Abstract

Concerning the global warming due to large CO2 emission, the efficient use of coal becomes important for getting sustainable energy production. Coal gasification under CO2-rich condition is expected to be an effective way to produce a concentrated and pressurized carbon dioxide stream, resulting in reduction in separation energy of CO2 for CCS. Moreover, the soot formation, which is of significant environmental concern, is still being neglected in the past studies of coal gasification. A one-step soot formation reaction mechanism is proposed in this study and implemented in numerical simulations of coal gasification with the aim of describing the gasification behaviors in a two-stage entrained-flow gasifier. In addition, the effects of O2 ratio and CO2 concentration on soot concentration, syngas heating value and carbon conversion are numerically studied in an effort to increase the syngas production. The Eulerian–Lagrangian approach is applied to solve the Navier–Stokes equation and the particle dynamics. Finite rate/eddy dissipation model is used to calculate the rate of nine homogeneous gas-to-gas phase reactions including soot formation and soot oxidation. While only finite rate is used for the heterogeneous solid-to-gas phase reactions. It is found that formation of soot enhances the H2 production in the gasifier. Carbon conversion gradually increases with an increase in O2 ratio, while producing a low heating value syngas beyond a certain limit of O2 ratio. In contrast, an increase in CO2 concentration in the gasifier increases heating value of product syngas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global energy consumption in 2030 is predicted to increase 1.4 times than that in 2007, where about half of the increase will be contributed by Asia. It is also predicted that remaining years of exploitable global energy resources in sequences are: coal (122 years), uranium (100 years), natural gas (60 years) and oil (42 years) [1]. Because of more exploitable coal resource compared to other resources, it is expected that coal will continue to play a significant role in meeting the future energy demand. However, due to use of fossil fuel mainly coal to generate power, large amounts of CO2 is discharged from conventional coal fired power plant, which is deemed as one of the major causes of global warming. Although technologies for employing renewable energy such as solar, wind, ocean, hydro, and biomass have been developed, the advantage of utilizing fossil fuels (mainly coal) for providing the most affordable electrical energy cannot be replaced overnight by any other technologies today [2]. However, clean coal technologies need to be implemented in the power sector in an effort to meet the environmental targets.

The clean coal technology field is moving in the direction of coal gasification with a second stage so as to produce a concentrated and pressurized carbon dioxide stream followed by carbon sequestration, including the capture and storage of carbon dioxides. However, CO2 concentration in the conventional coal–air combustion flue gas is too low for carbon sequestration to be considered economically feasible. Recycling CO2 in coal gasification process with the addition of oxygen will further increase CO2 concentration in the flue gas. Flue gases with CO2 concentration higher than 90 % can also be economically used for deep sea CO2 storage and enhanced oil recovery [3]. This technology has the potential to provide what may be called “zero emissions”—in reality, extremely low emissions of the conventional coal pollutants, and as low-as-engineered carbon dioxide emissions. This has come about as a result of the realization that efficiency improvements, together with the use of natural gas and renewable such as wind will not provide the deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions necessary to meet future national targets.

There are only few studies on coal gasification in two-stage entrained-flow gasifier found in World Wide Web. Moreover, no study on coal gasification under CO2-rich condition in two-stage entrained-flow gasifier is found. Chen et al. [4, 5] performed a series of numerical simulations under various operating conditions for a two-stage air blown entrained-flow gasifier. It was reported that increasing air ratio leads to increased CO2 and decreased CO and H2 concentrations, and accordingly, had a strong effect on the heating value of the product gas. The effect of air/coal partitioning to the two stages, and the feed rate of recycle char was found to be limited. Silaen et al. [6] conducted numerical simulation of coal gasification process inside a two-stage entrained-flow coal gasifier. They reported that smaller particles produced more CO and less CO2 which result in an increased syngas heating value. Luan et al. [2] studied the simulation of the coal combustion and gasification processes in a two-stage entrained-flow gasifier using the finite rate model for heterogeneous reactions. They reported that the increased O2/coal ratio leads to higher exit temperature and CO2 concentration, but lower CO concentration, resulting in a decrease of syngas heating value. However, the soot formation, which is of significant environmental concern, is still being neglected in the past studies of coal gasification [2, 4–6]. Soot formation has been observed in many pulverized coal utilization processes, including coal gasification and combustion. The formation of soot during coal gasification causes substantial heat losses due to radiative heat transfer. Therefore, an understanding of soot formation and its mechanism is necessary for the better design of coal gasification systems.

The main objectives of this study are to conduct numerical simulation including one-step soot formation mechanism in coal gasification and to discuss the effect of soot formation on the outcome of the simulation. In addition, a number of numerical simulations under O2-rich and CO2-rich gasification condition are carried out in an effort to increase the syngas production. The numerical results obtained from this study are considered to be an important step towards better designs of gasifiers.

Numerical methods

Computational domain

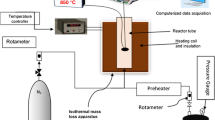

The coal gasifier (Fig. 1) considered here consists of a combustor stage and a reductor stage. Coal and char are injected into the combustor stage with O2-rich gas mixtures. The gasifier has two levels of injectors that are positioned axisymmetrically at combustor and reductor stage. The combustor injectors are placed similar to a tangential firing system to create swirling flow inside the gasifier. The reductor injectors are directed towards the center of the gasifier. The diameter of the coal/char inlet zone is <10 mm which is very small compared to the height of the gasifier (4.94 m). Thus, we make the mesh with various size ranges, from 2 to 10 mm. Moreover, making a uniform mesh with 2 mm size will significantly increase the computational time. A three-dimensional mesh consisting of 247,818 computational cells is used with the small cell size being around 2 mm and the largest one around 10 mm. The near wall y + value is 250, which is appropriate (30 > y + > 300) to apply the standard wall functions in the standard k–ε turbulence model.

Schematic of computational model adopted from CRIEPI [7]

Soot formation

Soot formation in coal gasification is a very complicated process. This is due to the fact that the molecules of coal volatiles, particularly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are much larger and more chemically diverse than those of simple hydrocarbon fuels. There are several soot models that have been proposed during the recent decades. Some of the most important empirical models are Khan and Greeves model [8], Tesner model [9] and Lindstedt model [10]. There are also some detailed models that take complex physical phenomena and detailed chemistry into account. One of the most comprehensive detailed models is that proposed by Frenklach [11]. A detailed kinetic model describing the formation and consumption of PAHs and soot in hydrocarbon combustion has also been developed by Richter et al. [12]. Although the detailed models have undergone remarkable development recently, these models are still computationally demanding and cannot be used for complex geometries. In our previous work [13], we investigated soot formation model in a plug flow reactor (PFR) and reported that the following two reactions are typically considered to be the main reaction path in soot formation: (a) particle nucleation—PAH of increasing size are mainly formed by sequence of chemical reactions between PAH and their radicals, and between PAH radicals. This process is repeated producing large PAHs that form soot particles [12, 13] and (b) soot/PAH oxidation—reaction of soot/PAH with oxygen/hydroxyl radicals that depletes PAH/soot [13]. Corresponding to these concepts, a one-step soot formation mechanism is proposed in the present study to investigate the effect of soot formation on product gas concentration and gas temperature in coal gasification. A schematic of soot formation mechanism is shown in Fig. 2. In the one-step soot formation mechanism, an aromatic hydrocarbon molecule benzene (C6H6) or naphthalene (C10H8) or phenanthrene (C14H10) or pyrene (C16H10) is considered as a precursor of soot formation. Before introducing the soot mechanism, the calculated results obtained using one-step soot formation mechanism are compared with those obtained using detailed soot formation mechanism under various gasification conditions [13].

Governing equations

For the fluid phase, the steady-state Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations as well as the mass and energy conservation equations are solved for two-stage entrained-flow coal gasifier shown in Fig. 1. The governing equations for the conservation of mass, momentum, energy and species in 3D Cartesian coordinates are given as follows:

Turbulent flows are characterized by fluctuating velocity fields. Turbulence models seek to solve a modified set of transport equations by introducing averaged and fluctuating components. In Reynolds averaging, the solution variables in the instantaneous Navier–Stokes equations are decomposed into the mean (time-averaged) and fluctuating components. For the velocity component:

where \( \overline{{u_{i} }} \) and \( u_{i}^{{\prime }} \) are the mean and fluctuating velocity components (i = 1, 2, 3). A standard k–ε model [14–16] is used to solve the turbulence. The turbulence kinetic energy, k, and its rate of dissipation, ε, are obtained from the following transport equations:

where G k represents the generation of turbulence kinetic energy related to the mean velocity gradient, and µ t is the turbulent viscosity. The turbulent model constants are C 1ε = 1.44, C 2ε = 1.92, C μ = 0.09, σ k = 1.0, and σ ε = 1.3 [15, 16].

The discrete ordinates (DO) radiation model is used to solve the radiative heat transfer equation. The DO radiation model considers the radiative transfer equation as:

In discrete phase modeling, pulverized coal particles are injected into the gasifier and tracked throughout the computational domain using a Lagrangian approach. The continuity and momentum of particles are expressed as follows:

F D(u–u p ) is the drag force per unit particle mass and F D is determined from

Re d is the relative Reynolds number based on the particle diameter and relative velocity.

The change of particle temperature during devolatilization is determined from the energy balance of particles governed by convective, latent heat and radiative heat transfer as follows [17, 18].

After the volatile species of the coal particle has evolved completely, char–O2, char–CO2 and char–H2O surface reactions begin. During surface reaction, the following heat balance equation is used:

Reaction models

When the temperature of the coal particles reaches the vaporization temperature (600 K), chemical reactions occur producing various amounts of gases, tar, and coke. The tar and gases are usually referred as volatiles. The volatiles are released according to Kobayashi model [19]. This model assumes two kinetic rates, k kin,1 and k kin,2, which may control the devolatilization over different temperature ranges, and yields an expression for the devolatilization as:

For the gas phase reactions including soot formation (R1–R9 shown in Table 1), the smaller of the two reaction rates (finite rate and eddy dissipation) is used as the overall reaction rate (\( \hat{R}_{i,k} \)). The finite rate and the eddy dissipation models consider the reaction rate as follows:

The burning rate of the carbon in coal particle is calculated using the finite rate model proposed by Smith [6, 23, 24]. The rates of depletion of carbon due to surface reactions (R10–R12 shown in Table 1) are given as:

The kinetic reaction rate k kin follows an Arrhenius expression as:

and the values of the kinetic parameters that are used to determine k kin for all reactions are also shown in Table 1.

Boundary conditions

Uniform distributions of inlet mass flow rate and temperature are given for all inlet boundary surfaces. The walls are assumed as stationary and smooth with no slip condition. A constant wall heat flux is assigned for wall boundary surfaces. The boundary condition of the discrete phase at walls is assigned as “reflect”, which means the discrete phase elastically rebound off once reaching the wall. At the outlet, the discrete phase exits the computational domain.

Numerical solutions procedure

Numerical methods

ANSYS FLUENT 12.0 is used to solve the set of equations discussed earlier. FLUENT uses a control volume-based technique to convert a general scalar transport equation to an algebraic equation that can be solved numerically. This control volume technique consists of integrating the transport equation about each control volume, yielding a discrete equation that expresses the conservation law on a control volume basis. General form of the discretized equation for an arbitrary control volume is as follows [16]:

where ϕ is scalar variable, \( \varGamma \) is diffusion co-efficient, and \( \vec{A} \) is surface area vector.

Spatial discretization

Solution of Eq. (21) results in values of scalar at each computational node. To calculate convection terms in Eq. (21), scalar values are required at cell surfaces which must be interpolated from cell-centroid values (nodes). First-order upwind scheme is used for spatial discretization of the convective terms. First-order upwind assumes the value of the variable throughout the cell and at the face to be the same as the centroid value.

Pressure–velocity coupling

The discretization of the equations governing the gas phase is solved by the SIMPLE algorithm for pressure–velocity coupling. The algorithm starts with an initial guess for variables in the system. Momentum equations are solved and pressure is corrected using a pressure correction equation. In the next step, all the other transport equations are solved and residuals are checked. If the solution is not converged, the current results would be used as an initial guess for the next iteration. This loop will continue until a converged solution is obtained.

Under-relaxation factor

The following equation is used during iteration to calculate new value of the variable in each cell based on its old value.

α is the under-relaxation factor and its value controls the change of variables in each iteration. Due to the nonlinearity of the equations, it is essential to reduce the change of variables in each time step; otherwise the solution becomes unstable and diverges.

Convergence criteria

For any transport equation, the discretized from of the equation has the following form:

where Zp and Znb are central and neighboring co-efficients, respectively. Imbalance of this equation is called residual and can be expressed as:

This equation will be scaled based on summation of residual in all computational cells. Usually, when the scaled residuals drop by three orders of magnitude, a qualitative convergence has been obtained. In this study, tolerances of pressure and velocity components are set to 1E-3, while tolerance of gas and solid components are set to 1E-5, and energy equation to 1E-6.

Calculation conditions

A bituminous-type CV coal (Coal Valley, Canada) is used to conduct the simulation of coal gasification. The proximate and ultimate analyses of coal are given in Table 2. The initial particle size distributions with a mean diameter of 60 μm are used in the calculation. The total mass inlet for experiment and calculation are kept same. The coal flow rates for combustor and reductor are set to 40 and 60 kg/h, respectively. The gas flow rates are adjusted in such a way that the inlet O2 ratio and O2 concentration become 0.528 and 23 wt%, respectively. The O2 ratio is defined here as the ratio of the amount of O2 fed into the gasifier to the amount of O2 required for complete combustion of carbon present in coal. During devolatilization, all hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen are assumed to be released as volatiles. Volatiles are considered as a single hypothetical component, Cα1Hα2Oα3Nα4. The values of α1, α2, α3 and α4 are calculated from the coal’s ultimate and proximate analyses. Once the volatile component is released, it is converted into CO, CO2, H2O, H2, CH4, C6H6 and N2 according to reaction R1. The pyrolysis data obtained from previous experimental work [26] are used to calculate the β values. In the calculation, all aliphatic and aromatic compounds are lumped into CH4 and C6H6, respectively (Table 3). Chen et al. [27] explained the gas evolution from rapid pyrolysis of a bituminous coal at various pyrolysis temperatures (500–900 °C). It was found that the ratio of CO to CO2 yield does not change with increasing the pyrolysis temperature. They also showed that the yield of higher hydrocarbon is approximately three times higher than that of CH4, which is very near to our previous works. Therefore, these two ratios (Y d,CO /Y d,CO2 = 1.27 and Y d,C6H6 /Y d,CH4 = 3.10) together with three elemental (C, H, O) mass balance equations are used to calculate the stoichiometric co-efficient (β) of product species for reaction R1 (see Table 3). Here Y d represents the mass yield for the corresponding species.

Results and discussion

Validation of one-step soot model

To validate the one-step soot model, a tubular-type reactor of 0.28 m diameter and 48 m length with the inlet gas velocity of 26.4 m/s is used to conduct the simulation. Eight overall gas phase reactions (R2–R9 shown in Table 1) are considered in the calculation. Benzene (C6H6), naphthalene (C10H8), phenanthrene (C14H10) and pyrene (C16H10) are independently considered as a precursor of soot formation. The calculated outlet species concentration of soot and syngas using the proposed soot model are compared with those reported in our previous paper [13] under various gasification conditions. The comparisons are shown in Fig. 3. The trends in outlet species concentration with increasing temperature are found to be similar, in both: detailed mechanism and overall gas phase reactions with proposed one-step soot mechanism. Soot concentration decreases with increasing the temperature while syngas concentration gradually increases. Soot formation as well as soot oxidation tends to increase at higher temperatures, resulting in an increase in CO and H2 concentration. A detailed explanation of the effect of temperature on soot and syngas concentration can also be found in Wijayanta et al. [13]. In addition, very similar results are obtained for various soot precursors (benzene, naphthalene, phenanthrene and pyrene) considered in the calculation. As increasing the molecular weight of species significantly increases the computational time, benzene is chosen as a soot precursor in the simulation of coal gasification in the two-stage entrained-flow gasifier shown in Fig. 1.

Comparison of calculated outlet soot and syngas concentration between detailed reaction mechanism [13] and overall gas phase reactions with one-step soot mechanism calculated at 2.0 MPa [open diamond is for benzene (C6H6), open circle is for naphthalene (C10H8), open triangle is for phenanthrene (C14H10) and multiply symbol is for pyrene (C16H10)]

Comparisons of species concentration and temperature profile

The comparison for two conditions of without soot and with soot shown in Fig. 4a indicates that there is a small change in outlet species concentration. An increase in H2 concentration under soot formation condition suggests that the concentration of H2 will be increased if the soot formation advances in the gasifier. This means that the formation of soot can increase the syngas heating value in this regard, despite having diverse effect of soot. Figure 4a also shows a comparison of outlet species concentration between experiment and calculation. Details of the experimental procedure and condition are described by Kidoguchi et al. [25]. A quite good agreement is obtained for main species CO, CO2 and H2. The agreement for the species H2O is not good due to the lack of information of experiment. A large deviation for H2O concentration between experiment and calculation is obtained due to the presence of some moisture in air during experiment which is ignored in the calculation.

Comparison between experiment [from CRIEPI, 25] and calculation: a outlet species concentrations and b gas temperature profiles at centerline

The gas temperature profiles at centerline for experiment and calculations are shown in Fig. 4b. In both, trends of gas temperature are found to be similar for experiment and calculations. However, calculation without soot formation overestimates the experimental gas temperature. In contrast, calculation with soot formation provides better agreement with the experiment. In case of soot formation, the reaction R1 includes aromatic species C6H6 which is considered as a soot precursor. C6H6 is then accumulated to produce a larger species, Coronene (C24H12), which is referred here as soot. The gas temperature for calculation with soot decreases significantly because of reducing the heat of reaction (R1). The gas temperature also decreases due to the large heat capacity of aromatic species considered in the soot formation reaction mechanism.

Effect of O2 ratio

The effect of O2 ratio on soot concentration, gas temperature, carbon conversion, etc., is numerically investigated under CO2-rich gasification condition (CO2 concentration = 14 wt%). The contours of soot concentration and gas temperature under conditions of two different O2 ratios at 0.528 and 0.7 are shown in Fig. 5a. A slight decrease in soot concentration at outlet from 1.79 to 1.73 wt% is observed if the O2 ratio increases from 0.528 to 0.7 in the gasifier. On the other hand, the gas temperature at outlet significantly increases from 1352 to 1588 K with increasing the O2 ratio. This is because under higher O2 ratio, exothermic char–O2 reaction tends to increase. The high gas temperature then advances the endothermic char–CO2 and char–H2O gasification reactions. This means increased O2 ratio significantly enhances char–O2 reaction as well char–CO2 and char–H2O reaction. Although, char–CO2 and char–H2O reactions are endothermic, the gas temperature increases due to significant rise in char–O2 oxidation reaction under higher O2 ratios. An increase in char–O2, char–CO2 and char–H2O reactions under a high O2 ratio at 0.7 results in an increase in carbon conversion and syngas concentration. Figure 5b shows that the carbon conversion gradually increases with increasing the O2 ratio and reaches a complete (100 wt%) conversion at a O2 ratio of 0.8. The soot concentration is also found to decrease at higher O2 ratios. In contrast, syngas heating value initially increases with increasing the O2 ratio, and reaches a maximum value of 3800 kJ/kg with 94 wt% carbon conversion at a O2 ratio of 0.7 (Fig. 5b). Beyond this value (O2 ratio = 0.7) heating value decreases with increasing O2 ratio because of shifting the environment from gasification towards combustion. Therefore, if the target is to get a complete conversion of carbon, a lower heating value gas will be produced from the coal gasification. Considering the carbon conversion in real gasification process where unconverted carbon is recycled as char and the use of more O2 where low heating value gas is produced, the O2 ratio exceeding 0.7 is not recommended for getting efficient coal gasification. Therefore, to improve the gasification efficiency, the concentrations of other gasification agents (CO2 and/or H2O) need to be increased in coal gasification process keeping O2 ratio under 0.7. With a target of reducing CO2 release into the atmosphere from coal gasification, the effect of CO2 concentration on soot concentration, syngas heating value and carbon conversion is numerically investigated in this study.

Effect of CO2 concentration

The effect CO2 concentration on soot concentration, gas temperature, carbon conversion, etc., is numerically investigated by changing the inlet concentration of CO2 at a constant O2 ratio (=0.528). The contours of soot concentration and gas temperature under conditions of two different CO2 concentrations at 14 and 50 wt% are shown in Fig. 6a. No significant difference in soot concentration is found for the two cases, although the gas temperature decreases with increasing the overall concentration of CO2. The gas temperature decreases with increasing the CO2 concentration due to increased char–CO2 reaction rate. Under CO2-rich concentration, endothermic reaction (backward reaction of R3) also increases, resulting in a decrease in gas temperature. The backward tendency of R3 on the other hand increases CO concentration and decreases H2 concentration. However, the syngas heating value gradually increases with increase of the CO2 concentration (shown in Fig. 6b) although H2 concentration decreases at higher CO2 concentrations. Soot concentration and carbon conversions for various cases are also shown in Fig. 6b. It is found that the soot concentration is nearly independent to CO2 concentration. On the other hand, the reductor carbon conversion gradually increases with increasing the CO2 concentration. A 15 % increase in carbon conversion of reductor coal is obtained if the inlet concentration of CO2 is increased from 14 to 50 wt%. However, the same change in CO2 concentration gives only a 1 % increase in overall carbon conversion. This is due to low carbon conversion of combustor coal at a high CO2 concentration (50 wt%). Interestingly, the syngas heating value increases from 2717 to 3501 kJ/kg which corresponds to a 28 % increase in syngas heating value. This indicates that the carbon conversion is not directly related to the syngas heating value. Under higher CO2 concentrations, char–CO2 (C + CO2 → 2CO) reaction dominates over char–O2 (C + 1/2O2 → CO) and char–H2O (C + H2O → CO + H2) reactions. This results in an increase in CO concentration with a small increase in carbon conversion. Therefore, it can be concluded that the production of syngas heating value per unit weight of carbon conversion will be higher if CO2 concentration increases in the gasifier.

Conclusions

A one-step soot formation mechanism is proposed and numerically validated with the detailed reaction mechanism. The proposed mechanism is used to conduct a series of 3D numerical simulation with the aim of describing the gasification process in two-stage entrained-flow gasifier. The calculated results with one-step soot formation reaction mechanism show a good agreement with the experimental results. It is found that formation of soot enhances the H2 production while predicting a low gas temperature in the gasifier. As the O2 ratio increases, soot concentration decreases while the gasifier gas temperature and carbon conversion increase. Beyond a certain limit of O2 ratio at 0.7, soot concentration and syngas heating value sharply decrease. In contrast, syngas heating value gradually increases as the CO2 concentration increases without affecting the soot concentration and with a small increase in overall carbon conversion. This means that the syngas heating value per unit weight of carbon conversion produced from CO2-rich gasification condition will be higher than that from the condition with lower CO2 concentrations and, therefore, coal gasification under CO2-rich condition can be efficiently implemented in IGCC system.

Abbreviations

- a :

-

Absorption co-efficient (m−1)

- a p :

-

Equivalent absorption co-efficient (m−1)

- A :

-

Surface area (m2)

- A f :

-

Pre-exponential factor (kg/m2 s Pa), (s−1)

- A R :

-

Magnussen constant for reactants (–)

- B P :

-

Magnussen constant for products (–)

- c p :

-

Specific heat of gas (J/kg K)

- C P :

-

Specific heat of coal particle (J/kg K)

- d :

-

Diameter (m)

- D k :

-

Diffusion co-efficient in kth reaction (m2/s)

- E :

-

Energy (J)

- E p :

-

Equivalent emission of coal particles (W/m3)

- f p :

-

Particle scattering factor (–)

- f w :

-

Fraction of water present in coal particles (–)

- f h :

-

Fraction of heat absorbed by coal particles (–)

- g :

-

Gravitational acceleration (m/s2)

- h :

-

Heat transfer co-efficient (W/m2 K)

- H :

-

Enthalpy (J/kg)

- H comb :

-

Height of combustor (m)

- I :

-

Number of species (–)

- I rad :

-

Radiation intensity (W/m2)

- I t :

-

Turbulent intensity (–)

- J i :

-

Mass flux of species i (kg/m2 s)

- k :

-

Turbulent kinetic energy (m2/s2)

- k kin :

-

Reaction rate constant (unit vary)

- K :

-

Number of reactions (–)

- L :

-

Latent heat of water present in coal (J/kg-coal)

- m :

-

Mass (kg)

- m p :

-

Mass of coal particle (kg)

- M i :

-

Molecular weight of species i (kg/kmol)

- N :

-

Order of reaction (–)

- p :

-

Pressure (Pa)

- \( \vec{r} \) :

-

Position vector (m)

- R :

-

Universal gas constant (8.314 × 103) (J/kmol K)

- R i :

-

Source of chemical species i due to reaction (kg/m3 s)

- \( \hat{R}_{i,k}^{(A)} \) :

-

Rate of production (Arrhenius) of species i in kth reaction (kmol/m3 s)

- \( \hat{R}_{i,k}^{(R)} \) :

-

Rate of production (Eddy dissipation) of reactant i in kth reaction (kmol/m3 s)

- \( \hat{R}_{i,k}^{(P)} \) :

-

Rate of production (Eddy dissipation) of product i in kth reaction (kmol/m3 s)

- \( \bar{R}_{k} \) :

-

Rate of particle surface species depletion in kth reaction (kg/s)

- \( \tilde{R}_{k} \) :

-

Rate of particle surface species reaction per unit area in kth reaction (kg/m2 s)

- Re d :

-

Reynolds number based on the particle diameter (–)

- s :

-

Path length (m)

- \( \vec{s} \) :

-

Direction vector (m)

- S m :

-

Rate of mass added from coal particle (kg/m2 s)

- S h,reac :

-

Source of heat due to reaction (W/m2 s)

- t :

-

Time (s)

- T :

-

Temperature (K)

- u, v, w :

-

Velocity magnitude (m/s)

- \( \vec{v} \) :

-

Velocity vector (m/s)

- \( \overline{{u_{i} }} \) :

-

Mean velocity component

- \( u_{i}^{{\prime }} \) :

-

Fluctuating velocity component

- V :

-

Volume (m3)

- X i :

-

Molar concentration of species i (kmol/m3)

- y + :

-

Distance (–)

- Y i :

-

Mass fraction of species i (–)

- z :

-

Height of reactor (m)

- α 1 :

-

Yield parameter for first step devolatilization (–)

- α 2 :

-

Yield parameter for second step devolatilization (–)

- ε :

-

Turbulent dissipation rate (m2/s3)

- ε p :

-

Emissivity of coal particle (–)

- \( \eta^{{\prime }} \), \( \eta^{{\prime \prime }} \) :

-

Rate exponent for reactants, products (–)

- \( \nu^{{\prime }} \), \( \nu^{{\prime \prime }} \) :

-

Stoichiometric co-efficient for reactants, products (–)

- \( \theta_{\text{R}} \) :

-

Radiation temperature (K)

- μ :

-

Dynamic viscosity (Pa s)

- μ t :

-

Turbulent viscosity (Pa s)

- ρ :

-

Density (kg/m3)

- σ :

-

Stefan–Boltzmann constant (5.669 × 10−8) (W/m2 K4)

- \( \sigma_{k} \) :

-

Turbulent Prandtl number for k (–)

- \( \sigma_{\varepsilon } \) :

-

Turbulent Prandtl number for ε (–)

- σ s :

-

Scattering co-efficient (m−1)

- σ p :

-

Equivalent particle scattering factor (m−1)

- \( \varOmega \) :

-

Solid angle (°)

- a:

-

Ash

- ac:

-

Activation

- b:

-

Backward

- f:

-

Forward

- i:

-

Species

- h:

-

Heat

- m:

-

Mass

- P:

-

Product species

- p:

-

Particles

- R:

-

Reactant species

- rad:

-

Radiation

- t:

-

Turbulent

- 0:

-

Initial stage

References

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Energy in Japan 2010, Japan 13–14 (2010)

Luan, Y.T., Chyou, Y.P., Wang, T.: Numerical analysis of gasification performance via finite-rate model in a cross-type two-stage gasifier. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 57, 558–566 (2013)

Hao, L., Ramlan, Z., Bernard, M.G.: Comparisons of pulverized coal combustion in air and in mixtures of O2/CO2. Fuel 84, 833–840 (2005)

Chen, C., Masayuki, H., Toshinori, K.: Numerical simulation of entrained-flow coal gasifiers part I: modeling of coal gasification in an entrained-flow gasifier. Chem. Eng. Sci. 55, 3861–3874 (2000)

Chen, C., Masayuki, H., Toshinori, K.: Numerical simulation of entrained-flow coal gasifiers part II: effects of operating conditions on gasifier performance. Chem. Eng. Sci. 55, 3875–3883 (2000)

Silaen, A., Wang, T.: Effect of turbulence and devolatilization models on coal gasification simulation in an entrained-flow gasifier. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 53, 2074–2091 (2010)

Hara, S., Oki, Y., Kajitani, S., Watanabe, H., Umemoto, S.: Examination of gasification characteristics of pressurized two-stage entrained-flow coal gasifier—influence of oxygen concentration in gasifying agent. CRIEPI Energy Engineering Research Laboratory Report No. M08019 (2009)

Khan, I.M., Greeves, G.: A method for calculating the formation and combustion of soot in diesel engines. In: Afghan, N.H., Beer, J.M. (eds.) Heat transfer in flames, pp. 389–404. Scripta, Washington DC (1974)

Tesner, P.A., Snegiriova, T.D., Knorre, V.G.: Kinetics of dispersed carbon formation. Combust. Flame 17, 253–260 (1971)

Leung, K.M., Lindstedt, R.P., Jones, W.P.: A simplified reaction mechanism for soot formation in nonpremixed flames. Combust. Flame 87, 289–305 (1991)

Appel, J., Bockhorn, H., Frenklach, M.: Kinetic modeling of soot formation with detailed chemistry and physics: laminar premixed flames of C2 hydrocarbons. Combust. Flame 121, 122–136 (2000)

Richter, H., Granata, S., Green, W.H., Howard, J.B.: Detailed modeling of PAH and soot formation in a laminar premixed benzene/oxygen/argon low-pressure flame. Proc. Combust. Inst. 30, 1397–1405 (2005)

Wijayanta, A.T., Alam, M.S., Nakaso, K., Fukai, J.: Numerical investigation on combustion of coal volatiles under various O2/CO2 mixtures using a detailed mechanism with soot formation. Fuel 93, 670–676 (2012)

Jovanovic, R., Milewska, A., Swiatkowski, B., Goanta, A., Spliethoff, H.: Numerical investigation of influence of homogeneous/heterogeneous ignition/combustion mechanisms on ignition point position during pulverized coal combustion in oxygen enriched and recycled flue gases atmosphere. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 54, 921–931 (2011)

Launder, B.E., Spalding, D.B.: The numerical computation of turbulent flows. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 3, 269–289 (1974)

Ansys Fluent 12.0 User’s Guide, Ansys Inc., (2009)

Viskanta, R., Menguc, M.P.: Radiation heat transfer in combustion systems. Progress Energy Combust. Sci. 13, 97–160 (1987)

Hossain, M., Jones, J.C., Malalasekera, W.: Modelling of a bluff-body nonpremixed flame using a coupled radiation/flamelet combustion model. Flow Turbul. Combust. 67, 217–234 (2001)

Kobayashi, H., Howard, J.B., Sarofim, A.F.: Coal devolatilization at high temperatures. Symp. (Int.) Combust. 16, 411–425 (1977)

Hashimoto, N., Kurose, R., Shirai, H.: Numerical simulation of pulverized coal jet flame employing the TDP model. Fuel 97, 277–287 (2012)

Watanabe, H., Otaka, M.: Numerical simulation of coal gasification in entrained-flow coal gasifier. Fuel 85, 1935–1943 (2006)

Massachusetts Ins. of Tech., Combustion Research Website. (http://web.mit.edu)

Kazakov, A., Wang, H., Frenklach, M.: Detailed modeling of soot formation in laminar premixed ethylene flames at a pressure of 10 bar. Combust. Flame 100, 111–120 (1995)

Smith, I.W.: The combustion rates of coal chars: a review. Symp. (Int.) Combust. 19, 1045–1065 (1982)

Kidoguchi, K., Kajitani, S., Oki, Y., Umemoto, S., Umetsu, H., Hamada H., Hara, S.: Evaluation of CO2 enriched gasification characteristics using 3t/d bench scale coal gasifier—influence of CO2 concentration in gasifying agent. CRIEPI Energy Engineering Research Laboratory Report No. M11019 (2012)

Alam, M.S., Agung, T.W., Nakaso, K., Fukai, J., Norinaga, K., Hayashi, J.: A reduced mechanism for primary reactions of coal volatiles in a plug flow reactor. Combust. Theor. Model. 14(6), 841–853 (2010)

Chen, L., Zeng, C., Guo, X., Mao, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, W., Long, Y., Zhu, H.: Gas evolution kinetics of two coal samples during rapid pyrolysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 91, 848–852 (2010)

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by NEDO project under Innovative Zero-emission Coal Gasification Power Generation Project and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24.6161. The authors also acknowledge the GCOE, Novel Carbon Resource Sciences, Kyushu University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Saiful Alam, M., Wijayanta, A.T., Nakaso, K. et al. Study on coal gasification with soot formation in two-stage entrained-flow gasifier. Int J Energy Environ Eng 6, 255–265 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40095-015-0173-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40095-015-0173-1