Abstract

Autogenic processes are widely found in various sedimentary systems and they play an important role in the depositional evolution and corresponding sedimentary architecture. However, autogenic processes are often affected by changing allogenic factors and are difficult to be identified and analyzed from modern and ancient records. Through the flume tank experiment under constant boundary conditions, the depositional process, evolution principles, and the sedimentary architecture of a river-dominated delta was presented, and a corresponding sedimentary architecture model was constructed. The evolution of river-dominated delta controlled only by autogenic process is obviously periodic, and each autogenic cycle can be divided into an initial progradational stage, a middle retrogratational stage, and a late aggradational–progradational stage. In the initial progradational stage, one feeder channel incised into the delta plain, mouth bar(s) was formed in front of the channel mouth, and small-scale crevasse splays were formed on the delta plain. In the middle retrogradational stage, the feeder channel was blocked by the mouth bar(s) which grew out of water at the end of the initial stage, and a set of large-scale distributary splay complexes were formed on the delta plain. These distributary splay complexes were retrogradationally overlapped due to the continuous migration of the bifurcation point of the feeder channel. In the late aggradational–progradational stage, the feeder channel branched into several radial distributary channels, overlapped distributary channels were formed on the delta plain, and terminal lobe complexes were formed at the end of distributary channels. The three sedimentary layers formed in the three stages constituted an autogenic succession. The experimental delta consisted of six autogenic depositional successions. Dynamic allocation of accommodation space and the following adaptive sediments filling were the two main driving factors of the autogenic evolution of deltas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There are a number of controlling factors that govern the depositional processes and the internal architecture of a sedimentary system including water and sediment supply, climatic changes, base-level variation, tectonic activities, and so on (Gong et al. 2016; Jia et al. 2018; Jia et al. 2016; Ventra et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2018a; Zhao et al. 2018b). In order to clarify the controlling mechanism of each factor on the sedimentary system, Beerbower (1964) first classified the above factors into two types, including within-basin and extra-basin factors. The periodic and spontaneous evolution of geomorphology has been observed in most of the terrestrial sedimentary systems (such as alluvial fan, fluvial delta, braided river, and meandering river) when the extra-basin factors were maintained approximately constant (Carlson et al. 2018; Clarke et al. 2010; de Haas et al. 2016; Hajek and Straub 2017, 2017; Hamilton et al. 2013; Trampush et al. 2017; Van Dijk et al. 2009). As controlled by the within-basin factors only, the above processes are called autogenic processes (Miall et al. 2014). The widely existing fining upward sequence in the meandering river reservoir and the coarsening upward sequence in the delta are typical autogenic deposits (Hajek and Straub 2017; Miall et al. 2014).

Autogenic processes control the fundamental deposition of the sedimentary system, such as channel migration, avulsion, and abandonment (Clarke et al. 2010; Qi et al. 2018). It is these basic processes that give rise to the growth of sedimentary systems and to a large extent determine the internal sedimentary architecture. Even though an autogenic process only exists in a relatively short time compared to the allogenic process, the deposits formed in autogenic process get recorded in the stratigraphic framework created by the allogenic process (Hamilton et al. 2013; Miall et al. 2014). In other words, the autogenic deposits are the basic elements of the stratigraphy (Li et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2013). Therefore, it is not only helpful to guide the evaluation and development of oil and gas reservoirs scientifically, but also essential for sedimentology research to clarify the autogenic sedimentary process and its controlling effect on the internal architecture of sedimentary systems.

The autogenic depositional processes and the associated sedimentary mechanism have received extensive attention and have been thoroughly researched. As described by Hajek and Straub (2017), the typical autogenic processes include dune migration, upstream migrating cyclic steps, channel migration/meandering, channel bifurcation, avulsion, and regrading of depositional surface. All these processes are very common in modern sedimentary systems and stratigraphy records (de Haas et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2018a, b). For a sedimentary system, when the allogenic boundary condition is constant or approximately stable, its topography and sedimentary architecture is completely dominated by the autogenic processes (Clarke et al. 2010; Hajek and Straub 2017; Van Dijk et al. 2009).

In general, autogenic behavior is usually observed during allogenic variations in field, which makes it difficult to study its characteristics and significance (Van Dijk et al. 2009). In order to clarify the autogenic depositional process and associated internal architecture of sedimentary system, flume tank experiments have been performed by researchers on various sedimentary systems in recent years (Carlson et al. 2018; Esposito et al. 2018; Trampush et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2016). To date, extensively experimental studies have been performed to investigate the autogenic behavior of alluvial fans, fan deltas, meandering rivers, and so on (Clarke et al. 2010; Clarke 2015, 2014; Crosato et al. 2011; van Dijk et al. 2013; Egozi and Ashmore 2009; Ganti et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2013; Nicholas et al. 2009; Paola et al. 2009; Reitz and Jerolmack 2012; Van Dijk et al. 2009). As pointed out in a review by Paola et al. (2009), flume tank experiments produce spatial structure and kinematics that, although imperfect, compare well with natural systems despite differences of spatial scale, time scale, material properties, and number of active processes (Hajek and Straub 2017). Therefore, the experimental sedimentary systems can be regarded as a substitution of the field scaled ones. In recent years, flume experiments were used for investigating the autogenic process of fan delta (Van Dijk et al. 2009), fluvial delta (Foreman and Straub 2017; Carlson et al. 2018) using non-cohesive sediment and constant sea level (not constant relative base level). These types of sedimentary systems usually developed in arid and semiarid climate. In humid climate, the sediment in various types of sedimentary systems was cohesive. However, the experimental studies on autogenic process-controlled river-dominated deltas using cohesive sediment and constant relative base level are very limited (Straub et al. 2015). For river-dominated delta, even though its extreme complex sedimentary architecture was investigated by numerous studies using outcrops, modern deltas, and numerical models (Wright 1977; Edmonds and Slingerland 2007; Ahmed et al. 2014), but the autogenic successions included in the sedimentary records were affected by changing boundary conditions (Wellner et al. 2004). The formation process and mechanism of the mouth bar in the delta was investigated by numerous scholars by numerical simulation and field work (Wright 1977; Edmonds and Slingerland 2007; Ahmed et al. 2014), but these studies only focused on mouth bar or a part of river-dominated deltas. Thus, the complete and detailed sedimentary architecture of an entire delta was not clear enough yet. Therefore, the autogenic evolution of depositional process and associated internal architecture of cohesive sediment-dominated deltas in an unconfined catchment still need to be investigated.

In this paper, we investigated the spontaneous sedimentation and evolution in the autogenic processes of cohesive sediment-dominated deltas based on the experiment performed at Tulane University by Straub et al. (2015). The entire process during the formation of the experimental delta had been recorded with a digital camera and a 3D laser scanner. The digital elevation models (DEMs) had been constructed with scanned topography data and were utilized for topography and sedimentary evolution analysis with the assistance of a newly developed program. Based on the analysis of the autogenic process and the internal architecture of the experimental delta, six autogenic cycles have been identified.

2 Experimental design

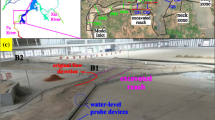

To investigate the autogenic behavior during a river-dominated delta evolution, an experiment in the Delta Basin at Tulane University was performed by Straub et al. (2015). In order to simulate the autogenic depositional process, consistent accommodation was created at a constant rate by increasing the ocean level using a motorized weir that was in hydraulic communication with the basin (Straub et al. 2015). The facility diagram of the experiment is shown in Fig. 1. The boundary conditions (Table 1) including the computer-controlled ocean level rise rate (r), input water (QW), and sediment discharge (QS) allowed the shoreline to be maintained at an approximately constant location in the whole experiment but with superimposed fluctuations associated with autogenic processes (Straub et al. 2015). The particle size of sediments ranged from 1 to 1000 μm with a mean of 67 μm and it was dominated by quartz. During the first 300 h, a bedform for the experiment was constructed (Straub et al. 2015). The polymer enhanced the cohesion of the input sediments and ensured the formation of deltas with strong channelization at subcritical Froude numbers (Straub et al. 2015). After finishing the bedform, the experiment was run for 700 h with the weakly cohesive sediment (Straub et al. 2015). Red dye was added into the water to indicate the active flow and basin water.

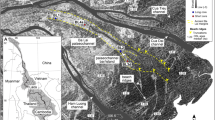

Digital elevation models (DEMs) with a set of 5 × 5 mm2 horizontal grids were constructed with a 3D laser scanner (Fig. 1). The vertical resolution for terrestrial regions and areas with water depths < 50 mm was less than 1 mm. The topographic data (sediment thickness) were collected once an hour during the whole experiment (1000 h) and share the same reference system (Fig. 2). Therefore, the spatial and temporal resolution was fine enough to capture the mesoscale morphodynamics and internal architecture for the delta (e.g., distributary channels, lobes, levees, and crevasse splays). To aid the analysis of the depositional process and the sedimentary architecture, the digital images of the delta top were collected every 15 min.

To understand the evolution of the depositional process and the resulting sedimentary architecture of the experimental delta, we developed a program with MATLAB for the analysis of the DEMs. With the help of the program, four sections across the flow direction and one section along the radial flow direction were figured (Fig. 2).

3 Result

3.1 The periodicity and general characteristics of the autogenic depositional process

The autogenic processes were constrained under the constant boundary condition during the experiment. The water and sediment supply, the total accommodation space, and relative base level remain stable (Hajek and Straub 2017). Therefore, the variation of depositional process and the complex internal sedimentary architecture were spontaneously formed. In the experiment, the spontaneous periodic evolution of the delta has been observed.

3.1.1 Periodically vertical transition of sedimentary architecture elements

To check the topography variations in the whole experiment, a transverse section was constructed with the data of the DEMs using the newly programed application (Fig. 3). Six kinds of sedimentary architecture elements were observed in the evolution of the delta, including feeder channel, levee, mouth bar, distributary splay, terminal lobe, and distributary channel. As observed from the transverse profile, the vertical distribution of these sedimentary architecture elements was periodic and occurred in a fixed order (Fig. 3). From bottom to top, six cycles of sedimentary architecture element transition could be observed. Each cycle consisted of a lower part, a middle part, and an upper unit. On the transverse profile, the lower part was characterized by feeder channel and associated levees, the middle part was characterized by distributary splays, and the upper part was characterized by distributary channels and associated terminal lobes (Fig. 3). The three parts constituted a complete succession controlled by constant boundary conditions. In this experiment (301–700 h), there were six sequentially stacked such successions. Sequential transition of the three parts indicated the periodicity of autogenic processes.

Topography (sediment thickness) evolution from 301 to 1000 h along the transverse section. The locations of section L3–R3 are presented in Fig. 2

3.1.2 Periodic evolution of delta geomorphological characteristics

In order to further demonstrate the periodicity of delta evolution, the geomorphological characteristics have been investigated based on the data published by Straub et al. (2015). There are three key indicators for the characterization of delta geomorphology, including the terrestrial delta area (ATD), the fraction of the delta top covered by active flow (fW), and the roughness of the shoreline (RSL) (Fig. 4). The ATD curve demonstrated that the shoreline was well-controlled by the automatic water-level controller (Fig. 1), as we expected. The nearly constant ATD ensured the stability of the accommodation in the depositional environment because the shoreline was maintained at an approximately constant location (Straub et al. 2015).

Evolution of geomorphological characteristics in the autogenic processes. Data of the terrestrial delta area (ATD), the fraction of the delta top covered by active flow (fW), and the roughness of shoreline (RSL) are calculated by Straub et al. (2015)

The fraction of the delta top covered by active flow (fW) is an indicator of the development degree of the channels on the top of the experimental delta. Meanwhile, the roughness of shoreline (RSL) quantified the fluctuations of the shoreline along the delta plain (Straub et al. 2015). In an autogenic process, fW experienced several cycles of rising first and then falling. On the contrary, RSL experienced several cycles of falling first and then rising. It was worth noting that the trends of fW and RSL were exactly the opposite. Both curves of fW and RSL suggested that the geomorphological characteristics (including development degree of channels and the roughness of the shoreline) in the delta had obvious periodic changes under the control of autogenic process (Fig. 4b–c). The spontaneous periodic evolution in distributary channel development degree and shoreline roughness demonstrated that the autogenic processes were very complex rather than simple and stable.

3.1.3 Geomorphology dynamics in the autogenic processes

It was observed that there were six sedimentary cycles driven by the autogenic process in the experiment. According to the evolution of fW and RSL of the experimental delta, deposition on the delta experienced a sequential variation in each cycle, and each cycle was similar (Fig. 4b, c). The whole delta was constituted by the deposition of six such cycles. Therefore, investigation on the depositional process and associated sedimentary evolution in each cycle is essential to understand the nature of geomorphology dynamics of the delta driven by autogenic processes.

The digital images collected during the experiment were utilized to investigate the variations in the cycles. To illustrate the sedimentary evolution in a complete cycle, we choose the cycle formed from 559 to 706 h (Fig. 5). The evolution of the delta which experienced three different stages was manifested in the diversity of its topography and sedimentary elements development.

Geomorphology dynamics and sedimentary elements diversity in different stages of an autogenic cycle. a–b The topography and sedimentary characteristics of the delta at the initial stage, the progradational mouth bar was the main deposit at this stage, most of the sediments were deposited at delta front. c–e. The topography and sedimentary characteristics of the delta at the middle stage, retrogradational distributary splays were the dominant deposits at this stage. Most of the sediment was deposited on delta plain. f The topography and sedimentary characteristics of the delta at the late stage, aggradational distributary channel deposits on delta plain and the associated terminal lobe complexes at the margin of the delta plain were the main deposits during this stage. The red area was covered by flow or basin water because red dye was added into the water to indicate the flow path and basin water during the experiment. Therefore, delta plain and delta front can be identified based on image color

At the initial stage, a feeder channel incised into the delta plain and continuously brought sediments to the delta front. Under continuous sediment feeding, a lobe-shaped mouth bar was formed and grew continuously (Fig. 5a, b). The middle stage of an autogenic cycle was characterized by retrogradational distributary splays (Fig. 5c, e). During the late stage, the feeder channel branched into several small-scale distributary channels, and each of these distributary channels fed a terminal lobe at the distal part of the delta plain (Fig. 5f).

3.2 Geomorphology dynamics and associated internal architecture during different stages

3.2.1 The initial progradational stage

In this stage, the feeder channel deeply incised into the delta plain (Fig. 5a, b), and at the same time, a number of crevasse channels and the associated splays were developed on both sides of the feeder channel. Most of the sediments were transported to the delta front by the strong current in the channel (Fig. 6). As a result, a lobe-shaped channel mouth bar was formed (Fig. 7), and this mouth bar continued to grow under the continuous feeding of the incised channel (Figs. 6 and 7). The mouth bar in the delta front was the dominant deposition formed during this stage. As the mouth bar gradually protruded from the shoreline, RSL of the delta plain increased (Fig. 4c) while fw decreased (Fig. 4b).

Growing process of the mouth bar during the initial stage. Water depth of channel mouth was gradually becoming shallower with the continuous sediments feeding. The location of the images is presented in Fig. 5a

To investigate the sedimentary characteristics on the delta plain during the initial stage, the sediment thickness increment per 7 h’ deposition is calculated and shown in Fig. 8. Compared to the delta front, the deposition rate on the delta plain was significantly lower (Figs. 8 and 9). During the 35 h’ deposition, increment in sediment thickness along the longitudinal section was about only 4 mm in average (Figs. 9 and 10). However, its evolution on the delta plain was unexpectedly complicated (Fig. 8).

Sediment thickness curves from 589 to 624 h during the initial stage on a longitudinal section (Fig. 2 L5–R5). The average slope of delta plain was about 0.5450. Increment of sediment thickness was about 4 mm in average. Most of the deposition located at the middle part of delta plain. The location of the section is presented in Fig. 2

Sediment thickness curves from 589 to 624 h during the initial stage along the transverse sections. The location of the four sections is presented in Fig. 2. Lateral migration of the feeder channel was obviously observed. Crevasse splays were the main deposition on delta plain. Deposition on the area far away from the feeder channel was very limited and even ignorable

According to the observation on digital images and the DEMs, the incised channel was relatively stable; meanwhile, deposition on the delta plain was characterized by crevasse channels and associated crevasse splays (Fig. 8). At the beginning of this stage, only one or a limited number of isolated crevasse splays developed on the delta plain (Fig. 8a, b), and the development degree of levee was too low to be identified (Fig. 8a, b). With the development of the mouth bar in the delta front, the area, quantity, and sediment thickness increment in the crevasse splays on delta plain increased gradually (Figs. 6 and 8). At the end of the initial stage, the crevasse splays were laterally overlapped rather than isolated (Fig. 8d, e). Overlapped map of the areas that has an increment more than 3 mm in A-E demonstrated that most of the sedimentation on the delta plain during the initial stage were deposited at the later hours. Meanwhile, there were nearly no sediments deposited in a large fraction of the delta plain (Figs. 8f and 10). In the latter 21 h during this stage, levees tended to develop well by usually distributing along the channel bank continuously (Fig. 8c, e) and were about 0.25 m wide (Fig. 9).

It was worth noting that the feeder channel was laterally migrating during this stage (Fig. 10). The maximum migration distance was about 0.06 m. The crevasse splays were distributed on the side that was eroded by the migrating feeder channel (Fig. 10a–c).

3.2.2 The middle retrogratational stage

The middle stage started at the end of the initial stage and was characterized by retrogradational distributary splays (Fig. 11). At the end of the initial stage, the mouth bar grew out of water. Consequently, the current started to be blocked by the mouth bar. Meanwhile, the feeder channel continuously transported the sediments to its terminal and bifurcated into a set of small channels (Fig. 12). As a result, a large splay fed by multiple small channels was formed on the delta plain (Fig. 5c). In this paper, the large-scale splay was defined as distributary splay based on its formation process. The deposited distributary splay blocked the subsequent flow. Therefore, a chain reaction was triggered, that is, a distributary splay blocked the subsequent water flow and a new distributary splay was formed. During the chain reaction, several large distributary splays were formed step by step, whose bifurcation points traced back to the source gradually (Fig. 11a–c). When the bifurcation point reached the source point, the middle stage went to its end (Fig. 11c). During this stage, the small channels were shallow and had a short development duration. Nearly no channel filling deposits of such channels could be found in the transverse profile (Fig. 3).

Development of retrogradational distributary splay on delta plain during the middle stage. Distributary splays formed at the end of the feeder channel. As the bifurcation point gradually migrated to the source, the distributary splays were retrogradational from the delta head to the source, step by step

To clarify the precise sediment distribution during the middle stage, the sediment thickness increment per 5 h is calculated and shown in Fig. 12. In each of the increment plot of sediment thickness, the distributary splays were symmetrically distributed on both sides of the feeder channel (Fig. 12). The shape of distributary splay complexes was often short elliptical or irregularly lobate, and several smaller and nearly paralleled small channels developed in the complexes (Figs. 11 and 12b). Compared to the crevasse splays formed during the initial stage, the distributary splays were obviously larger in area and thickness. The distributary splay complexes formed in 5 h were as large as 0.35 m2 in average, and the maximum thickness of the splays in 5 h was thicker than 10 mm (Fig. 12).

The feeder channel was filled while bifurcation point migrated from the channel mouth to the source. The longitudinal topography section from L5 to R5 in this stage indicated that the retrogradational process of the distributary splays and channel filling was continuous rather than eventual (Fig. 13). Channel filling took place and the distributary splay was formed as well (Figs. 11, 12a–e and 14). As the feeder channel was gradually filled from the channel mouth to the source during this stage, the distal part of the channel was filled without lateral migration, while the unfilled reach of the feeder channel still migrated laterally for about 0.055 m during this stage (Fig. 14).

Sediment thickness curves from 625 to 650 h during the middle stage on a longitudinal section (Fig. 2 L5–R5). The average slope of delta plain was about 0.3836. Increment in sediment thickness was about 20 mm in average. The majority of the deposition was located at the middle part of delta plain. The location of the section is presented in Fig. 2

Sediment thickness curves from 625 to 650 h during the middle stage along the transverse sections. The location of the four sections is presented in Fig. 2. Lateral migration of the feeder channel was only observed in the proximal sections (a, b). Distributary splays were the main deposition on delta plain. Sedimentation covered nearly all the delta plain

Retrogradational distributary splays formed during this stage nearly covered the whole delta plain (Fig. 12f), and the average sediment thickness increment during this stage was about 20 mm on delta plain (Fig. 13). Therefore, at this stage, sedimentation mainly occurred on the delta plain, and the fraction of the delta top covered by active flow (fW) was larger than the initial stage (Fig. 3b). The distributary splays were fed by multiple small channels, each of these small channels dominated a single small splay. Consequently, the edge of the large splays was very rough. As the delta plain consisted of a set of retrogradational distributary splays, it had a larger RSL than that in the initial stage (Fig. 3c).

3.2.3 The late aggradational–progradational stage

In the late stage, delta morphology was characterized by the distributary channels originating from the source (Fig. 15). Once the feeder channel entered the delta plain from the source, it quickly bifurcated into multiple small radial distributary channels, and these distributary channels migrated laterally on the delta plain (Fig. 15). The bifurcation and evolution of channel in the late stage was significantly different from the previous two stages.

For each distributary channel, a lobe was formed at the terminal of it (Fig. 15). To clarify the distribution law of sediment in this stage, the sediment thickness increment was calculated per 5 h (Fig. 16). Result shows that the deposition was mainly developed at the terminal of distributary channels (Fig. 16a–e). The areas where most of the sediment were preserved were generally lobe-shaped and distributed near the shoreline (Fig. 15). Therefore, these lobe-shaped sedimentary elements were named as the terminal lobe. In general, terminal lobes were laterally stacked to constitute a terminal lobe complex (Fig. 16a–e).

Compensatory deposition on the top of the delta was typical at this stage (Fig. 16). According to the observation on the distributary channels, the average existence duration of a distributary channel was about 3 h in this experiment. On the contrary, the existence of the feeder channel in the initial stage usually lasted for more than 30 h. The existence duration was significantly less than that of the feeder channel in the initial stage. While a distributary channel reached its end, another one was formed in relatively lower areas. The rapid changes of the distributary channels and associated terminal lobes covered the whole delta during this stage, and as a result, the sediment covered the entire delta approximately uniformly (Fig. 16f). On the longitudinal topography section (L5-R5), the increment in the topography was approximately uniform (Fig. 17). All the above sedimentary characteristics differed greatly from the initial and middle stages.

Sediment thickness curves from 660 to 685 h during the late stage on a longitudinal section (Fig. 2 L5–R5). The average slope of delta plain was about 0.3836. Increment in sediment thickness was about 20 mm in average. The majority of the deposition was located at the middle part of delta plain. The location of the section is presented in Fig. 2

According to the transverse topography sections, the increment in sediment thickness in 25 h’ experiment was significantly thicker than that in 35 h’ experiment in the initial stage (Figs. 10 and 18). Meanwhile, the increment in sediment thickness in the late stage was obviously thinner than that in the middle stage (Figs. 14 and 18). Therefore, we can infer that the deposition in this stage mainly occurred at the delta plain and delta front. The dominant sedimentary elements were the terminal lobe complexes (Figs. 15 and 16).

Sediment thickness curves from 660 to 685 h during the late stage along the transverse sections. The location of the four sections is presented in Fig. 2. Terminal lobe complexes can be observed at distal part of delta plain

3.3 Sedimentary architecture of autogenic process dominated delta

Combined with the sedimentary characteristics and evolution in different stages of the experiment, the sedimentary architectural model of autogenic process forced river-dominated delta in the three stages was established according to the observations made via the delta deposition process and quantitative analysis.

3.3.1 Sedimentary architecture in the initial stage

In the early stage, sedimentation was dominated by one or a limited number of feeder channels. Controlled by the feeder channel (s), three kinds of sedimentary architecture elements developed, including mouth bar, levee, and crevasse splay (Fig. 19a). Mouth bar was the main deposit and consumed the majority of the sediments during this stage. Its internal architecture was characterized by downstream accretions (Figs. 7 and 19a). Levees and small crevasse splays mainly formed at the end of this stage and were significantly thinner than mouth bars (Fig. 6). The feeder channel incised into the delta plain and was unfilled during the initial stage (Fig. 10).

3.3.2 Sedimentary architecture in the middle stage

Distributary splay and feeder channel filling were the main sedimentary architecture elements developed during the middle stage. Retrogradational bifurcation was the typical behavior of the feeder channel. Near-symmetric large distributary splay complexes developed on both sides of the feeder channel and the feeder channel was also filled with sediment (Figs. 14 and 19b). Due to the retrogradational bifurcation of the feeder channel, distributary splay complexes and channel filling was manifested as retrogradational patterns (Figs. 12 and 13). The continuous bifurcation of the feeder channel and the sediment deposition made the surface of the delta smoother, and the surface elevation gradually decreased from the feeder channel to both sides. Compared to the crevasse splays developing in the initial stage, the distributary splays developing during this stage were significantly larger and thicker (Fig. 19a, b).

3.3.3 Sedimentary architecture in the late stage

In this stage, the experimental delta was characterized by multi-branched radial distributary channels and terminal lobes. Originating from the source, these distributary channels were obviously smaller than the feeder channels developing in the former two stages (Fig. 11). These distributary channels often transport sediment to the area close to the shoreline and form terminal lobes (Fig. 19c). The lobes overlap each other, leading to a significantly smooth shoreline (Figs. 11c and 19c).

The main sedimentary architecture elements were terminal lobes that were deposited near the shoreline. For the most time of this stage, radial distributary channels just act as a shallow sediment transport pathway and thus hardly form channel filling deposits (Figs. 16 and 19). In addition, since the distributary channels were very shallow, overflow developed on both sides of the distributary channels. As a result, a small fraction of the sediments was deposited on the delta plain (Figs. 17 and 19).

4 Discussion: driven mechanism of the autogenic evolution in the experimental delta

The periodic evolution of the delta autogenic deposition process is completely spontaneous in the absence of external environmental forces like sediment supply, water flow, tectonic activity, etc. (Straub et al. 2015). Scholars have also discovered autogenic cycles in sedimentary systems such as meandering rivers (Miall et al. 2014), alluvial fans (Clarke et al. 2010), and deltas (de Haas et al. 2016; Trampush et al. 2017; Van Dijk et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2017). A similar experiment presented by Van Dijk et al. (2009) investigated the sedimentary process of a fan delta using non-cohesive sediment and a constant sea level. Cycles of alternating sheet and channelized flow demonstrated that the autogenic process was significantly periodic. In the natural environment, a large number of similar fan delta could be identified along the shoreline of basins in arid or semiarid climate (Van Dijk et al. 2009; Jia et al. 2016, 2018). In contrast, the river-dominated delta presented in this paper was simulated using cohesive sediment and constant relative base level. In modern environment and ancient stratigraphy records, this type of delta mainly deposits along the shoreline of basins in humid climate (Li et al. 2015; Ielpi et al. 2018).

Fine analysis of the periodic autogenic evolution process on the experimental delta shows that the main mechanism was the dynamic distribution of accommodation space in the sedimentary system and the following adaptive compensation of sediments (Trampush et al. 2017).

In the initial stage, with high elevation and flat topography, the delta plain has very limited accommodation space, while there is more accommodation space in the delta front (Fig. 20), which has two relevant effects on flows and sediments. One effect is delta plain erosion and the other is more sediment being carried into the delta front to form multi-period mouth bars (Paola et al. 2018). At the same time, the accommodation space on the delta plain gradually increased and even transformed from saturated into starvation (Clarke et al. 2010; Miall et al. 2014).

With gradual progradation of the mouth bars, the accommodation space in the area in front of the feeder channel mouth gradually reduced (Hajek and Straub 2017). Once the channel mouth area ran out of accommodation space, the feeder channel bifurcation formed a large-area distributary splay. Hydrodynamics of the bifurcated flow greatly reduced, leading to the rapid formation of the distributary splays. At this time, the accommodation space on the delta plain was significantly larger than that in the delta front. As the growing distributary splays continuously blocked the flows, bifurcation point was forced to retreat upstream. The delta plain was gradually filled from the mouth of the feeder channel to the source (Foreman and Straub 2017), eventually forming multi-period retrogradational and overlapping distributary splay complexes (Figs. 19 and 20). In the middle stage, few sediments were carried to the delta front, thus continuously increasing its accommodation space. As the consumption of accommodation space on the delta plain, the middle stage ended and the late stage began (Fig. 20).

In the late stage, because the accommodation space in the delta plain has been very limited, particularly the little space on both sides of the feeder channel, several smaller distributary channels radiating from the source point were formed (Fig. 20). These small distributary channels extended through a locally lower area to the delta front, and terminal lobes developed at the area close to the shoreline (Fig. 19). In general, in the late stage, the sediments mainly concentrated near the shoreline of the experimental delta (Clarke et al. 2010; Trampush et al. 2017). On one hand, the delta plain was dominated by aggradational deposits, and on the other hand, the delta front was dominated by progradational deposits.

Overall, the dynamic change of accommodation space between the delta plain and the delta front during the autogenic deposition process and the adaptive compensation of the sediments led to the migration of the sedimentary center in the delta (Fig. 20). Changes in the morphology, scale, and combined style of the sedimentary architecture elements ultimately led to complex configurations within the delta (Carlson et al. 2018; Foreman and Straub 2017; Hamilton et al. 2013; Miall et al. 2014).

5 Conclusions

Controlled by only autogenic process, the river-dominated experimental delta experienced several autogenic cycles. Each autogenic cycle generally consisted of three stages: the initial progradational stage, the middle retrogradational stage, and the late aggradational–retrogradational stage.

In the initial stage, one channel developed from the source point to the delta front. Consequently, a large-scale mouth bar was formed at the end of the feeder channel. The feeder channel incised into the delta plain and remained unfilled until the end of this stage. Several small-scale crevasse splays and levees were deposited on both sides of the channel (s).

In the middle stage, the feeder channel was blocked by the mouth bar which grew out of water at the end of the initial stage and resulted in the bifurcation of the feeder channel and the development of large-scale distributary splays. Due to reactivated accommodation space, continuous feeder channel bifurcation and associated distributary splays gradually retreated toward a sediment feeder, and the feeder channel was filled with sediments.

In the late stage, the feeder channel branched into a number of small-scale, radial channels. Each of these distributary channels fed a terminal lobe in the area close to the shoreline. With rapid migration of the distributary channels, a set of distributary channel-terminal lobe complexes were formed and stacked together.

The distribution of accommodation space and deposition on the river-dominated delta were not balanced everywhere. Active deposition can usually control a fraction of the area. When deposition happens at this place, cumulation of the accommodation space happens in the remaining area. Allocation of the accommodation space and the following adaptive compensation of sediments were the main control factors driving the autogenic evolution of the delta.

References

Ahmed S, Bhattacharya JP, Garza DE, et al. Facies architecture and stratigraphic evolution of a river-dominated delta front, Turonian Ferron Sandstone, Utah, USA. J Sediment Res. 2014;84(2):97–121. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2014.6.

Beerbower JR. Cyclothems and cyclic depositional mechanisms in Alluvial plain sedimentation. Kansas Geol Surv Bull. 1964;169(1):31–42.

Carlson B, Piliouras A, Muto T, et al. Control of basin water depth on channel morphology and autogenic timescales in deltaic systems. J Sediment Res. 2018;88(9):1026–39. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2018.52.

Clarke L, Quine TA, Nicholas A. An experimental investigation of autogenic behaviour during alluvial fan evolution. Geomorphology. 2010;115(3–4):278–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.06.033.

Clarke LE. The use of live vegetation in geomorphological experiments: how to create optimal growing conditions. Earth Surf Proc Land. 2014;39(5):705–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3534.

Clarke LE. Experimental alluvial fans: advances in understanding of fan dynamics and processes. Geomorphology. 2015;244:135–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.04.013.

Crosato A, Mosselman E, Beidmariam Desta F, et al. Experimental and numerical evidence for intrinsic nonmigrating bars in alluvial channels. Water Resour Res. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009714.

Edmonds DA, Slingerland RL. Mechanics of river mouth bar formation: implications for the morphodynamics of delta distributary networks. J Geophys Res. Earth Surf. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jf000574.

Egozi R, Ashmore P. Experimental analysis of braided channel pattern response to increased discharge. J Geophys ResEarth Surf. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JF001099.

Esposito CR, Di Leonardo D, Harlan M, et al. Sediment storage partitioning in alluvial stratigraphy: the influence of discharge variability. J Sediment Res. 2018;88(6):717–26. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2018.36.

Foreman BZ, Straub KM. Autogenic geomorphic processes determine the resolution and fidelity of terrestrial paleoclimate records. Sci Adv. 2017;3(9):e1700683. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700683.

Ganti V, Chadwick AJ, Hassenruck-Gudipati HJ, et al. Experimental river delta size set by multiple floods and backwater hydrodynamics. Sci Adv. 2016;2(5):e1501768. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501768.

Gong C, Wang Y, Steel RJ, et al. Flow processes and sedimentation in unidirectionally migrating deep-water channels: from a three-dimensional seismic perspective. Sedimentology. 2016;63(3):645–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12233.

de Haas T, van den Berg W, Braat L, et al. Autogenic avulsion, channelization and backfilling dynamics of debris-flow fans. Sedimentology. 2016;63(6):1596–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12275.

Hajek EA, Straub KM. Autogenic sedimentation in clastic stratigraphy. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2017;45(1):681–709. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-063016-015935.

Hamilton PB, Strom K, Hoyal DCJD. Autogenic incision-backfilling cycles and lobe formation during the growth of alluvial fans with supercritical distributaries. Sedimentology. 2013;60(6):1498–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12046.

Ielpi A, Fralick P, Ventra D, et al. Fluvial floodplains prior to greening of the continents: stratigraphic record, geodynamic setting, and modern analogues. Sed Geol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2018.05.009.

Jia H, Ji H, Li X, Zhou H, Wang L, Gao Y. A retreating fan-delta system in the Northwestern Junggar Basin, northwestern China—characteristics, evolution and controlling factors. J Asian Earth Sci. 2016;123:162–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2016.04.004.

Jia H, Ji H, Wang L, et al. Controls of a Triassic fan-delta system, Junggar Basin, NW China. Geol J. 2018;10:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.3147.

Kim Y, Kim W, Cheong D, et al. Piping coarse-grained sediment to a deep water fan through a shelf-edge delta bypass channel: tank experiments: piping sediment to a deep water fan. J Geophys ResEarth Surf. 2013;118(4):2279–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JF002813.

Li J, Liu S, Zhang J, et al. Architecture and facies model in a non-marine to shallow-marine setting with continuous base-level rise: an example from the Cretaceous Denglouku Formation in the Changling Depression, Songliao Basin, China. Mar Pet Geol. 2015;68:381–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.09.002.

Li Q, Yu L, Straub KM. Storage thresholds for relative sea-level signals in the stratigraphic record. Geology. 2016;44(3):179–82. https://doi.org/10.1130/G37484.1.

Lin C, He M, Steel RJ, et al. Changes in inner- to outer-shelf delta architecture, oligocene to quaternary Pearl River shelf-margin prism, northern South China Sea. Mar Geol. 2018a;404:187–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2018.07.009.

Lin C, Liu S, Zhuang Q, et al. Sedimentation of Jurassic fan-delta wedges in the Xiahuayuan basin reflecting thrust-fault movements of the western Yanshan fold-and-thrust belt, China. Sediment Geol. 2018b;368:24–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2018.03.005.

Miall, A. Autogenic processes: avulsion and architecture. In: Fluvial depositional systems. Springer, Cham. 2014; pp. 69–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00666-6.

Nicholas AP, Clarke L, Quine TA. A numerical modelling and experimental study of flow width dynamics on alluvial fans. Earth Surf Proc Land. 2009;34(15):1985–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.1839.

Paola C, Ganti V, Mohrig D, Runkel AC, Straub KM. Time not our time: physical controls on the preservation and measurement of geologic time. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2018;46(1):409–38. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-082517-010129.

Paola C, Straub K, Mohrig D, Reinhardt L. The, “unreasonable effectiveness” of stratigraphic and geomorphic experiments. Earth Sci Rev. 2009;97(1–4):1–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2009.05.003.

Qi K, Zhao X-M, Liu L, Su Y-Q, Wang H, Tan C-P, et al. Hierarchy and subsurface correlation of muddy baffles in lacustrine delta fronts: a case study in the X Oilfield, Subei Basin, China. Pet Sci. 2018;15(3):451–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-018-0239-9.

Reitz MD, Jerolmack DJ. Experimental alluvial fan evolution: channel dynamics, slope controls, and shoreline growth: experimental alluvial fan evolution. J Geophys Res Earth Surf. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JF002261.

Straub KM, Li Q, Benson WM. Influence of sediment cohesion on deltaic shoreline dynamics and bulk sediment retention: a laboratory study: influence of sediment cohesion on deltas. Geophys Res Lett. 2015;42(22):9808–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL066131.

Trampush SM, Hajek EA, Straub KM, Chamberlin EP. Identifying autogenic sedimentation in fluvial-deltaic stratigraphy: evaluating the effect of outcrop-quality data on the compensation statistic: identifying autogenic sedimentation. J Geophys Res Earth Surf. 2017;122(1):91–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JF004067.

Van Dijk M, Postma G, Kleinhans MG. Autocyclic behaviour of fan deltas: an analogue experimental study. Sedimentology. 2009;56(5):1569–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.2008.01047.x.

van Dijk WM, Van de Lageweg WI, Kleinhans MG. Formation of a cohesive floodplain in a dynamic experimental meandering river. Earth Surface Processes and Landf. 2013;38(13):1550–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3400.Ventra.

Ventra D, Abels HA, Hilgen FJ, et al. Orbital-climate control of mass-flow sedimentation in a Miocene alluvial-fan succession (Teruel Basin, Spain). Geol Soc Lond. 2018;440(1):129–57. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP440.14.

Wang J, Jiang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Flume tank study of surface morphology and stratigraphy of a fan delta. Terra Nova. 2015;27(1):42–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ter.12131.

Wellner JS, Sarzalejo S, Lagoe M, et al. Late quaternary stratigraphic evolution of the west Louisiana/east Texas continental shelf. SEPM. 2004;79:217–35.

Wright LD. Sediment transport and deposition at river mouths: a synthesis. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1977;88(6):857–68. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1977)88%3C857:STADAR%3E2.0.CO;2.

Wu S, Ji Y, Yue D, et al. Discussion on hierarchical scheme of architectural units in clastic deposits. Geol J China Univ. 2013;19(1):12–22. https://doi.org/10.16108/j.issn1006-7493.2013.01.001(in Chinese).

Yu L, Li Q, Straub KM. Scaling the response of deltas to relative-sea-level cycles by autogenic space and time scales: a laboratory study. J Sediment Res. 2017;87(8):817–37. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2017.46.

Zhang X, Wang S, Wu X, et al. The development of a laterally confined laboratory fan delta under sediment supply reduction. Geomorphology. 2016;257:120–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.12.027.

Zhao X, Qi K, Liu L, et al. Development of a partially-avulsed submarine channel on the Niger Delta continental slope: architecture and controlling factors. Mar Pet Geol. 2018a;95:30–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.04.015.

Zhao X, Qi K, Liu L, Xie T, Li M, Hu G. Quantitative characterization and controlling factor analysis of the morphology of Bukuma-minor channel on southern Niger Delta slope. Interpretation. 2018b;6(2):SD57–69. https://doi.org/10.1190/INT-2017-0147.1.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express sincere gratitude to Professor Straub and Dr. Qi Li from Tulane University for their open experimental data and patiently providing suggestions to the users, which has greatly assisted our research. This study was supported by a National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41802123), a China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (No. 2018M630843) and an Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Exploration Technologies for Oil and Gas Resources (Yangtze University), Ministry of Education (No. K2017-31). We highly appreciate the anonymous reviewers for the constructive comments and suggestions, which helped us to improve the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by Jie Hao

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, WJ., Zhang, CM., Yin, TJ. et al. Sedimentary characteristics and internal architecture of a river-dominated delta controlled by autogenic process: implications from a flume tank experiment. Pet. Sci. 16, 1237–1254 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-019-00389-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-019-00389-x