Abstract

This paper analyzes the effect of competition in a dynamic contest in which agents of two types (A and B) differ in their expected performances; environments where type A outperforms type B are more frequent than those where B outperforms A. In each period, the population of agents is randomly matched in groups of n members (each group faces a particular environment), with the top \(k<n\) performing agents from each group being the winners of the prizes. Hence, the ratio \(\frac{k}{n}\) determines the proportion of winning agents in each group. This ratio also describes the strength of competition in the group: the lower \(\frac{k}{n}\) is, the higher the level of competition is. Our results show that type A eventually dominates the entire population with moderate competition, but type B survives in the long run for high levels of competition. Hence, we obtain that no matter how low the expected success rate of a type is, if the strength of competition is high enough those agents with the lowest expected success rate survive in the long run.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The most common use of contests is as mechanisms to create incentives to work harder. However, they can also be used as selection mechanisms. For example, a contest can select agents that differ in their expected efficiency levels. This can be relevant if the institution or principal cannot either impose the strategy to be followed by an agent or observe the type of agent. We seek to study the role of the number of prizes (k) and the number of contestants (n) in the outcome of the selection process.Footnote 1 These institutional parameters define a ratio \(\frac{k}{n}\), which can be seen as a measure of the strength of competition. For example, if \(k=1\) and \(n=3\), three agents compete for only one prize in every group. Similarly, if \(k=1\) and \(n=10\) then 10 agents compete for only one prize. Note that in the second case competition is higher (ceteris paribus). Hence, the strength of competition increases as ratio \(\frac{k}{n}\) decreases. We focus on a specific kind of selection, in particular this “strength of competition” in a contest, so we take an evolutionary approach. To that end, we consider a large population with two possible types of behavioral agents: A-agents and B-agents, where environments where type A outperforms B are more likely to occur than environments where B outperforms A. In this sense, A is a better type because it has a higher expected success rate.Footnote 2

In this population of agents, we consider that each individual interacts with randomly selected individuals.Footnote 3 Thus, groups are formed by a random matching process. However, a random matching process would generate a very complicated stochastic system. In the economic literature, for large populations (either countable or uncountable) the population dynamic is usually approximated by a deterministic process, where the frequency of different matches is identified with their corresponding expectations. This simplifying assumption is analyzed in several papers from different points of view. Examples include Boylan (1992, 1995), Alós-Ferrer (1999), and Duffie and Sun (2012). In Sect. 2, we make some assumptions that guarantee the existence of a matching process, so we can consider the deterministic process presented in this paper as a good approximation of the complex stochastic system.

In the literature on evolutionary selection models the matching process is usually made in pairs, which is a particular case of group size, \(n=2\), where one agent is selected, \(k=1\). We must consider a more general matching process in which \(n\ge 2\), and \(k\ge 1\) agents are selected. However, the rationale in this setting is the same as in matching in pairs. We consider that there is a continuum population of agents, and we work with the proportions of different kinds of groups of agents.

To sum up, this paper analyzes the effect of strength of competition on the characteristics of the successful agents. To that end, we consider that at \( t=0\) each agent is given one behavioral rule, either A or B. They are not strategic, so they become agents of type A or B. At each t, the population of A and B agents is randomly matched in groups of n agents, with members of each group competing with each other, and each group facing a particular environment. The mechanism selectsFootnote 4 the top \(k<n\) performing agents from each group, with \(k\in \{1,2,3,\ldots \}\) and \( n\in \{2,3,\ldots \}\). We assume that at \(t+1\) nonwinners imitate the action of winners at t, so the population at \(t+1\) reproduces the distribution of the type of winners at t.Footnote 5 Consequently, the proportion of A-agents in the population is equal to that of the winners. Then they are again randomly matched and the process repeats. We seek to learn how this competition process changes the characteristics of the population.

There is an alternative imitative behavior, which adds a different but very interesting point of view of the dynamic process. Nevertheless, the resulting dynamic is the same as in the first imitative assumption. Let x be the number of A-agents in a group (and \(\left( n-x\right) \) the number of B-agents). Under this second imitation behavior, regardless of what environment a group is facing, if the number of individuals who successfully match the environment exceeds a threshold k then the entire group adopts the strategy matching the environment. However, if the number of agents is below the threshold k then in groups facing environment A only a fraction \(\frac{x}{k}\) of the members adopt the strategy matching the environment, strategy A, and the remaining \(1-\frac{x}{k}\) adopt B.Footnote 6 Similarly, in groups facing environment B only a fraction \( \frac{n-x}{k}\) copy B and the rest copy A. This basically means that even if one strategy proves more successful with the current environment it will not automatically dominate the group unless it is sufficiently represented. The higher k is, the more easily the members of the group imitate successful behavior. Thus, the ratio \(\frac{k}{n}\) measures the minimum proportion of members of the group matching the environment needed to cause all members to copy the successful action. Therefore, this ratio also measures the level of conformity in this population. The higher \(\frac{k }{n}\) is, the more successful agents are needed to cause the group to change behavior, so changing behavior becomes more difficult. On the other hand, a lower \(\frac{k}{n}\) makes success more important relative to conformism and the environment becomes more competitive. Therefore, in this context, conformism and competition are correlated. In addition, notice that, after both imitation rules, the proportion of A-agents among the nonwinners is equal to the proportion of A-agents in the population of winners. Thus, we can focus on the proportion of A-agents among the agents selected and study how the strength of competition changes the distribution of the population.

In this model A-agents perform better than B-agents more often, so we should expect an increase in the strength of competition to punish B-agents and the proportion of B-agents to decrease as competition increases. However, our results show that an increase in competition does not always work this way: In particular, we find that for high enough levels of competition B-agents can persist in the long run, despite being expected to perform worse.

More precisely, depending on the strength of competition we find three possible cases: Cases L, M and H. First, case L: If the strength of competition is too low, the selection process is not strong enough to offset the inertia of the initial population. The dynamic thus depends on the initial conditions and the population eventually becomes homogeneous, i.e. with only type A or type B persists in the long run. Second, case M: If the strength of competition increases (intermediate level) the whole population will become A-agents for any initial mixed population. In this case the selection process is strong enough to eventually select the best performers, as expected. Finally, case H: if competition increases far enough, B-agents also survive.Footnote 7 Thus, surprisingly, we show that no matter how low the success rate of a type is, if the strength of competition is high enough agents of that type survive in the long run. In other words, too much competition is always harmful to the best performers. The intuition behind our results is broadly explained in Sect. 3.1.

The contribution of this paper is twofold. First, it presents a family of contest selection mechanisms that parameterizes the strength of competition in a simple way. In evolutionary models agents are usually matched in pairs and one of them is selected. This paper generalizes this idea in contests and considers matchings of n agents with \(k<n\) agents selected. Second, we show that this generalization is not innocuous but has a surprising result even in a very simple model. As far as we are aware, there are no similar approaches in the literature on evolutionary models.

Our approach is concerned with designing a suitable selection mechanism, which depends on the objective function of the institution.Footnote 8 This approach is related to some extent to classic mechanism design, especially principal-agent models. In such models the information that players have about others players and their individual choices has a major role in the design of the mechanism. However, our approach puts the focus on an institutional characteristic, i.e. the strength of competition, and we try to highlight that it can be an important factor to be considered even in a simple model.

This paper is related to Harrington (1998, 1999a, b, 2000, 2003) and Garcia-Martinez (2010) because our mechanism can be seen as a generalization of theirs. Harrington uses a selection process in a hierarchical structure to compare the performance of rigid behavior with that of flexible behavior. Agents are randomly matched in pairs (\(n=2\)) and one of them is selected. Thus, the strength of competition is fixed. Garcia-Martinez (2010) analyzes a promotion system that works in two steps. The first step is like Harrington’s mechanism: Agents are matched in pairs and one of them is selected. In the second step, the agents selected in the first step are pooled together and the top fraction \(\theta \) of best-performing agents is eventually selected; this is referred to as “global selection”. In Vega-Redondo (2000) a hierarchical structure is used to select agents, who play in pairs (\(n=2\)) a \(2 \times 2\) coordination game, where there is only global selection. The present paper is also related to the literature on tournaments produced since the seminal paper by Lazear and Rosen (1981), in particular to those papers that focus on the selection role of contests, e.g., Rosen (1986), Section V, Hvide and Kristiansen (2002), Tsoulouhas et al. (2007), Azmat and Möller (2009), and Groh et al. (2012).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes the model and the dynamic equation; Sect. 3 analyzes the dynamics, discusses the results, and provides some intuitions; Sect. 4 analyzes the convergence time; and Sect. 5 concludes.

2 The model

At time t there is a continuous population of A and B agents. Let \( a_{t}\in \left[ 0,1\right] \) denote the proportion of A-agents at time t , and \(1-a_{t}\) the proportion of B-agents. The dynamic function \( a_{t+1}=f(a_{t})\) describes the evolution of the proportion of A-agents at time \(t+1\) as a function of the proportion of A-agents at t. First, we derive this function.

At t, agents are randomly matched in groups of \(n\ge 2\). We assume that the random matching process has the following properties: First, the probability with which a given agent is matched with agents of given types equals the product of the proportions of agents of the respective types in the population. Second, the proportion of a given class of grouping is equal to the probability (ex-ante) of such a grouping. The existence of a random matching process with these properties is proved in Alós-Ferrer (1999).Footnote 9

Thus, the proportion of groups containing a number x of A-agents (and \(\left( n-x\right) \) B-agents) is equal to the probability of such a group, i.e. \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) a_{t}^{x}(1-a_{t})^{n-x}\), let \(b(a_{t},x)\) stand for \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) a_{t}^{x}(1-a_{t})^{n-x}\).Footnote 10 This is also the proportion of agents in groups with x A-agents with regard to the initial population (level t) because the groups are composed of equal numbers of agents.

Agents face a stochastic environment that is the same for all members of a particular group. However, the environment of each group is stochastically independent of that of other groups. We categorize all the different possible environments into two types. In a type A environment A-agents outperform B-agents. In a type B environment B-agents outperform A-agents.Footnote 11 The probability of an environment of type \(A\ \)is \(p> \frac{1}{2}\), and that of type B is \((1-p)\).Footnote 12 Therefore, each agent faces an uncertain future environment, but there is no aggregate uncertainty because of our assumptions. Therefore, at each level after the random matching, a proportion p (\((1-p)\)) of the groups has a type A (B) environment. This is assumed to be i.i.d. across levels, so that the probability of an agent facing a given environment is independent of the environment that he/she has faced in the past.

Therefore, the proportion of agents in groups with a number x of A-agents under a type A environment is \(b(a_{t},x)p\). In such groups A-agents outperform B-agents. The system selects the k top-performing agents from each group, where \(k\le n\). The agents selected from each group are the winners of that group. The proportion of winning agents is \(\frac{k}{ n}\) with regard to the initial population (time t). Thus, if a group in a type A environment has more A-agents than vacancies available (i.e. \( x\ge k\)) then all the agents selected from that group are A-agents, and the proportion of A-agents selected is \(\frac{k}{n}b(a_{t},x)p\). However, if \(x<k\) then only a number x of A-agents are selected and some B-agents have to be randomly chosen to fill the \(k-x\) vacancies, so the proportion of A-agents selected is \(\frac{x}{n}b(a_{t},x)p\). Consequently, in this case, the total proportion of A-agents selected will be: \( EA_{t}^{a}=\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{k-1}\frac{x}{n}b(a_{t},x)p+\sum \nolimits _{x=k}^{n}\frac{k}{n}b(a_{t},x)p=\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n}min[x,k]\frac{1 }{n}b(a_{t},x)p\). Analogously, a fraction \((1-p)\) of groups will face a type B environment and similar reasoning applies. In that case, the proportion of A-agents selected comprises the A-agents selected from the groups under the type B environment that do not have enough B-agents to fill all the k vacancies, i.e. \(x-(n-k)\) A-agents: \(EB_{t}^{a}=\sum \nolimits _{x=n-(k-1)}^{n}(x-(n-k))\frac{1}{n}b(a_{t},x)(1-p)\).

The proportion of A-agents selected will be \(EA_{t}^{a}+EB_{t}^{a}\) with regard to the initial population (at t). Finally, the proportion of A-agents is \(\frac{1}{\frac{k}{n}}\left( EA_{t}^{a}+EB_{t}^{a}\right) \) with regard to the population of agents selected. We assume that nonwinners imitate the winning type, so this proportion of A-agents will also be the proportion of the whole population at \(t+1\), i.e., \(a_{t+1}\). Therefore, the dynamic equation has this form:Footnote 13

We use \(S_{[n,k]}\) to denote the system that selects k agents from groups of n agents. We consider the following equilibrium concepts: The point \(a^{*}\in [0,1]\) is said to be a steady state of Eq. (1) if it is a fixed point of f(.), i.e. \(f(a^{*})=a^{*}\). It is obvious that \(f(0)=0\) and \(f(1)=1\). Consequently, \(a=0\) and \(a=1\) are always steady states. The point \(a^{*}\in [0,1]\) is a globally stable equilibrium of (1) if for all \(a_{0}\in \left( 0,1\right) \), \( \lim \nolimits _{t\rightarrow \infty }a_{t}=a^{*}\). The point \(a^{*}\in [0,1]\) is a locally stable equilibrium if only for \( a_{0}\in B(a^{*},\varepsilon )\cap (0,1)\), \(\lim \nolimits _{t\rightarrow \infty }a_{t}=a^{*}\), where \(B(a^{*},\varepsilon )=\{a\in (0,1)/\left| a-a^{*}\right| <\varepsilon \}\) with \(\varepsilon >0 \). Finally, denote \(a^{*}[n,k]\ \)as an inner steady state for the system \(S_{[n,k]}\), i.e. \(a^{*}[n,k]\) belongs to the open interval (0, 1).

In the following section, the dynamics is analyzed and the intuition behind the result is provided.

3 Results

Let \(a^{*}\) be an inner root of the equation \(f(a_{t})-a_{t}=0\) that belongs to the open interval (0, 1). This root exists and is unique if either \(\frac{k}{n}<(1-p)\) or \(\frac{k}{n}>p\) (see the proof of the result below in the “Appendix”). By definition, this root is a steady state. The following result characterizes the dynamic for the selection process specified by Eq. (1).

Proposition 1

Assume \(p>(1-p)\), \(\frac{k}{n}<1\) and consider the dynamic equation (1):

-

(1)

If \(\frac{k}{n}<(1-p)\) there is only one inner steady state \(a^{*}\) and it is globally stable. The steady states \(a=0\) and \(a=1\) are unstable. B-agents survive.

-

(2)

If \(\frac{k}{n}\in [(1-p),p]\) there are no inner steady states. The steady state \(a=0\) is unstable and \(a=1\) is globally stable. A-agents are eventually the only survivors.

-

(3)

If \(\frac{k}{n}>p\) there is only one inner steady state \(a^{*}\), which is unstable and divides the interval \(a\in (0,1)\) into two subintervals. The subinterval \((0,a^{*})\) is the basin of attraction of the steady state \(a=0\) and the subinterval \((a^{*},1)\ \)that of \(a=1\). Both steady states are locally stable. Thus, initial conditions determine whether either A-agent or B-agents are the only survivors.

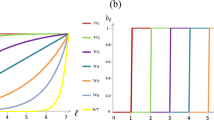

Proposition 1 shows that the equilibrium behavior can be characterized according to rate \(\frac{k}{n}\), which measures the strength of competition in the contest. Note that for low levels of competition (\(\frac{k}{n}>p\)), the selection process is not strong enough to overcome the inertia of the initial population. The dynamic depends on the initial conditions, and the population eventually becomes homogeneous, i.e. either type A or type B: we refer to this case as case L (Low competition). If the strength of competition increases enough (\(\frac{k}{n} \in \left[ (1-p),p\right] \)), the whole population become type A for any initial population. In that case the selection process is strong enough to eventually select only A-agents: we refer to this case as case M (Midrange competition). Finally, if the strength of competition is high enough (\(\frac{k}{n}<(1-p)\)), B-agents also survive: we refer to this case as case H (High competition). Figure 1 shows a phase diagram of each case. Therefore, no matter how low the expected success rate of a type of agent is, if the strength of competition is high enough agents of that type survive in the long run.

3.1 Discussion and intuition of the main result

To understand why this happens, it must first be observed that the dynamic of the system depends on the probability of each type of agent winning.Footnote 14 For example, if the system is in a period t and the probability of an A-agent being selected is greater than that of a B-agent, then the proportion of A-agents in period \(t+1\) is greater than in t, i.e. the proportion of A-agents increases and the proportion of B-agents decreases. Now, focus on a particular type of agent who faces one of the two following extreme scenarios:

-

If agents of this particular type are scarce (say close to extinction) they will generally be matched with agents of the other type.Footnote 15 Thus, in general, there will only be one agent of this particular type in a group, who will only be selected if he/she outperforms the other type of agents so that he/she is the top performer. In such a context, the probability of this particular type of agent winning is not influenced by an increase in the strength of competition. His/her probability of winning depends almost entirely on his/her probability of outperforming the other type, i.e. it is p if the agent is type A and \((1-p)\) otherwise.

-

However, when agents of this particular type abound (say the other type is close to extinction), an agent of this particular type will generally be matched with agents of his/her own type (see footnote 15). Thus, if all the agents in a group are of the same type, they respond in the same way to the same environment. They all perform equally. The competitors of a particular agent in his/her own group are as successful (or unsuccessful) as he/she is. Thus, selection does not depend at all on the performance of this particular type of agent: the probability of winning depends almost entirely on how many people are selected. Therefore, the probability of this particular type of agent winning is strongly influenced by an increase in the strength of competition.

Therefore, an increase in the strength of competition tends to punish the more common type of agents because it decreases their probability of winning, but does not affect the relatively scarce type. If competition is high enough, no one type can be abundant enough to be the only survivor. Thus, diversity can be favored or punished by tuning the strength of competition.

To obtain a clearer picture, consider the following particular case. Assume that the dynamic of the model is case M. In that case, the only global equilibrium is the whole population being type A (\(a^{*}=1\)). Consequently, for any state of the system \(a_{t}\), the probability of A-agents winning is greater than that of B-agents. The rest of the discussion focuses on states in which \(a_{t}\simeq 1\). When \(a_{t}\simeq 1\), as mentioned above, the probability that an A-agent (abundant type) will win is approximately equal to the proportion of agents selected (\(\frac{k}{n} \)), and the probability that a B-agent (scarce type) will win is approximately equal to the probability of success of that type (\((1-p)\)). Obviously, if the dynamic is case M, then \(\frac{k}{n}>(1-p)\). However, if \(\frac{k}{n}\) is reduced (competition increases), the probability of winning of an A-agent decreases, while the probability of winning of a B -agent remains practically unchanged. Therefore, if \(\frac{k}{n}\) decreases beyond \((1-p)\) the probability of winning of B-agents is greater than that of A-agents, and the proportion of A-agents will decrease in the next period. When this happens the homogeneous equilibrium \(a^{*}=1\) becomes unstable, and the system converges to a stable globally mixed equilibrium in which there are agents of both types. The dynamic changes from case M to case H.

On the other hand, it can be shown by a similar argument that if \(\frac{k}{n} \) increases beyond p, the state \(a=0\) becomes locally stable. In that case, for states of the system close to \(a=0\), the probability of winning for B-agents is greater than for A-agents. In addition, the state \(a=1\) changes from globally to locally stable, and the dynamic changes from case M to case L. The lower the strength of competition of a system, the easier it is for it to be dominated by one type of agent and for it to achieve homogeneity.

Therefore, if competition increases two forces work together: On the one hand, the more important an agent’s success or failure in the selection becomes and thus the less the effect of the initial proportions of the different types of agent matters. On the other hand, an increase in the strength of competition tends to punish the more common type of agents because it decreases their probability of winning, but it does not affect that of the scarcer type. Thus, competition can encourage diversity.

It would be fair to ask how robust the results would be if the population were finite. In this case, the dynamics would be a complex stochastic system. The probability of a particular group of n individuals with x being A-agents being formed could be calculated. However, the process is stochastic, and this particular group might or might not eventually be created. Thus, it cannot be assumed that the frequency of different matches can be identified with their corresponding expectations. However, if the population increases the number of groups created also increases, so the probability of either group having representatives among the groups eventually created increases. The proportion of any kind of group can be expected to approach its expected value as the population becomes very large. The average behavior of this finite stochastic model should approach our continuous deterministic model as the population increases. In any event, the process continues to be stochastic. See Boylan (1995) for a study of this issue. However, more interesting for checking the robustness of our model is the fact that the intuition explained above for the continuous model would also apply to this finite model. If B-agents are close to extinction (say only one remains in the population), that B-agent will be matched with \(n-1\) A-agents. The only chance for him/her to be promoted is for the environment to be type B, the probability of which is \((1-p)\). Thus, his/her probability of promotion only depends on his/her expected success rate. However, if the population is large enough the probability of an A-agent being matched only with A-agents is almost one. Thus, the probability of promotion will be \(\frac{k}{n}\), and it does not depend on his/her expected success rate. Therefore, if \(\frac{k}{n}<(1-p)\) on average the population of B-agents should survive more often than not.

In the following section we seek to obtain more insights about the behavior of the inner steady state. To that end two specific values of k are considered. First, k is taken to be 1 and then it is considered to be a function of parameter n, i.e. \(k=n-1\). This enables us to obtain a closed form of Eq. (1). Thus, changes in the strength of competition only depend on parameter n, so the behavior of the inner steady state can be studied more easily. With \(k=1\), midrange and high strength competition is analyzed, and with \(k=n-1\) the midrange and low cases are analyzed.

3.2 Low and midrange competition

In this section, \(k=n-1\) is assumed and only one agent of each group is not selected. We consider \(S[n,k=n-1]\). Nevertheless, a wide range of degrees of competition can be considered. As mentioned above, the strength of competition is characterized by the quotient \(\tfrac{k}{n}\), which is now \( \frac{n-1}{n}\in \left\{ \frac{1}{2},\frac{2}{3},\frac{3}{4},\ldots ,1\right\} \) . Thus, an increase in n decreases the strength of competition because the fraction \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{n-1}{n}\) increases. As \((1-p)\) is smaller than \( \frac{1}{2}\), it must hold that \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{n-1}{n}>(1-p)\). Thus, by Proposition 1 only cases M and L can occur. When \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{n-1}{n}>p\) case L arises and there is an unstable inner steady state. Let \(a^{*}[n,k=n-1]\) be that steady state. However, with \(\frac{n-1}{n}<p\) there is no inner steady state ( case M) and the globally stable equilibrium is \(a^{*}=1\).

The following result shows that \(a^{*}[n,k=n-1]\) is increasing in n. The proof is in the “Appendix”.

Proposition 2

If \(\frac{n-1}{n}>p\), then \(a^{*}[n,k=n-1]<a^{*}[n+1,k=n]\).

With a low competition (case L), if the strength of competition increases (n decreases) enough, the inner steady state decreases to zero (increasing the basin of attraction of \(a=1\) and decreasing that of \(a=0\)), and \(a=1\) eventually becomes globally stable. In Fig. 1 the inner steady state of case L moves to the left, and the case shifts from L to M. As mentioned above, in that case an increase in competition increases the importance of an agent’s success or failure in the selection, and the effect of the initial proportions of the different types of agent becomes less important.

The following result shows how \(a^{*}[n,k=n-1]\) changes with the gap between the success rates \(p-(1-p)\) as expected. The proof is in the “Appendix”.

Proposition 3

Let \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{n-1}{n}>p\), if p increases, the inner steady state \(a^{*}[n,k=n-1]\) decreases.

The greater the gap between the success rates is (p increases), the greater the advantage of a type A agent is. With low-level competition (case L), an increase in p decreases the inner steady state. In Fig. 1, the inner steady state of case L moves to the left, and this causes a decrease in the basin of attraction of \(a=0\).

3.3 High and midrange competition

In this section, assuming \(k=1\), only one agent of each group is selected and we consider \(S[n,k=1]\). The strength of competition is characterized by \( \frac{k}{n}=\frac{1}{n}\in \left\{ 0,\ldots ,\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{2} \right\} \). Thus, by Proposition 1 only cases H and M can be found. Let \(a^{*}[n,k=1]\) be the unique globally stable steady state, which is one in case M, i.e. when \(\frac{1}{n} \in [1-p,\frac{1}{2}]\) and is smaller than one in case H, \( \frac{1}{n}\in (0,1-p]\). The following result shows that \(a^{*}[n,k=1]\) is decreasing in n. The proof is in the “Appendix”.

Proposition 4

If \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{1}{n}<1-p\), then \(a^{*}[n,k=1]>a^{*}[n+1,k=1]\).

Therefore, with midrange competition (case M), if competition increases (n increases) enough, the steady state \(a^{*}=1\) loses its stability and an inner state that is globally stable appears. The case shifts from M to H, and the B-agents also survive. As the strength of competition increases this inner steady state decreases and the proportion of B agents in equilibrium increases. In Fig. 1 the inner steady state of case H moves to the left. As already mentioned, in such cases competition can encourage diversity. The strength of competition tends to punish the more common type of agent but does not affect scarcer type.

The following result shows how \(a^{*}[n,k=1]\) changes with the gap between the success rates \(p-(1-p)\) as expected. The proof is in the “Appendix”.

Proposition 5

Let \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{1}{n}<(1-p)\), if p increases, the globally stable inner steady state \(a^{*}[n,k=1]\) increases.

With high competition (case H) and increases in p there is an increase in the globally stable inner steady state \(a^{*}[n,k=1]\). In Fig. 1 the inner steady state of case H moves to the right, and the proportion of B agents decreases in equilibrium. If the increase in p is high enough the case can shift from H to M.

4 Time of convergence and numerical analysis

An institution could be concerned not only about the final outcome but also about how fast the goal is reached. We have carried out a numerical analysis to study the convergence times. In this section we present our findings, which are summarized in Table 1.

We find that convergence time can increase for several reasons. First, it decreases as the proportion of the population selected decreases, i.e. as k / n decreases. As expected, if competition is not high, and consequently most of the population are selected, the selection process slows down, see for example the column of \(n=25\) for \(p=0.55\) in Table 1. However, there are other reasons that can slow down the process.

The process can become very slow when the level of competition is close to the thresholds that mark the boundaries between the case H, M and L. These three cases are shown respectively in bold, italic, and roman in Table 1. In other words, this slowdown occurs when the level of competition k / n is close to the expected success rate of either agent type A or type B. Note that the difference between the three cases is that a steady state changes its stability; this means that when k / n is very close to one of these boundaries the function \(a_{t}+1=f\left( a\right) \) is also very close to the diagonal line \(a_{t}+1=a_{t}\). Consequently, the changes in the population are minimal in each interaction. On the boundary between case M and L this effect does not appear in Table 1. This is because in case L there are two locally stable equilibria and two basins of attraction. In addition, the initial condition considered is in the basin of attraction of \( a^{*}=1\) and the slowdown of the process appears in the basin of attraction of \(a^{*}=0\). In any event, case L should be the least interesting for the institution because the outcome depends on the initial conditions.

5 Conclusion

This paper analyzes the strength of competition in a simple dynamic contest model. The dynamic depends on the probability of winning of each type of agent, which in turn depends on three factors: First on the composition of the population, i.e. the proportion of agents of each type; second on how strong the competition is; and third on the probability of success in the activity undertaken by agents within the organization. We find that as competition increases the initial conditions becomes less relevant, so for an intermediate level of competition the best performing agents are the only survivors. However, if competition is sufficiently strong the agents with the lowest expected success rate also survive, no matter how low their expected success rate is. Too much competition is always harmful to the best performers. An increase in competition tends to punish the more common type of agent because it decreases their probability of winning, but it does not affect the relatively scarce type. Consequently, care must be taken with the strength of competition. As we show, if there is a desire to increase the presence in a population of certain agents with a high expected success rate then in certain contexts it may be necessary to decrease the strength of competition rather than to increase it. By contrast, competition may have to be increased if the objective is to increase the presence of low-performing agents in the sense defined in this paper.

Note that if a model with more than two types of agents with different expected success rates is considered the agent with the lowest rate will always survive for a sufficiently high level of competition. In addition, for a sufficiently low level of competition any homogeneous state (the whole population is of the same type) will be a locally stable steady state. The intuition discussed in Sect. 3 also applies to this more general case.

The selection system considered makes sense if the institution cannot select agents by type and the alternative is to use a selection process based on the performance of agents. On the other hand, the selection of B-agents may or may not be desirable depending on the nature of the situation and the preferences of the institutions involved.

Our result depends largely on one particular critical assumption: in a group, all agents of the same type are either better or worse than other types simultaneously, so their successes (or failures) perfectly correlate with one another. If two agents are under the same environment and are following the same rule and one of them is successful, then the other will also be successful, or at least more successful than other types. If that is the case, the strength of competition will have this paradoxical effect in the dynamic of the process. In a real institution, this paradoxical effect should be more noticeable as this correlation becomes stronger.

Notes

Note that the prizes can be very diverse, for example a promotion, a job opportunity, a contract, a sale, etc.

As a stylized example, the behavioral rules (A and B) can be thought of as different available technologies: one of them is better more often than the other, and agents are proficient in either technology A or B. Another stylized example could be a sales company that promotes people according to their success in selling. The company employs men and women and men sell better to men and women sell better to women. If the potential market has more men than women, men could be the A-agents and women the B-agents. It is not easy to find an application that fits all of the model’s elements because the model seeks to represent a family of complex institutions in a very stylized manner to point out a very specific characteristic of a selection process. Obviously, in any real institution the selection process is influenced by many more factors. However, we believe that the properties identified in our model are robust enough to play a role in more complex situations.

We assume that the institution cannot either impose the strategy to be followed by an agent or observe the type of agent, so we consider that each individual interacts with randomly selected individuals. Thus, the institution can only determine the size of the group n and the number of prizes k, i.e., the ratio \(\frac{k}{n}\).

“To win” and “to be selected” are used interchangeably in this paper.

An equivalent assumption is that only the winners at t are considered for competition at \(t+1\), thus, the nonwinners are out of the contest.

Notice that in this case (\(x<k\) and the environment is A), there are only x agents of type A in a group, and in addition they are all successful. The rest of the agents in the group are type B and some change to A but others do not.

We could consider the level of conformity mentioned above instead of the strength of competition. In that case, we obtain that for high levels of conformity case L pertains, if the conformity requirement is intermediate case M pertains and for low levels case H pertains.

For any objective function of the institution, there will be an optimal proportion of A-agents, which could vary from 0 to 1. The institution should take the appropriate k and n to attain its objective.

Alós-Ferrer (1999) gives a constructive existence proof for the case \( n=2 \). The generalization to groups of n agents is straightforward.

The x is distributed as a binomial distribution, \(x\sim B(n,a_{t})\).

One further kind of environment can be considered in which both rules perform equally. This environment adds no new insights to the analysis, so we do not consider it.

This probability p and \((1-p)\) can also be seen as the expected success rates of an agent of type A and B respectively.

We do not actually need to consider the sum from \(x=0\); it suffices to start at \(x=1\). This is because groups with \(x=0\) contain no type A; in those groups only type B can survive, independently of k. This also applies to \(f^{^{\prime }}(a)\) and \(f^{^{\prime \prime }}(a)\). It seems convenient to include this in the expressions only for symmetry with the term where \(x=n\). In addition, \(\Psi \left( x,k,p,n\right) \) stand for \(\frac{\left( Min[x,k]p+Max[x-(n-k),0](1-p)\right) }{k}\).

Let \(P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (A)}}\)(\(P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (B)}}\)) be the probability of an A(B)-agent being selected in period t. Notice that \( a_{t+1}=\tfrac{\text {A-agents selected}}{\text {agents selected}}=\tfrac{ a_{t}P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (A)}}}{a_{t}P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (A)} }+b_{t}P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (B)}}}=\tfrac{a_{t}P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (A) }}}{\frac{k}{n}}\Leftrightarrow P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (A)}}=\tfrac{a_{t+1} }{a_{t}}\frac{k}{n}\), analogously \(P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (B)}}=\tfrac{ b_{t+1}}{b_{t}}\frac{k}{n}\). Therefore, \(P_{{\small t}}^{{\small (A)}}>P_{ {\small t}}^{{\small (B)}}\Leftrightarrow \tfrac{a_{t+1}}{a_{t}}>\tfrac{ b_{t+1}}{b_{t}}\Leftrightarrow \tfrac{a_{t+1}}{a_{t}}>\tfrac{(1-a_{t+1})}{ (1-a_{t})}>0\Leftrightarrow a_{t+1}>a_{t}\).

This happens with a probability close to one.

For example, expression (9): \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x+1\end{array}}\right) =\frac{n!}{ (x+1)!(n-x-1)!}=\frac{n!}{(x+2)!(n-x-2)!}\frac{x+2}{n-x-1}=\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x+2\end{array}}\right) \frac{x+2}{n-x-1}\).

It can be also zero if \(x=\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2}\right\rfloor =\frac{k}{2}\). However the rationale is the same. Where \(\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2} \right\rfloor \) gives the highest integer less than or equal to \(\frac{k}{2}\).

It is possible in difference equations for a solution not to be a steady point. Thus, point b is called a periodic point of \( x_{t+1}=f(x_{t})\) if \(f^{k}(b)=b\) for a positive integer k, i.e. b is again reached after k iterations. See Elaydi (1996).

The function g(a) must be decreasing at \(a=\hat{a}\), because it is positive to the left side, negative to the right, and continuous.

Note that \(\Psi \left( x,k,p,n\right) \) is independent of a and \(\frac{ \partial b(a,x)}{\partial a}=\frac{x-na}{a(1-a)}b(a,x)\).

The first derivative of g(a) is the sequence of the derivatives of each term of g(a). It is necessary to simplify the expression to obtain the properly defined derivative function.

The second derivative of g(a) is the sequence of the second derivatives of each term of g(a). It is necessary to simplify these terms to obtain the properly defined derivative function.

As mentioned above \(\Psi \left( x,k,p,n\right) \) is independent of a and \( \frac{\partial ^{2}b(a,x)}{\partial a^{2}}=\frac{\left( x-an\right) (x-(n-1)a)-x(1-a)}{a^{2}(1-a)^{2}}b(a,x)\).

See footnote 18.

In any event, even if \(g(a_{t})\) was negative there would be no periodic points.

It can be also zero if \(x=\left\lfloor an\right\rfloor =an\). However the rationale is the same.

By Claim 6, \(\tilde{a}>\frac{1}{2}\). Thus, we only need to prove that \(\frac{d}{d\tilde{a}}\left( \frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a} ^{n}}{(1-\tilde{a})-(1-\tilde{a})^{n}}\right) >0\) for \(\tilde{a}>\frac{1}{2}\) . However, as the proof of Proposition 3 is omitted because it is analogous with \(\tilde{a}<\frac{1}{2}\), we consider both cases.

References

Alós-Ferrer C (1999) Dynamical systems with a continuum of randomly matched agents. J Econ Theory 86:245–267

Azmat G, Möller M (2009) Competition among contests. RAND J Econ 4:743–768

Boylan RT (1992) Laws of large numbers for dynamical systems with randomly matched individuals. J Econ Theory 57:473–504

Boylan RT (1995) Continuous approximation of dynamical systems with randomly matched individuals. J Econ Theory 667:615–625

Duffie D, Sun Y (2012) The exact law of large numbers for independent random matching. J Econ Theory 147:1105–1139

Elaydi S (1996) An introduction to difference equations. Springer, New York

Garcia-Martinez JA (2010) Selectivity in hierarchical social systems. J Econ Theory 145:2471–2482

Groh C, Moldovanu B, Sela A, Sunde U (2012) Optimal seedings in elimination tournaments. Econ Theory 49:59–80

Harrington JE (1998) The social selection of flexible and rigid agents. Am Econ Rev 88:63–82

Harrington JE (1999a) Rigidity of social systems. J Polit Econ 107:40–64

Harrington JE (1999b) The equilibrium level of rigidity in a hierarchy. Games Econ Behav 28:189–202

Harrington JE (2000) Progressive ambition, electoral selection, and the creation of Ideologies. Econ Gov 1:13–23

Harrington JE (2003) Fluidity of social norms in a hierarchical system. In: Kollman K, Miller J, Page S (eds) Computational models in political economy. The MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 49–84

Hvide HK, Kristiansen EG (2002) Risk taking in selection contests. Games Econ Behav 42:172–179

Lazear E, Rosen S (1981) Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. J Polit Econ 89:841–864

Rosen S (1986) Prizes and incentives in elimination tournaments. Am Econ Rev 76:701–715

Tsoulouhas T, Knoeber CR, Agrawal A (2007) Contests to become CEO: incentives, selection and handicaps. Econ Theory 30(2):195–221

Vega-Redondo F (2000) Unfolding social hierarchies. J Econ Theory 90:177–203

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I wish to express my gratitude to Fernando Vega-Redondo, Ascensión Andina-Díaz, Carlos Alós-Ferrer, Ana Ania, Pablo Beker, Joseph Harrington, Francisco Marhuenda, Dilip Mookherjee, Frédéric Palomino, and Giovanni Ponti for their helpful comments and suggestions. I also thank the Editor Juan D. Moreno-Ternero and two anonymous referees for their insightful comments. I also acknowledge contributions by participants at seminars and conferences at Alicante, Bilbao, Boston, Marseilles, and Ankara. Financial support from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad through Project MTM2014-54199-P and the Junta de Andalucía through Project SEJ2011-8065 is gratefully acknowledged.

A. Appendix

A. Appendix

First, some preliminary results are shown. Then the propositions are proved in the following order: first proposition 1, then 4, 5, 2, and 3.

Assume \(\frac{1}{2}<p<1\), \(k\in \mathbb {N} \), \(n\in \mathbb {N} \), \(k>0\), \(n>k\ge 2\), \(a_{t}\in [0,1]\), and the time subscript is omitted wherever it is not confusing to do so. Let b(a, x) stand for \( \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) a^{x}(1-a)^{n-x}\).

1.1 A.1 Preliminary results

It is helpful to write down some basic results that are widely used in the proof of the propositions.

The binomial theorem

The corollary

The following expressions are directly derived from the factorial formulaFootnote 16 \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) =\frac{n!}{x!(n-x)!}\).

The following results are also used in the proofs of the propositions.

Claim 1

For any k and n, \(\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) =\sum \nolimits _{x=n-(k-1)}^{n}(x-(n-k))\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) \)

Proof

By the symmetry of the binomial coefficient, \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) {\small =}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n \\ n-x\end{array}}\right) \). Therefore,

\(\square \)

Claim 2

For any k and n,

Proof

Since \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n-1\\ n\end{array}}\right) =0\), the above expression is equal to \(n-n\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n-1}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n-1\\ x\end{array}}\right) a^{x}(1-a)^{n-1-x}(1-a)=n-n(1-a)=an\) \(\square \)

Let z(.) stand for \(b(a,x)\left( \left( an-2x\right) a(n-1)+x(x-1)\right) \)

Lemma 1

Let \(\ h\ \) be an integer and \(0<h\le n\), then,

\(\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{h}z(.)=(1-a)^{n-h}a^{h+1}(a(n-1)-h)(h+1)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ h+1\end{array}}\right) \)

Proof

This is proved by induction on h. If \(h=1\):

It is proved that it holds for \(h+1\) if it holds for h:

The last expression is equal to \((1-a)^{n-h}a^{h+1}(a(n-1)-h)(h+1)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ h+1\end{array}}\right) \) but in \(\left( h+1\right) \) instead of h. \(\square \)

Lemma 2

Let\(\ h\ \) be an integer and \(0<h\le n\), then,

Proof

The proof is analogous to the lemma above, and it is also proved by induction on h.

If \(h=1\):

It is proved that it holds for \(h+1\) if it holds for h:

[using expression (9)]

The last expression is equal to \((1-a)^{n-h}a^{h+1}(an-h-1)(h+1)h\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ h+1\end{array}}\right) \) but in \(\left( h+1\right) \) instead of h. \(\square \)

Lemma 3

The function g(a) in \(a=\frac{1}{2}\) is greater than zero, i.e., \(g(\frac{1}{2})=f(\frac{1}{2})-\frac{1}{2}>0\)

Proof

The Eq. (1) evaluated in \(a=\frac{1}{2}\) and minus \(\frac{1}{2}\) is \(g(\frac{1}{2})=f(\frac{1}{2})-\frac{1}{2}=\left( \sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n}\frac{ min[x,k]}{k}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+\sum \nolimits _{x=n-(k-1)}^{n}\frac{(x-(n-k))}{k} \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)\right) \left( \frac{1}{2}\right) ^{n}-\frac{1}{2}>0\) \(\Leftrightarrow \sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n}min[x,k]\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+\sum \nolimits _{x=n-(k-1)}^{n}(x-(n-k))\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)-\frac{1}{2}k2^{n}>0\)

(using Claim 1)

\(\Leftrightarrow \sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}min[x,k]\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)-\frac{1}{2}k2^{n}>0\)

\(\Leftrightarrow \sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}x\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+k\sum \limits _{x=k+1}^{n} \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)-\frac{1}{2} k2^{n}>0 \)

\(\Leftrightarrow \sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}x\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+k\left( \sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) -\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) \right) p+\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)-\frac{1}{2}k2^{n}>0\)

[using (3)]

\(\Leftrightarrow \sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}x\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+k\left( 2^{n}-\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) \right) p+\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)-\frac{1}{2}k2^{n}>0\)

\(\Leftrightarrow \sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}x\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p-k\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k} \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)+kp2^{n}-\frac{1}{2} k2^{n}>0\)

\(\Leftrightarrow -\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)p\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) +\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)+kp2^{n}-\frac{1}{2}k2^{n}(p+(1-p))>0\)

\(\Leftrightarrow -\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) p+\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) (1-p)+\frac{1}{2}k2^{n}p-\frac{1}{2} k2^{n}(1-p)>0\)

\(\Leftrightarrow \left( \frac{1}{2}k2^{n}-\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n \\ x\end{array}}\right) \right) \left( p-(1-p)\right)>0\Leftrightarrow \left( \frac{1}{2} k2^{n}-\sum \limits _{x=0}^{k}(k-x)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) \right) {>}0\)

[using (3)]

Obviously, \(\frac{k}{2}\sum \nolimits _{x=k+1}^{n}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) >0\). The expression \(\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{k}\left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) \) is also positive. First note that \(\left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \) is negativeFootnote 17 for \(0\le x\le \left\lfloor \frac{k}{2}\right\rfloor \) and positive for \(\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2}\right\rfloor <x\le k\). In addition, the value of \( \left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \) for \(x=i\) is equal to \(x=k-i\) in absolute value; the values are symmetrical. Second, \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) \) takes increasing values from \(x=0\) to \(x=\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor \), and then it decreases symmetrically. As \(\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2}\right\rfloor <\left\lfloor \frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor \), the sum of the positive terms has to be greater than the sum of the negative terms in absolute value:

\(\left( \sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}\left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right)>0\right) \Leftrightarrow \left( \sum \limits _{x=0}^{\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2} \right\rfloor }\left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) +\sum \limits _{x=\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2}\right\rfloor +1}^{n}\left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n \\ x\end{array}}\right) >0\right) \)

\(\Leftrightarrow \left( \sum \limits _{x=\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2}\right\rfloor +1}^{n}\left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) >-\sum \limits _{x=0}^{\left\lfloor \frac{k}{2}\right\rfloor }\left( x-\frac{k}{2}\right) \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ x\end{array}}\right) \right) \) \(\square \)

Claim 3

For any n and a,

Proof

By Claim 2 and using (2) \(\sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}b(a,x)(x-an)=\sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}xb(a,x)-an\sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}b(a,x)=an-an=0\) \(\square \)

1.2 A.2 Proof of Proposition 1.

The dynamic of \(S_{[n,k]}\) is given by Eq. (1):

It is useful to start by presenting an outline of the proof. First it is shown that the function \(g(a)=f(a)-a\) is continuous in \(a=[0,1]\) with \( g(0)=g(1)=0\). Second, local stability in the steady states \(a=0\) and \(a=1\) is studied by means of the first derivative of g(a). Thus, it is shown that if \(\frac{k}{n}<(1-p)\) the states \(a=0\) and \(a=1\) are unstable because \( g^{\prime }(0)>0\) and \(g^{\prime }(1)>0\); if \(\frac{k}{n}\in \left[ (1-p),p \right] \), then \(a=0\) is unstable and \(a=1\) is locally stable because \( g^{\prime }(0)>0\) and \(g^{\prime }(1)<0\); if \(\frac{k}{n}>p\), then \(a=0\) and \(a=1\) are locally stable because \(g^{\prime }(0)<0\) and \(g^{\prime }(1)<0\). Third, it is proved that g(a) has no more than one inner root. Fourth, it is proven that there are no periodic points.Footnote 18

With all these results, the proposition can be easily proved in the following way. First, the function g(a) is continuous with no more than one inner root in \(a=\left( 0,1\right) \), and \(g(0)=0\) and \(g(1)=0\). Second, if \(\frac{k}{n}<(1-p)\), then \(g^{\prime }(0)>0\) and \(g^{\prime }(1)>0\), so g(a) must have at least one root, but as it cannot be possible for it to have more than one g(a) necessarily has a unique inner root \(\hat{a}\). As \( g^{\prime }(\hat{a})\) is necessarily negative,Footnote 19 that inner root is a stable steady state. As \(g(a)>0\) if \(a\in \left( 0,\hat{a} \right) \) and \(g(a)<0\) if \(a\in \left( \hat{a},1\right) \), and there are no periodic points, this inner root is a globally stable steady state and the other two steady states (\(a=0\) and \(a=1\)) are unstable. Third, if \(\frac{k}{n }\in \left[ (1-p),p\right] \) then \(g^{\prime }(0)>0\) and \(g^{\prime }(1)<0\), so the minimum number of roots compatible with this case is two, which is not possible. Therefore there cannot be any inner roots, and \(g(a)>0\) for all \(a\in (0,1)\). Fourth, if \(\frac{k}{n}>p\), then \(g^{\prime }(0)<0\) and \( g^{\prime }(1)<0\), so g(a) necessarily has a unique inner root \(\hat{a}\in \left( 0,1\right) \) with \(g(a)<0\) if \(a\in \left( 0,\hat{a}\right) \) and \( g(a)>0\) if \(a\in \left( \hat{a},1\right) \). This inner root is an unstable stable steady state, and the other two steady states (\(a=0\) and \(a=1\)) are locally stable. This completes the proof.

It is straightforward to show that g(a) is continuous because f(a) is a polynomial. In addition, it is obvious that \(f(0)=0\) and \(f(1)=1\), so \( g(0)=g(1)=0\).

Using Eq. (1), it is straightforward to show that the first derivative of \(g(a)=f(a)-a\) is:Footnote 20

If \(a=0\) the terms of the series \(g^{\prime }(a)\) are equal to zero except for \(x=1\).Footnote 21

\(\left( g^{\prime }(0)=\frac{p}{k}n-1\ge 0\right) \Longleftrightarrow \left( \frac{k}{n}\le p\right) \)

If \(a=1\) the terms of the series \(g^{\prime }(a)\) are equal to zero except for \(x=n-1\) and \(x=n\).

\(g^{\prime }(1)=\frac{kp+(k-1)(1-p)}{k}n(-1)+\frac{kp+k(1-p)}{k}n-1=\frac{n}{ k}(1-p)-1\ge 0\Longleftrightarrow \left( \frac{k}{n}\le (1-p)\right) \)

To prove that \(g(a)=0\) has no more than one inner root in \(a\in (0,1)\), it suffices to show that g(a) has no more than one inflection point in \(a\in (0,1)\ \)since \(g(0)=g(1)=0\) and \(f^{\prime }(a)\) is continuous in (0, 1). The following Claim gives a close form of the second derivative, \(g^{\prime \prime }(a)\).

Claim 4

The function \(g^{\prime \prime }(a)=f^{\prime \prime }(a)=-(k+1)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ k+1\end{array}}\right) (1-a)^{-k-1}a^{-k-1}(p(1-a)^{n}a^{2k}-(1-p)(1-a)^{2k}a^{n})\)

Proof

It is straightforward to show that the second derivativeFootnote 22 of g(a) is:Footnote 23

Where if \(z(.)=b(a,x)\left( \left( an-2x\right) a(n-1)+x(x-1)\right) \),

\(g^{\prime \prime }(a)=\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n}\Psi \left( x,k,p,n\right) \frac{ z(.)}{a^{2}(1-a)^{2}}\)

First, we rewritten this functions depending on \(\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{h}z(.)\) and \(\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{h}xz(.)\), thus, we will be able to apply Lemmas 1 and 2 to simplify the expression.

Notice that, from Lemmas 1 and 2 with \( h=n \), \(\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n}z(.)=\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n}xz(.)=0\) because \( \left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ n+1\end{array}}\right) =0\), thus:

By Lemmas 1 and 2 with \(h=k\), after some algebra, the first term of (11) above is

\(\frac{\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{k}x\text { }z(.)p-k\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{k}z(.)p}{ ka^{2}(1-a)^{2}}=-(1-a)^{n-k-1}a^{k-1}(k+1)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ k+1\end{array}}\right) p\)

and by Lemmas 1 and 2 with \(h=n-k\), after some algebra, the second term of (11) is:

\(\frac{\left( \sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n-k}x~z(.)-(n-k)\sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n-k}z(.)\right) (1-p)}{ ka^{2}(1-a)^{2}}=-\frac{(1-p)(1-a)^{k-1}a^{(n-k)-1}(n-k)((n-k)+1)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ n-k+1\end{array}}\right) }{k}\)

[using expression (9)]

\(=-\frac{(1-p)(1-a)^{k-1}a^{(n-k)-1}(n-k)((n-k)+1)\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ k+1\end{array}}\right) \frac{(k+1)k }{(n-k)(n-k+1)}}{k}=-(1-p)(1-a)^{k-1}a^{(n-k)-1}\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ k+1\end{array}}\right) (k+1)\)

Therefore,

\(\blacklozenge \)

We now show that there is no more than one inflection point in \(a\in (0,1)\). First, note that if \(\bar{a}\) is an inflection point, then \(g^{\prime \prime }(\bar{a})=0\). Thus, by Claim 4,

Therefore, the Eq. (12) can have only one real root in the interval \(a\in (0,1)\). Consequently, there is no more than one inflection point in \(a\in (0,1)\), which means that the function g(a) has no more than one root in \(a\in (0,1)\).

Before concluding, it is proved that there are no periodic points.Footnote 24 It has been proved that the function \(g(a_{t})\) has either one inner root or none, i.e. there is only one inner steady state in (0, 1) or none at all. If it has none, the function \(g(a_{t})\) is necessarily positive,Footnote 25 so there are obviously no periodic points because \(a_{t}<a_{t+1}\) for all \(a_{t}\in (0,1)\). If there is one steady state in (0, 1) any possibility of there being periodic points completely disappears if the function \(f(a_{t})\) is increasing. Note that if \(f(a_{t})\) is increasing, then for all \(a_{t}\) equal to or greater than the inner steady state (\(\hat{a }\)) either \(a_{t}<a_{t+1}\) for all \(a_{t}\in (\hat{a},1)\) or \(a_{t}>a_{t+1}\) for all \(a_{t}\in (\hat{a},1)\), and always \(a_{t+1}\ge \hat{a}\) for any \( a_{t}\in (\hat{a},1)\). Thus, it suffices to prove that the function \( f(a_{t}) \) is increasing. The following claim is needed to prove that \( f^{\prime }(a_{t})>0\). \(\square \)

Claim 5

Let the function \(r(x)=b(a,x)(x-an)\) and h(x) be a positive function and increasing in x. Then \( \sum \nolimits _{x=0}^{n}h(x)r(x)>0\)

Proof

The expression \(b(a,x)(x-an)\) is negativeFootnote 26 if \(x\le \left\lfloor an\right\rfloor \) and positive if \(x>\left\lfloor an\right\rfloor \). Where \(\left\lfloor an\right\rfloor \) gives the highest integer less than or equal to an. By Claim 3,

As \(h(x)>0\) is a function increasing in x,

\(\left( -\sum \limits _{x=0}^{\left\lfloor an\right\rfloor }h(x)r(x)<\sum \limits _{x=\left\lfloor an\right\rfloor +1}^{n}h(x)r(x)\right) \iff \left( \sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}h(x)r(x)>0\right) \qquad \qquad \qquad \blacklozenge \)

That \(f^{\prime }(a_{t})>0\) is now proved. From expression (10),

\(f^{\prime }(a_{t})=\sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}\Psi \left( x,k,p,n\right) b(a,x) \frac{x-na}{a(1-a)}>0\iff \sum \limits _{x=0}^{n}\Psi \left( x,k,p,n\right) b(a,x)\left( x-na\right) >0\)

It is straightforward to show that the expression \(\Psi \left( x,k,p,n\right) \ \)takes values in [0, 1] and is increasing in x. Therefore, by Claim 5, \(f^{\prime }(a_{t})>0\), and \(f(a_{t})\) is increasing. Periodic points are therefore not possible.

It can be concluded that:

-

(1)

If \(\frac{k}{n}<(1-p)\) then \(g^{\prime }(0)>0\) and \(g^{\prime }(1)>0\). Thus, on the one hand, the function g(a) is continuous and \(g(0)=g(1)=0\). On the other hand g(a) is positive around \(a=0\) and negative around \(a=1\). Consequently, by Bolzano’s Theorem there is at least one inner root. It has been proved that there cannot be more than one inner root. Therefore, there is only one inner root \(a^{*}\) and it is globally stable.

-

(2)

If \(\frac{k}{n}\in [(1-p),p]\) then \(g^{\prime }(0)>0\) and \( g^{\prime }(1)<0\). In that case, as \(g(0)=g(1)=0\), the function g(a) is positive around \(a=0\) and around \(a=1\). There cannot be more than one inner root, so the function g(a) must be positive for \(a\in (0,1)\). The only possibility of having an inner point is for the inner point to be a minimum of the function, so that the function would be positive for \(a\in (0,1)\). However, this is not possible because there is no more than one inflection point. Therefore, there is necessarily no inner root. The steady state \(a=0\) is unstable, and the steady state \(a=1\) is globally stable.

-

(3)

If \(\frac{k}{n}>p\), then \(g^{\prime }(0)<0\) and \(g^{\prime }(1)<0\). In that case, as \(g(0)=g(1)=0\), the function g(a) is negative around \(a=0\) and positive around \(a=1\). There is necessarily only one inner root\(\ a^{*}\) for the same reason as in point 1). This unique inner root\(\ a^{*}\) must be unstable and divides the interval \(a\in (0,1)\) into two subintervals. The subinterval \((0,a^{*})\) is the basin of attraction of \( a=0\) and \((a^{*},1)\ \)of \(a=1\) which are locally stable.

The proof is complete. \(\square \)

First we show the proofs of Proposition 4 and 5 and then that of Propositions 2 and 3.

1.3 A.3 Proof of Proposition 4.

A closed form of g(a) is first obtained. The Eq. (1) with \(k=1\) can be rewritten as

Thus, the function g(a) can be written as \(g(a;n)=\left( 1-(1-a)^{n}\right) p+a^{n}(1-p)-a\)

Let \(\tilde{a}\) be the unique inner root of \(g(a;\bar{n})=0\), where \(n=\bar{n }\), and \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{1}{\bar{n}}<(1-p)\), see Proposition 1, i.e., \(a^{*}[\bar{n},k=1]=\tilde{a}\).

Let \(\check{a}\) be the unique inner root of \(g(a;\bar{n}+1)=0\), where \( n=\left( \bar{n}+1\right) \), and \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{1}{\bar{n}+1}<(1-p)\), i.e., \(a^{*}[\bar{n}+1,k=1]=\check{a}\). The proof of Proposition 1 shows, on the one hand, that \(g(0;\bar{n}+1)=g(1;\bar{n }+1)=0\). On the other hand, if \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{1}{\bar{n}+1}<(1-p)\), the function \(g(a;\bar{n}+1)>0\) if \(a\in (0,\check{a})\), and \(g(a;\bar{n}+1)<0\) if \(a\in (\check{a},1)\). Consequently, if the function \(g(a;\bar{n}+1)\) is negative in \(a=\tilde{a}\), i.e., \(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n}+1)<0\), then \(\tilde{a}> \check{a}\) because \(g(\check{a};\bar{n}+1)=0\), and the proof is complete. Thus, we only need to prove that \(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n}+1)<0\). Before doing this we characterized, the steady state \(\tilde{a}\). As the state \(\tilde{a}\) is a steady state with \(n=\bar{n}\),

\(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n})=\left( 1-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}}\right) p+\tilde{a}^{ \bar{n}}(1-p)-\tilde{a}=0\)

We now prove that \(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n}+1)<0\),

\(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n}+1)=\left( 1-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}+1}\right) p+\tilde{a} ^{\bar{n}+1}(1-p)-\tilde{a}<0\)

\(\Leftrightarrow p-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}+1}p+\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}+1}(1-p)- \tilde{a}(p+(1-p))<0\Longleftrightarrow \left( (1-\tilde{a})-(1-\tilde{a})^{ \bar{n}+1}\right) p<\left( \tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}+1}\right) (1-p)\)

\(\Leftrightarrow \frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}+1}}{(1-\tilde{a})-(1- \tilde{a})^{\bar{n}+1}}>\frac{p}{(1-p)}\)

[using (13)]

\(\Leftrightarrow \frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}+1}}{(1-\tilde{a})-(1- \tilde{a})^{\bar{n}+1}}>\frac{p}{(1-p)}=\frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}}}{ (1-\tilde{a})-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}}}\)

\(\Leftrightarrow \left( \frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}+1}}{(1-\tilde{a} )-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}+1}}>\frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}}}{(1-\tilde{a })-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}}}\right) \Leftrightarrow \left( \frac{\tilde{a} \left( 1-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}}\right) }{(1-\tilde{a})\left( 1-(1-\tilde{a})^{ \bar{n}}\right) }>\frac{\tilde{a}\left( 1-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}-1}\right) }{(1- \tilde{a})\left( 1-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}-1}\right) }\right) \)

\(\Leftrightarrow \left( \frac{1-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}}}{1-\tilde{a}^{\bar{n}-1}} >\frac{1-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}}}{1-(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}-1}}\right) \)

It is shown below that \(\frac{1-a^{\bar{n}}}{1-a^{\bar{n}-1}}\) is increasing in a and \(\frac{1-(1-a)^{\bar{n}}}{1-(1-a)^{\bar{n}-1}}\)is decreasing in a. In addition, the two terms are equal if \(a=\dfrac{1}{2}\). Consequently, if \(a>\dfrac{1}{2}\), then \(\frac{1-a^{\bar{n}}}{1-a^{\bar{n} -1}}>\frac{1-(1-a)^{\bar{n}}}{1-(1-a)^{\bar{n}-1}}\). Therefore, if \(\tilde{a} >\frac{1}{2}\), then \(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n}+1)<0\), and the proof is complete.

First, the derivative is \(\frac{d}{da}\left( \frac{1-a^{\bar{n}}}{1-a^{\bar{n }-1}}\right) =\frac{a^{\bar{n}}}{\left( a-a^{\bar{n}}\right) ^{2}}\left( \bar{n}-a\bar{n}+a^{\bar{n}}-1\right) \). The expression \(\left( \bar{n}-a \bar{n}+a^{\bar{n}}-1\right) \) is decreasing in a, takes the minimum value in \(a=1\), and \(\left. \left( \bar{n}-a\bar{n}+a^{\bar{n}}-1\right) \right| _{a=1}=0\), so \(\frac{d}{da}\left( \frac{1-a^{\bar{n}}}{1-a^{\bar{ n}-1}}\right) >0\).

Second, the derivative \(\frac{d}{da}\left( \frac{1-(1-a)^{\bar{n}}}{1-(1-a)^{ \bar{n}-1}}\right) =-\frac{\left( 1-a\right) ^{\bar{n}}}{\left( a+\left( 1-a\right) ^{\bar{n}}-1\right) ^{2}}\left( \left( 1-a\right) ^{\bar{n}}+a \bar{n}-1\right) \). The expression \(-\left( \left( 1-a\right) ^{\bar{n}}+a \bar{n}-1\right) \) is decreasing in a, takes the maximum value in \(a=0\), and \(\left. -\left( \left( 1-a\right) ^{\bar{n}}+a\bar{n}-1\right) \right| _{a=0}=0\), so \(\frac{d}{da}\left( \frac{1-(1-a)^{\bar{n}}}{ 1-(1-a)^{\bar{n}-1}}\right) <0\)

To conclude, it is shown that \(\tilde{a}>\frac{1}{2}\). The following claim proves this.

Claim 6

Let \(a^{*}[n,k=1]=\tilde{a}\), then \( \tilde{a}>\frac{1}{2}\)

Proof

With \(\tilde{a}\) the only steady state, the proof of Proposition shows that, if \(a\in (0,\tilde{a})\), then \(g(a)>0\) and, if \(a\in (\tilde{a},1)\), then \(g(a)<0\). In addition, by Lemma , \(g(\frac{1}{2})>0\), so \(\tilde{a}>\frac{1}{2}\).\(\quad \blacklozenge \)6\(\square \)

1.4 A.4 Proof of Proposition 5.

By Proposition 1 , if \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{1}{n }<(1-p)\) then there is only one inner steady state \(a^{*}[n,k=1]\), which is globally stable. Let \(a^{*}[n,k=1]=\tilde{a}\), and consequently \(g( \tilde{a})=0\).

In the proof of Proposition 4 , it is shown that the expression \(g(\tilde{a})=0\) is equivalent to (13),

\(g(\tilde{a})=0\Longleftrightarrow \left( \frac{p}{1-p}=\frac{\tilde{a}- \tilde{a}^{n}}{(1-\tilde{a})-(1-\tilde{a})^{n}}\right) \)

On the one hand, the expression \(\frac{p}{1-p}\) is increasing in p. On the other hand, the expression \(\frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{n}}{(1-\tilde{a})-(1- \tilde{a})^{n}}\) is increasing in \(\tilde{a}\). Therefore, if p increases, then \(\frac{p}{1-p}\) increases, which finally means that \(\tilde{a}\) must increase.Footnote 27 To end the proof, we only need to prove that:

\(\frac{d}{d\tilde{a}}\left( \frac{\tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{n}}{(1-\tilde{a})-(1- \tilde{a})^{n}}\right) =\frac{\left( 1-\tilde{a}-(1-\tilde{a})^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }\tilde{a}^{n-1}\right) +\left( \tilde{a}-\tilde{a} ^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }(1-\tilde{a})^{n-1}\right) }{\left( 1-\tilde{a} -(1-\tilde{a})\right) ^{2}}>0\)

\(\iff \left( 1-\tilde{a}-(1-\tilde{a})^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }\tilde{a} ^{n-1}\right) +\left( \tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }(1- \tilde{a})^{n-1}\right) >0\)

the previous expression is decreasing in \(\tilde{a}\) for \(\tilde{a}>\frac{1}{ 2}\) and increasing for \(\tilde{a}<\frac{1}{2}\). Notice that,

\(\frac{d}{d\tilde{a}}(\left( 1-\tilde{a}-(1-\tilde{a})^{n}\right) \left( 1-n \text { }\tilde{a}^{n-1}\right) +\left( \tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }(1-\tilde{a})^{n-1}\right) )=\)

\(\frac{((1-\tilde{a})^{n}\tilde{a}^{3} +\tilde{a}^{n}(1-\tilde{a})^{n}+\tilde{ a}^{n}((-1+\tilde{a})^{3}-2(1-\tilde{a}) ^{n}\tilde{a}))(n-1)n)}{(-1+\tilde{a} )^{2}\tilde{a}^{2}}\gtrless 0\)

\(\iff ((1-\tilde{a})^{n}\tilde{a}^{3}+ \tilde{a}^{n}(1-\tilde{a})^{n}+\tilde{a }^{n}((-1+\tilde{a})^{3}-2(1-\tilde{a})^{n}\tilde{a}))\gtrless 0\)

\(\iff ((1-\tilde{a})^{n}\tilde{a}^{3}-\tilde{a}^{n}(1-\tilde{a})^{3}+\tilde{a }^{n}(1-\tilde{a})^{n}-\tilde{a}^{n}(1-\tilde{a})^{n}2\tilde{a}\gtrless 0\)

\(\iff \tilde{a}^{3}(1-\tilde{a})^{3}((1-\tilde{a})^{n-3}-\tilde{a}^{n-3})+ \tilde{a}^{n}(1-\tilde{a})^{n}(1-2\tilde{a})\gtrless 0\)

Clearly,with \(\tilde{a}>\frac{1}{2}\) the expression is negative, and it is positive if \(\tilde{a}<\frac{1}{2}\).

Consequently, as \(\left( 1-\tilde{a}-(1-\tilde{a})^{n}\right) \left( 1-n \text { }\tilde{a}^{n-1}\right) +\left( \tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }(1-\tilde{a})^{n-1}\right) \) is zero in \(\tilde{a}=1\), it will be positive for all \(\tilde{a}\in (\frac{1}{2},1)\). In addition, since \(\left( 1-\tilde{a}-(1-\tilde{a})^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }\tilde{a} ^{n-1}\right) +\left( \tilde{a}-\tilde{a}^{n}\right) \left( 1-n\text { }(1- \tilde{a})^{n-1}\right) \) is zero in \(\tilde{a}=0\), it will be positive for all \(\tilde{a}\in (0,\frac{1}{2})\). \(\square \)

1.5 A.5 Proof of Proposition 2.

The proof is analogous to the proof of Proposition 4 and some of the identical steps are omitted.

The claim above gives a closed form of the function g(a) with \(k=n-1\).

Claim 7

With \(k=n-1\), the function \(g(a)=\frac{1}{n-1}\left( an-a^{n}p-(1-p)+(1-a)^{n}\right. \left. (1-p)\right) -a\)

Proof

From Eq. (1) with \(k=n-1\):

(using Claim 2)

Thus, \(g(a)=f(a)-a=\frac{1}{n-1}\left( an-a^{n}p-(1-p)+(1-a)^{n}(1-p)\right) -a\)

\(=\frac{1}{n-1}\left( an-a^{n}p-(1-p)+(1-a)^{n}(1-p)\right) -a \blacklozenge \)

Let \(\tilde{a}\) be the unique inner root of \(g(a;\bar{n})=0\), where \(n=\bar{n }\), and \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{\bar{n}-1}{\bar{n}}>p\). See Proposition 1.

Let \(\check{a}\) be the unique inner root of \(g(a;\bar{n}+1)=0\), where \(n= \bar{n}+1\), and \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{(\bar{n}+1)-1}{\bar{n}+1}=\frac{\bar{n}}{ \bar{n}+1}>p\). The proof of Proposition 1 shows, on the one hand, that \(g(0;\bar{n}+1)=g(1;\bar{n}+1)=0\). On the other hand, with \(\frac{k}{n}=\frac{\bar{n}}{\bar{n}+1}>p\), the function \(g(a;\bar{n} +1)<0\) if \(a\in (0,\check{a})\), and \(g(a;\bar{n}+1)>0\) if \(a\in (\check{a} ,1) \). Consequently, if the function \(g(a;\bar{n}+1)\) is negative in \(a= \tilde{a} \) then \(\tilde{a}<\check{a}\), because \(g(\check{a};\bar{n}+1)=0\), and the proof is complete. Thus, we only need to prove that \(g(\tilde{a}; \bar{n}+1)<0 \). Before we do so, we characterized the steady state \(\tilde{a} \) is . As the state \(\tilde{a}\) is a steady state with \(n=\bar{n}\),

\(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n})=\frac{1}{\bar{n}-1}\left( \tilde{a}\bar{n}-\tilde{a}^{ \bar{n}}p-(1-p) +(1-\tilde{a})^{\bar{n}}(1-p)\right) -\tilde{a}=0\)

We now prove that \(g(\tilde{a};\bar{n}+1)<0\),

[using Eq. (14)]

The rest of the proof is analogous to that of Proposition 4 and is omitted. \(\square \)

1.6 A.6 Proof of Proposition 3

The proof is analogous to the proof of Proposition 3 and is omitted (we use expression 14 instead of 13). \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Martínez, J.A. A simple dynamic contest with a parameterized strength of competition. SERIEs 9, 305–332 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-018-0180-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13209-018-0180-6