Abstract

I examine the potential impact of the anticipated future marriage squeeze on nuptiality patterns in China and India during the twenty-first century. I use population projections from 2005 to 2100 based on three different scenarios for the sex ratio at birth (SRB). To counteract the limitations of cross-sectional methods commonly used to assess the severity of marriage squeezes, I use a two-sex cohort-based procedure to simulate marriage patterns over the twenty-first century based on the female dominance model. I also examine two more-flexible marriage functions to illustrate the potential impact of changes in marriage schedules as a response to the marriage squeeze. Longitudinal indicators of marriage squeeze indicate that the number of prospective grooms in both countries will exceed that of prospective brides by more 50% for three decades in the most favorable scenario. Rates of male bachelorhood will not peak before 2050, and the squeeze conditions will be felt several decades thereafter, even among cohorts unaffected by adverse SRB. If the SRB is allowed to return to normalcy by 2020, the proportion of men unmarried at age 50 is expected to rise to 15% in China by 2055 and to 10% in India by 2065. India suffers from the additional impact of a delayed fertility transition on its age structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Data used in this section are based on United Nations estimates for 1950–2005 complemented by projection results for the period beyond 2005.

According to my projections, the overall yearly decline in birth cohort size during the 2005–2100 period is 0.25% in China and 0.4% in India (rapid transition scenario).

No projection exists for India. Forecasts of China’s future sex imbalances (Attané 2006; Tuljapurkar et al. 1995) are based on 1990 or 2000 census data and on fixed fertility and mortality assumptions. Estimates provided by Jiang et al. (2007) follow a more realistic demographic scenario. An alternative method based on nuptiality tables has also been proposed by Jiang (2011).

Kulkarni (2010) analyzed the recent SRB downturn in India; see also Sharma and Haub (2008). Chinese trends are described in Das Gupta et al. (2009) and Guilmoto and Ren (2011). Preliminary data from the Chinese 2010 census put the sex ratio at birth at 118, confirming the slight downturn. Original data are found in the reports of the 2000 census and of the 2005 1% sample survey for China, while Indian data are from the annual reports of the Sample Registration System.

Little’s law states that the average number in a given stable system is equal to the rate of new arrivals in the system multiplied by their average time in the system (Tijms 2003:50–52).

Jones (2007) provides the most recent comprehensive synthesis of nuptiality in East Asia. Detailed statistics and case studies are also available in Jones and Ramdas (2004) and Xenos et al. (2006), as well as in United Nations (1990) for trends prior to the 1990s. See also Retherford et al. (2001) on Japan, and Kwon (2007) on South Korea.

This figure is slightly above that of Kerala women today but still distinctly below that of Sri Lankan women (Caldwell 2005).

I am grateful to the suggestion of an anonymous reviewer on this point.

Better marriage opportunities for women and lower dowry costs in high sex-ratio societies are among the hypotheses put forward by Guttentag and Secord (1983).

For simplicity, the effects of birth imbalances and age-structural change on the marriage squeeze are assumed to be additive.

For critical discussion of the HM model, see Iannelli et al. (2005:38–41). See also Hinaba’s observations (2000:395). A long-term study of nuptiality patterns in Spain using the HM model concluded that most changes were driven more by behavioral factors than by age-sex compositional changes (Esteve et al. 2009).

These estimates are derived from the difference between the proportion single as of 2005 and the simulated figure in the rapid-transition scenario (FD model).

For weighted sex ratios corrected for remarriages, see Jiang et al. (2007:357).

Age-specific marriage rates have to be adjusted in the FD model in order to achieve the desired age gap between men and women. The specific age distributions of unmarried men and fluctuations in cohort size (especially in China) tend to distort the observed age at first marriage among men.

References

Attané, I. (2006). The demographic impact of a female deficit in China, 2000–2050. Population and Development Review, 32, 755–770.

Attané, I., & Guilmoto, C. Z. (Eds.). (2007). Watering the neighbour’s garden: The growing demographic female deficit in Asia. Paris, France: CICRED.

Banister, J. (2004). Shortage of girls in China today. Journal of Population Research, 21, 19–45.

Blanchet, T. (2005). Bangladeshi girls sold as wives in north India. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 12, 305–334.

Cai, Y. (2008). An assessment of China’s fertility level using the variable-r method. Demography, 45, 271–281.

Caldwell, B. K. (2005). Factors affecting female age at marriage in South Asia: Contrasts between Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Asian Population Studies, 1, 283–301.

Chen, M. (2000). Perpetual mourning: Widowhood in rural India. Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Croll, E. (2000). Endangered daughters: Discrimination and development in Asia. London, UK: Routledge.

Das Gupta, M., Chung, W., & Li, S. (2009). Evidence for an incipient decline in numbers of missing girls in China and India. Population and Development Review, 35, 401–416.

Davin, D. (2005). Marriage migration in China: The enlargement of marriage markets in the era of market reforms. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 12, 173–188.

Esteve, A., & Cabré, A. (2005). Los efectos del decrecimiento de las cohortes sobre la constitución familiar: Evidencia histórica comparada en España, Francia y Estados Unidos, 1920–1940 [The effects of the decrease of birth cohorts on family building: Comparative historical evidence from Spain, France and the United States, 1920–1940] (Papers de Demografia No. 262). Barcelona, Spain: Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics.

Esteve, A., Cortina, C., & Cabré, A. (2009). Long term trends in marital age homogamy patterns: Spain, 1922–2006. Population, 64, 173–202.

Goodkind, D. (2006, March). Marriage squeeze in China: Historical legacies, surprising findings. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Los Angeles, CA.

Goodkind, D. M. (2008, April). Fertility, child underreporting, and sex ratios in China: A closer look at the current consensus. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, LA.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2009). The sex ratio transition in Asia. Population and Development Review, 35, 519–549.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2010). Longer-term disruptions to demographic structures in China and India resulting from skewed sex ratios at birth. Asian Population Studies, 1, 3–24.

Guilmoto, C. Z., & Ren, Q. (2011). Socio-economic differentials in birth masculinity in China. Development and Change, 5, 1269–1296.

Guttentag, M., & Secord, P. F. (1983). Too many women? The sex ratio question. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Hinaba, H. (2000). Persistent age distributions for an age-structured two-sex population model. Mathematical Population Studies, 7, 365–398.

Hudson, V. M., & den Boer, A. M. (2004). Bare branches: Security implications of Asia’s surplus male population. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Iannelli, M., Martcheva, M., & Milner, F. A. (2005). Gender-structured population modeling. Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). (2007). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences.

Jiang, Q. (2011, October). Marriage squeeze, never married and mean age at first marriage. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Gender and Sustainable Social Development: Consequences and Public Policies, Xi’an, China.

Jiang, Q., Attané, I., Li, S., & Feldman, M. W. (2007). Son preference and the marriage squeeze in China: An integrated analysis of the first marriage and the remarriage market. In I. Attané & C. Z. Guilmoto (Eds.), Watering the neighbour’s garden: The growing demographic female deficit in Asia (pp. 347–365). Paris, France: CICRED.

Jones, G. W. (2007). Delayed marriage and very low fertility in Pacific Asia. Population and Development Review, 33, 453–478.

Jones, G. W., & Ramdas, K. (Eds.). (2004). (Un)tying the knot: Ideal and reality in Asian marriage. Singapore: Asia Research Institute.

Joseph, J., & Center for Youth Development and Activities (CYDA). (2007). Reflections on the campaign against sex selection and exploring ways forward (Report). Pune, India: CYDA, for the United Nations Population Fund.

Kaur, R. (2004). Across-region marriages: Poverty, female migration and the sex ratio. Economic and Political Weekly, 39, 2595–2603.

Keilman, N. (1985). Nuptiality models and the two-sex problem in national population forecasts. European Journal of Population, 1, 207–235.

Keyfitz, N., & Caswell, H. (2005). Applied mathematical demography. New York: Springer.

Kim, D.-S. (Ed.). (2008). Cross-border marriage: Processes and dynamics. Seoul, Korea: Institute of Population and Aging Research, Hanyang University.

Kulkarni, P. M. (2010). Tracking India’s sex ratio at birth: Evidence of a turnaround. In K. S. James, A. Pandey, D. W. Bansod, & L. Subaiya (Eds.), Population, gender and health in India: Methods, processes and policies (pp. 191–210). New Delhi, India: Academic Foundation.

Kwon, T.-H. (2007). Trends and implications of delayed and non-marriage in Korea. Asian Population Studies, 3, 223–241.

Le Bach, D., Bélanger, D., & Hong, K. T. (2007). Transnational migration, marriage and trafficking at the China-Vietnam border. In I. Attané & C. Z. Guilmoto (Eds.), Watering the neighbour’s garden: The growing demographic female deficit in Asia (pp. 393–425). Paris, France: CICRED.

Li, S., Wei, Y., Jiang, Q., & Feldman, M. W. (2007). Imbalanced sex ratio at birth and female child survival in China: Issues and prospects. In I. Attané & C. Z. Guilmoto (Eds.), Watering the neighbour’s garden: The growing demographic female deficit in Asia (pp. 25–48). Paris, France: CICRED.

Lutz, W., Sanderson, W., Scherbov, S. (2008). IIASA’s 2007 probabilistic world population projections (IIASA World Population Program Online Data Base). Laxenburg, Austria: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. Retrieved from http://www.iiasa.ac.at/Research/POP/proj07/index.html?sb=5

Lutz, W., Scherbov, S., Cao, G.-Y., Ren, Q., & Zheng, X. (2007). China’s uncertain demographic present and future. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2007, 37–59.

Mari Bhat, P. N. (2002a, December 21). On the trail of “missing” Indian females, I: Search for clues. Economic and Political Weekly, 37, 5105–5118.

Mari Bhat, P. N. (2002b, December 21). On the trail of “missing” Indian females, II: Illusion and reality. Economic and Political Weekly, 37, 5244–5263.

Mari Bhat, P. N., & Halli, S. S. (1999). Demography of brideprice and dowry: Causes and consequences of the Indian marriage squeeze. Population Studies, 53, 129–149.

McDonald, P. (1995). L’équilibre numérique entre hommes et femmes et le marché matrimonial: Le point sur la question [The numerical balance between men and women and the marriage market: An update]. Population, 6, 1579–1590.

Miller, B. (2001). Female-selective abortion in Asia: Patterns, policies, and debates. American Anthropologist, 103, 1083–1095.

Okun, B. S. (2001). The effects of ethnicity and educational attainment on Jewish marriage patterns: Changes in Israel, 1957–1995. Population Studies, 55, 49–64.

Pandey, K. K. (2003). Female foeticide, coerced marriage & bonded labour in Haryana and Punjab. A situational report. Faridabad, Haryana: Shakti Vahini.

Patel, T. (Ed.). (2006). Sex selective abortion in India: Gender, society and new reproductive technologies. New Delhi, India: Sage Publications.

Qian, Z., & Preston, S. H. (1993). Changes in American marriage, 1972 to 1987: Availability and forces of attraction by age and education. American Sociological Review, 58, 482–495.

Rallu, J.-L. (2006). Female deficit and the marriage market in Korea. Demographic Research, 15(article 3), 51–60. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.3

Raymo, J. M., & Iwasawa, M. (2005). Marriage market mismatches in Japan: An alternative view of the relationship between women’s education and marriage. American Sociological Review, 70, 801–822.

Retherford, R. D., Choe, M. K., Chen, J., Xiru, L., & Hongyan, C. (2005). How far has fertility in China really declined? Population and Development Review, 31, 57–84.

Retherford, R. D., Ogawa, N., & Matsukura, R. (2001). Late marriage and less marriage in Japan. Population and Development Review, 27, 65–102.

Schoen, R. (1981). The harmonic mean as the basis of a realistic two-sex marriage model. Demography, 18, 201–216.

Sharma, O. P., & Haub, C. (2008, August). Sex ratio at birth begins to improve in India. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/Articles/2008/indiasexratio.aspx

Tijms, H. C. (2003). A first course in stochastic models. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Tuljapurkar, S., Li, N., & Feldman, M. W. (1995). High sex ratios in China’s future. Science, 267, 874–876.

United Nations. (1990). Patterns of first marriage: Timing and prevalence. New York: Department of International Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

United Nations. (2004). World population to 2300. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

United Nations. (2007). World population prospects: The 2006 revision population database. New York: United Nations, Population Division.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2007, October). Sex-ratio imbalance in Asia: Trends, consequences and policy responses. Studies of China, India, Nepal and Viet Nam presented at the 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Hyderabad, India. Retrieved from http://www.unfpa.org/gender/case_studies.htm

Wei, S. J., & Zhang, X. (2009). The competitive saving motive: Evidence from rising sex ratios and savings rates in China (NBER Working Paper No. w15093). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Xenos, P., Achmad, S., Lin, H.-S., Luis, P. K., Podhisita, C., Raymundo, C., & Thapa, S. (2006). Delayed Asian transitions to adulthood: A perspective from national youth surveys. Asian Population Studies, 2, 149–185.

Zeng, Y. (2007). Options for fertility policy transition in China. Population and Development Review, 33, 215–246.

Zeng, Y., Tu, P., Gu, B., Xu, Y., Li, B., & Li, Y. (1993). Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratio at birth in China. Population and Development Review, 19, 283–302.

Acknowledgments

I thank my colleagues at UNFPA, CEPED, and CEDEPLAR for their suggestions on my preliminary presentations. Additional help from Isabelle Attané, Eva Lelièvre, Zoé E. Headley, Gavin Jones, and Ines G Županov on a previous version is gratefully acknowledged. Anonymous reviewers for Demography also provided detailed and useful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Parameters for Population Projection

Table 3 summarizes the parameters used for the projections of China’s and India’s populations until 2100 (see also Guilmoto 2010). Projections were done with the cohort-component method of the software package Spectrum (DemProj model), under the assumption of no international migration during the period under examination. Population figures and demographic parameters were borrowed from the medium variant of the world projections by the United Nations (2007). For the 2005 baseline year, population and demographic parameters come from the United Nations estimates, and these parameters incorporate in particular the current level of female excess mortality among children. However, two adjustments were necessary for China. First, the sex distribution derived from the 2005 1% survey—in which male adults are severely underestimated—was corrected by using the estimated sex ratio for the entire population in 2005 and the cohort-specific sex ratio for adults aged 15–54 during the 2000 census. Second, China’s fertility in 2005 was taken as 1.6 children per woman, a medium value derived from available TFR estimates by Cai (2008), Lutz et al. (2007), Retherford et al. (2005), and Zeng (2007). Values used for the 2050–2100 period were derived from two different sets of long-term projections prepared by IIASA (Lutz et al. 2008) and by the United Nations (2004).

The first two SRB scenarios described in the text are used to calculate the share of male and female births in each five-year birth cohort in 2005–2100. SRB figures used for 2005 (120 for China and 113 for India) are taken from the 2005 1% survey for China and from estimates by the Sample Registration System for India. The most recent estimate by China’s National Bureau of Statistics puts the SRB at 121 for 2008. It remains that SRB levels used here are only estimates in view of the possibility of underenumeration of girls in China and of sample issues in India.Footnote 17 I have not attempted here to provide an alternative set of SRB estimates, and only the next round of censuses in both countries will provide the more detailed figures required to reestimate SRB levels. But in order to account for the possibility of female underregistration in China, I have also run a set of simulations with lower SRB (see Appendix C).

For the simulation based on normal SRB (with SRB constant at 105), I also corrected the 2005 baseline data for China and India because they are affected by past SRB imbalances. To do this, I modified the 2005 sex distribution of the population below 25 years in order to reflect a normal sex ratio distribution. For India, I computed correction factors for each five-year period since 1980 based on SRB estimates (see Kulkarni 2010), and I applied them to the 2005 sex ratio for all age groups below 25 years to compute the corrected sex and age distributions used in this projection. In the absence of a similar series for China, I used the average sex ratios of five-year age groups computed from United Nations estimates for the world after removing China and India.

Appendix B: Parameters and Procedure for Marriage Simulations

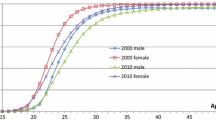

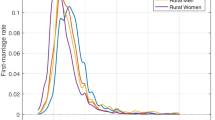

The nuptiality parameters are given in Table 4, starting with estimates for 2005. Because neither China nor India publishes marriage rates by age, I had to resort to indirect estimates based on successive age and sex distributions by marital status to compute the nuptiality table for 2000–2005 by five-year age group from age 15 to 50. The marriage schedules for China were computed longitudinally by combining the distributions from the 2000 census and the 2005 1% survey. Similarly, I used the two NFHS rounds of 1998–1999 and 2005–2006 (IIPS 2007) for India. The 2005 marriage rates from ages 15 to 50 have been used to compute the weighted adult sex ratio (computed on age distributions weighted by age-specific marriage rates) displayed in Figs. 1 and 2.Footnote 18

To simulate marriages in five-year cohorts, I used the marriage probabilities derived from marriage schedules as well as a correction factor in order to account for remarriage (below age 50). This correction coefficient for remarriage was derived from two sources: the proportion remarried in the 2000 and 2005 Chinese surveys, and the proportion of remarried men and women in India according to the latest NFHS data for India. From the standard marriage schedules, I also derived other marriage schedules used in the models for the second half of the twenty-first century by increasing the proportion marrying after age 25 (women) and 30 (men). The marriage simulations are limited to unions occurring before the age of 50.

The simulation process starts from the 2005 five-year age distributions by sex and marital status. The number of expected first marriages for men and women in 2005–2010 is calculated from the marriage probabilities and the single population in 2005.Footnote 19 The MSI (Figs. 1 and 2) is computed as the sex ratio of these expected first marriages after correction for remarriages. Because of the male preponderance, this ratio is usually above 100, and the final number of simulated first marriages is determined by using one of the marriage models described below. The number of men and women remaining single in 2010 is then computed for each cohort from the projected populations and the simulated numbers of first marriages during 2005–2010 according to each marriage function. With the computed 2010 distributions by age and marital status, the same procedure is then repeated successively until 2100, with specific nuptiality parameters for each five-year interval (Table 4).

This article uses the following marriage models:

-

1.

In the female dominance (FD) model (Table 1), the number of simulated marriages is set by the number of expected female marriages. In the case of male surplus, male marriages are uniformly reduced across all age groups to match the available supply of brides. In this model, female nuptiality patterns are also allowed to change gradually over the period 2005–2050 (rise in age at first marriage in China and India, change of remarriage coefficients in India), but the difference in age at marriage between men and women remains constant throughout.

-

2.

The delayed male marriage (DMM) model (Table 2) is a variant of the previous FD model, in which the male age at marriage is made to rise faster than the female age at marriage; the spousal age difference increases by two years in China and India from 2005 to 2050 and remains constant afterward.

-

3.

In the harmonic mean (HM) model (Table 2), the simulated number of marriages is the harmonic mean of male and female expected marriages (Keilman 1985). With M representing the expected number of male marriages and F representing female marriages, the actual number of marriages, μ, is computed as

. The adjustment ratio (simulated number / expected number) is applied to expected marriage rates by age and sex. The adjusted probability of marriage is capped to one in each age group.

. The adjustment ratio (simulated number / expected number) is applied to expected marriage rates by age and sex. The adjusted probability of marriage is capped to one in each age group.

Appendix C: Sensitivity Analysis of Female Birth Underreporting

As indicated previously, SRB levels used here are only estimates since data for China and India are not based on exhaustive civil registration sources; my simulation exercise remains therefore potentially sensitive to the quality of the estimates. To assess the sensitivity of the model, I ran a different set of population projections and marriage simulations based on lower SRB levels. I restricted the analysis to China, where SRB is both higher and more likely to be affected by estimation issues than India. In particular, Chinese fertility is notoriously underestimated by recent surveys and censuses, and female births might be more underreported than male births, resulting in exaggerated SRB estimates.

Based on this hypothesis, I postulate here that the real SRB is 113 in 2005, with male and female underreporting rates of 15% and 20%, respectively. This corresponds to an excess of 5% in underreporting rates for female births. Applying this rather high level of selective female underregistration will help to assess the sensitivity of the simulations. All other population and marriage parameters are kept similar to those of the rapid-transition scenario shown in Table 4.

Results in Table 5 demonstrate that a lower SRB contributes to reducing the male excess in the marriage market and to increasing the male probability to marry. However, the overall impact of lower SRB (113 in 2005) seems barely visible before the 2040s and remains modest thereafter. For instance, the MSI diminishes from 157 in 2040 to 151 according to the lower SRB scenario. The difference between the two series almost disappears after 2060. The estimated proportion of unmarried men at 50 also rises more slowly during 2050–2080 with these parameters, but the difference with the standard SRB scenario never exceeds 1%. This sensitivity analysis suggests therefore that SRB overestimation may exert but a minor effect on the simulation results.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guilmoto, C.Z. Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth and Future Marriage Squeeze in China and India, 2005–2100. Demography 49, 77–100 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0083-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0083-7

. The adjustment ratio (simulated number / expected number) is applied to expected marriage rates by age and sex. The adjusted probability of marriage is capped to one in each age group.

. The adjustment ratio (simulated number / expected number) is applied to expected marriage rates by age and sex. The adjusted probability of marriage is capped to one in each age group.