Abstract

Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD) of the lower limbs is a common problem. It is more prevalent in women than in men and has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL) and on the healthcare system. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of sulodexide in adult patients with CVD of the lower limbs and its effect on patients’ QoL.

Methods

Patients with CVD were treated with sulodexide [250 LSU (lipasemic units) twice daily] for 3 months in a setting of real-life clinical practice. The endpoints of this observational non-comparative, open-label prospective study were the clinical efficacy of sulodexide (evaluated by scoring objective and subjective symptoms with a Likert-type scale) and the impact of sulodexide therapy on patients’ QoL [assessed using the chronic venous insufficiency quality of life questionnaire (CIVIQ)].

Results

The study included 450 patients (mean age 46.9 ± 10.5 years, range 17–78 years). A greater percentage of patients were female (65.4%). Three months of treatment with sulodexide significantly improved all objective and subjective symptoms (p < 0.0001). Overall, patients reported a significant improvement in all QoL scores (p < 0.0001). Adverse events were spontaneously reported by two patients (one case of epigastric pain and one of gastric pain with vomiting).

Conclusion

Oral sulodexide significantly improves both objective and subjective symptoms, as well as functional and psychological aspects of QoL in patients with CVD.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study. Sponsorship for article processing charges and open access fees was provided by Alfa Wassermann.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD) of the lower limbs is a condition of the venous system in which venous hypertension may cause various symptoms and signs that may include (in the order of severity, greatest to least): pain, swelling, oedema, skin changes, subcutaneous tissue fibrosis and ulcerations [1]. In CVD, normal venous pressure is increased and the return of blood is impaired via several mechanisms, such as structural or functional alteration of the vein walls, valvular incompetence of deep, superficial or perforator veins, venous obstruction or a combination of these [1]. Occurring more frequently in women than in men, CVD is a common medical condition that has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL) and the healthcare system [1, 2].

Inflammatory processes have demonstrated involvement in structural remodelling of venous valves and the vein wall, leading to valvular incompetence and the development of varicose veins [3]. Various factors can lead to inflammation of the vessel wall. The venous system of the lower limbs undergoes frequent postural pressure changes; however, prolonged periods of sitting or standing can lead to venous stasis, which causes vein distension and valve distortion. Leakage of blood through these damaged valves leads to flow reversal, which in turn initiates endothelial and leukocyte activation [4]. These inflammatory stresses, when repeated over time, eventually lead to chronic recurrent injury to the venous wall, perpetuating inflammation at the vein level [4].

A second significant pro-inflammatory factor is altered shear stress. Normal shear stress, or steady laminar blood flow, promotes the release of factors that reduce inflammation and the formation of reactive free radicals [1]. In contrast, low or zero shear stress (disturbed or turbulent flow and especially reversal of the direction of blood flow) induces venous inflammation and thrombosis [1]. The endothelium, particularly the endothelial glycocalyx (the carbohydrate-rich layer of proteoglycans and glycoprotein lining the vascular endothelium) [5], is responsible for translating biomechanical forces into protective biochemical signals (e.g. the production of the vasodilator nitric oxide) [1, 5]. Almost all of the mechanical stress caused by luminal flow is transferred to the glycocalyx, thus virtually eliminating the shear stress at the surface of the venular endothelium [1]. The glycocalyx also inhibits leukocyte adhesion by masking cell adhesion molecules [1]. However, the glycocalyx may be damaged by inflammation which may alter responses to shear stress and result in further leukocyte adhesion.

Irrespective of the trigger for inflammatory events in venous valves and walls, various inflammatory mediators and growth factors are released. These include chemokines, cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, transforming growth factor beta, fibroblast growth factor beta and vascular endothelial growth factor [4, 6]. Together, these inflammatory mediators and growth factors perpetuate inflammation, leading to structural remodelling of vein walls and valves, venous dilation, varicose veins and ulceration [6].

Early treatment for the prevention of venous hypertension and the inhibition of the inflammatory cascade, especially leukocyte-endothelium interactions, could alleviate symptoms of CVD and slow or prevent disease progression to chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) and ulcers [1, 3]. The current recommended first-line treatment of CVD involves conservative measures, such as lifestyle modifications and compression therapy, with frequent addition of veno-active drugs for the treatment of CVD-related symptoms [4, 7]. Interventional therapy is only considered for the treatment of specific signs and symptoms or if conservative therapy fails [7].

Sulodexide is a specific glycosaminoglycan (GAG), composed of a fast-moving heparin fraction (80%) with affinity for antithrombin III, and a dermatan sulphate fraction (20%) with affinity for heparin cofactor II [8]. Sulodexide exerts a strong anti-thrombotic activity by simultaneously potentiating the antiprotease activities of both antithrombin III and heparin cofactor II [8]. Sulodexide also has a profibrinolytic effect (via activation of tissue plasminogen activator and inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor), an antiproliferative effect on smooth muscle cells and antilipaemic and antiatherosclerotic effects [8].

Several clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of sulodexide in the treatment or prevention of vascular diseases associated with increased thrombotic risk, such as peripheral arterial occlusive diseases [9, 10], post-myocardial infarction [11], recurrent deep vein thrombosis [12, 13] and post-thrombotic syndrome [14, 15].

More recently, the antiplatelet [16] and anti-inflammatory [17] activities of sulodexide have been highlighted, together with its significant protective effect on the glycocalyx layer [18]. This suggests that the administration of sulodexide in patients with CVD may interfere with the pathogenesis of the disease, not only when it is linked to previous deep vein thrombosis (secondary venous disease or post-thrombotic syndrome), but also in case of primary venous disease. In fact, favourable effects on clinical signs and symptoms of CVD have been documented following the administration of sulodexide regardless of the underlying aetiology of the venous disease [19, 20]. However, no data are currently available in peer review publications regarding the effects of sulodexide on patients’ QoL using validated tests.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of oral sulodexide on both clinical symptoms and QoL in adult patients with CVD of the lower limbs.

Methods

This observational non-comparative, open-label prospective study was conducted at 50 centres in Tunisia during 2008 (see the complete list at the end of the article). Adult patients with CVD of the lower limbs were included. Exclusion criteria included: age >70 years; presence of arteriopathies of the lower limbs; rheumatic, musculotendinous, neurologic, metabolic or haemorrhagic diseases, including haemorrhagic diathesis; concomitant anticoagulant treatment; hypersensitivity to sulodexide or other GAGs. Pregnant or breastfeeding women were also excluded.

Patients were evaluated at baseline (enrolment visit, T0) and after 3 months (end of study visit, T3) of oral treatment with sulodexide capsules (Vessel®, Alfa Wassermann, Alanno (PE), Italy) 250 LSU (lipasemic units, approximately equivalent to 25 mg) twice daily. Demographic data (sex, age, origin area) were collected during the enrolment visit. At both visits, the investigator evaluated subjective symptoms (heaviness, pain, cramps and paresthesias) and objective symptoms (erythema, skin temperature and induration) of CVD in the lower limbs using a 4-point Likert-type scale (0-absent, 1-moderate, 2-severe and 3-very severe).

In addition, the chronic venous insufficiency quality of life (CIVIQ) questionnaire was used to gauge patients’ QoL based on self-evaluation of their health status over the last 4 weeks using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1-best possible condition, 5-worst possible condition). This questionnaire was developed by Prof. Launois with an educational grant from Servier [21, 22]. Assessments were performed at baseline and after 3 months of therapy with sulodexide and included the patient’s assessment of severity of pain, functional limitation (in general and in individual activities), sleep and several psychological aspects related to CVD.

The endpoints of the study were the clinical effectiveness of sulodexide treatment and its impact on patients’ QoL. Tolerability of sulodexide was not formally analysed as patients were not systematically asked about the occurrence of adverse events during the study period, nor at the final visit.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarised using standard descriptive methods. Symptom and QoL scores were analysed at both T0 and T3, when available. Mean compound scores were calculated for all symptoms [functional QoL (including pain-related symptoms), and mental QoL (including sleep-related symptoms)], providing that more than half of the questionnaire items were answered at both T0 and T3. Comparisons between visits were carried out using Wilcoxon’s test for paired samples (signed rank test). Two-sided p < 0.01 were considered as statistically significant. T3/T0 mean compound score ratios were analysed using mixed models, with age (≤45 or >45 years) and gender as fixed effects, and centre as random effect. Statistical analysis was carried out using the SAS® System version 8.2.

Results

Patients

A total of 450 patients were included in the study, mostly from urban (92.9%) rather than rural (7.1%) areas. The mean age (±SD) of patients was 46.9 ± 10.5 years (range 17–78 years); 53.0% were >45 years and three patients were >70 years (older than the upper limit of 70 years specified for the study). A higher proportion of patients were females (65.4%). A total of 436 patients (96.9%) completed the study by attending the final visit at 3 months after enrolment. Reasons for failing to complete the study included withdrawal from the study because of adverse events (specifically, epigastric pain and gastric pain with vomiting; 2 patients) and loss to follow-up for unknown reasons (12 patients).

Efficacy

Symptoms

The number and percentage of patients with each score for subjective and objective symptoms at both T0 and T3 are reported in Table 1. The number of patients with data available from both visits varied from 430 patients for leg heaviness to 410 patients for erythema.

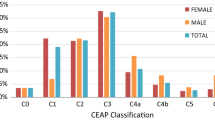

Three months of treatment with sulodexide significantly improved all subjective and objective symptoms: the median improvement for all symptoms was 1 unit on the Likert scale, meaning median values shifted from severe to moderate for leg heaviness and pain and from moderate to absent for all other symptoms. Mean symptom scores at baseline and at the final visit are shown in Fig. 1. All improvements were statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Mean compound scores at T0 and T3 and their percent reduction at T3 compared with T0, calculated for each patient, are summarised in Table 2. All changes were statistically significant (p < 0.0001) in each of the four subgroups, in which patients were stratified by age and gender. Centre-adjusted differences between age and gender subgroups in T3/T0 score ratios were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Patients attending for observation in our centres presented mostly with subjective symptoms of severe or very severe intensity (heaviness, 54.9% and 31.6%, respectively; pain, 48.8% and 29.0%, respectively) or of severe to moderate intensity (cramps, 36.0% and 36.0%, respectively; paresthesias, 33.3% and 33.3%, respectively). Up to slightly more than one-third of patients showed no objective symptoms (erythema, 36.6%; skin temperature, 25.5%; induration, 37.1%) at baseline; when present, these symptoms were mostly reported as moderate or severe (Table 1). Treatment with sulodexide reduced the intensity of each subjective and objective symptom, an effect which was directly proportional to its initial intensity (Fig. 1).

Quality of Life

All the items of the CIVIQ questionnaire were evaluated at T0 and T3. The number of patients with data available from both visits varied across the items, from 426 patients for “Climbing stairs” (F2) to 404 patients for “Sporting activities, making physically strenuous efforts” (F8). After 3 months of treatment, the median improvement for all items was 1 unit on the Likert-type scale, except for the item “Standing for a long time” (F1), which showed a median improvement of 2 units. Mean scores at T0 and T3 are shown in Figs. 2 and 3; all improvements were highly significant (p < 0.0001) and similar for questions related to pain and functional activities (mean improvement of 44%) and to sleep and mental symptoms (mean improvement of 40%) (Table 2). Changes were statistically significant in each of the four subgroups, in which patients were stratified by age and gender (p < 0.0001). No statistically significant differences were observed between the subgroups (p > 0.05).

Quality of life (pain-related and functional activities) in patients receiving sulodexide for chronic venous disease. Mean chronic venous insufficiency quality of life (CIVIQ) questionnaire scores as assessed by patients at baseline and after 3 months of treatment with sulodexide. Lower scores in the CIVIQ mean better quality of life

Quality of life (sleep-related and mental symptoms) in patients receiving sulodexide for chronic venous disease. Mean chronic venous insufficiency quality of life (CIVIQ) questionnaire scores as assessed by patients at baseline and after 3 months of treatment with sulodexide. Lower scores in the CIVIQ mean better quality of life

Safety

Adverse events were spontaneously reported by two patients (epigastric pain and gastric pain with vomiting). However, other patients were not systematically asked about adverse events so no other data are available.

Discussion

In our study, administration of oral sulodexide for 3 months to 450 adult patients with CVD in a setting of real-life clinical practice led to statistically significant improvements in the subjective (heaviness, pain, cramps and paresthesias) and objective (erythema, skin temperature and induration) symptoms as well as patients’ QoL compared with baseline.

These results are consistent with those of previous studies reporting the effectiveness of sulodexide in the treatment of CVD. A double-blind, double-dummy, randomised study by Saviano and co-workers [19] compared the efficacy, dose–effect relationship and tolerability of sulodexide given orally as capsules or enteric coated tablets for 60 consecutive days in 476 patients with CVI. The results of the study showed a dose-related and statistically significant decrease in the number and intensity of the subjective and objective symptoms such as pain, limb heaviness, paresthesias, nocturnal cramps, foot and leg oedema, skin pigmentation, hypodermitis, lymphangitis and stasis ulcer with sulodexide treatment. With the exception of hypodermitis, lymphangitis and stasis ulcer, which were present in a small number of patients and with a limited intensity at baseline, the reduction in the intensity of symptoms compared with baseline was first observed at 30 days (p < 0.025) in all dose groups. Another randomised, double blind, multicentre, placebo controlled study evaluated the effect of sulodexide in the treatment of venous leg ulcers (>2 cm in diameter), with complete healing of ulcers at 2 months as the primary endpoint [20]. Venous leg ulcers are the most severe manifestation of CVD and the healing of a venous ulcer represents an important, objective and ‘hard’ endpoint in defining the role of medications for the treatment of CVD. The trial involved a total of 230 patients, randomised to sulodexide (n = 120) or placebo (n = 110) in addition to local treatment, including wound care and compression bandaging. In the intent-to-treat population the primary endpoint was reached in 35.0% of patients receiving sulodexide and 20.9% of placebo recipients (p = 0.018). At 3 months the difference between the sulodexide and placebo groups increased further, with healing rates of 52.5% in patients receiving sulodexide and 32.7% in those receiving placebo (p = 0.004). The reduction in ulcer surface area with time was significant for the sulodexide group (p = 0.004) and the treatment was well tolerated, with no differences in adverse events reported between the sulodexide and placebo group.

QoL reflects the patients’ perception of their “well-being” at any time and, therefore, it is an important health outcome. Illness has a profound effect on a patient’s QoL and questionnaires, both generic and specific for venous disease, show that QoL is adversely affected by venous disease and that any reduction in the severity of disease, for example after treatment, is reflected in the QoL [7]. Our data show that 3 months of treatment with sulodexide significantly improved the QoL of patients with CVD in pain-related and functional items as well as in sleep and mental items.

Since our study is the first evaluating the effects of sulodexide in CVD patients using a validated questionnaire for the measurement of QoL, comparisons can only be made with studies carried out with other phlebotropic drugs. In a large prospective international, multicentre study, that was non-comparative as far as treatment is concerned, QoL was evaluated using the CIVIQ questionnaire in more than 3600 patients with CVI. Treatment with 1000 mg of micronized purified flavonoid fraction administered daily for 6 months resulted in a significant improvement of QoL, which was greater after 2 months of treatment, but with further improvements after 4 and 6 months [23]. Among other large trials using the CIVIQ questionnaire as a quantitative instrument to assess health-related QoL changes in patients with CVD, a very short-term (7 days) study by Guex and colleagues reported statistically significant improvements in QoL in 399 symptomatic female patients treated with an unspecified phlebotropic drug [24]. More recently, an observational, single arm, international, multicentre, prospective trial in 1953 patients with CVD showed that the administration of a combination of Ruscus aculeatus (150 mg), hesperin methyl chalcone (150 mg) and ascorbic acid (100 mg) twice daily resulted in significant improvements in QoL after 12 weeks of treatment [25].

To our knowledge, only a few placebo-controlled studies have evaluated the effects of treatment with veno-active drugs on the QoL of patients with CVD. In a recent trial, Belczak and colleagues [26] studied the effects of different veno-active drugs on limb volume reduction, tibiotarsal range of motion, and QoL in 136 patients with CVD; a 30-day treatment with diosmin plus hesperidin (450 and 50 mg), or aminaphtone (75 mg), or coumarin plus troxerutin (15 and 90 mg) or placebo every 12 h showed a significant improvement in QoL (a) versus baseline in the aminaphtone and diosmin plus hesperidin treatment groups and (b) versus placebo only in the aminaphtone group (p = 0.007), while in the diosmin plus hesperidine group the improvement tended toward significance (p = 0.055). Another randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial including 509 patients with CVD suggested that the effects of calcium dobesilate on QoL may be dependent on the duration of treatment: there was no significant difference in QoL, measured by the CIVIQ questionnaire, between calcium dobesilate (500 mg twice a day) and placebo (p = 0.07) at 3 months (the primary endpoint), but a significant difference in favour of calcium dobesilate (p = 0.02) was observed after 12 months of treatment (a secondary endpoint) [21].

In our study, treatment with sulodexide showed significant improvement from baseline of both QoL and clinical symptoms after 3 months of treatment in an adequate number of patients. However, no control group was used, which is a significant limitation of the study, and caution should be exercised in the evaluation of the results as improvements may be in part due to a greater care to which the patients included in clinical trials are subjected. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the changes in symptoms and signs reported in similar randomised, controlled studies moved in the same favourable direction. In our study the response to sulodexide treatment was assessed by evaluating some important subjective and objective symptoms of CVD using the 4-point Likert-type scale. However, no widely accepted classification of CVD, such as the CEAP classification [27], was referred to, which is another limitation of the study. Also, the lack of a systematic active collection of tolerability data was a clear limitation of the study. Treatment emergent adverse events were only recorded if spontaneously reported by the study patients. However, the clinical experience with sulodexide in patients with CVD shows that the drug is generally well tolerated [14, 15, 19, 20, 28–35].

Conclusions

In spite of the limitations, our data on more than 400 patients provide additional support for the use of sulodexide in patients with CVD. In particular, after 3 months of treatment with sulodexide, we documented a significant increase in QoL in comparison with the pre-treatment conditions, and observed significant improvement in clinical signs and symptoms as already shown in previous randomised controlled studies in patients with CVD. Improvement of signs, symptoms and QoL was similar irrespective of age and gender. Sulodexide is already included among the few drugs recommended for the treatment of this indication in authoritative guidelines; however, further randomised controlled studies in specific patient populations would be welcomed to better define its therapeutic role.

References

Bergan J, Schmid-Schönbein G, Smith P, Nicolaides A, Boisseau M, Eklof B. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(5):488–98.

Lozano Sanchez FS, Sanchez Nevarez I, Gonzalez-Porras JR, Marinello Roura J, Escudero Rodriguez JR, Diaz Sanchez S, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: influence of the socio-demographical and clinical factors. Int Angiol. 2013;32(4):433–41.

Nicolaides A. Chronic venous disease and the leukocyte-endothelium interaction: from symptoms to ulceration. Angiology. 2005;56(Suppl 1):S11–9.

Perrin M, Ramelet A. Pharmacological treatment of primary chronic venous disease: rationale, results and unanswered questions. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(1):117–25.

Reitsma S, Slaaf D, Vink H, van Zandvoort M, oude Egbrink M. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454(3):345–59.

Raffetto J, Mannello F. Pathophysiology of chronic venous disease. Int Angiol. 2014;33(3):212–21.

Nicolaides A, Allegra C, Bergan J, Bradbury A, Cairols M, Carpentier P, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs: guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2008;27(1):1–59.

Coccheri S, Mannello F. Development and use of sulodexide in vascular diseases: implications for treatment. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;8:49–65.

Gaddi A, Galetti C, Illuminati B, Nascetti S. Meta-analysis of some results of clinical trials on sulodexide therapy in peripheral occlusive arterial disease. J Int Med Res. 1996;24(5):389–406.

Coccheri S, Scondotto G, Agnelli G, Palazzini E, Zamboni V. Sulodexide in the treatment of intermittent claudication. Results of a randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled study. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(13):1057–65.

Condorelli M, Chiariello M, Dagianti A, Penco M, Dalla Volta S, Pengo V, et al. IPO-V2: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, comparative clinical investigation of the effects of sulodexide in preventing cardiovascular accidents in the first year after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23(1):27–34.

Errichi B, Cesarone M, Belcaro G, Marinucci R, Ricci A, Ippolito A, et al. Prevention of recurrent deep venous thrombosis with sulodexide: the SanVal registry. Angiology. 2004;55(3):243–9.

Cirujeda J, Granado P. A study on the safety, efficacy, and efficiency of sulodexide compared with acenocoumarol in secondary prophylaxis in patients with deep venous thrombosis. Angiology. 2006;57(1):53–64.

Cospite M, Milio G, Ferrara F, Cospite V, Palazzini E. Haemodynamic effects of sulodexide in post-thrombophlebitic syndromes. Acta Ther. 1992;18:149–61.

Luzzi R, Belcaro G, Dugall M, Hu S, Arpaia G, Ledda A, et al. The efficacy of sulodexide in the prevention of postthrombotic syndrome. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;20(6):594–9.

Adiguzel C, Iqbal O, Hoppensteadt D, Jeske W, Cunanan J, Litinas E, et al. Comparative anticoagulant and platelet modulatory effects of enoxaparin and sulodexide. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009;15(5):501–11.

Mannello F, Ligi D, Raffetto J. Glycosaminoglycan sulodexide modulates inflammatory pathways in chronic venous disease. Int Angiol. 2014;33(3):236–42.

Broekhuizen L, Lemkes B, Mooij H, Meuwese M, Verberne H, Holleman F, et al. Effect of sulodexide on endothelial glycocalyx and vascular permeability in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2010;53(12):2646–55.

Saviano M, Maleti O, Liguori L. Double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, multi-centre clinical assessment of the efficacy, tolerability and dose-effect relationship of sulodexide in chronic venous insufficiency. Curr Med Res Opin. 1993;13(2):96–108.

Coccheri S, Scondotto G, Agnelli G, Aloisi D, Palazzini E, Zamboni V. Randomised, double blind, multicentre, placebo controlled study of sulodexide in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87(6):947–52.

Martínez-Zapata M, Moreno R, Gich I, Urrútia G, Bonfill X. A randomized, double-blind multicentre clinical trial comparing the efficacy of calcium dobesilate with placebo in the treatment of chronic venous disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35(3):358–65.

Launois R, Reboul-Marty J, Henry B. Construction and validation of a quality of life questionnaire in chronic lower limb venous insufficiency (CIVIQ). Qual Life Res. 1996;5(6):539–54.

Jantet G. Chronic venous insufficiency: worldwide results of the RELIEF study. Angiology. 2002;53(3):245–56.

Guex J, Myon E, Didier L, Le Nguyen C, Taieb C. Chronic venous disease: health status of a population and care impact on this health status through quality of life questionnaires. Int Angiol. 2005;24(3):258–64.

Guex J, Avril L, Enrici E, Enriquez E, Lis C, Taïeb C. Quality of life improvement in Latin American patients suffering from chronic venous disorder using a combination of Ruscus aculeatus and hesperidin methyl-chalcone and ascorbic acid (quality study). Int Angiol. 2010;29(6):525–32.

Belczak S, Sincos I, Campos W, Beserra J, Nering G, Aun R. Veno-active drugs for chronic venous disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel-design trial. Phlebology. 2014;29(7):454–60.

Eklof B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, Carpentier PH, Gloviczki P, Kistner RL, et al. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(6):1248–52.

Cospite M, Ferrara F, Cospite V, Palazzini E. Sulodexide and the microcirculatory component in microphlebopathies. Curr Med Res Opin. 1992;13(1):56–60.

Petruzzellis V, Troccoli T, Florio T, Vadalà P. Attivita terapeutica del sulodexide per via orale nell’insufficienza venosa cronica (Therapeutic activity of oral sulodexide in chronic venous insufficiency). G Ital Angiol. 1991;11:139–43.

Scondotto G, Aloisi D, Ferrari P, Martini L. Treatment of venous leg ulcers with sulodexide. Angiology. 1999;50(11):883–9.

Verardi S, Ippoliti A, Ramundo A, Ranucci A, Tozzi A. Medium-term treatment of chronic venous insufficiency with oral sulodexide. Aggior Med Chir. 1993;11(2):230–40.

Luttichau U, Palazzini E. Pharmacological treatment of post-phlebitic syndromes with sulodexide. Med Praxis. 1992;13:1–8.

Kucharzewski M, Franek A, Koziolek H. Treatment of venous leg ulcers with sulodexide. Phlebologie. 2003;32(5):115–20.

Del Guercio R, Siciliano G, Niglio A, Del Guercio M. Valutazioni sull’impiego del sulodexide in un gruppo di pazienti con IVC (Assessment of sulodexide therapy in a group of CVI patients). Minerva Angiol. 1991;16(2):141–2.

Andreozzi G. Sulodexide in the treatment of chronic venous disease. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2012;12(2):73–81.

Acknowledgments

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Dr. Giuseppe D’Ambrosio, Medical Affairs Director, Alfa Wassermann Pharma International. We would also like to thank Therese Chapman, a freelance medical writer, and Nishad Parkar, PhD, of Springer Healthcare Communications, for providing English language editing of the manuscript. This assistance, as well as article publication charges and the open access fee, was funded by Alfa Wassermann.

Investigators and centres that participated in this multicentre trial:

1. Elleuch Nizar - La Rabta University Hospital, Tunis.

2.Rabai Jamila - private practice, Tunis.

3.Gatoufi Mohamed Habib - private practice, Tunis.

4.Ben Jaafar Hichem - private practice, Tunis.

5.Abbouz Nacef - private practice, Tunis.

6.Ben Youssef Jalel - private practice, Bizerte.

7.Boumeftah Saliha - Centre Medical Douane, Tunis.

8.Bziou Adel - private practice, Kef.

9.Bedhiafi Fadhel - private practice, Kef.

10.Drar Hayet - Centre Medical Telecom, Tunis.

11. Mrabet Mohamed Tahar - Centre Medical Telecom, Tunis.

12. Ennaifer Ouajdi - Centre Medical Telecom, Tunis.

13. Jerbi Najib - private practice, Nabeul.

14. Msolly Mohamed Riadh - private practice, Tunis.

15. Chammekh Anis - Centre Medical Douane, Tunis.

16. Ouslati Atef - Centre Medical Douane, Tunis.

17. Bessais Mohamed - private practice, Tunis.

18. Ben Khdija Adel - private practice, Tunis.

19. Hamdane Abdelaziz - private practice, Hammamet.

20. Gharbi Anis - private practice, Tunis.

21.Aissa Ahmed - private practice, Tunis.

22. Farhat Mourad - private practice, Tunis.

23. Akassi Seifeddine - private practice, Tunis.

24. Marzouki Mohamed Saber - private practice, Tunis.

25. Abdi Karim - private practice, Tunis.

26. Jellazi Nabil - private practice, Tunis.

27. Zidi Hichem - private practice, Tunis.

28. Mechergui Mohamed - private practice, Tunis.

29.Sahli Abderrazek - private practice, Tunis.

30. Haddou Chiheb - private practice, Tunis.

31. Kouki Sadok - private practice, Tunis.

32. Hentati Zouheir - private practice, Tunis.

33. Ben Sedrine Bechir - private practice, Tunis.

34. Cherif Fakhreddine - private practice, Tunis.

35. Khosref Mondher - private practice, Tunis.

36. Seghaier Noureddine - private practice, Tunis.

37. Bellamine Zied - private practice, Tunis.

38. Fertani Taher - private practice, Tunis.

39. Hicheri Sabri - private practice, Tunis.

40. Hicheri Moulina - private practice, Tunis.

41. Guerchi Mondher - private practice, Tunis.

42. Ghrib Najeh - private practice, Tunis.

43. Jaidane Wissam - private practice, Tunis.

44. Ben Youssef Kamel - private practice, Tunis.

45. Mekki Laamiri Jamila - private practice, Tunis.

46. Zangar Mohamed - private practice, Nabeul.

47. Belaid Adel - private practice, Nabeul.

48. Hammami Hatem - private practice, Nabeul.

49. Garali Mounir - private practice, Nabeul.

50. Rebah Lamine - private practice, Nabeul.

Disclosures

Elleuch Nizar, Zidi Hichem, Bellamine Zied, Hamdane Abdelaziz, Guerchi Mondher and Jellazi Nabil have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/B8D4F06021CD5E86.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Elleuch, N., Zidi, H., Bellamine, Z. et al. Sulodexide in Patients with Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs: Clinical Efficacy and Impact on Quality of Life. Adv Ther 33, 1536–1549 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0359-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0359-9