the design of next-generation photocatalysts is needed to address the existing challenges in this field. Precise modification of oxide surfaces by surface engineering is known to exhibit better photoactivity. The development of unique surface phases and orientation could alter the electronic structure at the interfaces favoring efficient charge transport. Moreover, coating the oxide surfaces with additional monolayers could reduce surface recombination. Apart from that, exploiting the potentials of plasmons on the surface of metal oxide semiconductors via tuning the nanoparticle size and morphology, and appropriate selection of stabilizing ligands could improve the charge transfer at the plasmon/semiconductor interface. This approach could effectively enhance the photocatalytic activity and maintain the long-term photooxidation and photoreduction-processing sites selectively for greater efficiency.

References

Dudley, B.: The BP Energy Outlook 2030. Available: http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/about-bp/statistical-review-of-world-energy-2013/energy-outlook-2030.html. (2013)

Exxon: The outlook for energy: a view to 2040. Available: http://www.exxonmobil.com.sg/Corporate/energy_outlook_view.aspx. (2013)

Moss, R.H., Edmonds, J.A., Hibbard, K.A., Manning, M.R., Rose, S.K., van Vuuren, D.P., et al.: The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463, 747–756 (2010)

Hughes, J.D.: Energy: a reality check on the shale revolution. Nature 494, 307–308 (2013)

Hernández-Moro, J., Martínez-Duart, J., Guerrero-Lemus, R.: Main parameters influencing present solar electricity costs and their evolution (2012–2050). J Renew Sustain Energy 5, 023112 (2013)

Razykov, T.M., Ferekides, C.S., Morel, D., Stefanakos, E., Ullal, H.S., Upadhyaya, H.M.: Solar photovoltaic electricity: current status and future prospects. Sol. Energy 85, 1580–1608 (2011)

Norris, D.J., Aydil, E.S.: Materials science. Getting Moore from solar cells. Science New York NY 338, 625–626 (2012)

Rauf, M.A., Ashraf, S.S.: Radiation induced degradation of dyes—an overview. J Hazard. Mater. 166, 6–16 (2009)

Rao, A.N., Sivasankar, B., Sadasivam, V.: Kinetic studies on the photocatalytic degradation of Direct Yellow 12 in the presence of ZnO catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 306, 77–81 (2009)

Chan, S.H.S., Wu, T.Y., Juan, J.C., Teh, C.Y.: Recent developments of metal oxide semiconductors as photocatalysts in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) for treatment of dye waste-water. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 86, 1130–1158 (2011)

Fahrenbruch, A.L., Bube, R.H.: Heterojunction and heteroface structure cells. In: Fahrenbruch, A.L., Bube, R.H. (ed.) Fundamentals of solar cells, vol. 8, pp. 299–329 Academic Press (1983)

Green, M.A.: Solar cells: operating principles, technology, and system applications/Martin A Green. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall (1982)

Fahrenbruch, A. L., Bube, R. H.: Silicon solar cells. In: Fahrenbruch, A. L., Bube, R. H. (eds.) Fundamentals of solar cells, vol. 7, pp. 245–298. Academic Press (1983)

Fahrenbruch, A. L., Bube, R. H.: Polycrystalline thin films for solar cells. In: Fahrenbruch, A. L., Bube, R. H.Eds. (eds.) Fundamentals of solar cells, vol. 9, pp. 330–416. Academic Press (1983)

Green, M.A.: Thin film silicon solar cells/by Martin A Green. Energy Research and Development Corporation, Canberra (1996)

Fahrenbruch, A. L., Bube, R. H.: The CUXS/CDS solar cell. In: Fahrenbruch, A. L., Bube, R. H. (eds.) Fundamentals of solar cells, vol. 10, pp. 417–463, Academic Press (1983)

Green, M.A.: Third generation photovoltaics: advanced solar energy conversion/Martin A Green. Springer, Berlin; New York (2003)

Gregg, B.A.: Excitonic solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 4688–4698 (2003)

Hoppe, H., Sariciftci, N.S.: Morphology of polymer/fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 16, 45–61 (2006)

Hagfeldt, A., Boschloo, G., Sun, L., Kloo, L., Pettersson, H.: Dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6595–6663 (2010)

You, J., Dou, L., Yoshimura, K., Kato, T, Ohya, K., Moriarty, T., et al.: A polymer tandem solar cell with 10.6% power conversion efficiency. Nat Commun 4:1446 (2013)

Søndergaard, R.R., Hösel, M., Krebs, F.C.: Roll-to-Roll fabrication of large area functional organic materials. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 51, 16–34 (2013)

Roesch, R., Eberhardt, K.-R., Engmann, S., Gobsch, G., Hoppe, H.: Polymer solar cells with enhanced lifetime by improved electrode stability and sealing. Solar Energy Mater Solar Cells 117, 59–66 (2013)

Graetzel, M., Janssen, R.A.J., Mitzi, D.B., Sargent, E.H.: Materials interface engineering for solution-processed photovoltaics. Nature 488, 304–312 (2012)

R. F. Service: Outlook brightens for plastic solar cells. Science 332, 293 (2011)

Brabec, C.J., Sariciftci, N.S., Hummelen, J.C.: Plastic solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 11, 15–26 (2001)

Cai, W., Gong, X., Cao, Y.: Polymer solar cells: recent development and possible routes for improvement in the performance. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 94, 114–127 (2010)

Pivrikas, N.S.S.G.J.R.O.A.: A Review of Charge Transport and recombination in polymer/fullerene. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 15, 677–696 (2007)

Coakley, K.M., McGehee, M.D.: Conjugated polymer photovoltaic cells. Chem Mater 16, 4533–4542 (2004)

Krebs, F.C., Hösel, M., Corazza, M., Roth, B., Madsen, M.V., Gevorgyan, S.A., et al.: Freely available OPV-The fast way to progress. Energy Technology 1, 378–381 (2013)

Fung, D.D.S., Choy, W.C.H.: Organic solar cells. Springer, London (2013)

Rivière, G.A., Simon, J.-J., Escoubas, L., Vervisch, W., Pasquinelli, M.: Photo-electrical characterizations of plastic solar modules. Solar Energy Mater Solar Cells 102, 19–25 (2012)

Krebs, F.C.: Fabrication and processing of polymer solar cells: a review of printing and coating techniques. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 93, 394–412 (2009)

Krebs, F.C.: Polymer solar cell modules prepared using roll-to-roll methods: knife-over-edge coating, slot-die coating and screen printing. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 93, 465–475 (2009)

Park, Y., Choong, V., Gao, Y., Hsieh, B.R., Tang, C.W.: Work function of indium tin oxide transparent conductor measured by photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 68, 2699–2701 (1996)

Sugiyama, K., Ishii, H., Ouchi, Y., Seki, K.: Dependence of indium-tin-oxide work function on surface cleaning method as studied by ultraviolet and x-ray photoemission spectroscopies. J. Appl. Phys. 87, 295–298 (2000)

Hwang, J., Wan, A., Kahn, A.: Energetics of metal-organic interfaces: new experiments and assessment of the field. Mater Sci Eng R Rep 64, 1–31 (2009)

Hill, I.G., Milliron, D., Schwartz, J., Kahn, A.: Organic semiconductor interfaces: electronic structure and transport properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 166, 354–362 (2000)

Baldo, M.A., Forrest, S.R.: Interface-limited injection in amorphous organic semiconductors. Phy Rev B Conden Matter Mater Phy 64, 852011–8520117 (2001)

Steim, R., Kogler, F.R., Brabec, C.J.: Interface materials for organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 2499 (2010)

Steim, R., Kogler, F.R., Brabec, C.J.: Interface materials for organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 2499–2512 (2010)

Zhang, F., Xu, X., Tang, W., Zhang, J., Zhuo, Z., Wang, J., et al.: Recent development of the inverted configuration organic solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 95, 1785–1799 (2011)

Chen, S., Manders, J.R., Tsang, S.-W., So, F.: Metal oxides for interface engineering in polymer solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 24202 (2012)

Meyer, J., Hamwi, S., Kröger, M., Kowalsky, W., Riedl, T., Kahn, A.: Transition metal oxides for organic electronics: energetics, device physics and applications. Adv Mater Deerfield Beach Fla 24, 5408–5427 (2012)

Ratcliff, E.L., Zacher, B., Armstrong, N.R.: Selective interlayers and contacts in organic photovoltaic cells. Perspective 2, 1337–1350 (2011)

Po, R., Carbonera, C., Bernardi, A., Camaioni, N.: The role of buffer layers in polymer solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 285 (2011)

Ratcliff, E.L., Zacher, B., Armstrong, N.R.: Selective Interlayers and Contacts in Organic Photovoltaic Cells. J Phy Chem Lett 2, 1337–1350 (2011)

Huang, J., Xu, Z., Yang, Y.: Low-work-function surface formed by solution-processed and thermally deposited nanoscale layers of cesium carbonate. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 1966–1973 (2007)

Boix, P.P., Guerrero, A., Marchesi, L.F., Garcia-Belmonte, G., Bisquert, J.: Current-voltage characteristics of bulk heterojunction organic solar cells: connection between light and dark curves. Adv Energy Mater 1, 1073–1078 (2011)

Jørgensen, M., Norrman, K., Gevorgyan, S.A., Tromholt, T., Andreasen, B., Krebs, F.C.: Stability of polymer solar cells,”. Adv Mater Deerfield Beach Fla 24, 580–612 (2012)

Mbule, P.S., Kim, T.H., Kim, B.S., Swart, H.C., Ntwaeaborwa, O.M.: Effects of particle morphology of ZnO buffer layer on the performance of organic solar cell devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 112, 6–12 (2013)

Ibrahem, M.A., Wei, H.-Y., Tsai, M.-H., Ho, K.-C., Shyue, J.-J., Chu, C.W.: Solution-processed zinc oxide nanoparticles as interlayer materials for inverted organic solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 108, 156–163 (2013)

Elumalai, N. K., Vijila, C., Sridhar, A., Ramakrishna S.: Influence of trap depth on charge transport in inverted bulk heterojunction solar cells employing ZnO as electron transport layer. In: Nanoelectronics Conference (INEC), 2013 IEEE 5th International, pp. 346–349 (2013)

Elumalai, N. K., Jin, T. M., Chellappan, V., Jose, R., Palaniswamy, S. K., Jayaraman, S., et al.: Electrospun ZnO nanowire plantations in the electron transport layer for high efficiency inverted organic solar cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfac (2013)

Liang, Z., Zhang, Q., Wiranwetchayan, O., Xi, J., Yang, Z., Park, K., et al.: Effects of the morphology of a ZnO buffer layer on the photovoltaic performance of inverted polymer solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 2194–2201 (2012)

Manor, A., Katz, E.A., Tromholt, T., Krebs, F.C.: Electrical and photo-induced degradation of ZnO layers in organic photovoltaics. Adv Energy Mater 1, 836–843 (2011)

Chen, S., Small, C.E., Amb, C.M., Subbiah, J., Lai, T.H., Tsang, S.W., et al.: Inverted polymer solar cells with reduced interface recombination. Adv Energy Mater 2, 1333–1337 (2012)

Gonzalez-Valls, I., Lira-Cantu, M.: Vertically-aligned nanostructures of ZnO for excitonic solar cells: a review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2, 19 (2009)

Qian, L., Yang, J., Zhou, R., Tang, A., Zheng, Y., Tseng, T.K., et al.: Hybrid polymer-CdSe solar cells with a ZnO nanoparticle buffer layer for improved efficiency and lifetime. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 3814–3817 (2011)

Zhang, J., Sun, L., Yin, J., Su, H., Liao, C., Yan, C.: Control of ZnO morphology via a simple solution route. Chem. Mater. 14, 4172–4177 (2002)

Pacholski, C., Kornowski, A., Weller, H.: Self-assembly of ZnO: from nanodots to nanorods. Angew Chem Int Ed 41, 1188–1191 (2002)

Bahnemann, D.W., Kormann, C., Hoffmann, M.R.: Preparation and characterization of quantum size zinc oxide: a detailed spectroscopic study. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 3789–3798 (1987)

Beek, W.J.E., Wienk, M.M., Kemerink, M., Yang, X., Janssen, R.A.J.: Hybrid zinc oxide conjugated polymer bulk heterojunction solar cells. J Phy Chem B 109, 9505–9516 (2005)

Chu, T.Y., Tsang, S.W., Zhou, J., Verly, P.G., Lu, J., Beaupré, S., et al.: High-efficiency inverted solar cells based on a low bandgap polymer with excellent air stability. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 96, 155–159 (2012)

Chen, S., Choudhury, K.R., Subbiah, J., Amb, C.M., Reynolds, J.R., So, F.: Photo-carrier recombination in polymer solar cells based on P3HT and silole-based copolymer. Adv Energy Mater 1, 963–969 (2011)

Small, C.E., Chen, S., Subbiah, J., Amb, C.M., Tsang, S.W., Lai, T.H., et al.: High-efficiency inverted dithienogermole-thienopyrrolodione-based polymer solar cells. Nat. Photonics 6, 115–120 (2012)

Elumalai, N.K., Vijila, C., Jose, R., Ming, K.Z., Saha, A., Ramakrishna, S.: Simultaneous improvements in power conversion efficiency and operational stability of polymer solar cells by interfacial engineering. Phy Chem Chem Phy 15, 19057–19064 (2013)

Lee, D., Ki Bae, W., Park, I., Yoon, D.Y., Lee, S., Lee, C.: Transparent electrode with ZnO nanoparticles in tandem organic solar cells. Solar Energy Mater Solar Cells 95, 365–368 (2011)

Tétreault, N., Grätzel, M.: Novel nanostructures for next generation dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8506 (2012)

Ito, S., Zakeeruddin, S.M., Humphry-Baker, R., Liska, P., Charvet, R., Comte, P., et al.: High-efficiency organic-dye-sensitized solar cells controlled by nanocrystalline-TiO2 electrode thickness. Adv. Mater. 18, 1202–1205 (2006)

Grätzel, M.: Solar energy conversion by dye-sensitized photovoltaic cells. Inorg. Chem. 44, 6841–6851 (2005)

Grätzel, M.: Photoelectrochemical cells. Nature 414, 338–344 (2001)

O’Regan, B., Grätzel, M.: A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 353, 737–740 (1991)

Park, S.H., Roy, A., Beaupré, S., Cho, S., Coates, N., Moon, J.S., et al.: Bulk heterojunction solar cells with internal quantum efficiency approaching 100%. Nat. Photonics 3, 297–303 (2009)

Kim, J.Y., Kim, S.H., Lee, H.H., Lee, K., Ma, W., Gong, X., et al.: New architecture for high-efficiency polymer photovoltaic cells using solution-based titanium oxide as an optical spacer. Adv. Mater. 18, 572–576 (2006)

Steim, R., Choulis, S.A., Schilinsky, P., Brabec, C.J.: Interface modification for highly efficient organic photovoltaics. Appl Phy Lett 92, 093303 (2008)

Xue, H., Kong, X., Liu, Z., Liu, C., Zhou, J., Chen, W., et al.: TiO2 based metal-semiconductor-metal ultraviolet photodetectors. Appl Phy Lett 90, 1118 (2007)

Schmidt, H., Zilberberg, K., Schmale, S., Flügge, H., Riedl, T., Kowalsky, W.: Transient characteristics of inverted polymer solar cells using titaniumoxide interlayers. Appl Phy Lett 96, 243305 (2010)

Fortunato, E., Ginley, D., Hosono, H., Paine, D.C.: Transparent conducting oxides for photovoltaics. MRS Bull. 32, 242–247 (2007)

Greiner, M.T., Helander, M.G., Tang, W.M., Wang, Z.B., Qiu, J., Lu, Z.H.: Universal energy-level alignment of molecules on metal oxides. Nat. Mater. 11, 76–81 (2012)

Cheng, F., Fang, G., Fan, X., Liu, N., Sun, N., Qin, P., et al.: Enhancing the short-circuit current and efficiency of organic solar cells using MoO3 and CuPc as buffer layers. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 95, 2914–2919 (2011)

Kyaw, A.K.K., Sun, X.W., Jiang, C.Y., Lo, G.Q., Zhao, D.W., Kwong, D.L.: An inverted organic solar cell employing a sol-gel derived ZnO electron selective layer and thermal evaporated MoO3 hole selective layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 221107 (2008)

Lee, Y.-I., Youn, J.-H., Ryu, M.-S., Kim, J., Moon, H.-T., Jang, J.: Highly efficient inverted poly(3-hexylthiophene): methano-fullerene [6,6]-phenyl C71-butyric acid methyl ester bulk heterojunction solar cell with Cs2CO3 and MoO3. Org. Electron. 12, 353–357 (2011)

Kanai, Y., Matsushima, T., Murata, H.: Improvement of stability for organic solar cells by using molybdenum trioxide buffer layer. Thin Solid Films 518, 537–540 (2009)

Ding, H., Gao, Y., Kim, D.Y., Subbiah, J., So, F.: Energy level evolution of molybdenum trioxide interlayer between indium tin oxide and organic semiconductor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 073304 (2010)

Zhao, D.W., Liu, P., Sun, X.W., Tan, S.T., Ke, L., Kyaw, A.K.K.: An inverted organic solar cell with an ultrathin Ca electron-transporting layer and MoO[sub 3] hole-transporting layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 153304 (2009)

Zhao, D.W., Tan, S.T., Ke, L., Liu, P., Kyaw, A.K.K., Sun, X.W., et al.: Optimization of an inverted organic solar cell. Solar Energy Mater Solar Cells 94, 985–991 (2010)

Zhao, D.W., Tan, S.T., Ke, L., Liu, P., Kyaw, A.K.K., Sun, X.W., et al.: Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells Optimization of an inverted organic solar cell. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 94, 985–991 (2010)