Abstract

T and NK cell proliferative diseases associated with acute and chronic Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection are uncommon and raise several clinical issues regarding diagnostic criteria and terminology. This is a summary report of the consensus meeting held in the 4th Asian Hematopathology Workshop. The umbrella term “EBV-positive T/NK lymphoproliferative disease in childhood-type” covers the entire spectrum of EBV-associated lesions in childhood, ranging from reactive to neoplastic processes. Systemic T/NK cell lymphoproliferative disease (LPD) of childhood type is defined as a fulminant disease associated with the proliferation of polyclonal, oligoclonal, or monoclonal T or NK cells and includes aggressive NK cell-associated leukemia in children. Chronic active EBV disease-type T/NK cell LPD is divided into three groups—polymorphic/polyclonal, polymorphic/monoclonal, and monomorphic/monoclonal—based on the histology and clonality of T or NK cells. A monoclonal EBV-positive T/NK cell type of proliferation with the clinical features of chronic active EBV disease rather than the fulminant course of systemic EBV-positive T/NK cell LPD of childhood is considered “chronic active EBV disease-type T/NK cell LPD”. Hydroa vacciniforme (HV)-like T cell LPD is defined as a spectrum of EBV-infected T cell proliferative diseases with homing to the skin and is further classified into a classic type, a severe type, and malignant lymphoma. Criteria to define each category of HV-like T cell LPD remain to be clarified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infects T or NK cells, albeit uncommonly, and can cause benign or severe disease depending on the immunological response of the individual [1–3]. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma and aggressive NK cell leukemia are prototypes of EBV-associated NK/T cell neoplasms, and the diagnostic criteria are well defined in the WHO classification: Tumors of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues [4, 5]. On the other hand, chronic active EBV infections show considerable variations in their biology and pathology when attempting to distinguish between infectious and neoplastic diseases, which lead to difficulties in diagnosis and treatment [6]. Currently, chronic active EBV infection is defined as a systemic illness of greater than 3 or 6 months duration that begins as a primary EBV infection, with histopathological evidence of major organ involvement and increased levels of EBV RNA or proteins in affected tissues or blood [7–9]. Such a definition of chronic active EBV infection is based mainly on clinical and laboratory findings. Chronic active EBV infections are always accompanied by lymphoproliferation to varying degrees. This syndrome is polyclonal, oligoclonal, or monoclonal in nature and can often transform to an obvious T or NK cell lymphoma or to leukemia [8, 10, 11]. Because chronic active EBV infections show a broad spectrum of lymphoproliferation in tissue biopsies [10], there has been debate regarding the application of the term “chronic active EBV infection” to this spectrum of diseases and on the diagnostic criteria for distinguishing them from overt malignant lymphomas.

Other diseases associated with EBV infection raise similar issues. Systemic T cell lymphoproliferative disease (LPD) of childhood and hydroa vacciniforme (HV)-like T cell lymphoma are described in the new WHO classification [12]. Systemic EBV-positive T cell LPD is defined as a clonal proliferation of EBV-infected T cells with an activated CD8-positive cytotoxic phenotype [12, 13]. It can occur shortly after a primary acute EBV infection or in the setting of chronic active EBV infections. Clinical syndromes associated with a cytokine storm are characteristic of this disease and include fulminant hemophagocytic syndrome, pancytopenia, and multiorgan failure [14–16]. Proliferating T cells in this disease should be clonal by definition; however, there have been reports of cases that are polyclonal for T cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement in which the proliferating cells might be NK cells or polyclonal T cells [12, 17, 18].

Hydroa vacciniforme-like T cell lymphomas have been named as such because gross findings of the lesion are similar to those for HV, a self-limited EBV-associated vesiculobullous disease healed with central umbilication [19]. Most patients with HV regress spontaneously, but some develop systemic or cutaneous T or NK cell lymphoma or leukemia [20–23]. The relationship between HV and HV-like T cell lymphoma remains to be clarified and there are no convincing criteria to distinguish between these two conditions. On the other hand, mosquito bite hypersensitivity is a cutaneous manifestation of chronic EBV infection characterized by intense local skin symptoms including erythema, bullae, ulcers, and scar formation and by systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and liver dysfunction after mosquito bites.

As described above, T and NK cell proliferative diseases associated with acute and chronic EBV infections have several issues regarding the diagnostic criteria and terminology. The name of the disease must be finely tuned to reflect its exact biology and diagnostic criteria must be redefined.

The 4th Asian Hematopathology Symposium and consensus meeting

Because the T or NK cell proliferative diseases associated with acute or chronic EBV infection are uncommon even in Asia, it is difficult to study a sufficient number of cases to obtain comprehensive knowledge for each form. Therefore, expert hematopathologists from Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan met in Seoul during the 4th Asian Hematopathology Workshop held on January 29, 2012 with the aim of obtaining a consensus viewpoint for the issues raised. The goal of the meeting was to collect opinions on the terminology and diagnostic criteria for acute and chronic EBV infection-related diseases. In the workshop, expert pathologists presented their work on several topics related to T/NK LPDs associated with chronic and acute EBV infection (Table 1).

Here, the deliberations of the expert panel are presented in response to four key questions.

Systemic EBV-positive T cell LPD of childhood

Question 1: Do you agree with the current diagnostic criteria for systemic EBV-associated T cell LPD of childhood?

None of the experts agreed with the current diagnostic criteria and together proposed the following guidelines.

-

1.

It should include NK cell cases.

-

2.

It should include polyclonal, oligoclonal, and monoclonal cases.

-

3.

The terminology of “childhood” in the current WHO classification might be better changed to “childhood-type” because a similar disease occurs in adults older than 30 years. Usually, systemic EBV-positive LPD with hemophagocytosis in children occurs after the primary EBV infection, but in adult patients, the EBV might arise from a new infection or be activated from a latent infection.

Comment

It was generally agreed that the target for EBV infection in systemic EBV-positive T cell LPD of childhood in Asia is mainly CD8+ cytotoxic T cells [12]. However, EBV infections were also found in other lymphocyte subpopulations of CD4+ T cells and CD16+ NK cells although the frequency was much less than among CD8+ cells [17, 24, 25]. Therefore, the definition of “systemic EBV+ T cell LPD of childhood” should not be limited to T cells and should be expanded to include NK as well as T cells. The clonality of EBV-positive systemic T cell LPD of childhood is determined by various methods including assays for TCR gene rearrangements and cytogenetic abnormalities, and EBV genome terminal repeat investigation. The rate of cytogenetic abnormalities has been reported as 30 % [18]. Among patients with acute hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, EB viral monoclonality was detected in more than 80 % of cases. Imashuku et al. analyzed EBV clonality by Southern blot analysis and EBV was monoclonal in 21 patients, biclonal in 2 patients, and non-clonal in 2 patients among 25 patients [18, 25]. TCR gene rearrangement has been detected in about 33–100 % of cases. By using Southern blot analysis, 17 among 25 patients showed monoclonality for TCR genes; ten patients for TCR beta chain gene, three patients for TCR-gamma chain gene, and two patients for both beta and gamma chain genes. Matsuda et al. reported that all six patients showed monoclonal peaks in TCRβ and/or TCRγ using European BIOMED-2 multiplex PCR. Ahn et al. showed monoclonal TCR-gamma gene rearrangement in 10 among 30 patients by conventional PCR method. [18, 25–27].

The absence of clonality detected from TCR gene rearrangements does not necessarily mean a non-clonal disease but more likely indicates NK cell proliferation. Although EBV clonality is more reliable method to identify clonality of EBV-positive disease, EBV clonality is difficult to analyze routinely because the technique needs fresh samples with large amounts of DNA for Southern blotting. Importantly, clonality defined by TCR gene rearrangement and EBV gene terminal repeats has little clinical impact in terms of the outcomes for patients. The overall clinical, laboratory, and pathology findings are similar irrespective of T cell and EBV clonality [18].

Question 2: Is aggressive NK cell leukemia an NK cell counterpart of systemic T cell LPD of childhood?

In response to this question, the experts agreed that it might be true in young children but not in adult patients. The EBV-infected cells in cases of systemic T cell LPD in younger children are mainly CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, but in a minority of cases the EBV infects NK cells or CD4+ cells [25]. Systemic EBV+ NK cell proliferation in children can be called “aggressive NK cell leukemia.” Such EBV-positive T/NK cell LPD in childhood arises on a background of primary EBV infection.

Aggressive NK cell leukemia in adult patients shares clinical similarities with systemic T cell LPD in children, but there are some differences. Pathologically infiltrating cells in systemic T cell LPD of childhood are usually small and lack significant cytologic atypia, while aggressive NK cell leukemia in adult patients commonly show obvious cytologic atypia of tumor cells with significant cytogenetic abnormalities [4]. Aggressive NK cell leukemia in adult has no relation with primary EBV infection but caused by reactivation or reinfection of EBV in the elderly patients.

Chronic active EBV infection of T and NK cells

Question 3: What is the best nomenclature to describe the clinicopathological spectrum of chronic active EBV infections?

Regarding this question, some experts favored “EBV-positive T/NK cell LPD in childhood.” Others suggested the term “chronic active EBV disease” rather than “infection” because it is not a simple infection but an LPD induced by EBV infection. Finally, “chronic active EBV disease-type T/NK cell LPD” was adopted as the most appropriate term.

Comment

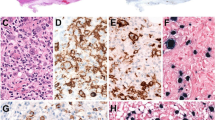

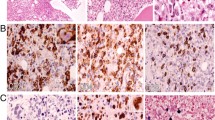

Chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV) of T and NK cell type is always associated with proliferation of T or NK cell to varying degrees [8, 10, 11]. The proliferating cells in cases of CAEBV frequently lack histological evidence of malignancy and can be polyclonal, oligoclonal, or monoclonal according to the stage of transformation [10]. Because CAEBV constitutes a continuous spectrum of EBV-infected T/NK cell proliferation, nomenclature to describe the pathological category of CAEBV is needed to facilitate communication among clinicians and pathologists. Ohshima et al. proposed a three-tier classification for CAEBV diseases [8]. Category A1 is polymorphic LPD with polyclonal proliferation of EBV-infected T or NK cells. Category A2 is polymorphic LPD with proliferation of monoclonal T or NK cells. Category A3 is monomorphic LPD of monoclonal T or NK cells and is equivalent to EBV-associated T/NK lymphoma/leukemia (Table 2). Experts agreed to accept this three-tier classification for the diagnosis of CAEBV disease. Categories A2 and A3 might correspond to systemic T cell LPD of childhood arising in patients with CAEBV disease in the current WHO classification [12].

Hydroa vacciniforme and hydroa-like T cell lymphoma

Question 4: What are the diagnostic criteria that can distinguish HV from HV-like lymphoma?

The experts concluded that there are no reliable criteria to separate HV from HV-like T cell lymphoma because they constitute a continuous spectrum of diseases and proposed the nomenclature “Hydroa-like T cell LPD of childhood type.”

Comment

HV has been divided into two types based on the clinical features [28, 29]. The classic type is a self-limited form of disease characterized by the formation of vesicles on sun-exposed areas and follows a benign course, typically resolving in adolescence or young adulthood [29, 30]. Patients with the severe type tend to show more extensive skin lesions and these are often complicated by chronic active EBV infection. About half of patients with severe HV develop EBV-associated NK/T cell lymphomas in the skin or other organs 2–14 years after onset [29]. Hydroa-like T cell lymphomas develop in patients with long-standing hydroa vacciniforme [21, 29] but may also occur as a de novo disease [19, 31, 32]. Severe HV and HV-like T cell lymphoma show significant overlapping in their histopathology. As the disease progresses to overt malignancy, the cutaneous lesions are more extensive and deeper and the infiltrating cells show an increasing incidence of T cell monoclonality. Considering the continuous spectrum of HV-like T cell LPD, the distinction of HV-like T cell lymphoma from severe HV is arbitrary and very difficult. However, for clinical practice and investigations, the disease would be better to be stratified according to the severity, pathological changes, and clonality of cells. Consensus on the diagnostic criteria to define each category of HV-like T cell LPD should be made in the near future.

Conclusions

At the end of the meeting, the experts proposed a nomenclature for EBV-positive T/NK LPD of childhood as in Table 3. Since each category of EBV+ T/NK LPD in childhood has been defined based on the clinical characteristics, clinical features were considered as a part of the disease definition. Under the umbrella term “EBV-associated T/NK LPD,” which covers the entire spectrum of EBV-associated lesions in childhood from reactive to neoplastic process, the disease was divided into systemic and cutaneous forms. Systemic T/NK cell LPD of childhood is a fulminant disease associated with proliferation of polyclonal, oligoclonal, or monoclonal T or NK cells and aggressive NK cell leukemia in children can be included in this category. Chronic active EBV disease-type T/NK cell LPD is a systemic illness lasting more than 3 months with histopathological evidence of major organ involvement and increased levels of EBV RNA or proteins in affected tissues or blood. CAEBV disease-type T/NK cell LPD is divided into three groups based on the histology and clonality of T or NK cells. A monoclonal EBV+ T/NK cell proliferation with the clinical features of CAEBV rather than the fulminant course of systemic EBV-positive T/NK cell LPD of childhood is best regarded as CAEBV disease-type T/NK cell LPD.

Mosquito bite hypersensitivity and hydroa vacciniforme-like T cell LPD constitute cutaneous form of EBV-positive LPD in childhood. Since two entities are distinct in the clinical characteristics and the lineage of infiltrating cells, they are worth specifically named in the classification of EBV-positive T/NK LPD.

References

Iwatsuki K, Yamamoto T, Tsuji K, Suzuki D, Fujii K, Matsuura H, Oono T (2004) A spectrum of clinical manifestations caused by host immune responses against Epstein–Barr virus infections. Acta Med Okayama 58:169–180

Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, Ko YH, Jaffe ES (2009) Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8–9 September 2008. Ann Oncol 20:1472–1482

Jones JF, Ray CG, Minnich LL, Hicks MJ, Kibler R, Lucas DO (1985) Evidence for active Epstein–Barr virus infection in patients with persistent, unexplained illnesses: elevated anti-early antigen antibodies. Ann Intern Med 102:1–7

Chan JKC, Jaffe ES, Ralfkiaer E, Ko YH (2008) Aggressive NK-cell leukaemia. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW (eds) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, pp 276–277

Chan JKC, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Ferry JA, Peh SC (2008) Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW (eds) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, pp 285–288

Kimura H (2006) Pathogenesis of chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection: is this an infectious disease, lymphoproliferative disorder, or immunodeficiency? Rev Med Virol 16:251–261

Shibata Y, Hoshino Y, Hara S, Yagasaki H, Kojima S, Nishiyama Y, Morishima T, Kimura H (2006) Clonality analysis by sequence variation of the latent membrane protein 1 gene in patients with chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. J Med Virol 78:770–779

Ohshima K, Kimura H, Yoshino T, Kim CW, Ko YH, Lee SS, Peh SC, Chan JK (2008) Proposed categorization of pathological states of EBV-associated T/natural killer-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) in children and young adults: overlap with chronic active EBV infection and infantile fulminant EBV T-LPD. Pathol Int 58:209–217

Okano M, Kawa K, Kimura H, Yachie A, Wakiguchi H, Maeda A, Imai S, Ohga S, Kanegane H, Tsuchiya S, Morio T, Mori M, Yokota S, Imashuku S (2005) Proposed guidelines for diagnosing chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. Am J Hematol 80:64–69

Ohshima K, Suzumiya J, Sugihara M, Nagafuchi S, Ohga S, Kikuchi M (1998) Clinicopathological study of severe chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection that developed in association with lymphoproliferative disorder and/or hemophagocytic syndrome. Pathol Int 48:934–943

Kimura H, Hoshino Y, Kanegane H, Tsuge I, Okamura T, Kawa K, Morishima T (2001) Clinical and virologic characteristics of chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection. Blood 98:280–286

Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kimura H, Jaffe ES (2008) EBV-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of childhood. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW (eds) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, pp 278–280

Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, Reyes E, Teruya-Feldstein J, Kingma DW, Sorbara L, Raffeld M, Straus SE, Jaffe ES (2000) Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood 96:443–451

Chuang HC, Lay JD, Chuang SE, Hsieh WC, Chang Y, Su IJ (2007) Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) latent membrane protein-1 down-regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) receptor-1 and confers resistance to TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in T cells: implication for the progression to T-cell lymphoma in EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Pathol 170:1607–1617

Lay JD, Tsao CJ, Chen JY, Kadin ME, Su IJ (1997) Upregulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene by Epstein–Barr virus and activation of macrophages in Epstein–Barr virus-infected T cells in the pathogenesis of hemophagocytic syndrome. J Clin Invest 100:1969–1979

Su IJ, Wang CH, Cheng AL, Chen RL (1995) Hemophagocytic syndrome in Epstein–Barr virus-associated T-lymphoproliferative disorders: disease spectrum, pathogenesis, and management. Leuk Lymphoma 19:401–406

Fox CP, Shannon-Lowe C, Gothard P, Kishore B, Neilson J, O’Connor N, Rowe M (2010) Epstein–Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults characterized by high viral genome load within circulating natural killer cells. Clin Infect Dis 51:66–69

Imashuku S, Hibi S, Tabata Y, Itoh E, Hashida T, Tsunamoto K, Ishimoto K, Kawano F (2000) Outcome of clonal hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: analysis of 32 cases. Leuk Lymphoma 37:577–584

Magana M, Sangueza P, Gil-Beristain J, Sanchez-Sosa S, Salgado A, Ramon G, Sangueza OP (1998) Angiocentric cutaneous T-cell lymphoma of childhood (hydroa-like lymphoma): a distinctive type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 38:574–579

Wu YH, Chen HC, Hsiao PF, Tu MI, Lin YC, Wang TY (2007) Hydroa vacciniforme-like Epstein–Barr virus-associated monoclonal T-lymphoproliferative disorder in a child. Int J Dermatol 46:1081–1086

Oono T, Arata J, Masuda T, Ohtsuki Y (1986) Coexistence of hydroa vacciniforme and malignant lymphoma. Arch Dermatol 122:1306–1309

Iwatsuki K, Ohtsuka M, Akiba H, Kaneko F (1999) Atypical hydroa vacciniforme in childhood: from a smoldering stage to Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoid malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol 40:283–284

Cho KH, Lee SH, Kim CW, Jeon YK, Kwon IH, Cho YJ, Lee SK, Suh DH, Chung JH, Yoon TY, Lee SJ (2004) Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative lesions presenting as a hydroa vacciniforme-like eruption: an analysis of six cases. Br J Dermatol 151:372–380

Kasahara Y, Yachie A, Takei K, Kanegane C, Okada K, Ohta K, Seki H, Igarashi N, Maruhashi K, Katayama K, Katoh E, Terao G, Sakiyama Y, Koizumi S (2001) Differential cellular targets of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection between acute EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and chronic active EBV infection. Blood 98:1882–1888

Kimura H, Ito Y, Kawabe S, Gotoh K, Takahashi Y, Kojima S, Naoe T, Esaki S, Kikuta A, Sawada A, Kawa K, Ohshima K, Nakamura S (2012) EBV-associated T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases in nonimmunocompromised hosts: prospective analysis of 108 cases. Blood 119:673–686

Ahn JS, Rew SY, Shin MG, Kim HR, Yang DH, Cho D, Kim SH, Bae SY, Lee SR, Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee JJ (2010) Clinical significance of clonality and Epstein–Barr virus infection in adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Hematol 85:719–722

Matsuda K, Nakazawa Y, Yanagisawa R, Honda T, Ishii E, Koike K (2011) Detection of T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in children with Epstein–Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis using the BIOMED-2 multiplex polymerase chain reaction combined with GeneScan analysis. Clin Chim Acta 412:1554–1558

Gu H, Chang B, Qian H, Li G (1996) A clinical study on severe hydroa vacciniforme. Chin Med J (Engl) 109:645–647

Iwatsuki K, Satoh M, Yamamoto T, Oono T, Morizane S, Ohtsuka M, Xu ZG, Suzuki D, Tsuji K (2006) Pathogenic link between hydroa vacciniforme and Epstein–Barr virus-associated hematologic disorders. Arch Dermatol 142:587–595

Gupta G, Man I, Kemmett D (2000) Hydroa vacciniforme: a clinical and follow-up study of 17 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 42:208–213

Cho KH, Kim CW, Lee DY, Sohn SJ, Kim DW, Chung JH (1996) An Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative lesion of the skin presenting as recurrent necrotic papulovesicles of the face. Br J Dermatol 134:791–796

Barrionuevo C, Anderson VM, Zevallos-Giampietri E, Zaharia M, Misad O, Bravo F, Caceres H, Taxa L, Martinez MT, Wachtel A, Piris MA (2002) Hydroa-like cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 16 pediatric cases from Peru. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 10:7–14

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Elaine S. Jaffe (Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) for her comment on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, YH., Kim, HJ., Oh, YH. et al. EBV-associated T and NK cell lymphoproliferative disorders: consensus report of the 4th Asian Hematopathology Workshop. J Hematopathol 5, 319–324 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-012-0169-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-012-0169-1