Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to ascertain vital status of patients considered lost to follow-up at an HIV clinic in Guinea-Bissau, and describe reasons for loss to follow-up (LTFU).

Methods

This study was a cross-sectional sample of a prospective cohort, carried out between May 15, 2013, and January 31, 2014. Patients lost to follow-up, who lived within the area of the Bandim Health Project, a demographic surveillance site (DSS), were eligible for inclusion. Active follow-up was attempted by telephone and tracing by a field assistant. Semi-structured interviews were done face to face or by phone by a field assistant and patients were asked why they had not shown up for the scheduled appointment. Patients were included by date of HIV testing and risk factors for LTFU were assessed using Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

Among 561 patients (69.5 % HIV-1, 18.0 % HIV-2 and 12.6 % HIV-1/2) living within the DSS, 292 patients had been lost to follow-up and were, therefore, eligible for active follow-up. Vital status was ascertained in 65.9 % of eligible patients and 42.7 % were alive, while 23.2 % had died. Information on reasons for LTFU existed for 103 patients. Major reasons were moving (29.1 %), travelling (17.5 %), and transferring to other clinics (11.7 %).

Conclusion

A large proportion of the patients at the clinic were lost to follow-up. The main reason for this was found to be the geographic mobility of the population in Guinea-Bissau.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a major problem in low-income countries and sub-Saharan Africa is heavily affected, with 69 % of all HIV infected people in the world living here [1]. Antiretroviral treatment (ART) improves the survival of HIV infected individuals and is an important component, when attempting to prevent the spread of infection [2–6]. Due to joined efforts of national health authorities and global actors, such as the World Health Organization and United Nations, Africa has experienced an increased ART coverage and a subsequent reduction in the number of newly infected people. West Africa has also experienced progress in HIV care, but by the end of 2012 less than half of the people eligible actually received ART, and in all measures this region tends to lack behind Eastern and Southern Africa. The difficulties and challenges, that HIV programs experience, vary between countries but strong political support, robust funding, solid planning and technical guidance are important factors for successful scale up of ART [1].

Despite the decreasing incidence of HIV-1 in Africa the number of new HIV infections appears to be increasing in the West African country Guinea-Bissau [7, 8]. There are no nationwide surveys on the HIV prevalence in Guinea-Bissau but UNAIDS estimates that 3.9 % of all adults in the country are HIV infected [9]. In 1996 and 2006 HIV prevalence studies were conducted in Bissau, the capital of Guinea-Bissau showing a declining HIV-2 prevalence from 7.4 to 4.4 % but an increasing HIV-1 prevalence from 2.3 to 4.6 % between 1996 and 2006 (10). Despite the declining HIV-2 prevalence, Guinea-Bissau is still the country in the world with the highest HIV-2 prevalence [10].

Loss to follow-up (LTFU) has emerged as a major problem in HIV programs throughout sub-Saharan Africa [11, 12]. Several sites in the region now experience high rates of LTFU among ART naïve patients [13–17], with a large proportion of patients disappearing between HIV testing and first CD4 cell count measurement [1]. A systematic review from Africa found that 40 % of patients were lost to follow-up with large variation in retention rates [18], and some studies have found an association with late initiation of ART, morbidity and mortality [11, 15, 19, 20]. Research on risk factors and specific reasons for LTFU have been done at several sites in sub-Saharan Africa, but there are variations between countries as well as clinics. One study from rural Uganda and one from urban/semi-rural Uganda have previously found that ‘Lack of transportation’, ‘Distance’ and ‘Transport costs’ to be the predominant reasons for LTFU among their patients. In another study, done in Kampala, Uganda, cost of transportation was only an issue in 1 % of the cases, whereas predominant reasons for LTFU were related to clinic factors such as a follow-up procedures and waiting times. In two studies from Johannesburg, transportation costs were mentioned as a reason by some patients, however, one of the major reasons for LTFU at both clinics were ‘relocating’ but subsequent reasons varied between them and included health related reasons, religious reasons, and fear of disclosure [17, 21–26]. High levels of LTFU can counteract the efforts to expand ART and thereby the efforts to limit the number of new HIV infections as well as mortality and morbidity related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [1].

In HIV treatment retention to care is paramount. For ART experienced patients interruption in treatment can lead to development of resistance which can be fatal in settings with limited access to second line treatment regimens, and for ART naive patients regular monitoring of CD4 cell count is important as to determine when to start treatment [20, 27]. In recent years, more and more research have focused on LTFU among HIV infected people, but as these patients are often difficult to trace back, only small groups are usually included. Risk factors for becoming lost to follow-up in the entire Bissau HIV Cohort have previously been described [28, 29], but no studies from Guinea-Bissau have described reasons as to why these patients become lost to care. The aim of this study was to ascertain vital status for a sample of patients lost to follow-up and to describe reasons for missing scheduled visits among patients still alive in the Bissau HIV Cohort.

Methods

Setting

This is a cross-sectional sample nested in a prospective cohort. It was carried out between May 15, 2013, and January 31, 2014, at the outpatient HIV clinic at Hospital Naçional Simão Mendes (HNSM) and at the Bandim Health Project, Bissau, Guinea-Bissau.

HNSM is the main hospital in Guinea-Bissau and houses the largest HIV clinic in the country. ART has been available in Guinea-Bissau since June 2005. Patients are referred to the clinic at HNSM from hospital wards and health centers in and around Bissau. Since 2007, patients attending the clinic have been enrolled in an ongoing HIV cohort. The cohort has been described in more details previously [28, 29]. On inclusion in the Bissau HIV Cohort a demographic questionnaire is filled in, and a follow-up questionnaire is performed whenever patients come for CD4 cell count measurements.

Bandim Health Project is a Demographic Surveillance Site (DSS), which consists of six areas (Bandim 1, Bandim 2, Belem, Mindara, Cuntum 1 and Cuntum 2). It has a total population of approximately 100,000 and censuses are performed on regular intervals [30].

Study design and population

The study population consisted of all HIV infected adults diagnosed at the HIV clinic before May 15, 2013. ART experienced patients usually come for follow-up visits every month, but because this population is very mobile, there can occasionally be up to 3 months between scheduled appointments. For this group, we defined LTFU as being absent from the clinic for at least 3 months since missing a scheduled appointment. Patients not on ART have follow-up visits every 6 months and unlike ART experienced patients, this interval is relatively consistent. They became categorized as lost to follow-up if they had been absent from the clinic for at least 6 months since missing a scheduled appointment [28, 29, 31].

Due to time and cost limitations, tracing was only feasible on a subset of patients. To use our resources most effectively, only patients living within the DSS were eligible for tracing. Statistical analyses were subsequently used to assess whether this sample was representative to the entire Bissau HIV cohort. After identifying patients who were lost to follow-up, additional contact information was extracted from patient charts and the DSS database.

Data collection

Tracing was carried out by phone and home visits. All patients and contact persons were called a minimum of three times if phone numbers had been provided. Contact by phone was done in an attempt to retrieve or verify address information, but also to give patients the opportunity to decline a visit from the field assistant. When tracing was successful, vital status was ascertained and if possible the patients were interviewed to determine reasons for disengagement from care. Semi-structured interviews were done face to face or by telephone by a trained field assistant. Patients were asked why they had not shown up for the scheduled appointment.

Statistical analyses

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables were compared using χ 2 tests for categorical variables. Two-sample t test (normal distribution) and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (non-normal distribution) were used for continuous variables. To calculate risk factors for LTFU Cox proportional hazard model was used and patients were included by date of HIV testing. In univariate analyses we included only patients under follow-up and patients lost to follow-up (excluding dead and transferred patients). Variables associated with LTFU with a P value <0.10, were included in multivariate analysis. In cases where data was missing, missing data groups were created thereby avoiding exclusion of patients. Patients were followed until date of last visit to the clinic if lost to follow-up or until May 15, 2013. Stata IC 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used to carry out all statistical analyses.

Results

Cohort characteristics

By May 15, 2013 a total of 5,472 patients had been diagnosed with HIV at the clinic. Of these 3,673 patients were included in the Bissau HIV cohort, 1,213/3,673 (33.0 %) men and 2,460/3,673 (67.0 %) women, (Table 1). HIV-1 was the most prevalent infection with 2,535/3,673 (69.0 %) being HIV-1 positive, 655/3,673 (17.8 %) HIV-2 positive, 419/3,673 (11.4 %) HIV-1/2 dually infected, and 64/3,673 (1.7 %) with no information about HIV type. The median age for all patients attending the clinic was 36 years (IQR 29–45 years) and the median CD4 cell count at baseline was 213 cells/µl (IQR 103–375 cells/µl). By May 15, 2013, a total of 169/3,673 (4.6 %) had been transferred to another medical facility, 382/3,673 (10.4 %) were registered as dead, and 1,849/3,673 (50.3 %) were lost to follow-up. The remaining 1,273/3,673 (34.7 %) came for regular check-up visits at the clinic.

Comparison between patients living inside and outside the DSS

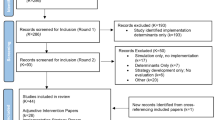

The majority of patients, 3,112/3,673 (84.7 %), had provided an address outside the DSS, while 561/3,673 (15.3 %) lived within the DSS, according to their last registered address (Fig. 1). Only patients in the latter group were eligible for tracing, therefore, comparisons were made on a range of variables to assess the validity.

The median age among patients living in the DSS (36 years, IQR 29–45 years) was similar to the median age among patients living outside the DSS (36 years, IQR 29–45 years, p = 0.70) (Table 2). There was no statistical significant difference in median CD4 cell count for patients living within and outside the DSS (210 vs. 213 cells/μl, IQR 94–371 vs. 104–377, p = 0.61) and no difference in the distribution of HIV types (387/557 (69.5 %) vs. 2,148/3,052 (70.4 %) HIV-1, 100/557 (18.0 %) vs. 555/3,052 (18.2 %) HIV-2 and 70/557 (12.6 %) vs. 349/3,052 (11.4 %) HIV-1/2 dually infected, p = 0.75), nor in whether patients were on ART or not at last clinic visit, with 2,084/3,112 (67.0 %) of the patients outside the DSS being on treatment and 389/561 (69.7 %) of the patients within the DSS being on treatment (p = 0.27). Of the patients living outside the DSS, 1,150/3,003 (38.3 %) answered that they had no schooling at all, while this proportion was only 147/541 (27.2 %) for patients living within the DSS (p < 0.01). Outside the DSS the main religion was Islam with 1,343/2,968 (45.3 %) followed by Catholicism with 701/2,968 (23.6 %). Within the DSS Catholicism was the most prevalent religion with 191/517 (36.9 %), whereas only 166/517 (32.1 %) were Muslims (p < 0.01). A bit less than half of the patients living outside the DSS were either Fula [723/3,076 (23.5 %)] or Balanta [731/3,076 (23.8 %)], whereas Pepel [100/556 (18.0 %)], Fula [88/556 (15.8 %)] and Manjaco [82/556 (14.8 %)] were the largest ethnic groups within the DSS (p < 0.01).

No differences were found in the distribution of transferred patients (149/3,112 (4.8 %) vs. 20/561 (3.6 %), p = 0.20), patients lost to follow-up (1,556/3,112 (50.0 %) vs. 293/561 (52.2 %), p = 0.33), patients under follow-up (1,094/3,112 (35.2 %) vs. 179/561 (31.9 %), p = 0.14) or deaths (313/3,112 (10.1 %) vs. 69/561 (12.3 %), p = 0.11).

Risk factors for LTFU in the study area

In Table 2 we compared patients on follow-up with the total number of patients lost to follow-up in the study area (patients who were registered dead or transferred to another HIV clinic were not included). Patients contributed with a total of 791 person-years of observation. In the multivariate analysis (Table 3), HIV-1/2 dually infected patients had an increased risk of being lost to follow-up (HR 1.51, 95 % CI 1.08; 2.11, p = 0.017), and so did patients who were not on ART compared with those on treatment (HR 4.14, 95 % CI 3.22; 5.33, p < 0.001). Comparing patients with a BMI >18.5 kg/m2 and a BMI ≤18.5 kg/m2 at inclusion, multivariate analysis showed that the latter was associated with being lost to follow-up with a HR of 1.38 (95 % CI 1.07; 1.17, p = 0.013).

Outcomes of tracing

Within the DSS, 293 patients were lost to follow-up by May 15, 2013. Of these patients, 13/293 (4.4 %) only showed up at the clinic for HIV testing, 49/293 (16.7 %) had a CD4 cell count measured but did not show up for the following consultation, 72/293 (24.6 %) were enrolled in follow-up but became lost before initiating treatment and 159/293 (54.3 %) became lost after commencing ART.

Ascertainment of vital status was successful in 193/292 (66.1 %) patients lost to follow-up and unsuccessful in 99/292 (33.9 %), often due to inadequate contact information. When field assistants located them, 125/292 (42.8 %) were still alive, while 68/292 (23.3 %) had died.

Comparison between patients where vital status was ascertained and patients where vital status was not ascertained

Median age at inclusion was 35 years for the group where vital status was ascertained and 36 years for the group where vital status was not ascertained (p = 0.262), while median CD4 cell count was 239 cells/µl vs. 211 cells/µl (p = 0.491). There was no difference in ART initiation (114/193 (59.1 %) vs. 54/99 (54.6 %), p = 0.459), HIV-type (HIV-1: 123/190 (64.7) % vs. 64/99 (64.7 %), HIV-2: 38/190 (20.0 %) vs. 19/99 (19.2 %), HIV-1/2 dual infection: 29/190 (15.3 %) vs. 16/99 (16.2 %), p = 0.973) or any other of the sociodemographic, arthropometric or hematological parameters in the two groups. When looking at median time from date of last visit to the clinic until tracing, the two groups showed a significant difference with a median time of 975 days (IQR 545–1342 days) in the group that was successfully tracked and 1,126 days (IQR 912–1392 days) in the other (p < 0.001).

Reasons for LTFU among tracked patients

Of the 125 patients that were found to be alive, the field assistant obtained reasons for LTFU (Table 4) for 103 patients. Reasons for not participating in this part of the study, were living outside Bissau, not having returned from travel, having gone travelling again or because we were not able to contact or locate the patient a second time.

Main reasons for LTFU were moving [30/103 (29.1 %)], travelling [18/103 (17.5 %)] and transferring [12/103 (11.7 %)] (Table 4). For 11/23 (47.8 %) there were no registered reasons for why they had been travelling. Among the rest “Illness or family obligation” [6/23 (26.1 %)], “Work or school” [4/23 (17.4 %)] and “Vacation” [2/23 (8.7 %)] were given as causes for travel (Table 5).

Discussion

This study has used a unique Demographic Surveillance Site setting to obtain further information on HIV patients lost to follow-up, and was able to locate four out of every ten LTFU. Vital status (death) was documented for additional patients but every third LTFU could not be traced. Risk factors for being LTFU were, being HIV-1/2 dually infected, not being on ART and having a BMI ≤18.5 kg/m2. Important reasons given for being LTFU were moving, travelling and transferring to another health care facility. Patients cited “Illness or family obligation”, “Work or school” and “Vacation” as reasons for travelling.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

In Guinea-Bissau, tracing a person is not only made difficult by people frequently moving and not having or knowing their addresses. Other factors contribute to making identification difficult, including confusion over given names and pet names, so-called house-names, which can be further complicated by several generations in a household sharing the exact same name. We chose that only patients living within the DSS were eligible for tracing to ensure the most effective use of resources, but this may have created a risk of selection bias if patients from the DSS are not representative for the entire cohort. While being representative on several parameters (sex, age, HIV type, ART initiation and CD4 cell count), they differed significantly on others (nutritional status, religion, ethnicity and schooling). A previous study has shown that a BMI ≤18.5 kg/m2, certain religions and no schooling were risk factors for LTFU at different levels in the program in this cohort, and it is possible that the differences between groups have led to a difference in reasons for LTFU [29].

This study looked at both, HIV-1, HIV-2 and HIV-1/2 dually infected adults, which sets it study apart from others because HIV-2 patients may have different reasons for being lost to follow-up as well as have different vital status compared with a cohort that only includes HIV-1 infected. We know that many HIV-2 infected patients have a lifespan similar to sero-negative individuals [32] and, therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other cohorts.

The study has a number of limitations. Both the group of patients that were available for tracing and the group providing detailed descriptions of reasons for LTFU were small, taking the sizable cohort into consideration, limiting the possibilities of stratifying results, on for example HIV type, and randomizing patients for tracing. Yet, considering similar studies on LTFU in sub-Saharan Africa, our study is comparable in size and flow of patients. The time that passed, from last visit at the clinic until tracing began, varied greatly between patients and this may affect the accuracy of the outcome. Furthermore, it is possible that certain reasons for LTFU will become overly represented due to recall bias and social desirability bias, thereby masking the true reasons for not returning. Finally, we only registered one cause for missing visits, and some patients may have had more than one reason for being absent.

Consistency with other studies

In recent years several large studies have been made on risk factors for LTFU in sub-Saharan Africa. They differ in size, definition of LTFU and whether they include both ART naïve and ART experienced patients, and to an extent they also differ in which associated risk factors they find, but male gender and malnourishment are often cited as risk factors. A recent study from four ART programs in sub-Saharan Africa (2 in Kenya, 1 in Malawi and 1 in Uganda) assessed 55.789 ART naive patients and found male gender, low BMI, advanced clinical stage and lower CD4 cell count to be associated with LTFU [21].

A Rwandan study using the same definition as we concluded that being male was associated with LTFU in both ART naive and ART experienced patients, and low CD4 cell count and advanced clinical stage were protective against LTFU in ART naïve patients [22]. Whilst these risk factors differ from ours, low BMI may be interpreted as an indicator for clinical progression of disease.

Reported reasons for LTFU seem to be recurring across cohorts, but the frequency with which they appear within a specific group varies. A study from Mbarara, Uganda, found lack of transport and distance to the clinic to be the primary reasons for becoming lost to follow-up, followed by lack of money, work responsibilities and child care responsibilities [23]. Our study on the other hand pointed towards the mobility of this population as a major issue for LTFU and studies from various settings have also found moving and transferring to another facility as prevailing reasons for LTFU among HIV patients [33–36]. However, illness and family obligations (for example caring for a sick family member or child care) emerges as a major factor when including patient reported reasons for going travelling (Table 5). This is also the case for reasons related to work obligations or transportation cost, if including the four patients that travelled because of work or school, and both findings are consistent with other reported studies [36, 37].

The differences in reasons and risk factors for LTFU may partly be explained by the difference in living conditions, social, cultural and political structures, that exists throughout sub-Saharan Africa, but also by the difference in HIV type between our cohorts and others.

There are possible explanations for the above-mentioned discrepancies in risk factors and reasons for LTFU. Cohorts are different in composition (sex workers, drug users, pregnant women, etc.) and this will most likely affect results, as will differences in geographical distribution, transport availability, employment numbers, social stigma and political discrimination.

Additionally, the various definitions of LTFU used can be a problem when comparing studies. Baring this in mind, it would be ideal to this field if a universal definition of LTFU is decided upon, but the different conditions of HIV programs across the world, does, however, make this a difficult task.

Meaning of the study: possible mechanisms and implications for clinicians or policymakers

Tracing and follow-up of patients have been used in many cohorts as a method of improving retention to care. This is, however, expensive and time consuming and will not be sufficient as cohorts grow with the international scale-up of ART [38]. Several studies report good effect of various interventions, such as the use of adherence support workers or mobile phones, but many are not currently within the range of public clinic budgets, even though studies have shown that it may be cost-effective to prevent LTFU and thereby improve survival [39–41]. This study takes a step towards understanding the underlying mechanisms of LTFU in Guinea-Bissau.

Unanswered questions and future research

A group of patients within the tracing sample remained lost to follow-up and vital status and reasons for LTFU remain unanswered within this group, which may affect results in either direction, under- or overestimating some risk factors or reasons. Further studies are needed to investigate if risk factors and reasons for becoming lost to follow-up vary between patients infected with different HIV types. A prospective study to assess the factors associated with LTFU in this cohort could be the next step on the way to reducing LTFU would be a possibility of getting further knowledge within this area.

Conclusion

LTFU in the Bissau HIV cohort was found to be high. Mortality was a frequent cause, but the high mobility of this population was the main reason, as well as reasons related to poor health literacy on the importance of maintaining follow-up.

References

WHO/UNICEF/UNAIDS. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Mills EJ, Bakanda C, Birungi J, Chan K, Ford N, Cooper CL, et al. Life expectancy of persons receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries: a cohort analysis from Uganda. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:209–16. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00358.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1105243.

Loutfy MR, Wu W, Letchumanan M, Bondy L, Antoniou T, Margolese S, et al. Systematic review of HIV transmission between heterosexual serodiscordant couples where the HIV-positive partner is fully suppressed on antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55747. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055747.

Nsanzimana S, Remera E, Kanters S, Chan K, Forrest JI, Ford N, et al. Life expectancy among HIV-positive patients in Rwanda: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e169–77. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70364-X.

Jean K, Gabillard D, Moh R, Danel C, Fassassi R, Desgrees-du-Lou A, et al. Effect of early antiretroviral therapy on sexual behaviors and HIV-1 transmission risk among adults with diverse heterosexual partnership statuses in Cote d’Ivoire. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:431–40. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit470.

WHO/UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

WHO/UNAIDS. UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report Results. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. p. 2012.

UNAIDS. GAP report: HIV estimates with uncertainty bounds 1990–2012. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourepidemic/epidemiologypublications/. Accessed 22 April 2014.

da Silva ZJ, Oliveira I, Andersen A, Dias F, Rodrigues A, Holmgren B, et al. Changes in prevalence and incidence of HIV-1, HIV-2 and dual infections in urban areas of Bissau, Guinea-Bissau: is HIV-2 disappearing? AIDS. 2008;22:1195–202. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328300a33d.

Bartlett JA, Shao JF. Successes, challenges, and limitations of current antiretroviral therapy in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:637–49. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(09)70227-0.

Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Myer L, Bangsberg DR, Boulle A, Nash D, et al. Early loss of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programmes in lower-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:559–67.

Larson BA, Brennan A, McNamara L, Long L, Rosen S, Sanne I, et al. Early loss to follow up after enrolment in pre-ART care at a large public clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:43–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02511.x.

Amuron B, Namara G, Birungi J, Nabiryo C, Levin J, Grosskurth H, et al. Mortality and loss-to-follow-up during the pre-treatment period in an antiretroviral therapy programme under normal health service conditions in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:290. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-290.

Togun T, Peterson I, Jaffar S, Oko F, Okomo U, Peterson K, et al. Pre-treatment mortality and loss-to-follow-up in HIV-1, HIV-2 and HIV-1/HIV-2 dually infected patients eligible for antiretroviral therapy in The Gambia, West Africa. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:24. doi:10.1186/1742-6405-8-24.

Castelnuovo B, Musaazi J, Musomba R, Ratanshi RP, Kiragga AN. Quantifying retention during pre-antiretroviral treatment in a large urban clinic in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:252. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0957-1.

Ahonkhai AA, Banigbe B, Adeola J, Onwuatuelo I, Bassett IV, Losina E, et al. High rates of unplanned interruptions from HIV care early after antiretroviral therapy initiation in Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:397. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1137-z.

Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e298. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298.

Colubi MM, Perez-Elias MJ, Elias L, Pumares M, Muriel A, Zamora AM, et al. Missing scheduled visits in the outpatient clinic as a marker of short-term admissions and death. HIV Clin Trials. 2012;13:289–95. doi:10.1310/hct1305-289.

Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, de Wolf F, Phillips AN, Harris R, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1352–63. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60612-7.

Bastard M, Nicolay N, Szumilin E, Balkan S, Poulet E, Pujades-Rodriguez M. Adults receiving HIV care before the start of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: patient outcomes and associated risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64:455–63. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a61e8d.

Mugisha V, Teasdale CA, Wang C, Lahuerta M, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Tayebwa E, et al. Determinants of mortality and loss to follow-up among adults enrolled in HIV care services in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85774. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085774.

Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, Emenyonu N, Bwana MB, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:405–11. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b843f0.

Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Geng EH, Kaaya SF, Agbaji OO, Muyindike WR, et al. Toward an understanding of disengagement from HIV treatment and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001369. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001369.

Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, Bender N, Egger M, Gsponer T, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1509–20. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03089.x.

Asiimwe SB, Kanyesigye M, Bwana B, Okello S, Muyindike W. Predictors of dropout from care among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy at a public sector HIV treatment clinic in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:43. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1392-7.

Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, Routman JS, Abroms S, Allison J, et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:41–9. doi:10.1089/apc.2008.0132.

Oliveira I, Andersen A, Furtado A, Medina C, da Silva D, da Silva ZJ, et al. Assessment of simple risk markers for early mortality among HIV-infected patients in Guinea-Bissau: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001587. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001587.

Honge BL, Jespersen S, Nordentoft PB, Medina C, da Silva D, da Silva ZJ, et al. Loss to follow-up occurs at all stages in the diagnostic and follow-up period among HIV-infected patients in Guinea-Bissau: a 7-year retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003499. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003499.

The official Bandim Health Project website. http://www.bandim.org/about-bhp.aspx. Accessed April 2014.

Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, Newman JE, Zhou J, Cesar C, et al. Universal definition of loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a statistical analysis of 111 facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001111. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001111.

Poulsen AG, Aaby P, Larsen O, Jensen H, Naucler A, Lisse IM, et al. 9-year HIV-2-associated mortality in an urban community in Bissau, west Africa. Lancet. 1997;349:911–4.

Wubshet M, Berhane Y, Worku A, Kebede Y. Death and seeking alternative therapy largely accounted for lost to follow-up of patients on ART in northwest Ethiopia: a community tracking survey. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59197. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059197.

Marson KG, Tapia K, Kohler P, McGrath CJ, John-Stewart GC, Richardson BA, et al. Male, mobile, and moneyed: loss to follow-up vs. transfer of care in an urban African antiretroviral treatment clinic. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78900. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078900.

Shastri S, Sathyanarayna S, Nagaraja SB, Kumar AM, Rewari B, Harries AD, et al. The journey to antiretroviral therapy in Karnataka, India: who was lost on the road? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18502. doi:10.7448/ias.16.1.18502.

Tweya H, Gugsa S, Hosseinipour M, Speight C, Ng’ambi W, Bokosi M, et al. Understanding factors, outcomes and reasons for loss to follow-up among women in Option B+ PMTCT programme in Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:1360–6. doi:10.1111/tmi.12369.

Lubega M, Musenze IA, Joshua G, Dhafa G, Badaza R, Bakwesegha CJ, et al. Sex inequality, high transport costs, and exposed clinic location: reasons for loss to follow-up of clients under prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in eastern Uganda–a qualitative study. Patient Preference Adherence. 2013;7:447–54. doi:10.2147/ppa.s19327.

Myer L, el-Sadr W. Expanding access to antiretroviral therapy through the public sector-the challenge of retaining patients in long-term primary care. S Afr Med J. 2004;94:273–4.

Torpey KE, Kabaso ME, Mutale LN, Kamanga MK, Mwango AJ, Simpungwe J, et al. Adherence support workers: a way to address human resource constraints in antiretroviral treatment programs in the public health setting in Zambia. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2204. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002204.

Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1838–45. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61997-6.

Losina E, Toure H, Uhler LM, Anglaret X, Paltiel AD, Balestre E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of preventing loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a Cote d’Ivoire appraisal. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000173. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000173.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and patients at the HIV clinic. Special thanks to João Paulo Nanque, Joana Mendes and Quintino Lopes Ié for their work with tracing patients and to Zacarias da Silva and the laboratory staff working in the TB and HIV sections at the National Public Health Laboratory and to the office staff at the Bandim Health Project for making this study possible.

The Bissau HIV Cohort study group comprises: Amabelia Rodrigues, David da Silva, Zacarias da Silva, Candida Medina, Ines Oliviera-Souto, Lars Østergaard, Alex Laursen, Bo Hønge, Peter Aaby, Anders Fomsgaard, Christian Erikstrup, Sanne Jespersen and Christian Wejse (chair).

Funding was provided by Institut for Klinisk Medicin, and National Institutes of Health (Grant No. U01AI069919) through IeDEA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

The HIV cohort at the outpatient clinic was approved by the National Ethics Committee in Guinea-Bissau in 2007 (Parecer NCP/No. 15/2007). Upon inclusion, patients sign a voluntary, informed consent, using fingerprint if illiterate. The cohort has an open approval to use data from patients’ records as long as patient confidentiality is not broken. This study was approved separately by the ethical committee in Guinea-Bissau (No. Ref. 060/CNES/INASA/2013). At all times field assistants were cautious not to disclose HIV status to anyone.

Conflict of interest

PBN has received funding from Institute of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Denmark. WAPHIR and IeDEA supported data collection in Bissau. For the remaining authors none were declared.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nordentoft, P.B., Engell-Sørensen, T., Jespersen, S. et al. Assessing factors for loss to follow-up of HIV infected patients in Guinea-Bissau. Infection 45, 187–197 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-016-0949-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-016-0949-0