Abstract

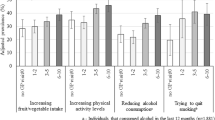

Patient-centered health risk assessments (HRAs) that screen for unhealthy behaviors, prioritize concerns, and provide feedback may improve counseling, goal setting, and health. To evaluate the effectiveness of routinely administering a patient-centered HRA, My Own Health Report, for diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol, drug use, stress, depression, anxiety, and sleep, 18 primary care practices were randomized to ask patients to complete My Own Health Report (MOHR) before an office visit (intervention) or continue usual care (control). Intervention practice patients were more likely than control practice patients to be asked about each of eight risks (range of differences 5.3–15.8 %, p < 0.001), set goals for six risks (range of differences 3.8–16.6 %, p < 0.01), and improve five risks (range of differences 5.4–13.6 %, p < 0.01). Compared to controls, intervention patients felt clinicians cared more for them and showed more interest in their concerns. Patient-centered health risk assessments improve screening and goal setting.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01825746

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004; 291(10): 1238-1245.

Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, et al. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet. 2014; 384(9937): 45-52.

Woolf SH, Aron LY, National Academies (U.S.). Panel on Understanding Cross-National Health Differences Among High-Income Countries, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. U.S. Health in International Perspective : Shorter Lives, Poorer Health.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. 2012; http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx. Accessed Jan. 2013.

Phillips SM, Glasgow RE, Bello G, et al. Frequency and prioritization of patient health risks from a structured health risk assessment. Ann Fam Med. 2014; 12(6): 505-513.

DeGruy FV, Etz RS. Attending to the whole person in the patient-centered medical home: the case for incorporating mental healthcare, substance abuse care, and health behavior change. Fam Syst Health: J Collaborative Fam Healthcare. 2010; 28(4): 298-307.

Goldstein MG, Whitlock EP, DePue J. Multiple behavioral risk factor interventions in primary care. Summary of research evidence. Am J Prev Med. 2004; 27(2 Suppl): 61-79.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). Primary Care and Public Health. Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2012.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Preventive Services. 2014; http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/. Accessed Jan. 2015

Krist AH, Baumann LJ, Holtrop JS, et al. Evaluating feasible and referable behavioral counseling interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49(3 Suppl 2): S138-149.

Goetzel RZ, Staley P, Ogden L, Stange P, Fox J, Spangler J, Tabrizi M, Beckowski M, Kowlessar N, Glasgow RE, Taylor MV. A framework for patient-centered health risk assessments - providing health promotion and disease prevention services to Medicare beneficiaries. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centeres for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011; http://www.cdc.gov/policy/opth/hra/. Accessed Feb. 2014.

Goodyear-Smith F, Warren J, Bojic M, et al. eCHAT for lifestyle and mental health screening in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2013; 11(5): 460-466.

The patient protection and affordable care act. Public Law 111–1148. 2nd Session ed 2010.

Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns. 2012; 87(1): 32-42.

Strecher VJ, Seijts GH, Kok GJ, et al. Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1995; 22(2): 190-200.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Smith SP. Using goal setting as a strategy for dietary behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001; 101(5): 562-566.

Shilts MK, Horowitz M, Townsend MS. Goal setting as a strategy for dietary and physical activity behavior change: a review of the literature. Am J Health Promot. 2004; 19(2): 81-93.

Shekelle PG, Tucker JS, Maglione M, et al. Health risk appraisals and medicare. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 2003.

Guide to Community Preventive Services. 2015; http://www.thecommunityguide.org/. Accessed Feb. 2015.

Halpin HA, McMenamin SB, Schmittdiel J, et al. The routine use of health risk appraisals: results from a national study of physician organizations. Am J Health Promot. 2005; 20(1): 34-38.

Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005; 83(3): 457-502.

Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA, et al. Direct observation of rates of preventive service delivery in community family practice. Prev Med. 2000; 31(2 Pt 1): 167-176.

Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, et al. Illuminating the ‘black box’. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1998; 46(5): 377-389.

Elwy AR, Horton NJ, Saitz R. Physicians’ attitudes toward unhealthy alcohol use and self-efficacy for screening and counseling as predictors of their counseling and primary care patients’ drinking outcomes. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013; 8: 17.

Nelson KE, Hersh AL, Nkoy FL, et al. Primary care physician smoking screening and counseling for patients with chronic disease. Prev Med. 2014; 71C: 77-82.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for and management of obesity in adults. 2012; http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsobes.htm. Accessed Jan. 2013.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents. 2010; http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspschobes.htm. Accessed Mar, 2013.

Krist AH, Glenn BA, Glasgow RE, et al. Designing a valid randomized pragmatic primary care implementation trial: the my own health report (MOHR) project. Implement Sci: IS. 2013; 8: 73.

Rodriguez HP, Glenn BA, Olmos TT, et al. Real-world implementation and outcomes of health behavior and mental health assessment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014; 27(3): 356-366.

Krist AH, Phillips SM, Sabo RT, et al. Adoption, reach, implementation, and maintenance of a behavioral and mental health assessment in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014; 12(6): 525-533.

My Own Heath Report. www.MyOwnHealthReport.org. Accessed Jan. 2014.

Estabrooks PA, Boyle M, Emmons KM, et al. Harmonized patient-reported data elements in the electronic health record: supporting meaningful use by primary care action on health behaviors and key psychosocial factors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012; 19(4): 575-582.

Glasgow RE, Kaplan RM, Ockene JK, et al. Patient-reported measures of psychosocial issues and health behavior should be added to electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012; 31(3): 497-504.

Croteau J, Ryan D. Acheiving your SMART health goals. BeWell@Stanford. 2013; http://bewell.stanford.edu/smart-goals. Accessed Jan. 2013.

O’Neil j. SMART Goals, SMART Schools. Educational Leadership. 2000:46–50.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS Clinician & Group Surveys. http://cahps.ahrq.gov/clinician_group/. Accessed Nov. 2014.

Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2nd ed. John Wiley Company: Hoboken; 1999.

Lu N, Samuels ME, Wilson R. Socioeconomic differences in health: how much do health behaviors and health insurance coverage account for? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004; 15(4): 618-630.

Krist AH, Shenson D, Woolf SH, et al. Clinical and community delivery systems for preventive care: an integration framework. Am J Prev Med. 2013; 45(4): 508-516.

Glasgow RE, Kessler RS, Ory MG, et al. Conducting rapid, relevant research: lessons learned from the My Own Health Report project. Am J Prev Med. 2014; 47(2): 212-219.

Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. 2009; http://www.pcpcc.net/. Accessed Sept. 2014.

McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, et al. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010; 29(5): 982-990.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the MOHR project was provided by the National Cancer Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (CTSA Grant Number ULTR00058). The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders.

We would like to thank the research teams for their valuable efforts including Melissa Hayes, Steve Mitchell, Mark Greenawald, Mark Kelly, Rodger Kessler, Jill Arklind, Joseph Carroll, Christine Nelson, John Heintzman, Maria Fernandez, Kayla Fair, Julie Ribardo, Dylan Roby, Jennifer Leeman, and Alexis Moore.

Most of all, we would like to thank our practices for their partnership, insights, and hard work: Vienna Primary and Preventive Medicine, Little Falls Family Practice, Charles City Regional Health Services, Chester Family MedCare, Carilion Family Medicine—Roanoke Salem, Carilion Family Medicine—Southeast, Berlin Family Health, Milton Family Practice, Humbolt Open Door Clinic, McKinleyville Community Health Center, St. Johns’ Well Child and Family Center, Spring Branch Community Health Center—Pitner Clinic, Spring Branch Community Health Center—Hillendahl Clinic, HealthPoint Community Health Centers—Navasota, HealthPoint Community Health Centers—Hearne, Murfeesboro Clinic, and Snow Hill Clinic

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have adhered to ethical principles throughout this research study including writing and submitting this manuscript. Specifically, we adhered to the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines, seven institutional IRB protocols, and appropriate informed consent processes for research participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Implications

Practice

Administering a patient-centered health risk assessment in primary care will identify a significant number of unhealthy behaviors and mental health needs allowing patients and clinicians to better set goals that will improve health.

Policy

Better integration of primary care with mental health and health behavior counselors is needed to address the modifiable risks that will be identified as health risk assessments are more commonly used in primary care.

Research

A greater understanding about how to routinely support the use of health risk assessments in primary care as well as how to deliver intensive counseling to patients ready to make changes is needed.

About this article

Cite this article

Krist, A.H., Glasgow, R.E., Heurtin-Roberts, S. et al. The impact of behavioral and mental health risk assessments on goal setting in primary care. Behav. Med. Pract. Policy Res. 6, 212–219 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0384-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-015-0384-2