Abstract

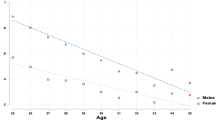

Norwegian registry data are used to investigate the location decisions of a full population cohort of young adults as they complete their education, establish separate households, and form their own families. We find that the labor market opportunities and family ties of both partners affect these location choices. Surprisingly, married men live significantly closer to their own parents than do married women, even if they have children, and this difference cannot be explained by differences in observed characteristics. The principal source of excess female distance from parents in this population is the relatively low mobility of men without a college degree, particularly in rural areas. Despite evidence that intergenerational resource flows, such as childcare and eldercare, are particularly important between women and their parents, the family connections of husbands appear to dominate the location decisions of less-educated married couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Rainer and Siedler (2012) use the same data to examine the effects of order and number of siblings on proximity to parents.

On the other hand, Bordone (2009) found that sociodemographic variables have similar effects on intergenerational proximity and contact in Italy and Sweden, and cannot fully explain the substantial North-South gap in these behaviors.

Her model yields a Harris-Todaro type “wait unemployment” result, wherein single women cluster in the big cities trying to capture Prince Charming.

Although patrilocality in anthropology is associated with strong rules and norms that a couple should live with or close to his parents, we use the term to refer to situations in which young couples choose where to live but where these choices tend toward greater proximity to his parents.

The model found in Rammohan and Robertsen (2012) has similar traits.

During the financial crisis of late 2009, Norwegian unemployment increased to only 3.1 %.

This breakdown of relocation motives is very similar to that in 2002–2003 Current Population Survey (CPS) data for the United States.

See Møen et al. (2004) for an overview of the variables in the administrative data sets. Also see Online Resource 1 for a full description of the data and variable construction.

Mothers are a natural choice of reference. First, the fathers may be missing from the register data, while mothers are always linked to the child at birth. Second, children mostly reside with mothers if parents divorce. Because only 7.69 % of parents were divorced by 1980, for most of our sample, parents are in the same distance category.

Konrad and Lommerud (1995) emphasized that in a model of a noncooperative family, public provision of childcare and eldercare can drive out corresponding services produced within the family, and this can increase women’s labor supply and improve women’s economic situation. Here we suggest another possible effect of public care provision: it may free the family to locate away from the grandparents on the female side, which might disadvantage women.

By 2005–2007, about one in four couples were cohabiting rather than married legally.

Statistics Norway estimated in 2002 that by age 50, about 37 % of men and 34 % of women remain unmarried. By age 34, 51 % of men and 39 % of women in our sample are not married. In our main analysis, we focus on married women by age 34 and their respective husbands (without age restriction). Thus, we include a large majority of married couples.

Malberg and Pettersson (2007) found that adult children in Sweden who are female, well-educated, and childless are more likely to live in a different region than their elderly parents.

Registry data link children to their mothers, so the number of children for married men at age 34 is constructed by linking married men to their spouses. Because we cannot link unmarried men to their wives, we do not know whether they have children.

Statistics Norway reports that 60 % of college attendees are female (Andreassen 2008).

The data on age of completion of education also contain post-qualifying education, which drives up the average age. The majority of these cohorts do not attend college and will end their education at age 16 (with 9 years of education) or 19 (with 12 years of education).

Distance category 0 is unobserved because location of school is measured at the municipality level.

This is because we can only follow the individuals to 2006, when our selected cohorts were 34–39. As shown herein, we include most of the first marriages by focusing on women married by age 34. We obtain very similar results if we construct the symmetric sample focusing on males married by age 34 and their wives.

We have also defined this sample as couples with parents in different counties, and we get similar results.

Kramarz and Skans (2007) found that family networks have an important influence on the transition from school to work in Sweden, and particularly for less-educated men, who tend to follow their fathers into jobs.

If the earnings returns to moving away are larger for rural-origin workers with low education as well as those with high education, then the probability of moving will also directly depend on parent’s location.

Family wealth would seem to have an ambiguous effect on location; greater parental resources increase the attractiveness of staying home near wealthy parents, but may also reduce the costs of distance by making travel and communication more economically feasible.

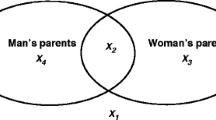

For simplicity, we assume that the couple takes for granted the location of both sets of siblings, so strategic interaction among siblings is neglected. The formulation of the welfare function is general enough to include the possibility that an individual considers the utility a sibling gets from higher utility for common parents, but this is not our central focus

When we use earlier measures of distance to parents, such as year after cohabitation, the gender effect is even larger. Also, when we run the ordered logit without any individual or family controls, we obtain an almost identical gender coefficient.

This is consistent with the findings of Rainer and Siedler (2009) and Compton and Pollak (2009). This result is not directly comparable with Konrad et al. (2002), who found that older siblings tend to move farther away from parents. The latter consider only the elder and younger sibling in two-children families, but we do not keep family size constant in this way.

Estimates at different life cycle points yield similar results. The gender differences are largest during the year after cohabitation.

We obtain very similar results when estimating the same models with distance measured at year after cohabitation and year after having first child as the dependent variables.

The results are evaluated at the mean of the independent variables for the two groups separately. However, they are roughly comparable: we tested the effects for the two groups while giving them the characteristics of the other group, and this does not significantly change the coefficients.

Unfortunately, we do not have data on occupations for everyone, especially parents. We tested whether this is a highly selected sample and found that the gender results and the characteristics of distances are very similar to the results for the total sample.

This classification is based on registry data for the total sample of 1967–1972 cohorts and group occupations according to whether the occupation has more than 75 % of either males or females. The occupation data do not distinguish between types of jobs within the different occupations.

One consequence of this tie may be limited marriage opportunities. We find that men in rural areas marry women with slightly lower levels of education than men in urban areas, conditional on their own education.

References

Andreassen, K. (2008). Cohabitation 2008. Oslo: Statistics Norway.

Baker, M. J., & Jacobsen, J. P. (2007). A human capital-based theory of postmarital residence rules. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 23, 208–241.

Bordone, V. (2009). Contact and proximity of older people to their adult children: A comparison between Italy and Sweden. Population, Space and Place, 15, 359–380.

Chiuri, M. C., & Del Boca, D. (2010). Home-leaving decisions of daughters and sons. Review of Economics of the Household, 8, 398–408.

Compton, J., & Pollak, R. A. (2007). Why are power couples increasingly concentrated in large metropolitan areas? Journal of Labor Economics, 25, 475–512.

Compton, J., & Pollak, R. A. (2009). Proximity and coresidence of adult children and their parents: Description and correlates (Michigan Retirement Research Center Working Paper wp215). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Costa, D. L., & Kahn, M. E. (2000). Power couples: Changes in the locational choice of the college educated, 1940–1990. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115, 1287–1315.

Cox, D. (2003). Private transfers within the family: Mothers, fathers, sons and daughters. In A. Munnell & A. Sunden (Eds.), Death and dollars: The role of gifts and bequests in America (pp. 168–209). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Edlund, L. (2005). Sex and the city. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107, 25–44.

Egerbladh, I., Kasakoff, A. B., & Adams, J. W. (2007). Gender differences in the dispersal of children in northern Sweden and the northern USA in 1850. The History of the Family, 12, 2–18.

Greenwell, L., & Bengtson, V. L. (1997). Geographic distance and contact between middle-aged children and their parents: The effects of social class over 20 years. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 52, S13–S16.

Hank, K. (2007). Proximity and contacts between older parents and their children: A European comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 157–173.

Hoel, E. (2009). Population statistics. Births. 2009. Oslo: Statistics Norway.

Iacovou, M. (2001). Leaving home in the European Union (ISER WP 2001–18). Essex, UK: Institute for Social and Economic Research.

Jacoby, H. G., & Mansuri, G. (2010). Watta satta: Bride exchange and women’s welfare in rural Pakistan. American Economic Review, 100, 1804.

Knoef, M., & Kooreman, P. (2011). The effects of cooperation: A structural model of siblings’ caregiving interactions (IZA Discussion Papers No. 5733). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Konrad, K. A., Kunemund, H., Lommerud, K. E., & Robledo, J. R. (2002). Geography of the family. American Economic Review, 92, 981–998.

Konrad, K. A., & Lommerud, K. E. (1995). Family policy with non-cooperative families. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 97, 581–601.

Kramarz, F., & Skans, O. N. (2007). With a little help from my . . . parents? Family networks and youth labor market entry (CREST Working Paper). Malakoff, France: Center for Research in Economics and Statistics.

Lawton, L., Silverstein, M., & Bengtson, V. (1994). Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 57–68.

Leonetti, D. L., Nath, D. C., & Hemam, N. S. (2007). The behavioral ecology of family planning in two ethnic groups in N.E. India. Human Nature, 18, 225–241.

Løken, K. V., Lommerud, K. E., & Lundberg, S. (2011). Your place or mine? On the residence choice of young couples in Norway (IZA Discussion Paper No. 5685). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Lundberg, S., & Pollak, R. A. (1996). Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 139–158.

Malmberg, G., & Pettersson, A. (2007). Distance to old parents. Demographic Research, 17(article 23), 679–704. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.23

McElroy, M. B. (1985). The joint determination of household membership and market work: The case of young men. Journal of Labor Economics, 3, 293–316.

Mincer, J. (1978). Family migration decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 86, 749–773.

Møen, J., Salvanes, K., & Sørensen, E. (2004). Documentation of the linked employer-employee data base at the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration. Unpublished manuscript, Norwegian School of Economics, Bergen, Norway.

Murdock, G. P. (1967). Ethnographic atlas. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Perelli-Harris, B., Kreyenfeld, M., Sigle-Rushton, W., Keizer, R., Lappegård, T., Jasiloniene, A., . . . DeGuilio, P. (2012). Changes in union status during the transition to parenthood in eleven European countries, 1970s to early 2000s. Population Studies, 66, 167–182.

Pettersson, A., & Malmberg, G. (2009). Adult children and elderly parents as mobility attractions in Sweden. Population, Space and Place, 15, 343–357.

Rainer, H., & Siedler, T. (2009). O brother, where art thou? The effects of having a sibling on geographic mobility and labour market outcomes. Economica, 76, 528–556.

Rainer, H., & Siedler, T. (2012). Family location and caregiving patterns from an international perspective. Population and Development Review, 38, 337–351. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00495.x

Rammohan, A., & Robertsen, P. E. (2012). Human capital, kinship, and gender inequality. Oxford Economic Papers, 64, 417–438.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Stark, O. (1989). Consumption smoothing, migration, and marriage: Evidence from rural India. Journal of Political Economy, 97, 905–926.

Sørlie, K. (2008). Bo- og Flyttemotivundersøkelsen 2008 [Living and Moving Survey 2008]. Oslo, Norway: Presented at Demografisk Forum.

Statistics Norway. (2005). Statistisk årbok, 2005. Oslo: Statistics Norway.

Sweetser, D. A. (1963). Asymmetry in intergenerational family relationships. Social Forces, 41, 346–352.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gordon Dahl, Kjell Salvanes, and participants at a workshop at the University of Michigan (2009), a seminar at the University of Bergen (2009), and a workshop on Taxation and the Family in Munich (2010) for valuable comments. Løken and Lommerud thank the Research Council of Norway for financial support. Lundberg is grateful for financial support from the Castor Professorship in Economics at the University of Washington.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Løken, K.V., Lommerud, K.E. & Lundberg, S. Your Place or Mine? On the Residence Choice of Young Couples in Norway. Demography 50, 285–310 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0142-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0142-8